Uniting San Francisco

San Francisco’s “joy bells rang, her streets and her bright cafes swarmed with revelers all night, and her street-sweeping squad took wagon-loads of confetti off the pavements the next day” after President William Howard Taft signed the resolution granting San Francisco the right to hold the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.1 This united joy in winning the battle with New Orleans for the fair faded, and soon San Franciscans “plunged into a good old family row as to the best place to put the fruits of victory.”2 Although most fair boosters and city residents assumed that Golden Gate Park, the site of the 1894 Midwinter International Exposition, would host the event, fair officials had not decided on a site. Serious questions remained about whether the park could, or should, support a large-scale exposition and whether other sites in the city might be more appropriate and affordable. The city’s momentary unity at winning the fair dissolved as it became clear that some San Franciscans and fair officials disagreed about how the site of the fair could best serve the city.

The debate over the site of the fair raged in newspapers, in neighborhood and city council meetings, and on the streets of San Francisco for most of 1911. Debates about the availability of transportation, the location of saloons, and the regulation of hotels also emerged. Once the fair opened, citizens criticized the price of the fair and, ultimately, the relationship of the fair to the city. Was it a true public celebration to be shared by all residents, or was it simply a huge show staged by elite boosters that privileged the wealthy? The resulting discussions about public good and private profit in the city encapsulated the tensions facing Progressive Era political leaders who sought to expand public services while also meeting their own desire for financial gain. City residents and interest groups repeatedly seized upon the fair as a way to reshape the physical and social geography of the city. They all eventually discovered that their success depended on whether their plans fit the larger economic goals of the fair management.

Residents inundated exposition officials with proposals for possible fair sites. The suggestions varied from the unworkable—Goat Island, Alameda Flats, and Tanforan—to the elaborate, such as a dual-level waterfront site suggested by Senator Francis Newlands of Nevada.3 By mid-summer, the debate narrowed to three possibilities: Harbor View, Golden Gate Park, and Lake Merced. The prolonged debate occupied the front pages of city papers and the agendas of local clubs for months. Residents sought to convince fair officials to locate the event in a place that would meet the long-term needs of city residents rather than the temporary needs of tourists or the financial exigencies of the fair. Officials claimed to weigh such issues as the cost of securing the necessary lands, the time before the land could be appropriated for grading and construction, the climate, the long-term results of occupying the site, the view, and the convenience of the site for both residents and visitors.4

Many believed that Golden Gate Park offered the only appropriate location because the event would leave the park with concrete improvements that would benefit city residents for years to come. Since the propaganda issued during the campaign for the fair and the local bond issue passed to fund the fair all mentioned Golden Gate Park as the site, this assumption was not unwarranted. As the focal point of the city’s outdoor activities, and the pride of city residents, the park seemed the logical location. Many previous expositions, including the recent 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, had been held in city parks.5

Golden Gate Park contained a few permanent buildings, athletic fields, playgrounds, and some landscaped areas in 1911. The buildings included relics of the Midwinter Expo, such as the Japanese Tea Garden and Art Museum, while the western end of the park remained undeveloped. Some local residents, such as the exposition vice president and San Francisco Chronicle publisher (and the mind behind the Midwinter Expo) Michael de Young, assumed that the PPIE offered another opportunity to further develop the park. “Golden Gate Park was intended for a people’s pleasure ground,” argued one Chronicle editorial, “and not for a wildwood. It was meant to be used in a manner calculated to give enjoyment to the greatest number.” The Chronicle, and presumably many residents of the city, favored this developed model of the park, with “flower beds, lawns and playgrounds,” rather than the wild forest that then existed in the western, undeveloped section under question.6

Not everyone agreed with de Young’s vision. In early May, William Hammond Hall, a local civil engineer and first superintendent of the park, provided exposition officials with the drawbacks of using the park. He argued it would permanently wipe out part of the grounds and cost the city (and thus citizens) a great deal to rebuild and relandscape the park after the fair ended.7 The debate over whether to locate the fair in the park was part of a larger debate about what kind of good the park should bring the city. Should it be a carefully landscaped site of museums and playgrounds, or should it be a forest park, with significant portions left undeveloped? The discussion reflected larger Progressive debates between those who favored romantic versus rationalistic parks.8 In keeping with Progressive Era concerns about social disorder, backers of the rationalistic model urged that these well-ordered spaces were necessary counterpoints to the dangers of urban life and composed a key part of “their formula for encouraging a good society.”9 Reformers believed that such parks offered city residential activities a needed focus for recreation. Many San Franciscans agreed that the concrete benefits the fair might bring—stadiums, museums, paths, and landscaped areas—would be more useful to city society than the wild dunes at the western edge of the park would be.

The PPIE Board of Directors surprised many city residents in May 1911 when it published a report that favored not Golden Gate Park but Harbor View as the fair’s site. The Harbor View area was on the northern edge of the city, bounded by Lyon Street, Lewis Street, Laguna Street, Bay Street, Van Ness Avenue, and Lombard Street and with the bay on the north. The region served as a recreation area for the city in the 1880s, hosting the popular Harbor View Baths, but the lack of accessible transportation caused a decline in its popularity. The baths closed in 1909 when the city decided to extend Lyon Street to the bay so it could begin to incorporate the area into a tax assessment district, a move that suggested the city’s desire to further develop the neighborhood.10 Some described the neighborhood as an “eyesore” for those wealthy San Franciscans in Pacific Heights who dwelled above it. Harbor View housed a mixed neighborhood of industry, boardinghouses, saloons, earthquake cottages, and other structures built as emergency housing after the 1906 disaster.11 One former resident described the area as “a place we, as kids, liked to go to collect old scraps of metal such as window weights and other discarded articles to sell for pennies in the years we lived in Cow Hollow as refugees from the Earthquake and Fire of 1906.”12 Acres of what would be the exposition site were still underwater and would need to be filled in with soil to expand the available land for the fair.

The earthquake and fire reshaped Harbor View. Tons of refuse and rubble were dumped in the sparsely populated area during the rebuilding process and would eventually become the fill necessary to making the site buildable for the fair. Since the neighborhood and the adjacent Presidio had extensive open space, they had housed multiple refugee camps. The last camp closed in 1908, but earthquake cottages and shacks remained sprinkled throughout the southern part of the site. The city’s Health Commission forced one owner of hundreds of refugee shacks in the neighborhood to move the buildings and evict his indigent tenants in the fall of 1911, again indicating the city’s desire to spruce up the area.13 Many of the northern blocks remained underwater, awaiting the dredging and filling that would make them usable. No fire insurance company maps were produced between the earthquake and 1912, when the PPIE began to raze the buildings on the site. But 1905 maps from the Sanborn Map Company reveal the neighborhood comprised primarily two-flat residences, suggesting it included a large number of rental properties. Significant large-property owners included the Fulton Iron Works and the Pacific Gas and Electric Company.

