Claiming Their Place

Thousands of Bay Area residents swarmed onto the fairgrounds on June 10 to celebrate Alameda County Day. County citizens staged a lengthy parade to crown the day’s events, and it included two floats designed by members of the Oakland African American community.1 One held fifty black schoolchildren dressed in their Sunday best and excitedly waving to onlookers. These local African Americans participated in the parade because they wanted to demonstrate their pride in their community and their claims to equal citizenship. Two months later, fair visitors likely noticed the large number of young Chinese men and women milling about the fairgrounds, all attendees at Chinese Students’ Day, an event that drew hundreds of ethnically Chinese students. As a part of their celebration they sat together for a photograph commemorating the occasion; the impressive mass of young men and women were dressed mostly in contemporary Western attire: suits, ties, and long skirts.2 This photo stood in stark contrast to popular images of Chinese in the United States that depicted them as exotic (and often morally corrupt) others. These two episodes demonstrate one way in which the Panama Pacific International Exposition offered local ethnic communities a place to construct their group identities.

San Francisco’s ethnic, racial, and religious communities provided a broad base of support for the fair and took full advantage of the opportunities it presented to celebrate their heritage. Despite scholarly arguments that emphasize the exclusivity of the vision of the world presented at world’s fairs, these and other events demonstrate that the PPIE offered space for visions of a far more inclusive society.3 Many officially sanctioned exhibits at the fair celebrated American expansionism and the dominance of white Americans both at home and abroad, but that narrative never went unchallenged. From the young white and black boys holding hands as The Heroes of Tomorrow in the Nations of the West to the events described in the previous paragraph, the PPIE presented a contested vision of race and ethnicity.

Exposition directors maintained some control over exhibits, but they did not control all events on the grounds. Local residents celebrated their ethnic heritage, hometown, or county. Fraternal, political, and religious groups not only created parades, pageants, and speeches to assert their particular place in local society but also used the fair as a stage on which to declare and debate their place in American society. Members of local communities negotiated with fair directors and within their own communities about how they would participate in the event and about how they would be portrayed on the grounds. After the fair began, they actively inserted themselves into the vision of California created at the exposition. These attempts at times produced conflicts. The resolution of these conflicts and the resulting images of these sometimes-marginalized groups at the PPIE depended on their relationship with the city’s power structure and the exposition’s management, as well as on their relationship to the fair’s larger narrative about California’s history and society.

Local residents eagerly anticipated the coming of the PPIE. Real estate agents and business owners hoped the fair would work economic miracles, and local residents perceived possibilities for their own participation. The Bay Area’s cosmopolitan population provided a rich source of support for the PPIE. Fair officials eventually formed sixteen official auxiliary groups representing local ethnic communities. Prominent professional men formed the nucleus of these organizations. The most active factions included German Americans, British Americans, Finnish Americans, Swedish Americans, Italian Americans, and Dutch Americans.4 Fair officials called on these men to publicize the fair in diverse ways. They hosted events for visiting officials from their homelands, sent letters and telegrams to friends and relatives to convince them to support their nations’ participation in the fair, and raised money to stage events at the fair. Some members were asked to travel with official PPIE delegations abroad to visit their homelands. Such delegations went to Finland, Greece, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and Serbia. Not all were successful. Of those nations only Greece, Norway, Portugal, and Switzerland agreed to participate. But these activities demonstrate these men’s deep commitment to the success of the fair and the importance they attached to seeing their ancestral homelands represented therein.5

Fig. 29. Dedication of the Swedish Building at the PPIE. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Local members of these auxiliaries sometimes played a significant role in convincing foreign nations to participate. It was only the forceful persuasion of prominent local Norwegians that convinced Norway to send exhibits, and likewise enthusiastic Swedish San Franciscans convinced a reluctant Swedish government to erect a building at yet another exposition.6 As James Kaplan argues, the early twentieth century was a time of great rivalry between ethnic groups in cities, with events such as tug-of-war and drill team competitions providing venues for friendly contests between local groups. Therefore, local ethnic leaders perceived the PPIE as an opportunity to increase their prestige and to show off elements of their distinct culture and history. For Swedes, he argues, it was a way for the urban professionals of the Bay Area to differentiate themselves from popular stereotypes that depicted Swedes as taciturn midwestern farmers.7

Fair officials may have seen the involvement of local ethnic groups as a way to drum up support and funds for the exposition at home and abroad, but local groups perceived their work in other ways. Local Welsh residents organized a huge eisteddfod—a traditional celebration of Welsh music and poetry dating to medieval times—for the fair, because they believed it would be in the “best interest of the Welsh people” to preserve and perpetuate its “traditions, literature, music, customs and language.”8 Given that letters poured into the exposition office from the idea’s supporters in both the United States and Wales, exposition officials no doubt perceived the value of linking the eisteddfod to the fair as another means of drawing visitors rather than as a way of affirming Welsh heritage. In another example, upon the dedication of the fair’s Swedish Pavilion, the local Swedish paper reported that there was no one in the crowd who “did not feel the indescribable joy of having the privilege of being Swedish.”9 The PPIE offered a remarkable opportunity for ethnic communities to affirm their own ethnic identity and to proclaim it to others.

The German community’s efforts to bring Germany to the fair illustrated the effort that ethnic groups put into organizing a presence at the exposition, even when faced with their homeland’s failure to participate. Their activities became deeply entwined with national political debates. German Americans organized early to try to urge the participation of their ancestral homeland. The head of the German-American Auxiliary, Edward Delger, even traveled across the United States, stopping at cities with large German populations as he attempted to drum up support for the PPIE.10 Despite the enthusiasm of local Germans, the German government resisted the fair officials’ overtures and declined their invitation to participate. Sources cited frustration with the large number of previous expositions recently held in Europe, as well as a sense that the expense associated with staging an “appropriate” exhibit for Germany was simply not justified.11 After Germany chose not to participate, the German-American Auxiliary mounted a campaign to build a Palace of German-American History and Culture, soliciting funds from Germans around the United States. The beginning of World War I frustrated that plan. In July 1914 the auxiliary formally gave up its site on the grounds, admitting it would be unable to stage a German exhibit at the PPIE.12 The official report explained that the war caused German Americans to divert their “pecuniary sacrifices” to the “relief of the wounded, widows and orphans of the Fatherland.”13 Nonetheless, the group managed to stage a weeklong celebration during German Week at the fair and arranged for a New York Beethoven choir to donate a Ludwig van Beethoven monument in Golden Gate Park as a permanent tribute to the members’ German heritage.14

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the celebration of German Day on August 5 would include “no floats and no military display, the idea being to represent merely the numbers and loyalty of the Germans in this country.” Subsequent reports about the day’s events reveal a more complicated story.15 The parade included thirty-five thousand participants, including a group of “Irish Volunteers” bearing the Irish flag and a group of German military veterans marching in goose step. One headline informed readers that the “Exposition is captured by German-Americans,” and the accompanying story contained multiple references to war and military strategy, making it hard to believe that the writer was not intending to link this celebration of German Americanness to the ongoing war in Europe.16 Reports in other newspapers across the country, including the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and the Decatur (Illinois) Review, added a detail that was missing from the Chronicle’s account. Upon being informed that Warsaw had fallen to the Germans, the assembled crowd “went wild” cheering Germany’s victory.17

Keynote speaker, Dr. C. J. Hexamer, president of the German-American Alliance, gave a public speech in which he focused primarily on German contributions to American culture, but he also insisted on the importance of preserving their “Germanness” and decried the move toward “hyphenated” Americans.18 Such rhetoric avoided the war, but the concurrent meetings of the German-American Alliance squarely addressed the grievances of German Americans. Newspapers reported in great detail about the debate that ensued over a proposed “hot” letter to President Woodrow Wilson that heavily criticized his administration’s policy toward Germany and the war. The membership failed to approve the letter after members of the elected leadership threatened to resign; instead, it adopted a milder but still critical resolution that focused mainly on decrying the U.S. policy of selling arms to the Allies, a practice that the group perceived as a violation of neutrality.19 Other resolutions adopted during the sessions criticized eastern newspapers for their allegedly pro-British bias and opposed increasingly strict immigration laws and the curtailing of civil liberties at home.20

Fig. 30. German Day at the PPIE. (#1996.003—ALB, 3:131, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

German Week at the fair brought the national discussion about the relationship of German Americans to the United States and Germany to the fore. Although the United States would not enter the war for another twenty months, tensions between supporters of Britain and Germany were already building, and after the United States entered the war, they would flare up into explicit anti-German discrimination and violence. At the PPIE, German Americans attempted to negotiate these frictions. They asserted themselves both as U.S. citizens with the right to criticize their government’s actions and as loyal children of the German fatherland.

