‘PARKER’S CROSSROADS’ TO THE MEUSE RIVER

STARTING POINT: THE JUNCTION OF N30 WITH N89 30 KILOMETRES NORTH OF BASTOGNE AND JUST OFF N25. LOOK OUT FOR THE CRIBA PLAQUE AND 105MM HOWITZER ON THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF THE CROSSROADS IN MEMORY OF THE DEFENDERS OF ‘PARKER’S CROSSROADS’.

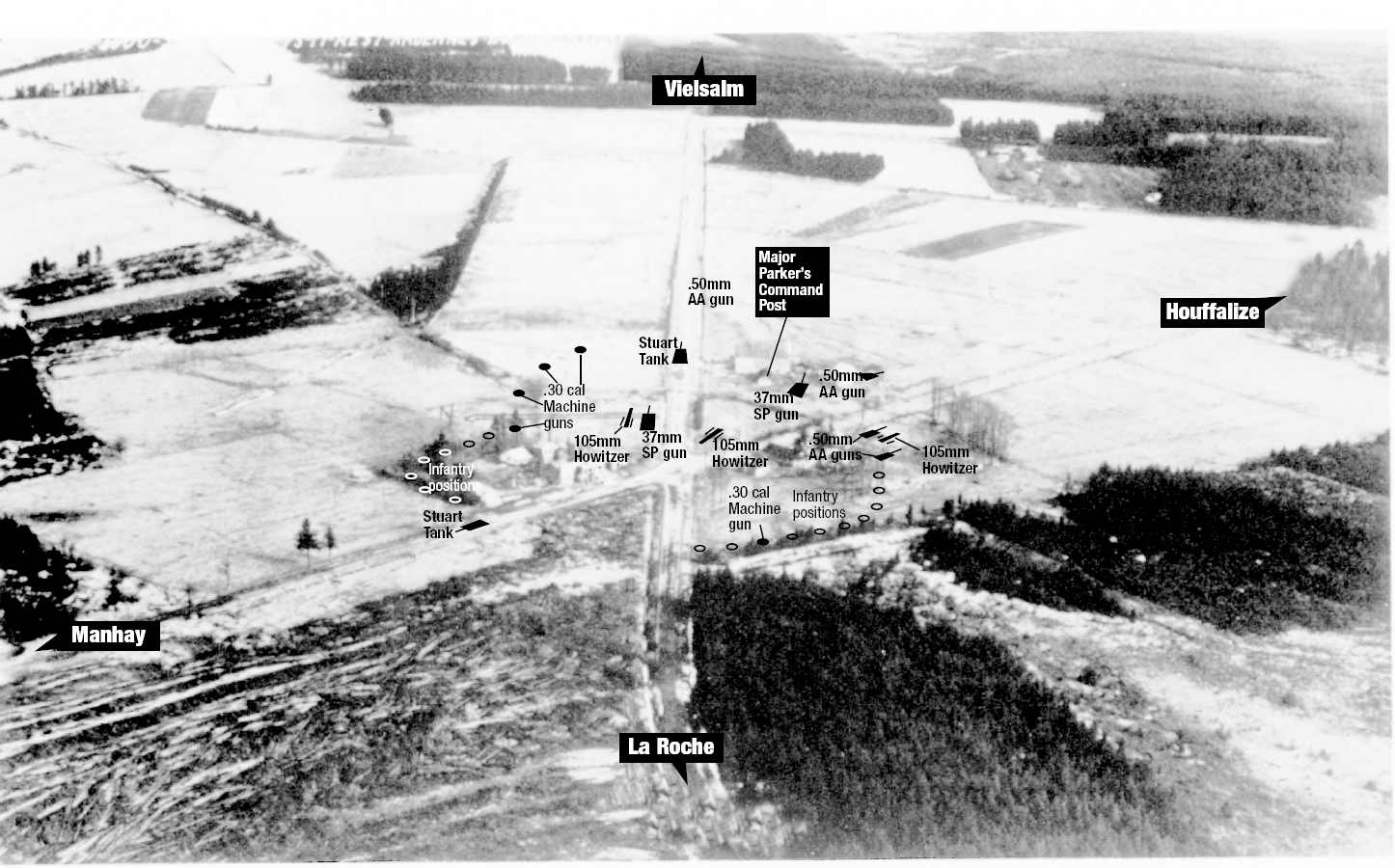

Baraque de Fraiture was and still is a handful of buildings at the crossroads south of the Belgian hamlet of Fraiture. The crossroads stands on one of the highest summits of the Ardennes, a small shelf or tableland at an elevation of 652 metres (2,139 feet). The roads, which intersect, are important. N30 (then N15) the north-south road, was then the through paved highway linking Liège and Bastogne. N28, (now N89) the east-west road, was then classed as a secondary road but was nevertheless the most direct route for movement along the northern side of the Ourthe River, connecting for example, St. Vith with La Roche. In 1944, the crossroads and its few buildings were on cleared ground, but heavy woods formed a crescent to the north and west, and a fringe of timber pointed at the junction from the Southeast. In the main, the area to the south and east was completely barren. Here the ground descended, forming a glacis for the firing parapet around the crossroads.

Parker’s Crossroads where a 105mm howitzer faces southeast.

The tactical stature of the Baraque de Fraiture intersection was only partly derived from the configuration of the roads and terrain. The manner in which Major General Mathew B. Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps had deployed its units in the initial attempt to draw a cordon along the northwest flank of the German advance was equally important.

The mission assigned three task forces of the US 3rd Armored Division had been to close up to the Bastogne-Liège highway (with the crossroads as an objective), but it had not been carried out. East of the same highway the 82nd Airborne Division had deployed, but with its weight and axis of advance away from the crossroads. Circumstance, notably the direction of the German attacks from 20 December onwards, left Baraque de Fraiture, and with it the inner flanks of the two divisions, to be defended on a strictly catch-as-catch-can basis. On the afternoon of 19 December, Major Arthur C. Parker III, successfully led three 105mm howitzers of the ill-starred 589th Field Artillery Battalion out of the melée on the Schnee Eifel east of St. Vith and here to Baraque de Fraiture. His mission was to establish one of the roadblocks that remnants of the 106th Infantry Division were preparing behind St. Vith.

