The Spectacle of the Fair

“One of the most spectacular and interesting special events of the exposition period,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle, was the June celebration of the “Night in Hawaii” that the fair’s Hawaiian Commission staged on the Palace of Fine Arts’ lagoon. Socialite Marion Dowsett Worthington ruled as queen for the evening. The event featured five princesses representing the territory’s five major islands, men in native costume rowing outrigger canoes, fireworks, and musical accompaniment by the popular Philippine Constabulary Band.1 The colonial implications of this performance could not be missed. A white American socialite queen ruled the islands, bringing them civilization and progress. The princesses and canoeists evoked nostalgia for the supposed traditional Hawaiian past while implying that the presence of American culture would doom that Hawai‘i to fade away and remain simply as a tourist attraction.2 Territorial governor Lucius Pinkham’s speech earlier in the day spelled out the relationship between Hawai‘i and the United States even more clearly when he focused on the military significance of Hawai‘i to the safety of the Pacific coast. “It is not for Hawaii that this great military and naval outpost is being established,” he stated, but rather for the protection of “your Pacific Coast, your cities, your commerce, and the mighty material and political progress of the United States of America.”3 It would be difficult to find a more naked statement of U.S. intentions in the Pacific.

This performance contained complicated messages about race, gender, and U.S. expansionism. Although Hawai‘i’s queen for the day was unequivocally white, the princesses who accompanied her were of mixed race, and they and other young mixed-race Hawaiian men and women featured prominently in performances at the Hawaiian Building. Sometimes these young men and women appeared at celebrations and in newspaper reports dressed as modern American youth, and only their wearing leis identified their “Hawaiianness.” Many scholars argue that the role of the nonwhite “other” at fairs was to appear as a foil to the supposed superior white American.4 The Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) emphasized social Darwinist ideals and scientific approaches to society and marriage and glorified the white male.5 The PPIE brought eugenics to the public’s attention through the Race Betterment Booth and meetings and widely publicized these ideas through such events as Night in Hawaii. But the lived reality of the fair was much more complex, and the PPIE’s official messages were more complicated than social Darwinism suggests.

Night in Hawaii juxtaposed a white socialite and the native princesses in a predictable way. But young Hawaiian women wearing shirtwaists and leis did not fit into this dichotomy of allegedly primitive versus civilized ideals. Instead, as children of both white and nonwhite parents, they suggested the possibility for peaceful racial integration and intermarriage. Hawai‘i’s status as a newly acquired U.S. territory highlighted the nation’s expanded role as an imperial power, while the competing goals of haole (whites who lived in Hawai‘i) organizers, native Hawaiian performers, and U.S. businessmen represented the tensions contained in U.S. expansionism. San Francisco businessmen staged the exposition to boost their city’s economic prospects. Within the walls of the PPIE fair directors designed a world that conveyed a vision of California history, U.S. society, and the U.S. relationship to the Pacific and Latin America that posited a dichotomy between perceived primitive and civilized cultures and nations. Much of the artwork and exhibits reflected popular theories of social evolution and the dominance of white men while reinforcing eugenic ideas about social progress and racial purity. But the participation of the young Hawaiian women reveals that this official narrative contained contradictions and faced competition from the contributions of other fair exhibitors. These participants from around the United States and the world, from the PPIE Woman’s Board to the government of Argentina, had their own agendas and goals for the fair that together conveyed a complicated and sometimes competing set of narratives about the world to visitors.

The elaborately landscaped and brilliantly colored grounds of the PPIE impressed upon visitors the accomplishments of California, the United States, and mankind. The lush gardens and colorful buildings emphasized the state’s natural bounty and beauty and implied the success of American expansionism in bringing U.S. culture to this paradise of a state. Huge exhibit palaces awed visitors with the newest examples of technological, artistic, and social development. Etiquette maven Emily Post wrote one of the most evocative descriptions of the grounds, noting that “to visualize the . . . Exposition in a few sentences is impossible. . . . In the shade or fog, it was a city of baked earth color, oxidized with any quantity of terra cotta; in the sun it was deep cream glowing with light.” The fair was perhaps most impressive, she noted, at a distance, after coming down from the hills of the city, when “you saw a biscuit-colored city with terra-cotta roofs, green domes and blue. Beyond it the wide waters of a glorious bay, rimmed with far gray-green mountains . . . or perhaps you looked down upon it at night when the scintillating central point, the Tower of Jewels, looked like a diamond and turquoise wedding cake and behind it an aurora of prismatic-colored searchlights.”6

The exposition stretched across the southern shore of San Francisco Bay. Officials acquired the 635-acre site from the federal government and through lease and purchase from private owners.7 Close study of previous fairs convinced fair directors of the necessity of designing a compact site, so they laid out the central section of the fair on a “block” plan. Designers arranged the main palaces in four blocks joined by covered corridors. Extensively decorated outdoor courts accompanied the palaces, making the PPIE a uniquely outdoor event that was quite distinct from previous American fairs. This central area contained the eleven main exhibit palaces and the Festival Hall. Farther west lay first the buildings of the states and foreign nations and, farther on, stood the livestock exhibit buildings, racetrack, aviation field, and drill grounds. The Joy Zone, or amusement section, covered 70 acres to the east of the central section.8

Rather than replicate the Beaux Arts “white city” of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, PPIE designers chose colors that reflected the California landscape and visually linked the fair to its western location. Directors appointed muralist Jules Guerin the first ever official “colorist” of an exposition, and he blended a palette of Mediterranean colors into the buildings across the fair, using “terra-cotta, ivory, cerulean blue, gold, green and rose.”9 Color even spilled onto the paths of the fair, where tinted red sand subtly accented the buildings’ colors.10 California writer Mary Austin noted Guerin’s success in echoing the colors of a California summer: “[The West] has made this exposition the richest dyed, the patterned splendor of all their acres of poppies, of lupines, of amber wheat, of rosy orchard, and of jade-tinted lake.”11 The abundant use of electric lights, particularly at night, emphasized the warm colors of the grounds. The beloved Tower of Jewels, a 435-foot tower covered with 125,000 reflecting “novagem” jewels of every color that sparkled in the sunlight, further accentuated the fair’s color scheme.

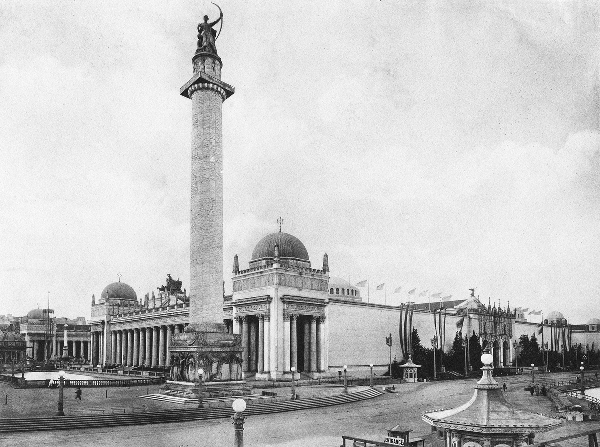

Fig. 6. Panoramic view of the exposition. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

Extensive greenery and flowers added bursts of color to the grounds. A living wall of shrubbery enclosed the site in part to shield visitors from the unpredictable bay winds and weather. This wall extended 1,150 feet along the southern boundary of the fair and reinforced the link between the fair and the California landscape. Within the grounds, as Portia Lee notes, vast flower beds and fountains further emphasized the “integration of the natural and built environment” and the “inherent, yet elaborated beauty of California nature.”12 The Court of Flowers alone featured fifty thousand yellow pansies and fifty thousand red anemones (replaced by begonias later in the season), borders of topiary mimosa trees, large lawns bordered by beds of creeping juniper, and boxed orange trees lining the paths.13

Fig. 7. South Gardens looking east and Tower of Jewels. (The Blue Book.)

