Economic Partner, Exotic Other

After fourteen-year-old Doris Barr viewed a Japanese exhibit in the Liberal Arts Building of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, she recorded her disappointment that the display featured Western objects such as tennis rackets, bats, and clocks. She preferred the portion of the exhibit that featured old Japan with cherry tree blossom–lined streets and kimono-clad women to the image of new Japan, in which men wore Western-style suits.1 Japanese officials wanted the fair to demonstrate their nation’s emergence as a world power and its moves toward Western definitions of progress. They designed exhibits that featured examples of industrial and technical innovations alongside examples of traditional culture. The conflict between Barr’s expectations and the exhibit itself reveal one of many tensions that persisted on the PPIE fairgrounds between the agendas of the exhibiting nations and the expectations of visitors.

PPIE officials dedicated enormous amounts of time and money to convincing foreign governments to commit to participating in the fair. These campaigns took a range of forms, from world tours of Asian and European nations to the publication of newspapers and journals designed to advertise the fair across the nation and the world. Officials focused much of their attention on recruiting the participation of Asian nations—particularly China and Japan—because they believed that Chinese and Japanese involvement was essential to making the fair the kind of international event they intended. They wanted the fair to confirm San Francisco’s place as the dominant economic city of the Pacific and believed it would only happen if they could bring both Asian consumers and American and European manufacturers to the fair. One fair official argued, “The ‘Audience’ at this Exposition is the Pacific Area and the Orient is the proscenium boxes. Without a significant market as represented by participation here the interest of many foreign, and for that matter, domestic important commercial and financial institutions would diminish.”2 The national exhibits of China and Japan would also draw curious tourists. One piece of fair publicity promised: “Down Market Street will pass such Oriental pageants as the world has never seen.”3 Fair officials also knew that both nations were wary of committing resources to an event occurring in a state dominated by anti-Asian sentiment and political rhetoric.

California’s political culture undermined fair organizers’ determination to bring China and Japan to the event and fostered seemingly contradictory images of both countries for curious visitors. Japan and China were involved in a serious diplomatic dispute during 1915 and would not have perceived themselves as allies at the fair. But PPIE officials believed their fates were linked, so they dealt with the two nations in similar ways. Examining how fair officials interacted with these nations and with local Chinese and Japanese residents reveals first that local politics and priorities directly shaped the vision of China and Japan that was created for visitors to the fair. Second, it demonstrates that exposition officials intervened in California’s social and political life in ways that inadvertently subverted debates over the place of Chinese and Japanese immigrants in the state. Finally, it builds on the discussion of local Chinese participation in the fair to elaborate on the Chinese government’s role in attempting to use the fair to mediate anti-Chinese sentiment in California. On a national level, supporters of an “open door” with China had long worked for cordial relations with the Chinese and had been concerned about the impact of immigration restrictions and anti-Asian sentiment on their expanding business relations with China.4 The debates surrounding the PPIE, and the contrasting images of China created therein, reveal that this national political discussion played itself out in the cultural arena as well. Rather than providing clear-cut representations of China and Japan, the exposition became the site of competing visions of both nations, reflecting the larger discourse in the state and the nation.

Boosters pointed to the city’s proximity to Asia as a major reason that San Francisco should win the right to hold the PPIE. The Congressional Committee on Industrial Expositions cited this factor as a major reason for favoring San Francisco over New Orleans.5 Yet even at that moment the state’s anti-Asian sentiment threatened San Francisco’s bid. The New York Times reported in the fall of 1910 that President Taft had informed then governor-elect Hiram Johnson that if he truly wanted the fair for San Francisco, then he needed to rein in the state’s anti-Asian political activities until a treaty pending with Japan had been ratified. Only two days before the January 1911 congressional vote on the fair’s location, members of the state’s congressional delegation affirmed that state legislators had resolved to put off any anti-Japanese bills until after the location was decided.6 The relationship between the exposition, local and national politics, and the nations of Asia was fraught with conflict from the beginning.

U.S. fair organizers had long sought Asian participation in their events. Shelley S. Lee argues that at Seattle’s 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition city boosters’ economic goals for the event “mitigated nativist forces” in the region. This effort opened a space for more positive representations of Japan and Japanese Americans, even if it did not allow for concrete changes in the conditions of Japanese Americans in Seattle.7 China, however, refused to send an official exhibit to Seattle and remained in the eyes of most Americans a weak nation, so no such positive images existed of China at the A-Y-P Expo. By 1915, China had become a republic intent on asserting its position on the world stage, so PPIE officials eagerly sought the participation of both Japan and China. Since the PPIE was a much larger and longer event than the A-Y-P Expo was, it offered far more visitors a greater and more impressive array of events and exhibits featuring both Japan and China. California’s active anti-Japanese movement, however, threatened the project. The resulting political conflict reveals the extent to which fair boosters were willing to actively construct positive images of Japan, demonstrating that in San Francisco the “cosmopolitanism” that Lee identified at the A-Y-P Expo was translated into political and social action.

Many white Californians had long viewed Asians as threats to the state’s economic prosperity and to its moral and racial purity, and an active anti-Japanese movement thrived in the Progressive Era.8 Fair directors therefore faced a challenge in convincing these two nations to dedicate their resources to a fair held in such an apparently hostile environment. San Francisco itself had been the center of both anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese agitation, which eventually had resulted in national legislation excluding Asian immigrants. San Francisco contributed some leaders of the anti-Chinese movement, including Denis Kearney of the Workingmen’s Party and Congressman Thomas Geary, who in 1892 introduced the bill to extend the Chinese Exclusion Act for another ten years. The Exclusion Act stopped significant Chinese immigration to the United States, but a small stream still entered the country illegally. Meanwhile San Francisco’s Chinatown remained a vibrant center of Chinese culture.

Anti-Asian sentiment persisted in the city in the early twentieth century. When the city experienced an outbreak of the bubonic plague in 1900, panicked citizens blamed the Chinese and Japanese, and a local policy was instituted of “injecting Asiatics, both men and women, against the disease in public.”9 That same year labor leaders and politicians led a mass meeting in the city and called for the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act and for a new law to exclude the Japanese.10 The 1906 earthquake and fire further inflamed racial tensions as some local politicians actively pursued a plan to permanently relocate Chinatown from its downtown location.11 Japanese residents also experienced racial attacks and an economic boycott after the earthquake.12 When the city attempted to consolidate all of its Asian students into the “Oriental School,” its Japanese residents protested. The resulting dispute reached both the Japanese and U.S. federal governments, threatening the two nations’ burgeoning treaty relationship. President Theodore Roosevelt brokered the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907 that resulted in the city’s backing off its attempt to segregate the Japanese students in exchange for Japan’s limiting further emigration of Japanese laborers to the United States. The city’s and state’s anti-Asian sentiment therefore already affected not only local but also national and international politics.