The CRIBA plaque upon which the Belgians commemorate their American liberators. (Author’s collection).

The next day, four half-tracks mounting .50 calibre machine guns arrived from the 203rd Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion, now moving in with the 7th Armored Division to establish the defensive lines around St. Vith. That night, for the first time, the crossroads’ defenders heard the sound of vehicles moving off to the southeast. (They probably belonged to Oberst Rudolf Langhaeuser’s 560th Volksgrenadier Division, which that afternoon captured Samrée off to the southwest).

Before dawn, an eighty-man enemy patrol came up the road from Houffalize and the American Anti-aircraft gunners cut them apart whereupon they identified the dead and prisoners as belonging to the 560th. Among them was an officer of the 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer Division, scouting out the route of advance for his incoming division. In the afternoon, Troop D of the 87th Cavalry Squadron, earlier dispatched by the 7th Armored Division to aid Task Force Orr of 3rd Armored Division in a projected counterattack at Samrée, came in to join the crossroads garrison. The Troop leader had gone into Dochamps to meet Lieutenant Colonel William T. Orr of Task Force Orr, but finding Germans in town, disposed his men and vehicles under orders from General Hasbrouck of 7th Armored, that the crossroads must be held.

Fog settling over the tableland in late afternoon, gave the enemy a chance to probe the crossroads’ defenses, but these jabs were no more than warning of things to come. Meanwhile, eleven tanks and a reconnaissance platoon from Task Force Kane of 3rd Armored Division arrived on the scene. The Americans spent the night of 21 December ringed around the crossroads; tanks alternating with armored cars in a stockade beyond which lay the rifle line. There was no sign of the enemy despite reports from all sorts of sources that German armour was gathering at Houffalize. Messengers coming in from the headquarters of the 3rd Armored and 82nd Airborne Divisions, all brought the same message: ‘Hold as long as you can!’