The color scheme visually united the fairgrounds, but the architecture remained eclectic. Although dominated by classical styles, the courts and palaces defied easy classification. A visitor using the popular Scott Street entrance walked into the Court of Palms, a formal garden with lines of palm trees extending in both directions. To the left lay the Byzantine-inspired Palace of Horticulture, while on the right stood Festival Hall, which more closely resembled a Beaux Arts French theater. In front of the visitor stood the Tower of Jewels, which drew on Italian Renaissance themes.14 Beyond the Tower of Jewels lay the impressive Court of the Universe, modeled on St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and further incorporating Italian Renaissance styles.15 There East and West met, metaphorically represented in two statuary groups—Nations of the East and Nations of the West. Around the Court of the Universe stood four of the main exhibit palaces dedicated to agriculture, transportation, manufacturers, and liberal arts—each designed in its own unique combination of architectural styles. To the west of the Agricultural and Liberal Arts Palaces stood the Food Products Palace and the Education and Social Economy Palace. Across a small lagoon lay Bernard Maybeck’s famed Palace of Fine Arts and to the east of the Transportation and Manufactures Palaces stood the Mines and Metallurgy, Machinery, and Varied Industries Palaces. The architecture of the palaces may have been eclectic, but the color scheme and the compact court plan meant that visitors experienced a seamless transition from one part of the central fair to the other, walking in and out of impressively decorated courts and palaces.

In the eleven huge exhibit palaces, fair visitors could peruse seventy thousand separate exhibits along fifty miles of aisles. Exhibitors hoped their eye-catching displays would advertise goods to willing consumers and impress visitors with the progress and technological innovation evinced by American business, all while drumming up national and international customers. From the school-related displays in the Palace of Education and Social Economy to the pure food laboratory, the displays inundated visitors with information about new products, technologies, and processes. The Model T Fords that rolled off the assembly line in the Palace of Transportation signified for many the fair’s emphasis on technological progress. Visitors eagerly lined up at the Sperry Flour Company display in the Palace of Varied Industries to taste its famously delicious scones. A huge tower of Heinz 57 products impressed upon visitors the wonders of packaged foods and the variety of Heinz products as well.

Fig. 8. The Court of Palms, facade of the Palace of Liberal Arts (left) and the facade of the Palace of Education and Social Economy (right), PPIE, San Francisco. (Library of Congress.)

Fig. 9. The Court of the Universe. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

Fig. 10. One of many service and reform-minded exhibits that greeted visitors at the PPIE. (Library of Congress.)

Fair visitors thronged to the palaces to try out new gadgets and to learn about new inventions. Photographer Ansel Adams noted in his autobiography, “The intent of the Exposition was to encourage interest in and purchase of the items displayed. It was much more sensible than ordinary advertising: everything was there to see and handle and try out if you wished.”16 The new devices and electronics on display at the fair particularly appealed to young visitors. About the Eastman Kodak exhibit in the same building, thirteen-year old Doris Barr remarked, “They have some of the most beautiful Kodaks exhibited. . . . I wouldn’t mind having one at all!”17 Many visitors noted the fascinating new commodities they viewed at the fair. Numerous visitors praised the “House Electrical,” a full-size bungalow built right inside the Palace of Manufacturers. The small, California-style house featured all of the latest electrical appliances, from an electric dishwasher to a bottle warmer to an electric heater for a shaving mug.18 For visitors still amazed by the idea of an electrified house, the wonders contained therein must have been astonishing. Schoolteacher Annie Fader Haskell remarked that it “made one want to go housekeeping at once.”19

Moving west past the Horticulture Palace brought a visitor to the foreign buildings. Although some foreign nations failed to erect their planned buildings owing to the financial exigencies of war, many others put hundreds of thousands of dollars into staging impressive presences at the fair. Here, Japan, France, Siam, Panama, Persia, Honduras, Guatemala, Switzerland, Cuba, New Zealand, Denmark, Italy, Turkey, China, Argentina, the Netherlands, Bolivia, Sweden, Canada, and the Philippines all erected buildings. Inside, their commissions displayed historical relics and examples of traditional arts and crafts and showcased current agricultural and industrial products. North of the foreign pavilions stood the state buildings, where state commissions likewise featured examples of their own history and products. Still farther west lay the model marine camp, the livestock exhibits, the athletic stadium, and the polo fields.

Turning east out of the Scott Street entrance brought a visitor through the South Gardens and eventually to the Joy Zone, the amusement section named in honor of the Panama Canal Zone that featured the usual assortment of concessions. Visitors could tempt fate on roller coasters and thrill rides (one of which, the Bowls of Joy, resulted in multiple fatalities during the fair). Or they could watch dancing girls performing what contemporaries called “muscle dances.” Even more popular attractions included reenactments of key events in world history such as the biblical story of creation and the Dayton flood of 1913. Other displays, such as the enormously popular scale model of the Panama Canal and a display of premature infants in newly invented incubators, combined education and entertainment. Like all fairs of the era, the Zone also included the so-called ethnic villages, where groups of people envisioned as “others” by mainstream American society performed the tasks of their daily lives for observers.

Fair visitors faced myriad choices once they entered the PPIE’s gates. They could admire modern art either in the Palace of Fine Arts or along the avenues of the grounds, watch a theater performance, learn about educational reform in China or the Philippines, catch a glimpse of the salacious Stella (a painting of a nude woman that visitors swore breathed on its own) on the Zone, ride the Aeroscope for a stunning Bay Area view from high above the Zone, or learn more about the states and nations of the world in the buildings they designed and built. Many exhibitors featured “moving pictures” in their displays, and they became enough of a draw that after a few months, the official program issued each day of the fair included a lengthy list of times and locations where visitors could view the films.20 The fair offered visitors new experiences of all kinds—from art to food to amusement rides.

The outdoor nature of the fair offered an extensive canvas for works of art of all sorts. This art reinforced the fair’s larger messages about race, progress, and expansionism. PPIE head sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder noted, “It is the sculpture that interprets the meaning of the exposition, that symbolizes the spirit of conquest and adventure, and lends imagery to all the elements that have resulted in the union of the Eastern and Western seas.”21 Sculpture adorned every nook and cranny of the large palaces, courts, and towers. The San Francisco Chronicle proudly reported after opening day that the exposition “embodies completely the ultimate achievement of the race.”22 To PPIE officials, these achievements included U.S. domination of the American West, expansion in the Pacific, and the completion of the Panama Canal, which signaled the nation’s destiny “to dominate the politics and commerce of the Pacific.”23 They hoped that the exposition would provide the city with “world-wide power and fame and prominence” and assert San Francisco’s position as the preeminent city of the Pacific.24 Underlying those assertions was a belief in the inevitability of progress and of American expansionism, in the fact of both social and scientific evolution, and in the superiority of U.S. values and culture, all of which found expression in the public art of the fair.

Any visitor who somehow missed the fair’s rhetorical celebration of progress could find it visually inscribed in the fair’s courts and statuary, most prominently in the Column of Progress, and in the Court of the Ages (also called the Court of Abundance). The 185-foot-high Column of Progress dominated the fair’s South Gardens and caught the attention of all who entered. According to Calder, the statue celebrated “the unconquerable impulse that forever impels man to strive onward.”25 Atop the statue stood the Adventurous Bowman, a partially nude man shooting an arrow into the sky while surrounded by a “circle of toilers” and a patiently attentive woman. A series of relief sculptures symbolizing the “labors and aspirations of men” circled the base of the column.26 While the column encapsulated the entire narrative of the fair in its story of man’s social advancement and achievement, the Court of Ages depicted the process of biological evolution and progress. Designed by architect Louis C. Mullgardt, the court featured the 219-foot-high Tower of Ages, whose successive altars depicted the ascent of man from “primitive savage to the regnant modern spirit.”27 The arcades housed the oft-praised murals of Frank Brangwyn that depicted in bold color men’s engagement with the elements: air, earth, fire, and water. Figures of primitive men and women engaged in the toil of everyday life appeared around the base of the tower. Images of less evolved life forms, such as crabs and fish, along the tower’s lower edge further emphasized the ideas of evolution. Four statuary groups of human figures stood within the central fountain. Their titles included Natural Selection and Survival of the Fittest, further encapsulating the theme of life as men’s struggle with each other for success and dominance.28 Both scientific and social Darwinism claimed a prominent place in the art of the fair.

