CHAPTER TWO

Ritual Tools

un-sen uat enen pert em re-k

They open the ways [for] that

which cometh forth from thy mouth.

Artifacts found and identified in tombs have offered us knowledge of many of the magical items used by royalty and priesthoods. The work of archaeologists and Egyptologists allows us to recreate of the magical tools that flourished in ancient Egypt. The treasures found in tombs had spiritual and magical purpose. Many were used by both the living and the dead.

In this chapter you will learn of many ritual tools—divination and magical tools such as magical figures, pictures, oils, and statues. You can make them for your personal use. Illustrations and instructions will help you to make them correctly. This chapter also defines magical implements, which you have the freedom of using as desired. You will learn their Egyptian use in the divination and magical formulas of chapter 5 and chapter 6. There was no manual of strict use for any particular ritual tool in Egypt.

The best-known ritual tools are associated with funeral ceremonies, as described in The Egyptian Book of the Dead. The tools described below were used by the living, as described in ancient magical papyri. Egyptologists and researchers learned from papyri that many implements were used in religious and magical ceremonies. We do not know, however, precisely how each was used. As there is no way to be certain of traditional use, you must use your own intuition and creativity.

Divination Tools

Egyptians scryed primarily by fire, oil, and/or water. Additional items that had symbolic value to the magician were incorporated into the rituals. Some tools have no known definition or understood purpose, however. Below, a definition and purpose of each tool is provided, followed by instructions for making or obtaining the tool.

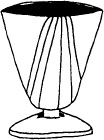

Oil Lamp

The Egyptian magician favored divination by lamp. Divination lamps were required to be white and free from any red color,1 although earthenware and terra cotta lamps of red color were used to make offerings and served other purposes in magic. The white divination lamps were made of various substances. Alabaster, finished to a beautiful, smooth white surface, was a popular substance. In certain divination formulas, bronze lamps were indicated.

Lamps were always used in dark, secret places. Only clean wicks were used, and real oil was placed inside the lamp. By Egyptian rule, the lamps were forbidden to touch the ground, so they were often set upon crude bricks on the ground. Magicians sat before the lamp or bent over it to fire scry. Scribes often gave helpful hints in their formulas; one such hint was for the magician to lie down on a reed mat before the lamp, with his head to the south and his face turned to the north, along with the lamp.

Another option was to fill the lamp with oil, tie it with four threads of linen, and hang it on a peg of bay wood on an eastern wall in the room in which magic would be worked.2 The magician would then insert a clean wick, light it, and stand before the lamp for divination.

A lamp of this type would be difficult for you to make or obtain. You can purchase a simple oil lamp, however, that has a round vessel to hold the oil and apparatus at its mouth to insert a linen wick. Linen for wicks is available at many fabric stores. A more modern oil lamp—with a hurricane chimney—would also work very well.

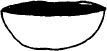

Vessel

A clean bronze cup or a new vessel of pottery was traditionally used. This was filled with water and, once the water settled, Oasis or vegetable oil was poured on top of the water. Oil was also used alone. The vessel was often used in conjunction with the lamp. The lamp shed light upon the oil when divination was conducted in a private, dark place.

Vessels of bronze are not common today, but they can be purchased at stores carrying fine china dishes and other household accessories. Pottery vessels are easier to acquire. To make your own, you can visit any craft shop for a pottery kit. There are clay and earthenware kits available, and some can be baked in your home oven.

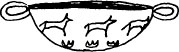

Bowl

The bowl was used the same way as the vessel. Most were made of bronze and were frequently used with water for scrying. A figure of the god or goddess invoked in divination was often engraved inside the bronze bowl. Typically, this was the god Anpu. Words of power and magical names were often engraved on the outside of bowls. To use a bowl in divination, you need to understand a piece of Egyptian history regarding its use: Of all the Egyptians skilled in working magic, Nectanebus, the last native king of Egypt (c. B.C. 358), was the best known—at least, if we may believe Greek tradition.3 His works were translated into Arabic, Syriac, Pehlevi, and many other languages and dialects. Famous as a magician and a sage, Nectanebus was deeply versed in Egyptian lore. He was adept at interpreting omens, sending created dreams to other individuals, procuring dreams, casting nativities, predicting the future of an unborn child, and in all magic. Indeed, he was considered a lord of the Earth, able to rule all kings by his magical powers. He created divination and magical script using a bowl of water. Unfortunately, no texts survive to state the material of which the bowl was made.

Nectanebus used the bowl of water in magic to defeat enemies, arriving by ship. He made wax figures of both enemy ships and men, and his own, then uttered invocations of the gods, winds, and subterranean demons. His wax figures came to life and battled. As enemy figures sank to the bottom of the bowl, Nectanebus thought his enemies would descend to the bottom of the sea. And in fact, he was successful in defeating many enemies and reigning for a considerable period of time.