Major General James M. Gavin, commanding the 82nd Airborne, was especially concerned by the threat to his division’s flank developing at the crossroads and went to talk the matter over with the 3rd Armored commander, Major General Maurice Rose at Rose’s command post in Manhay. General Rose assured Gavin that his troops would continue to cover the western wing of the 82nd Airborne. Gavin nevertheless acted at once to send his 2nd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, from his division reserve to defend Fraiture, the village on a ridge +/- 1,300 metres northeast of the crossroads position. In addition, having made a personal reconnaissance of the area, Gavin ordered the regimental commander, Colonel Charles Billingslea, to dispatch a company of his glider infantry to reinforce the crossroads’ defenders. The 2nd Battalion reached Fraiture before dawn on 22 December and Captain Junior R. Woodruff led Company F into the circle around the crossroads just before noon. This slight reinforcement was negated when Task Force Kane withdrew its tanks to stiffen the attack going on in front of Dochamps.

Oberst Rudolf Langhaeuser Commander 560th Volksgrenadier Division. (Author’s collection courtesy General Langhaeuser).

Both sides spent the day of 22 December in waiting. The 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer Division had more than its fair share of fuel supply problems and was moving in fits and starts. Mortar fire laid on by the German reconnaissance screen left in the area as the 560th Volksgrenadier Division advanced northwest, from time to time interrupted movement in and out of the crossroads position. That was all. During the day the 3rd Armored Division received some reinforcements; these were parcelled out across the front with a platoon from the 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion going to the crossroads. Enroute south from Manhay on the night of the 22nd, the tank destroyer detachment lost its way and halted some distance north of the crossroads. German infantry surprised and captured the platoon in the early morning. Already Das Reich was moving to cut off and erase the crossroads garrison. Attack was near at hand, a fact made clear when the defenders captured an officer patrol from 2nd SS Das Reich at dawn near the American foxholes.

At daylight, shelling increased at the crossroads as German mortar and gun crews went into position; yet the long awaited assault failed to materialise due to lack of fuel. The 2nd SS Das Reich had only enough gasoline to move its reconnaissance battalion on 21 December for commitment near Vielsalm.

General der Waffen-SS Willi Bittrich, Commander 2nd SS Panzerkorps in the Ardennes. (Courtesy General Bittrich).

Late that evening, an exploding mortar round seriously wounded Major Parker. He initially refused evacuation but upon losing consciousness was sent to the rear. Major Elliott C. Goldstein, also of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion, then assumed command of the crossroad’s defenders. Throughout daylight on 22 December, 2nd SS waited in its forward assembly areas till early evening when enough fuel arrived to set SSObersturmbannführer Otto Weidinger’s 4th SS Der Führer Panzergrenadier Regiment, some tanks and an artillery battalion moving. In the course of the night the panzergrenadiers relieved the small reconnaissance detachments of the 560th, which had been watching at the crossroads and filed through the woods to set up a cordon west and north of the Baraque de Fraiture. SS-Obersturmbannführer Weidinger had placed a battalion to the right of the main north-south highway, and another battalion deployed around and to the rear of the crossroads.

Obersturmbannführer Otto Weidinger, 4th Regiment Der Führer of 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich at Baraque de Fraiture. (Courtesy Otto Weidinger).

In the pre-dawn darkness of 23 December the first move came, as the 2nd Battalion of the 4th SS Der Führer Panzergrenadier Regiment made a surprise attack on Fraiture only to be driven back after a bitter fight by the defending glider infantrymen.

Having lost the element of surprise, the Germans settled down to hem in and soften up the crossroads defense. They took radios from captured American vehicles and used them to jam the wave band on which the American forward observers were calling for fire. Whenever word flashed over the air that shells were on their way, enemy mortar crews dumped shells on American observation posts – easily discernible in the limited perimeter – making sensing virtually impossible. Late in the morning, Lieutenant Colonel Walter B. Richardson, who had a small force backing up Kane and Orr near Dochamps, sent more infantry and a platoon of tanks toward the crossroads. By this time, the German panzergrenadiers occupied the woods to the north in sufficient strength to halt the foot soldiers. The American tanks impervious to small arms fire reached the perimeter at about 13.00, whereupon the rifle line pushed out east and south to give the tankers a chance to manoeuvre.