Artwork depicting U.S. territorial expansion appeared at the fair to prove the inevitability of human progress. Murals and sculptures across the grounds glorified the energetic, virile western spirit. Across from the Column of Progress stood the Fountain of Energy, which featured a young, athletic man riding a “fiery horse, tearing across the globe.”29 The fountain was, in Calder’s words, “a joyous aquatic triumph celebrating the completion of the Panama Canal.”30 Another critic described it as “a symbol of the vigor and daring of our mighty nation, which carried to a successful ending a gigantic task abandoned by another great republic.”31 While this fountain and the Column of Progress immortalized American achievements, other pieces offered a western inflection of the national narrative, with statues commemorating the Spanish conquest of the Americas and California. Statues of both Francisco Pizarro and Hernán Cortés stood in front of the Tower of Jewels, while figures of a padre and a pioneer appeared in its niches. Two fountains designed by female artists—El Dorado (Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney), which celebrated the discovery of gold in California, and Youth (Edith Woodman Burroughs)—reminded viewers of the restless California spirit. Beneath the Tower of Jewels, visitors could admire murals depicting the history of the Panama Canal in visual form, from Balboa’s encounter with the Pacific to the canal’s triumphant completion by Americans. The richly colored grounds, abundant flowering bushes and trees, and eclectic architecture further accentuated the active, vibrant western nature of the fair. It represented a West and a California settled by white men who triumphed over nature and savagery and who remained full of energy for the challenges to come.32

Fig. 11. Palace of Agriculture and Column of Progress. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

Two of the fair’s most popular statues accentuated this celebration of expansionism. The End of the Trail and The American Pioneer each provided important visual symbols to Californians intent on writing their own history. The End of the Trail went on to become an icon, but its pairing at the PPIE with The American Pioneer emphasized the racial overtones of the statue.33 James Earle Fraser’s The End of the Trail depicted an Indian man slumped forward on the back of an exhausted pony. According to the exposition’s Blue Book, “The drooping storm-beaten figure of the Indian on the spent pony symbolizes the end of the race which was once a mighty people.”34 Solon Borglum’s The American Pioneer showed an old frontiersman wielding an ax and rifle on the back of a prancing horse. The Blue Book informed readers that the man “muse[d] on past days of hardship, when these implements and the log hut and stockade dimly indicated on the buffalo robe which forms his saddle housing, were his aids in subjugation of the wilderness.”35

Fig. 12. The End of the Trail by James Earle Fraser. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

Fig. 13. The American Pioneer by Solon Borglum. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Together these statues celebrated the ascendance of Anglo men in California and evoked the power of the pioneer myth in San Francisco. While Fraser’s Indian leaned over his pony, defeated, utterly fatigued, and held his spear pointed down toward the earth, the pioneer, although past his glory days, was still able to look back at his weapons and wield them with youthful vigor. These two statues fit logically into a historical narrative of the West that was influenced by social Darwinism and contemporary rhetoric about the “vanishing Indian.” The frontier was closed—both the census of 1890 and historian Frederick Jackson Turner had made that clear—so the days of both the Indian and the pioneer were finished. Yet as the pioneer had succeeded in his mission, he was able to reminisce in peace while the Indian fought to stay astride his tired steed.

A children’s book published in 1915 chronicling one family’s visit to the fair reveals the power of the two statues to convey their message about race and progress: “We saw just how tired both man and horse were and felt sorry for them. We asked Father why they had come so far to get themselves exhausted like that, and he again told us something of symbolism. The statue is intended to represent the redman, and denotes that the race is vanishing, and is supposed to be studied in connection with the ‘Pioneer.’ . . . That is meant to say that the white race will take up the work of progress and carry it on.”36

It is no surprise that fair directors welcomed The American Pioneer to the fairgrounds since San Franciscans still clung to the image of the pioneer as their link to their Gold Rush past and the city’s founding.37 The Gold Rush played the primary role in the narrative of the city’s development. City residents embraced memories of the rough and tumble Gold Rush days, when prospectors set out for the gold fields from the city and clever merchants set up shop to outfit miners and made large fortunes in the business. These statues reemphasized the deep connections between the city of San Francisco and the racialized mythology of the exposition.

Nowhere were the mythic pioneer and his companions more heartily celebrated than in the Court of the Universe. There, two huge sculptural groups, Nations of the East and Nations of the West, visually represented the fair’s joining of the East and West. Both groups contained stereotypical representations of their subjects, particularly of women, but closer examination reveals they were more nuanced than they first appeared. The Nations of the East depicted an “Indian prince on the ornamented seat and the Spirit of the East in the howdah, of his elephant, an Arab sheik on his Arabian horse, a negro slave bearing fruit on his head, an Egyptian on a camel carrying a Mohammedan standard, an Arab falconer with a bird, a Buddhist priest, or Lama, from Thibet, bearing his symbol of authority, a Mohammedan with his crescent, a second negro slave and a Mongolian on horseback.”38 As one art critic noted, this composition “breathed the spirit of Oriental life wherever found.”39 The Nations of the West comprised a French-Canadian trapper, an Alaskan woman, a Latin American, a German and an Italian on either side of a pair of oxen, an Anglo on horseback, an “American squaw” with a papoose, and an Indian man on horseback. Mother of Tomorrow, depicting a pioneer woman leading a prairie schooner, appeared at the center of the group. The Heroes of Tomorrow, featuring two young boys, one white and one black, stood above her and beneath the crowning depiction of the spirit of Enterprise. Given that the two groups literally towered above the heads of exposition goers, it is difficult to know what fairgoers made of them or how closely they were able to examine the finely detailed figures. Did they perceive the Nations of the East as examples of “exotic but primitive peoples,” as Elizabeth Armstrong has claimed, or did they simply admire them as one more Asian element of this Pacific exposition?40

The Nations of the West offered a more complicated picture of westward expansion than did The End of the Trail or The American Pioneer. One official guidebook told visitors that the group was designed to depict the “types of those colonizing nations that have at one time or place or other left their stamp on our country.”41 The three native figures—one Alaskan and two Indians—were portrayed as weighed down with labor and care, but their very presence in the composition wrote them into the story of the West and acknowledged their contributions to American life. The Mother of Tomorrow limited women to a reproductive role, but it acknowledged women’s place in the move west and expanded the story beyond the solitary male pioneer. The most interesting figures, however, were the Heroes of Tomorrow. Here, Calder chose to depict a white child and a black child holding hands and to label them both “heroes,” suggesting they represented hope for the future. Was this piece an interracial vision of harmony? At least one African American contemporary writer chose to interpret them this way. Freeman Henry Murray Morris argued that the Heroes of Tomorrow, which was also called Hopes of the Future, represented a hopeful vision of racial harmony. He went on to argue that the two “Negro servitors” in the Nations of the East were no more servants than were the German and Italian figures “attendants” to the oxen. Whether viewers shared this view is unknown, but Morris’s argument makes clear both the malleability of the interpretation of these artworks and the progressive nature of Calder’s artistic vision.42

Fig. 14. Nations of the East. (Souvenir Views of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. San Francisco, 1915.)

Fig. 15. Nations of the West. (Souvenir Views of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. San Francisco, 1915.)

