‘I hold that the brain is the most powerful organ in the human body.’

Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease (400 BCE)1

THE YOUNG WOMAN, waiting somewhat apprehensively in the brain-scanning department, was blonde, smartly dressed and obese. She was one of thirty-five volunteers taking part in a study conducted by psychologist Lauri Tapio Nummenmaa, from Finland’s Aalto University School of Science. Nineteen of the women were significantly overweight, with an average BMI of 44, while sixteen were slender with an average BMI of 24. What Nummenmaa and his colleagues wanted to discover was whether their brains responded differently to images of food.2

As we explained in Chapter 2, we live in an increasingly obesogenic world – an environment in which there is both an abundance of palatable, often low-cost, food and a multitude of powerfully evocative ‘food cues’. Yet, while almost everyone is exposed to these enticements to look at food, smell food, taste food, eat food and think about food, not everyone has a weight problem and currently only a minority are obese. This raises the question of how and why a majority, albeit a decreasing one, are able to remain slim. The answer, many researchers believe, is to be found in the way food cues, in their various guises, are processed by the brain. Using brain-imaging techniques they are gradually casting new light on the differences between the brains of individuals of normal weight and the obese.

In this chapter, we will examine various aspects of eating motivation, and try to provide some insight into the differences between eating to satisfy physiological need (what scientists refer to as ‘homeostatic’ motivation) and eating for pleasure (what is referred to as ‘hedonic’ motivation). Since obesity can largely be attributed to eating for pleasure, as opposed to need, a clear understanding of hedonic motivation is necessary in order to understand obesity.

We owe a great deal of what we know in this regard to brain scanning technology, such as the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) used in Dr Nummenmaa’s investigation. Using this kind of equipment we are beginning to tease out the differences between an obese person’s brain compared to a lean person’s.

A white-coated technician helps the young volunteer onto the ‘patient table’ of a two-million-dollar magnetic resonance imaging scanner – it is a human-sized tunnel surrounded by a large and extremely powerful magnet.

A pillow is placed under the volunteer’s knees, to ensure her back remains as flat as possible during the scan, and a white plastic frame is positioned around her head to restrict neck movements. Finally she is handed a ‘panic button’ with which to summon help if necessary. The technician clicks a switch and the volunteer slides silently into the dark belly of the doughnut-shaped machine. This done, she retreats to the safety of the control room – so powerful is the scanner’s magnetic field that, while it is in operation, only the person being scanned is permitted to remain.

The scanner works in the following way: as neurons become more active, their energy consumption increases and they require additional oxygen. This is transported around the body by haemoglobin, a blood protein, which comes in two forms, oxygenated and deoxygenated. When the blood flow to the brain changes, the concentrations of oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin in the blood also change, as oxygen is directed to the areas within the brain that demand it most. It is this Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent activity (BOLD) which fMRI measures. This varies between individuals; for those individuals who show hypersensitivity to food reward, an image of a chocolate cake alone will cause more blood to flow to the brainstem and areas that are responsible for motivating behaviour.3

Over a period of forty-five minutes, the machine will take a sequence of thirty images, each depicting a 4-mm thick slice of the volunteer’s brain. At the same time she will be shown a variety of colour photographs depicting different types of food. Some will be mouthwateringly delicious treats, such as cakes, pizzas, and strawberries dipped in chocolate. Others will be blander fare like lentils, cabbage and crackers. Despite the fact that for technical reasons no actual food can be sampled, the researchers believe the photographs alone will be sufficient to identify differences in the way the brains of the obese and lean women will respond to the ‘anticipatory’ rewards they offer.

One important limitation with fMRI is that the timing of any increase in neural activity cannot be determined with any great accuracy. While the scientists can say with precision where in the brain the response occurred, they are unable to state precisely when.