This history of anti-Asian racism made the governments of China and Japan understandably hesitant about committing their resources to an exposition held in California. Nonetheless, both nations saw an opportunity to display their recent economic and technological achievements to a world audience.13 Chinese consul general S. C. Shu noted, “China at the Exposition expects to take the place to which she is entitled as a commercial nation. Never before has our nation had an opportunity such as the present to show to the world that China is an up to date and progressive nation.”14

Japanese officials similarly recognized the possibilities that the Panama Canal offered for the Japanese economy. They hoped that participating in the fair would stimulate economic growth and “strengthen the link of mutual sympathy which exists between the United States and Japan.”15 As Angus Lockyer argues, Japan had long sought to use international expositions as a platform from which to “mak[e] the modern Japanese nation,” although officials also recognized the challenge of countering Western imaginings and appropriation of Japanese culture.16 Officials of both nations hoped that a display of their national accomplishments might counteract the anti-Asian prejudice rampant in the United States during the Progressive Era. The political and social climate of California, however, continued to challenge these hopes.

Government officials in both Japan and China responded with cautious enthusiasm to the invitation to participate in the fair. Exposition officials eagerly courted government officials and merchants in both nations. As early as 1911, Matsuzo Nagai, the acting consul general of Japan in San Francisco, informed exposition president Charles C. Moore that he expected his nation to “take a deep interest in this Exposition.” He said, “National pride will find expression in these efforts and the sentiment of the Japanese people will demand that the showing made be dignified and typical of the best in Japanese life.” Thus, he warned Moore if other, offensive depictions of Japan should appear on the grounds, “the Japanese people would feel aggrieved and perhaps humiliated.”17 In the spring of 1912, Michael H. de Young, fair director, San Francisco Chronicle publisher, and prominent San Franciscan, traveled around the world publicizing the fair and spent extensive time in both China and Japan. He reported that the Japanese were particularly enthusiastic since they recognized the economic benefits of the Panama Canal.18 Japanese leaders demonstrated their enthusiasm when their nation became the first to choose a site for its national building in 1912, although later incidents delayed its official commitment until early 1914.19 Chinese officials voiced similar sentiments. In 1912, only months after the founding of the Republic of China, one Chinese minister told Moore, “China has just become a republic and will do her best in the development of her natural resources and in the promotion of her industry.”20 Attending the fair would offer China the chance to study modern agricultural methods. He and other Chinese officials also hoped the fair would help foster trade between his nation and the United States. Yet, at the same time, American exposition boosters in China reported among many Chinese a “feeling of resentment toward San Francisco” that complicated efforts to convince the Chinese government to participate.21 Clearly, citizens and officials of both nations were aware of the potential risks of attending an event in California, where anti-Asian sentiments ran high.

Fig. 36. Ground-breaking for the Japanese concession at the PPIE. Hundreds of local Japanese residents attended this event, showing their support for the fair. (Library of Congress.)

As indicated earlier, local Chinese residents urged others to support the fair, and Japanese residents did as well. A 1912 editorial in San Francisco’s Japanese American News argued, “It would not be trifling to say this exposition would be an ideal opportunity and a rare chance for us” to combat anti-Japanese sentiment.22 As did the governments of China and Japan, then, local residents thought that their ancestral nations could use the fair to help improve the status of the Chinese and Japanese Americans in California. This situation points to a distinction between these residents’ goals and the activities of other ethnic groups at the fair. Local Chinese and Japanese were acutely aware of their marginalized status and, unlike African Americans, had valued foreign powers on their side. They therefore used multiple strategies to assert their status at the PPIE.

California’s political climate continually challenged these goals. Moore, his fellow fair directors, and a host of other fair boosters in California, Washington DC, and Asia worked to ameliorate the effects of anti-Asian actions and legislation on relations with China and Japan. Sometimes this effort meant addressing issues in the city of San Francisco itself, as an episode in the fall of 1912 revealed. Just before the Imperial Japanese commissioners arrived in San Francisco to select a site for the Japanese exhibit, there appeared “on prominent billboards of the city certain posters which contained sentiments of an offensive nature to the Japanese.” Moore, realizing the gravity of the situation, quickly appointed a committee to investigate. The posters were immediately removed and did not reappear.23 Moore met with the consul general of Japan to discuss the presence of discrimination in the city. Nagai subsequently told Moore that the city’s popular bathhouses—the Hammam, Lurline, and Sutro—all banned Japanese from entry and that bars discriminated more “sporadically.”24 Nagai suggested, however, that rather than launch a campaign to eradicate such discrimination, it was better to wait and see “how the attitude of bartenders would be changed under the new improving circumstances.” Nagai seemed to believe that Japanese participation in the fair might ease race relations in the city.25 Developments outside the city, however, suggested that the problem was far from solved.

Exposition officials carefully monitored the situation on the national and local level. The first crisis arose when Senator William Paul Dillingham introduced a 1912 immigration bill that included a provision to deny entry to all aliens “ineligible for citizenship.” The subsequent flurry of contacts between Moore and his Washington correspondents, as well as local interests, demonstrated a real concern about the response to such legislation in Japan. George Shima, the famed “Potato King” and Japanese millionaire president of the Japanese Association of America, told Moore that the clause would be such an affront to the Japanese government and people that it very well might cause them to withdraw from the exposition.26 Moore assured Shima that although he did not believe that the bill would be voted upon in that session, “we shall oppose all such legislation with our utmost strength,” both publicly and privately.27 Other fair supporters also weighed in. David Starr Jordan sent Moore a copy of the letter of objection he wrote to President Taft in which he approved all parts of the bill except the clause that the Japanese found offensive, the one banning “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” Jordan noted that Japan had abided by the Gentleman’s Agreement and, he implied, was a better partner in exclusion than China had been. So he asked why the United States should embarrass Japan now and create unnecessary tensions between the two nations. His defense of the Japanese government echoed that of others who saw the Japanese as the “white race” of Asia and as being closer to Europe than to China or the rest of Asia.28 The Dillingham bill did not make it out of Congress, but its introduction prepared fair officials for the fight they took on the next year against the Alien Land Law.

In early 1913 the California State legislature began considering a bill to forbid Asian immigrants from owning land in California. Legislators had introduced similar measures in 1907, 1909, and 1911, but it was not until 1913 that anti-Japanese agitators succeeded in promoting a law that limited the length of leases and explicitly forbade “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land in the state.29 Although the Gentleman’s Agreement prohibited the entry of Japanese laborers, many Japanese already lived in the state and worked hard to make the state’s farmland productive. Wealthy Japanese began to hire cheap Japanese labor away from white farmers, becoming “active competitors for farm labor, farm land, and agricultural markets.”30 Frustrated white farmers watched their success with resentment while spouting increasingly racialized rhetoric. In both the 1909 and 1911 legislative sessions, federal pressure on the governor kept anti-Asian bills from passage. The situation became acute by 1913 when Republicans and Democrats introduced anti-Asian measures in both houses.31 Anti-Japanese legislation had become a powerful force in California politics, and supporters were increasingly aggrieved at what they saw as unjust federal intervention in state legislation. Governor Johnson faced tremendous pressure in 1913 to favor the Alien Land Law, and the newly inaugurated president was unwilling to directly interfere with the debate.32 The stage was therefore set for the passage of the law, despite the best efforts of PPIE officials.