From descriptions in E. A. Wallis Budges Egyptian Magic, we learn how Nectanebus prepared for his magical work. He retired to a private chamber and retrieved the bowl, which he kept especially for such purpose. He filled the bowl with water, put on the cloak of an Egyptian prophet, and held an ebony rod in his hand. Thereafter, the script was recited and the magic work done.

Bricks

Egyptian bricks were crude and were used as the principal building material, as well as in divination. The bricks were set upon the ground and were used as a base for the lamp, vessel, or bowl. Sand was sprinkled under the bricks for purification and to add magical influence. The magician often sat on a brick while scrying. When another person, a medium, was used as the seer during divination, the medium would sit on bricks and the magician would recite the formula over his or her head.

Researchers are uncertain why the Egyptians felt it necessary to have both the scrying tool and the seer positioned off the ground. It is known that the priesthoods and magicians were extremely disciplined concerning purity in all magical work. That alone may be the reason. Later, burned bricks, introduced by the Romans in Byzantine times, were used for the same purpose.

You can easily purchase a couple of new bricks rather than attempting to make them. Home and building centers carry a variety of bricks. Sand, gravel, and stone dealers can be found in your telephone book yellow pages and may offer a selection, usually at better prices.

Censer

Censers were often used in worship, divination, and magic in Egypt. Clay, earthenware, or bronze censers (or braziers) held burning incense. Olive-wood charcoal was used to burn the incense.

Today, you can purchase a censer made of these materials, or you can handcraft your own clay censer by purchasing a kit sold in craft stores. Olive wood is difficult to obtain, but may be found through herb farms or herb mail-order companies. The charcoal tablets commonly sold in New Age shops will work as a substitute.

Incense

Egyptians traded for and purchased their incense from a town called Punt, near Somalia. Egyptian priests and magicians used different types of incense, but frankincense and myrrh were preferred. Ancient incense was used in resin form only. Incense sticks and cones were not used. You can buy resin incense today from New Age shops and mail-order companies. (See Egyptian Resources, page 217.)

Oil

Egyptians found that oil was better for scrying than water alone because its surface did not distort easily and disrupt the magician's concentration. Cedar, Oasis, and vegetable oils were used for divination. Scribes suggested that the oil was added to the dish gradually to avoid it becoming cloudy. The oil had to be as clear and free of debris as possible.

Cedar oil is made from the dried wood. Today, the Atlas cedar and red cedar are used to make essential oil. The oil can be found at any shop selling essential oils or herbs. You need a lot of it for scrying, so it may be costly. (NOTE: Pregnant women should not use cedar oil). Vegetable oil is readily available to you and can be found in your local grocery store.

Oasis is described in papyri as “real oil,” however, no other definition is given. The word oasis describes a place in the desert that is fertile due to the presence of water. It may be that standing water that had absorbed minerals and plant debris over time was taken from such places in Egypt. The debris would have given the water an oily texture.

Eye-Paint

This liquid was handmade and placed into the eyes in order to see the gods during divination. The Egyptians used several recipes—some including the blood or gall of particular animals, herbs, and plants. It is not known exactly how the eye-paint worked. It may have caused distorted vision, allowing the magician to see deities, beings, or creatures conjured in divination and magic. There may also have been a drug effect in certain recipes.

How to Make Greek Bean Eye-Paint: In magical papyri, there are several recipes for making eye-paint. Most recipes are not practical or considered safe for our use today. One such recipe involves pounding a hawk's egg with natural myrrh (not incense). Obviously, both ingredients are not easily obtained today and knowledge of how to properly make or store such a potion is unknown.

The recipe below is found in The Leyden Papyrus. The scribe who recorded the recipe wrote that it had been “tested” and was “excellent.” You will need a supply of Greek bean plant, also known as “raven's eye.” This can be found where lupine, a plant of the pea family, is sold. Usually, it can be purchased at herb farms, through herb retailers, and at some garden centers that sell vegetable seeds or plants.

- Take the fresh flowers of the Greek bean plant and put them in a clean glass bottle. Stop the mouth of the bottle tightly and leave it in a secret dark place for twenty days.

- After twenty days, remove the bottle and open it. You will find that the flowers resemble testicles with a phallus. Close the bottle tightly and leave it in the dark place for forty days.

- When you open the bottle after forty days and look inside, you will find that the contents have become blood-colored. Your eye-paint is ready to use. You can leave the bloodlike liquid in this glass bottle, but it must be stored in a hidden place at all times.

Eye-paint is not necessary and was not always employed in divination. Before using this eye-paint, you should determine that you are not allergic to the plant.

Knots

Knot or cord magic, used in folk magic or early witchcraft, originated in Egypt. Instructions for these techniques are detailed in various magical papyrus.

How to Use Knots in Divination: In The Leyden Papyrus, Col. III, page 39, there are instructions for making an amulet of knots for the purpose of working divination and magic quickly. Because a live scarab is not easily obtained in our Western world, I have omitted its use in the instructions below. You will need 16 individual linen threads, each approximately a foot long (4 white, 4 green, 4 blue, and 4 red), and a drop of personal blood.