A German soldier on Reconnaissance armed with an MP44 assault rifle. (Courtesy Roland Gaul)

At the crossroads time was running out. Shortly after 16.00, the German artillery really got to work, for twenty minutes pummelling the area around the crossroads. Then, preceded by two panzer companies (perhaps the final assault had awaited their appearance), the entire rifle strength of the 4th SS Der Führer closed upon the Americans. Outlined against the newly fallen snow, the line of defense was clearly visible to the panzers and the Shermans had no manoeuvre room in which to back up the line. The fight was brief, moving to a foregone conclusion. At 17.00 the Company F commander asked Billingslea for permission to withdraw; but Gavin’s order was still ‘Hold at all costs.’ Within the next hour the Germans completed the reduction of the crossroads defense, sweeping up prisoners, armoured cars, half-tracks and the three howitzers. Three American tanks managed to escape under the veil of halflight. Earlier they had succeeded in spotting some panzers that were firing flares, and knocked them out. A number of men escaped north through the woods; some got a break when a herd of cattle stampeded near the crossroads, providing a momentary screen. Company F of the 325th Glider Infantry suffered the most but stood its ground until Billingslea gave permission to pull out. Ultimately, forty-four of the original one hundred and sixteen who had gone to the crossroads returned to their own lines. Drastically outnumbered and unable to compensate for weakness by manoeuvre, the valiant defenders of what today is known as ‘Parker’s Crossroads’ had succumbed like so many other small forces at other crossroads in the Ardennes.