Although it was the only proposed site with significant buildings, the board’s report dismissed their importance, because those buildings were of negligible value. Of the 540 buildings on the site, 263 were “the poorer and cheaper type of buildings.” Half of the remaining 277 structures were located on the site’s southern edge and might easily be excluded from the grounds. The total buildings cited, however, did not include the area’s “refugee shacks and sheds.” Given that the owner approached by the Health Commission had 144 such buildings on the site, it is likely that far more buildings were eventually razed or moved to make way for the fair.14 Nor did the figure include the buildings of the Fulton Iron Works, the United Railroads, or the San Francisco Gas and Electric Company.15 The report’s writer evidently expected that the exposition would be able to secure the cooperation of local industries without a problem.

The report offered clear arguments against other possible sites. Islais Creek, an area of about 400 acres that lay west of Kentucky Street and south of Army Street, was completely inappropriate. Not only would the marshland require a huge amount of fill to turn it into solid ground, but also it was too close to “Butchertown” and would therefore expose visitors to “unattractive portions of the city.” Sutro Forest posed the opposite problem. Although currently undeveloped, the report concluded that it would “probably be a future high class residence section,” whose owners might require significant restoration work after the fair, adding an indeterminate cost to the endeavor. The preservation of a potentially wealthy neighborhood trumped any desire to develop the location for the fair. Harbor View soon emerged as the cheapest site despite its large number of existing structures.16

Neither the report on the sites nor the fair directors appear to have ever considered the fate of those city residents who lived in Harbor View. The public debate over the site never mentioned the San Franciscans who lived in Harbor View or their opinions on having their neighborhood turned into the exposition site. This working-class neighborhood, though, may have been one that its neighbors in Pacific Heights were all too pleased to eradicate.

City residents and interested parties continued to vigorously debate the issue for the next two months. The active engagement of the city’s many neighborhood associations indicates the passion with which many San Franciscans approached the issue. Residents spent a great deal of time explaining why the site nearest to their particular neighborhood was the only suitable place for the fair. These claims often contradicted each other. The North Beach Promotion Association (located near the Harbor View site), for instance, told fair officials in April that Harbor View was the best choice because it had the best climate, was easily accessible for night-time revelers, and was located close enough to downtown to benefit merchants, whose interests were “paramount.”17 The Park Richmond Improvement Club boosted Golden Gate Park, asserting that “the park is the most accessible, the space is ample, it is the people’s choice, will get the greatest gate receipts, and is where we can best exhibit the lord of oceans, the mighty Pacific.”18 A site’s suitability depended on one’s location in the city.

Financial gain remained at the root of these arguments. Many asserted that the most important long-lasting effect of the fair would be to raise property values in the city. Newspaper reports on the stagnating real estate market in early 1911 attributed the problem to an uncertainty about the fair site. This condition persisted throughout the spring, particularly in the currently underdeveloped outlying areas of the city that might suddenly be located near the exposition site. City real estate agents were probably quite eager to have the question decided.19

Many residents believed the fair would profoundly affect the city’s residential development. One San Francisco real estate agent informed department store president Reuben Hale that the city would provide the much-needed housing for the “great middle class” only if the fair occurred in the park. The fair would prompt the development of the areas lying to the north and south of the park, drawing back some of the residents who had fled the city for the East Bay after the earthquake. Harbor View offered no nearby desirable neighborhood ripe for development; instead, he worried, it might boost the cities across the bay.20 Others feared that Harbor View’s easy accessibility to the East and North Bay areas via ferries would hurt owners hoping to lease their city properties during the fair’s run in 1915.21 Those who boosted the Lake Merced or Sutro-Merced site also stressed that residential development would be a permanent legacy of locating the fair in the southern part of the city.22

Opponents to Harbor View latched onto the concern that the site might benefit cities outside San Francisco more than the city itself. One park booster wondered, “What is the use of our hottells [sic] and all our apartments, when the people can live in Oakland and all the cheap towns and you want to make it so they do not have to come to the city at all and you want to make it so all our . . . horses and teams lay idle we want the fair at the park and that’s what will benefit San Francisco.”23 Memories of the recent Oakland campaign to depict the city as the region’s transportation hub likely heightened those anxieties. When Oakland portrayed itself as “as the potential supplier of goods to the Orient . . . a transfer point for transcontinental freight destined for Pacific ports . . . a strategically situated port . . . as a market for the great producing areas of the Pacific Slope, and . . . as the gateway to the fertile interior valleys of California,” it directly challenged San Francisco’s claim to regional and Pacific dominance.24 Locating the fair on the city’s northern edge and in an area not yet effectively connected to the rest of the city through public transportation seemed a risky proposition to those city residents who wanted the event to bring prosperity to their own neighborhoods. East Bay residents, however, eagerly boosted the site, suggesting that the ease of transport across the bay would bring more visitors and workmen to the fair.25

Harbor View had plenty of supporters. Many downtown business owners favored the site because it was located close to downtown. They assumed that new rail lines would make it easy for tourists to travel back and forth between downtown and the fair. A group of property owners from the downtown “burned district,” the Hotel Men’s Association, and the Chinese Chamber of Commerce each passed resolutions favoring Harbor View, demonstrating that a variety of powerful business interests united behind this plan.26 They boosted the Harbor View site because of its proximity to downtown and because of its lovely views and bay-front location. A fair fronting the city’s gorgeous Golden Gate seemed the only appropriate location for a fair celebrating maritime commerce and the Panama Canal.27

Arguments soon grew ugly as allegations of bribery and graft surfaced, echoing the civic upheaval of the city’s 1907 graft trials and stirring up debates about the difference between public good and private profit. Some residents objected because the property at Harbor View was privately owned unlike the publicly owned park site. Using public money subscribed to the fair to improve private property struck many as unfair. One angry citizen argued that having the fair at Harbor View would “benifit [sic] a few million heirs [sic] and fix up there [sic] property.”28 Such charges were not necessarily unwarranted since only three wealthy owners held title to a large chunk of the site still underwater.29 Another writer accused then-acting exposition president Hale that “you can now afford to associate with people who own large interests and want those interests served by using the money of the people to fill up mud-holes and take away an eye-sore that has bothered some of the people who live on Broadway and Pacific Heights.”30

Fig. 21. Map of San Francisco showing exposition grounds. (Courtesy of the Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Meanwhile, de Young and the San Francisco Chronicle continued to back the park site. The paper published a number of articles insinuating that the campaign for Harbor View was led by unidentified “real estate interests” that sought to profit at the cost of the public good. After the city engineer’s office prepared a secret report comparing the Harbor View and Golden Gate Park sites, the Chronicle charged, “It is a well-known fact that two or three real estate concerns are interested in pushing before the people the site designated as Harbor View, one-third of which is under water.”31 Shortly thereafter, attendees at a meeting of the Federated Improvement Clubs alleged that the plan to locate the fair at Harbor View was the result of a real estate scheme. They called for Governor Hiram Johnson to interfere in favor of Golden Gate Park.32 The group again agitated against Harbor View advocates a week later, accusing them of deliberately misrepresenting the costs associated with the Harbor View site.33 The Chronicle took its allegations a step further in mid-May. An article published in the real estate section argued, “It is generally understood in real estate circles, too, that certain operators have, to use a term of the business, ‘loaded up,’ with propositions in the vicinity of Harbor View. . . . Real estate agents have said that practically everything available in the way of real estate in the north end . . . has been secured under options for some time.”34 These articles stirred up resentment against supporters of Harbor View and created the sense that only those with some personal interest in the property preferred the site.