Despite this constraint, in a crude sense, MRI and fMRI provide a biological map for detecting human motivation. Increased blood flow to a particular area in response to a stimulus is a measurable physiological change which depicts a psychological phenomenon. If, for example, a subject was shown an image of a delicious foodstuff, greater blood flow to areas of the brain associated with motivation would signify a greater drive to obtain that foodstuff. Measuring blood flow in this way allows scientists to study which stimuli cause the biggest changes in the brain, and to compare the reactions that different individuals (such as obese and lean individuals) have to the same stimuli.4

We will return to Dr Nummenmaa’s important and revealing study in due course. But first let’s look at some of the areas of the brain which play key roles in determining how much we eat, either because they are concerned with our survival, or because they are concerned with pleasure.

About the size of a large cashew nut, the hypothalamus is located deep within the brain, just above the brainstem. The hypothalamus could be called the body’s thermostat; its function is to maintain homeostatic balance (balance of the body’s systems) by coordinating and integrating activities of both the nervous and endocrine system. In this way, the hypothalamus is responsible for regulating blood pressure, body temperature, circadian rhythm, heart rate, immune response, sexual desire, thirst, water balance and, most especially, hunger.

Since it is intimately involved with so many crucial functions of the body, including hunger, scientists initially believed failure of hypothalamic functioning to be the major culprit in the obesity crisis. In fact, years of research have shown that it isn’t quite that simple: the hypothalamus is but one part of the complex interplay of biological systems relating to our need and love for food. However, it does still have a crucial role to play.

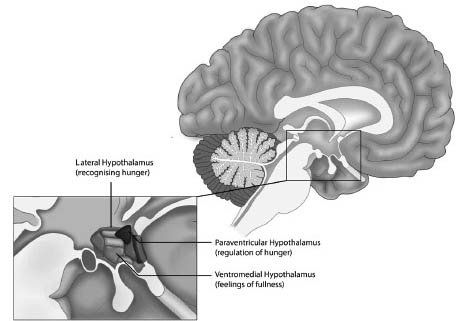

In general, three areas of the hypothalamus are associated with hunger and eating motivation, and are shown in Figure 7.3. They are:

1) The lateral hypothalamus, associated with recognising that we are hungry.

2) The ventromedial hypothalamus, associated with feelings of fullness and satiety.

3) The paraventricular hypothalamus, associated with regulation of hunger.

Homeostatic control over the amount of food we eat involves physiological processes that determine when we start and stop feeling hungry, and which suppress hunger pangs between meals, thereby regulating body weight. The average adult gains around 0.5 kg per year, which is about a 3,500 kcal surplus. Given that we eat about 900,000 kcal per year, this represents only a 0.5% discrepancy, demonstrating that the hypothalamus actually does a fairly accurate job of keeping us in homeostatic balance.5 We are therefore left to wonder how people become obese, and what drives the desire to eat excessively.

Early studies of obesity were based on the belief that an individual’s weight depends on a genetically determined metabolic ‘set point’.6 The theory is that our set point of hypothalamic control guides our eating behaviour at all times. This likens the relationship between our body and brain to a central heating thermostat; if the room temperature falls or rises above a predetermined level, then a thermostat turns the boiler on or off as required. According to set point theory, while weight gain is extremely unlikely to occur in individuals with a naturally low set point, for those unfortunate enough to have inherited a high set point, becoming overweight is unavoidable.

In a lot of ways this seems a sensible theory, as it does help explain why some individuals never seem to have much difficulty in regulating their body weight, while others do. However, it fails to take into account factors such as food choice, metabolic responses to diet, hormone levels, and environment. Moreover, the recent exponential rise in obesity demonstrates the fallacy of our belief that some people are simply ‘lucky’ with a genetically determined set point. Obesity reflects not only a person’s biology, but their environment too, otherwise we would not have seen obesity rates quadruple within the last forty years, across the globe.7

‘I can eat anything, no matter how fattening, and never put on a pound’ is an often repeated boast on the part of those lucky enough to be able to retain a slim figure without much effort. However, as the obesity crisis demonstrates, fewer and fewer people are able to maintain such a lean look. Moreover, a person’s perception is everything; ‘I can eat anything’ may be the case for someone who is thin, but they may only be consuming 1,200 kcal a day. For an obese person trying to diet, they may be overeating without knowing it. Thus, set point theory does not, in fact, provide a comprehensive picture of human weight.

