CHAPTER THREE

Amulets

em sa-k usei-tu ma neteru

Thy protector, being powerful with the gods.

The use of amulets has existed since the beginning of humanity, and continues. Amulets represent beliefs and superstitions so old that even the Egyptians were, at times, doubtful about their origin and meaning.1

Amulets are perhaps the most renowned artifacts of ancient Egypt. They were used in Egypt long before literacy prevailed. The word amulet is taken from an Arabic root which means “to bear, to carry.” It defines a broad class of objects and adornments that were made of various materials employed to protect or otherwise serve the individual. They were used by both the living and the dead to protect from visible and invisible enemies. Charged with words of power, amulets radiated supernatural powers that all classes of Egypt considered necessary to life.

Amulet Types

There are two types of Egyptian amulets: those inscribed with magical script and those that were not inscribed. Prayers or magical words were recited over amulets worn by the living and also placed on the dead at funeral ceremonies. The common man did not have the power to employ them. Only magicians and priests held the power to charge amulets for use. The process included carving the words of power upon the objects, which then were believed to have a threefold power: the power inherent in the substance of which the amulet was made, the power of the words recited over them, and the power that lay in the words inscribed.

Amulets were crafted of gods in human or creature form. These were placed on jewelry, headrests, temples, and every conceivable furnishing or object. Bangle bracelets often served as amulets. Selections of hieroglyphic signs and pictorials decorated the bangles, which were commonly made in silver and gold. Hieroglyphic signs like the wedjat, ankh, and djed pillars were used. Snakes, baboons, falcons, turtles, and the horned mask of the goddess Bat are also among the many pictures used.

Old seals from jars, boxes, and documents were considered powerful amulets. Those inscribed with royal titles or the Pharaoh's throne names were sought after for their immense power and value. Certain seals were strung on cords and worn like beads.

Amulet Uses

In the magical papyri, we learn that the magicians placed great importance on how amulets were worn. There were three primary ways of wearing amulets: as pendants worn around the neck, as bracelets, and as amulet bags.

Pendants were worn for the protection or empowerment the wearer derived from them. They were also used to express the devotion a person had to a particular deity. These pendants allowed the wearer to use the divine image and power of a god or goddess to accomplish goals in daily life, and in magic. They depicted animals, plants, deities, tools, furniture, ritual objects, and parts of the human body. They were made out of stone and many other natural materials. Typically, pendants were carved, engraved, or drawn upon to capture a form that would give power. A good example of this is the scarab, which was a popular amulet of Egypt made of the genuine scarab beetle, or of an imitation carved from many types of stones.

Written magic, or small magical objects, were later placed within cylindrical pendants made of gold, silver, and other materials. These could be opened and closed. Amulet bags also held magical script written on papyrus or linen. These bags were tied around the neck or worn elsewhere on the body. Children wore amulet bags that contained divine decrees issued in the name of the god or goddess who gave an oracle as to the child's fate in life. The oracle was written on papyrus or linen and then rolled up and placed in the amulet case or bag to be worn. The decrees commonly were positive, assuring that the child would live a long, healthy, and prosperous life. Some decrees vowed to protect against sorcerers, the Evil Eye, and numerous hazards. Others promised to help the owner of the amulet cheat fate.

Amulet bags were popular. Sa is an Egyptian word that can mean a group of objects, the cord they were strung on, the bag that contained them, or the words and gestures needed to “activate” them.2 A looped cord is the hieroglyph used to write this word. The cord itself was made of leather or linen thread, and served as an amulet in its own right. Many were tied with several knots by the magician in the course of a rite.

Amulets were worn by children to fight off disease and injuries like the sting of a scorpion. Women wore them to protect against risks in childbirth. A pregnant woman often wore one or two amulet bags containing an assortment of ingredients to protect her during childbirth. The contents might have included parts of the lip and ear of a donkey, a dried chameleon, the head of a hoopoe, seven silk threads (representing the Seven Het-herus), or a written magical spell. If a woman battled infertility, an amulet made from any object that resembled the male or female genitals, or a pregnant woman, was a powerful aid. Women and children also wore amuletic bracelets, earrings, and anklets.

Quarrying expeditions, hunting, traveling by sea, and warfare were common hazards for men. Amulets, as well as magical spells, served as practical protection for these activities. Amuletic belt clasps were worn below the navel by men. As Egyptians believed a persons emotions and power resided in the stomach, these clasps were probably used to protect or empower that region. Men also wore amuletic bracelets. In 1700 B.C., rings became popular.

Dreams fell under the protection of amulets. Headrests were constructed of limestone and engraved with the god Bes grasping and biting snakes that represented the dangers of the night, among which were dreams. Each period of sleep was believed to be a brief excursion into the underworld, where spirits and demons could cause nightmares. While dreams were thought useful in divination, they also threatened intrusion by unsavory, unworldly beings into the life of the sleeper. This may provide another clue as to why permanent amulets existed that could be used around the clock.