The majority of local communities involved in the exposition seem to have experienced little or no conflict with the fair. Although some officials might have quibbled about budgets or appointments, no records remain of strains with most of these organizations. Some local groups, however, did experience major debates regarding their participation in the fair. It is to those issues that we now turn, for they demonstrate the significance that local communities placed on the fair and the ways that the Bay Area’s local political and social cultures shaped the vision of society that greeted fair visitors.

San Francisco’s social structure affected the ability of ethnic groups to determine their representation on the fairgrounds. The popularity of The American Pioneer and The End of the Trail sculptures and the ’49 Camp attraction in the Joy Zone remind us that the Panama-Pacific International Exposition celebrated American expansionism and the conquest of the West. This story, reproduced in postcards, souvenirs, and in the statuary of the fair, mirrored the fair’s larger messages about the superiority of mainstream white American culture. Scholars debate precisely who qualified as “white” in the early twentieth century, however, recognizing the ways in which southern and eastern Europeans and Jews were often racialized as nonwhite others. Debates over immigration restriction in the 1910s focused on eliminating the presence of these supposedly inferior peoples. In the nineteenth century, Irish immigrants had faced similar prejudices, and a long history of anti-Catholicism plagued U.S. society. Irish, Roman Catholics, Chinese, and African Americans each faced discrimination in other parts of the country, but their status in San Francisco did not always reflect their marginalization in other parts of the nation. Their ability to make change on the fairgrounds was intimately connected to their status within the city.

San Francisco’s Gold Rush history created a religiously and ethnically diverse social and cultural establishment. Jews, Catholics, and Protestants lived relatively harmoniously in the city, with all three groups wielding significant cultural, political, and economic power. As historian James P. Walsh notes, “In San Francisco during the 1850s, everyone was uprooted, Americans and foreigners alike. The Irish, however, enjoyed the distinct advantage of having had experiences in that condition. . . . San Francisco lacked an entrenched establishment. . . . The Irish were not easily shouldered aside in the competitive scramble for the good things this new society offered.”21 This assessment also applied to the opportunities available to other ethnic and religious groups and accurately reflects the social structure of the city’s early history.

The most powerful Catholics in San Francisco were Irish and vice versa, but the city also had a large number of German Catholics and increasing numbers of Italians. The Latino population of the city was quite small in the early twentieth century and did not represent a power bloc within the church or the city.22 Similarly, most Italian immigrants were more recent arrivals in the city and, as a group, did not yet wield the same kind of power as the more established Irish and German Catholics. Irish immigrants began to gain power in the city during the Gold Rush. By the time of the PPIE, the Irish composed a majority of the Catholic population in the city, and the Catholic Church claimed a majority of churchgoers. Of the six archbishops who held the office between 1853 and 1985, five were Irish.23 Irish Catholic union men ran the powerful Building Trades Council (BTC) and sat on the San Francisco Labor Council (SFLC). Recent San Francisco mayors had been both Irish and Catholic. The dominance of the Irish in the Catholic Church was so extensive that new immigrant groups were shunted off into new “national” parishes rather than being integrated into existing Irish ones. The Irish and Italians had a particularly troubled relationship in the city, although it had improved by the time of the fair.24 Prominent Irish Catholics actively assisted in planning the exposition and used the exposition to represent both their ethnic heritage and their faith to fairgoers.

Racial intolerance in San Francisco primarily targeted Asians, who were marked as permanent aliens in San Francisco society. As with thousands of others in the 1850s, the Chinese were drawn to the California gold fields but later moved from mining to the wage labor force, and they were often willing to work for lower wages than their counterparts were. By the 1870s, labor unions and those who feared the invasion of an alien workforce willing to work for low wages stoked anti-Chinese sentiment, which gained strength in the West. Racist propaganda depicted the Chinese as opium addicts and gamblers and their settlements as dens of vice.25 Violent attacks against the Chinese occurred across the West, culminating in the federal 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred the entry of Chinese laborers to the United States. Despite this racist opposition, Chinese immigrants created a community for themselves in the city of San Francisco, and Chinatown remained home to the largest concentration of Chinese Americans in the nation.26 Since the turn of the century anti-Asian sentiment had primarily targeted the Japanese, but the Chinese remained racialized as permanently outside the American body politic. Economically, however, the Chinese were a key part of San Francisco life. The decision to add traditional Chinese architectural details to the neighborhood during the post-earthquake rebuilding helped to make Chinatown a popular tourist attraction and a key part of the city’s skyline.27 As wealthy Chinese merchants wielded economic power in the city and white businessmen sought good relations with Chinese merchants both at home and in China, the coming of the exposition offered the local Chinese an opportunity to assert themselves in multiple ways. In the eyes of some non-Asian spectators, however, the Chinese remained racially and morally suspect.

Few African Americans lived in San Francisco, making their social position more tenuous than that of the Chinese.28 Black San Franciscans experienced a difficult labor market. The vast majority of black women worked as domestics, and black men also worked menial jobs.29 This occupational segregation suggests that many white San Franciscans felt an antipathy toward blacks, as well as a reluctance to work alongside them. When labor leader C. L. Dellums migrated to the Bay Area in the early 1920s, for instance, the train porter told him, “Let me give you some advice, young man. Get off in Oakland. There are not enough Negroes in San Francisco for you to find in order to make some connections over there.”30 African American activist W. E. B. Du Bois blamed this phenomenon partly on the strength of the city’s labor unions, some of which deliberately excluded blacks.31 Overt discrimination existed in the Bay Area as well, even if it was not legally sanctioned. Cheap restaurants sometimes carried “whites only” signs.32 The same negative images of blacks that appeared in other parts of the country certainly also appeared in San Francisco. The film Birth of a Nation opened in early 1915 to great success in the city and was welcomed back for a second run in April.33 African Americans, like the Chinese but unlike the Irish or Catholics, faced significant negative stereotypes both on and off the fairgrounds.34

As the Welsh and Swedish enthusiasm for the fair reveals, many San Franciscans seized the opportunity to celebrate their ethnic heritage at the PPIE. Local communities took the chance to stake a claim in U.S. society and to present themselves to the public in the way that they, rather than publicists or the media, chose. The fair’s dependence on local monies meant that fair directors tread carefully with many of these groups, wanting to preserve relations with powerful local interest groups and valuable foreign partners. Pre-fair negotiations, both in and outside the Chinese, African American, and Irish communities, demonstrated their relative power in the city and the opportunities that the fair opened up for them.

