CHAPTER SIX

When Addison Mizner decided to leave California for New York in 1904, it was a time of unprecedented confidence and expansion in America. By the turn of the century, the population had reached seventy-five million, a remarkable increase of 50 percent in just twenty years.1 In the last decade of the century, America ceased looking inward and began to develop a more aggressive foreign policy that would quickly establish it as a world power. In the span of six years just before Mizner’s arrival in New York, America had annexed Hawaii and gained control of the territories of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. It had also assumed responsibility for the Panama Canal project from the French, a move that included not only authority for its construction but also ownership of the actual canal property. A thriving America was beginning to look beyond its borders.

This expanded horizon had implications not just for American culture and society but especially for Addison Mizner. Shifting attitudes among the elite created an ethos that facilitated his acceptance into polite society and paved the way for him to become a society architect. Growing prosperity created a leisure class that began to enjoy its wealth and took gratification in displaying it. The social customs of English and French aristocrats informed the tastes and habits of the newly affluent Americans and induced them to demand sophisticated symbols of prosperity to publicize their grandeur. These trends began in New York and continued, despite the interruption of World War I, in Palm Beach, and each city played an integral role in the development of the young architect.

The ramifications of an expanded perspective were profound for society, especially in America’s largest city at the upper echelon. After the Civil War, New York society was composed of the Knickerbockers, the original English and Dutch settlers, for whom intellect, propriety, and courtesy were important touchstones.2 Into this static Knickerbocker culture soon came individuals, emboldened with new fortunes and brazen aspirations, whose conflicting values posed a challenge to the existing social structure. As the Gilded Age was concerned with achievement and mobility, its greatest representatives avidly sought inclusion into the upper reaches of New York society.

This portrait of Caroline Astor by the French painter Carolus-Duran shows the confidence of a wealthy woman who was the social arbiter of New York society after the Civil War. Known simply as “Mrs. Astor,” she codified appropriate behavior and worked to integrate the traditional Knickerbocker society with wealthy arrivistes who represented “new money.” As a result, many ladies who would befriend Addison Mizner became acceptable in polite society.

Courtesy of Wikipedia. Portrait by Carolus-Duran.

The newly created fortunes that invaded New York’s Knickerbocker aristocracy in the Gilded Age were derived through industry and pluck as well as cunning and deceit. Mark Twain spoke of the greed and corruption of the times in 1871, “What is the chief end of man?—to get rich. In what way?—dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must.”3 The nouveaux riches attempted to penetrate existing society through extravagance and display, practices condemned by old New York aristocracy. Until the younger generation of Knickerbockers, led by Caroline Astor, began to include families of new money in its world in the 1880s, the only way to permeate the aristocratic caste was by marriage into one of the venerable families.

Economist Thorstein Veblen commented on the importance of “conspicuous consumption” as a means of elevating one’s social status. In his view, the mere presence of consumption and leisure was not sufficient. What was more important was the recognition of their presence by others: “In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men it is not sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence.”4 Veblen also observed that anyone striving to advance one’s position emulated the characteristics of his superiors. The arrivistes understood the effective use of emblems of status and sought not just to emulate the magnificence of their superiors but to surpass them. The new conception of culture then developing in New York was constructed not so much on an appreciation of the arts but on an outward manifestation of wealth through architecture and the arts.5

The resolution of this struggle between old and new money fell to the redoubtable and capable Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, the wife of William Backhouse Astor Jr., known later in life simply as Mrs. Astor. Recognizing the need to accommodate a changing society, she created new standards that united the old guard with the most worthy of the nouveaux riches. Beyond creating a powerful coalition between a static aristocracy and the more dynamic entrepreneurs, Astor wanted to create an identity for American society that would redound to the credit of the young nation. The late nineteenth century was a period of nationalism, and all countries were involved in establishing traditions that reinforced and enhanced perceptions of national identity. The more aristocratic cultural standards that Mrs. Astor was endeavoring to establish were to serve as a calibration against which America could be measured favorably against any nation.