Moore attempted to head off the legislation in January by sending President Pro Tempore A. E. Boynton a strongly worded letter in which he told him, in no uncertain terms, that if China and Japan chose not to participate in the fair, it would have a “disastrous effect” on the participation of other nations and make the international component of the PPIE a “failure.” Therefore, Moore urged Boynton, as a “Patriotic Californian,” not to introduce any anti-Asian legislation that could jeopardize this important event.33 Exposition officials, meanwhile, maintained supporters in Sacramento who lobbied against the anti-Asian legislation. Local businessmen telegraphed state politicians, urging them to oppose anti-Japanese legislation because it would affect “participation in the World’s Fair.”34

The PPIE directors sprang into action as soon as the bills were introduced. Moore called an emergency meeting at which he passed out lists of those legislators in danger of proposing anti-Asian legislation. He told directors to inform him if they had any “knowledge as to how any of these Legislators could be influenced.” Later that same day, nine fair officials visited Johnson to map out a strategy to keep such bills off the table. Johnson assured them of his support, yet he refused to commit to opposing the bills if they were introduced.35 Moore and others mobilized quickly because they feared if word leaked out about the legislation that Japan might not participate in the fair. Furthermore, they worried “this influence would be transmitted to China and the other countries of the Orient and to Europe, and that the Exposition . . . [would] lose much of its international character. . . . [These nations] would probably take it that this was to be a local or provincial exposition and act accordingly.”36

Exposition representatives repeatedly testified about the dangers that the proposed law posed to the fair. Progressive newspaper correspondent Franklin Hichborn reported on the last committee hearing on the bill: “The Directorate of the Exposition had made elaborate preparations to impress the farmers who were present, as well as members of the committee, that the Exposition is the most important thing in California, before which all other considerations must give way. . . . A complete moving picture outfit had been set up in the Senate Chamber. Scattered throughout the room were well-gowned women and carefully groomed men, wearing conspicuous badges—‘Do it for San Francisco.’”37 Hichborn was a Progressive Party supporter who voiced repeated skepticism of both the fair and San Francisco, but his report nonetheless reveals the impressive political and financial resources of the exposition.

Fair officials, boosters, and the local Japanese community worked hard in the spring of 1913 to defeat the law, but they faced entrenched opposition. During those final hearings on the bill, the well-groomed and elite pro-exposition spokesmen opposed a group of “very plain, rugged, untutored and uncultured men from the fields,” whom the audience supported with roars of approval.38 The bill’s rural supporters did not appreciate the attempts of wealthy San Franciscans to try to affect the debate, highlighting the class—and regional—conflict of the issue. One of those farmers was a former Congregational minister, whose oft-quoted statement reflected contemporary fears of miscegenation: “Near my home is an eighty-acre tract of as fine land as there is in California. On that tract lives a Japanese. With that Japanese lives a white woman. In that woman’s arms is a baby. What is that baby? It isn’t a Japanese. It isn’t white. It is a germ of the mightiest problem that ever faced this state; a problem that will make the black problem of the South look white.”39 Anti-Japanese propaganda regularly featured these accusations. Claims that the Japanese unfairly took good land from whites, that Japanese men threatened white women, and that miscegenation jeopardized American culture all struck a chord with fearful white Californians. Marriage between Asians and whites was already illegal in California, making the emphasis on the sexual danger and miscegenation so much hyperbole. Nonetheless, white Californians quite successfully portrayed Japanese residents as perils to the economic success of whites and to the purity of the white race and white womanhood.

Some San Franciscans failed to buy the exposition’s argument. Matt Sullivan, San Francisco attorney and president of the State Exposition Commission, testified against passing the land law with the caveat that “he would rather not have an Exposition at all, than to have the Japanese gain a foothold in California as they have in Hawaii.”40 Such testimony in favor of the fair was lukewarm at best and failed to challenge the racial assumptions that underlay the bills. Former San Francisco mayor and longtime proponent of Asian exclusion James Phelan argued passionately that maintaining the racial purity of the state was more important than the needs of the exposition. Phelan insisted: “The future of California . . . is of far greater importance than the success of this Exposition. And in saying this I do not believe for a moment that in enacting this land legislation you will jeopardize the success of the Exposition.”41 He raised the specter of a state in which “the whites submit to the reduced wages, reduced standards of living, and sink to the level of the Japanese.”42 The San Francisco Irish Catholic paper, the Leader, noted of the debate that “the interests of California must be made subsidiary to the interests of a private corporation, which, after all, is but a Barnum and Bailey on a large scale.”43 Although organized labor traditionally formed a key element of the fight against both Chinese and Japanese immigrants, the San Francisco Labor Council respected its agreement with fair officials to support the exposition and kept silent on the issue.44

Virulent opposition to the fair’s claims circulated outside San Francisco. A January editorial published in the Sacramento Union represented the anti-exposition and anti-Japanese feeling generated by the controversy over the bill: “Never was an argument made of frailer fabric than that advanced by the exposition officials, and thus indorsed by the Governor. . . . That is, to insure a Japanese tea-garden at the fair, we are requested to postpone, at least until after that event, those laws which are urgently demanded by American labor and the American land holder. Rome was burned to make Nero’s holiday; we are to sacrifice our welfare to make a Japanese tea-garden!”45 By reducing Japanese participation in the fair to “a Japanese tea-garden,” the author suggested that a Japanese exhibit would be an amusing racial display rather than the showcase of strong nation-state. He dismissed outright the claim that Japan must be treated as a respected foreign nation and source of potential new markets. The Union, the Sacramento Bee, and other interior papers continued to publish pieces with similar sentiments throughout the debate. Some concerned Californians voiced their opinions about the bill to President Moore himself, revealing the challenge fair officials faced in selling their point of view. B. P. Schmidt, a Sonoma farmer, told him, “All you rich men are fighting this land bill in favor of the Japanese, ignoring us altogether.”46 His accusation reflected many white California farmers’ intense hatred toward the Japanese and resentment of the perceived elitist attitude of fair officials.

Throughout the debate, Japanese people in Japan and in California found the Alien Land Law offensive, objectionable, and clearly discriminatory. Local Japanese seized upon the exposition as a way to fight the Alien Land Law. In late December and early January, even before the bills were introduced in the legislature, the Japanese Association of America wrote to Moore, asking for help in fighting the law.47 Moore assured Shima, as he had a year before, that exposition authorities would do what they could to oppose such legislation.48

Many in Japan doubted that they would be welcome in California if they attended the exposition.49 Japanese merchants, officials, and ordinary citizens all protested the affront. Many seized on the fair as a bargaining chip in their objections to the law. In February, the Japanese ambassador called on Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to tell him that Japan’s participation in the fair was at risk if the bill passed. Japan’s participation was aimed more toward showing “cordial relations between the two countries” rather than pursuing commercial motives, he told Bryan. Since Japan had not yet officially committed funds to the event, it was still possible the Japanese might back out of the exposition.50 In early March, exposition officials received notification from Japan that if the bill passed, “Japan will withdraw her support from the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, refusing to exhibit and prohibiting Japanese citizens from having any connection with the Fair.”51 In April, the presidents of the chambers of commerce of Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya notified President Moore of their “deep concern” that the bill’s passage would hinder the growth of commercial relations between the two nations.52 Newspaper articles that same week reported on unrest in Japan over the pending legislation and on threats that Japanese manufacturers would not attend the fair.53 The actions of the California legislature triggered a significant international response.