The Mother of Tomorrow found a compatriot on the grounds thanks to the PPIE Woman’s Board, whose widely praised Pioneer Mother statue commemorated the female role in westward expansion. The debates surrounding this statue reveal the presence of a gendered agenda on the fairgrounds and offer a glimpse into the polarizing nature of the fair. The statue also demonstrates the ways in which the fair offered multiple official messages about U.S. society and the world. The Woman’s Board deliberately inserted itself into the fair’s official narrative by erecting a statue that filled a perceived void in the fair’s official historical narrative.

In 1913 Ella Sterling Mighels suggested the idea for a tribute to the pioneer mother, and to mothers in general, to John E. D. Trask, director of the PPIE Department of Fine Arts. Mighels, a conservative proponent of what scholars have termed “maternalism,” had long worked for an appropriate memorial to the work of pioneer mothers. Brenda Frink argues that Mighels was motivated by a desire to “promote white women’s traditional moral influence over middle-class men, to argue against both labor unrest and Asian immigration, and to inculcate old-fashioned pioneer morality among urban children.”43 Mighels’s goals were soon subsumed by those of the PPIE Woman’s Board, to whom Trask brought the idea. The board found the idea “irresistible,” despite worries about raising funds in a state already beset with pleas from the PPIE for support. The board quickly organized the Pioneer Mother Monument Association to solicit donations from women across the state.44

The association promised that the monument would commemorate “the Pioneer Mothers of the West—the self-sacrificing women, with their little ones at their side, who braved the dangers and underwent the hardships and privations . . . [of] pioneer life.”45 Supporter Anna Morrison Reed, a newspaper editor in Ukiah, California, reminded readers that these women “gave, during the hardships of the early days, the comfort and the refining touch to their rough surroundings, and turned the camps of men into the homes of the early Pioneers. . . . Many died along the way, . . . martyrs to their duty to their families.”46 This emphasis on the noble sacrifice of pioneer mothers permeated the campaign.

The goal of the Woman’s Board of constructing its own vision of California history struck a chord with fellow Californians. Pioneer heritage groups and individual donors contributed extensively.47 Governor Hiram Johnson even declared October 24, 1914, “Mother Monument Day” in an effort to raise funds. Striking support came from schoolchildren. Because “there was a sincere desire [on the part of organizers] that the monument should represent the little given by many so that its significance should not be lost,” President of the Woman’s Board Helen Sanborn arranged with the state schools’ superintendent to involve children in the fund-raising effort. Children contributed their pennies to a total of $1,362.02, an amount estimated to represent 136,000 children.48

A conflict soon arose between the board and sculptor Charles Grafly that revealed the class and race assumptions underlying the monument effort. Grafly’s original design featured a woman wearing buckskins, sheltering two nude children. Mighels hated the statue, as did the editor of the San Francisco Call, who noted the pioneer mother must be “a figure of strength, of dignity, but worn by hardship and courage, and with that fine beauty which comes with self-sacrifice, devotion, maternity and love.”49 A primitive mother who wore skins evoked the ideal of primitive womanhood against which these white women were actively constructing themselves and not the vision of “American womanhood” that they wished to convey. Mighels rallied the women of the Native Daughters of the Golden West to protest Grafly’s design, and the Woman’s Board summoned him to San Francisco. The conflict continued after he refused to clothe the children. The Woman’s Board and Grafly volleyed back and forth over the issue until they reached a solution that left the children unclad but slightly less visible in the composition.50 Woman’s Board historian Anna Pratt Simpson noted that the solution was solved once Grafly realized “the original idea of the universal mother.”51 Apparently, the women of the board were able to tolerate nude children as long as their mother appeared to be a white, middle-class American rather than a skin-clad primitive woman of indeterminate race and class status.

Fig. 16. Pioneer Mother. (Souvenir Views of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. San Francisco, 1915.)

The finished statue depicts a mother with two small children in front of her. The mother wears a small sunbonnet, a homespun dress, and a short cape around her shoulders. Arms outstretched, she holds the hand of her small daughter. The son echoes his mother’s gesture, wrapping his other arm around his sister. Both children are nude and appear to be walking forward with their mother, whose rough boot peeks out from beneath her skirt. The woman memorialized in this statue is clearly marked as white rather than as native or Californio. By defining her as the Pioneer Mother the Woman’s Board erased the experiences of the many other women who lived in California at the same time. By calling for a monument of a white pioneer mother to stand for “Motherhood, the Womanhood of the nation,” the Woman’s Board asserted in strong terms the link between white women, civilization, and nation building. The pioneer mother was the mother of the nation, according to this formulation, a position that vested in white, middle-class women the power to turn a rough men’s camp into a home and a state, ready for inclusion in the national polity. White, middle-class mothers became absolutely essential to the creation of civilization.

The Pioneer Mother stood in a prominent location near the Palace of Fine Arts. It stimulated a great deal of local interest and debate, suggesting the power of the image for many Californians. Some, like Mighels, continued to oppose the final version, preferring instead a romanticized, sentimentalized portrait of a refined, middle-class matron rather than the more realistic image of a woman in homespun and half-soled shoes. Such an image suggested the primitive rather than the civilized, and boosters of the statue did not want to imagine their mothers or grandmothers as primitive. Frink also suggests that the statue’s secularism and nudity fell far short of Mighels’s vision of women as a moralizing and Christianizing force.52

Other fairgoers commented positively on Pioneer Mother, confirming that the Woman’s Board’s efforts to centralize motherhood within their vision of womanhood and California history had struck a nerve. Laura Ingalls Wilder, later the famed children’s author of the Little House on the Prairie books, spent the summer with her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, in San Francisco and wrote home to her husband about Pioneer Mother, noting, “It is wonderful and so true in detail.”53 Through the campaign for Pioneer Mother, the members of the Woman’s Board staked out a space—one that was visual, three-dimensional, and rhetorical—for a vision of white womanhood in which women were absolutely essential to westward expansion. In a fair that celebrated the conquest of California and America’s position as an imperial power, this claim was a powerful one.

Visitors to the fair encountered another visual link between whiteness, womanhood, and California history in the official California State Building, which the PPIE Woman’s Board ran. Architects designed it in the style of the California missions, complete with a reproduction of the Santa Barbara Mission’s “Forbidden Garden.”54 There, the group of elite Bay Area women held dansants (afternoon dances) for invited guests and hosted dinners and receptions for visiting dignitaries from around the nation and the world. Their position in the California Building complemented the message of the Pioneer Mother. The design’s visual link to the white (in this case Spanish) conquest of California affirmed the board members’ relative position to the nonwhite peoples of the fair. As the official protectors and hostesses of women on the grounds, the members of the Woman’s Board appeared at the fair as models of propriety and decorum, with their staid portraits often reproduced in fair publicity.55

The PPIE Woman’s Board officially worked to improve the reputation of both California and San Francisco rather than address issues of women’s status or rights. These actions somewhat aligned their mission with that of the exposition board. Simpson’s history of the Woman’s Board noted that the “Board . . . saw that, unlike other expositions, the one to be held in San Francisco vivified a great issue and was not commemorative of century-old happenings, and that it would mean responsibilities in the years to come that should be borne in part by the women, if the State received the greatest possible benefit.” These responsibilities included readying the state for the “tide of immigration” expected after the opening of the canal and addressing “the serious problems [that] could arise with greatly increased travel”—that is, undertaking extensive protective measures for young people and those traveling alone.56 The board perceived helping immigrants and protecting young people as integrally connected. If the fair and the city appeared to be morally suspect and dangerous to travelers, then settlers would be wary of making the long journey to California. Where the women of the board differed from their male counterparts was in their belief that moral protective work was essential to furthering the reputation of their city and state. They worked to bring attention to specific issues that threatened the success of the exposition.