- Take the 16 individual threads of linen and make them into one band.

- Stain the band with a drop of your blood. Women can use menstrual blood. Be careful to use a sterilized pin or other instrument for drawing your blood.

- Bind the band to some part of your body, such as your arm, before divination or magic.

This amulet is to be bound to whomever has the vessel and wants it to work magic quickly.

Writing Ink

Many plant dyes and natural dyes were used as ink for writing on papyrus. A popular choice was the juniper plant, whose juice was a favorite of the Egyptians and the Greeks. A reed pen, made from the plants shoots, was used to apply the writing inks. Reed pens are not practical today, although some companies in the appendix may supply them. Quill pens and sable paintbrushes are natural writing utensils that can be substituted. In chapter 3 you will learn how to make and use the tools of ancient scribes, including further information about writing ink.

Reed Mat

Reed mats were used primarily during worship for the priest or priestess to kneel upon, and during divination for the magician to sit or lie upon while communing with the gods or other invoked beings. After reciting the divination formula—through which a shift of consciousness occurred—in some instances, the magician would lie down on a reed mat in a trance state or fall asleep to receive answers to his or her inquiries.

Reed is actually a general term used to describe various types of grasses with jointed, hollow stems. Rustic musical pipes were made from the reed stem, and long strips of reed were woven together to make the ancient mats.

Making a reed mat takes great skill. Finding such a mat is very difficult. You may contact sources of Egyptian wares listed in the Egyptian Resources section, of this book to find out if they can recommend a source for these mats today, or you can use a woven mat available commercially.

Kohl-Stick

Unfortunately, not much is known about this wooden ritual staff. In The Leyden Papyrus it is described as “the stick oí satisfaction,” which indicates its use in acquiring satisfying results in divination and magic. Col. XXIX, 1.27 of this same papyrus describes preparation instructions for a magician in which a kohl-pot and kohl-stick are used to pound together the ingredients of an herbal and organic potion. It is possible that the kohl-stick served as a pestle. In Col. X, there are instructions for the magician to bind the kohl-stick to his waist, and then to travel to an elevated place outdoors, in daylight, opposite the Sun, for Sun divination.

To make a kohl-stick, obtain a fallen tree branch to serve as a ritual staff. Strip the bark from it, and decorate it as desired.

Constellations

Astrology was practiced in Egypt as a practical and magical art. Egyptians observed that certain constellations were visible on the horizon at night, allowing them to tell time by the position of a particular constellation in the sky at a given hour. Scribes drew up tables that recorded the readings for the purpose of telling time and working magic.

The Shoulder constellation, also called “The Great Bear” in Egypt and known to the English-speaking world as Ursa Major, consists of seven stars. Since seven is a sacred Egyptian number, it is no wonder that this constellation was used in magic. From The Leyden Papyrus, we learn that, for best success, a divination formula was recited seven times, at night, opposite the Shoulder constellation, on the third day of the month.

The same papyrus instructs magicians to set up their divination materials in a dark recess, then venture outdoors into the night to stamp the ground with their foot seven times, and then recite the opening charms of any divination script to the Foreleg/Great Bear constellation. Then the magician must turn to the north seven times and retreat to the dark recess to begin the actual divination inquiry.

In chapter 5 you will learn of additional readily available items used in divination, such as a wooden table.

Tools for Magic

Tools used in divination were also used for magical work. Remember, the Egyptians considered divination to be magic, not a separate subject, as tends to be the case in contemporary practice. Ritual staffs, the sistrum, the menat, gold rings, water, figures, pictures, statues, minerals, wreaths, earthenware dishes, lamps, oils, and even constellations are used in both divination and magic. Some items, such as the menat, had symbolic uses and were meant to be held or carried by a priest, priestess, god, or king.

Ritual Staffs

In Egypt, there were not many trees, or many different types of trees, so wood was very valuable to them and highly regarded. Although there was an abundance of stone, wood was scarce. It was used to make magical rods and as the core of many statues. Egyptians traded with foreigners for exotic wood, which is probably why they delighted in making and using countless wooden ritual staffs.

Many sizes, shapes, and types of carvings were used in the manufacture. It is impossible to * know the precise use for each staff or rod, but Egyptologists have gained ideas through deciphering hieroglyphs. One type, the Was-Scepter or Uas Staff, was traditionally made of heti wood. This staff was forked at the bottom and carved at the top to resemble the head of an animal. The J top is often called a “canid,” and resembles the god Anpu, with long carved ears.

There are pictorials of gods holding this staff. Ausar, as the night Sun, was always represented as a mummy holding the scepter, crook, and flail. The Uas staff is a staff of divinity and royalty. There are instances in which a priest is shown holding this staff, suggesting it was used in religious and magical ceremonies. It was not common for priestesses to carry this staff. Priestesses carried the sistrum and menat, which you will learn more about later in this section.

