Introduction

The processing speed of the human sensory apparatus contributes to producing the impression that, in reading text or listening to speech, information uptake is nearly instantaneous and that the meanings of words and sentences are given to us as though they were part of the input. However, this impression is mistaken, as one can realize when reading a text or listening to a conversation in a foreign language. While we may be able to identify word boundaries in speech, aspects of words’ internal structure, and some syntactic constituents using word length or frequency cues, we would most probably fail to assign the intended meaning to the discourse. This suggests that language comprehension is rather a process that unfolds in time and that what are given as inputs are just visual or auditory signals. Meaning is internally generated by the brain.

The human capacity to recover the meaning of linguistic signals arises during cognitive development and may deteriorate as a result of traumata or disorders that may have neurological origins or implications. A healthy, developing brain is therefore necessary for us to learn, process, and produce meanings. The title of this book alludes to an internalist and materialist notion of meaning. Indeed, I believe meanings are in the brain. Semantic building blocks are stored inside our brains, and inside our brains is where these building blocks are put together. This is strictly a belief in presumptive materialism (van Fraassen, 2002), not in reductionism. We expect to discover some fundamental facts about meaning in particular regions of space-time (e.g., in the brain) by measuring and modeling certain physical events (e.g., neural activity). We do not expect to discover such facts by studying other physical events in other portions of space-time, such as sound waves propagating through air in the space between two people engaged in a meaningful conversation. We may expect that technological breakthroughs will grant us access to new empirical domains, exactly as brain imaging did just a few decades ago, and that those empirical domains will disclose fundamental facts about meaning. However, we assume that those empirical domains would still be part of the physical world. This is presumptive materialism.

Reductionism is the idea that all our knowledge of facts concerning meaning, including the generalizations put forward by logic, linguistics, and philosophy, may be derived from our knowledge of the more fundamental facts we discover within the physical world. This is an epistemological thesis—note the emphasis on knowledge of facts—which should be distinguished from the ontological thesis that facts about meaning are grounded in facts about the brain.1 Neither thesis entails presumptive materialism, but the ontological thesis is much more plausible and compatible with it. The kinds of facts that neuroscience discovers are ontologically more fundamental than the facts discovered by semantics: the former underpin the latter—no brains, no meaning. The epistemological thesis must be exactly reversed, though. The knowledge produced by semantics (e.g., in logic, linguistics, or philosophy) is epistemologically more fundamental than knowledge produced by human cognitive neuroscience: the former enables the latter—no semantics, no neuroscience. Research on meaning tends to progress from the less fundamental (the mind) to the more fundamental (the brain), thus knowledge of less fundamental facts is used to generate, through technologies of various kinds, knowledge of more fundamental facts.2 This is the approach adopted in this book and explained in greater detail in what follows.

Are Meanings in the Brain?

A neuroscience of meaning rests on logical and philosophical assumptions that determine its structure and goals. If one of those assumptions is that meanings are “in the brain,” as required by internalism, showing they are not would seem to put a neuroscience of meaning on a rather insecure foundation. The classical Twin Earth argument by Putnam (1973, 1975) is designed to challenge the idea that meanings are functions of cognitive states. Imagine two parallel universes, at a time in which chemical knowledge and observation are unavailable. In one universe, containing us and Earth, water is H2O. The other universe is identical to the first but contains a Twin Earth, inhabited by twin versions of us, in which what is called ‘water’ is a different molecule, say XYZ. Suppose that H2O and XYZ are identical in appearance and use. Speakers on Earth and on Twin Earth may share the same perceptual and cognitive states when they talk about water. Yet, ‘water’ would still refer to a different substance in each universe: H2O and XYZ, respectively. Putnam’s argument is taken to show that meaning is not “in the head” and so is not susceptible to experimental and computational analyses of the kind performed in neuroscience.