Local Chinese hoped the fair could improve the status of Chinese Americans in California and boost China’s worldwide reputation. The founding of the Republic of China in 1912 stimulated nationalist sentiment among Chinese overseas, and they were eager to support China’s efforts to prove itself a strong nation. The editor of the San Francisco paper Young China urged, “At the Panama Exposition, we must devote all our energy to it so that Americans will know the reality of our national power.”35 The local Chinese Western Daily emphasized how important the fair could be to the development of China, since Chinese overseas could learn much to “push forward Chinese culture and civilization.”36 Others urged that city residents seize the chance to improve Chinatown’s image and status both by cleaning up Chinatown so as to impress visitors with “Chinatown’s fame” and by raising funds for electric lighting in the neighborhood to make it on par with “Western” neighborhoods.37

Members of the local Chinese community remained unsure about the exposition and of their role in it. Many Chinese merchants pledged generously to support the exposition in the early fund-raising drives, but that enthusiasm waned as the fair approached. The proposal of a harsh immigration bill, the debates over California’s 1913 Alien Land Law, and a series of issues about the importation of Chinese exposition laborers complicated relations between Chinese residents and the fair’s organizers. By early 1914, local attorney John McNab reported to Charles Moore, “The Chinese people feel that they are being called upon to assist a Government Exposition, while at the same time, they are as they see it, being unduly harassed by a Government with which they are friendly.” This harassment included crackdowns on activities in Chinatown and changes in immigration procedures that made it more difficult for resident merchants to return to the state from abroad. These activities soured members of the Chinese community on financially supporting a fair sponsored by a state that persisted in discriminating against them and challenged exposition officials’ attempts to solicit local Chinese support of the event.38

Fair officials responded to this skepticism by courting prominent local members of the Chinese community. The exposition established an official “Chinese Committee” to hold a series of meetings with representatives of the Chinese community and to iron out their concerns.39 Fair officials organized outings and tours of the fairgrounds to impress prominent local Chinese merchants and bankers. PPIE lawyers attempted to convince them that the fair management “should not be held responsible for governmental immigration laws.”40 They hoped these efforts would both convince Chinese community members of the splendor of the fair and help to distance the fair from federal immigration laws.

Like the Chinese, Irish San Franciscans feared what images of their homeland might appear at the exposition. Earlier expositions had included Irish villages on their midways that presented negative stereotypes of the Irish. Although less anti-Irish sentiment existed in San Francisco than in other parts of the country, the San Francisco Irish remained concerned that the fair might include exhibits that would portray them as outsiders to American society rather than as valuable citizens. Those who supported Irish independence from Great Britain, meanwhile, hoped the fair might offer a space in which to assert that goal to an international audience.

Prominent local Irish residents formed the Celtic Society of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition to meet with fair directors and discuss Irish participation in the fair.41 They wanted the fair to solicit an independent Irish exhibit, even though Ireland was still a part of Great Britain.42 This full exhibit would highlight Ireland’s commercial and manufacturing interests and “show the world that in every department of human endeavor Ireland . . . can stand with the best.”43 These men hoped that highlighting Ireland’s economic success would dispel the visions of a preindustrial, backward nation that still circulated in parts of the United States. To their disappointment, the plan failed. Irish representatives declined to send an official exhibit to the fair, probably because participating in an international exposition during wartime became impossible.

In stark contrast to their active courting of local Chinese and Irish leaders, fair officials more often rebuffed and ignored African Americans when they attempted to contact fair officials. Prominent black leaders tried to approach exposition officials in the planning stages of the fair, but no evidence exists to suggest that they had any success.44 As early as 1911, black Californians petitioned PPIE officials to organize a display featuring African American achievements but to no avail.45 The only corroboration of a discussion between the fair organizers and black leaders is a letter from W. E. B. Du Bois, in which he refers to discussions held in 1913 with fair officials who decided that “a special Negro department was unwise.” In 1914, he proposed the staging of an impressive pageant and celebration of black culture and history to music director George W. Stewart, but no evidence exists as to whether Du Bois pursued it after Stewart told him it was out of his purview.46

Nor did the fair bring many jobs to the black community. S. L. Mash, the president of the Colored Non-Partisan League of California, wrote to Moore in 1915 to complain that his investigation into the job situation for blacks had solicited a response by fair officials that “no Colored Man or Colored Help would be employed in certain positions and departments in the Panama Exposition.” Mash argued that this policy would certainly bring the wrath of eastern blacks upon the exposition. Many black churches and organizations nationwide had staunchly backed San Francisco as the choice for the site over segregated New Orleans in the belief that discrimination would not be practiced in California. He pointed out that such exclusionary practices would betray this trust.47

Secretary Rudolph Taussig reassured Mash three weeks later that the fair would not do anything “so un-American.” In fact, “there are quite a number of colored men employed in the buildings and on the Grounds,” he informed him. He did admit that the fair had not hired any black guards since the force had “been made up mostly of veterans of the Spanish war, and were our force large enough, no doubt we would consider forming a colored company.” Including blacks at that time remained out of the question. Taussig did not directly answer Mash’s charge about the discrimination in “certain” departments.48

A private memo from James S. Tobin, exposition director and lawyer, to Moore about the situation revealed much about the fair officials’ attitude toward the conflict. “I think a few tactful words will quiet the fears of these ‘wards of the nation,’” he wrote.49 This patronizing attitude suggests that neither Tobin nor Moore intended to take any actions to alter the fair’s racial policies. His phrase “wards of the nation” shows that he perceived African Americans as less than full citizens of the United States. The term reflected decades of post–Civil War debate on the readiness of blacks to assume the economic and political rights of full citizenship. It was one used by those who sought to infantilize and patronize African Americans rather than include them in the body politic. The Oakland Sunshine, a local black paper, reported at the end of the fair, “The Negro . . . derived but very little benefit [from the fair] outside of a few minor jobs as maids and helpers.”50 Many black employees on the grounds worked as restroom attendants or janitors, positions that did little to further their economic or social status in the city.

Some in the black community continued to support the event despite their exclusion from the planning process. They saw the fair as a space from which to voice their civic pride and to assert their citizenship. To this end, they worked to accommodate African American visitors. The Western Outlook voiced concern in January 1915 about whether the community was ready to “recognize our full responsibility towards those of our race who come here and who expect to find accommodations that will prove satisfactory and who will not be victims of discrimination.” The writer argued, “If there is any mistake in the beginning, and the officials of the exposition are not able to fulfill promises . . . it will be a big loss to them,” keeping many visitors away from California.51 Such discrimination would hurt not only the exposition but also the black community in the Bay Area.

A group of prominent Oakland blacks met soon after to discuss establishing a hotel bureau to meet the needs of visiting African Americans. They resolved to cooperate with local civic and fraternal organizations to create such a bureau.52 A few weeks later, a group of black women in San Francisco sponsored the creation of a downtown Central Bureau of Information for Colored People to facilitate “the comfort and well-being of strangers who may chance to come among us and who care for the good name and reputation of our city.”53 In a similar, and perhaps competing, vein W. A. Butler of San Francisco established a “general information and room-renting agency” specifically designed to meet the needs of fairgoers.54 No evidence exists to explain the relationship between these agencies or how long they functioned. Their establishment does demonstrate that many blacks perceived a pressing need to better accommodate visiting African Americans. Some local blacks hoped the exposition would draw a significant number of visiting African Americans to the city and distrusted the dedication of exposition officials to provide for them.

The three distinct ethnic communities—Chinese, Irish, and African American—each perceived the fair as a significant place from which to claim space to assert their political and social goals. So, too, did Catholic San Franciscans. Once the fair began, conflicts emerged over the representation of each of these groups on the fairgrounds, and their resolution demonstrated the local power of each group. The groups sought to use the fair to claim space within the city, and their ability to do so rested on their place in the city’s social hierarchy.