Figure 8. Animal head-shaped top of Uas staff.

How to Make a Uas Staff: The Uas staff is not difficult to make. You will need a fresh tree branch (not rotted), approximately five feet long, with a forked bottom. It should be at least an inch and a half to two inches in diameter to allow you to carve the angle that supports the animal head at the top. In addition, you will need a rectangular piece of wood approximately six inches long and four inches wide, a pencil, a chisel, a hammer, a C-clamp or vise, a worktable, a hand saw (keyhole or coping), and wood glue.

- Strip the bark from the tree branch and check it for rotted areas.

- Secure the branch to a worktable using a C-clamp or a vise.

- Use your chisel and hammer to chip wood at a 90-degree angle from one side of the staff top. This creates the angle upon which the animal head will be affixed. There is no right or wrong length for the angled surface. When finished, remove your staff from the worktable.

- Take the smaller piece of wood and with the pencil, draw a narrow and simple animal head that consists of a long snout and two flattened ears. (See figure 8, page 46.)

- Secure the wood with drawing to the worktable. Following your pattern, use a coping or keyhole saw to trim away the extra wood to form the animal head.

- If desired, carve out a prominant groove between the two, flattened ears using the chisel and hammer.

- Remove the animal head from the worktable and secure your staff there. Affix the animal head to the staff's angled top with generously applied wood glue. Clamp the head into position and allow the glue to dry overnight.

Woodworking requires caution, time, and patience. Perfection is not necessary, so do not become frustrated.

When you have carved the design of the head, you have achieved the traditional appearance. You can use a small pocketknife to whittle finer details into the wood if desired.

Crook

This short wooden staff was held by gods, pharaohs, and certain priests, symbolizing sovereignty and dominion. Priests and priestesses both carried the crook during worship rituals, magical ceremonies, festivals, and other rites.

It was traditional for the crook to be held in the right hand of both royal and priestly men and women. Men held the crook in their J right hand, usually holding the flail in their left—often in the Ausar position, with arms crossed over the chest. Priestesses held the crook casually at their right side and carried the lily scepter held against their chest with their left hand.4

Magician's Rod

This is a general term given to numerous short wooden staffs that were held in the left hand by magicians and priests when performing magical rites. The typical magician's rod was made of bronze, with one end finished in the fans and head of a cobra. The entire staff length depicts a cobra, representing the god of magic, Heka, or his female equivalent, the goddess Weret Hekau, who was usually shown in cobra form.5 The god Heka is pictured in funerary papyri as a human man holding two of these snake-shaped rods criss-crossed over his chest, suggesting that the Egyptians thought highly of the rod's practical use.

Exactly how this rod was used in magical rites is unknown. We do know that these rods were used as emblems of the magician's control over the gods, creatures, and beings he invoked, or evoked, during magical work. Often consisting of glazed steatite, these rods were hollow and made in sections that were ingeniously fit together. The sides of the rod were decorated with lamps, baboons, crocodiles, lions, the Eye of Heru, and other protective symbols. The figure of a turtle, thought to be unclean but useful to protect against harmful forces, was likely attached to the top end of the rod. Presumably, the magician held control of the protective and aggressive power of the creatures decorating the rod to use as he desired.

In another example of the numerous magical rods employed by magicians, the last native-born ruler of Egypt, Nectanebo, waved an ebony rod to invoke gods and devils to defeat animated wax models of his enemies and their ships.

Lily Scepter

It is uncertain if this scepter, carried by ladies of royalty and priestesses, was an actual lily stem with flower, or made of wood. Certain pictorials of priestesses carrying the scepter suggest it was made of wood, while others show a leaning, flexible material that indicates the use of a real lily.

The lily scepter was held in the left hand of the priestess, and the crook was held in her right. She hugged the scepter to her chest as she walked through the temple and carried out her various duties and magic.

The process by which to make this scepter is unknown. You may choose to use a real lily in your magic. Lily bulbs are inexpensive and you can plant lilies around your property to beautify your yard, as well as provide materials for a practical ritual tool.

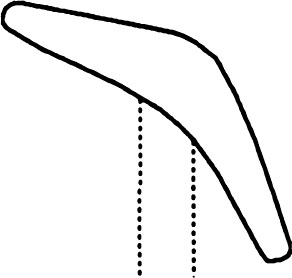

Wand

The wand was sometimes called the “magic knife,” but is best described as an apotropaic wand. Its primary function was to turn away evil, particularly evil spirits. Unlike the stick wand used in modern pagan practices, this wand was boomerang-shaped, with a curve like a crescent moon, and flat, like a throwstick. Flocks of wild birds symbolized the forces of chaos in Egyptian art, so the throwsticks used to kill or stun them could have symbolized the victory of order over chaos.6 For the magician, this wand served as a tool and an emblem of control over devils and powerful spirits.

