CHAPTER 3

FISH BOATS

“You have to admit, at least, that your books have foreshadowed a number of great inventions and valuable experiments.”

“No, a hundred times no,” cried Verne. “The submarine boat had been invented some time before I published my book Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.”

—Interview with Jules Verne, 1902

Human beings have longed to explore the depths of the ocean since well before the Civil War and the construction of the Hunley. Aristotle wrote that his student Alexander the Great, curious about the ocean, decided to plunge in using a glass bathysphere in 332 BCE. Chinese sources from 200 BCE report the construction of a submarine that could fully immerse carrying one person, travel to the bottom of the ocean, and return to the surface. Some adventurers have focused purely on the scholarly, wanting only to discover and learn, but others have been fascinated with the military potential. Military minds have always understood that the water could provide unparalleled cover for subterfuge.

Cornelis Drebbel stood gripping the sharply curved wooden edge of a man-sized opening in the year 1620. This device was his largest and most magnificent yet, and he felt confident enough in its success that he had invited the king to watch.

Drebbel’s machine was based on the drawings of inventor William Bourne, published a few decades earlier in 1578, but this was Drebbel’s third-generation prototype of the design. The frame was wood, wrapped in leather to create a hull, then slathered with multiple thick layers of grease to keep water from oozing in through the dark walls. Men sat inside at the handles of oars that stuck through the hull and let them paddle through the water. Drebbel had installed two floating pipes as a snorkel system to supply fresh air to the hardworking crew, as well as to the multiple spectating passengers who had been invited to ride in the belly of the machine for the occasion.

Drebbel lowered himself down past the edge of the opening and pulled the watertight door closed behind him. King James I, his royal court, and thousands of the citizens of London watched as the machine disappeared beneath the choppy surface of the river Thames. They collectively held their breath . . . then released it as a roar when the submarine reappeared a few minutes later.

Drebbel’s submarine has been recorded as able to stay submerged for three hours at a depth of 15 feet. The crew was either six or twelve men, depending on the account, working hard at the oars the entire time. No information is available on the size of the snorkel pipes, the volume of the boat, or the efficacy of the ventilation system. Some historians, given the ambitious estimate of three hours, have questioned whether Drebbel’s boat truly submerged at all. Instead, some theorize that the boat’s forward motion caused water to wash over the lowered bow of the vessel and provide the mere illusion of submersion to amaze the gullible crowds.

The Hunley had a heavy metal construction, but it still needed additional weights in order to submerge. Drebbel’s, in contrast, was buoyant wood; therefore, it would need even more attached weights to sink. If Drebbel’s submarine provided the same volume of gas per person as the Hunley, 952 liters, to each of six crew and two passengers, it would also be able to stay underwater for about thirty minutes before the people inside experienced problematic carbon dioxide levels. A submarine of this volume would require at least 7,600 kilograms of ballast to submerge fully in fresh water, equal to over four average-sized family sedans. If Drebbel’s boat had a crew of twelve rowers with three passengers, providing each with six times as much gas so that they could stay underwater for the described three hours, it would need at least 86,000 kilograms of ballast. This mass is about equal to forty-eight sedans, or half of a locomotive train engine. It seems like a challenge to integrate this much weight into a hull made of wood.

Modern-day shipbuilder Mark Edwards constructed a successful small replica of Drebbel’s supposed design, but the replica was propelled by only two oarsmen in a small space who dodged the problem of carbon dioxide by breathing from tanks of compressed gas. Historical accounts say that the alchemist Drebbel could completely refresh the air within his boat by dropping a few drops of an unknown magical mystery liquid on the floor. However, in the words of Simon Lake, a noted submarine pioneer who was well aware of the dangers of carbon dioxide, “Cornelius Debrell [sic] must have been either something of a joker or else he was much further advanced in the art of revitalizing the air than are any of our modern scientists.” Nonetheless, Drebbel’s constructions are considered the first submarine prototypes.

Over two centuries after Drebbel, German submarine inventor Wilhelm Bauer looked at his two panting countrymen slumped inside the hull of his creation. They had been trapped inside the submarine for hours, sitting and waiting for rescue.

The test day in 1851 had started normally. They had crawled, as usual, through the hatch in the angular conning tower above the bow and took their places: Bauer at the controls, and Witt and Thomsen each standing at one of the two massive hamster wheels that powered the boat’s propeller. Bauer gave the command. Witt and Thomsen lifted their legs and began to step on the spokes of the wheels, spinning them slowly like a giant human-powered waterwheel. The submarine began to move forward through Kiel Harbor in Germany.

But when Bauer had expected a graceful and smooth disappearance beneath the surface of the water, like an elegant metal seal, instead the Brandtaucher (“Fire diver”) had plummeted unexpectedly, caroming wildly in an awkward, unstoppable, and rapid descent down into a hole 17 meters deep. As she crashed into the seafloor and shuddered to a final stop the three men were hurtled unceremoniously into the bow of the boat. They pieced themselves together, shaken but uninjured. However, Bauer, Witt, and Thomsen slowly came to the realization that they couldn’t get the boat out of the hole. They were stuck.

At first, they just waited. And waited. For at least five hours, according to them, they sat, wondering when rescue would come. Their dive had been witnessed by onlookers; they figured it was just a matter of time until the German Navy hauled them back up to safety and fresh air. Someone had in fact noticed, and eventually the clanking of chains and anchors on the hull indicated that boats and divers were poking around the wreck site. But Bauer was growing concerned about the air . . . and the anchors.

All the men were panting hard, pale, and sweating. “[Bauer] himself, he said, had a splitting headache and would like to be sick.” Bauer knew the signs of carbon dioxide buildup. Their blood was becoming more acidic with every breath, and he knew that they did not have much gas supply left. He was also concerned about the anchors and chains that were striking the submarine so loudly, because he thought her thin hull might rupture from their repeated hits. He reached up a pallid, trembling hand, and he opened the seacock valve to flood the submarine.