Hypothalamic signalling plays an essential role in guiding our behaviour; it can be held to account for the sensation of when we are ‘absolutely starving’, the kind of hunger that strikes when we haven’t eaten for hours, or are in serious states of energy depletion. Yet, given how accurate the hypothalamus is at keeping us in homeostatic balance, it is clear that eating for pleasure, rather than metabolic need, must be an important component of the obesity crisis. Thus, it is important to look beyond the hypothalamus, to networks within the brain that are responsible for pleasure and reward.8

Located at the base of the forebrain, and a few millimetres away from the hypothalamus, is a region sometimes dubbed the ‘reptilian brain’, due to the fact that it is the most basic or primitive part of the whole brain.9 More correctly identified as the basal ganglia (Figure 7.4), this area actually consists of several distinct regions, the largest of which are the caudate nucleus, putamen and globus pallidus. Present in pairs, with one located in each of the brain’s two hemispheres, they are known collectively as the striatum, or ‘striped body.’

Shaped somewhat like the letter ‘C’, the caudate nucleus has a wide head tapering into a thin tail that curves towards the occipital lobe at the back of the brain (which is responsible for vision). The caudate conveys messages to the frontal lobe, especially to an area just above the eyes known as the orbitofrontal cortex (which we will discuss in more detail shortly). It plays an important role in learning, storing memory, the development and use of language, falling asleep, social behaviour and voluntary movement. Recent research has shown that it responds differently to food in lean individuals than in obese individuals.10

The putamen (from the Latin meaning ‘shell’) is located beneath and behind the front of the caudate. It is involved with two forms of learning: implicit and reinforcement. The former occurs when people acquire knowledge through exposure, for instance by watching TV or studying a textbook. Reinforcement learning involves interacting with the environment and discovering which actions produce the best and most consistently rewarding outcomes. As we will explain later in the chapter, this type of learning plays a significant role in the development of obesity, as obese people may be more vulnerable to the rewarding effects of food. As we describe later in the chapter, eating is a hugely pleasurable experience. Consumption of foods, particularly those high in sugar and fat, elicits a cascade of neurochemical reactions, such as the stimulation of the endogenous opioid, serotonergic, and cannabinoid systems in the brain. All of which are associated with the wonderful, yet fleeting, sensation of eating.11

The globus pallidus (Latin: ‘pale globe’) is located inside the putamen and receives inputs from the caudate and putamen. It sends messages to an area of the brain called the substantia nigra (black substance) which is where dopamine is produced. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter which can produce intensely pleasurable feelings – because of this it is a key player in the brain’s reward system, as we shall see in a moment.

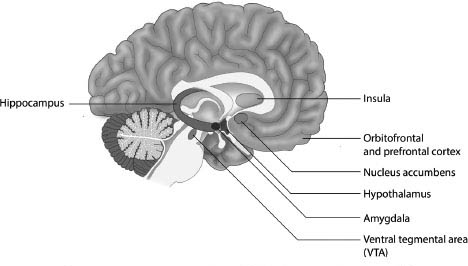

In addition to the hypothalamus and the basal ganglia, there are other parts of the brain involved in eating and overeating, including the amygdala (stress and emotions), insula (sensory integration), and the nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area (VTA), orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortex (rewards and self-control).12 These are shown in Figure 7.2.