Upon closer examination, this clever and powerful argument says more about theoretical notions of “meaning” than it says about where meanings reside. Let us analyze Putnam’s reasoning by using standard tools. Frege (1892) famously argued that one should distinguish the Sinn (sense or intension) of expressions from their Bedeutung (denotation, reference, or extension).3 He noted that one can use different expressions, like ‘Hesperus’ and ‘Phosphorus,’ resulting from different conceptualizations, to think and talk about the same object: the planet Venus. Here, two senses correspond to one denotation, while in the Twin Earth argument, it would seem that a single sense of the term ‘water’ is related to two different denotations—H2O and XYZ. The argument succeeds in showing that (a) meanings qua denotations are not “in the head” and that (b) cognitive states cannot determine what expressions denote.

However, there is an alternative reading of the Twin Earth argument, in which meanings qua senses are not cognitive states. Here, the key issue is whether we accept or reject the prospect that ‘water’ has the same intension on Twin Earth as on Earth. If we accept that, it follows from the Twin Earth argument that the sense of a term does not determine its denotation. But this would subvert a core tenet of logical semantics, namely that “sameness of intension entails sameness of extension.” If instead we concede that ‘water’ may have different intensions on Earth and Twin Earth, it follows from Putnam’s argument that intensions are not cognitive states, as those should be identical in the two universes. Putnam’s case entails that these two requirements—that intensions determine extensions and that intensions are “in the head”—cannot be jointly satisfied by any theory of meaning.4 Twin Earth warns us that internalism may become indefensible if meanings are identified with senses or intensions, classically understood. This also shows that a neuroscience of meaning requires a dynamic epistemological foundation, in which theories of semantics may undergo selection and revision. This book pursues that kind of “critical approach” to semantics as a foundation for a cognitive neuroscience of meaning.

The road to a well-reasoned internalism has numerous twists and turns. First, one should determine what exactly is not “in the head.” Physically, there exists a universe of entities and events utterly independent of the mind. However, one could ask whether it is external reality that natural language refers to or instead an internal representation of external reality (Jackendoff, 2002). Believing that the human brain entertains direct semantic relations with reality seems nothing short of believing in magic. Semantic relations are grounded in causal relations of two types:5 (a) connections between physical events and the brain, mediated by sensation and learning, and resulting in neural representations of reality; (b) functional connections between neural representations of reality and language in the brain.6 These functional connections are the subject of this book. Their structure varies considerably, but our aim here is to uncover the invariants, both anatomical and physiological, that enable and govern those functional links. In addition, the aim is to show in what sense exactly those functional relations are causal relations, that is, how they arise from patterns of currents flowing from one brain region to others through known anatomical connections.

Second, one must establish how much is “in the head.” In Putnam’s analysis, extensions are outside the mind and are linked to intensions by external forces:

The “average” speaker who acquires [a term] does not acquire anything that fixes its extension. […] his individual psychological state certainly does not fix its extension; it is only the sociolinguistic state of the collective linguistic body to which the speaker belongs that fixes the extension. (Putnam, 1975, p. 229)

Putnam’s reference to a linguistic community, as opposed to mind-independent states of the world, potentially entails a return to mental content. There appears to be no way for a community of speakers to “fix” the terms’ extensions, unless there are individuals who decide or discover what terms refer to (e.g., that H2O is ‘water’) and unless this information is shared with the linguistic community. Brain states are causally linked to states of the world, so that typically we know (as individuals) and share (as a community) the extensions of the terms we use in ordinary discourse. When we do not know, we may turn to experts to realign our epistemic states with the actual term extensions (Fodor, 1995). It is unclear exactly what sort of “sociolinguistic states” could possibly fix the extensions of terms while being entirely ungrounded in mental content. It seems more likely that any given state of a “collective linguistic body” is a reflection of aggregate or invariant properties of the internal states of individual speakers and learners. “In the head” are not just the internal states associated with the use of linguistic expressions but also states supporting the construction, discovery, learning, and cultural transmission of facts about language and the world. Surely, this would not satisfy Putnam or the externalist because none of this would “fix” reference in the desired sense. However, it may comfort the internalist, as it demonstrates that the scope of a theory of meaning in the brain could be quite broad, perhaps broader than the scope of a theory of meaning as such.