Witt and Thomsen immediately pounced, one slamming Bauer down and sitting on his chest, the other scrambling to restrain his arms and close the valve. Wide-eyed, they yelled that he was trying to commit suicide and drown them too. But Bauer had opened the seacock because he was a man who wanted to live, and because he was also a man who understood physics.

The pressure inside the submarine was roughly 1 atmosphere because it got closed and sealed on the surface at 1 atmosphere. The pressure in the seawater outside, at a depth of 17 meters, was equal to about 2.6 atmospheres. Therefore, the pressure difference across the hatch of the submarine was about 1.6 atmospheres total. Converting the units, if Bauer wanted to force open the hatch to escape he would need to be able to move it against the 166 kilopascals of pressure pushing the hatch door closed.

The hatch door had a total surface area of roughly 1.5 square meters. One hundred sixty-six kilopascals of pressure from the water times the 1.5 square meters of the door is equal to 249,000 Newtons of aquatic force shoving against the door.

Let’s put that into relatable units; I choose to describe the force in units of Rachel. I personally am 160 pounds’ worth of human-being mass, mostly comprised of cake, which in metric units is 72 kilograms. Therefore, according to Isaac Newton, to calculate the force exerted by me on the Earth, my 72-kilogram mass gets multiplied by the rate at which Earth’s gravity wants to accelerate me downward, which is 9.8 meters per second squared. Seventy-two multiplied by 9.8 is a total downward force of 711 Newtons.

Therefore, I exert 711 Newtons of force on the ground just by standing there, doing nothing productive, converting oxygen to carbon dioxide. The force on the hatch from the water was 249,000 Newtons. If Bauer wanted to leave the submarine, he would have needed to be strong enough to lift the 350 Rachel Lances standing on the hatch door.

Bauer opened the seacock because he knew that he needed to equalize the pressure differential. If he could flood the submarine and bring the pressure inside up to 2.6 atmospheres, the total pressure difference across the hatch door would drop to zero. The door would swing open with ease, and all three submariners could swim to safety. More likely the door would have blown open violently as the buoyant air tried to escape and shoot to the surface, but either way . . . exit pathway achieved.

Talked down by Bauer and his mastery of the laws of pressure, Witt and Thomsen released their captain and allowed him to flood the sub. The increase in the partial pressure of the carbon dioxide was temporarily difficult to tolerate, leading to gagging and choking, but the submarine flooded quickly and the pressure was equalized. The trio got blown out through the hatch and rocketed safely to the surface like they were the “corks of champagne bottles,” as Bauer later put it.

Bauer, Witt, and Thomsen were the first three submariners ever to successfully escape a submarine. They did it in the year 1851, and they did it through a mastery of the scientific principles of the underwater world. A few decades later, the Brandtaucher was recovered from its mud hole in the ocean and conserved. It is presently on display in a museum in Dresden, Germany, and is the oldest submarine ever recovered.

By the time of the Civil War ten years later the military distaste for submarines was globally evident. They were dubbed “infernal machines,” a common phrase used pejoratively to describe a variety of new inventions of war that could not be openly and fairly seen by their targets. The phrase was meant to conjure imagery of hell, and to suggest that these Satan-born stealthy devices were beneath the civilized warfare of respectable and dignified men. A respectable man looked you in the face and gave you a chance to shoot him back. In the South, the situation was a bit more dire, and therefore a bit less judgmental.

At the time of Lincoln’s election in late 1860, the eleven states that would become the Confederacy had a potential fighting population of only 1.3 million white, male citizens in the age range of fifteen to fifty years old. The Northern states had a population of 5.6 million from the same demographic, over four times as many as the South, and in addition another 83,759 fifteen-to-fifty-year-old free black men, many of whom would prove eager to enlist. While women were not officially permitted in combat roles, modern research has found evidence of numerous female soldiers fighting undercover as men for both sides, and at least one black woman fighting undercover as a white man for the Union. However, not enough of these soldiers existed to sway the total numerical estimates. At the time the war started the Union Navy had a fleet of ninety fighting ships, and although not all were in superb condition, in contrast the navy of the Confederate States would later be described by historians as “nonexistent.”

The citizens of the “Southern Slaveholding States” had watched the 1860 presidential election with intense apprehension. Lincoln, one of four candidates, was a member of the Republican Party, a party later protested in Georgia’s declaration of secession as having the “cardinal principle” of “prohibition of slavery.” Many plantation owners, firm in their belief that “none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun,” were concerned that a victory by the slavery-eschewing Republicans would lead to an end to their right to own slaves, and therefore an end to their estates and their livelihoods. After Lincoln’s victory the cotton plantation owners led the charge. Starting with South Carolina, the collection of states one by one announced their determination to leave the Union.

The first official battle of the Civil War is widely considered to be the Confederate assault on Fort Sumter, an island fortress built just outside the harbor mouth of Charleston, South Carolina. The Union troops occupying the fort had been barricaded there for months, fighting off hunger and warily watching the escalating tensions between North and South following the declarations of secession. On April 12, 1861, the Confederate government decided it was time to take the fort, and on April 13 they succeeded. Sometime in the hours between, the bloodiest war in American history had begun.

Many in the South were confident there would be no war; they expected to leave the Union peacefully and without argument. As later stated by Confederate officer George Washington Rains, the war was “entered upon unexpectedly, as it was everywhere supposed in the South that the North would not seriously oppose the Secession of the States.” A few months before the battle at Sumter, South Carolina senator James Chesnut Jr. had even been heard offering to drink all the blood shed as a result of secession because he was confident there would be none. So when the war did begin, the Southern states found themselves outmanned, outgunned, and short on supplies.