Some amulets were worn permanently, usually in the form of jewelry. Others were used in temporary situations that required the immediate influence of a charged aid, such as illness, injury, or childbirth. These magical objects were made and used in countless ways. Surviving amulets exhumed and studied by Egyptologists have given us a great deal of knowledge about them. In chapters 5 and 6, you will learn how to use amulets in divination and magic.

Amulet Deities

In magical papyri of the second millennium B.C., the goddesses Auset and Nebt-het are associated with spinning and weaving linen cords to make amulets, especially amulets of health. Another deity named Hedjhotep, is similarly depicted. The goddess Neith accepts the woven cords from these gods and goddesses, and ties knots in them for magic. Pictures of the deities associated with making amulets were often drawn on linen and served as temporary amulets.

Materials Used to Make Amulets

Because amulets were traded, exported, and copied throughout the ancient world, countless examples have survived. The earliest Egyptian amulets were made of green schist, which was cut into various shapes of animals and creatures. Numerous samples were found in the prehistoric graves of Egypt. Archaeologists found amulets that had served as spiritual and magical offerings in houses, temples, and shrines.

In later times, cornelian, green basalt, gold, granite, marble, blue paste, blue and red glass, glazed porcelain, red jasper, obsidian, hematite, lapis lazuli, bronze, wood, and numerous other substances were used in the manufacture of amulets. The Egyptians used such a variety of natural stones in their design that you can probably make an amulet today of just about any type of stone and remain within tradition.

Natural or man-made objects can serve as the raw materials for amulets. The material, shape, scarcity, texture, or color of a natural substance can be the source of its power. Strange and rare materials were thought to hold the most power. Seashells and river pebbles were commonly used. Plants and long-lasting herbs were used, although few such amulets have survived. Cowrieshells shaped like an eye or the female genitals were used as amulets popular for warding off the Evil Eye. Girdles were made from cowries to protect a woman's fertility. Imitation cowries were made in gold, silver, and faience.

Other natural amulets include animal parts like claws, cat hair, a snake's fang, a camel's tooth, and various other portions of animal bodies. Many, such as the head of a hoopoe, are impractical and undesirable today.

How Egyptians Charged Amulets

Any object that can be worn or carried, and is charged in a ceremonial rite with energy through inscription or spoken magical script can serve as an amulet. The power of an amulet is made possible by the magician infusing it with energy and inscribing upon it or reciting to it some purpose that will serve its owner. The charged amulet will amplify that energy and promote its purpose.

In Egypt, magicians were summoned by royalty and laymen who required the special quality of an amulet to overcome a situation, gain protection, or to be empowered in some fashion. Commoners also made and used their own amulets. If an individual had an object to infuse with the needed power and had some way of charging it, it became a functioning amulet.

How to Make an Amulet Using Modeling Compound: Modeling compound is perhaps the best choice for making amulet pendants, since it is easy to use. You will need a pencil, one sheet of paper, modeling compound (which you can purchase at a craft shop), a piece of craft wire approximately two inches long, two sheets of waxed paper, a small knife, a standard oven, some acrylic paints, and a small paint brush.

- Choose the shape for your amulet and draw it onto a piece of paper. This will serve as a pattern.

- Roll out and flatten a three-inch ball of the compound between two pieces of waxed paper.

- With a small knife, cut out the shape and details of your amulet in the compound, using your pattern.

- Place a loop of craft wire through the top.

- Bake the amulet in your oven following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Once baked, use the acrylic paints to decorate your amulet.

Place your completed amulet on a leather throng or gold chain to wear it. Wood is also ideal for making amulets. You can carve a picture of the amulet shape onto a wood surface, or carve the amuletic object from the wood. Stone and metals require a specialized skill in cutting and design. Amulets were also written on linen, papyrus, thin sheets of metal, and the leaves of certain plants. You can choose to employ written and drawn amulets instead of carving or engraving figures. Write down the magical script or drawing of your choice, roll it up, and wear it around your neck as an amulet.

You can wear your written magic by inserting it into a pill box and some small vessel pendants. Vessel pendants are used to hold essential oils, perfume, and a variety of substances. These can be purchased at most jewelry stores. These modern vessels are very similar to the Egyptian cylindrical pendants.

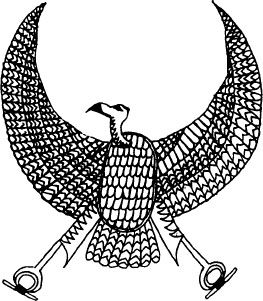

How to Charge an Amulet: You are provided with a list of Egyptian amulets in the next section. These can be used for several purposes. First, you need to know how to charge an amulet to capture its power. The example below is typical of how an ancient magician charged an amulet. You may follow these instructions for any amulet listed below. I will use the amulet of the vulture in the following example. The amulet of the vulture was intended to bring the power of Auset, known as “the Divine Mother.” Traditionally, it was made of gold in the form of a hovering vulture, with the sign of infinity, the shen, held in each talon. (See figure 9.)