Exposition directors and city residents continued this rancorous public and private debate until a new option finally emerged in late June. This new plan proposed holding the fair in both Golden Gate and Lincoln Parks. The solution appealed to those who feared that Golden Gate Park would not have enough acreage to meet the needs of the event, for this option offered roughly a thousand acres.35 De Young presented the idea before the Board of Directors, and the members responded with interest.36 A call went out for the owners of those intermediary blocks to come forward and agree to lease their land to the exposition, and the San Francisco Chronicle began to boost this new plan with great vigor.37

On July 15, 1911, a unanimous vote of the directors approved a composite site that included Golden Gate and Lincoln Parks and Harbor View. The plan integrated ideas inspired by the pre-earthquake work of city planner Daniel Burnham into an elaborate call for a re-imagination of much of San Francisco.38 Harbor View would be the site of the amusement district of the fair since it was located close to downtown. Lincoln Park would host a “giant commemorative statue” and be linked to Golden Gate Park by purchasing the block that divided them. The bulk of exhibit buildings, such as city, county, and national buildings and “especially . . . the Oriental exhibits,” would be erected in Golden Gate Park. A permanent art gallery and athletic stadium would be built in the western edge of the park. Buildings in the park would be used “so far as possible for permanent improvements and such other exhibits as would be least destructive, and add most to its beauty.” A lavish civic center downtown would be erected near Van Ness Avenue. Finally, the plan recommended that from the Ferry Building on Market Street to the Van Ness entrance to the fair, “such decorations be featured . . . that a visitor . . . would feel that he was entering an Exposition City.”39

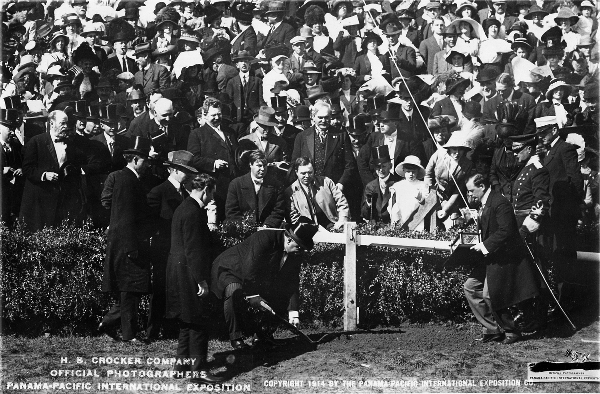

This site seemed to please everyone. The San Francisco Chronicle triumphantly stated, “Location Assures Permanent Improvements in Both Parks; Magnificent Marine Boulevard: Scope of Exposition Plan Surpasses Expectation.”40 Members of the Board of Directors issued glowing public statements that lauded the site. M. J. Brandenstein stated, “We have adopted the plan that makes San Francisco the greatest exposition city in the world. . . . The plan is unique and embraces the best features and advantages of San Francisco.”41 In October 1911, President Taft broke ground for the PPIE in Golden Gate Park, in keeping with the assumption that the fair would be located there; yet the exposition took place completely at the Harbor View site.

Little of the elaborate plan envisioned in the summer of 1911 ever developed because fair directors continued to explore the relative cost of various options. Finally, in December, the Executive Architectural Council of the PPIE submitted a report comparing the costs of three options: Golden Gate Park only, Harbor View and the Presidio, and the combined plan. According to their estimates, building the fair in Harbor View and adjoining government lands would cost over $1.2 million less than building it in the park and $1.9 million less than the combined plan. Significantly more money could then be spent on the buildings themselves. Moreover, the report continued, the experiences of other recent fairs suggested the value of a compact site for retaining visitors’ attention.42 The council recommended holding the fair only at Harbor View, and on December 15, 1911, the exposition directors approved a plan to erect all exposition buildings at the Harbor View–Presidio location, demonstrating the triumph of financial imperative over the will of city residents.43 Popular discontent continued in some quarters. In January a meeting of neighborhood improvement groups approved a resolution calling for the fair to be held in the park rather than at Harbor View, since the buildings could be retained for the public’s future use.44 Yet when local papers published the drawings of the proposed grounds in May, they were accompanied by celebratory comments and descriptions of the proposed features of the grounds with nary a comment on their location. The public debate was over.

Fig. 22. President Taft breaking ground in Golden Gate Park, reflecting the dominant assumption that the fair would occur there. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Clearly many San Franciscans felt deeply invested in the fair, and they believed their voices should be heard in the debate over the site. Although they might agree the fair should benefit the city, they could not agree on how the fair should do that. The outpouring of support for Golden Gate Park versus Harbor View reveals that many San Franciscans believed the fair should bring concrete benefits to all city residents, not just to wealthy investors. Those imbued with the progressive spirit favored a rationalistic type of park and believed that locating it there would leave a legacy beneficial to park enthusiasts. The Harbor View site conveyed benefits solely to private landowners. Yet the fair was ultimately a private venture—run by a private corporation but funded by public subscription—and as their ultimate decision reflected, the fair directors had no responsibility to city residents to design the fair to serve their needs.

The rationale that Harbor View would be cheaper and more scenic did not appease those who believed that locating it on private land was a betrayal of the public trust. In the proposal for the composite site the Board of Directors had delineated its definition of the relationship between the fair and the city. They stated that the fair must be located somewhere that was easily accessible to all parts of San Francisco and not simply to the surrounding area. It should leave “the greatest possible number of real permanent improvements” and should help to build up the city generally rather than focusing on boosting one particular location. But the location of the fair at Harbor View did little to advance these goals. The site did not yet have a streetcar connection to the rest of the city. The private ownership of the land meant any improvements to the neighborhood might not be accessible to city residents in the long term. Nor did the board clearly explain how this site would build up the city. This contradiction called into question the fair directors’ dedication to the city’s public good. The lingering history of the graft trials and the allegations of corruption and bribery they unearthed only four years before exacerbated this debate, raising unsettling questions about the goals of fair directors. Rather than bringing the city together, the debate over the site reinvigorated existing debates about public good and private gain.