The wands of approximately 2800 B.C. were made of ivory and etched with early representations of supernatural and divine beings. Later, wands were elaborately carved with pictures of numerous creatures and inscriptions. One rounded end of the wand might have a jackal head carved on it, while the other end might contain a lion or a panther head. Bulls, lions, snakes, scarab-beetles, crocodiles, and supernatural creatures like the griffin and the double sphinx were among the many chosen guardians and symbols of protection carved onto the wands.

The creatures who appeared upon the wands were fighters, brandishing torches and knives, and depicted strangling or stabbing serpents and other menacing beasts. Two of the most popular figures were Taweret, the hippopotamus goddess, and Bes, an ugly, stubby-legged dwarf with the mane and ears of a lion.

Some wands were custom made for a particular magician, and included an inscribed formula that vowed to protect its user against all enemies and dangerous beings encountered in magical work. A typical inscription might read:

Words spoken by these gods: We have come in order to protect the lady (or man) of the house, X.7

How to Make a Wand: To make this wand, you may use any type of wood, especially since ivory is undesirable and difficult to acquire. You will need a large square or rectangular piece of wood, a pencil, a jigsaw or band saw, a Dremel power tool or a chisel, gouge, and hammer for carving symbols and decorations, and some sand paper.

- With a pencil, draw the boomerang shape of the wand onto the piece of wood. Size is entirely at your discretion. Choose a size that you can grasp comfortably in your hand.

- Cut the shape of the wand with a jigsaw or a band saw. Be careful when using the power saw. Wear eye protection.

- Sand the edges of the wand to a round, smooth finish. Next, sand its surface smooth.

- You can carve or paint symbols and pictorials on the wand if you wish.

Use this wand during all evocations in your magical practice. Hold it in either hand and “throw” or whip it forward during an evocation to simulate the realistic throw of a throwstick. This gesture, coupled with your symbolic decorations and spell formulas, will ensure your success in conjuring unruly spirits.

Sistrum

Music played an important part in all temple rituals. One instrument used regularly was the sistrum, a kind of rattle that was sacred to the goddess Het-heru.8 The sistrum was held by gods, pharaohs, priests, and priestesses. Priestesses held it in their right hand, and the menat (discussed below) in their left.9

The sistrum was made of metal or faience.10 It resembled a Het-heru head, with its horns bent around to form a loop. Threaded through three holes on each “horn” were three thin metal rods. Each rod passed across the loop from one side to the other. Metal beads were sometimes placed upon the rods, which were left loose in their sockets so that, when shaken, the sistrum rattled.

How to Make a Sistrum: You can make your own sistrum by using the description and illustration. To do so, you will need a number of items sold in plumbing and hardware stores: three thin metal rods, each about two inches longer than the distance between the matching holes of the sistrum (these can be copper or any metal, even a coat hanger); a two-foot length of flexible copper tubing about ‘/2 inch in diameter to shape into a loop; a solid copper or brass pipe ten inches long and one inch in diameter.

You'll also need an adhesive for permanently joining metal piping together (ask the store clerk for his/her recommendation), some pliers, a power drill with a drill bit slightly larger in diameter than the three metal rods, a C-clamp or vise, a worktable, and some metal beads (to add more volume to the sound of the sistrum). Tell the hardware store clerk what you are making and ask for help in selecting your supplies. You may want to take along a picture of a sistrum.

- Bend the tubing into a loop that can be permanently affixed in the handle. Measure, as evenly as possible, where the three holes need to be placed on each side of the loop so that the rods rest loosely and are parallel. Do not place the three holes on either side too close together. Mark the drill targets on the metal with a black magic marker or a dab of paint.

- Lay the full length of copper tube on a worktable. Secure it to the table with a C-clamp or a vise.

- Drill the six holes completely through each marked target using a power drill and a drill bit slightly larger than the diameter of the metal rods. Be certain to have an experienced individual help you drill the holes safely. Have the tube properly secured as you drill. Do not hold the loop in one hand and drill with your other hand.

- Bend the loop and push its ends into the opening of the copper pipe/handle. If required, pinch the ends of the loop together with pliers to squeeze it into the handle. The loop will stay inside the handle once firmly fitted, but it is a good idea to secure it with adhesive. Apply the adhesive generously inside the handle and on the loop ends. Allow it to dry for a day or two.

- Place your metal rods into their holes as described above. With the pliers, bend each rod at a 90-degree angle on one end, and then pass the straight end through its first hole. If you wish to use metal beads, place them on the rod now.

- Slide the straight end through its other hole. Use the pliers to bend the end of the rod to a 90-degree angle, in the opposite direction from the other end. Do the same for the other two rods.

You have successfully created the ancient sistrum.

Menat

The menat was an object presented to the gods with the sistrum. A host presented it to guests at a feast. Priestesses held it in their left hand, with the sistrum in their right, at religious festivals and certain temple rituals. These two instruments were emblems of the priestesses' office.