Figure 9. Vulture amulet.

- You can choose to simply draw the vulture onto a piece of papyrus or white paper. You can also take a small piece of wood or stone that can be worn around the neck and carve this amulet upon its surface. Any material, natural or man-made, is suitable for use.

- Once you have made your amulet, you need to charge it with words of power before wearing it. You may conduct this ritual in as ceremonial a way as desired.

- Choose a private location or room in your home where you can conduct the charging without interruption.

- You may wish to decorate an altar for charging the amulet. Lit incense, consecrated water, anointing oil, and other items help to shift your consciousness and enhance the environment for your ritual. Lay the vulture amulet in the center of your altar, surrounded by the above purifying items.

- The following magical script is taken from chapter 157 of The Book of the Dead, but we know that the living also used this amulet. (I was unable to find appropriate magical script to charge it for this purpose.)

The script begins by describing the care Auset provided Heru when she raised him in the papyrus swamps. Next, it tells of Heru's acceptance into the company of gods. It ends with a description of Heru's war with Set, whom he conquered through the power and protection of his mother, Auset. By reciting this script over your amulet, you charge it with the power of Auset and of Heru. You will be made victorious. Battles can be won. You are protected under Auset, the mighty goddess of magic.

Auset cometh and hovereth over the city, and she goeth about seeking the secret habitations of Heru as he emergeth from his papyrus swamps, and she raiseth up his shoulder which is in evil case. He is made one of the company in the divine boat, and the sovereignty of the whole world is decreed for him. He hath warred mightily, and he maketh his deeds to be remembered; he hath made the fear of him to exist and awe of him to have its being. His mother, the mighty lady, protecteth him, and she hath transferred her power unto him.

When the charge is complete, you may wish to anoint your amulet with a dab of water or oil to consecrate it and “seal” the charge.

Using Your Amulets

Amulets can serve a variety of your needs. They can protect you from fierce entities conjured through evocation or negative energies released during magical ceremonies. Traveling a long distance from home, taking an unnerving test, fighting an illness, or decreasing the effects of an enemy's work against you are only a few of the situations in which an amulet can provide protection, or empowerment. Amulets can serve you well at any time in your life that you feel vulnerable or feel the need to have your power protected or charged.

Egyptian Amulets

This section provides the most popular amulets used in divination and magic by the living. It lists the amulet name, illustration, definition, and how the amulet can be used.

Ankh

The ankh is perhaps the most popular amulet to survive to our modern day. They are found in most jewelry stores and are worn traditionally around the neck, just as they were in Egypt. Typically, they are made of gold, sterling silver, copper, and many other metals.

The ankh is a symbol of life that is thousands of years old. As an amulet, it is used to lengthen and protect life. In Egypt's earliest history, the ankh existed as a popular amulet that every god carried. As a hieroglyphic sign, ankh is the word for life. Its exact origin, or what the ankh represents in form, is hotly debated. Some Egyptologists claim that it represents a penis sheath, while others state that it is the form of a sandal strap, since in ancient Egypt, this strap had a name which resembled the word for life.

Because the ankh is also a hieroglyphic sign, its power can be captured simply by writing it. This can be done during any magical work, or it can be drawn on papyrus, rolled up, and worn on a cord. The ankh is often seen on ancient jewelry with the wedjat and the djed pillar. Combined, these three symbols provide potent protection.

Animals are also found on artifacts with the ankh, among them snakes, baboons, turtles, and falcons. It is logical to choose fierce and intelligent animals to place beside the ankh. These, and the two additional symbols above, were often fashioned into gold and silver necklaces to be worn by a child.

It is interesting to note the apparent relationship between the Egyptian word akh, which describes the part of a deceased person that acquired magical powers in the afterlife,3 and that of the ankh as a word and amulet.

Buckle (Tyet)

The buckle or tyet is symbolic of the girdle of Auset. It is typically made of gold, gold-plated metals, wood, black stone, red glass, red jasper, cornelian, and other red substances. The color red is symbolic of the blood of Auset. The tyet was worn as a pendant.

This amulet comes from a story in Egyptian mythology. When Set killed his brother, Ausar, he did not know that Ausars consort, Auset was pregnant and carrying Ausar's heir, Heru. Terrified that Set would find out she was pregnant and kill her, Auset fled to Chemmis in the Delta, where she gave birth to Heru. To protect the newborn Heru, she took off her girdle and tied it around him. It is the knot of this magic girdle that was used to form the amulet tyet, which became a symbol of protection to the Egyptians.4 The tyet also gives power to access every place in the underworld and allows the wearer to point “one hand toward heaven, and one hand toward earth.” This makes it a powerful ally in evocation, out of body projection, or any magical work.