The obvious plan was to starve them out, and the Union immediately began a blockade of all the major Southern ports. They named the strategy the Anaconda Plan for the way they thought it would slowly choke the populace into submission.

Confederate president Jefferson Davis realized the strategic disadvantage of the relative lack of a Southern navy and promptly sent out a plea to the people for help. His wording did not hide how he felt about the fact that what he perceived as a simple secession had turned into a war, stating that he was “inviting all those who may desire, by service in private armed vessels on the high seas, to aid this government in resisting so wanton and wicked an aggression.” In other words: Bring your private boats, we’ll declare you and the boats to be part of the Confederate Navy, and together we’ll show them they can’t demand we stay.

The Confederacy offered monetary prizes to incentivize the destruction of Union ships, and the dollar amounts could be staggering. The prize value for each ship was determined case by case, but the privateers kept almost all the reward. The reward included the value of the ship in addition to $20 per man aboard, so for a massive vessel like the USS New Ironsides the bounty for the lives of the crew alone would be about $9,000. This amount of money, equivalent to about $250,000 in 2018 even before adding on the cost of the ship herself, was sufficient to entice many young men who dreamed of making a fortune as well as those who dreamed of serving their home states. Three of these young men were Horace Hunley, Baxter Watson, and James McClintock.

An 1861 illustration of the Anaconda Plan.

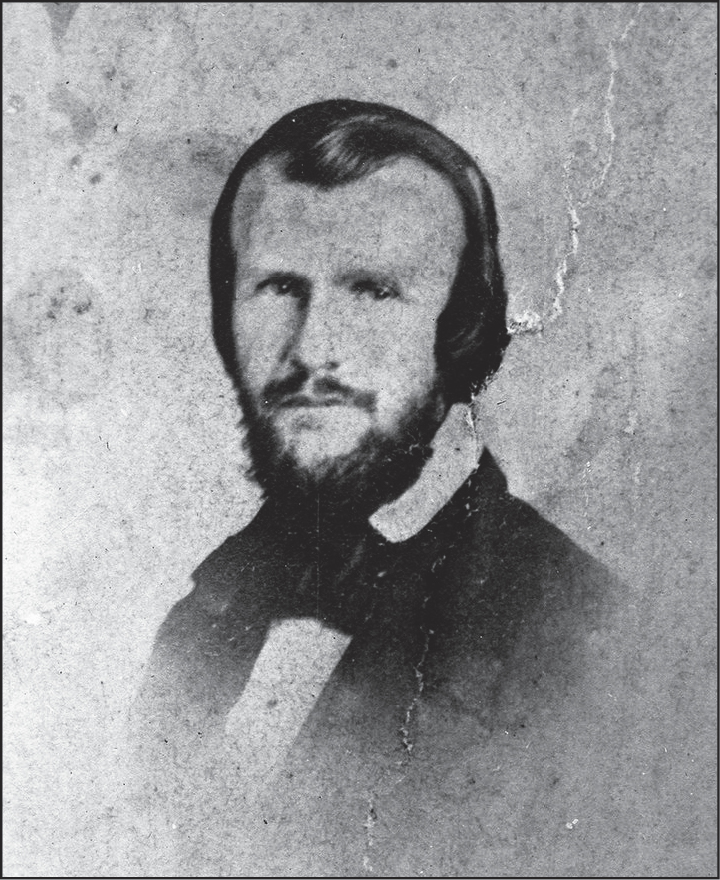

Horace Hunley was born into an average farming family in Tennessee, but during his adulthood he became a wealthy man, and like many wealthy men he left behind prolific records of his life. The one confirmed portrait of him shows a young face with a sparse mustache and beard poised above a high, starched collar, and narrow-set eyes somberly focused on something to the left of the photographer. He was a lawyer by trade with a degree from the university now known as Tulane, but his real motivation, his real passion, seems to have been money. After law school his adventures included holding a seat in the Louisiana state legislature, dabbling in the export business, and working periodically in a highly valued and well-paid seat as a New Orleans customs collector. Hunley’s younger sister, Volumnia, was married to a substantially older, fabulously wealthy sugar-plantation owner named Robert Ruffin Barrow, and Hunley unabashedly and repeatedly played that connection to get loans from Barrow to fund his moneymaking exploits. By 1860, the successful thirty-seven-year-old Hunley was able to purchase his own eighty-acre sugar plantation in Louisiana, including at least the minimum of twenty slaves required to call it a plantation. The outbreak of war presented blockade-running as a new industry, and the entrepreneurial Hunley jumped at the opportunity.

Horace Lawson Hunley.