The philosophical challenge for a theory of meaning in the brain is to endorse internalism without cutting off meaning from reality. As pursued in this book, internalism is the idea that linguistic meanings are functional relations between neural representations of language and neural representations of reality. These representations do the work of the sense (intensions) and reference (extensions) of expressions. Some such representations are anchored to reality via sensation and (cultural) learning. That is how we can know that ‘water’ means water and that water is H2O. Given relevant biological constraints, sensation and learning shape neural “microstructures” in ways that are very similar across individuals. This implies that our cognitive states, including the meanings that we associate to linguistic expressions, are also quite similar (Segal, 2000).7 Therefore, when we talk about water, we may understand each other despite the fact that there is no “magical,” direct semantic connection that our thoughts and words entertain with H2O, no connection that guarantees that we are hooked to the same reality (McGilvray, 1998; Chomsky, 2000; Segal, 2000; Pietroski, 2003).

Internalism is the thesis that there are representations in the human brain that do the work of sense and reference, of intensions and extensions. If successful, the Twin Earth argument shows that these representations, in order to be “in the head,” must be unlike sense and reference, classically conceived. However, the relevant neural representations may still be related formally and systematically. For example, one can model the intension of an expression as an algorithm and its extension as the values computed by the algorithm (Moschovakis, 1994; van Lambalgen and Hamm, 2004a). This algorithmic view of meaning is appealing from a neuroscience perspective. In addition, the links between representations of language and representations of reality are internally constrained. Semantic facts (e.g., that there are natural kind terms, proper names, mass or count nouns in most languages) are grounded in facts about the mind (e.g., essentialism) and ultimately about the brain (Block, 1987; Carey, 2009). Internalism implies that these facts are necessary, although perhaps not sufficient, to “fix” extensions.

Three Systems of Semantics

What are the neural representations8 that “do the work” of sense and reference? To answer this question, consider what is involved in understanding

(1) The washing machine returned a pair of gray socks and three blue socks.

In particular, consider what is involved in understanding the quantified phrases ‘a pair of gray socks’ and ‘three blue socks.’ Here, the same word, ‘socks,’ with the same meaning, is used twice. Moreover, each phrase refers to a different set of socks—the two sets are disjoint—and each set contains a different number of socks. To explain the fact that we understand (1) and that even a three-year-old would understand it, one must postulate neural representations of types, tokens, and referents (Frege, 1892; Peirce, 1906).9 In (1), two tokens of the same type (‘socks’) are mapped, in the context of each quantified phrase, to two and three referents, respectively. The problem investigated in this book is how the human brain represents and computes with types, tokens, and referents. Two questions must then be addressed: (a) Where and how are lexical semantic types, tokens, and referents represented in the brain? (b) How are these representations linked during semantic processing and acquisition in children and adults? A complete theory of meaning in the brain is required to answer these questions.

The interplay between lexical semantic types, tokens, and referents grants us enormous flexibility and reach in expressing complex thoughts, such as

(2) The washing machine returned a pair of gray socks but no white socks.

(3) I usually store cotton socks in a drawer and wool socks in a cupboard.

(4) The washing machine transformed all my white socks into gray socks.

In all these sentences, as in (1), there are two tokens of the same type. However, the mapping between tokens and referents is very different in each case. In (2), the first phrase refers to a pair of gray socks, while the second refers to an empty set of white socks. In (3), information on the different spatial locations (drawer vs cupboard) of disjoint sets of referents is given. In (4), each phrase is mapped to the same set of referents, yet represented at different times—before and after the socks have undergone a process of transformation. A successful theory of meaning in the brain must answer questions (a)–(b) and explain how types may be activated, how tokens are generated, and how they are contextually linked to referents. Referent sets often vary in their numerosities and may, moreover, be spatially and temporally displaced. This book provides a theory of meaning in the brain that begins to address these issues explicitly, in ways that are coherent with formal semantic theory and experimental neuroscience. Importantly, here I aim to develop a theory of meaning in the brain, not a theory of concepts. The latter would explain how we can identify, distinguish, and classify socks versus tights, washing machines versus dishwashers, and drawers versus cupboards. Theories of conceptual knowledge in the brain have made great strides recently (Chen et al., 2017). There are some intersections between theories of meaning and theories of concepts, in particular with regard to semantic types. However, these remain different projects, because of differences in focus, methodology, and ramifications in different domains of cognitive science. Achieving a degree of integration is desirable but is beyond the scope of this book.10