The bill passed by a huge margin in both houses despite this opposition. Although President Woodrow Wilson asked Johnson to delay signing the bill until the federal government could ensure it did not abrogate treaty rights, Johnson went ahead and signed the bill on May 19 without any further objections from Wilson. Scholars debate the reasons why the bill passed, when federal pressure and previous state governors (including Johnson two years earlier) had managed to oppose legislation in the past. Johnson biographer Spencer Olin argues that Johnson reneged on his earlier assurances to exposition leaders that the damaging bills would not pass because he was intent on revealing the Democrats’ “state’s rights” doctrine to be, in his own words, a “sham and pretense.” After President Wilson sent Secretary of State Bryan to meet with California legislators and attempt to defeat the bill, Johnson rebelled against this interference in what he believed was a state’s right to legislate. Olin also argues that Johnson believed that passage of the Alien Land Law was necessary for his political survival, for it redeemed him in the eyes of skeptical Californians for passing other “excessively radical” legislation. Finally, legislators found the California farmers’ sentiments against the Japanese simply more persuasive than were the pleas of wealthy San Francisco businessmen. Johnson himself explained to Theodore Roosevelt that the testimony of California farmers, insisting that “an alien land bill was absolutely essential for their protection,” convinced many legislators to support the bills.54

Moore and other directors quickly turned to pacifying the outraged Japanese and downplaying anti-Japanese sentiment in California. Japanese government officials made it clear to Moore that they were wary of committing themselves and their assets to participating in the exposition if anti-Japanese agitation continued to proliferate in California. Numano Yasutoro, acting Japanese consulate general in San Francisco, laid out his concerns to Moore in the fall of 1913. “There is a feeling in Japan,” he stated, “that the Japanese cannot get a square deal in California.” The rash of proposed anti-Japanese legislation and passage of the Alien Land Law forced potential Japanese exhibitors to confront the fear that “the Legislature of California—even during the Exposition year— . . . [would] introduce some legislation hostile to Japanese interests and calculated to shame us before the assembled world.” Stories of unfair treatment of individual Japanese on the streets of San Francisco, “at bars, in barber shops and other public places,” made visitors wary of traveling across the Pacific only to “be exposed to similar insults and humiliating discrimination.” Only the exposition director’s specific assurances and guarantees that Japan and its citizens could come to the fair “without fear of national or individual humiliation” would allay these fears.55

Fair officials also worried about the effects of the Alien Land Law on other regions of the United States, where citizens did not share the anti-Japanese sentiment of so many Californians. Right after the bill passed, President Moore reported on the “dangerous situation for [the] Exposition in Massachusetts,” where prominent Bostonian members of the American Peace Society were opposing their state’s appropriation for the exposition. He also asserted that “many Eastern newspapers have informed us they do not care to print Exposition matter in view of California Legislature’s attitude.” Perhaps even more damaging, he acknowledged in a confidential postscript, was the possibility that “many big Eastern manufacturers who have applied for exhibit space have expressed deep resentment and manifested possibility of withdrawing.”56 Despite these fears, the PPIE’s Washington DC correspondent reassured Moore that he had spoken with other leading progressives who were “inclined to support Johnson’s position” and that leading progressive eastern papers praised the bills, indicating more support outside the state than Moore imagined.57

Moore and other fair officials continued to smooth over relations with the local Japanese community and with representatives of the Japanese government. “We are glad to know that you are aware of the Exposition’s actions” regarding the legislation, he told the Japanese Association of America. The PPIE board took care to send copies of its resolutions opposing the legislation “throughout the country” to make its position clear.58 Some Japanese officials had come to believe by late 1913 that despite the Alien Land Law, the fair still offered a valuable opportunity to show off their nation’s achievements to curious Americans. The Japanese vice minister of commerce issued an official statement in which he noted that although officials understood the merchants’ anger at the Alien Land Law, “such participation [in the fair] would ease the situation, and the Japanese Government hopes that the Nation will send as many exhibits as possible.”59 In December, the U.S. ambassador to Japan informed Secretary of State Bryan that despite hesitation in some quarters, “many business men [sic], especially in Yokohama . . . feel that such representation will probably be very beneficial to Japanese trade and commerce.” He warned, however, that any further offensive legislation could prove disastrous to relations between the two countries.60

Fair officials continued meeting with Shima, K. S. Inui, another leader of the local Japanese American community, and representatives of the Japanese government throughout 1914 and discussed Japanese participation in the fair and good treatment for visiting Japanese.61 Some also credited a visit from U.S. ambassador George Guthrie to Japan for easing relations.62 Fair officials honored visiting Japanese officials with elaborate dinners and receptions. Numano thanked exposition officials in mid-1914 for “the kindly attentions showered upon Admiral Kuroi and his command during the past week . . . the luncheons, receptions, auto rides . . . were most heartily enjoyed, but best of all was the kindly spirit in which these evidences of good will found expression.”63 By showering the visiting Japanese with public praise and attention, exposition officials hoped to reassure them that they would be received with equal respect in 1915. Such events, which were often covered in local papers, contributed to creating an image of Japan as a nation deserving such respect and countered negative reports of the Japanese as threats to the United States.64

The fight over the Alien Land Law revealed the lengths to which PPIE officials would go to further the fair’s financial interests. They truly believed that if the law passed, Japan very well might boycott the exposition. If Japan did not come to the fair, then China would probably withdraw as well, and then the fair’s claim to be an event that would open the Pacific market for the United States and Europe would evaporate. Officials actively intervened in a statewide political battle to guarantee the success of the fair, and in so doing, they inadvertently complicated racial constructions that placed Japanese and white Americans in conflict with one another. By emphasizing the necessity of Japan’s participation in the fair, their public statements—reprinted in newspapers and propaganda—suggested that Californians viewed Japan and the Japanese as economic partners rather than as exotic others. As the advocates of the Open Door Policy with China attempted to intervene in exclusion debates, those who had an economic interest in developing a relationship with Japan also attempted to intervene here, depicting both China and Japan as valued international partners to the United States. Fair officials suggested that Californians shared common ground with the Chinese and Japanese at the exposition. These efforts reveal that those forces of economically motivated cosmopolitanism that Lee identified in the Seattle case as primarily rhetorical were transformed in the San Francisco context into concrete political action.65

China was less involved in the debate over the Alien Land Law, although the law applied to Chinese and Korean immigrants as well as to the Japanese. As did the Japanese government, the Chinese government continued to voice hesitations about investing in an exposition in a state that actively discriminated against citizens of its nation. Officials worried about the treatment their citizens would receive upon visiting California for the event. Would zealous immigration officials attempt to keep all visiting Chinese out of the state, even though the Exclusion Act applied only to laborers? Many of these fears stemmed from experiences at earlier expositions, particularly the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, where visitors were harassed and “subjected to continuous restraint and supervision which amounted practically to imprisonment.”66 Some Chinese merchants were detained for weeks in San Francisco en route to St. Louis while their papers were being processed, and the end of the exposition witnessed an immigration raid on the fair’s Chinese Village.67 If that treatment occurred in a state without an active anti-Asian movement, what could happen at a fair in California? Yet, if they were assured of fair treatment, one fair booster reported, “a great many Chinese merchants and educated men would visit the United States” during the exposition, “thus strengthening materially the friendly relations between those two countries.”68