The brain has two amygdalas (Greek for almonds, which they resemble in shape and size), one in each hemisphere, which are involved in processing rewards, the desire to eat and detecting the intensity of flavour. They also play a crucial role in stress and anxiety disorders. This is a topic we will deal with in greater detail in Chapter 9 when we discuss the part played by stress and anxiety in overeating.13

The hippocampus (Greek for seahorse, named for its resemblance to that animal) is a part of the brain involved in storing memories. It enables us to rapidly recall foods we found pleasurable and rewarding, or those we found unpleasant and would prefer to avoid. Early eating memories can therefore play a key role in determining our tastes and preferences as adults. If, as a child, we came to regard vegetables as disagreeable, for example, this memory is likely to dissuade us from eating them for the remainder of our life.14

Another important region is the oval-shaped insula, also known as the Island of Reil. It is essential in determining human behaviour, coordinating autonomic or unconscious bodily functions, in addition to emotional responses.15 Neuroimaging studies suggest it has anatomically distinct regions, which are concerned with different aspects of taste perception. One part, for example, responds to taste intensity, irrespective of how the diner feels about what is being eaten or drunk, while another mediates emotional responses to the taste.16

Interestingly, obese individuals show increased activation in both regions during consumption of food compared to lean individuals, suggesting that they may perceive greater taste intensity as well as experience an increased emotional sensation of reward.17

The nucleus accumbens is a part of the brain which becomes especially active whenever people experience intense pleasure, especially from food or sex. It receives information from, and sends signals to, a collection of neurons located on the floor of the midbrain close to the midline; this area is called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and is involved with thinking, motivation, and the powerful emotions associated with falling in love and experiencing orgasm. On the darker side it plays a role in drug addiction and several psychiatric disorders. It releases dopamine whenever something happens which predicts an immediate reward.18

Imagine, for example, that while gazing through the window of a patisserie you notice a mouth-watering cream cake on a display stand on the other side of the glass. And it’s the last one in the shop! Anticipating your purchase of that delicious treat, your VTA sends a flood of dopamine coursing through your brain.

Now imagine that as you push open the shop door, the sales assistant hands the cake to another customer. Your desires have been frustrated! You are likely experiencing the sensation of disappointment, and kicking yourself for not acting faster. In such a case it could be argued that the decline in dopamine levels is a response to the over-prediction (and under-delivery) of the cream cake reward. If, however, you purchased and enjoyed the cream cake, an action that met your expectations, then the abrupt dopamine spike would have signalled the under-prediction (and over-delivery) of a reward. If the cake was exceptionally delicious, high in sugar and fat, an even greater sensation of pleasure would ensue. However, if the cake had gone bad, and the cream was spoiled, your reaction would be one of disgust.

This highlights the basic mechanisms by which we learn about food; sensations of reward and punishment are rudimentary Pavlovian mechanisms that shape our behaviour. By understanding this concept, and viewing food in terms of how it ‘rewards’ or ‘punishes’ the senses, we can glean greater appreciation of our own relationship with it. Some foods are immediately rewarding, yet have no nutritional value; the high fat salt/sweet taste coaxes our brain into an immediate state of bliss, yet the food does very little for our body. However, some foods that are hugely nutritious taste much less exciting, such as vegetables. Their less sweet, and sometimes slightly bitter taste is something that requires learning and experience to appreciate, yet once this pattern is established one can ‘learn’ to crave healthy food. The key lies in ensuring the learning phase occurs early, so an individual can reap the benefits of healthy eating habits throughout their entire life, as opposed to having to work to change their food preferences later in life.

Thus for individuals vulnerable to the rewarding effect of food, the constant reminders of it in the modern world, such as ubiquitous advertising, can drive them to constantly search out the rewards they predict from such food cues. This is, in part, what we mean when we say that the world today is an obesogenic environment. In Chapter 11 we will further discuss the powerful role of these cues in the obesity pandemic.

For many years researchers believed obesity reflected hypothalamic dysfunction; however, we now know the essential role that pleasure plays in overeating. Since pleasure circuitry runs throughout the entire brain, and not just within the brainstem, it is likely to have a greater influence on shaping behaviour. Beginning from the nucleus accumbens and extending into the frontal regions of the cortex, overeating cannot solely be attributed to one area within the brain, and is thus a significantly more complex problem to tackle.