Although fair officials attempted to maintain good relations with the local Chinese community, many Chinese residents remained skeptical. Yong Chen argues that the Chinese San Franciscans were embarrassed rather than proud of China’s attempts to present a modern face to the world. As we will see, debates in the years before the fair about the status of those Chinese workers who had been brought to build the nation’s pavilion highlighted the second-class legal status of Chinese immigrants in California. Moreover, Chen argues, when the Chinese government provided these workers with dirty quarters and ragged clothes, the immigrant community’s embarrassment only increased. The Chinese government seemed insensitive to the need to present a dignified appearance to curious white Americans. To add insult to injury, on the fair’s opening day, the main Chinese palaces remained closed. The only open teahouses served Japanese tea cakes, a situation that reemphasized China’s inability to present itself effectively to the world.55 The Chinese Western Daily angrily stated that the only Chinese features in the teahouses were “the clothes that the waitresses wear and the yellowish faces of the manager and cashiers.”56 It also published numerous articles over the next few months detailing the ineptitudes of the Chinese Commission and those charged with organizing the Chinese exhibits.

Unfortunately for Bay Area Chinese residents, the vision of China that greeted visitors at the fair included not only the half-finished Chinese national exhibit but also the far more disturbing Underground Chinatown. Many attractions on the Zone displayed nonwhite peoples in their so-called traditional villages. Underground Chinatown ostensibly represented Chinese life in the United States by plunging visitors into a re-creation of the supposed underground warrens of San Francisco’s Chinatown, where prostitutes and opium dealers and addicts plied their trade. Although such a place existed only in the white imagination, stories of an underground Chinatown circulated widely in nineteenth- and twentieth-century San Francisco. A contemporary report described one portion of the attraction: “A maudlin and degrading scene is enacted by a white man who knocks upon a door in company with a white woman and seeks admission to an opium smoking den within which is secreted an imaginary Chinese who demands to know if policemen are present. . . . When Chinese are not present among the visitors the slave-girl drama is enacted and a revolting scene in which women are inducted into slavery is made clear to the crowd.”57 The concessionaires included every possible nightmare about the Chinese and every contemporary social concern in the attraction. It played upon the history of the forced prostitution of Chinese immigrant women that had convinced many white Americans that all Chinese women were prostitutes.58 It also drew on Progressive Era fears of white slavery that associated California’s white slavers with Asian immigrants.59

Fig. 31. View of the Zone at the PPIE showing Underground Chinatown at the Chinese Village. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

Members of the Chinese community immediately voiced their displeasure with the demeaning attraction. Their language revealed their hopes for the fair. The Chinese Six Companies appealed to Moore “to end this outrageous travesty of the Chinese people.”60 They voiced their frustration about this concession, which drew the racial line between whites and the Chinese more strongly rather than easing it. Only a well-organized letter-writing campaign, however, forced the exposition into action.61 In mid-March, Chinese merchants, ministers, and student leaders, as well as white missionaries who worked in Chinatown, all wrote to Moore deploring the Underground Chinatown. They argued that the attraction portrayed a false image of the Chinese and did a serious injustice to a valuable segment of the San Francisco community. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce argued that “the law abiding, peace loving Chinese who in every manner have endeavored to assist the Panama Pacific International Exposition and whose untiring effort . . . brought to you a Chinese Republic exhibit, are disregarded, disgraced, and should this exhibition continue our people will feel they have misplaced their confidence in you gentlemen and in the people of this country.”62 A group of white Protestant mission workers objected to “the gratuitous affront to the best classes of the Chinese community, many of whom are among the most upright and law-abiding of any residents who have come to us from other lands.”63

The tenor of these complaints reveal that local Chinese residents recognized the power of the fair and of the Underground Chinatown concession to mark them as racial others who threatened white Americans’ moral standards. It confirmed their fears that the exposition would strengthen anti-Chinese sentiment. They resented the perpetuation of old stereotypes of San Francisco’s Chinatown in an event that was supposed to showcase the city. A group of Chinese ministers and elders noted, “The exhibitions [sic] . . . are deliberate falsehood, libel and slander and a disgrace to the Chinese race, for they are sheer fabrication from the imagination of the promoters . . . in order to make some dirty profit.”64 They pointed out that the conception of an Underground Chinatown originated years earlier when white guides led visitors interested in slumming into a fabricated vision of an Underground Chinatown that lay beneath the city. “We fought hard against this libelous concoction defaming our good name before the Police Department,” noted representatives of the Chinese press. “At that time the police stood by these guides, evidently sharing with them the evil gains.”65 The Chinese community resented that old falsehoods continued to be propagated to an international audience, when they had hoped instead to use the fair to improve China’s and Chinatown’s reputations.

Moore and the fair board responded only after Chen Chi, the official Chinese PPIE commissioner, stated in stark terms his government’s displeasure with the attraction and with the exposition’s failure to address the complaint he had lodged after the concession opened three weeks before. “Is it fair,” he asked Moore, “to our many law-abiding and moral Chinese residents that these unwise deeds and acts of perchance some immoral Chinese resident should be flaunted before the world?” China came to the exposition with the expectation that it would be welcomed as a friend, he argued, and “every country has a right to be judged not by the lowest elements of degeneracy in its past civilization but by its nobler attempts to develop the best that is in its peoples’ ambitions.”66 Despite Chen’s forceful objections and the censure of the Chinese government, the PPIE Committee on Concessions and Admissions closed the concession only under direct orders from Moore, who apparently realized the damage the attraction could do to the exposition’s (and the state’s) relationship with China.67

The concession reopened as Underground Slumming in June. Fair officials reassured the concerned Chinese community that it had dispensed with all offensive features. Although a San Francisco Chronicle article reported that the new attraction was “completely changed,” refocused on the evils of the drug habit and with “nearly a mile of underground passages, wherein are over 100 figures, showing the destroying effects of various prohibited drugs,” it remained closely associated with Chinatown.68 An ad placed in the San Francisco Call revealed this connection. It read: “On the Zone Underground Slumming Formerly Underground Chinatown More Impressive than any Play Book or Sermon.”69 The ad used a number of cues to inform readers that the attraction was still really about the Chinese. Changing “Chinatown” to “Slumming” did not remove the association with the Chinese, since slumming was the term for the popular practice of white men and women visiting Chinatown in search of a salacious view of the lifestyle they believed existed there.70 The reference to “any Play Book or Sermon” on the surface reassured potential visitors that it was an educational exhibit, but it also attracted those eager to see rather than simply hear about the evils of slumming and, by insinuation, Chinatown. Viewing the effects of the drug habit had an appeal that no play, book, or sermon could ever provide.

Both Underground Slumming and Underground Chinatown reinforced the racialization of the Chinese as exotic, corrupt others. In California, where Asians, rather than African Americans, were often most actively discriminated against, these images of corrupt, violent, and overly sexual Chinese held great power. In reopening the attraction, the concessionaire (and exposition officials) reinforced the association with Underground Chinatown by including both names in the advertising. The concessionaire hoped that visitors who might have missed the original incarnation might be induced to try the new version, despite the change in its name.

Underground Chinatown revealed that the local Chinese community was correct to be wary of the exposition. Rather than affirming Chinese immigrants as valued members of the San Francisco community and sons and daughters of modernized China, the Zone construed the Chinese as deviant, exotic others. Although Chinese San Franciscans succeeded in closing the original attraction, as long as Underground Slumming existed on the Zone it provided a powerful foil to the official Chinese exhibit on the grounds. To visitors familiar with visions of opium-addicted Chinese prostitutes and gamblers, the new attraction offered affirmation that the official Chinese Pavilion and Chinese-sponsored events would be hard pressed to counteract.