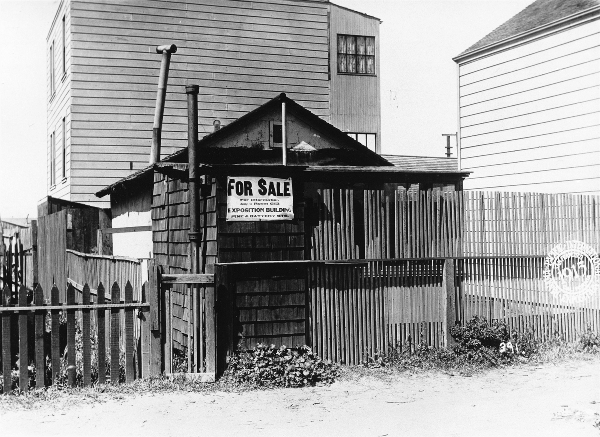

Once the site was set, fair officials had to acquire legal rights to the property. Fortunately, local neighborhood improvement groups already had solicited lease agreements from many property owners during their lobbying efforts. The groups’ work eased the way for fair officials, who then had to convince only a few recalcitrant owners to make their property available to the fair.45 This process occurred fairly easily. Most property owners likely believed, as one group of owners told officials, that the fair would bring a clear “increase in value” to their property.46 For the more reluctant owners, the land department adopted a policy of “delaying settlements of leases for the time being” in the hope that those demanding higher prices could be convinced otherwise as the fair removed houses and as they witnessed the “gradual depopulation of the neighborhood.”47 Eventually, the legal department filed condemnation suits against a few owners that ironically resulted in smaller judgments than the fair officials originally offered. Whatever their tactics, fair officials eventually obtained title to all the necessary lands, gaining 330 acres from 175 different owners. The entire operation cost the fair almost $1.2 million.48 Most of the land was procured by paying a monthly rental fee and property taxes. Other owners settled only for tax payments, and in a few other cases the PPIE bought the properties outright. Once the land was acquired, any existing improvements had to be removed. The fair disposed of more than 400 structures, “ranging from a 50 room apartment house to a fisherman’s shack,” through both auctions and private sales.49

Fig. 23. A Marina home purchased by the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

This process forced hundreds of people living in the site’s southern portion to relocate during 1912. Some went willingly, but others resisted and resented the fair’s appropriation of their homes. Since many buildings were rentals, those actually living on the property did not make the decision to lease or sell the land. This situation resulted in a confusing relationship between tenants, owners, and the fair. A PPIE land department report indicated that one resident, a Mrs. Castiglione, was “unable to speak English and does not appear to understand about moving,” while A. Penazzio’s residence also included “parties [who] do not seem to understand that they must move.”50 Four tenants of rentals on Van Ness refused to pay their last rent payments since they knew they would be evicted shortly.51 Other renters resented the difficulties caused by moving. Mrs. Ida West Hale wrote to Mayor James Rolph in February 1912, asking if he could provide financial assistance to her and her husband, who were both in their seventies and faced a move from their residence on Van Ness.52 Mrs. Mary Suters likewise wrote an eloquent letter to the PPIE Board in which she cited the difficulties she had endured since the earthquake had left her penniless. She supported her two sons by taking in boarders, but she would have to double her rent and lose half her boarders upon moving. Could she therefore, she asked, be released from her last month’s rent? Alas, replied Director of Works Harris Connick, this request was impossible.53

Fair officials dealt with property owners far more generously than they did with renters like Suters. A number of letters remain from other residents who faced serious financial difficulties, but in no case did fair officials offer any financial assistance to renters affected by these circumstances. Harbor View grocer Frank Fassio worried about how to restart his business in a new location and received early promises of assistance from fair officials. Fair officials told him in March 1912, however, that despite their regret about his hardship, they had “no authority to use any of the Exposition money for anything except for the regular Exposition business.”54 Yet when Harbor View saloon owner Mr. Driscoll resisted the fair’s attempt to obtain the land on which his saloon was located, the fair went to great lengths to gain the property. They not only paid him for the land but also moved his saloon, home, and personal property for no charge.55 They justified this expense by the need to acquire his land, while relieving working-class San Franciscans of their rent (often $20 to $50 a month) was not a priority.

No records detail what these displaced San Franciscans thought of the PPIE after it opened, but their stories remind us that these events occurred at a human cost. Property owners likely benefited from the improvements made to their property and having their taxes paid for four years. Low-wage renters faced a much more challenging situation, losing their homes and sometimes their businesses at short notice. According to an official of the PPIE land department, no residents were “forcibly ejected in the true meaning of such an expression. Three of the people were a little stubborn about giving up their premises even after the buildings had been sold to wreckers. We did not turn the people out forcibly but the wreckers removed the houses while the owners were still occupying them.”56 Whether these three resisters were owners or renters is unclear, but plainly not all Harbor View residents welcomed the fair.

Fig. 24. Construction site of PPIE. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

The fair transformed the neighborhood surrounding Harbor View. Thousands of people came to the area each day, offering enterprising San Franciscans a host of business opportunities. As local columnist Ben Macomber reminded readers after the fair opened, inside the grounds was “an orderly exhibition of all the best and latest that modern civilization and progress have produced. Outside is a jumble of hucksters, purveyors, merchants, fortune tellers, jitneys, bootblacks, steerers for automobile parks, hot dog men, peanut venders, newsboys, souvenir sellers, chafferers of every description.”57 The fair’s prohibition on automobiles on the fairgrounds meant that auto-owning visitors had to park their cars elsewhere. The solution? To turn vacant lots into parking lots and gas stations, which offered huge profits to those who held out long enough on renting their lots to eager businessmen. Other aspiring entrepreneurs opened lunch counters in “every little hole in the wall,” first serving the five thousand men who built the fair and eventually serving the thousands of daily visitors who decided the food on the grounds was too expensive. According to Macomber, the “outside fair” was as cosmopolitan as the inside fair, with immigrants of every description flocking to the neighborhood to set up shop.58 The PPIE revamped this neighborhood, a process that reveals the unintentional economic and social consequences of the fair, as well as the ingenious ways local residents took advantage of the event.

Just how to get those thousands of people to Harbor View posed a major challenge for fair and city officials. No major streetcar lines ran near the proposed fair site. The closest stop to any fair entrance was located a thousand feet away, a distance judged inconvenient for most tourists. Existing lines could accommodate only 13,500 passengers an hour. How would the tens of thousands of people expected to journey to the fair each day reach the site?59 The question of transportation and the possibility of expanding existing street railway lines in the city occupied city officials, fair directors, and city residents during the spring and summer of 1913, and it offers another window into the relationship between the fair, urban development, and conceptions of public good in San Francisco in the 1910s.