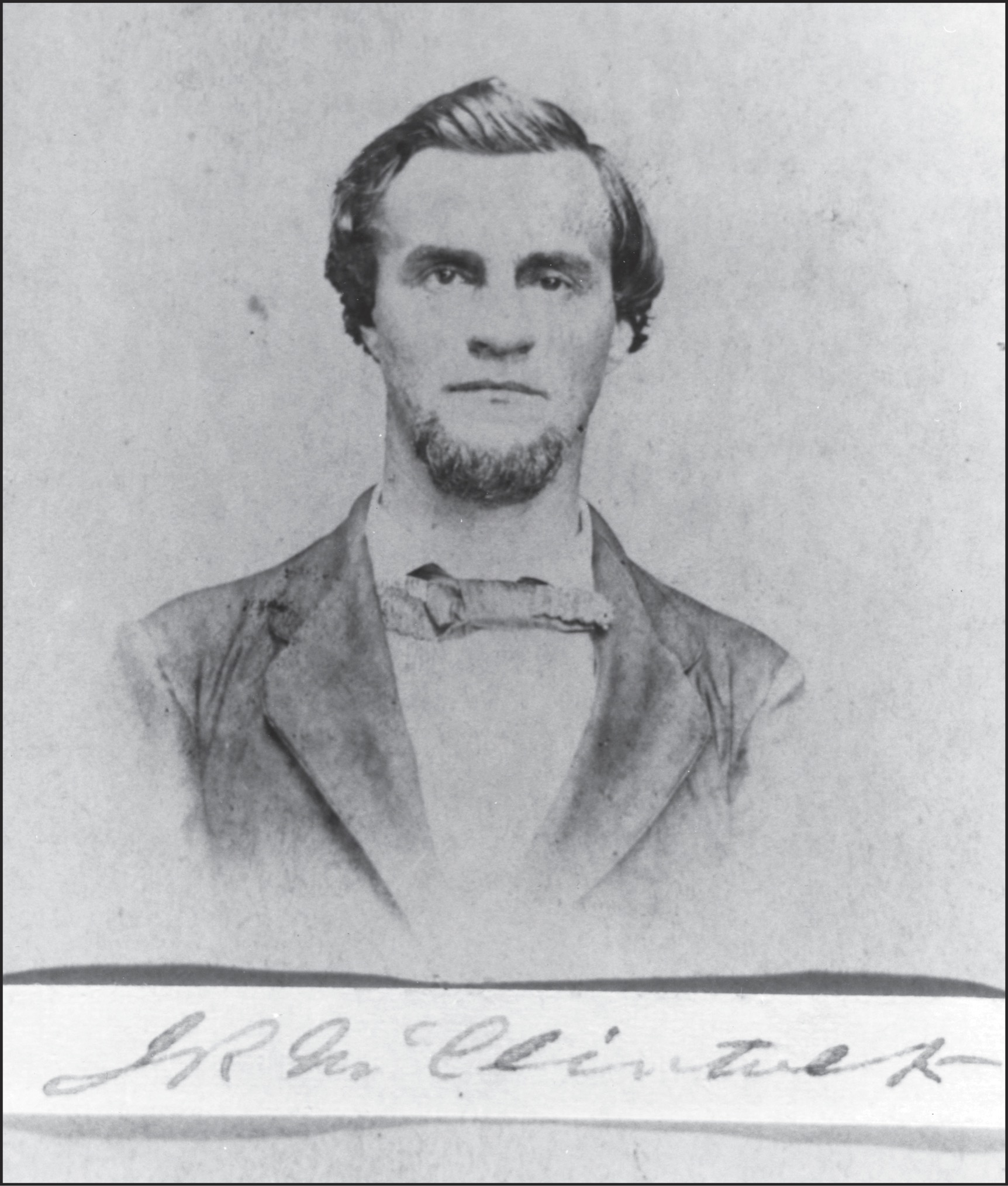

The life stories of McClintock and Watson are far more mysterious. They were true engineers: They were machinists and inventors before the title of “engineer” required an official university degree, back when it was a designation ascribed to a person who built and created. Portraits of James McClintock show a luscious swoop of hair, just beginning to recede at the temples, and heavy black eyebrows that frame deep, serious eyes. His broad mouth, set into a thin line, reminds me of the chagrin I often see in the faces of my modern-day fellow engineers when we are asked to waste time on frivolous tasks like sitting for a portrait.

James R. McClintock.

McClintock and Watson worked with their hands, and at the start of the war they invented a machine to mass-produce bullets for use by the Confederacy. McClintock, a former riverboat captain known for his engineering work on steamboats, made an effort on April 22, 1861, to organize his brethren handymen for the cause. He took out ads boldly declaring “ATTENTION, ENGINEERS!” in the local newspaper and held a meeting where he asked his fellow mechanics and inventors to join the newly formed “Louisiana Associated Engineers’ Rifle Company” on behalf of the Confederate States.

At some point in 1861, while living in their mutual city of New Orleans, Hunley, McClintock, and Watson crossed paths. Their prototype boats would be largely financially supported by outside investors seeking to share in the bounty, but in general Hunley was the moneyman of the group, and McClintock and Watson were the designers. I have no evidence to support the theory, but I like to think that Hunley showed up to McClintock’s advertised meeting that Monday night in the spring of 1861 looking for a wrench-turner who could help him beat the blockade. What is known is that by the following fall, the three men began to build their first design.