Local Irish Americans became involved in a discussion over representation of their homeland at the fair as well, but the matter was resolved rather differently. Although the Celtic Committee campaigned to bring an official Irish exhibit to San Francisco, the only Irish exhibit at the PPIE was the Irish Village on the Zone, the Shamrock Isle. The concessionaires who funded Shamrock Isle solicited support both in Ireland and in San Francisco. The exposition directors made an effort to gain approval from prominent Irishmen in San Francisco before accepting the application for the Shamrock Isle. In June 1913, the Committee on Concessions and Admissions unanimously passed a resolution requiring that “satisfactory reports in the form of letters be obtained from Mr. Mullally, Mr. Joseph B. Tobin, Father Jos. McQuaid, and Arch-Bishop Riordan”—all prominent San Francisco Irish Catholics—about the quality of the exhibit.71 The committee feared the disapproval of the Irish community enough to ensure that the display would be unobjectionable before issuing a contract.

Fig. 32. Irish Village in the Zone at the PPIE. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

The proposed attraction remained controversial despite this gesture toward the Irish community. Radical labor leader Father Peter Yorke, the editor of the Leader, the weekly Irish Catholic paper in San Francisco, warned that those behind the concession were planning something “on the same level as the concession for the Hairy Hottentots or the Blubbery Esquimaux” and on par with “the miserable exhibitions made at Chicago and St.Louis.”72 Yet the Monitor, the pro-Irish paper of the Catholic archdiocese of San Francisco, published an extensive interview with Michael O’Sullivan, the manager of the proposed concession, in which the exhibit was described in only positive terms. The village he described featured “an array of enormous old castles, round towers and ivy-covered ruins . . . a row of characteristic cottages of various sizes and colors, each on a picture itself, . . . a sturdy Irish boy with his immortalized low-back car of song and story. . . . And behind him, two rosy-cheeked, colleens come riding merrily along in a donkey cart.”73 This concession replaced one caricature of Ireland with another. It drew on a heavily romanticized vision of the Ireland that reduced Irish citizens to inhabitants of magnificent castles or charming cottages and obscured the reality of Irish struggles with industrialization and poverty. For those who hoped to have an official Irish exhibit that would highlight Ireland’s modernity and economic success, these plans for the Shamrock Isle must certainly have been a disappointment.

Yorke continued to criticize plans for the Shamrock Isle in 1914, but by 1915, discussions ended. Only periodic ads for the concession and general descriptions of fair attractions mentioned Shamrock Isle, suggesting that its depiction of Irish life may have been less damaging than was first feared.74 Since Yorke loudly voiced his original complaints, it seems unlikely he would have avoided criticizing the exhibit had it been as objectionable as he first assumed. The Shamrock Isle closed a few months after opening, suggesting that the image of Ireland it presented did not appeal to visitors in the same way that Underground Chinatown or Underground Slumming did. Fair historian Frank Morton Todd remarked that “the public did not seem especially interested in Irish singing and clog dancing—at least not enough of the public to make it pay.”75 Todd’s offhand note suggests why the Shamrock Isle never generated the same sort of attention—positive or negative—as Underground Chinatown did. The image it presented of Ireland did not carry the salacious interest, or the racial power, of the Underground attractions. Todd also reported that Underground Slumming drew many visitors, suggesting that viewers chose to spend their money on that attraction rather than on the Shamrock Isle or other Zone concessions. Visitors to San Francisco were more eager to see contemporary concerns about drugs and sex acted out in a racialized context rather than watching charming Irish lasses milk cows.

The local Irish remained vigilant about the depiction of their homeland at the fair. The editor of the Monitor complained in July that Alexander Stirling Calder had excluded the Irish from Nations of the West. As noted previously, this prominent statuary group stood atop one of the arches in the Court of the Universe and depicted the peoples who had shaped the United States. The editor charged that the piece ignored the Irish, who had been instrumental in building the nation.76 In response, Calder himself informed the paper that the Anglo-Saxon figure was intended to be “one collective representative of the whole British idea,” which included the Irish. Moreover, he claimed that Celtic ideals inspired his composition of the Mother of Tomorrow. Calder’s reply did not appease the Monitor, which termed it “alas, very lame.”77 The matter ended there, but the point was made. The San Francisco Irish, backed by the Catholic Church (as publishers of the paper), demanded representation on the grounds.

The complaint about Nations of the West seems trivial, but it demonstrates the power of Irish Catholics in San Francisco. Exposition officials worried enough about offending the archdiocese and the Irish community that it forwarded a complaint about a prominent piece of art on the grounds to the chief sculptor himself, presumably with a request that he address it. Their attempt to ensure that the Shamrock Isle proved inoffensive indicated a desire not to antagonize powerful members of San Francisco society. Exposition officials needed the financial support of the local Irish community. They would not risk affronting either the archdiocese, led by Irishman archbishop Edward Hanna, or the BTC, which was controlled by the Irish former mayor and exposition director Patrick H. McCarthy.78

Pleasing local Catholics, however, put the fair directors at risk of attack by the increasingly vocal anti-Catholic bloc in other parts of the nation. Nationwide, in the 1910s anti-Catholic papers focused on denouncing the “Catholics’ perceived inability to embrace American civic virtues—insisting that their adherence to priestly hierarchies make Catholics unable to accept American values of egalitarianism, individualism, and tolerance.”79 In the summer of 1913, rumors circulated among Protestant groups that a model of the Vatican would appear at the exposition. National protest erupted, as Protestants across the country voiced their concerns to Moore. One Missourian promised Moore: “Protestants in these parts are going to boycott the Expo. . . . You Catholic fellows think you are smart but you can’t fool us any longer. Every member of the Panama Exposition is a Jesuit.”80 Despite assurances that no such plan existed, religious issues continued to plague fair directors.

These tensions came to a head in the spring of 1914, when the Italian government announced the appointment of Ernesto Nathan, the mayor of Rome, as Italian commissioner to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Catholics, first in San Francisco and then across the nation, loudly protested his appointment. Nathan, an Italian Jew born in Great Britain, was a central figure in perpetuating the ideals of “Liberal Italy,” the term used for the secular Italian state founded in 1860. He condemned the Vatican as a backward remnant of a dying civilization and dismissed papal infallibility while he served as mayor of Rome. He maintained that modern Rome was “the champion of liberty of thought” while papal Rome was “the fortress of dogma where the last despairing effort is being made to keep up the reign of ignorance.”81 International protest against Nathan continued throughout his tenure as mayor, with many American papers and clergy weighing in.82 American Catholics who recognized the supreme authority of the pope and who viewed liberal Italy as an illegal state saw Nathan’s official presence at the exposition as an unspeakable affront to their faith.83

Catholics in San Francisco drew on their brethren nationwide to mount a loud and vigorous campaign to keep Nathan away from the exposition. The Monitor sounded the call in February by stating:

Against such an appointment not only every Catholic in the United States, but every decent citizen of our country . . . must and will protest. . . . He is not only the avowed enemy of Christianity, but the world’s arch-insulter of the Catholic Church. . . . Nathan is an English-born Jew and a violent Freemason of the most malignant European type. . . . All decent men of the Hebrew race repudiate him. . . . Let the Catholics of this city unite in one voice to protest against the coming of Nathan to San Francisco. Let them call upon their fair-minded non-Catholic brethren to join them in that protest.84

Letters from Catholics across the country poured into the exposition’s offices. The State Federation of German Catholic Societies of the State of New Jersey wrote in a March letter that its members “feel that a grievous insult has been offered the Catholics of the United States . . . by the Italian government” by appointing Nathan.85 The Monitor and the Leader continued to attack Nathan, blasting his reputation and reminding readers of the support the campaign was drawing from Catholics across the nation and world.