Exposition officials dispelled some of the concerns that both Chinese and Japanese officials raised by urging the Bureau of Immigration to issue clear rules governing the entry of Asian laborers for the fair. A 1902 act allowed any foreign exhibitor at a congressionally authorized exposition to bring in workers deemed necessary for preparing or erecting an exhibit. In recognition of this act, the bureau issued a directive outlining the regulations governing Chinese laborers, who were specifically outlawed from entering the country under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. They were required to provide evidence of official employment, identification, and a $500 bond to immigration officers. Further, they were to return to China thirty days after their employment at the fair ended.69 Although C. I. Sagara of the Japanese Association of America told Moore that the regulations, which were also extended to the Japanese, were harshly criticized in Japan and “the results w[ould] be decidedly detrimental to the Japanese exhibit at the Exposition,” fair officials maintained that both the Japanese and Chinese governments would deem them reasonable once they were fully understood.70

After the announcement of these regulations, federal officials, fair officials, and Chinese representatives worked to find a solution that avoided the unpleasant experiences of St. Louis. When a nurse at the Angel Island hospital poorly treated a Chinese laborer brought to work at the fair, the Chinese Commission complained to immigration officials and elicited a rapid response. U.S. Immigration commissioner A. C. Caminetti promised that he intended to make the entry of Asian laborers as easy as possible, so he proposed a scheme to avoid the humiliation that Chinese workers had experienced in St. Louis. Rather than forcing Chinese laborers to line up for periodic inspections on the grounds (to ensure that all were present and accounted for), plainclothes immigration officials would meet with Chinese commissioners weekly to determine whether all workers were present.71 No existing evidence indicates any conflicts over the entry of the Chinese during the fair, suggesting that these pre-fair discussions successfully resolved the issue.

Chinese officials worried not only about their workers’ reception but also about how Chinese tourists would be treated upon arrival in the United States. When eight first-class passengers on a Japanese steamer were taken to Angel Island and held there for a day, a practice usually reserved for those of questionable immigration status, it became clear the officials’ concerns were warranted. Inui immediately informed Moore that the situation would “undoubtedly be a source of irritation in Japan.”72 No further documents of this encounter survive, but the incident and the treatment afforded the laborer in the Angel Island hospital reveals that Japanese and Chinese concerns about ill-treatment were well founded. Later that year, immigration officials acquiesced to the requests of the fair officials and the Chinese government and declared that “wealthy and refined Chinese coming first-cabin as visitors to [the] Exposition” would be exempted from the humiliating hookworm examination routine for all Asian arrivals. They would instead be released immediately from the ship upon its arrival in San Francisco.73 Such assurances were essential for convincing the Chinese government that their citizens would be treated with respect rather than contempt as they arrived in San Francisco.

That Moore and other fair officials engaged in these varied political maneuverings—from opposing the Alien Land Law to lobbying for reduced immigration restrictions—demonstrates the significance they placed on Chinese and Japanese participation in the PPIE. This importance empowered Chinese and Japanese officials and strengthened their advocacy for improved treatment for their citizens in California’s traditionally hostile political culture. Although the fight against the Alien Land Law failed, both Chinese and Japanese authorities succeeded in their struggle to gain respectful treatment from exposition officials, as evidenced by the elaborate dinners and receptions held in their honor, as well as by Moore’s lobbying for relaxed immigration restrictions. Although California was at the center of anti-Asian agitation, and had been for sixty years, the economic exigencies of the exposition enabled Chinese and Japanese governments to challenge California’s anti-Asian policies and culture and to offer alternative visions of their citizens as economic partners rather than as competitors.

The debate over the Alien Land Law revealed that California’s anti-Asian sentiment often expressed itself in cultural depictions of Chinese and Japanese as exotic others. Yet during the fair years, significant publicity portrayed both nations in positive ways, smoothing the way for their participation in the fair. Much of this change was owed to the PPIE’s publicity bureau, whose press releases became the basis of newspaper articles that described China and Japan as nations progressing toward American definitions of “modernity” and “Western” ways. An article on the Chinese exhibits, for instance, first described the elaborate displays and then praised them as being “characteristic of the new feeling of China, which . . . [has] declared for modern ways and put the old behind it.”74 A piece on the Japanese exhibit noted: “Japan will show to the world her culture and her civilization, her natural resources and industrialization, and give a new impetus to her trade and commerce.”75 These descriptions privileged white American culture but allowed for the possibility that Asia could emulate that culture, a distinct difference from the position of the permanent other that the Chinese and Japanese held in the minds of many white Californians. Not all publicity described the two nations in these ways, but these articles offered readers a new framework through which to understand China and Japan.

Other pieces of pre-fair publicity about local Chinese and Japanese residents described them as valuable members of San Francisco’s society rather than as unassimilable threats to the American body politic. Raymond Rast argues that post-earthquake publicists began to reimagine Chinatown as a uniquely San Franciscan attraction that was a cultural curiosity instead of a threat.76 One early article in International Fair Illustrated, an exposition-backed publication designed to publicize the fair nationwide, noted that the earthquake had “destroyed old joss-houses, out-worn idols, thieves’ quarters, ancient mercantile habits.”77 Publicists depicted San Francisco’s Chinatown not as a den of vice and iniquity but as an interesting and safe area of the city’s modern skyline.78 One piece of exposition publicity noted that “the gilded domes of her pagodas add striking features to the beauty of the new city.”79 Chinese residents themselves contributed to this image, as Look Tin Eli’s four-page spread on “Our New Oriental City” for a Western Press Association 1910 guidebook revealed. The new Chinatown was “more beautiful, artistic, and so much more emphatically Oriental” than the old one, he asserted.80 Departing from the separate, racialized neighborhood depicted in nineteenth-century publications, these images and texts presented a Chinatown integrated into greater San Francisco.81

Other publicity emphasized the integration of Chinese and Japanese Americans into American political life. This tactic must have pleased the governments of China and Japan and local Chinese and Japanese residents interested in demonstrating their value to the city.82 The San Francisco Standard Guide Including the Panama-Pacific Exposition reassured visitors that “the American spirit has caught the [Chinese American] population,” and “a goodly number of American born Chinese men and women . . . are voters.” Most important, it noted, “Chinese citizens of San Francisco, who are among the city’s most patriotic,” actively assisted in bringing Chinese exhibits to the upcoming exposition.83 Sometimes such praises even extended to the often-reviled Japanese. A San Francisco Chronicle report on Japanese farmers in the Central Valley characterized them as responsible for “breathing vitality into sterile soil.” The author assured readers that “when admitted to citizenship, the Japanese will certainly vote with as much independence and intelligence as any other race of naturalized citizens.”84 This portrayal of Chinese and Japanese residents as citizens and participants in American political life contrasted starkly with other articles that perpetuated California’s long-held anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese sentiment.