The menat is often called “the counterpoise of a collar.” It consists of a disk with a handle attached and acord.11 It serves as a bead necklace with counterpoise to hang down the back of the wearer. The disk was made of faience, bronze, or hard stone, and was often inscribed with hieroglyphic words of power or adoration. The handle was usually made of bronze. It was worn around the neck, or carried in the left hand by its handle. As an amulet, it brought joy to its bearer. Used in temple ceremonies, it was believed to possess magical properties.

How to Make a Menat: The process of making a menat is unknown. We can speculate how to do so, however. Brass, copper, or bronze can be used as the handle. A circular piece of stone or bronze can serve as the disk. It may be a good idea to use bronze, copper, or brass for both the handle and the disk so they can be soldered together with a soldering gun for durability. In research, I found no instructions for attaching a stone disk to a bronze handle.

An assortment of colored or metal beads can be strung on strong necklace threads available at craft shops. The top of the handle will need to have two holes drilled in it, as discussed in the sistrum section above. The two holes should line up on either side of the handle top so that you can pass the necklace strand through the handle to secure it.

Keep in mind that the menat was worn around the neck. Do not make it too large or heavy if you intend to wear it in your ceremonies.

Figures

The Egyptians believed it was possible to transmit the spirit of a man, woman, child, god, or unworldly being into an inanimate figure or statue that then took on the qualities and attributes of that person or being. It was a common belief in Egypt that figures or statues possessed indwelling spirits of the people or beings they represented.

From Egypt, by way of Greece and Rome, the use of wax figures passed into Western Europe and England. In the Middle Ages it enjoyed great favor.12 If a cult decided to take over a temple belonging to another god or goddess, they would shatter any figures or statues of the deity so that the deity's spirit would no longer have a place to dwell, and would become powerless. The cult would then replace the figures with representations of their deity who would thenceforth reside in the temple in spirit and rule in power.

Symbolic ceremonies and the recital of words of power over figures brought the desired spirit and its powers to dwell in a figure. The spirit could then be used for both good and evil at the will of the magician. Magicians used wax figures to obtain their desires and succeed over their enemies. They also made provisions for the happiness and well-being of the deceased by making Shabti figures of servants and laborers out of various materials to aid the dead in the underworld.

Magical figures were primarily made of wax. The wax was purchased or homemade. When a situation presented itself, a mass of wax was whittled and shaped to look like the person or creature it represented. It was not necessary that the wax figures be life-size or even perfect in design. Magical formulas were recited over the figure to send its spirit into the objective universe to do the magician's will.

A Spell Using a Wax Figure: There were many spells employing wax figures. One, for the purpose of ridding oneself of an enemy, specifies that the magician must be washed and ceremonially pure. He writes in green color upon a piece of new papyrus the names of the enemy(ies), as well as those of the enemy's father, mother, and children. He makes a wax figure of the enemy and inscribes the enemy's name on the figure. The figure is tied with black hair and then cast upon the ground and kicked about with the left foot. Next, the magician pierces the figure with a stone spear head. Finally, the wax figure is cast into a fire. In chapter 6 you will learn magical spells that include the use of wax figures.

Aristotle's Use of Wax Figures: In the 13th century, an Arab writer, Abu-Shaker, wrote of the wax figures Aristotle had made from knowledge acquired of the Egyptian art. Aristotle gave Alexander the Great a box inside which several wax figures were nailed down. The box had a chain, so that Alexander could carry it wherever he traveled. Aristotle taught him how to recite magic words over the box whenever he set it down or picked it up. The box was not to leave Alexander's presence—even if it had to be specially carried by a servant.

The figures in Aristole's box represented the armed forces that opposed Alexander. Some of the figures held leaden swords, curled backward, in their tiny hands. Others held spears that pointed to the ground, or bows with cut strings. All the figures were laid face down in the box. Aristotle had learned from Egyptian magic that such figures assured that any armies who challenged Alexander the Great would be powerless.

Statues as Magical Figures: The magical use of statues was similar to that of wax figures. Temples had shrines on their walls in which a statue of the temple deity was placed. Statues were also placed on the altar to receive offerings. The statues of gods, along with their hieroglyphic inscriptions, served as talismans.

Statues were commonly made of wooden cores, black granite, tinted ivory, hollow bronze, faience, red granite, and quartzite. Wooden statues that were stuccoed, gold-leafed, or painted on the wood surface were most popular.

Queen Dalukah's Use of Magic Statues: A legend found in Les Prairies d'Or13 describes an undated event in ancient Egypt when the army of Pharaoh drowned in the Red Sea after a battle. The surviving women and slaves feared being attacked by the kings of Syria and by various western armies. They appointed a woman named Dalukah as their queen.