You can make the tyet amulet out of any material. Red-colored stone or other material is best. To charge the amulet and obtain the power of Auset's blood, recite the following secret script over it:

The blood oí Auset, and the strength oí Auset, and the words of power oí Auset shall be mighty to act as powers to protect this great and divine being, and to guard him (or her) from him that would do unto him anything that he holdeth in abomination.

String the amulet on a pith cord and wear it around your neck for protection and empowerment.

Frog

The frog is a symbol of the birth goddess, Heqet, who appears as a human woman with a frog's head and typical Egyptian wig. Heqet is a primordial creator-goddess. Because Heqet helped Ausar rise from the dead after Set murdered him, the frog is also a symbol of resurrection.

Frogs appeared on gold rings around 1400 B.C. These rings sometimes had a frog depicted on one side of the bezel and a scorpion, representing the protective goddess Serqet, on the other. It is thought that these rings were worn as protective amulets in life and by women in childbirth.

Frogs also appeared on glazed steatite magic rods around 1800-1700 B.C. For a magician to place this symbol upon such a vital ritual tool signifies that it had great importance, probably as a puissant amulet of creation. Small amulet pendants of frogs have been found in burial chambers. These amulets, made from alabaster, carnelian, and other natural materials, were part of funeral ceremonies promising resurrection.

You can make a frog amulet out of wood or inscribe its form onto a stone for a necklace. If drawn onto candles, papyrus, paper, and magical tools, the shape serves to amplify your magical creations. For a woman, this amulet has a particular meaning. The women of Egypt swore by its ability to protect during the phases of a woman's cycles, life, and childbirth. It was thus worn with special pride by women, symbolizing their role in the creation of life and existence.

Lion

The fierce disposition and strength of the lion made it popular for protective amulets. The Egyptians believed that two lions guarded the eastern and western horizons. The Lion of the Eastern Horizon observed the rising Sun each morning, and the Lion of the Western Horizon guarded the Sun by night. Lions lived in the deserts, and the Egyptians reasoned that the Sun died there each evening, then was born again there in the morning.

Egyptians required a guardian at night so that a new day of living could be experienced each morning. Beds and headrests were decorated with lion motifs. A lion made of faience was threaded onto red linen and secured to a man's hand as a protective amulet during sleep, to guard against all visible and invisible life-forms that could cause nightmares, health problems, and threaten harm.

Images of lions decorated jewelry and magical tools. Lion amulets were used symbolically in magic to defend against chaotic entities, negative energies, and hostile deities. Enemies were easily trampled under foot as the lion, along with other dangerous animals, worked to defend the magician.

Lotus Flower

To the Egyptians, the white and blue lotuses were the perfect flowers. The blue lotus was sacred because its delightful perfume was the divine essence and sweat of the Sun god, Ra. The lotus adorned columns inside temples and on the porticos which led to courtyards at the villas of the wealthy. It was revered as a symbol of regeneration: The lotus rises from the water each dawn to open its petals to the Sun god, Ra.5

Goddesses and priestesses are portrayed carrying the lotus/lily wand in statues, in paintings upon tomb walls, and in papyri which depict religious and magical ceremonies. Women carried real lotus flowers for pleasure and in religious rituals. This symbol of regeneration can be used in magical spells prompting a new beginning, upon love charms, in spiritual ceremony, and for any situation requiring reformation.

Menat

The might of the male and female organs of generation are supposed to be mystically united within the menat,6 which represents the power of the primordial reproduction that began all life. This amulet was used in Egypt as early as the 6th Dynasty. Gods, kings, priests, and priestesses wore or carried the menat. It can be worn around the neck or carried in the hand. It is believed to possess magical properties and to bring health, joy, and strength to its owner.

The menat was held in the left hand by priestesses at religious festivals and offered to the gods at shrines within homes and temples. In the home, it was also presented to guests by their hosts as a sign of hospitality. The menat was the ideal gift to wish good tidings to another person.

The goddess Het-heru is associated with the menat. She represents love, beauty, and happiness, and was sometimes invoked by the Egyptians to nurse the sick and depressed. The root word for nurse is related to the word menai, which further enforces its use as a word of power to soothe emotions and bring well-being to its owner.

Menat pendants and hand-held devices found in Egypt often have inscriptions to Het-heru upon the disk. One such inscription reads, “Beloved of Het-heru, lady of sycamore trees.” Such written magic was used to charge the amulet, and to harness Het-heru's power and derive the sacredness of the sycamore tree.