As Doris Barr’s visit to the Japan section reveals, the governments of China and Japan mounted elaborate displays designed to showcase their strength and progress. As with the ethnic and religious groups that used the fair to construct social and political identities, foreign nations also created identities at the fair. Officials of the youthful Chinese republic were particularly concerned about demonstrating their nation’s achievements and recovery from its recent civil war. Although China had participated in previous fairs, the PPIE was the first fair in which the nation would participate as a republic, and officials were particularly interested in demonstrating their internal stability to the skeptical West. Prior to 1912, the subservient nineteenth-century relationship between China and Great Britain meant that the Chinese themselves had not designed the exhibits. Instead, the Chinese Customs Service, under the control of Sir Robert Hart, had determined the nature of the nation’s exhibits.85 The PPIE therefore offered the first chance for the Chinese government to control its own representation and to determine its participation.

Visitors to the official Chinese exhibits encountered a combination of cultural artifacts and items designed to highlight Chinese efforts toward political and economic development and industrial progress. The “small walled city” of the exhibit enclosed a 100,000-square-foot area that included replicas of the Imperial Audience Hall in the Forbidden City; the Tai-Ho-Tien, or “Hall of Eternal Peace, used by the new Government as a Temple of Ceremonies”; and a Chinese home “furnished with tapestries, teak tables, lacquered furniture, intricate carvings and other works of art.”86 The most concerted effort to show off the nations’ progress toward modernity was in the enormous school display in the Palace of Education and Social Economy, which featured evidence of the nation’s new Westernized school system and the work of “thousands of grammar schools, middle schools, high schools, and colleges.”87 In the Palace of Transportation, the Chinese section featured the glories of modern-day transportation in China in an attempt to showcase both China’s scenery and its new technologies. The extensive pamphlet handed out to visitors in this exhibit illustrated China’s desires to appear “modern.” Echoing the inclination of American progressives to emphasize government efficiency and organization, the publication included organizational charts, maps of railway lines, and detailed information about the volume of mail delivered by the Chinese postal service.88

Fig. 37. Chinese Buildings at the PPIE. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

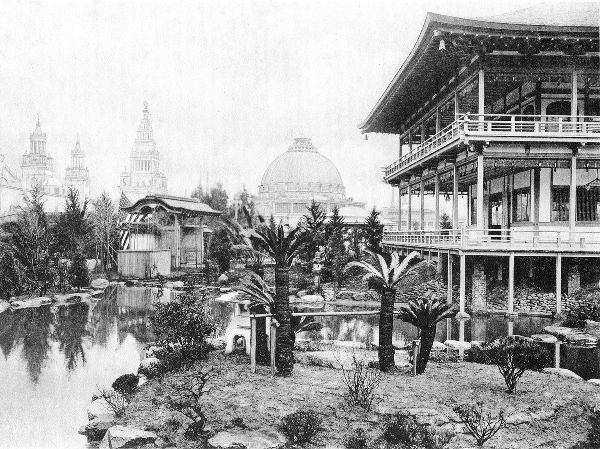

Japanese organizers also seized the opportunity to display both cultural artifacts and technological innovations to millions of potential visitors.89 They erected teahouses and a reproduction of the Nikko shrines on its four-acre site and dedicated key resources to exhibits in the Palaces of Manufactures, Agriculture, Food Products, Mines and Metallurgy, Liberal Arts, Education and Social Economy, Transportation, and Fine Arts.90 Japanese exhibits occupied more than 80,000 square feet of space in these halls—more territory than any other foreign nation had—plus an additional 145,500 square feet in its national building. Like China, Japan devoted space to its education system. Its exhibit in the Palace of Education and Social Economy featured examples of pupils’ work from the elementary school through college levels, as well as displays of the Japanese Red Cross Society, Tokyo’s public utilities, and photographs of the “poor houses” and “houses of correction” in the nation.91

Fig. 38. Japanese Gardens. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

At the fair the Japanese and Chinese representatives also took the advantageous opportunity to stage large public celebrations that would shape a particular image of their respective nations for fair visitors and readers of the local press. Some viewers even recognized the power of the fair to shape such images. “In a thousand different ways,” noted the San Francisco Examiner in March, “Japan is using the Exposition to interpret the Oriental mind to the Occidental understanding.”92 Japan hosted numerous impressive cultural celebrations at the fair, including a celebration of the New Year, a traditional Doll Festival, and the Iris Festival.93 The Japanese delegation took a leading role in hosting many social events as well, bringing together the PPIE Woman’s Board and Board of Directors, representatives from other foreign nations, and other key groups at many dinners and receptions. Although Chinese officials hosted fewer such gatherings, the local press regularly noted their activities. These articles offered remarkably positive coverage that again offered city residents and fairgoers visions of China and Japan that contradicted old stereotypes. The San Francisco Chronicle reported quite positively on an April dinner hosted by the Japanese commission, noting that “the toasts of the evening were indicative of the purpose of amity on the part of the Japanese commissioners.” Said toasts included that of Japanese commissioner Jiro Hirada, who proclaimed that Japan “stands with her arms outstretched and heart wide open to the friendship of the world.”94

Fig. 39. Japanese Red Cross exhibit. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

It is reasonable to assume that foreign officials realized the power of these spectacles. China’s approach particularly suggests that officials carefully orchestrated the content of these events. Although the dedication of the Chinese Building in March included Chinese music, little other pageantry occurred during the event. The featured musicians were local Chinese children who sang both American and Chinese songs in English.95 Reports mentioned their presence—and the San Francisco Examiner even included a picture—suggesting that the Chinese may have been trying to highlight the presence of a Chinese American population in the city.96 At the late September celebration of China Day, a sedate observation occurred in the Chinese Pavilion and featured an address by Kai Fuh Shah, Chinese minister to the United States. The San Francisco Chronicle noted, “No Orientalism for Chinese Programme,” and the report remarked that Chinese residents of San Francisco would celebrate the day with a “strictly orthodox Exposition program.”97 Kai’s remarks emphasized China’s long friendship with the United States and called for their continued economic relationship.98 The event included speeches by exposition and Chinese officials but none of the spectacle and pageantry that other nations usually featured in their celebrations. Its organizers rejected traditional Chinese costumes and displays in favor of a focus on the nation’s recent political and economic progress. Similarly, the featured speech at the Chinese Students’ Day, given by Y. C. Yang, a Chinese graduate of the University of Wisconsin, concentrated on China’s “new consciousness . . . new civilization and a new understanding.”99 The decision by organizers and participants to ignore China’s past and emphasize its future as a progressive republic suggests a belief that making connections with the “new” China was more important than reminding listeners of a history associated in the popular white American mind with imperial decadence and moral decay.

Fig. 40. China Day. (#1959.087—ALB, 3:130, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Japanese officials had no such qualms about asserting Japanese culture at the exposition. Fair officials bent over backward to make Japan Day a success. They issued numerous press releases about the event and forbade the Exposition Band from playing offensive music (i.e., The Mikado).100 Japan Day’s elaborate festivities included the ritual blessing of the national building by a Shinto priest and a huge parade containing floats designed to represent Japanese history.101 The active participation of local Japanese children, who were noted as such in newspaper reports, drew attention to the presence of the Japanese in California.102 The Japanese delegation’s choice to celebrate traditional holidays, such as the Doll Festival and the Iris Festival, at the PPIE suggests that they felt none of the qualms that the Chinese had about displaying aspects of their culture that white Americans could perceive as exotic. Such events echo Japan’s exhibitionary strategy at the 1910 Japan-British Exhibition in London, at which Lockyer argues Japanese officials sought to emphasize the value of their “civilization of an old and high order . . . into which modern civilization had been grafted.”103 It is likely that organizers of the Japanese exhibit in San Francisco had similar goals for the PPIE. They sought to highlight both their nation’s history and its future, taking a path unlike that of Chinese officials, who sought simply to focus on the future. These tactics reflect the fact that among white Americans, Japanese officials did not face the same stereotypes associating its ancient society with decay or decadence that China did. White Americans perceived the Japanese as primarily a military, economic, and demographic threat and not a moral one. Japanese officials may have believed they could safely celebrate their culture without fear of playing into white American stereotypes.