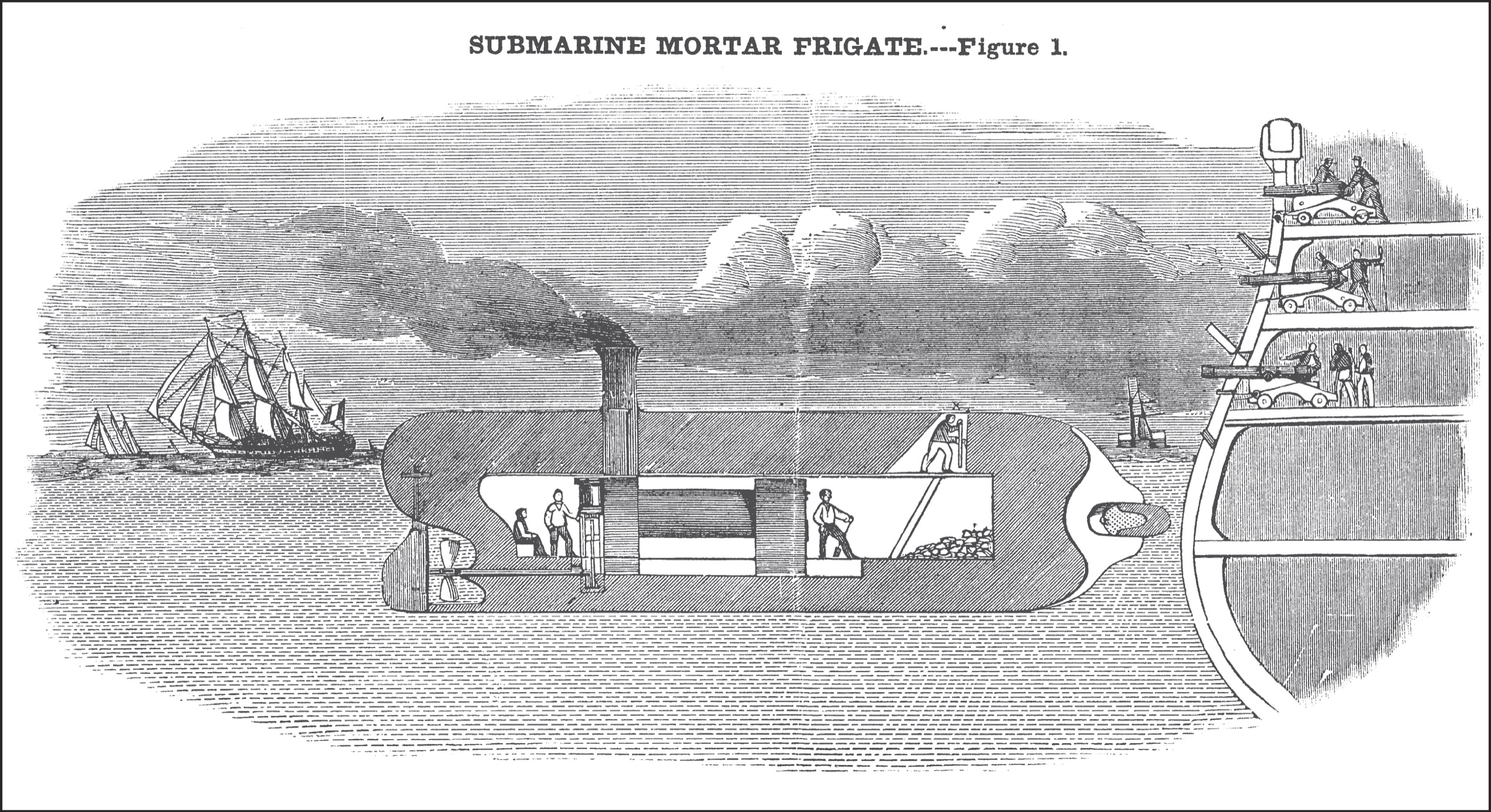

Early design concept of a torpedo-carrying submarine boat.

McClintock would later claim that he thought up the idea of a bomb-laden submarine on his own, without any outside inspiration. However, machinist John Roy wrote in his diary on April 22, 1861, that several days earlier he had carted an old copy of Scientific American with him to the foundry where both he and McClintock worked, and shown around an illustration of a torpedo boat that he thought could help menace the Union fleet. It seems plausible that this drawing may have been the reason that McClintock called the meeting: to search for more engineers to help him plan and build.

The submarine later dubbed the HL Hunley was not the first construction of Hunley, McClintock, and Watson’s. Their first confirmed, known boat was the CSS Pioneer, the only ship of the three they built to receive an official Confederate commission and therefore to have a “CSS” designation. It carried only two men and was shaped from the repurposed panels of the boiler of a steamship, presumably pillaged by steamship engineer McClintock from some local graveyard of parts. Like the Hunley, she was powered by hand crank and had a generally cylindrical design. Unlike the Hunley, the bow and stern of the Pioneer sharpened to conical points, as if two waffle cones were stuck together by a short section of tube, instead of flattened vertical wedges.

Because of the pointed, conelike ends, the Pioneer turned out to be irredeemably unstable. According to McClintock himself, the design was extremely subject to small changes in weighting and position; shifting the ballast weights even a few inches forward or aft made her tip wildly and uncontrollably. This instability was not a great operational feature in a submarine. The designers therefore declared her unfit for service on the open ocean, but they still used her to patrol Lake Pontchartrain, the massive inland lake nestled in the crook of the crescent-shaped land mass that forms the city of New Orleans.

Additionally, when the tiny boat was fully submerged, the crew inside didn’t have a visual frame of reference to see what was happening outside, or if they were even making forward progress through the water. McClintock provides one account of the crew, subject to an unstable plummet, driving the vessel headfirst into lake-bottom muck. Unaware that they were firmly stuck, they sat and continued to crank relentlessly, assuming they were moving the entire time. The crew in McClintock’s retelling seems to have survived their unfortunate incident, but the Pioneer still carries a different fatal association.

Simon Lake is widely considered to be one of the two or three true “fathers” of modern-day submarines. In the year 1918 he wrote a book, and he took care to include a brief history of the devices that had predated his designs. Lake retells a story about the CSS Pioneer thirdhand, courtesy of a photographer friend who heard it while in New Orleans from a supposed firsthand witness. The same friend supplied Lake with a photograph near Lake Pontchartrain for use in his book.

Slaves were forced to pilot the CSS Pioneer on a test run, according to the story. The prototype boat “was the conception of a wealthy planter who owned a number of slaves,” and the planter wanted to show off the diving capabilities of the submarine on her trial run. Taking “two of his most intelligent slaves,” he briefly showed them how to hold the tiller and turn the propeller before closing them into the vessel and launching it into the bayou in front of a crowd of invited spectators. The submarine never reappeared, and the planter vehemently and loudly swore his frustration at himself for trusting the two slaves who—in his opinion—had clearly just stolen his device to travel north to their freedom.

Years later, the submarine was found during a dredging operation, sunk in the mud close to where it had been launched. Lake quotes the alleged firsthand witness, who had earlier reported the values of the slaves at $1,000 per man when they went into the little boat: “And do you know, suh, when they opened the hatch them two blamed niggers was still in thar, but they warn’t wuth a damned cent.”