The menat is a curious object. It consists of a disk with an attached handle and a cord. Pendants were made of faience and hard stone. The hand-held version often had a handle and disk made of bronze. The disk was hollow and bore inscriptions like the head of a cow, which is the sacred animal to Het-heru.

Chapter 2 gives further information on how to make a hand-held menat to use in your practice.

Nefer

The nefer was a musical instrument that was played in Egypt. For the Pharaohs amusement, musicians, dancers, and acrobats often performed before royalty within the great hall. Beautifully adorned ladies wearing cones of scented fat atop their heads strummed the nefer, as dancers glided to its sound. This instrument may also have been used in temple ceremonies. Similar to our modern guitar, its strings were plucked with the fingers.

The amulet represents the cheerful sound of the actual instrument, which brought feelings of good fortune and happiness. It was made small enough to wear as a pendant, and carved from red stone, carnelian, red porcelain, and other substances. It was a favorite pendant, often worn attached to necklaces and strings of beads.

You can make a nefer by carving its shape into stone or wood. You can also draw it on papyrus or paper, or carve it from candle wax. Use it in magic for good fortune, to obtain favor, and to ensure success.

Papyrus Scepter

This amulet represented the scepter used by priests, priestesses, royalty, and the gods in both religious and magical ceremonies. The scepter is also symbolic of power and authority.

In early Egypt, the amulet apparently was used only in funeral ceremonies. In the 24th Dynasty and beyond, it seems that it represented the power of Auset, who derived her own power from her father, the husband of Renenutet, the goddess of abundant harvests and food.7 Traditionally, it was made from light-green or blue porcelain, or mother-of-emerald, and was worn on a cord.

You may design your own scepter out of any material to wear or carry with you. You can draw the scepter onto papyrus, roll it up, and place it inside a vessel-pendant to wear around your neck.

The papyrus scepter is best used in magic for vigor, renewal, and to harvest needed things. Healing magic, success, and good fortune are possible uses, and it may be used to harvest the love of another in love spells.

Scarab

The scarab is the best known of Egyptian amulets. The scarab beetle is a dung beetle that rolls a ball of dung with its hind legs, lays its eggs in it, and then buries it in a dug hole. The scarab beetle still exists today.

The scarab appealed to the Egyptians for its crafty wisdom in rolling dung and using it to lay its eggs in—both acts of creation. These beetles roll the balls from east to west, bury them for eight to twenty days, then fetch the balls and throw them in water so that the scarabaei can emerge. This process seemed to mimic the Sun as it was propelled across the sky. The Sun contained the germs of all life, and the insect's ball contained the germs of the young scarabs. Both were creatures who produced life in a special way.

The scarab-beetle amulet is an image of the god of becoming, Khepri, who is the regenerated Sun at dawn. It is symbolic of the continuous process of creation. The actual beetle was also used in magic, however. Magicians drowned the beetles in the milk of a black cow, then placed them on a brazier so that the gods summoned for divination would come quickly and answer inquiries truthfully. In early Egypt, if a magician wished to defeat some sorcery worked against him, he cut off the head and wings of a large scarab beetle, boiled them, steeped them in the oil of a serpent, and then drank the mixture.

Egyptians made scarab amulets by the thousands, and in numerous varieties. The amulet's common appeal did not diminish its power, however. It remained a potent amulet into the fourth century A.D. Amuletic bracelets were made of knotted leather cords, scarabs, snakes, and other amulet devices. These were used in divination to protect the magician, or his medium, from hostile gods and forces. In magic, it worked in much the same way.

In order for the amulet to work for gaining favor and success, or for use in love spells, it had to be made of heliotrope engraved with a scarab encircled by a snake known as Ouroboros—a snake swallowing its tail. This snake is symbolic of totality. The magical names of the scarab and snake should be written in hieroglyphs on the reverse side of the stone.

Scarab amulets were made of every kind of natural stone and metal. Green glazed scarab pendants were worn on a gold chain. Sometimes scarab amulets were made with a band of gold across and down the back where the wings joined together.

This amulet can be made from any substance. You can also buy scarab jewelry from sources found in the Egyptian Resources section. Words of power that charge it for magic are usually stamped or engraved around the scarab form.

How to Make a Scarab Ring: The spell below is similar to one found in A Fragment of a Graeco-Egyptian Work upon Magic (Publications of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 1852).8 You can use this spell to charge any scarab amulet. To make a ring, you will need an oval of emerald or other green stone, a Dremel power tool and bits for stone engraving or other stone carving tools, thick gold wire that you can shape to the diameter of your finger.

- Engrave the picture of a scarab onto the emerald stone. You can cut the form of the scarab into the stone, but it is difficult.

- On the reverse side of the beetle, carve the figure of Auset.

- Bore a channel through the stone and pass a gold wire through it.