While the hypothalamus acts to sense general levels of energy within the body, and the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental areas act as ‘hedonic hotspots’ concerned with pleasure, an outer region of the brain located just above the eyes, the orbitofrontal cortex, is involved in detecting how ‘pleasant’ a food is and controlling decisions about whether or not to eat it.19 A study also found that women who fasted were more vulnerable to food-related cues, showing greater activity in frontal areas of the brain that translated to cravings and memories of food in fasting patients.20

Finally, there is the prefrontal cortex, which is located just behind the forehead and is the last part of the brain to mature. This is responsible for self-control, judgement and caution and plays a vital role in inhibiting impulsive eating.

Hopefully this whistle-stop tour of various areas of the brain has helped to give a sense of what a complex interplay between the different areas is involved in why and how we eat. There are no completely straightforward answers; rather, neuroscience and technology have allowed a deeper understanding of the networks within the brain, and how they interact with environmental and internal factors to guide ‘pleasure-based’ decisions to eat.

Dopamine (which also goes by the name 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neurotransmitter which is released from nerve cells in the brain’s substantia nigra and ventral tegmental regions, whenever we are engaged in, or anticipate, a pleasurable activity. Dopamine plays a central role in learning and memory, as the larger the release of dopamine is with any given activity, the higher the probability we will remember and repeat that behaviour. Research has shown that dopamine released in the nucleus accumbens is directly implicated in addiction.21 When it comes to food, enjoying a delicious snack or even just anticipating consuming one, can trigger a tsunami of dopamine which ‘hijacks’ the reward circuitry of the brain to produce an intensely rewarding experience.

In order for any neurotransmitter that has been produced and released by a nerve cell to affect another, it must first ‘lock on’ to receptors in it. It is here that one of the main differences between the brains of lean and obese individuals may be found; studies have shown that overweight individuals have fewer dopamine receptors than those who are lean.22 In essence this is because when the dopamine receptors are overstimulated, the brain reacts by pruning them.

Scientists gained an appreciation of the dysfunction of dopaminergic circuitry through the study of addictive behaviour and use of illicit drugs. Through years of addiction-based research, scientists have learned how drugs (particularly amphetamines and stimulants) lead to a surge in dopaminergic activity (which can in turn lead to the pruning of receptors). In more recent years, however, we have learned this can occur with a variety of other substances (including food) and also with behaviours (such as shopping or gambling). For this reason, our definition and understanding of addiction has changed; we are now beginning to view a variety of behaviours as having the potential to be addictive, including eating and overeating.

Researchers believe that once the receptors are pruned, or in scientific jargon ‘down-regulated’, the individual must consume more of the reward (such as food) to achieve the same amount of pleasure on a subsequent occasion. The ‘dose’ of food must be stepped up. But more stimulation leads to more receptor depletion, obliging a further increase in the stimulus and meaning that yet more of the reward is needed to achieve the same effect. An addiction of any kind involves this continuing need to achieve the same level of reward as it becomes ever harder to do so.

Neuropharmacologists Luca Pani and Gianluigi Gessa found that: ‘The dopaminergic system has remained identical for the last several centuries . . . external conditions which interfere with its physiology have dramatically changed.’23 In other words, the world in which dopamine developed as part of brain chemistry is vastly different from the one in which it exerts its effects today.

At the core of human nature lies the quest for survival. In order to enhance the probability of survival, we have evolved a pleasure system that reacts to behaviours that the brain and body believe, in order to help us live another day. However, this system can be fooled and abused in what researchers refer to as ‘hijacking’; certain behaviours which are pleasurable, such as taking drugs or overeating, actually limit life rather than sustain it. In response to this inbuilt desire for enjoyment, or the scientific term, ‘reward’, we have created tools, games, social structures, stimulants and foods that are designed to unleash pleasurable sensations. Two centuries ago, we had stricter boundaries regarding the number of friends we could have, the types of drugs we could take and the amount of food we could eat. Today, we’ve developed technologies and innovations which enable us to circumvent these boundaries.