The board involved women throughout the state in their efforts by creating a State Auxiliary, which raised funds for the fair and advertised the bounty and beauty of California to visitors. County groups, which swelled to a membership of more than fifteen thousand by 1915, publicized the fair in their home counties and kept the California Building running smoothly throughout the fair. Their role, however, was far more than simply that of raising funds. According to an early outline of the plan for county auxiliaries, the local groups would be responsible not only for supporting efforts surrounding the fair but also in preparing their home counties for the “visitors and prospective settlers who will be looking over the state with a view to securing congenial homes and profitable locations.” Women serving as county chairmen were also charged with finding capable women who could serve on juries for determining fair awards and with cooperating with local county exposition commissioners, chambers of commerce, and county supervisors in order to “exploit [sic] . . . their county resources and to further the work of adequate display at the exposition.”57

Fig. 17. Mrs. Phoebe Hearst speaking at the ground-breaking for the California Building, May 7, 1914. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Celebrating the success of the white pioneer and his helpmate, the pioneer mother, and emphasizing the bounty and fertility of California’s countryside fit into boosters’ plans for the PPIE. Publicists created idealized visions of both California and San Francisco to draw businesses, tourists, and settlers to the state. The opening of the Panama Canal would make it easier for European immigrants to reach California, so publicists emphasized the state’s ties to Europe. Despite the fair’s Pacific theme, fair publicists were careful not to imply that California was a part of this nonwhite Pacific world. San Francisco offered businessmen both a taste of the goods of Asia and an entrée to Asian markets, but the city and state itself, the PPIE proclaimed, were safely “white.” Publicity linked California to Europe, not Asia, and envisioned a state populated with Europeans rather than Asians, Latin Americans, or native peoples. As one pamphlet described “California the Hostess”: “Take the sunniest parts of sunny Italy and Spain and the South of France with their wealth of vineyards and orchards; . . . place here and there the more beautiful bits of the French and Italian Rivieras with their wooded slopes and silvery beaches, joyous crowds, and gay life; bound this collection on one side by the earth’s longest mountain range and on the other by the largest ocean, and cover with a canopy of turquoise blue sky and brilliant sunshine and you have a picture that yet falls short of—CALIFORNIA THE GOLDEN.”58 Comparing California to the nations of western Europe continued the fair’s privileging of European culture and defined a host of other peoples as outside the bounds of the white race.59 Emphasizing California’s similarity to Europe reassured potential visitors who feared the state was simply too far away—or too full of Asians and other nonwhites—to be “civilized.”60

Celebrations of California communities held during the fair visually and rhetorically linked whiteness, gender, and California society for visitors. During each county’s “special day” at the fair, representatives showed off their home counties’ unique products and features in an extended advertisement for the bounty and beauty of the state. Most, if not all, of these celebrations (as well as the celebrations of other states and cities) included the participation of young, attractive white women who showed off the produce of the county in question. Local newspapers prominently displayed pictures of these women alongside reports on the events. The San Francisco Chronicle’s report on Orange County Day described the “orange girls wearing orange ribbons in their hair and tossing oranges by the armful to the crowd.” Alongside the story appeared the picture of “Miss Freda Sander, one of the pretty orange girls distributing oranges from Orange County yesterday at the exposition.” Her face and upper body appeared superimposed on a gigantic orange, as if to emphasize the link between oranges and youthful beauty.61 These women represented California’s fecundity, and their beauty advertised the state’s natural bounty and plenty. Using young white women to represent the state’s fertility served as one way to reassure potential settlers that the future of the state lay with its white inhabitants.

The PPIE’S narrative of the American conquest of the West led seamlessly into a celebration of the opportunities the Panama Canal would bring to California and the nation. Late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century advocates of American imperialism believed that American westward expansion laid the groundwork for U.S. expansion abroad. The fair highlighted California’s connections to both Latin America and the Pacific, reflecting the nation’s growing role on the world stage and its political and economic interests abroad. The 1904 Roosevelt Corollary justified U.S. involvement in Latin America, and in 1915, U.S. troops occupied the nation of Haiti in one of the many resulting military interventions. Meanwhile, makers of foreign policy closely watched the ongoing Mexican Revolution, where the United States had intervened the year before by occupying the port of Veracruz. In the Pacific, the question of Philippine independence continued to fester, as Filipinos demanded it and U.S. lawmakers discussed its possibility in Congress. The 1911–12 Chinese Revolution had offered American missionaries and businessmen new opportunities to push for American influence in Asia. The PPIE explicitly highlighted U.S. involvement in the Pacific and Caribbean by emphasizing the economic possibilities that the completion of the Panama Canal offered and by glorifying the virility of the pioneer male who had conquered California and the West.

To make these claims real, fair directors introduced visitors to a Pacific and Latin American world intertwined with U.S. interests. First, they solicited the involvement of foreign nations. The federal government appointed official commissions to travel to Europe, Asia, and Latin America and to make official diplomatic overtures to the governments of as many nations as possible. PPIE officials used informal forms of diplomacy as well, drawing on information and support from U.S. businessmen and foreign residents of the Bay Area. When visiting commissioners came to San Francisco, the PPIE spared no expense on wining and dining them in an attempt to convince them to commit to participating in the fair. Although the war in Europe prevented the participation of many European nations, a substantial number of nations and colonies from the rest of the world showed up in San Francisco. From the Pacific Rim, Japan, China, Siam, Australia, the Philippines, Hawai‘i, and New Zealand sent official commissions, and amusement attractions featuring Hawaiians, Maoris, and Samoans greeted fair visitors. Latin American nations, including Argentina, Cuba, Honduras, Guatemala, and Bolivia, also participated.

Boosters believed that the opening of the Panama Canal would stimulate trade with both Asia and the Americas. Pre-fair discussions and publicity emphasized the opening of Asian markets. Boosters also sang the praises of increased hemispheric cooperation. When the California Development Board and the PPIE directors feted U.S. secretary of state Philander Knox at a 1912 dinner, he told San Franciscans of the benefits of “opening the Isthmian golden gate for the material and profitable interchange of all the communities of the three Americas.”62 Moreover, he assured them, “the function of the canal in promoting the good mutual relations of different communities is hardly to be exaggerated.”63 Such rhetoric permeated internal exposition reports about the nations of the Americas. The official South American PPIE Commission noted upon its return, “The opportunities for investors and colonists [in Latin America] are numerous . . . the colonist or investor who has a knowledge of his requirements can be suited in the various countries of South America.”64 Canal and fair boosters promised that huge swaths of Latin America would now be more easily accessible for both Americans and Europeans and that San Franciscans and Californians need only seize the moment to profit.65 Local residents similarly hoped for an increase in economic and social exchanges between Latin America and San Francisco. In 1914, Oscar Galeno and J. J. Martin launched a new biweekly newspaper, Las Americas, in San Francisco with the goal of reporting on the “commercial and social relations” within the Americas and with the Philippines, which they perceived as essential to the economic future of the United States.66

Scholars have largely ignored the Pan-American nature of the PPIE since San Diego’s Panama-California Exposition more strongly emphasized the state’s ties to Latin America. Nonetheless, other American nations staged impressive presences at the fair, and ideas of Pan-Americanism and hemispheric unity lurked beneath the surface of the fair. Robert Gonzalez details the elements of Pan-Americanism, or “hemispherism,” as it emerged at earlier fairs: “Hemisphericism was denoted in three ways: through the selective participation of nations; through the careful selection of the contents displayed at each fair; and with the invocation of hemispheric themes of a common Pan-American heritage explored in the fairs’ architecture, propaganda, and events.”67 Although the hemispherism of the PPIE was more limited than that of the 1901 Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York, for instance, the active interest and participation of Latin American nations in the PPIE and the emphasis on a shared Spanish past made the fair a Pan-American event.