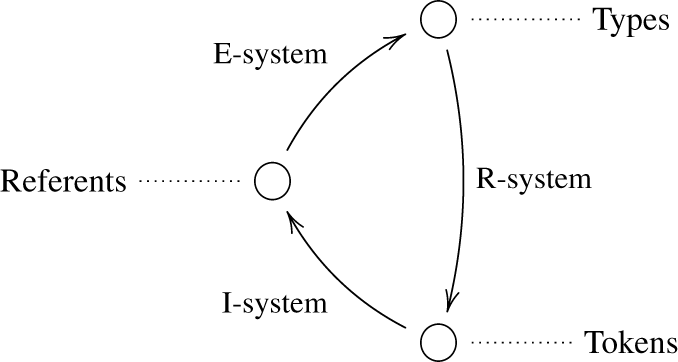

If one assumes that there are in the brain representations of types, tokens, and referents, then one should also assume that there are one or more brain systems that compute with these representations. The experimental studies reviewed in this book show that types, tokens, and referents are represented, respectively, in the left hemisphere’s temporal, inferior frontal, and inferior parietal cortices, in areas largely overlapping with the classical perisylvian language cortex. There is, in addition, evidence for the existence of three semantic systems in the brain that are part of this perisylvian network. These systems link representations of types, tokens, and referents, as illustrated in the diagram that follows.

The book includes three parts. Each part is dedicated to describing one of these systems from semantic, cognitive, and neural perspectives.

The first system is a system of relational semantics, or R-system for short. It is responsible for establishing semantic relations between words as they occur in sentences or discourse. During relational processing, lexical semantic types are linked to token representations and are bound together to form larger, more complex relational structures. The key nodes of the R-system’s network are the left inferior frontal gyrus and the left anterior and posterior temporal lobe. The R-system operates on short timescales, and relational processing is manifested in phasic components of brain signals, for example in the N400 in event-related potentials (ERPs). The relational structures computed by the R-system remain generally unavailable to introspection and conscious awareness. The theory of the R-system is presented in chapters 1–3.

The second is a system of interpretive semantics, or I-system. It is concerned with constructing a representation of discourse that is suited to the context and aligned to the meaning intended by the speaker or by the source of the message. During interpretive processing, tokens are mapped to referent representations. Interpretation may also involve elaborative processes (producing figurative and pragmatic meanings) and inference (e.g., deduction). In addition to the primary R-system network, the I-system engages the inferior parietal cortex and medial and lateral frontal areas. The I-system operates on longer timescales compared to the R-system, and interpretive processing is manifested in tonic components of brain signals, such as sustained negativities in ERPs. The representations of referents computed by the I-system are more readily accessible to introspection and conscious awareness and are used to initiate and guide thought and action. The theory of the I-system is presented in chapters 4–6.

The third is a system of evolutionary semantics, or E-system. It is implicated in tracking the degree of coordination between oneself and others, in particular so far as associations between words (or communicative signals) and meanings are concerned. During coordination, representations of referents, regardless of their perceptual availability, may be linked to new or existing representations of lexical semantic types, resulting in the extension or modification of the lexical semantic repertoire of the individual (learning) and possibly of the community (evolution). In addition to R-system and I-system regions, the E-system relies on right temporal areas and on the hippocampal system and is driven by striatal reward and motivation systems. The R- and I-systems are primarily processing systems, which connect types to tokens and tokens to referents during discourse comprehension. Instead, the E-system is primarily a (cultural) learning system, which is posited to explain how lexical types are acquired by infants, children, and adults and for how they might evolve during language use or in the course of transmission from one generation to the next. The theory of the E-system is presented in chapters 7–9.