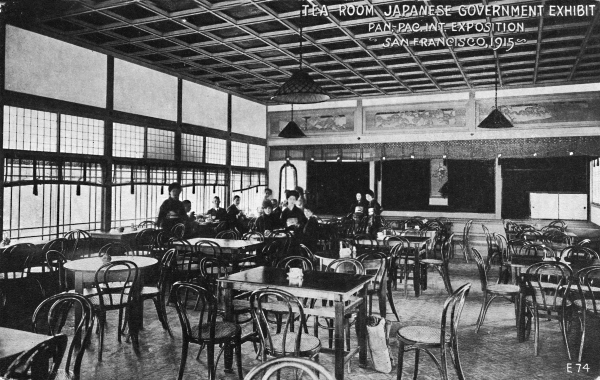

Fig. 41. At the Tea Room in the Japanese exhibit, visitors were served by Japanese women dressed in traditional garb. (Donald G. Larson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, California State University, Fresno.)

Another way to understand the power of these events rests in the interactions between people at the fair that contributed to the exposition’s social and cultural messages. These elaborate Japanese celebrations often facilitated exchanges between Japanese and Japanese Americans and fair visitors. Rather than static exhibits upon which fair visitors could gaze with interest, the Japanese hosted social events during which Japanese men, women, and children displayed their culture for fair visitors. The May 6, 1915, issue of the San Francisco Examiner featured an example of this interaction by running a photograph of a Japanese woman and a white woman, both dressed in Japanese garb, at the traditional Japanese Boy’s Festival celebrated at the fairgrounds. The two women posed for the camera, but they were also involved in the celebration and, presumably, in communicating with each other.104 Although a report on the Japanese New Year’s celebration summed up the participation of Japanese women with the note that visitors “mingled gaily with . . . the pretty little Oriental maids who grace the Japanese tea gardens,” the very act of mixing American visitors and Japanese workers (whether foreign or American residents) threw an element of uncertainty into the association that makes it impossible to characterize.105 Living exhibits, such as those on the Zone, are inherently unpredictable, and an understanding of that unpredictability must be included in analyses of these events.106 The conversations between these fairgoers had the potential to disrupt their expectations of each other and to introduce a human element not present in a static exhibit of Japanese culture or a staged performance.

Visions of both Chinese and Japanese as exotic and bizarre others persisted at the fair despite the attempts of the Chinese and Japanese delegations to use the fair to assert their nations’ equality on the world stage. Pre-fair publicity promised curious tourists that California’s proximity to the Orient would add an exotic touch to the exposition, one that would only be possible at a San Francisco event. “The displays from the Orient will be particularly lavish,” claimed one pamphlet. “The nations of the Orient, stirring from the sleep of centuries to the call of progress, will startle the Occidental mind with the most bizarre and novel effects ever witnessed.”107 Clearly, publicists hoped to lure potential visitors by drawing on Orientalist tropes of essentialism, passivity (only to be awakened by the West), and otherness. These “bizarre and novel” effects were unlikely to complement the developing political and industrial powers that the Chinese and Japanese governments sought to emphasize in their exhibits.

This vision of Asia replaced the stereotypical threats of gambling, opium smoking, prostitution, military invasion, and miscegenation with another equally racialized vision of Asia. In response to the “call of progress,” issued presumably by the United States, the Orient would display “bizarre” effects that would validate China’s and Japan’s status as others in relation to the United States. Such a vision emphasized the region’s inability to move forward on its own. It undermined the Asian nations’ attempts to display themselves as strong, modern states by crediting their development solely to their relationship to the West.

Publicists attempted to lure visitors to the city with depictions of its Asian American population as attractions that were to be viewed and consumed as the other exhibits at the fair were. This rhetoric stood in direct contrast to other images of the Chinese and Japanese as active participants in the state’s political life. To counteract potential visitors’ voiced fears of “the large number of Orientals in the city,” publicists promised visitors that San Francisco’s immigrant population was a harmless source of entertainment rather than an alien threat.108 Instead of de-emphasizing the Chinese presence in San Francisco in response to the public’s fears of an Asian invasion, publicists chose to turn Chinatown into an attraction to be viewed and again consumed during one’s visit to the city. A 1913 guide promised that “this quaint Oriental community” was the “most fascinating” of San Francisco’s attractions.109 Another praised the city for having “the most cosmopolitan population of any city in the world” and suggested that “a visit to these colonies is interesting and instructive.”110 In this context, immigrant communities became other educational (and exotic) exhibits to visit alongside the official exhibits presented at the exposition.

The Lure of San Francisco: A Romance amid Old Landmarks, a novel published in San Francisco in July 1915, encapsulated this consumerist attitude toward the Chinese in particular. The book’s heroine, a white native San Franciscan, attempts to convince her Boston beau of San Francisco’s charms, and during their tour of the city, they dine at both “Spanish” (Mexican) and Chinese restaurants. The authors described their Chinese meal in great detail:

[W]e seated ourselves in the big carved armchairs. Sipping the delicious beverage, we glanced toward the other tables, where groups of Chinamen were talking in a curious jargon and dexterously handling the thin ebony chopsticks. On the wide matting-covered couches extending along the sidewalls, lounged sallow-faced Orientals. . . . Snowy rice cakes, shreds of candied cocoanut, preserved ginger and brown paper-shell nuts with the usual Chinese eating utensils were placed before us. We tried the slender chopsticks with laughable failure. . . . We took a farewell look at the gilt carved screens and long banners, which in quaint Chinese characters wished us health and happiness.111

The novel implies that a visitor to Chinatown could expect to encounter novel foods, odd utensils, and exotic people. Each of these elements authenticated the experience. Although a novel, this book also served as a tour guide to San Francisco, as implied by its publisher, the Paul Elder Company, which also produced a good bit of fair publicity.112 Its appearance in July, halfway through the fair, also suggests it was intended in part to guide visitors through the city during their exposition visit. Its vision of San Francisco as a site for the consumption and viewing of foreign cultures fits very neatly with the image offered by fair publicity. Tourists were urged to view the Chinese residents of San Francisco as commodities who were available to entertain, supply, and feed them rather than as equal participants in American or international society.

This dual depiction of Chinese San Franciscans as both loyal American citizens and exotic others demonstrates the uneven nature of the racialization of the Chinese in early twentieth-century California. Although much publicity presented a safely tamed Chinatown, many white visitors still viewed the neighborhood as exotic and bizarre, subject to commodification and consumption, and not as the home of American citizens. This image had the potential to draw fascinated tourists to the fair and the city. Moreover, because popular stereotypes that associated the Chinese with gambling, opium, and prostitution still circulated in popular culture, this publicity constructed an impression of the Chinese as permanent others, incapable of integration into American society.