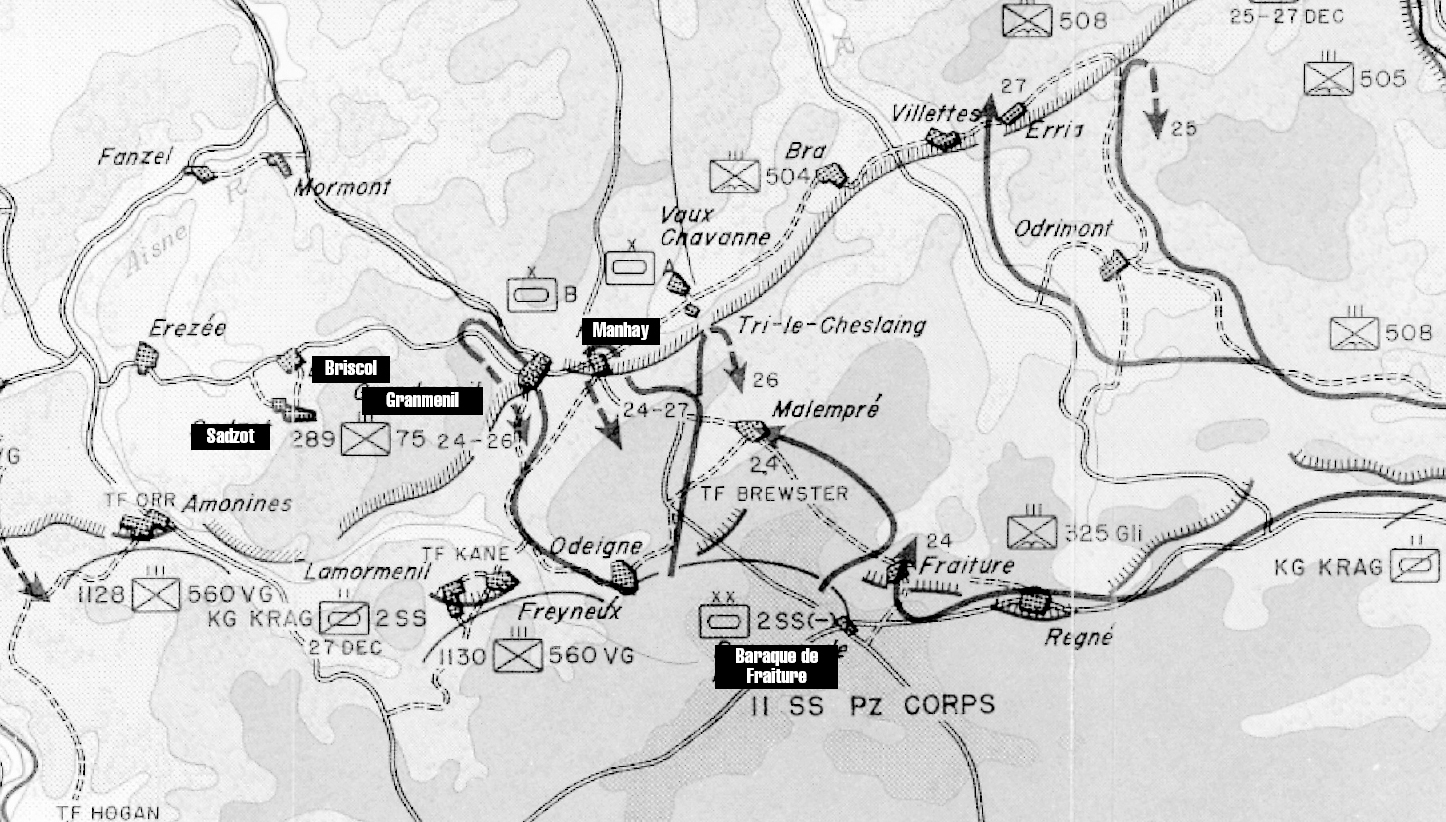

The dent made here at the boundary between the 3rd Armored and the 82nd Airborne Divisions could all too quickly turn into a ragged tear, parting the two and unravelling their inner flanks. The next intersection on the road to Liege, at Manhay was only four miles away to the north. From Manhay, the lateral road between Trois Ponts and Hotton would place the Germans on the deep flank and rear of both divisions. General Rose and General Gavin reacted to this threat at once; so did General Ridgway. Order followed order, but there remained a paucity of means to implement them. The deficit in reserves was somewhat remedied by the troops of the 106th Division and 7th Armored who, all day long, had been pouring through the lines of the 82nd Airborne after the hard-fought battle of St. Vith. General Hoge of CCB 9th Armored had been told at noon to send his 14th Tank Battalion to bolster the right flank of the 82nd. One tank company went to the Manhay crossroads; the rest moved to Malempré, two miles to the Southeast and off the Liege highway. Coincident with the German attack at Baraque de Fraiture, General Hoge received a torrent of reports and orders. By this time Hoge wasn’t too sure as to either his attachment or mission. He finally gathered that the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads had been lost and CCB was to join the defense already forming to the north at Manhay.

Drive north of Baraque de Fraiture on N30 stopping at the first sign to the right for ‘Malempré with open fields to both left and right.

On their way to Manhay, the attacking Germans initially bypassed Task Force Brewster of 3rd Armored Division here at Belle Haie. With the enemy now behind him Major Olin F. Brewster, the task force commander radioed for permission to pull out to the east in the direction of Malempré in the hope of finding it still to be in American hands. The advancing Germans knocked out two of Brewster’s tanks whereupon he ordered his vehicles abandoned and released his men to find the American lines on their own – most of his command made it.

Continue north on N30 stopping in Manhay just before the road leading left (N807) toward Grandmenil (signposted at crossroads as 806 to Marche. N807 splits from N806 a few hundred yards down this road). The street running southwest of the crossroads leads to the ‘Maison Communale’ (Town Hall), in front of which stands a memorial to the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division.

The XVIII Airborne Corps mission as of 19 December 1944, was to block any further German advance along an irregular line extending from the Amblève River through Manhay and Houffalize to La Roche on the Ourthe River, placing the corps’ right boundary twenty miles northwest of Bastogne. Three threatened areas were known to be in the newly assigned zone of operations. The Amblève River sector, where the 30th Infantry Division’s 119th Infantry was deployed and the Salm River sector, especially at Trois Ponts where unknown to the 82nd Airborne, Company C of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion still barred the crossings.

The third of these was the general area north of the Ourthe River where a vague and ill-defined German movement had been reported. The German capture of Houffalize had served to cut the main Bastogne-Liége highway N15 (Today N30) and their subsequent capture of ‘Parker’s Crossroads’ gave them direct access north to Manhay – a distance of 6.4 kilometres. Manhay not only sat astride the main road to Liége but also the principal east-west road from Trois Ponts to Hotton. Major General James M. Gavin’s 82nd Airborne Division therefore sent a company of its 325th Glider Infantry here to Manhay on the evening of 19 December 1944. On 20 December, Task Force Kane of 3rd Armored Division took up positions at Malempré, about 3,000 metres Southeast of Manhay. The village of Manhay represented a tactically untenable position. Hills to the east and west dominated the village, and to the Southeast extensive woods promised cover from which the enemy could bring fire on the crossroads. By reason of the ground, therefore, Malempré, on a hill to the south beyond the woods was the chosen objective. Task Force Kane reached Manhay then pushed advance elements as far as Malempré without meeting the enemy.