San Francisco’s streetcar system had been a thorny political issue since the turn of the century. City officials debated the merits of municipal ownership amid allegations of corruption and bribery levied at United Railroads, the corporation that controlled most of the lines in the city. The city’s reform charter of 1900 declared that it was “the purpose and intention of the people of the City and County of San Francisco” to acquire ownership of its public utilities.60 The 1913 Board of Supervisors had been elected on a platform of municipal ownership, a position that responded to the city’s frustration with the influence of United Railroads. In 1902 the company had acquired control of 226 miles of track and roughly a thousand cars, or nearly all of the lines located in San Francisco. Three years later, company president Patrick Calhoun sought to convert all of its lines to electricity. After the 1905 victory of the Labor Party, local political boss Abe Ruef informed Calhoun that a $200,000 payment would ensure the Board of Supervisor’s approval of the electrification plan. Witnesses revealed this bribe during the graft trials, enraging city residents and triggering a Carmen’s Union strike against the Union Railroads. Calhoun’s vicious strike-breaking tactics then angered the local labor community. His antilabor stance and corrupt business practices helped boosters of municipal ownership to make their case. Voters finally approved two bond issues in December 1910 to acquire the Geary Street line, which Union Railroads did not own; to convert it to electric cars; and to extend it down Market Street. Thus was San Francisco’s Municipal Railway, one of the first in the nation, born.61

Exposition officials stepped into this heated political context as they sought to convince the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to approve the construction of new streetcar lines to the exposition grounds. Fair directors argued this project was essential for the public good of the exposition and, by extension, the city. A February meeting between PPIE officials and the Board of Supervisors hinted at the political battle ahead. “I certainly believed,” President Charles Moore stated, “that our activities would be confined within the fence surrounding the grounds. And [I] had no idea that the city would not look after the transportation . . . problems that confront us.” Supervisor George Gallagher rejoined, “The fair directors did not ask this board where to put their fair. . . . And I do not want any stigma left with this board on account of any action they may have taken.”62 Fair directors did not ask for municipal ownership; rather, they simply demanded that the city devise a way to transport the anticipated crowds to the Harbor View site. This meeting jump-started an active citywide debate about to how to solve the city’s transportation problem.

Fair officials remained neutral about the question of municipal ownership. Boosters of public ownership quickly seized the opportunity to campaign for the expansion of municipal lines. A few days after the meeting between supervisors and fair officials, the San Francisco Examiner published an elaborate plan to solve the exposition’s and the city’s transportation problems. It called for four new publicly funded streetcar lines to bring visitors to the fairgrounds and to reach residential districts underserved by the rail system.63 This solution, the paper promised, would solve the immediate transportation problem, bring profit to the city, and “free the city from the very obvious peril of being forced into undesirable franchise grants,” such as those with the United Railroads.64 Public reaction to the plans was immediate and positive. Mayor Rolph and many members of the Board of Supervisors and local improvement organizations all supported the plan.65 The Harbor Commission announced it would seek state funds to construct a double-track railroad along the Embarcadero, with a tunnel under Fort Mason, to reach the exposition grounds.66 Exposition directors responded to the plan cautiously. Board members publicly refused to endorse municipal ownership. They simply reiterated the necessity of finding “any solution that will give us the service.”67

City politicians and residents debated the question of the streetcar lines and of municipal ownership throughout 1913. Conservatives, who regarded the idea of municipal ownership as a small step from socialism, found the idea repugnant. Many others in the city, however, eagerly embraced the plan. The Examiner’s proposal soon gained momentum and evolved into a plan calling for nine new streetcar lines, which would be funded by a bond issue of $3.5 million.68 The Board of Supervisors, local improvement groups, and other proponents of municipal ownership joined forces and called for passage of the bond issue. In disagreement stood the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce and a number of conservative businessmen—the peers of the fair directors—who opposed the idea of municipal ownership on principle. Other opponents argued that the plan was too expensive and insufficient to meet the needs of the anticipated exposition crowds. The plan’s supporters brought together diverse interests in the city, from the Labor Council to those businessmen who saw the profitable municipally owned Geary Street line as proof that public ownership could bring real benefits to the city.

Despite widespread support for the measure, the exposition directors continued to refuse to take an official stand in support of public ownership. Their stance infuriated both the mayor and the Board of Supervisors. In late May as the bond issue heated up, the exposition directors formally resolved that “the Exposition Company shall remain neutral in the matter of said proposal and that it refrain from participating in any attempt to influence public opinion for or against said proposal.”69 Some directors outright opposed municipal ownership and resented that they were being forced to support it to gain the desperately needed transportation for the exposition. Others did not wish to support such a widespread expansion of the rail system. Still others argued that the funding offered by the bond issue would not be sufficient to provide enough transportation to the grounds.70 Although President Moore and other directors repeatedly asserted that the debate was not about municipal ownership, the subtext of the debate over the neutrality resolution was clear. Many of the directors perceived a chasm between their political beliefs and those of the Board of Supervisors. They resented the supervisors’ attempt to use the exposition to gain a political goal, an expanded municipal railway. Despite Rolph’s fervent plea to support the bonds, the neutrality resolution passed by a vote of twelve to six.71

Public resentment against the fair directors’ unwillingness to take a stand increased. The Board of Supervisors responded angrily to the neutrality resolution, resolving that since the Board of Directors’ statement was “tantamount to a declaration that it has no interest in securing adequate passenger facilities for the exposition, and has no interest in relieving San Francisco . . . from the intolerable street-railway conditions now existing . . . be it resolved . . . that . . . the Board of Supervisors, deprecates the act . . . [of] taking a neutral stand on a question of such vital importance to the exposition and the city and county of San Francisco.”72 One supervisor argued that the directors’ sympathy for the United Railroads clouded their ability to put the good of the city before that of their private interests.73 The majority of the directors were conservative businessmen, and one of them was an assistant to the president of United Railroads.74 Many probably had personal, if not also business, ties to the United Railroad Corporation that likely affected their opposition to municipal ownership. Fair officials thus found themselves in a double bind. Should they publicly oppose a measure that might threaten their personal financial interests and contradict their personal beliefs, even if it would bring success to the exposition? A neutrality vote thus offered them a way to remove themselves from a situation to which they saw no easy answer.

The citywide August bond measure passed by a strong majority, 51,569 to 13,700, despite the exposition officials’ lack of enthusiasm. It carried equally in neighborhoods around the city, suggesting that most San Franciscans were united behind municipal ownership. Rolph heralded the vote as a sign that his vision of a “united San Francisco” and a “real live Exposition” was being realized.75 But the campaign against the bonds revealed the bitter divisions in the city between progressives and conservatives and the extent to which the fair became a flashpoint for political conflict as it reinvigorated old debates about municipal ownership and corrupt business practices. It demonstrated again that the economic success of the exposition was the fair officials’ bottom line. They refused to oppose municipal ownership openly, even though it contradicted many of their political beliefs, because they knew that the project would help ensure the success of the fair. In this case, then, the fair directors’ desire to make the fair profitable forced them to make concessions to boosters of municipal ownership. In so doing, they dramatically changed the shape of San Francisco, bringing public transportation to many new neighborhoods and enabling the eventual development of the exposition site as a residential neighborhood in the 1920s.