In 1864, US Navy fleet engineer William H. Shock was charged with inspecting the CSS Pioneer, which had been recovered from the lake bottom a few years earlier and was sitting on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain. Along with a technical drawing he commissioned of the Pioneer, he included a letter that reports a Confederate submarine test that is remarkably similar to Lake’s tale, stating that “two contrabands [slaves] . . . were smothered to death” inside the vessel.

The number of slaves in both the stories of Shock and of Lake’s photographer friend matches the number of men needed to pilot the CSS Pioneer and another submarine later found in the area. The tests in both stories occurred at the location that is known to have been used by Hunley, McClintock, and Watson to test their vessels. Hunley and McClintock were both, at that time, plantation owners with slaves, just as the inventor in the photographer’s story was a plantation owner with slaves.

Machinist John Roy was living in New Orleans in the fall of 1861. His daily diary records his attempt to go watch the public demonstration of a “sub marine boat for blowing up ships” that took place on November 3, 1861, right around the time when Hunley, McClintock, and Watson would have begun testing. Roy frustratingly went to the wrong location and missed the demonstration, but other diary entries show that he and McClintock both frequented the same foundry, and that the men almost definitely knew each other well. If McClintock were arranging a public demonstration of his submarine prototype, Roy would probably have been invited.

The men lowered themselves into the foreign metal device, having only a cursory understanding of how the various levers and gears were supposed to work. They took hold of the crank and must have experienced the terrified certainty that the only way out of this situation was through it. They cranked furiously, stuck in the mud, with nothing to tell them that they were going nowhere, and eventually, feeling as if they were choking on their own breath, they became confident in the dawning realization that this experience would be their last.

Historian Mark Ragan, working “under the auspices of the Friends of the Hunley,” did a massive amount of archival digging after Cussler announced his find in 1995. Ragan, who refers to himself as “Hunley project historian,” was the first to wrest the Shock letter from the microfilm caches of the National Archives. He was so enthralled with its “historical significance” that he stated in one of his books about the research that this letter was “worth reprinting in its entirety.” So, in the book, he included the entire text of the letter to make it more accessible to the world. With it reprinted and republished, nobody would ever need to look up the original microfilm and read it themselves. The Friends of the Hunley later used the drawing from Shock to build a full-sized model of the CSS Pioneer, and they now display the model in the lobby of their museum. By 2000, Ragan was serving on the board of directors of the Friends of the Hunley.

There is one major problem with Ragan’s archival work, and his reporting: He changed a key word in the story. Where the original, handwritten Shock letter reads that two “contrabands” died, Ragan altered the word in his transcription to read “men” instead. He repeated the change in both of his books containing the quotation. He leads readers to believe that the letter must tell the story of two noble Confederate men, trying to sink a federal warship, editing the deaths of the enslaved men out of history.*

The Pioneer was reportedly scuttled. The fall of New Orleans in late April 1862 meant that the Union was in charge of the city, and Hunley, McClintock, and Watson were afraid their own technology would be used against them. On May 13, 1862, Union troops arrested Charles Leeds, the owner of the foundry where the Confederacy had been manufacturing cannons and where the group had worked on their submarines. Shortly after this arrest, the three submariners decided it was time to move on. McClintock later stated that they had sunk their boat before heading for the nearest major Confederate port: Mobile, Alabama.

Newly housed in the Parks and Lyons machine shop in Mobile, Alabama, the trio got back to work. Their next design was dubbed the American Diver, but McClintock’s original plans and drawings of the vessel were lost long ago, and only general descriptions remain. He made some attempts to build the boat with either electric or steam power, but he ultimately abandoned both new ideas and returned to the hand crank.

However, this vessel actually got a real trial run. The little Diver traveled successfully throughout Mobile Bay, but the man she was showing off for, Confederate admiral Franklin Buchanan, was unimpressed. The slow speed of the vessel coupled with the fact that she later sank and nearly killed her entire crew meant that he politely recorded the entire affair as “impracticable.” In 1852 the US Navy had rejected the advances of poor submarine inventor Lodner Phillips with the simple line “The boats used by the Navy go on and not under the water,” and in 1863 the Confederate Navy was still not interested.

After the loss of the American Diver, Hunley, McClintock, and Watson rallied the support of even more financial backers and set out to create what would become their most famous design: the submarine that history would eventually remember as the HL Hunley. They dubbed it Fish Boat.

True to McClintock’s steamboat roots, the Fish Boat was hammered out of multiple wrought-iron plates, thought to have come from the boiler of a steamship. The new design reflected the lessons learned from the previous fish boats: It had glass deadlights to let light into the hull, and it had windows in the raised conning towers that a pilot could use for navigation. She was more stable too, with tall, wedge-shaped bow and stern pieces that ameliorated the “dirt dart” plummeting behavior of the CSS Pioneer.

McClintock would later declare that he had no knowledge of the submersible boats built in the centuries before him, but his work inarguably showed that he and the other inventors were all evolving toward the same basic physical principles for a working submarine. Like the submarine Turtle, built by David Bushnell in 1776, the Fish Boat used a simple but reliable hand crank connected to an external propeller. Like the cigar-shaped submarines built by Lodner Phillips in 1852, the Fish Boat had a long, sleek shape that was both stable and hydrodynamic. And even though historical documents indicate the Fish Boat was originally designed to tow a torpedo behind her on a lanyard, the constant fights between this lanyard and her spinning propeller meant that she would eventually be modified to transport her weapon on a spar attached to her bow, like Robert Fulton’s submarine Nautilus in 1801.

On July 31, 1863, the newest submarine finally managed to impress cantankerous old Admiral Buchanan. She towed a black powder torpedo on a rope behind her, dove beneath a barge placed in a river specifically for her trial, and reappeared about 400 yards on the other side of the shattered sacrifice. Buchanan promptly wrote of the victory to his colleagues in Charleston, South Carolina, advertising the sensational Fish Boat as the perfect way for them to destroy the Union ironclads lurking in their harbor, blocking their access to supplies. So, at the beckoning of Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard, the submarine was loaded on a train and shipped from Mobile to beleaguered and battered Charleston, the largest Southern city that still remained under Confederate control.