Neither San Francisco residents nor tourists had to look far to encounter persistent cultural stereotypes of both the Chinese and Japanese as threats to American society. Throughout the years leading up to the fair and during it, local newspapers published anti-Japanese and anti-Chinese articles alongside articles lauding China’s and Japan’s participation in the fair. Three days before the San Francisco Examiner published an editorial welcoming the members of the Chinese Industrial Commission to the fair, the paper had reported on the newest installment of a popular film serial with the headline “Elaine Is Liberated by Her Chinese Captors.” In that episode, Elaine “rejoins her family and in the resulting great joy the threat of the Chinese is forgotten.”113 With this and other such reminders in the press, however, it was doubtful that many white San Franciscans could forget the Chinese “threat.” Throughout the fair, papers published articles on the violence in Chinatown with titles such as “Chinese Tong War Is Brought to an End” and “Tongs’ Peace May Be Only Short Lived” alongside positive reports describing the activities of Chinese representatives on the ground.114 We cannot know what readers made of these articles, but certainly such sensationalism frustrated local Chinese residents. It reinforced decades of white Americans’ perceptions of the Chinese as dangerous, violent people who posed a menace to white society and particularly to white women.115 Papers published fewer such articles on the Japanese, but a pair of October 1915 articles published in the San Francisco Examiner detailing supposed Japanese plans for an invasion of the California coast reminded readers of the potential dangers that Japanese immigrants posed to the nation and to white women, in particular, who, the article promised, preferred to marry Japanese men.116

Exposition press releases echoed these assumptions that Asians were permanently outside of white American society when they foregrounded “exotic” Asia over the more “modern” image. One description of Japan’s displays at the fair brushed off Japan’s exhibits showcasing technological progress with the line, “What Japan has done to absorb western ideas is not as interesting to us of the occident as it is to that wonderful nation itself.” The author of the piece focused on describing scenes that fit the stereotypical Japan of the American imagination: geishas, tea ceremonies, exotic silks, and Sumo wrestlers.117 The author suggested these elements, rather than the artists and exhibitors who displayed the nation’s political, social, and technological changes, constituted the authentic Japan. While an appreciation of Japan’s heritage may be lauded, it is important to note that these images perpetuated Western fantasies of Japan, rather than reality, since they failed to include the nation’s emphatic moves toward modernization.118

The conflict over Underground Chinatown demonstrates the most extreme example of this tension between modern and exotic visions of Asia. As noted previously, this amusement concession drew on popular negative stereotypes of the Chinese to create an attraction that purportedly revealed the reality of Chinese American life to curious visitors. No vision of Chinese Americans as citizens appeared there; instead, visitors saw Chinese residents as drug addicts, gamblers, and prostitutes. Although the local Chinese community and its white supporters loudly protested the concession, it took the intervention of an official Chinese government representative, Chen Chi, to convince President Moore to step in and close the concession. Even after the concession reopened as Underground Slumming, the connections to stereotypes of the Chinese remained, making the change appear as less than sincere.

Underground Chinatown’s presence at the fair demonstrates how the fair became a source of debate over the relationship between California and China. That fair officials approved all of the Zone’s concessions, including Underground Chinatown, which started up not long after opening day and despite the concerns of the Chinese Committee of the PPIE, suggested that they took no sustained effort to keep the Zone free of images that might offend the local Chinese population. Yet how could Underground Chinatown and then Underground Slumming coexist with the fair’s other sponsored images of a developing China? If fair officials believed that China was essential to the fair’s success, why did they work so hard in the years before the fair to ease Chinese participation but then fail to rid the fair of the offensive underground attractions? Quite simply, the underground attractions existed because they reinforced racial stereotypes and were thus strong moneymakers. Moreover, they were located on the Zone, a space dedicated to amusement and immediate profit rather than to education and a space where critics and fair officials debated the line between the entertaining and the prurient. Many Zone attractions failed to make money, and fair officials were barraged with requests to bail out struggling concessions. Both underground concessions consistently made a profit, and fair officials seemed unwilling to jeopardize a moneymaking scheme. Most important, these attractions did not pose nearly the same kind of threat to the fair that pre-fair events had. China had already invested a great deal in its exhibits at the fair, and it was highly unlikely that the nation would withdraw partway through the event. Moreover, the persistence of these attractions demonstrates that fair officials, as a body, saw no need to fight these anti-Chinese images. Profit motivated their pre-fair politicking, their defense of Underground Chinatown, and their approval of Underground Slumming.

Fig. 42. Japan Beautiful exhibit in the Zone at the PPIE. (San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

The Japanese equivalent to Underground Chinatown was considerably more benign and raised no complaints from the Japanese community. Japan Beautiful featured an enormous Buddha guarding the gates to a complex that featured geisha girls serving tea, replicas of streets of Tokyo and Kyoto, sumo wrestling, and numerous opportunities for visitors to buy cheap replicas of Japanese goods. Robert Rydell notes that this “trivialization of Japanese culture” offset the image of progress that the official Japanese exhibits conveyed.119 No record exists of any objections voiced by the Japanese delegation to this attraction, and the only conflict that emerged around it involved the manager’s complaint that his workers were harassed at the gates of the fair. A local Japanese businessman ran the concession and hired local residents, and these factors may have helped insulate it from criticism. It may have played down advancements in Japanese culture, but it also made money for local Japanese residents. Its trivialization of Japanese culture more closely resembled that of concessions that featured European cultures than it did the powerful racial messages of Underground Chinatown, so no movement arose to shut it down.

Both Japan Beautiful and the underground concessions reveal the challenges facing Japan and China as they approached the PPIE and other expositions. No matter how hard Chinese and Japanese representatives worked to construct positive images of their nations, they were continually faced with Western perceptions of, and appropriations of, their cultures as exotic and different.120 They had to combat both negative stereotypes of their cultures and the expectations of visitors such as Doris Barr who came to the fair to see “traditional” culture instead of evidence of industrial progress. These visitors eagerly spent their dollars on Japan Beautiful or Underground Chinatown. This demand meant that PPIE officials gladly perpetuated these exotic images of China and Japan, further complicating Chinese and Japanese efforts to control their representations at the fair and contributing to an event full of competing agendas and images.

Asian exhibits drew visitors by offering a taste of the exotic and, in the case of the underground concessions, the morally titillating. The debates over these depictions, as with the discussions about the city’s development before the fair, demonstrate how deeply enmeshed the PPIE became in contemporary political discussions. Visitors also flocked to the Zone to watch scantily clad women perform in various concessions, launching yet another controversy at the fair. The Woman’s Board worked hard to make the fair a place where they would not be subject to sexual exploitation or to sexually suggestive shows. But the male fair directors demonstrated little commitment to this effort or much interest in ridding the grounds of such potentially profitable Zone attractions. The fair directors’ desire for profit again came into conflict with the agendas of other interest groups, this time making the fair into a battleground over gender and female sexuality and the place of vice in public life.