In their effort to make San Francisco into an “Exposition City,” the fair directors intervened more directly in the practices of two local businesses—saloons and hotels. The exposition purchased a number of saloons as they acquired the land at Harbor View both because they needed access to the land and because they saw a benefit in removing businesses associated with vice and immoral practices from proximity to the fair. Some boosters worried that San Francisco’s reputation as a stronghold of the liquor trade, along with its active vice district, threatened the success of the exposition. The city remained a solidly “wet” city throughout the Progressive Era even as agitation for temperance increased across the state and nation in the early 1910s.76 Fair directors saw no reason to ban alcohol from the grounds, but they realized that having saloons—and their working-class patrons—nearby might concern reform-minded middle-class visitors. These establishments might draw other visitors and their money away from the grounds, so exposition officials were eager to move saloons as far away from the fair’s entrances as possible.

Despite not being truly dedicated to the tenets of moral reform, fair officials appropriated the movement’s rhetoric to oppose saloons near the grounds.77 Officials feared that working-class saloons would be a bad influence “upon those whose business or pleasure calls them to the Exposition grounds.” Further, according to one official, “it cannot but hurt the fair name of the City of San Francisco if the precedent is established of permitting the operation of saloons near the entrances to the grounds.”78 Such statements echoed concerns that working-class saloon culture threatened the moral order of the city and the fair. Local residents also weighed in. One man told Moore that he and others feared that “extraordinary efforts will be made to establish liquor saloons WITH THE USUAL ACCESSORIES” in the neighborhood near the grounds, so they wanted the exposition to take action against these potential threats to the “character and reputation and incidentally the value of their property.”79 For some residents the fair offered an ally in the fight against saloons and their clientele. San Francisco had a long history of establishments that provided free-flowing alcohol to all comers. Fair officials believed in this case that it was more important to cater to the sensibilities of elite and middle-class tourists than to the needs of working-class city residents who patronized these saloons.

That fair officials were motivated by any devotion to the principles of temperance is unlikely. Fair officials opposed making the fair itself “dry” and, reflecting the city’s widespread use and tolerance of alcohol, opposed a statewide temperance bill in 1913. Although progressive good government measures found support in San Francisco, moral reformers faced a much tougher battle in the city. No evidence exists to suggest that this particular opposition to saloons was motivated by anything other than a desire to remove potential competition for tourist dollars from the neighborhood of the fair.

Moore argued during the fight over transportation that the board sought only to address issues contained within the fairgrounds, but the saloon issue revealed that claim to be patently untrue. As the PPIE acquired land at Harbor View, the fair board wielded its political muscle to demand that the Police Commission inform it when anyone petitioned for a liquor license on the land designated for the exposition.80 Officials feared that the establishment of a new saloon on desired land would make it prohibitively expensive for them to acquire the relevant parcel.81 The Police Commission cooperated and periodically sent lists of potentially objectionable saloon applicants to the Board of Directors for review.82 Fair officials shaped the development of the neighborhood outside the gates of the fair, all in an attempt to make the PPIE profitable.

Frustrated saloon owners, and presumably their clients, resented the fair’s interference. Some displaced saloon keepers petitioned the police commissioners for new space located as close to the fairgrounds as possible. Adolph E. Schwartz repeatedly asked for a space directly opposite the Fillmore Street entrance to the fair. Upon receiving confirmation from exposition officials that they absolutely opposed any such licenses, “regardless of the character of the saloon,” the Police Commission vetoed his petition.83 The commission finally informed the exposition in March 1914 that it would not grant any more saloon licenses near the fairgrounds to those owners displaced by the exposition. The police refused to meet the demands of those saloon keepers who had been bought out by the fair and who repeatedly appeared before the Police Commission to demand a new license for a site near a fair gate. In so doing, the police and exposition board denied these business owners any opportunity to present their claims that they too deserved to make a profit from fair visitors.84

When fair officials closed the saloons, they remade the city into a place that catered to middle- and upper-class tourists and city residents rather than to the working class. Fair officials sought a city that would welcome middle- and upper-class tourists, for they were the consumers and potential settlers whom officials hoped to draw to the fair. When the desires of city residents—such as the saloon owners and their patrons—seemed to interfere with those plans, they found their goals thwarted by fair officials. Like other saloon owners, Schwartz believed that the clearest benefit the fair could bring to him was more business, and what better place was there to locate his business than across the street from the fairgrounds? He and other saloon keepers relocated by the exposition deeply resented fair officials’ beliefs that their institutions had no place in the “Exposition City” that the officials sought to create.

Fair officials put themselves at odds with another set of small businessmen when they attempted to regulate the city’s hotels and rooming houses. Pre-fair publicity promised visitors that “San Francisco is prepared today to take care of 100,000 visitors daily.”85 Such promises relied on the willingness of hotel owners and managers to clarify both their rates and policies for the exposition period. Other cities hosting large fairs and celebrations experienced outrageous hotel rates during the events, scaring away visitors. Such episodes “left bitter memories with many,” according to fair director Frank L. Brown, and he and other directors were determined that San Francisco not suffer the same fate.86

Exposition officials first worked with hotel owners on an informal basis by sponsoring the San Francisco Hotel Bureau. Members of this voluntary organization, founded in early 1914, agreed to publish their rates well in advance of the exposition and participated in a coordinated system for advertising and booking hotel rooms for visitors. Local hotel owners ran this group without exposition interference. Fair management supported the organization as long as it maintained a membership of the majority of the city’s hotels.87 The relationship between hotel owners and the exposition soon deteriorated, as a 1914 letter from Moore to the organization reveals. “That you should consider that you have a grievance against the exposition is surprising to me,” he charged, “because from our point of view we consider that we are the aggrieved party.” Moore maintained that hotel owners had never fully supported the fair. They failed to pledge an adequate amount of money to the original subscription drive and remained unwilling to cooperate with PPIE officials. Many hotels failed to publish their rates for 1915, creating bad press for the city, as “letters, reports, and newspaper clippings from various parts of the country” poured into the fair offices, “indicating the belief that visitors would be held up by the hotel interests here.” Now, Moore complained, the fair suffered from bad publicity about the hotel situation and the problem of having secured hundreds of conventions for 1915 with no assurance of reasonably priced hotels to house these visitors.88

Hotel owners already resented the exposition for having chosen to erect its own hotel, the Inside Inn, on the fairgrounds. They perceived this decision as a direct attack on their business and worried that PPIE publicity would direct visitors solely to the Inside Inn at the expense of their establishments. Would visitors be more likely to stay at the Inside Inn rather than at a hotel located in the heart of the city? These concerns troubled local hotel owners so they began to agitate publicly against the Inside Inn. They petitioned the city’s Board of Supervisors to disallow the construction of the inn and attempted to stop approval of the project.89 At one meeting of the San Francisco Hotel Association, members decided to monitor the construction of the Inside Inn carefully and see to it that “every section of the fire ordinances is enforced.” In addition, once construction began, “time will then be ripe for a protest from the hotel and retail store keepers against this totally unnecessary competition.”90 Hotel owners believed that the Inside Inn threatened their ability to profit from the increased business that the exposition would bring.