By dawn on 24 December Gruppenführer Heinz Lammerding’s 2nd SS Das Reich stood poised to attack north of the Baraque de Fraiture toward Manhay. Lammerding planned to attack with his armoured infantry regiments to either side of the N15. The fuel problems he was having meant that although both groups possessed small panzer detachments, the bulk of his tanks remained bivouacked in wood lots to the rear. The terrain ahead was only negotiable by small groups of armour and they had to husband their fuel for a short, direct thrust.

SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Lammerding.

Tanks of 2nd Armored Division and infantrymen of the 75th Infantry Division intermingle at an Ardennes road junction. (US Army Signal Corps).

The initial attacks made by the 1130th Regiment of the 560th Volksgrenadier Division against Lamormenil and Freyneux proved disastrous with the attackers suffering severe losses.

During the night of 24 December, the Americans began rationalizing their over-extended lines by pulling the 82nd Airborne Division back to a much shorter front extending diagonally from Trois Ponts southwest to Vaux Chavanne, just short of Manhay. CCA of the 7th Armored Division was to withdraw to the low hills just north of the village and Grandmenil while retaining a combat outpost in Manhay itself. (Colonel Rosebaum, its commander protested to the effect that the high ground now occupied by his command south and Southeast of Manhay was tactically superior but without result).

The series of American manoeuvres begun on Christmas Eve proved both difficult and tricky to co-ordinate, particularly in the Manhay sector. Communications were not yet thoroughly established and tactical cohesion had not yet been secured. Communications between the 3rd and 7th Armored Divisions failed miserably. There had been so many revisions of plans, orders and counter-orders during 24 December, that Colonel Rosebaum didn’t receive word of his new retrograde mission until 18:00. The withdrawal of CCA, 7th Armored and the elements of CCB, 9th Armored, south and southeast of Manhay was scheduled to begin at 22:30 – and most of these troops along with parts of 3rd Armored would have to pass through Manhay.

On the night of 24 December, the main body of Das Reich began moving toward Manhay. The seizure of Odeigne the previous night had opened a narrow sally port facing Grandmenil and Manhay, but there was no road capable of handling a large armoured column between Odeigne and the 2nd SS Panzer assembly areas south of the Baraque de Fraiture. On 24 December the commander of the 3rd SS Deutschland Panzergrenadier Regiment secured Lammerding’s permission to postpone a further advance until German engineers could build a road through the woods to Odeigne. By nightfall on Christmas Eve engineers completed the road and Allied fighter-bombers had returned to their bases.

The village of Manhay showing signs of the heavy fighting which took place here on Christmas Day 1944.

The 3rd SS Deutschland Panzergrenadier Regiment now gathered in attack formation in the woods around Odeigne, while tanks of the 2nd Panzer Regiment formed in column along the new road. To the east the 4th SS Der Führer Panzergrenadier Regiment sent a rifle battalion through the woods toward Malempré. By 21.00, the hour set for the German attack, the column at Odeigne was ready. Christmas Eve had brought a beautifully clear moonlit night; the glistening snow was hard-packed and tank going good.

About the time the German column started forward, the subordinate commanders of CCA, 7th Armored Division received word by radio to report here to be given new orders – the orders that is, for the general withdrawal north.

The commander of the 7th Armored position north of Odeigne (held by a company of the 40th Tank Battalion and a company of the 48th Armored Infantry Battalion) had just started for Manhay when he saw a tank column coming up the road toward his position. A call to battalion headquarters failed to identify these tanks, but since the lead tank showed the typical blue exhaust fumes of a Sherman, it was decided that this must be a detachment from the 3rd Armored Division. Suddenly, a German Panzerschreck rocket blasted from the woods where the Americans were deployed; German infantry had crept in close to the American tanks and their covering infantry. Four of the Shermans fell victim to enemy panzerschrecks in short order and two more were crippled, but the crippled tanks and one still intact managed to wheel about and head for Manhay. The armored infantry did likewise.

A thousand metres or so further north stood another 7th Armored roadblock, defended by an under strength rifle company and ten medium tanks which had been dug in to give hull protection. Again the enemy-crewed Sherman leading the German column deceived the Americans. When almost upon the immobile American armour the Germans cut loose with flares. Blinded and unable to move, the ten Shermans were so many sitting ducks. German tank fire hit most of them as their crews hastily evacuated their vehicles. The American infantry in turn fell prey to the attacking panzergrenadiers moving through the woods bordering the road and fell back in small groups toward Manhay.