The debate over Nathan represented a constellation of social concerns about Catholicism, Freemasonry, anti-Semitism, the Italian state, and modernity in general. Anti-Catholic rhetoric came from devout Protestants and from anarchists and socialists who remained skeptical of any religion. Nathan’s Jewish heritage only complicated the issue, with some of the attacks drawing on traditional anti-Semitic rhetorical tropes. Although the Leader featured a headline that screamed, “Specific Bigoted Acts of Nathan, Cockney Jew,” the text did not dwell on his heritage other than to call him a “low type of Cockney.” Other editors were not so generous. The Western Catholic of Springfield, Illinois, “castigated Nathan, ‘the little Jew Mayor of Rome,’ whose ancestors, ‘hounded Jesus Christ to the darksome and bloody heights of Calvary.’”86 San Francisco papers tended to shy away from this virulent rhetoric, but most objections noted his Jewish heritage. Anti-Semitism remained just beneath the surface of the Catholic press’ editorials on the subject as well. The respect accorded to San Francisco’s powerful Jewish community likely mediated the issue.87 San Francisco witnessed little public anti-Semitism in the early twentieth century, demonstrating the city’s religiously tolerant culture.88

Fig. 33. Luncheon tendered to Italian commissioner Ernesto Nathan by the president and Board of Directors of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition Company, Palace Hotel, June 2, 1914. (#1959.087—ALB, 1:138, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Protestant Americans who feared a Catholic takeover took the opportunity to air their skepticism of the Catholic Church and their fears about the threats that Catholics posed to the body politic. W. P. Oliver of La Crosse, Wisconsin, noted, “As an American citizen . . . who hopes to visit the Exposition I want to protest against these trouble makers being recognized. . . . If this is to be distinctly a Roman Catholic Exposition I and thousands of others want to know it so that we may . . . arrange to spend our time and money in other directions.”89 From the opposite perspective, a Chicago chapter of the Guardians of Liberty—a Chicago-based anti-Catholic Masonic group—passed a resolution in favor of Nathan and supporting the exposition’s stand because Catholic protests were “UnAmerican.”90

Throughout this turmoil, the exposition directorate remained unmoved and refused to protest Nathan’s appointment. They welcomed Nathan and local supporters of liberal Italy with an elaborate ceremony in June when he came to dedicate the site of the Italian Building.91 The local Jewish community also celebrated his arrival. He remained the commissioner general of Italy to the exposition, although renewed protests occurred in 1915 over allegations that Nathan had defrauded the Italian government in his capacity as the representative to the PPIE. Despite the failure to remove Nathan, the Catholic press congratulated itself in raising awareness of Nathan’s faults. After Nathan’s humiliating loss in Rome’s June 1914 mayoral election to a Catholic monarchist, the Monitor had reported, “This tells its own story—the coming at last to the ‘turn in the lane,’ for Mr. Nathan, the world’s most notorious libeler of things Catholic. . . . There is not the least question that the world-wide Catholic protest made against Nathan, on his appointment . . . helped to bring about his defeat in the Roman elections Tuesday. That protest, begun by THE MONITOR. . . riveted the attention of the world on the infamous character of Nathan.”92 Two months later the paper again had noted, “In Rome, Nathan the unspeakable has dwindled down to a mere nonentity, it seems.”93 Later in the year, when Nathan returned to San Francisco for the fair, exposition officials and supporters of the liberal Italian government again wined and dined him.

Nathan’s successful tour at the fair, over the vociferous complaints of local Catholics, raises a question: if San Francisco Catholics held so much power, why did they fail to keep Nathan away from the exposition? Although the board included at least one local Catholic, it included even more members of the local Jewish community, suggesting the PPIE board had little personal or religious motivation to interfere in the Nathan controversy. Second, Nathan represented a foreign nation, and there was little the exposition could do to keep him from coming to San Francisco. Fair officials spent hundreds of thousands of dollars courting foreign governments. It was unlikely they would do anything to jeopardize those relationships, particularly as the war in Europe threatened the attendance of all European nations. Possibly offending the Italian government by asking it to recall the commissioner was likely not a step Moore or other officials wanted to take, even if they had seriously considered the Catholics’ objections.

Although Catholics failed in their campaign to keep Nathan away from San Francisco, they certainly succeeded in attacking his reputation and in convincing many Catholics, and perhaps non-Catholics, that he was a danger to their faith. The threatened boycott of the exposition, however, did not take place. After an initial hesitation and despite Nathan’s presence, Archbishop Hanna gave a benediction after the opening ceremonies.94 Although the protests failed to remove Nathan, they unified both San Francisco and American Catholics of all ethnicities and strengthened their sense of themselves as Catholic.95 They also highlighted differences within the city’s Italian community. Many older Italian immigrants were fervent nationalists and anticlericals who supported the very liberal Italian state that Nathan represented, and their stance explains the support that some San Francisco Italians expressed for Nathan.96 They may have resented the Catholic attacks on a representative of the government they supported. Moreover, Irish San Franciscans—who backed both the Monitor and the Leader—had historically voiced animosity toward their Italian compatriots. Although that tension was fading by the 1910s, this debate over Nathan may have rekindled old feelings. Both newspapers’ opposition toward Nathan may have been a disguise for anti-Italian sentiments. The PPIE, an event designed to increase international cooperation, here became a stage for ethnic and religious debates on a local, national, and international level. Local immigrant communities such as the Italians, Irish, Germans, and Chinese each latched upon the fair as a way to define both their status as Americans and their relationship to their homelands.

Not long after the debate about Nathan emerged, local Catholics found themselves involved in another dispute with the fair. The editor of the Monitor learned in August 1914 that PPIE officials had invited the American Federation of Patriotic Voters, a national anti-Catholic organization, to hold its annual convention at the fair. Although the Board of Directors’ first response to the editor’s objection was to assert that the “Exposition extended invitations to all organizations without distinction as to their religious, political or other beliefs,” their position quickly changed.97 By October, Moore admitted to the board’s Executive Committee that the group had been invited without knowledge of its members’ beliefs. Further, “he had learned later that this was an anti-Catholic organization, and that . . . the Exposition’s action in sending out the invitation to this organization might cause the Exposition unwillingly to offend an element in our population that there was certainly no desire to displease.”98 At an Executive Committee meeting the next week, Director Tobin, the only Catholic on the board, protested against the plan and informed his fellow directors that the invitation would surely cause ill feeling among all Catholics.99

Fortunately for fair officials, a tactless comment by a leader of the federation provided the exposition an easy way out of the situation, and in early 1915 the PPIE withdrew the invitation. A letter from the federation to the fair had stated that its members believed “that we need relief from a certain crooked grafting political machine posing as a religion.” Director of Congresses and Conventions James Barr informed the group in reply, “[This] is a direct attack upon a religious faith held by many. The exposition authorities are of the opinion that a universal exposition should be in the largest sense constructive and they neither desire nor can they tolerate the participation of any organization or exhibitor having a contrary object.”100 This anti-Catholic rhetoric gave exposition officials an excuse to retract the invitation and to acquiesce to the Catholics’ requests. The Monitor rejoiced in its victory and praised the exposition for respecting the rights of Catholics.101

The church’s power in San Francisco allowed Catholics to approach the fair from a position of strength. PPIE officials needed the backing of the Monitor and the church, or they risked very bad local and national publicity. Such publicity could threaten the fair economically. A local Catholic boycott of the PPIE could even prove disastrous. Although the objections to Nathan and the Patriotic Voters appear quite different from the protests mounted by the Chinese or Irish, they stem from similar concerns about the effects of “othering” on the distribution of social and political power. Nathan’s attacks on the pope and the Patriotic Voters’ accusations against American Catholics placed Catholics in the position of being the other. Honoring Nathan and the federation with invitations to the fair seemed to Catholics to validate anti-Catholicism and to threaten their standing in the Bay Area, and they believed that they should be able to counter it. They used their power in the city to keep the federation from the fair, even if they could not successfully fight Nathan’s appointment.