Dalukah was wise and adept at magic. Her first action was to surround Egypt with a wall that was guarded by men. Around the enclosure, she placed stone figures of crocodiles and other threatening animals. Dalukah also made figures of the Syrian, western, and nomad tribesmen, as well as of the beasts they rode upon. If an army came from any part of Syria or Arabia to attack Egypt, the queen recited words of power over the figures of the soldiers riding their beasts, and they immediately disappeared underground. The same fate befell the living creatures the figures represented.

Queen Dalukah reigned for thirty years, proving the power of her sorcery. She collected plants, animals, and minerals, and learned the secrets of the attracting or repelling powers of nature. These collected items, along with her magical figures, she placed in many great temples.

Pictures

The Egyptians drew and painted pictures depicting gods, divine beings, and all of life. Picture-writing graced the exterior of buildings, while pictures covered the interior of temples, royal structures, and tombs. Pictorials were also engraved into stone. When words of power were recited over a picture, the spirit(s) of the subjects in the picture were summoned to dwell within it and could be influenced to assist in magical aims.

The magical papyri in which formulas survive that use magical pictures each have different words of power. The instructions for creating and charging magical pictures were quite varied. You can create your own pictures and the words of power to accompany them for magic.

Cippus of Heru—A Famous Picture: The most famous picture of Egyptian magic is the Cippus of Heru (otherwise known as the Metternichstele), which was found in 1828 at the construction site of a Franciscan monastery. Although the exact date of the stele is unknown, it is thought to have been produced between 378 B.C. to 360 B.C. The picture is a gigantic talisman engraved with magical gods and beings, and words of power. Every god, demon, animal, and reptile of importance is depicted upon it.

It is thought the Egyptians made and used many Cippus. A Cippus was placed in a conspicuous area of the home, courtyard, or any building to protect its inhabitants from hostile beings, both visible and invisible. Its power was believed to be unconquerable.

Using Pictures in Magic: You can fashion such a picture for your own needs. You can choose simply to draw Egyptian gods, creatures, and other beings onto papyrus, your lamp wick, or white paper. If stone carving appeals to you, try to make a Cippus. You do not need artistic expertise to design magical pictures. There was never a rule that all pictures had to appear in a certain way, or be perfect. Part of the mystery in Egyptian magic is that each depiction of the deities, people, and creatures was unique. Your art work should reflect how you know the deities and other creatures in your mind's eye.

If you choose to draw pictures on papyrus, use the writing ink described in this chapter and in chapter 3. In chapter 6, certain magical formulas provide instruction for using magic pictures.

Knot Magic

There are many uses of linen knots in magic. Sometimes knots were used to bind a person, situation, or creature. In this instance, untying the knots was as vital a stage in casting the magical spell as initially tying them. Knots were used to prevent something from happening until the desired time or to catch and bind harmful spirits for disposal or for the magician's use.

Knotted cords and any use of knots is associated with the god Anpu, who, through his role in mummification, rules both binding and wrapping. In Graeco-Egyptian papyri, the knots used in magic were indeed called Anpu threads. The red hair ribbons of the Seven Het-herus, the sevenfold form of the goddess Het-heru, were used to bind and gain control of dangerous spirits. The ribbons were also used in love spells. (You will learn of the Seven Het-herus later in this chapter.) In a Graeco-Egyptian papyrus, the magician ties 365 knots in black thread, saying each time, “Keep him who is bound.”14

Use linen knots in your magic as described above. Chapters 5 and 6 have spells that include instructions for using knots.

Gold Rings

Gold rings were used, especially in love spells. I have not included the original instructions for their use in this chapter, or later in chapter 6, because some ingredients that are not practical—such as the heart and gall of a shrew-mouse—are required.

In one formula, the embalmed tail of the shrew-mouse is pounded with myrrh and placed inside a gold ring. How this feat was accomplished is not known. After placing the ring onto a finger and reciting charms over it, any individual that the magician touched with the hand submitted to his/her desires. Another formula called for the heart of a shrew-mouse to be set within a seal-ring of gold. Such a ring was believed to bring favor, love, and reverence. Seal-rings were engraved with a picture and served as amulets. Not all had animal organs inserted. You will learn how to use these rings in chapter 3.

Water

The Egyptians sprinkled the floor with water for the reception of visitors in the home, or when opening ceremonies in the temple. Water was recognized for its cleansing properties and was used to purify. Ancient Egyptians also visited buildings inside the district of a temple to drink or bathe in consecrated, holy water for healing. The water would also procure healing or prophetic dreams. Both uses can easily be incorporated into your magical practice.

Oil

In magic, different oils were used to achieve particular magical aims. From The Leyden Papyrus we learn of the following uses:

- To conjure a damned spirit to do your bidding, take an old wick and place clean butter in your lamp to burn during the conjuring. (The Egyptians used butter as an oil in this example.)

- To work love magic, place rose oil onto a clean wick and burn it in your lamp. Recite chosen words of power to charge it. (For love magic spells, see chapter 6.)

- Cedar oil was often used to anoint the forehead before working magic, and in some instances, during religious rituals.