The Fish Boat never received her commission; she therefore never carried the label “CSS,” even later, after she was renamed the HL Hunley. At the time she arrived in Charleston, she was still civilian-owned and operated by the partners who built her. The partners, familiar with the history of her design iterations and their multiple sinkings, approached her operations in Charleston with a level of caution and risk aversion that the military men found unacceptable. They wanted the blockade lifted, and they wanted it lifted quickly. The Confederate Army lost patience, seized the vessel, and staffed her with a crew from the Confederate Navy, dashing Horace Hunley’s hopes of bounty and fortune. Unfortunately, despite the change in command, the luck of the Fish Boat’s predecessors had traveled with her from Alabama.

Serving as crew on the Fish Boat came with perks, specifically higher pay and more notoriety about town. The public demonstrations with the little vessel had ensured the crew was well known, especially among the other soldiers and sailors.

On one average day, Lt. John Payne stood with his head and torso up out of the boat, ready to begin such a demonstration. His crew was waiting for him inside the boat, ready to crank but relaxing for the moment. They were under tow, hatches open and breathing fresh air, with the CSS Etowah (sometimes referred to as the CSS Etiwan) doing the work for them until they got to the site of the demonstration. Payne just needed to free the towline then lower himself down into the vessel, sealing the conning-tower hatch behind him. The plan was the same as the plan for all the previous dog and pony shows: Dive under some obstacle, resurface on the other side, accept applause from the adoring and hopeful populace who wanted the blockade broken so very badly.

Rocky waves were making the job difficult, however, and the towline was a disaster. Payne struggled, trying to free himself from the line, but he slipped. Jammed partly inside the conning tower but still partly outside the hatch, his legs scrabbling for purchase accidentally knocked the long lever that controlled the dive planes. The narrow fins on the port and starboard sides angled in response, and the Fish Boat dove. The submarine sank, unsealed, beneath the surface. Water began to pour in through the open conning-tower hatches.

Payne managed to get himself fully out via the fore conning tower, and crewman William Robinson squeezed out of the conning tower near the stern. In order to escape the flooding metal cylinder, the men in the middle would need to slither through a deadly obstacle course. The twisting, circuitous pipes of the crank formed a broad spiral down the starboard side of the 4-foot-wide tube, and the long pine crew bench shrank the available vertical space on the port side. Each man was wedged in place, head and shoulders slouched to fit in the narrow hull, with his legs crammed between the bench and the crank, his arms pressed between the shoulders of his neighbors. The tiny deadlights overhead let in some sun, but the small circles of imperfect old-fashioned glass could only dimly light the interior of the trap. To escape, each man would need to keep calm in the dark, keep his head above the rapidly rising water, thread between the crank and the bench, stay hunched over inside the narrow hull, avoid the ballast blocks placed throughout the bilge, and find his way to the small target of a conning tower. Even then, they could only exit one at a time, unable to begin the process before their neighbors gave them space to move. Meanwhile, the ocean kept gushing in as the boat continued to plummet.

Crewman Charles Hasker was seated second in the single-file row of people inside the boat, and he took immediate action. Fighting against the torrent of water flooding through the open forward conning tower, he clambered over the bars and levers that controlled the boat, only to get halfway out of the hatch before the door slammed shut on his back. He worked his way out while she continued to descend through the water, until only his left leg remained trapped. As the submarine finally settled with a thud against the rough ocean bottom, the hatch door was jostled open and Hasker escaped for the surface.

Five men couldn’t make it. They died wedged in the jam-packed labyrinth between the bench and the crank. When the submarine was recovered, their corpses were “so swollen and so offensive” from their days in the warm summer seawater that they needed to be dismembered before they could be removed in pieces through the narrow ovals of the conning towers they had been trying to reach.

Some accounts differ in the details, stating that instead a wave swamped the open hatch door, but these accounts are generally suspected to be polite alterations of the truth to spare Payne’s pride. Whatever the true cause of the flooding, Lieutenant Payne was required to arrange for the purchase of coffins for his drowned crew, and to write a letter to his superior officer justifying the expense of extra-large sizes to fit the bloated bodies.

The five men of this first lost crew were exhumed in 1999 because their bodies had been mistakenly paved over to build a new parking lot for the football stadium of the Citadel, the Charleston military college. It took months to find the grave of the fifth drowned crewman, Absolum Williams, because the free, black nineteen-year-old grandson of a slave was not buried in the same resting place as his white crewmates. Beneath the thick layer of pavement, the discovery of telltale custom-dimensioned coffins and dismembered bodies confirmed the long-standing story of Payne’s unfortunate accident. The limbs of the men were placed next to their torsos and heads, and the extra-large coffins were hastily stacked one on top of another, two to a grave. The hands of several crewmen were inexplicably missing, and were never found.

A mere sixteen days after the accident, the Fish Boat had been recovered, cleaned, and assigned once more to Lt. John Payne. Five days after that, Horace Hunley audaciously suggested in a direct letter to Beauregard that he should personally be the one to lead the next crew. Beauregard agreed.

Hunley enlisted a group of eight volunteers, with Lt. George E. Dixon at the helm of his ship. The crew began to practice, again making repeated dives underneath ships, often towing a dummy torpedo behind them on a long line. One day, for an unknown reason, Hunley decided it was his turn. Seven men crawled into the boat to take the crank, and Hunley assumed the tiny wooden pilot’s bench beneath the forward conning tower.