Fig. 25. The Inside Inn advertised widely, frustrating local hotel owners. (Official Guide.)

Moore, however, maintained that hotel owners had brought the situation on themselves. Only when “it became apparent that the hotels here, large and small, would not agree to make adequate arrangements for caring for the people coming to the numerous conventions and congresses to be held here,” he reminded hotel owners, was the concession approved. According to him, the Inside Inn was not a direct attack on local hotels but a last resort in the fair’s attempt to fulfill its “responsibility . . . to guarantee right treatment to visitors during their sojourn here” and, no doubt, to meet fair officials’ goals for its financial success.91 Moore saw no way to guarantee such treatment if hotels would not agree to publish their rates and to promise to abide by them during the fair. Moore and other officials were far more concerned about the prospect of bad publicity keeping visitors away from the fair than about the desires of hotel owners to profit from artificially higher rates.

Fair officials decided by late 1914 that the San Francisco Hotel Bureau was no longer adequate to the task. The PPIE created its own hotel bureau after determining that the old organization represented too few establishments and was “dominated by certain political influences.” The Official Exposition Hotel Bureau absorbed the original San Francisco Hotel Bureau in early January 1915. By early February, 133 local hotels belonged, and officials hoped that by opening day they would have a list of between 250 and 300 participating hotels, representing between 20,000 and 30,000 available rooms in the city. Although the bureau was part of the PPIE Division of Exploitation, a board of leading hotel men supervised it.92

The creation of the hotel bureau demonstrated PPIE officials’ willingness to borrow the progressive reform technique of using regulatory power to benefit the fair. In order to belong to the Official Exposition Hotel Bureau, a hotel owner had to submit the hotel’s rates to the board for the organization’s approval. Excessively high rates would not be accepted. Moreover, the bureau promised to distribute business evenly throughout member hotels, with only the patron’s preference affecting hotel choice. The exposition sold this plan to hotel owners by promising to advertise all hotels equally throughout the world, thus taking the burden of advertisement off of them, a particular boon for small hotels. The exposition did not provide this service free of charge, however; a hotel owner paid a dollar for each room in his or her establishment in order to join the bureau.93

The exposition’s takeover of the San Francisco Hotel Bureau apparently succeeded. It published an extensive list of available hotels, clearly showing their rates and the numbers of rooms available. Uniformed Official Exposition Hotel Bureau guides met every train and boat that approached the city and provided room information to visitors. The bureau offered free hotel reservations in advance. Or a visitor could locate a room simply by stopping by an Official Information Booth, which could be found at every terminal railway station, in downtown San Francisco, in downtown Oakland, and on the exposition grounds. The Universal Bus System would chauffeur anyone from any terminal station to any hotel for only twenty-five cents.94 A report from the summer of 1915 noted that “adverse newspaper criticisms regarding expected high hotel rates has almost ceased,” indicating that the fair’s advertising strategy was successful.95 And according to the bureau’s final report, it had not received a single “reasonable” complaint of overcharging or mistreatment.96 Moreover, San Francisco hotel owners had scored a victory in November 1914 when fair officials agreed to stop sending out pamphlets advertising the Inside Inn with all exposition correspondence and to circulate instead advertisements that included information about all hotels in the city.97

These conflicts between hotel owners and the exposition concerned both how much regulatory control the exposition should wield in the city and who should benefit from the event. Rather than the municipal government, a private corporation ran the fair, yet fair officials freely interfered in local business practices. This intrusion frustrated both saloon and hotel owners. On the one hand, local hotel owners joined the hotel bureau because they perceived the advantages of pooling resources to advertise nationwide, but they resented the exposition’s heavy-handed treatment of their business. They believed that the Inside Inn was an absolute betrayal of the fair’s promises to bring profits to the city. They had pledged to support the exposition because it would bring business to the city, and then the exposition erected a hotel that would directly compete with their business. What more evidence did they need that exposition officials were simply out for a profit? Exposition directors, on the other hand, believed hotel owners were deliberately obstructing their plans for a successful (profitable) fair, and they sought to institute regulations that would ensure fair rates for all visitors. Again, fair directors put their desires to make the fair financially successful above the desires of some city residents, unleashing the antagonism of those local residents.

Just who should benefit from the fair remained a thorny issue after the fair began. Fair officials, acutely aware of the need to make the fair profitable, repeatedly denied requests to lower ticket prices. This position frustrated many local residents. In March 1915, Mrs. C. H. McKenney of San Francisco wrote Mayor Rolph concerning her objection to the high admission prices to the exposition grounds. “I am writing this protest,” she told him, “as I think you are a just man, and would like the poor as well as the rich to enjoy the Exposition.”98 Rolph’s reply has been lost to history, but McKenney’s letter raised a persistent issue during the period leading up to and during exposition. To whom did the exposition belong? Should all San Franciscans enjoy the fair? Would its benefits (whether financial, educational, or cultural) be reserved for wealthy San Franciscans, visiting tourists, and fair officials?

Canny residents repeatedly attempted to “beat the gate” by climbing into the fair and directly challenging fair officials’ efforts to regulate access to the event. San Francisco Chronicle feature columnist Helen Dare revealed that fence climbers had become a problem when she devoted an entire Sunday column to “Beating—and NOT Beating—the Gate at the Exposition.” Her rather entertaining explanation of the many ways that visitors attempted to enter without paying failed to mention that this tactic reflected a very real class conflict. Some attempts to beat the gate came not out of an attempt to cheat the system but out of an inability to pay for entrance to the fair. She focused on society women who haughtily entered the gates and professed to have “left their pass at home,” only to have it revealed that they had no pass. Her mention of “a small army of men, women and children [who] broke through the Presidio gate to see the Vanderbilt Cup race” suggests that many people were frustrated enough by their lack of access to the grounds to resort to illegal means.99 The desires of these residents to see the fair overtook any concerns about breaking the law. While some wealthy women may have brazened their way through the gates simply to prove that they could, far more people likely fought to enter the fairgrounds because they thought that as city residents they should be able to enjoy the same entertainment as their wealthier neighbors.

These episodes remind us that despite assurances that the fair would bring the city together, working people of all races and both genders had a hard time coming up with the money to visit the fair more than a few times during its nine-month run. A working family with two children faced an admission cost of $1.50 simply to enter the grounds, without even purchasing a view of the “breathing” painting Stella or of the Panama Canal in the Joy Zone.100 Further, with the government exhibit palaces closed on Sundays, those who worked a six-day week might never have been able to visit those displays. Despite repeated pleas by visitors of all classes to reduce the children’s cost of admission to the fair, exposition officials refused to do so unilaterally. Instead they occasionally did so for school groups or other “deserving” groups of children. Although a limited number of discount passes costing $10 were available for sale before the fair, the demand far outpaced the supply. Even that pass’s one-time payment still was out of reach for many working-class people.