With a codification of behavior that became the social catechism of the elite, New York society arrived at a satisfying synthesis in the 1880s. It was then infused with new blood but still anchored to the existing tenets of propriety and good taste. This remained a burnished, privileged world generally inimical to foreigners and arrivistes, a microcosm that grew “from within rather than from without.”6 Mrs. Astor was the unchallenged arbiter who had presided over a personally anointed collection of socialites called The 400.7 She was aided in regulating the beau monde by her acolyte Ward McAllister and, together, they represented a barrier to those regarded as inferior or unworthy. According to many, Mrs. Astor had transformed society into a “secular religion.”8

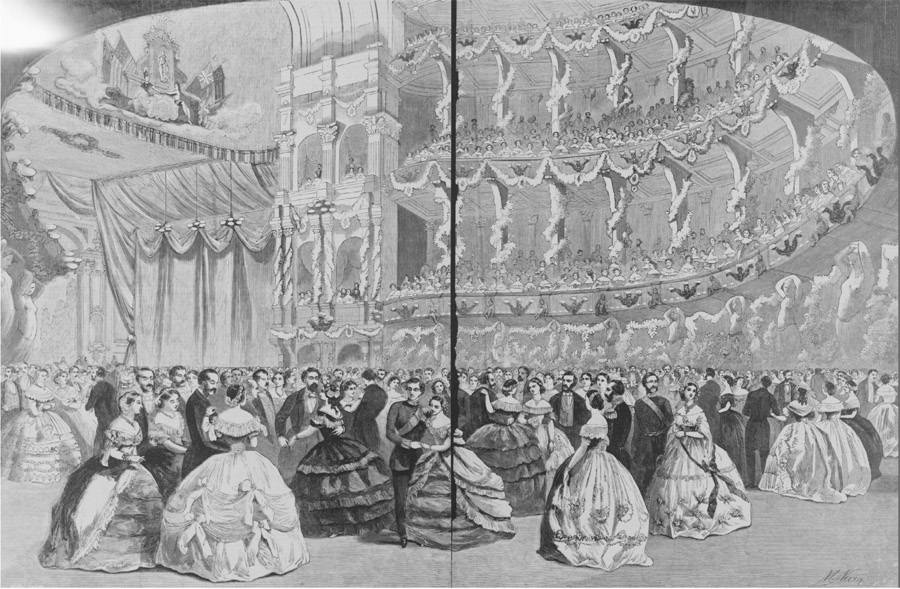

One of the factors that prompted a shift in the perceptions of New York society was a growing familiarity and fascination with Old World aristocracy. In the fall of 1860, New Yorkers thronged along Broadway to glimpse Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, in his open carriage. The occasion was special as this was the first time a member of the British royal family had visited North America. He was feted everywhere and was the guest of President James Buchanan in the White House. On the evening of October 12, approximately five thousand people squeezed into the Academy of Music to attend an exclusive ball given in his honor.9 This constituted the prince’s first exposure to American women, an attraction that was warmly reciprocated. Despite marriage to a Danish princess in 1863, the prince led a lusty life until his death in 1910. The lavish attention he bestowed on women would have implications for young Americans.

This illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts the grand ball at the Academy of Music in New York on October 12, 1860 to honor the visit of the Prince of Wales to the United States. The prince, who would become King Edward VII in 1901, was greeted by large crowds everywhere. After the civil war, wealthy Americans began to emulate English social customs and many had their daughters married into the English aristocracy. These changes brought about a demand for grand architectural statements, some of which served to educate Addison Mizner.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Young ladies from many of America’s richest families became a focal point in English society beginning in the 1870s. British aristocrats had historically derived their wealth from landed estates and typically shunned involvement in industrial ventures. Due to a depression in agriculture in the 1870s and a shift in wealth creation from farming to industry, many peers of the realm found themselves impoverished and saw their wealth eclipsed by industrial entrepreneurs. Many needed an infusion of cash to preserve family estates that required enormous upkeep. This coincided with the desire of many American nouveaux riches, some excluded from Mrs. Astor’s tight circle, to have their daughters married to Old World nobility. This begat a spate of convenient alliances that prevailed during the Gilded Age when the glamorous and rich daughters of America became known as Dollar Princesses.10

The Prince of Wales and his fashionable set, finding these American young ladies more independent than English girls, welcomed them to London society. The prince introduced Jennie Jerome, the daughter of financier Leonard Jerome, to Lord Randolph Churchill, the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, and their subsequent marriage became one of the best known of the Anglo-American alliances. Consuelo Yznaga, descended from Cuban and Natchez families who were plantation owners, was an important member of the prince’s intimate circle and became through marriage Lady Mandeville, later the Duchess of Manchester. This trend would continue in the 1890s with many other unions, two of which involved Mary Goelet becoming the Duchess of Roxburghe and Consuelo Vanderbilt the Duchess of Marlborough. As duchesses, these daughters of the young American republic were now positioned at the very summit of the venerable British aristocracy.