The submarine was seen approaching the CSS Indian Chief, a favorite practice target. As usual, it was seen to dive below the surface of the water. However, this time, the submarine never reappeared. Unfamiliar with the controls and unpracticed in the boat’s operations, the proud Horace Hunley had plowed her nose-first into the ocean floor. Unable to raise the boat, he and the rest of the crew asphyxiated inside.

When the vessel was raised, the ghastly remains of the men were found huddled in anguish. They had tried to undo the bolts inside the keel that would have released the weights and sent the boat to the surface, but they did not finish in time. Hunley himself, doubtless panting and feeling the anxiety of the building carbon dioxide, was found curled tightly inside the forward conning tower, apparently trying to bash his way through the hatch door. With three Rachels of force pushing the small oval door closed, Hunley did not think to equalize the pressure like Wilhelm Bauer did. The hatch remained firmly sealed.

The stories of the sinkings have been muddled by time, the spread of rumors, and faulty human memory. As a result, historical documents report at least six separate stories about alleged sinkings in Charleston Harbor with up to fifty fatalities, but many seem to be exaggerations and variations on the same events. The general consensus among historians is that the Fish Boat sank twice in the summer and fall of 1863, killing a total of thirteen men. These fatalities earned her the nickname “the peripatetic coffin.”

Despite her horrid track record of killing her crew, one of the most common statements made in the modern press about the Hunley is that she was “ahead of her time.” I respectfully disagree. I think we underestimate “her time.” By 1862, James Clerk Maxwell had published his ingenious set of mathematical equations to describe the complex relationships between electricity and magnetism. The first practical refrigeration units were a cool twenty-plus years old (sorry, I had to), grain elevators and steam-powered locomotives were in everyday use, and electricity was becoming common enough that the circuit breaker had already been invented. The Americans of the 1860s may not have had cars and plasma TVs, but they had already witnessed more advanced technological innovations than we tend to give them credit for.

Many people mistakenly believe that the only way for a design to be noteworthy is for it to be complex and “ahead of [its] time.” For an engineer, a cleanly built machine that simply fulfills its purpose has a profound, inherent elegance and beauty. The hyperbaric chamber, a straightforward metal ball that holds gas, has this beauty. The Hunley, a tube with a basic hand crank and gears, has it too. Non-engineers tend to overlook these devices, ignoring them because they are not impressively elaborate, so it is easy to forget they exist. Even though it was unsafe, the Hunley, like almost every machine built by a good engineer, perfectly reflects the intersection of purpose, budget, timeline, and available materials. For that reason it has its own notability. McClintock made periodic deviations into new innovations like electric motors, but eventually he gravitated back to the robust, proven design parameters that he could get to function reliably on his urgent schedule: muscle power, a propeller, and one big-ass black powder bomb.

That is why she was ultimately the first submarine to be successful in combat. Her simplicity of design but complexity of story is why I was fascinated by her, despite the dark and devastating aspects of her history. That is why, after my study on suffocation was complete, I wanted to keep working on this problem. I needed to know why she failed, not in combat, but as a machine fails.

I stared down at the poor-quality black-and-white printout in my hand. It was my way of tempting Dale, of getting permission to work on this problem more. Dale was a scientist too, and the best way to intrigue him was by offering him mental candy in the form of a testable mystery. The printout was a screen shot of the Hunley’s conning tower, and it showed a fractured section that, according to the Friends of the Hunley, may have been broken by the bullets fired by the crew of the Housatonic in a last-ditch effort to defend their ship. The lucky-shot theory stated that the submarine then flooded through this broken chunk, drowning the crew.

It looked somehow wrong to me. The chunk missing was massive, and cleanly broken at the edges. Most of my knowledge of bullets was either as a navy civilian living in the gun culture of the deep South or as an injury biomechanist; therefore, most of my personal understanding of terminal ballistics at that time focused on how bullets ripped and tore through paper targets, mounds of red Southern dirt, or people. Both paper and people tear much differently than cast iron does, but still, my sneaking hunch was that the damage looked far too large for a Civil War round, with not enough tearing at the edges.

I was sitting in our lab’s weekly meeting, holding this piece of paper and waiting for my turn to speak. Once a week, at the appointed time, we would hear Dale’s boots thunk their way toward the shared departmental conference room at the end of the hallway. The noise signaled the beginning of our meeting, when the nine of us who carried the title of “graduate student” were expected to sit around the long wooden table and inform Dale of our progress.

I loved lab meeting. I thought it was thrilling. We would each take our turn talking while Dale clicked away at his laptop either taking notes or (for all we knew) doing something entirely unrelated. Each student reported their progress, their problems, their new victories, and their frustrations. The purpose of lab meeting was to help one another when we got stuck, and to share in the quiet, cathartic feeling of victory that comes with each new piece of data that signifies a tiny scientific step forward into undiscovered knowledge. We learned from one another, and even if we had nothing in common outside of science, my lab mates and I had the deep, common roots of curiosity and endless questions about the world. These were the shared traits that had brought us all into graduate school and into that meeting.

I passed my printout down the human chain of my lab mates to Dale at the far end of the table while explaining the lucky-shot theory. I had outlined in my head a careful plan to test the plausibility of the theory with minimal expense: Do the math to see how long the Hunley needed to drift before she sank in the location where she was found. Do the math to see how quickly she would sink with holes of different sizes. Create complex three-dimensional models of both the bullet and the conning tower, then run dozens if not hundreds of simulations to test various ways they could crash into each other, each time making small but critical changes to numerous variables like the material properties and the velocity of the bullet. The first two tasks I knew I could handle, but the last one was intimidating.

Dale began to slowly shake his head at me. Letting out a single bark of a laugh to interrupt the rapid flow of my words, he declared my new plan.

“Rachel,” he said. “Buy some cast iron . . . and shoot it.”

He passed my printout back. I loved lab meeting, but some were better than others.