For some, the drive for pleasure may develop into a pathological need to achieve dopamine’s rewarding high, even at the cost of health and wellbeing. Some foods today are specifically engineered to flood the brain’s reward centres with as much dopamine as possible, almost inevitably beginning the process of addiction we have described. Obesity demonstrates how exploiting our reward system via food can have disastrous consequences.

Over the last thirty years, researchers have also come to appreciate the hugely important role played by a tiny group of neurons in the hypothalamus, which were once dismissed as insignificant. It’s not hard to see why this was the case – there are only around 20,000 of them, compared to the brain’s total of approximately 80 billion neurons.

However, it has now been established that, despite their tiny numbers, they play a key role in a wide range of vital functions, ranging from regulating patterns of sleep and wakefulness, to the experience of pleasure and perception of pain. Their role in obesity demonstrates the tremendously complex interplay of chemical interactions that guide human behaviour and reveal how just a single, tiny deviation in normal brain activity can result in enormous problems for people in everyday life.

There is a particular neuropeptide related to this group of neurons. Neuropeptides communicate between neurons, and are one of the most primitive building blocks for establishing function within an organism. Therefore, they are also implicated in behaviour, as the communication between neurons ultimately leads to all of our actions, thoughts, and perception. This particular neuropeptide was discovered simultaneously by two independent groups and is therefore known as both ‘orexin’ and ‘hypocretin’.

Orexin neurons provide a crucial link between energy balance and the coordination of mood, reward, addiction and arousal. Dysregulation of this infinitesimally tiny brain region produces some terrifying physiological and psychological consequences. These include a tendency to fall asleep in the presence of stress or emotional arousal. Such ‘sleep attacks’, known as narcolepsy and cataplexy, can be as frustrating as they are dangerous. Narcoleptics may put their life in jeopardy falling into immediate deep sleep, resulting in injuries ranging from bruises to serious trauma. To add to their problems, narcoleptics are often overweight, even when they do not overeat.24 The laboratory mice whose orexin neurons have been removed exhibit late-onset obesity despite never being allowed to overeat. It therefore seems possible that even non-narcoleptic people could experience problems with orexin and the neurons associated with it that might result in weight issues.

While the fact that the neurons that deal with orexin are located in the hypothalamus is indicative of orexin’s role in guiding homeo statically driven hunger, their direct connection with the reward pathway, via the nucleus accumbens, suggests orexin could also be involved in hedonically driven eating. If so, it might be an important focus for trying to minimize the pleasurable feelings associated with either drug abuse, or overeating hyper palatable food.

One possible way in which the discovery of orexin might enable us to control obesity is through the development of an orexin receptor ‘antagonist’ – a drug that would block the uptake of orexin. In mice on a high-fat diet this has been found to suppress weight gain. It has been suggested such a drug could be useful for treating a wide range of conditions, from the withdrawal symptoms of drug addiction, to the management of pain or excessive stress.25

As we have seen, one critical difficulty with trying to create pharmacological intervention for obesity is the tremendous complexity of our brains and the interaction between hedonic and homeostatic systems. There is not one single area of the brain that must be targeted, but several. However, with the discovery of orexin, researchers may be getting closer to bridging certain gaps, and thereby to being able to treat the parts of the brain related to homeostatic and hedonic eating.

Let’s now return to the fMRI study we described at the start of this chapter. When Lauri Nummenmaa and his colleagues analysed the images taken of their subject’s brains, they found that when an individual was overweight their brain responded differently to images of food.

The reward centres in the brains of both lean and obese women showed greater activation when looking at images of appetising food, as opposed to images of bland food. However, importantly, the level of this activation differed between the two groups.

‘Responses to all foods (appetising and bland) were higher in obese than in normal-weight subjects,’ explains Nummenmaa. ‘When appetizing and bland foods were contrasted with each other, the caudate nucleus showed greater response in the obese subjects.’ The results suggest that obese individuals’ brains might constantly generate signals that promote eating even when the body does not require additional energy uptake.26

The response of the brains of obese people to food is characterised by an imbalance between those regions that promote reward-seeking and those involved in exercising self-control. Their brains are hypersensitive to the sight of food, which in a world replete with food cues is very bad news indeed!