You can conduct the following charge on the 7th, 9th, 10th, 12th, 14th, 16th, 21st, 24th, and 25th days of any month. To do so, you will need a scarab amulet, a table or altar, a small container or vessel, a square of linen cloth, a piece of olive wood (optional), a censer, myrrh and kyphi resin incense, chrysolite (see glossary), and an ointment of lilies, or myrrh, or cinnamon.

- Place the amulet on a table. Lay a pure linen cloth and some olive wood under the table.

- Set a small censer burning myrrh and kyphi in the center of the table as an offering.

- Have a small vessel containing chrysolite in which you put ointment of lilies, or myrrh, or cinnamon.

- Bless the scarab ring, then lay it in the vessel of ointment.

- Offer it in the incense smoke from the censer.

- Leave the ring in the ointment vessel for three days.

- After three days, place some pure loaves, fruits of the season, vine sticks, and other offerings on the table.

- Remove the scarab ring from the ointment and anoint yourself with it.

Anoint yourself early in the morning, facing east, and recite the following script:

I am Tehuti, the inventor and founder of medicines and letters; come to me, thou that art under the earth, rise up to me, thou great spirit.

At dawn, it was believed that the Sun was under the Earth, and slowly emerging. In this magical script, you are summoning the powers of the god Khepri, the Sun, and charging your amulet permanently to use as you desire.

Scorpion

The scorpion symbolized chaos and was thought to have been the form taken by the restless dead. Scorpions posed an everyday threat as well. Its sting, aside from representing malicious ghosts, or amplifying the effects of the war between order and chaos, could prove deadly. Thus magicians used scorpion amulets to protect from the danger of hostile entities or the forces of chaos.

Scorpion amulets may have represented the goddess Serqet, who was depicted as a woman with a scorpion on her head. Serqet was considered a friendly goddess who helped at the birth of pharaohs and gods. She is also one of four goddesses who guarded embalmed bodies in funeral ceremonies. Serqet means “she who causes to breathe”—a name given to induce flattery so that her powers could be used against actual scorpion stings. The idea was to conquer the living scorpions with the identical power of their goddess. Serqet was used to heal, but she could also inflict harm on enemies.

Scorpion amulets were frequently used in medical magic and were placed around the neck of patients who had been stung, while words of power were spoken. They repelled peril and gave protection. A scorpion was often incised on the base of rings that had frog bezels. These rings were worn by children to protect them against scorpion stings. Another amulet used in a similar fashion was that of a serpents head.

The Egyptians desired order and the well-being of all. Spells invoking the protection of the scorpion were placed on temple gateways, on plaques in houses, and on amulets. Scorpion pendants were made of many substances. Blue glass was a popular choice in the third through first centuries B.C., and some had traces of gilding.

You can make your amulet from wood, draw it upon papyrus, or cut its shape in a variety of stones.

The Number Seven

Seven was a number of great significance in . Egyptian magic.9 The goddesses Sekhmet and Het-heru both had seven forms. The actual number seven was not used on amulets, talismans, or for magic. Rather, the number's power was invoked by grouping deities, figures, statues, pictures, magical names, or just about anything in series or arrangements of seven.

The sevenfold Het-heru is a gentle, lovely sky goddess who delivered happiness and protected women and children. Her aspect of the Seven Het-herus partakes of the nature of good fairies.10 Invoking the Seven Het-herus in divination and magic promised powerful assistance. They decreed fate, both good and bad. They were frequently invoked in love spells, one of which you will learn in chapter 6. They also declared the fate of newborn children.

Because magicians wished to avoid, or control, the effects of fate, ancient papyri tell us that they often had to work against the Seven Het-herus in order to acquire a desired outcome. If flattery and offerings did not succeed in convincing the Seven Het-herus, magicians employed negotiation, threats, or shape-shifted to a dominant god-form to achieve ultimate control of fate.

Sekhmet was created as the opposite form of Het-heru. She is the goddess of the burning Sun, war, destroyer of enemies, personification of the awesome power of the solar eye energy (see Eye of Ra, below). She was often invoked in magical rituals to protect the state of Egypt. Ancient papyri state that the priests of Sekhmet seemed to specialize in medicine, and so her power could apparently be channeled for healing.

The Seven Arrows of Sekhmet guarantee misfortune, illness, or other negative effects. They were powerful weapons that could be harnessed by magicians for use in spells. One ancient spell uses them against the Evil Eye. Sekhmet also had seven negative messengers that could be sent to cause nightmares, illness, and numerous hazards to enemies.

Divination scripts included the invocation of seven kings, the Seven Het-herus, seven forms of Heru, and a score of entities in groups of seven. There are divine manifestations of messengers in groups of seven that were emanations of any deity, which were summoned for use in divination and magic.

In many divination scripts, scribes instructed that the script be recited seven times. The number seven retained importance in spoken magic. References to “seven heavens” and “seven sanctuaries” can also be found in numerous papyri.