For those already interested in Pan-American affairs, the PPIE offered a significant opportunity to strengthen ties among the nations of the Western Hemisphere. The visits of Latin American dignitaries to San Francisco allowed for informal strengthening of diplomatic relations between the United States and various nations. When Brazilian foreign minister Lauro Müller toured the United States in 1913, John Barrett, the head of the Pan American Union, reminded fair officials that his stop in San Francisco would be “one of the most important events in the history of Pan American relations.”68 Brazil failed to erect a building at the fair because of financial exigencies after the outbreak of war, but in the pre-fair years its representatives received much attention from fair officials. When Latin American officials spoke publicly on these visits, they usually emphasized their desire for progress, in keeping with the fair’s themes of progress and civilization. A Dominican representative noted at his nation’s site dedication that he and his nation hoped “we may not be left behind in that westward race by which Civilization, arrayed with Steam and Electricity, and with Law and Justice, goes on and on, opening seas, laying out rails, immersing cables, . . . cleaving continents, in order that all shadows shall disappear.”69

The PPIE occurred at a time when the relationship between the United States and Latin America was in flux. Barrett and many Latin Americans were pushing for a multilateral relationship between the United States and Latin America that would downplay the Monroe Doctrine and create an equal political relationship among all of the nations of the region.70 The official rhetoric of the PPIE, however, reiterated the relationship first set out in 1823 in the Monroe Doctrine and more recently reaffirmed in the Roosevelt Corollary. Upon the dedication of the Honduras Building, for instance, Michael H. de Young presented an honorary bronze plaque to the Honduras Commission, noting, “We, as the big brother—the great republic—look on every republic on this hemisphere as part of us, and we congratulate ourselves that the power and strength of the people has risen in every section of our hemisphere until all are republics.”71 Some canny Latin American representatives echoed these sentiments, praising the U.S. role in the region. On Cuba’s dedication day Gen. Enrico Loynaz del Castillo, a hero of the Cuban war for independence, praised the role the United States had played on the island, noting that “a government, powerful like this of yours . . . must be forever the guardian of Cuban emancipation.”72 Such sentiments are hardly surprising given the context. The exposition was held in the United States, and it was pro forma for visiting dignitaries to praise the host nation. Moreover, the celebration of the Panama Canal necessitated recognition of the U.S. role in the region, and any respectable diplomat would make the correct statements about his nation’s gratitude for this momentous achievement.

These public statements by both U.S. and Latin American officials suggest that the fair presented a portrait of U.S.–Latin American relations that echoed the U.S. government’s official diplomatic position on Latin America. The United States was the protector of the region and would act as a policeman when necessary. The fair’s focus on the economic possibilities that the canal offered added further nuance to this vision, as both Latin American and U.S. representatives stressed the enormous economic opportunities that Latin American nations presented. Other commentators emphasized the opportunity that the Panama Canal would afford for immigration, not only to the U.S. Pacific coast, but also to the nations of Latin America. Barrett noted in a 1915 publication promoting the fair that the canal would allow much easier access to the Pacific coast of Latin America, where he hoped both Europeans and Americans would settle after the war.73

But the nations of Latin America had their own goals for the fair, and they did not always mesh with those of the United States. Every nation emphasized their economic possibilities. Honduras and Guatemala, for instance, each displayed their many natural resources—coffee, sugar, bananas, tobacco, coffee, and so on—as well as their recent history of “ordered, progressive government.”74 Political and economic instability in many nineteenth-century Latin American nations had made it difficult for them to gain foreign investors. As the region entered the twentieth century and political conflicts between Liberals and Conservatives lessened and presidents held office for somewhat longer terms, they began to look north and east for investors. Participation in the PPIE was a part of their strategy to attract foreign investment and to stimulate their economies, and painting a picture of their nations as politically stable and rich with natural resources helped them achieve that goal.

Fig. 18. The Argentine exhibit in the Palace of Education and Social Economy was among many foreign exhibits designed to show off the progress of the exhibiting nations. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Although these nations presented themselves within a framework that envisioned them as junior partners to the United States, chinks in that picture emerged. Argentina built one of the most impressive palaces at the fair and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars presenting itself as a progressive, modern nation. Frank Morton Todd, official fair historian, noted, “The lesson was borne in upon the beholder that he would have to throw away the old teachings . . . and instead of thinking of Argentina as a land of vast undeveloped natural resources, begin to think of it as a country with her feet set upon the highway of the world’s best progress; her capital . . . the abode of wealth and culture . . . her government scientifically administrated.”75 Another visitor noted that the building had a “fine library . . . and much information regarding commerce of the country, showing it to be most progressive.”76

Fair visitors who picked up the official souvenir books available at the Argentina Building received concrete examples of Argentina’s modernity and progress. The pamphlet began by likening Argentina to the United States, with similar histories of conquest and warfare leading to a liberal and just state. But the author soon offered substantive critiques of U.S. policy.77 In Argentina, for instance, no immigrant faced limitations on property ownership or employment opportunities. Overall, Argentina had “fewer limitations” on foreign residents than the United States did, the author noted, suggesting a clear comparison to the latter’s discriminatory policy toward Asian immigrants.78 Since Argentina’s neighbor Brazil began actively recruiting Japanese immigrants in 1908, after the United States had banned the entry of Japanese laborers, Argentina may also have been attempting to recruit Asian immigrants. An exhibit in the building about the “Immigrant Hotel” in which immigrants were housed while waiting processing also emphasized the nation’s welcoming attitude toward all immigrants, one that stood in direct contrast to the increasing anti-immigrant agitation brewing in the United States.79

The pamphlet also emphasized Argentina’s growing international political power. One of the nation’s recent achievements, the author related, was the adoption of a new international agreement regarding the collection of national debts owed to foreigners. Long an issue between Latin American governments and the European powers, the 1902 doctrine adopted at The Hague in 1907 stated that foreign powers could no longer use armed forces (usually warships) to gain repayment of debts. The choice to discuss this issue in the souvenir publication indicates Argentina’s desire to be seen as a world power able to make its own diplomatic decisions and policy.80 The publication’s author offered even stronger criticism of U.S. economic policies in its discussion of Argentina’s enormous economic potential. High tariffs and insufficient steamship lines badly hindered U.S. trade with Argentina, suggested the author. Now, however, the time had come to make Argentina’s commercial relations with the United States “more reciprocal.”81

In the foreign pavilions, visitors encountered visions of nations carefully crafted by their commissions and not by fair officials. From Cuba to Honduras to Argentina, visitors saw both examples of the rich and varied natural resources of the Americas and concrete evidence of each nation’s moves toward modernity and progress as defined by the Western powers. Cuba’s building emphasized, not surprisingly, links between the United States and Cuba and the favorable influence of the U.S. occupation on the island’s progress, particularly in terms of education. As one visitor remembered, the building “made much of public schools showing increase in attendance.”82 Guatemala and Honduras emphasized their political stability and developing education systems, as well as the many opportunities awaiting investors and immigrants.

The displays of territories tied to the United States wholeheartedly celebrated U.S. expansionism and asserted San Francisco as an entrée to that world. The Philippines Building featured examples of the U.S.-implemented education system on the islands and of the progress made under U.S. rule. One guide noted, “The progress of the inhabitants since their [Philippines] acquisition by our government is one of the most interesting studies in this building.”83 Young Doris Barr pasted into her diary an excerpt from a guidebook that described the Philippine portion of the U.S. government’s exhibit in the Palace of Liberal Arts. The display showed a group of people, presumably a family, inside a hut and wearing loincloths and skins. One young boy holds a parrot in his hand while his father wields what appears to be a spear. The overall impression was one of stereotypical “primitiveness.” The caption reads: “Here are shown, in excellently made lifelike figures, some of our wards in the Philippine Islands. These are some of the people for whom self-government is proposed.”84

Some exhibits juxtaposed the “primitive” with the “civilized” in an effort to demonstrate progress to viewers. Laura Foote Bruml’s record of her visit to the Philippines Building noted the many improvements made to the islands since the Americans took possession of them. Juxtaposed with these “improvements in roadways, bridges, buildings, and locomotion” were “horrid knives, swords, cleavers, etc., which had seen use by wild tribes.” Finally, she praised the “intelligent Phillipino [sic] exhibitors who say the new generation will make it a wonderful country.”85 About the Philippine school exhibit in the Palace of Education and Social Economy, she noted, “Phillipines [sic] are temperate people and have made wonderful advancements in civilization.”86 Laura Ingalls Wilder observed that in the New Zealand display, she and Rose saw “the ugly native islanders that used to be the cannibal tribes in Australia and New Zealand.”87 Both Bruml’s and Wilder’s perceptions of the exhibits reveal a contrast of “primitive” and “modern,” of “horrid knives” and “ugly native islanders” with “improvements” and “wonderful advancements,” that provide the subtext of a clear imperialist project.