In summary, obesity can be seen as the reflection of an imbalance between homeostatic signalling, reward signalling and inhibitory control within the brain. As people continue to put on weight, reward signalling becomes chemically disrupted, meaning that obese people start to have greater anticipatory response to food-related cues and imagery, which triggers the motivational cascade to engage in eating.

Lean individuals are able to limit eating in response to energy need; in essence, because their response to hypothalamic or homeostatic signalling is not overridden by acute sensitivity to food reward, they are able to ignore the external reminders prevalent in our environment that encourage overeating. For obese individuals, the pattern is not quite the same. There is a wealth of information that suggests obese people process food reward in a way that is distinct from lean individuals, and their biologically based heightened sensitivity to reward is likely the real culprit in disrupting eating motivation.

The overwhelming drive to pursue food reward, even at the risk of harming one’s health, has been compared by some researchers to drug addiction.27 Pinpointing why, precisely, some people are more vulnerable to the rewarding effects of food or other pleasurable activities has been the focal point in addiction-based research for decades. The first issue is that there is a heightened (hyper-) responsiveness to environmental cues that predict food; the second issue is that there may be hypo-responsiveness once food is actually consumed.

As we have seen, research has shown that, compared to lean individuals, overweight people show significantly greater anticipation prior to eating, yet it is not entirely clear whether obese individuals experience more pleasure while eating, or less.28 We do know that obese individuals have a marked preference for high-fat and high-sugar foods and consume more of them.29 Children with obese parents (who are therefore at a greater risk of obesity) also show a greater preference for the taste of high-fat, high-sugar foods and eat more avidly than children of lean parents.30

Several studies have reported that the obese show reduced levels of dopaminergic response to eating as compared to lean individuals.31 These findings have led some researchers to suggest that overweight people become increasingly hypo-responsive to rewards and continue overeating to compensate for this depletion.32 So the consumption of obese adults and children may in fact be tied to limited capacity to experience pleasure, which explains the desire to eat more in order to reach the ‘normal’ levels of pleasure enjoyed by lean people.

In our view, those at risk of becoming obese initially exhibit hyper-responsiveness in brain areas responsible for taste and touch. As a result, they anticipate their next meal more intensely and display greater sensitivity to food cues. However, as they start to put on weight, they develop a tolerance to the rewarding effects of food. This may be accompanied by a down regulation or ‘pruning’ of dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia. In response, the ‘pleasure pedal’ has then to be pushed down ever harder in order to achieve the same level of reward; in this case, more hyper-palatable food is needed to create the same sense of wellbeing and pleasure.

The idea follows similar models proposed for many other disorders of ‘hedonic excess’ – those disorders which relate to pleasurable substances or behaviours including gambling, shopping, sex addiction, or drug abuse. Yet obesity is unique, insofar as all systems in the body are implicated during the course of weight gain. It is not simply the brain, but also the body that contributes to the drive to overeat.

As we saw in Chapters 5 and 6, the obese person’s greater resistance to leptin and insulin contribute to the sensation of hunger, yet it is the quest for pleasure which dopamine is responsible for that leads to a perceived need for ever-larger quantities of energy-dense foods.

Increased sensitivity to reward renders the obese individual more vulnerable to food cues, which are rife in our modern food environment. Paired with a numbed response to actual food ingestion, a perfect storm arises. Overeating and continued weight gain is caused by the combination of a predilection for energy-dense foods, an environment where such desires can be easily satisfied, and the body’s inability to cope with this over-availability of fuel. It is a cycle from which it is extremely difficult – though not impossible – to escape.

‘As people become obese, they become insulin- and leptinresistant, thus removing the normal peripheral signals that help inhibit the rewarding effects of food; the more severe the obesity, the worse the brain becomes at preventing excess food intake’, explains Nora Volkow. ‘You don’t have a mechanism to counter the drive to eat . . . it’s like driving a car without brakes.’33