The marriage of Consuelo Vanderbilt to the 9th Duke of Marlborough was engineered by the bride’s socially ambitious mother, Mrs. William Kissam Vanderbilt, born Alva Erskine Smith in Mobile, Alabama. Introduced to her husband by her best friend Consuelo Yznaga, Alva recognized in Vanderbilt a convenient way to escape the devastation of the post–Civil War South.11 Not only did Alva name her sole daughter after her childhood friend but identified in Consuelo Yznaga’s ducal rise a model of social elevation for her own daughter. Such an advantageous transatlantic union would not only guarantee a prominent position in society for the daughter but would greatly enhance that of the mother as well, a circumstance that held great appeal to Alva.

Alva Vanderbilt was an important catalyst of social change during the Gilded Age. The shifts she initiated would have significant implications for Addison Mizner when he moved to New York in 1904. Not only did she finagle admittance to the impermeable world of Mrs. Astor’s 400 but, at the turn of the century, she brought about a more relaxed style of entertaining to society. Like other members of the elite who had begun to adopt English and Continental habits, she was a pioneer in cultivating a lifestyle that embraced a country house as the natural complement to a city residence. An important patron of architects, she built several iconic homes that also precipitated shifts in style and design.

Alva Vanderbilt possessed the financial means and cleverness to confront New York’s nobs in order to have her family elevated to the social firmament of New York. In 1875 Alva married William Kissim Vanderbilt, the grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt and son of William Henry Vanderbilt. Following the death of Commodore Vanderbilt two years later, William Henry Vanderbilt and both of his sons filed plans to build new houses on Fifth Avenue. Alva’s and William’s splendid new French chateau at 660 Fifth Avenue was unlike the new homes of other Vanderbilts and contrasted significantly with existing New York brownstone mansions.12 To celebrate the completion of the house in the winter of 1883 as well as to commemorate the visit of her childhood friend, Lady Mandeville, Alva scheduled a party for March 26, the Monday after Easter. This would be the first important social event following six weeks of Lent.13 More aggressively, Alva chose to give a costume ball, an entertainment that invited the derision of proper Knickerbocker society as it was thought to encourage disreputable behavior. Finally, as Monday nights were traditionally reserved for Mrs. Astor’s reception of guests in her home, Alva had thrown down the gauntlet to the arbiter whose rule of social New York at this time was absolutely unassailable.

The residence of William K. Vanderbilt at 660 Fifth Avenue, circa 1883. Alva Vanderbilt worked with her favorite architect, Richard Morris Hunt, to design the “Petit Chateau,” a limestone house in the French Renaissance style. It was distinctly different from the brownstone houses that surrounded it. Alva conspired with Hunt to build imposing houses in New York, Newport, and on Long Island. Addison Mizner would have experienced them all.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Excitement built for the ball as all wanted to see the splendid house that cost a fortune and to experience the luxurious entertainment promised by the hostess. To her great consternation, Mrs. Astor found that neither she nor her daughter Caroline were among the one thousand who were invited. This was not an oversight by Alva Vanderbilt but a conscious omission owing to social protocol. It was also a brilliant stratagem. Because Mrs. Astor considered the railroad fortune of the Vanderbilts distasteful, she had never introduced herself to them, an acknowledgement that would have signaled social acceptance. Without this overture, etiquette prevented Alva from extending an invitation to someone who had not formally recognized her. Aware of the prospect of an inconceivable snub to her daughter, Mrs. Astor immediately dispatched a calling card to Alva at 660 Fifth Avenue, whereupon an invitation was delivered to the Astor residence farther south at 350 Fifth Avenue. Alva’s glorious ball had the effect of finally bringing the powerful women and their important families together.

At the end of the ball, Alva Vanderbilt, dressed as a Venetian princess by Charles Frederick Worth in Paris, took great satisfaction in the success of the evening, and triumphant pleasure in engineering Vanderbilt acceptance into the highest echelon of society.14 This event had the effect of highlighting a transformation in New York society. Alva Vanderbilt and Lady Mandeville, childhood friends from the South and formerly Knickerbocker outsiders, stood this evening as social equals of the most formidable representative of New York society. These new initiates had pursued different paths to the pinnacle of acceptability: Alva Smith moved to New York and managed to penetrate the social inner sanctum with cleverness and wealth while Consuelo Yznaga went to London and achieved the same with charm and a title.