It was now a little after 22.30, the hour set for the 7th Armored move to the new position north of Manhay. The covering elements of 3rd Armored had already withdrawn without notifying CCA of the 7th. The light tank detachment from Malempré had left the village (the grenadier battalion from Der Führer moving in on the tankers’ heels) and the support echelon of CCB 9th Armored had already passed through Manhay. The headquarters column of CCA 7th Armored was just on its way out of the village when the American tanks that had escaped from the first roadblock position burst into the village. Thus far the headquarters in Manhay knew nothing of the German advance – although a quarter of an hour earlier the enemy gunners had shelled the village. A platoon commander attempted to get two of his medium tanks into positions at the crossroads itself, but the situation quickly degenerated into a sauve qui peut when the leading panzers stuck their snouts into Manhay. Confusion reigned supreme as panzer ace SS-Oberscharführer Ernst Barkmann’s Panther number 401 raced at top speed into the village, he and his crew thinking they’d been left behind by the rest of their platoon. They arrived in Manhay to find the place full of American vehicles and the road to the west occupied by three Shermans. Barkmann decided to head north of Manhay passing several enemy tanks as his Panther roared up the main street. Crushing an American jeep and colliding with a parked Sherman, Panther 401 knocked out a pursuing Sherman then sought shelter in the woods north of the village.

SS-Oberscharführer Ernst Barkmann.

Meanwhile the fighting raged in Manhay and in a last exchange of fire, the Americans accounted for two of the panzers but lost five of their own tanks at the rear of the CCA column. Thus Manhay passed into German hands. As the sounds of the battle died down, Barkmann and his crew drove slowly back down the road into Manhay passing numerous burning vehicles to rejoin their comrades.

Turn west (left on the N806) in the direction of Grandmenil and, driving up the main road (N807), keep an eye out for a bus stop on the right beside which stands a Panther tank of the 2nd SS. Diagonally across the main road from the tank is a monument to the 289th Infantry Regiment of the 75th Infantry Division, the 3rd Armored Division and a plaque to the 951st Field Artillery Battalion, VII Corps, 1st Army.

On the main street in Beffe, two curious GI’s from the 75th Infantry Division inspect an abandoned Waffen-SS Kubelwagen. (US Army Signal Corps).

In the early morning hours of Christmas Day at about 03.00, a column of eight tanks from the 2nd SS preceded by an enemy crewed Sherman passed west through Grandmenil in the direction of Erezée.

Continue west of Grandmenil (following signs to Erezee N807) and pause on a series of uphill bends about 3.3 kilometres west of the village. This spot is locally known as Troup du Loup.

By this stage in the battle, the Americans were moving in more reinforcements in the shape of the 75th Infantry Division. Upon reaching Troup du Loup, troops of the 3rd Battalion, 289th Infantry attempted to set up positions blocking the road to Erezée and came under attack by this German column. The attacking armour wrought havoc among the infantrymen to either side of the road as the lead Panther ran over and destroyed several American vehicles and trailers. Several GIs fired bazooka rockets at the enemy tanks but none detonated since in their haste, the inexperienced soldiers had forgotten to remove the safety pins permitting them to arm the projectiles. Corporal Richard F. Wiegand seized the initiative, getting behind the lead tank and succeeding in destroying its engine before being killed by an enemy shell. The second Panther in line then tried to push the wrecked vehicle off the road but proved unable to do so. The wrecked tank remained in position effectively blocking the road whereupon the others pulled back in the direction of Grandmenil.

Following the engagement at Trop du Loup. It took some time for the US 3rd Battalion, 289th Infantry to reorganise, but by 08.00 the battalion set off on its assigned task of clearing the woods southwest of Grandmenil. At the same time the rest of the regiment, on the right, moved into an attack to push the outposts of the 560th Volksgrenadier Division back from the Aisne River. Brigadier General Doyle A. Hickey, the CCA, 3rd Armored commander, however, needed more help than a green infantry regiment could give if the 3rd Armored was to halt 2nd SS Das Reich and restore the position at Grandmenil. General Rose carried his plea for assistance up the echelons of command, and finally CCB of 3rd Armored was released from attachment to the 30th Infantry Division in the La Gleize sector to give the needed armoured punch.