You can use a sevenfold form of any deity in your practice. It seems that usually these were invoked or summoned through written magic. Making wax figures or statues in groups of seven for magical purposes invokes the number's power. Grouping the celestial heavens, and any spiritual or magical place or thing, by seven ensures great achievement.

Serpents

Serpents in many forms graced Egyptian amulets. Many were for practical protection against snake bites, but some depicted enemies or were used as potent magical devices. One particular snake, the Ouroboros, was depicted in a circle swallowing his tail. He was symbolic of totality, and appeared on amulets of protection or any amulet requiring totality.

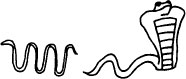

Many deities were pictured with, or represented by, a serpent form. The snake illustration on the left symbolizes destiny and represents the god of destiny, Shai. Depending upon how many loops the snake has, it has a different meaning. Trying to decipher the different snake portrayals has been a challenge for Egyptologists.

The cobra, shown above on the right, was given royal status and goddesses reflected the cobra's might. There were two royal cobras, both depicted as female. One, a goddess of predynastic times named Edjo, symbolized sovereignty over Lower Egypt and was drawn as a human woman. The second goddess, named Nekhbet, ruled Upper Egypt and was drawn as a vulture or a cobra. The cobra was a popular deity form whose chief duties were protection, granting dominion, and spitting fire against enemies.

The amulet of the cobra was called a uraeus and was worn on the brow, attached to fillets or to the crowns of all royalty and gods. The cobra was placed on funerary masks, skullcaps of royal mummies, and added to other amulets, such as the Eye of Heru. Numerous uraei lined the columns and upper walls of temples and other buildings.

A wooden figurine of 1700 B.C. found in a tomb under the Ramesseum at Thebes is a lioness goddess (or a priestess in her form) holding metal serpents that were employed in magical rites. This proves that serpent forms were used in magic, but it is not known how they were used.

Serpents were also used to threaten enemies in Egyptian mythology. Auset sent a serpent to bite Ra in order to learn his secret name. Ra was challenged by a monster serpent god named Apep. Serpents were consorts of the hostile god, Set. Some magical papyri have pictures of a pantheistic deity trampling serpents and other dangerous creatures under foot.

Serpents were made out of various metals and stones. Red stone, red jasper, and cornelian were popular materials. You can make serpent amulets to wear or carry, or use them in pictures and figures for magic. Their use is varied. Like many symbolic creatures, they are considered as either good or bad and can be used in any type of magic.

Solar Eye

The solar eye is the powerful eye of the Sun god, Ra, and is personified as a goddess who defeated the enemies of order and light.” The Eye of Ra has many goddesses who embody its power. The three most important used in magic are Het-heru, Sekhmet, and Weret-Hekau. It is one of two great amulets used in magic. The other is the Eye of Heru—the Moon eye. In Egyptian mythology, the two are often considered identical in meaning and power. It is frequently difficult to identify which eye is being depicted in Egyptian pictures, because the two were often drawn alike. The solar eye is the right eye, and the moon eye is the left eye. Often, both were shown together to form an amulet issuing the healing power of Heru and the protective power of a mighty eye goddess, such as Sekhmet.

This amulet derived from the creation story of Egyptian mythology. In the beginning of existence, there was darkness. The god Ra-Atum had two children, the air god Shu and the moisture goddess Tefnut, who ventured out into the darkness to explore. Fearing he had lost them, Ra-Atum removed his divine eye from his forehead and hurled it into the darkness to find them. His eye became the Sun, and was known as the solar eye that lit up the darkness.

This eye was often drawn on the front of magical papyri to protect magical words and charge them with great power. It was used in love spells to cause a couple to separate so the magician could procure his desire. In a Graeco-Egyptian magical papyrus, a spell survives in which the magician invokes a goddess embodying the power of the solar eye to infuse with power a scented oil he will use as an aphrodisiac.

Traditionally, the solar eye was made out of green and black faience, granite, porcelain, silver, and many other materials. You can make the eye out of stone, wood, or papyrus to wear as an amulet. Drawing it upon magical papyrus, alone or with other amuletic pictures, is both traditional and effective. Use the solar eye in love spells, to charge magical tools or scripts, for protection, and in defensive magic.

Djed Pillar

The djed pillar became the most important religious symbol in Egypt. The ceremony of constructing the djed pillar at Djedu (later known by the Greeks as Busiris) symbolized the reconstituting of Ausar's body, which was a most dignified ritual in connection with the worship of Ausar. This ceremony reflected the mythological story of Heru carrying out funeral rites for his father, Ausar, by raising the sacred pillar to assist his father's resurrection to become king of the underworld. The ritual raising of the djed pillar became traditional at certain festivals.