Fig. 26. PPIEA stockholder season ticket book, 1915. (Collection of the Oakland Museum of California.)

Fig. 27. Turnstiles at the Fillmore Street entrance. Exposition guards manned each entrance to the grounds. (#1959.087—ALB, 2:19, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

It could be quite difficult for working and middle-class families to find the money to fully enjoy the fair even after they entered the grounds. Annie Fader Haskell, a widowed schoolteacher whose diary revealed her enthusiasm for the PPIE, noted, “I guess I will not be able to see the side shows if it costs over a hundred dollars to see them.”101 When she was finally able to visit the fair in early May, she “had a nice, well served, reasonably priced dinner” on the Zone.102 Later that month she and her family “had to walk a long way back to get lunch. That is a mistake. We shall have to manage better next time. Maybe take a lunch or something.”103 Haskell thought very carefully about where she was going to eat on the grounds and what to purchase with her limited spending money.

Wealthier visitors, however, had no such dilemmas about how to spend their funds at the exposition. Mary Eugenia Pierce, a single Berkeley woman, enjoyed far more of the fair’s luxuries than did Haskell. Pierce’s first lengthy diary entry about the fair noted that she met her friend Mr. Poole at the ferry building, and they proceeded to the fair, where they ate dinner at the Inside Inn and took electric chairs for three hours in the evening to see the grounds.104 The chairs, or “electriquettes,” were wicker basket chairs on wheels propelled by a lead storage battery. At $1.00 per hour, they were a luxury for visitors. Pierce and Poole’s use of the chairs for three hours—at a total cost of $6.00—reveals her ability to take advantage of the more expensive attractions on the grounds.105 Four days later, the two friends met again and spent the day at the fair together, dining at the Old Faithful Inn for both lunch and dinner. Pierce, unlike Haskell, also ate out regularly while visiting the grounds.106

Pierce’s use of the fairgrounds reveals that wealthy local residents integrated the PPIE into their already active social world. Social clubs hosted dinners at the Inside Inn and the Old Faithful Inn while the Woman’s Board held regular dansants and teas in the California Building that were especially popular with the younger members of San Francisco’s high society.107 Upper-class San Franciscans visited the fair regularly. Clemens Max Richter, who lived quite near the grounds on Clay Street, noted in his autobiography, “Of course we visited the Exposition almost every day and we took the greatest delight in using the little auto-like vehicles for locomotion, or the miniature trains.”108

The fair was a quite different experience for working-class San Franciscans. Exposition directors did little to make the fair more accessible to lower-income San Franciscans. Although Moore avowed before the fair that “the Management feels it would be lacking in its duty if it did not do everything in its power to provide facilities whereby the people of San Francisco and the vicinity would derive the maximum benefit that can only be obtained by many visits to the Grounds,” he and the other directors consistently refused to consider additional plans to admit those who could not afford the fair.109 In October, the Executive Committee of the Board of Directors finally approved the issuance of twenty-five hundred passes for children and another twenty-five hundred passes for adults that would be dispensed by the Associated Charities, Catholic Humane Bureau, and Hebrew Board of Relief. The use of the reduced-rate passes, which cost a nickel for children and a quarter for adults, was closely regulated and restricted to the first and third Mondays and Fridays in October. Moreover, fair officials required that a member of the participating charities be present at the gate to identify each person who attempted to enter on a reduced-rate pass.110 This process, which certainly allowed some needy people to view the fair, failed to reach those working people who had no contact with such charities. Thousands of San Franciscans were not recipients of these charities, and they could not easily afford admission to the fair. The restrictions placed on the passes also complicated their use by those whose work lives made it difficult for them to find time, as well as money, to visit the fair.

Fig. 28. Electric roller chairs rented by the hour and used at the exposition. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

When working people voiced their concerns about the steep admission prices, they demonstrated their belief that the benefits of the exposition should extend to them. McKenney’s letter to Rolph provides insight into the situation. Her husband was a mechanic who earned $4.00 a day, and, she told Rolph, the price of admission meant that at the most they could only hope to visit the exposition once a month, or not nearly enough time to see “half of it.” They had gone on opening day and been “delighted with it all,” but they could not afford to visit as often as they would like. She hoped that the mayor could mention her concerns to the exposition management, for she assumed that he would understand.111 She, and many others, believed the fair boosters’ claims that it was truly a public event; thus she felt that they should, as citizens of San Francisco, be able to enjoy it just as the wealthy did.

Working-class San Franciscans and fair directors often had differing conceptions of the benefits that the PPIE should bring the city. Since fair directors put financial success as their top priority, the concerns of those residents who could not afford the fair were of little interest. To the frustration of some residents, then, despite avowals that the fair would belong to all San Franciscans, it very clearly did not. The cost of the fair proved an insurmountable barrier for some would-be visitors, while for others, like Haskell, who could afford the entry fee, it meant that the experience inside was less convenient than it could have been. Haskell never hired an electriquette, rested at the Inside Inn, or ate at the Old Faithful Inn, activities that Pierce took completely for granted in her fair experience. Working-class citizens attempted to lay claim to the fair by beating the gate, by protesting admission prices, and by skimping and saving to pay for the few visits they could afford, but the experience of visiting the fair fundamentally belonged to tourists and those San Franciscans who easily could afford the entry fee. Working-class San Franciscans more often experienced the fair as a worker rather than as a regular visitor. Despite Moore’s promise to make the benefits of the fair available to all San Franciscans, clearly neither the grounds nor the activities therein were ever available to all. It is thus difficult to conclude that the fair brought civic unity to all San Franciscans, since the fair directors’ emphasis on economic success meant that only the most privileged were able to enjoy its benefits fully.

San Franciscans of all stripes were involved in debates over the fair. They weighed in on the location of the site, the extension of municipal rail lines, the placement of saloons, and the regulation of hotels. Many believed the fair should truly serve all San Franciscans. Once the fair opened, they sought access to the fair in whatever ways they could. They wanted to see the wonders of the Joy Zone, the artwork of the Palace of Fine Arts, the gorgeous gardens and palaces, and the splendid celebrations hosted by foreign governments. Individual residents might have failed to affect fair directors’ decisions when it came to the fair’s site or the regulation of local businesses—profit was still at the root of the fair officials’ decisions—but residents were far more successful when they collectively claimed space for their communities on the grounds. Local and ethnic communities staged parades and pageants and hosted special days in honor of their ethnicity or homeland. Keeping powerful local ethnic and religious constituencies happy seemed essential at a fair funded primarily through local funds.