Local Irish, Catholics, and even Chinese Americans successfully wielded some influence with fair officials. Such was not the case for African Americans, who experienced outward discrimination on the fairgrounds and had no demonstrable influence with fair officials. In the local black community in the spring of 1915 a debate about the usefulness of an official day dedicated to African Americans erupted between those who hoped it might help showcase black achievements and those who worried it would simply perpetuate discrimination. As the correspondence with Du Bois suggested, fair officials did not arrange any celebration of a Negro Day when planning the PPIE. Shortly after opening day, a group of local blacks began to push for it, unleashing a heated debate in the local and state African American community.102 Backed by a number of local ministers and the publisher of the Oakland Sunshine, the San Francisco and Oakland Bureau of Information and Rooming House Association hoped to raise $1,250 to fund a celebration of Negro Day.103 The event would include a choir of black schoolchildren, athletic races of all kinds, and, organizers hoped, an appearance by none other than Booker T. Washington.104

Others in the community vehemently opposed the plan for Negro Day, regarding it as an offensive and patronizing offer.105 After receiving a letter outlining the plan, the editor of the Western Outlook responded: “We have no exhibit as a race, no representation on any of the boards, and nothing to point to with pride; and now comes forward a body of men to be used as a side show, to draw lines that they fight against, and for what? It smells bad to us, and we are against it. . . . As American citizens we can enjoy any day, county, State or national, but let us taboo Negro Day. We don’t want it, don’t need it, and should not allow ourselves to be used like a set of dummies.”106 The Negro Business League similarly opposed the idea, because with “nothing within the confines of the fair over which to make merry,” any attempt at a celebration would be a “miserable failure.” Finally, the league argued, the fair directors’ systematic rejection of every attempt by African Americans to contribute to the fair made it hypocritical to consider celebrating a Negro Day.107

African Americans throughout California used the debate about Negro Day as a way to critique the fair’s attitude toward their community and, indirectly, the position of blacks in the Bay Area. Mabel Wilson has demonstrated that blacks throughout the nation used such fairs as the PPIE to critique and assert their status in U.S. society.108 Bay Area blacks were no different. Attorney James C. Waters, Jr., argued in the Western Outlook that since African Americans had absolutely no role in organizing the exposition, the proposed Negro Day could be nothing more than “Jim Crow Day.” Moreover, he reported that his attempt to pin down the official exposition stand on race relations came to naught. Executive Secretary Taussig answered his request for clarification about equal treatment of blacks on the grounds by curtly stating that “no distinction is made on account of race, color, or religion.”109

Groups across the state voted to oppose Negro Day. The Interdenominational Ministerial Union of Los Angeles resolved that “Negroes cannot do now in four weeks what it has taken the white people four years to do.”110 The newly established Northern California branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) passed a similar resolution. It noted that since the celebration was without popular support, it would “have a tendency to point to our lack of civic pride, and humble us as American citizens.”111 Reverend Allen Newman stated the case even more clearly in a letter to the Western Outlook: “Knowing as I do that Mr. Moore . . . has emphatically refused to lend any influence in helping the promoters of this movement to secure the representative men and women of our race for such a celebration . . . my judgment leads me to oppose . . . Negro Day.”112 Newman’s explicit attack on Moore is the only such existing accusation, but the tenor of the other objections suggest that neither Moore nor other fair officials had done much to solicit opinions from local African Americans. Although little evidence remains about the extent to which the debate reached beyond California, at least one other black newspaper, the Cleveland Gazette, published a statement opposing the plan.113 If those outside California ignored the debate, it may have been because they were busy planning for the national emancipation exposition in Chicago that summer.114

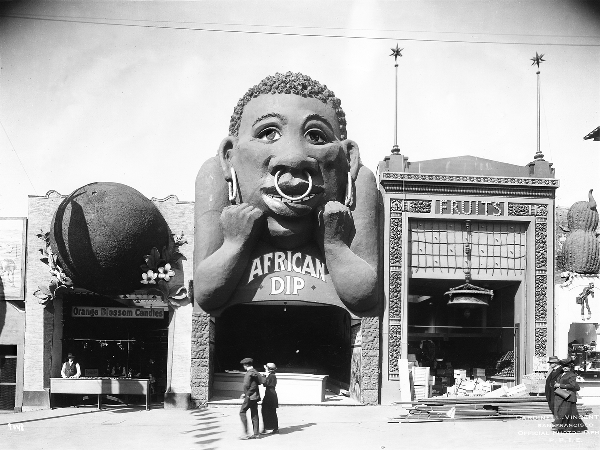

The debate over Negro Day suggests that local blacks understood the power of the spectacle created at the fair to racialize them as being outside of white American civic culture. Their many objections referred to the need to maintain their status as “American citizens” and suggested that they feared the effects of Negro Day on perceptions of that citizenship. As Lynn Hudson has pointed out, this debate over Negro Day took place in the larger context of Progressive Era race relations.115 The release of D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation in January 1915 drew the nation’s attention to the relationship between blacks and whites in the South. The film depicted blacks in harshly racist terms, focusing on the sexual threat black men posed to white women. The Bay Area’s black community mobilized against the film, a situation that certainly provided a backdrop to the debate over Negro Day. Concessions that depicted blacks in stereotyped, primitive, and negative ways—the Dixie Plantation, Somaliland, and the African Dip—certainly existed on the grounds, but no records reveal any organized protest by African Americans against these concessions, perhaps because they realized fighting them was a losing battle.116 Rather, they focused their energy on the question of Negro Day, which offered them an opportunity to take a proactive rather than a reactive response to white racialization of blacks. Debating Negro Day demonstrated the black community’s attempt to wield some control over how its members would participate in any racial formation on the fairgrounds.

Fig. 34. The “African Dip” in the Zone was only one of a number of attractions at the PPIE that displayed demeaning images of African Americans. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

The African American debate over Negro Day outwardly differed from the protests of the Irish, Catholic, or Chinese communities, which all received significant recognition from fair officials. Yet those differences should not obscure the basic issues, which remained the same. Some African Americans felt that a poorly organized Negro Day would do the same kind of damage to their community that Underground Chinatown did to the Chinese. Because African Americans had no real relationship with the exposition and little power in the city, their debate remained focused internally rather than on pursuing negotiations with fair directors, who had already demonstrated a lack of interest in dealing with them.