The Petit Chateau, the imposing new house where the Vanderbilt ball took place, represented a departure from the conventions of Gilded Age New York. The chateau’s architectural style was designed by Richard Morris Hunt, the first American graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and its façade and elaborate interiors were a reflection of Alva’s affinity for French design.15 Clad in dressed limestone and capped by a steeply pitched, copper-crested roof, the asymmetrical structure had a slender tourelle that reached high above a façade of four floors. The interiors were sumptuously decorated with period French furnishings such as Gobelin tapestries and distinctive furniture by renowned ébénistes. This curated approach encouraged a taste for French design and decorative art in the Gilded Age.

Alva Vanderbilt, the wife of William K. Vanderbilt, is dressed in an evening dress by Charles Frederick Worth for the stunning masquerade ball she hosted to introduce New York society to her new townhouse on Fifth Avenue in 1883. Alva well understood the importance of architecture in the quest to advance her social position among the elite and collaborated with Richard Morris Hunt to do so.

Courtesy of Wikipedia. Photograph by Jose Maria Mora.

As Alva Vanderbilt had astutely recognized, the most conspicuous and effective advertisement of wealth and taste was a grand mansion, a traditional architectural statement that, by its magnificence and scale, suggested lineage and tradition like the great ancestral homes and chateaux of England and France. That such houses could present compelling evidence of a family’s worthiness to be accepted into the highest ranks of society created a demand for the services of the city’s most sophisticated architects: Richard Morris Hunt; McKim, Mead & White; Carrère and Hastings; and others. As the neighborhood of the wealthy extended beyond the Knickerbockers’ Washington Square, it moved northward on Fifth Avenue, a long boulevard offering unrestrained possibilities for grand statements like Alva Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau.

Comfortable yet unhappy, Alva Vanderbilt took an unusual step. In an age when divorce was unthinkable and scandalous, she astounded New York society in 1894 by separating from her husband, William K. Vanderbilt, and divorcing him a year later.16 With a generous divorce settlement, she subsequently married Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont, a socialite and good friend of her former spouse. Continuing to demonstrate her fascination for architecture, she began to redecorate the interiors of Belmont’s Newport mansion, Belcourt, and commissioned Hunt & Hunt to design a neoclassical townhouse at 477 Madison Avenue in New York. In 1897, she had the same architect design and build Brookholt, a neoclassical mansion in East Meadow, Long Island. Finally, after the death of her husband, Alva Belmont had Hunt’s sons build Beacon Towers, a new Gothic country house completed in 1918 in the village of Sands Point on Long Island.

Attuned to the social significance and symbolism that accompanied grand architectural statements, others were also familiar with the traditional custom in England where aristocrats simultaneously maintained country houses and London townhouses. Eager to emulate English and European tastes, Americans at this time began to build magnificent country houses on Long Island where Addison Mizner would spend much of his time. Creating great estates by consolidating Long Island farms, the newly wealthy New Yorkers began to hire the best architects to design large houses with all manner of stables, garages, workshops, and agricultural buildings. These families also were expected to have a house in Newport, a camp in the Adirondacks, a place for a few weeks in Saratoga, and a winter hideaway in the South.

One of the early examples of a country house on Long Island was Idle Hour, a house in the Queen Anne style set on nine hundred acres in Oakdale, a privileged hamlet in the town of Islip. Built in 1878, this was the first of many collaborations between Alva Vanderbilt and William Morris Hunt, whom she befriended just after her marriage in 1875. When Alva Vanderbilt wanted a “summer cottage” in fashionable Newport, Rhode Island, she turned once more to her favorite architect. Again, the result of Vanderbilt’s and Hunt’s collaboration represented innovation. The elegant and elaborate Marble House, a Beaux-Arts structure completed in 1888, heralded a shift in attitude from the simple clapboard and shingle houses to the large stone mansions that define much of Bellevue Avenue today.

The material result of America’s prosperity and social ambition was an array of magnificent mansions and country houses that provided Mizner with a cosmopolitan supplement to his extracurricular education. Through old friends and their superb connections, the architect was able to experience many of the best examples firsthand. Into the peak of this enormous pre-war expansion of domestic architecture stepped Addison Mizner, aspiring to become a society architect and eagerly anticipating life in America’s greatest city. Shifting attitudes in society conveniently created a receptive environment for a bohemian, unconventional outsider that put him on a path to realize this dream.