These three systems are not anatomically separated “modules” but functional units operating in a concerted way during semantic processing and acquisition. These systems are neither disjoint nor arranged as in a chain. Instead, they are nested systems standing in an inclusion relation, like an onion’s layers:

R-system ⊂ I-system ⊂ E-system

This inclusion relation holds both anatomically and functionally. The R-system is a proper part of the I-system, which is, in turn, a proper part of the E-system. Therefore, the E-system coincides with the semantic system as a whole. There are several implications of this model. Anatomically, the E-system contains the I-system network and the I-system contains the R-system network. Moreover, some cortical regions, precisely those listed earlier, are specific to the E-system and are not engaged by interpretive processing, while other regions are specific to the I-system and are not engaged by relational processing. Functionally, the inclusion relation implies that, in general, the E-system operates based on input from the I-system, which, in turn, computes based on input from the R-system. The E-system generates the data structures (lexical semantic types) used by the R-system during relational processing, effectively closing the functional cycle. Another aspect of the functional inclusion relation is that the R-system samples words in the input at fairly high rates—but not as high as for perceptual systems and systems for morphology and syntax—processing at least all content words. The I-system samples words at a slower rate, interpreting (implicitly) referring expressions. Finally, the E-system samples relevant inputs at even slower rates, processing new words and whole communicative signals. These three systems of semantics are functionally separable by targeting system-specific processes by means of experimental manipulations of the stimuli or the task. Functional separability is coherent with a high degree of functional integration (Bergeron, 2016). Functionally separable systems, such as the R-, I-, and E-systems, may not be necessarily modular or (doubly) dissociable (Shallice, 1988; Carruthers, 2006; Shallice and Cooper, 2011; Sternberg, 2011; Bergeron, 2016).

Levels of Analysis, Theory, and Models

The main challenge for the theory presented in this book is to integrate analyses at multiple levels of description. Multilevel theory is averse to epistemological reductionism. The latter is the view that knowledge of semantic representations and processes, obtained from experimental and computational neuroscience, is more fundamental and may therefore be used to derive knowledge of meaning, as is generated in logic, linguistics, and philosophy. The multilevel framework for the analysis of information processing systems by Marr and Poggio (1976), made famous by Marr (1982), is both a cogent demonstration of the inadequacy of epistemological reductionism and a more realistic approach to intertheoretic relations in cognitive science (Hardcastle, 1996; Willems, 2011; Baggio et al., 2012a; Isaac et al., 2014; Baggio et al., 2015; Krakauer et al., 2016). According to Marr (1982), understanding an information processing system involves:

(a) computational analyses, identifying the information processing problems the system is set to solve or specifying the goal and logic of the computation;

(b) algorithmic analyses, providing representations of the system’s input and output and describing the constraints and algorithms for the transformation;

(c) implementational analyses, comprising structural and functional accounts of the relevant physical systems as they effectively carry out the computation.

Marr’s scheme accommodates most conventional modes of inquiry in cognitive science, ranging from analyses of the formal structure of language and thought to single-cell neurophysiology. This framework allows us to appreciate exactly why epistemological reductionism is bound to fail. As data analysis techniques improve, it becomes easier to extract information from brain data, including on the representational content of neural states (Mitchell et al., 2004; Haynes and Rees, 2006; Kriegeskorte et al., 2006; Poldrack, 2011). However, knowing that a pattern of distributed neuronal activity P instantiates a specific type of mental content C—for example, the logical meaning of conditionals as opposed to that of conjunctions and disjunctions (Baggio et al., 2016)—does not entail that one is able to provide a theory of C (classical propositional logic, with all its formal properties) entirely on the basis of a neural-level analysis of the class of events to which P belongs. Knowledge flows not from the bottom up, as a reductionist would assume, but from the computational level to the implementational level: one needs computational and algorithmic theories of mental representation and processing in order to identify and discriminate between neural representations and processes. Knowledge percolates downward through the levels of analysis in Marr’s scheme. This book follows this “law of epistemic gravity.” Each part opens with a chapter presenting computational and algorithmic analyses of the relevant processing problems: binding (R-system, in chapter 1), interpretation (I-system, in chapter 4), and coordination (E-system, in chapter 7).