Despite their conflicts with fair officials about their participation in the fair, these communities each found ways to use the spectacle of the fair to their advantage. Catholics, in particular, found affirmation of their history at the fair. As soon as the fair opened, the Monitor praised the event’s depiction of Catholicism. From the statue of Father Junipero Serra above the California Building’s entrance to the “cowled figure of the priest” on the portal of the Tower of Jewels, the writer noted, “[o]n every hand in the length and breadth of the great exposition, the Catholic spirit that blazed the trail for civilization in California is in evidence.”117

Local Catholic residents had no trouble gaining permission to use the fair to pay tribute to the state’s Catholic roots. In July, members of the Junipero Serra Club of Monterey performed “The Landing of Serra” on the shores of the lagoon located in front of the Palace of Fine Arts. In a tribute to the Catholic tradition of honoring holy relics, Father Serra’s own vestments held a place of respect on an altar on the stage. According to the Monitor, “The land expedition of Don Gaspar de Portola with his Catalonian dragoons and muleteers and a few docile Indians . . . were shown awaiting Padre Junipero Serra . . . who sailed over the tranquil waters of the lagoon.” Written in blank verse, the pageant was “beautiful,” reported the writer, even though few viewers could hear the actors’ words because of the play’s outdoor setting.118 Local residents requested a repeat performance, and a month later the group staged the pageant in a larger and more visible venue, the Court of the Universe. A celebration of High Mass followed, truly imbuing the grounds with the “Catholic Spirit.”119

This display of the Catholic contributions to the “founding” of California affirmed the Catholics’ role at the expense of the conquest’s toll on native peoples. The coming of Father Serra brought disease, death, and virtual enslavement to thousands of natives, as well as the imposition of a foreign religious and social system. Anglos hastened the damage when they engulfed the state during the Gold Rush and shot and killed natives for sport or forced them to labor. For native peoples the Catholic presence in the state was nothing to celebrate, but the Catholics’ claim on California history fit neatly into the fair’s dominant narrative. The landing of Serra signified the beginning of the conquest of California that the white male pioneer finished eighty years later. According to this narrative, Catholic priests brought civilization and Christianity to the natives just as surely as the pioneers did. The absence of significant anti-Catholic sentiment in San Francisco made it easy to collapse the two narratives together and to forget the differences between missionary priests and gold-seeking forty-niners.120 The pioneer dominated the vision of California presented at the fair, but room remained for the padre, since his presence did not threaten the fair’s larger racial message. This story of California history placed Catholics as an integral part of conquest and as valued members of the state and the nation. In the social Darwinist framework of the fair, Spanish conquest was simply evidence of one superior race supplanting another. It was natural selection in action.

Although anti-Catholic rhetoric during the Progressive Era focused on the Catholic threat to the American body politic, at the PPIE, Catholics were envisioned as important members of California’s past and present. Catholics found their faith itself reaffirmed at the exposition. Fair officials welcomed Catholic priests to the grounds and allowed them to perform mass more than once. In 1914 the fair firmly had denied a request from a Protestant group to hold services on the grounds, rendering the welcome that Catholic priests received even more notable. In mid-July 1915, for example, exposition officials discussed having a special day in order to welcome Cardinal James Gibbons to the fair only a month after they tried unsuccessfully to cancel Protestant preacher Billy Sunday’s appearance on the grounds.121 The anti-Catholicism that emerged before the fair did not affect the PPIE. The Catholic Church’s ability to participate actively in the fair may be seen as an affirmation of its entrenchment in the power structure of San Francisco.

One of the most compelling reasons for understanding the PPIE as a site for the construction of racial, ethnic, and religious identities is that the event offered local and national groups ways to construct their own spectacles that they could display to fairgoers. As the celebration of German Day revealed, these special days usually involved parades, speeches, or pageants, presumably organized by the group itself. These large celebrations offered local residents the chance to assert specific visions of their relation to the U.S. body politic to both fairgoers and newspaper readers. Every day, local papers contained headlines, pictures, and articles about the various goings-on at the fair. In an era in which many residents read one or more papers each day, this publicity proved a powerful way for the fair’s visual and rhetorical messages to filter out beyond the grounds.

When Chinese American fraternal and political organizations met at the fair, they claimed the space of the exposition and included themselves in the public discourse surrounding the fair. The Chinese Nationalist League of America, the Chinese Students’ Alliance in the United States, the International Buddhist Congress, the Chinese Students’ Christian Association of North America, and the Asiatic Students’ Alliance—all met on the grounds during the late summer of 1915.122 In October, the United Parlor of the Native Sons of the Golden State, composed of second-generation Chinese San Franciscans, assembled on the grounds. This use of the grounds as a meeting place for local (and national) Chinese residents and immigrants presented a dramatically different vision of the Chinese in California society than did Underground Chinatown. As described in this chapter’s opening anecdote, the photograph of Chinese Students’ Day, with its rows and rows of young Asian men and women dressed in suits and ties and American-style dresses, presented a startling comparison to the robed, queued men of Underground Chinatown.123 By using the grounds in the same way that other fraternal and political organizations did, Chinese Americans challenged the racialized vision of their lives offered by Underground Chinatown and the popular press.

When ethnic Chinese visitors celebrated China Day and Chinese Students’ Day at the exposition, they downplayed traditional aspects of Chinese culture and instead focused on both China’s relationship to the United States and its recent technological advancements. In the Chinese context, the pageantry that other nations displayed evoked anti-Asian sentiment and old stereotypes, so the Chinese avoided drawing attention to their history in these events. Instead, they inserted themselves into the spectacle of the fair as Westernized, modern citizens of China or of the United States rather than as symbols of an alien “yellow peril.”124

Fig. 35. PPIE souvenir ribbon, 1915. (Collection of the Oakland Museum, gift of Ernest Isaacs.)

On St. Patrick’s Day, local Irish citizens staged an elaborate celebration claiming their dual position as Americans and proud children of Ireland. Their celebration differed, however, from the Chinese celebration of China Day because they shouted their Irish pride to the rooftops. They turned lights green and held an enormous parade, High Mass, and a concert of favorite Irish songs. More than sixty local Irish societies participated in the planning and were represented on the grounds, a number that suggests the breadth of preparation and the importance many local Irish attached to the celebration.125 More than seventy-five thousand people flooded the grounds that day, sporting green accessories of all sorts and their pride in their homeland.

Patrick McCarthy, former mayor, exposition director, and labor leader, served as honorary chairman of the celebration. His address to the crowd reflected the tenor of the event: “We are gathered here today to celebrate not only our national holiday, but to perpetuate the glory of our race . . . a race which has produced . . . men of great deeds in all times and in all kinds of human activities.”126 By choosing the word “race,” McCarthy indicated that the Irish organizers felt confident in unabashedly celebrating their Irish identity. Unlike the Chinese, who perceived the dangers of playing into white Americans’ visions of Asians, the San Francisco Irish had no difficulties claiming both Irish and American identities. An Irish identity did not, in this context, threaten their Americanness. Local Irish could proudly wave green flags and celebrate being both loyal citizens of the United States and proud sons of daughters of a romanticized Erin.

The event’s speakers declared their loyalty to state and nation. These declarations were particularly important in 1915, since the Irish hostility to Great Britain had led many Irish to sympathize with the Germans in the European conflict. Although the United States remained neutral, much popular sympathy lay with the British; thus Irish support of Germany only called more attention to their outsider status in parts of the United States. Attorney John J. Barrett, the keynote speaker of the day, gave a lengthy speech that began with a clear affirmation of the Irish community’s loyalty to the United States: “I know that I but give a tongue to every drop of Irish blood that stirs in this vast audience when I declare that, though the emerald emblem of the new-born nation across the sea is unfurled by us today in uncompromising homage, the Flag that now as ever is next to our heart and flutters in the breezes of its palpitating loyalty is the Stars and Stripes.”127 Despite the failure to depict an independent Ireland at the fair, the local Irish community drew on their position in San Francisco society to construct themselves as loyal sons and daughters of Ireland and the United States.

The Irish use of the grounds offered an explicitly anticolonial statement that called into question the fair’s larger imperialist goals. When the San Francisco Irish used the fair to call for an independent Ireland, they directly criticized the imperial system that placed the Irish as colonial others in relation to the English. That fair directors facilitated this display—because of the strength of the San Francisco Irish community—demonstrates the effects of local politics on the fair’s larger narrative.