The pillar receives its name from the town of Djedu in Egypt where the oldest-known cult of Ausar existed. Its significance is not entirely known. It may have represented a sheaf of corn in agricultural rites, as Ausar had an aspect as a corn god. Later, the pillar was a sacred relic representing Ausar's backbone, symbolizing endurance, strength, and stability. Some Egyptologists think this amulet represents the tree trunk that Auset used to conceal her husband, Ausar's, body from Set in Egyptian mythology.

The four cross bars on the pillar mark the four cardinal points, giving it both religious and magical significance. The djed pillar was worn as a protective and strengthening amulet. It was often placed on a necklace with protective animals, the ankh, and the Eyes of Ra and Heru together. Ancient magicians likely included the djed pillar in magical scripts, especially if invoking hostile deities or beings. By stating that he possessed the pillar, the magician claimed to possess Ausar's backbone, which frightened unworldly beings into submission.

This amulet was made from various materials. The tomb of Queen Weret, dating of the 12th Dynasty, contained elements of a bracelet she wore which included the djed pillar inlaid with carnelian, turquoise, and lapis lazuli. You can shape your amulet from any material, or draw it onto papyrus. It can be worn or used in magical scripts to acquire stability, endurance, and strength.

Eye of Heru (Moon Eye)

The Eye of Heru was a common amulet in ancient Egypt, and is worn as a pendant today. In Egypt, it was called the wedjat and is worn to bring blessings of strength, vigor, good health, and luck to its owner. Above all, it is an awesome symbol of protection. In mythology, Set injured the lunar eye of the sky god, Heru. Tehuti, with his great intelligence and magic, restored Heru's eye so that it represented totality and health. (In other papyri it is Het-heru who restores Heru's eye).

Eyes were very important to the Egyptians. They believed that the eye was the mirror of the soul. An Evil Eye was the opposite of the Eye of Heru. It mirrored deceit, bad intentions, and threatened immanent danger. The power of the Eye comes from Heru, who maintains a role in Egyptian magic as a victim and a savior. He offers his power to humanity for defense, healing, and to establish order. Heru was represented by a falcon. It is believed that his right eye was the solar eye, and his left eye was the lunar eye. Together, the eyes create a powerful, indestructible amulet. (See the illustration of the pectoral amulet, below.)

The archetypal amulet was the wedjat eye. Scribes of magical papyri often instruct that it should be drawn on papyrus or linen as a temporary amulet. Funerary ceremonies include spells for charging the Eye of Heru to protect and empower the deceased. Magical scripts have spells for using the Eye to protect the magician, and to seek out the identity of thieves.

The Eye of Heru was usually made from lapis lazuli, jasper, silver, wood, porcelain, camelian, and, in some cases, it was plated with gold. The lunar eye, or an amulet of both eyes, may be worn to acquire amuletic power or drawn on papyrus in magic.

Pectoral Amulet

More complex and decorative amulets were made by incorporating different symbols together on one piece or jewelry, or in a magical drawing. You can combine the amulets herein to create your own powerful amulets for use in your magic. Above is an example of a pectoral from a 12th Dynasty necklace. This pectoral is said to come from Dahshur in Egypt and is now kept at Eton College in Windsor.

In the pectoral's center is a representation of the goddess Bat, who personifies the sistrum of Het-heru. To her left is Heru, represented as a sphinx. To her right is Set, who appears in an unknown animal form. Curiously, the two gods are unified as allies to protect the royal owner of the pectoral, instead of in their mythological roles as enemies. On Bat's head is the Sun disk guarded by the Edjo and Nekhbet cobras, or uraei. On each side of the disk are the eyes; on the left is the Eye of Heru and on the right, the Eye of Ra.

Thousands of individual and combined amulets existed in ancient Egypt. There are amulets that depict limbs and organs of the human body. The fist, hand, and finger amulets probably derive from magical gestures. Amulets were used in medical spells, including decrees that named the ailing parts of the body and commanded them to become well. The Egyptians even used incised seals as amulets. These were commonly in the form of scarab beetles and were used to seal chests, boxes, and documents. In magic, scarab seals were used in written magic to symbolize divine authority and protect magicians from harmful forces. Some Egyptian amulets survive to which we cannot assign a specific magical use. These may always remain a mystery, perhaps to be revealed only by devoted, contemporary magicians.

1 I E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic (New York: Dover, 1971), p. 26.

2 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995), p. 108.

3 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, p. 179.

4 Barbara Watterson, Gods of Ancient Egypt (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985). p. 93.

5 Time-Life Books Editors, TimeFrame 3000-1500 BC; The Age Of God-Kings (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1987), p. 71.

6 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, p. 61.

7 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, p. 49.

8 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, pp. 42-53.

9 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, p. 37.

10 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Book of the Dead (New York: Dover, 1967), p. cxix.