Each level of analysis is populated by a variety of theoretical objects, ranging from compact expressions of principles (e.g., compositionality, incrementality, and related constraints on representations and processes) to phenomenological models (e.g., of the N400 component in ERPs) designed to explain and perhaps predict experimental phenomena, in the form of patterns of correlation between classes of stimuli and classes of neural responses. Multilevel semantic theories may be connected to formal theories of meaning through abstract principles at the computational and algorithmic levels and to basic processing facts through phenomenological models at the neural level. Theories should be evaluated for their (a) theoretical constraint (whether the structures posited by the theory can be modeled using tools from algebra, logic, and game theory) and (b) empirical adequacy (whether the cognitive and neural processes assumed by the theory’s phenomenological models provide adequate descriptions of observable aspects of behavioral and neural reality) (van Fraassen, 1980). Computational models, for example using neural networks, can contribute much to the theory’s success (Simon, 1992, 1996), so long as they remain anchored to both semantic theory and neural data, instead of “floating at both ends” (Post, 1971; Redhead, 1980), and so long as they avoid Bonini’s paradox, where the model is more complex or less transparent than the processes it purports to describe.

Aims and Scope of the Book

The aim of this book is to develop neural theories of meaning for the R-, I-, and E-systems. That is the area where the book tries to make original contributions. The computational and algorithmic analyses provided here, instead, owe much to current research in three fields of formal semantics. Specifically, I will apply vector-space semantics to a model of binding (R-system, chapter 1), discourse representation theory (DRT) to a model of interpretation (I-system, chapter 4), and signaling game theory to a model of coordination (E-system, chapter 7).11 The essential theoretical background is outlined using no more formalism than is strictly required to identify each system’s computational goals and logic and to specify the nature of the relevant input and output representations.

The implementational-level analyses developed in this book are presented in more detail and depth than both computational- and algorithmic-level analyses. The core elements of the neural theories of the R-, I-, and E-systems are, in all cases, phenomenological models with the following components:

(a) a set of brain regions and anatomical connections between these regions;

(b) a description of patterns of current flow within the specified network (a);

(c) a set of hypotheses on the functional significance of activation events (b) in each node or set of nodes in the specified network (a).

The goal is to describe how aspects of binding, interpretation, and coordination correspond to events in brain space and time, specifically to patterns of currents flowing across cortical regions through white matter connections, known based on experimental research. The proposed phenomenological models are partial (their consequences are limited to particular classes of observable phenomena) and purpose relative (their function is to constrain experimental designs so that hypotheses derived from the theory may be tested) (Achinstein, 1968; Da Costa and French, 1990; Morton, 1993). The explanations and predictions suggested by the proposed phenomenological models are:

(a) topological—specifying how semantic functions arise partly as a result of the structure of the relevant cortical networks, represented as directed graphs;

(b) dynamic—providing essential information on the temporal profiles of the relevant neural events, linked to the temporal characteristics of experimental dependent measures (e.g., ERP onset or peak latencies);

(c) mechanistic—holding that if currents flow from region A to region B, then activations in A cause B to become active, such causal links being mediated by direct, reciprocal anatomical connections between A and B.

Model-based explanations have a bounded contrastive form. Given the theory, a model may explain why a specific effect X instead of Y is observed, but it may not explain why X instead of Z is observed. Experimentation often reveals that the space of possible outcomes, in the chosen empirical domain, is constrained. Good models adhere to those constraints. Typically in neuroscience, the goal is to explain why the amplitude of a specific ERP component increases instead of decreasing or why in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) metabolic responses in a specific cortical region of interest increase rather than decrease. Moreover, good explanations are “hard to vary” (Deutsch, 2011): every aspect of the model contributes to the explanations it generates, so that modifying one or a few of its features reduces or destroys the model’s explanatory power.