Zone concessions featuring peoples of the Pacific also contributed to this juxtaposition of primitive and civilized cultures. Thirty-odd villagers from American Samoa lived from February to September 1915 in the Samoan Village, and a group of Maori lived in the Australasian Village until August. These men and women lived their lives in full public view. A young Samoan man and woman married in an event used to advertise the concession, and a prominent member of the group died, forcing the attraction to close for three days. These Samoan men and women wore clothes, performed work, and lived in homes that accentuated their difference from modern life. Although Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Hawaiians all at times appeared on the grounds and in the papers dressed in Western-style clothes, working and performing activities that were part and parcel of Western culture, the Samoan and Maori performers of the Joy Zone appeared perpetually different, demonstrating their supposed uncivilized status. Local papers printed photos of the Samoan women wearing skimpy clothing or even bare breasted. During their days on the Zone they paddled canoes on a man-made lake, manufactured traditional crafts and handiwork, and danced for visitors. Samoa had no official presence at the fair beyond this concession. As had the displays of Filipinos at previous fairs, no voice offered any variation on this display of Samoan life that was seemingly designed to accentuate the “primitive” nature of native Samoans.

Likewise, the Maori residents of the Australasian Village were presented to visitors as embodiments of exotic others who were still in need of the guiding hand of a civilizing nation. Advertising for the Zone noted the presence of “Maori belles and native warriors,” emphasizing their supposed warlike culture.88 In the first few months of the fair the Daily Program included an ad for the village that suggested its nature: “Australasian Village. New Zealand Maori Carved Village. British Government’s Collection of Maori Carved Houses. A Real World’s Fair Attraction. Native Dancing. War Haka. Poi Dances. Native Games.”89 As with so many of the ethnic villages of other fairs, the Australasian Village offered little nuance; instead, it portrayed the Maori as exotic, primitive others whose lives were reduced, according to the ad, to war dances and games. The concession lasted until August, when it finally proved unprofitable and the attraction folded.

Visitors’ responses to these and other native villages on the Zone demonstrated not only an appreciation of the unfamiliar but also an even stronger sense of the ultimate foreignness of the people therein. After watching a performance of the Samoan Island dancers, Wilder wrote to her husband: “The girls danced by themselves, the girls and men danced together, and the men alone danced the dance of the headhunters with long, ugly knives.” Although she praised the dance, noting that “they were very graceful and I did enjoy every bit of it,” her final remark about their being “covered with tattooing from the waist to the knees” demonstrated her overall impression that they were an exotic people.90 Both Wilder and Bruml remarked on the bodies of those on display, revealing the importance of the body in creating this viewing experience. As Jane Desmond has noted in her work on cultural and animal tourism in Hawai‘i, this sort of tourism “rests on the physical display of bodies perceived as fundamentally, radically different from those of the majority of the audience who pays to see them.”91

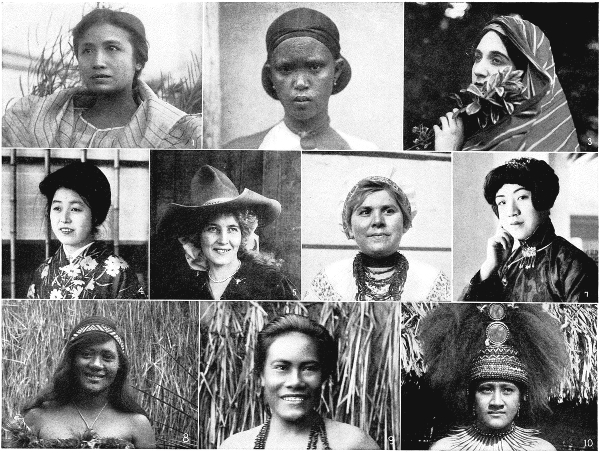

Bodies and physical appearance played a key role in conveying these messages about primitive and civilized to fair visitors. Fair publicity and newspaper reporting continually commented on the physical appearance of Zone performers, particularly of the women. Articles and publicity often stereotyped Chinese and Japanese women, describing them as “dainty” or “exotic” or “doll-like.” Stories reported on their dresses, their hair, and their appearance, reducing them to their physical attributes. Samoan and Maori women were depicted as primitive and backward, with descriptions commenting on their lack of clothing and “odd” habits. Pages on the “South Seas Villages” and on Japan from the magazine section of the San Francisco Examiner each prominently featured women dressed in native costume. According to the report on the Hawaiian Village on the Zone, the “native Hawaiian girls are famous for their dusky beauty and grace.”92 Although the smaller report on the Samoan village featured photographs of both men and women in native costume, the description focused on the traditional crafts performed by Samoan women, implying that the women were the true culture bearers. A similar piece on Japan at the exposition included “pretty native women” as key attractions of the Japan Beautiful concession, alongside “landscape, trees, plants and flowers.”93

Such reporting was typical of publicity that highlighted the physical appearance of the women of color who worked on the Zone. Sometimes its tone was in praise and sometimes in disdain, but it always made an effort to distinguish between these women and the perceived normative white audience. When local feature columnist Helen Dare dedicated a column to the question of “feminine fashion on the Zone,” she began by juxtaposing the “Occident” and the “Orient,” followed by the words “the civilized and the—er—otherwise.” Her description of the clothing of the women of the Zone—Hawaiian, Samoan, Maori, and others—highlighted the visible differences between them and those she perceived as her audience.94 An article on the competition for the queen of the “nine years after [the 1906 earthquake] ball,” in which the women of the Zone competed for the aforesaid honor pointed to the difference and otherness of the contestants. The judge “cannot decide whether the queen . . . should wear a ring in her nose or display a tattooed back.”95 The racialization of these Zone performers reinforced the fair’s emphasis on racial hierarchy and social Darwinism. These women existed, in this formulation, to represent the supposedly authentic traditions of their homelands to fair visitors and to delineate the differences between the exotic or primitive and civilized culture.

Other exhibits across the grounds asserted the progress and superiority of mainstream white American culture. The Race Betterment Booth drew visitors into the Palace of Education and Social Economy, promising visitors that the movement would “create a new and superior race through personal and public hygiene.”96 The booth showcased examples of successful attempts at selective breeding of plants and animals with the suggestion that such strategies be implemented with humans as well.97 The Race Betterment Congress, held during the month of August, focused on the problem of eugenics and drew extensive attention from the press. Another exhibit in the Palace of Education included newly developed IQ tests, informing visitors that scientists could now accurately measure intelligence.98 Films featuring the “flood” of recent immigrants to Ellis Island also implied the need to restrict immigration. Together, these exhibits bolstered support for policies designed to weed out those deemed undesirable—usually nonwhites—and to restrict economic and social opportunities to those deemed fit, usually white northern Europeans. They also reified popular attitudes that American society must exemplify a kind of progress that included the uplifting of supposed lower societies.99

Fig. 19. The Blue Book promised visitors they would see many “types of lovely women on the Zone.” (The Blue Book.)

The narrative of the PPIE conveyed by publicity, rhetoric, statuary, artwork, and Zone attractions emphasized the dominance of white Americans over nonwhites and that of the United States over the Pacific Rim and Latin America. Yet, the multiplicity of official voices—from the Woman’s Board to the governments of foreign nations to territorial officials—meant that this narrative contained considerably more nuance than previous examinations of the fair have revealed. The appearance and performance of young Hawaiian women in the celebration of the Night in Hawaii both validated and subverted the racial messages of the fair. A closer look at the participation of Hawai‘i at the fair reveals that the fair’s official messages about race, gender, and colonialism proved difficult to maintain.