Also from The Leyden Papyrus, the following blessing of oil is recited before using it. It is appropriate for healing and other forms of magic:

Thou being praised, I will praise thee, O oil, I will praise thee, thou being praised by the Agathodaemon; thou being applauded by me myself, I will praise thee forever, O herb-oil—otherwise true oil—O sweat of the Agathodaemon, amulet of Seb. It is Auset who makes invocation to the oil. O true oil, O drop of rain, O water-drawing of the planet Jupiter which cometh down from the sun-boat at dawn.

The Agathodaemon is an almighty four-faced daemon—the highest darkling in Egyptian mythology.15 This is not to suggest that the oil used in Egyptian magic was evil or negative. It simply means that oil contained great power for use in whatever way the magician chose.

Herbs and Minerals

Herbs were used particularly in healing magic. The problem of defining what herbs and minerals were frequently used and how they were used, has been a struggle for even the most scholarly Egyptologist.

The Egyptians had their own names for plants and minerals. Translators of papyri have been able to identify some of these, but generally list them as vocabulary with little notation on how each was used.

Herbs: Chamomile, paeonia, rush-leaf, saffron, rue, houseleek, plants of the fennel family, wild garlic, and pepper were used in medicine. The use of herbs in Egypt was probably similar to their use in the herbal medicine of today.

Herbs and plants were also used to fashion wreaths, which were sold by wreath sellers and made by magicians to project magical properties. Mention of wreaths placed upon altars at funeral ceremonies can be found in The Egyptian Book of the Dead. There is also brief mention in magical papyri that wreaths were placed on shrines and altars during certain temple ceremonies.

Saffron is a plant with purplish flowers and orange stigmas that yielded orange-yellow dye and seasoning from its dried stigmas. It served as a dye for clothing, and possibly as a writing ink.

Minerals: Many magnetic minerals were used in medicine and magic. Magnetic iron ore and magnes mas are two magnetic minerals frequently used. It is assumed that the Egyptians harnessed the magnetic forces of the Earth by employing such minerals in magic.

Native sulphur and other minerals were sometimes mixed together with herbs to alleviate the pain of gout. Natron is a mineral of hydrous sodium-carbonate, which was used for embalming the dead and in some magic formulas. It was heated with other salts and spices, then mixed with honey for embalming.

Salt was not often used in spells, which is interesting, since it played such a crucial role in Egyptian life, agriculture, and death. Chapter 5 includes a sample divination setup in which lumps of salt are employed. This is the only formula of its kind found in my research.

Altar

Elegant altars, decorated with plants, lotus flowers, liberation vases, haunches of beef, fish, loaves of bread and cakes, vases of wine and oil, containers holding beer and wax, a wreath, fruits, and various cut flowers, were used during funeral ceremonies and in temples. While elaborate altars were not used in divination, they were used during certain religious and magical rites.

Altars served as places to present offerings to the deities. At the close of rituals or magical rites, the perishable food items were eaten by the priesthood. This was not a formal ceremony in itself, but rather a time of casual and social dining.

Storage of Implements

Magical implements were often stored in special boxes. The great priestly official, the kher heb, was so much in the habit of performing acts of magic that he kept a box of materials and instruments always ready for the purpose.16

During the 19th Dynasty, it became popular for priesthood members to store their magic utensils in niches in the wall. These niches could be in the magician's private study, where he wrote and conducted magic spells, or within a temple. The east wall is commonly specified in papyri as the place to build such a niche. Once the niche was built, it also acted as a wall altar. The magician either removed materials to conduct divination or magic elsewhere, or worked at the niche itself, using it as an altar.

You can place your journals, magical tools, and other materials into similar storage areas. Certainly, the first is the most practical.

1 F. L. Griffith and Herbert Thompson, eds., The Leyden Papyrus: An Egyptian Magical Book (New York: Dover, 19741, p. 44.

2 E L. Griffith and Herbert Thompson, eds., The Leyden Papyrus, Col. XXVII, p. 159.

3 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic (New York: Dover, 19711, p.91.

4 Lionel Casson, The Pharaohs, in Treasures of the World Series (Chicago: Stonehenge, 198 1). p. 142.

5 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995), p. 11.

6 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, p.40.

7 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, pp.42.

8 Barbara Watterson, Gods of Ancient Egypt (New York Facts on File Publications, 1985), p. 127.

9 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Book of the Dead, p. 245.

10 Barbara Watterson. Gods of Ancient Egypt, p. 127.

11 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Book of the Dead, p. 245.

12 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, pp. 97, 98.

13 B. de Meynard and P. de Courteille, eds., Les Prairies d'Or (Paris,1863), tome ii, p. 3981.

14 Geraldine Pinch, Magic in Ancient Egypt, p. 83.

15 E L. Griffith and Herbert Thompson, eds., The Leyden Papyrus, Col. IV, 1.17.

16 E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, p. 70.