The goal of this book is to present a theory of semantics in the brain based on computational- and algorithmic-level analyses and on partial, purpose-relative neurocognitive models of binding, interpretation, and coordination. The theory should account for major experimental findings by using topological, dynamic, and mechanistic explanations that are contrastive in form and hard to vary. The nature of the neural models of the R-, I-, and E-systems presented in chapters 3, 6, and 9 delimits the scope of the present work. Although drawing amply from several areas within linguistics and psychology and moderately from logic and philosophy, this book fits comfortably within modern imaging-aided cognitive neuroscience. The theory of meaning in the brain presented here aims to strike a balance between achieving a high level of theoretical sophistication, required in order to steer the hypothesis space in new directions, and generating explicit hypotheses, testable using the tools and measures available to most researchers in psycholinguistics and cognitive neuroscience today.

Notes

1 For our purposes, fact A grounds fact B if and only if B holds by virtue of A. For an introduction to grounding, see Berto and Plebani (2015). For a discussion of grounding as noncausal explanation, see Fine (2012) and Audi (2012). For an application to the mind-body problem, see Ney (2016).

2 Semantics is epistemologically more fundamental, not only in contexts of discovery but also (and most important) in contexts of justification (Reichenbach, 1938); that is, the theory of meaning in the brain proposed in this book is based logically on formal theories of semantics and pragmatics.

3 These notions are variously defined within particular theoretical frameworks in formal semantics (Gamut, 1991). I will ignore this further complication here. See chapter 4 for a discussion.

4 There is copious literature on the Twin Earth argument. One of the most compelling confutations is provided by Crane (1991). He suggests that H2O and XYZ are different types of water. Speakers on Earth and Twin Earth would thus share a concept that includes both molecules in its denotation. Differences in the chemical compositions of different water types may not entail differences in the meaning of ‘water.’ See Chomsky (1995a) for a related argument.

5 In line with the ontological thesis that facts about meaning are grounded in facts about the brain.

6 Causal theories of language and meaning have been proposed by Stampe (1977), Dretske (1981), Papineau (1984), Fodor (1984, 1987), Lloyd (1987), Millikan (1989), Devitt (1996), Usher (2001), and Ryder (2004). This tradition dates back at least to William of Ockham (Normore, 1991).

7 This is not unproblematic, but it is in accord with materialistic or physicalistic views of the mind. One may assume that mental states are not simply grounded in brain states but supervene on them: there may be no change in mental states without a change in brain states (Davidson, 1970).

8 A neural representation is such that (a) it can be described in a formal language and interpreted in terms of mathematical structures (e.g., algorithms or sets), (b) it participates in computations with other representations, (c) it is physically realized as a pattern of neural activity, and (d) it performs specific functions for the organism, as defined by cognitive or behavioral goals.

9 Peirce (1906) is credited with introducing the distinction between types and tokens. The standard reading of Frege (1892) suggests that sense is a property of types. If senses determine denotations, then reference is context-invariant; for example, ‘socks’ denotes the set of all socks (Gamut, 1991). This concept of reference is central to the project and the spirit of (early) analytic philosophy, but it is not suited to a theory of meaning in the brain (chapter 4). In order to construct a context-sensitive notion of reference, one must rather assume that the “determination relation,” which holds between sense and reference, is either applicable to or mediated by tokens (Sainsbury, 2002).

10 An excellent theoretical springboard is provided by chapters 9–12 of Jackendoff (2002). Among others, Lakoff (1990) and Gärdenfors (2000) are two classical and influential integrative works.

11 For an introduction to semantics and pragmatics, see Gamut (1991). References on vector-space semantics, discourse representation theory, and signaling games are given in the relevant chapters.