The fair made explicit U.S. claims over its Pacific territories. Haole officials seized the opportunity during the fair to advertise the islands. Historically, white Americans stereotyped native Hawaiians as docile and exotic rather than threatening and savage, allowing tourist promoters to create the trappings of Hawaiian tourism that we know today: pineapples, hula dances, leis, and beach scenes. At the PPIE, the Hawaiian territorial government erected a Hawaiian Building located directly across from the California Building on the northern edge of the grounds. A consortium of Hawaiian pineapple-packing companies funded a large Hawaiian garden and teahouse in the Palace of Horticulture, where visitors sipped pineapple juice and listened to ukulele music. Native Hawaiians had appeared solely on the midway at earlier fairs; however, at the PPIE, Native Hawaiians performed as part of the state’s official representatives.100 Young Hawaiian women served juice and sang to delighted visitors in the Hawaiian gardens, and young Hawaiian men played the ukulele (which became a national fad after the PPIE) in both venues. Meanwhile, on the Zone, entrepreneurs staged a large Hawaiian Village that featured alleged authentic hula dancing.

This dual depiction of Hawai‘i, in both the civilized Hawaiian Building and in an attraction in the primitive Zone, suggests the liminal place of Hawai‘i in the U.S. mind and soon erupted in controversy. A. P. Taylor, the enraged director of the Hawaii Promotion Committee, accused the concessionaire of the Zone’s Hawaiian Village of charging visitors to watch a “vulgar” and “rotten” version of the controversial hula dance.101 American missionaries had long attacked the hula as immoral. By 1915, however, the hula had become accepted as a visible marker of Hawaiian culture that tourism promoters used to promote tourism to the islands. But the vestige of the debate over the hula remained. Taylor and other haole officials wanted to appropriate the hula as an advertising tactic, as they had with the pineapple and the ukulele. But female sexuality was not so easy to contain on the grounds of the fair.

Territorial officials wanted to prove that Hawai‘i was a modern place, where the hula and native Hawaiians were safely tamed. The Zone attraction threatened that goal. Taylor told Moore, “Hawaii is not in the category of the remote South Seas, but it is as up to date and modern almost as San Francisco.”102 His subsequent offhand comment that the few Native Hawaiians involved with the show had quit suggests that they too found the hula performance offensive, although probably for different reasons. Clearly, haoles hoped to use the fair to advertise a modern yet safely exotic tourist destination, unsullied by accusations of immorality, but the desire of mainland Americans to consume the supposedly exotic, morally questionable image of Hawai‘i challenged this goal. PPIE officials agreed to close the attraction, at least temporarily, recognizing the right of haoles to determine the way their home was represented at the fair.

Hawaiian women appeared at the fair as embodiments of the territory’s sanitized and romanticized history and as the key to the haole boosters’ campaign to bring tourism to the islands. Like many women at the fair, they acted as culture bearers both on the Zone and in the official Hawaiian displays. Yet the presence of these young mixed-race women challenged the fair’s racial hierarchy and its larger emphasis on eugenics and race betterment. Whether or not haole organizers intended it, the vision they created of a modern, racially mixed Hawai‘i unsettled the fair’s race and gender hierarchy. These young women were neither pioneer mothers nor eugenic mothers of tomorrow. When young, racially mixed Hawaiian women appeared in Hawaiian celebrations in a stylish shirtwaist and skirt rather than in attire typically associated with the hula, they implicitly challenged the ideals of “scientific marriage” espoused by the supporters of racial betterment. Their identities were not disguised. On the contrary, newspapers chose to publish their full names—often a European first and last name with a Hawaiian middle name—drawing attention to their mixed heritage. A photograph of the dedication of the Hawaiian Building shows more than two dozen young Hawaiian men and women, all dressed in Western clothing and wearing leis while the men carried ukuleles.103 Newspaper readers and fair visitors could encounter young Hawaiian women either dancing the hula or dressed in a typical shirtwaist and skirt. The latter reinforced the image of Hawai‘i as the “up to date and modern” territory that haole organizers sought to depict instead of the remote South Seas image from which they sought to distance themselves.104 A photograph of Elizabeth Victor and Mary Lash, two young women described as “typical Hawaiian beauties,” exemplified this effort. Photographed not in hula outfits but in shirtwaists and skirts and while holding a pineapple, they look very similar to the many photographs that appeared of California women advertising the agricultural bounty of their state. The only distinction was that Victor and Lash were visibly of mixed racial ancestry. Such images inverted the fair’s racial hierarchy in complicated ways and provided a surprising contrast to Adria Imada’s description of how Hawaiian women in the popular culture of the 1920s and 1930s were represented almost solely as “aloha girls” in hula costume.105

One young Hawaiian woman’s actions demonstrate precisely how mixed-race Hawaiians challenged California’s racial politics. Only one week into the fair’s run, local papers announced on February 28, 1915, the impending nuptials of two young people who were in San Francisco for the fair—Amoy Tai, a young Hawaiian woman employed as a singer in the Hawaiian gardens, and her fiancé, Edward Hall, an engineer on a steamship that sailed between San Francisco and Hawai‘i. They were hoping to wed in the Hawaiian gardens before a crowd of well-wishers and fairgoers. Multiple articles in local papers advertised the event. Presumably, Hawaiian organizers and fair officials agreed that the ceremony would lend the blush of romance to the newly opened fair and further advertise the Hawaiian gardens to the fair’s visitors. Their plans were rudely interrupted however, when Tai and Hall attempted to obtain a marriage license at the San Francisco County Courthouse. There, after learning Tai’s father was Chinese and her mother native Hawaiian and seeing that Hall was white, the county clerk informed them that their hoped-for marriage was illegal. California’s antimiscegenation law forbade any marriage between a white person and one of Asian descent. With their license refused, Hall was forced to sail back to Hawai‘i an unwed man.106

Fig. 20. Dedication of Hawaiian Building. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Exactly why no one mentioned to Hall and Tai that their marriage would be illegal under California law remains a mystery. Presumably fair officials were consulted regarding permission to hold the wedding in the Palace of Horticulture. Newspapers reported on the impending event with no mention of legal hurdles despite including Tai’s name and picture, both of which clearly indicated that she was Asian. Were the would-be-weds, fair officials, and journalists all ignorant of the laws? Or did they assume that the county clerk would ignore the laws in order to please fair officials? We do not know. But this nonevent reveals the contradictions that the fair’s welcoming of the Pacific world and its peoples had produced. Had this wedding occurred, it would have undermined the Palace of Education and Social Economy’s exhibits promoting eugenics and scientifically planned marriages and called into question the fair’s racial hierarchy. That it did not demonstrates the extent to which California’s political culture extended to the fairgrounds.

The PPIE celebrated the dominance of San Francisco and the United States over the Pacific and reflected the goals of local and national fair boosters, foreign nations, and international businesses. Despite the dominant images of California’s having been successfully conquered by white pioneers and Catholic padres, of a Pacific under peaceful U.S. control, and of women dominated by men, alternative visions appeared, as Argentina’s exhibit and the example of the Hawaiian attractions suggest. Voices, both foreign and domestic, created the vision of California and the Pacific that appeared at the fair. On the local level, from the moment San Francisco won the fair in 1911, many voices also weighed in on how the event could best serve the city. Where should the fair be located? How much should it cost? Should it favor tourists or residents? Just as multiple official voices created the fair, so too did multiple community voices challenge fair officials about the fair’s relationship to the city. These debates reflected current concerns about public good versus private profit and demonstrated that the fair became a lightning rod for local political issues and global economic interests. To their dismay, local residents frequently discovered that the economic interests of fair officials would be paramount in resolving these debates.