Early that afternoon, Task Force McGeorge (a company each of armoured infantry and Sherman tanks) arrived west of Grandmenil. The task force was moving into the attack when disaster struck. Eleven P-38s of the 430th Fighter Squadron, which were being vectored onto their target by 7th Armored Division, mistook McGeorge’s troops for Germans and made a bombing run over the wooded assembly area killing three officers and thirty-six men in the process. The communications failure between the 3rd and 7th Armored Divisions had cost dear. Task Force McGeorge mounted a fresh attack at 20.00; McGeorge’s armoured infantry and a company from the 289th preceding the American tanks in the dark. Within an hour, five tanks and a small detachment of infantry in halftracks were in Grandmenil, but the enemy promptly counterattacked and restored his hold on the village.

The 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer Division had nevertheless failed on 25 December to enlarge the turning radius it so badly needed around the Grandmenil pivot. The German records show clearly what had stopped the advance. Every time that the 3rd SS Deutschland Panzergrenadier Regiment formed an assault detachment to break out of the woods south and west of Grandmenil, American artillery observers located on the high ground to the north, brought salvo after salvo crashing down. All movement along the roads seemed to be the signal for the much-feared Allied fighter-bombers to swoop down for the kill. To make matters worse, the 9th SS Hohenstaufen Panzer Division had failed to close up on the 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer’s right. Gruppenführer Lammerding dared not swing his entire division into the drive westward and thus leave an open flank facing the American armour known to be in the woods north of Manhay.

On the morning of 26 December the 4th SS Der Führer Panzergrenadier Regiment attacked northward using Manhay and the forest to the east as a line of departure. The 3rd SS Deutschland Panzergrenadier Regiment would have to make the main effort, forcing its way out of Grandmenil to the west in the direction of Erezée.

The German attempt to shake loose and break into the clear proved abortive. On the right, the 4th SS Der Führer Panzergrenadier Regiment sent a battalion from the woods east of Manhay into an early morning attack that collided with the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division and the Americans drove them off. By daylight, the enemy assault force was in full retreat, back to the woods. Plans for a second attack north of Manhay came to nothing since by then, the Americans held the initiative.

At the same time, the Germans tried to move west of Grandmenil, they also tried attacking to the northwest in the direction of Mormont, hoping to flank Erezée. The westward move began at false dawn, by chance coinciding with Task Force McGeorge renewal of its attack to enter Grandmenil. The road limited the action to a head-on tank duel. McGeorge’s Shermans proved no match for the Panthers which out-gunned them. When the shooting died down, the American detachment had only two medium tanks left in operational condition.

Sometime after this skirmish, one of the American tanks, that had reached Grandmenil during an attack the previous evening, suddenly came alive and roared out to join the task force. Captain John W. Jordan of the 1st Battalion, 33rd Armored Regiment, had led five tanks into the village, but during the earlier fight four had been hit or abandoned by their crews. Jordan and his crew sat through the night in the midst of the dead tanks, unmolested by the enemy. When Captain Jordan reported to his headquarters, he told of seeing a column of at least twelve Panthers, rumbling out of Grandmenil in a northerly direction. The 3rd Armored put up a liaison plane to locate the enemy armour but to no avail. Company L of the 289th Infantry knocked out the lead Panther in this group as the column passed through a narrow gorge on the road to Mormont and suffered numerous casualties as bazooka teams and tanks fought it out. German reports stated that this road was blocked by fallen timber and that intense American artillery fire blocked all movement north of Grandmenil. Whatever the reason, this group of tanks made no further effort to force the Mormont road.

Task Force McGeorge received sixteen additional Shermans at noon and a couple of hours later on the heels of three-battalion artillery shoot, burst through to retake Grandmenil. The pounding meted out by the 3rd Armored gunners apparently drove most of the panzergrenadiers in flight from the village and by dark, the 3rd Battalion, 289th Infantry had occupied half the village and held the road to Manhay.

Continue west on N807 and as you enter Briscol pause by the small church on the left in order to see the Belgian Touring Club stone marker indicating this high point in the German offensive. Continue west and turn left following the sign for Sadzot. Drive up into Sadzot swinging right at the top of the village. Here stands a monument to the 3rd Armored Division; 75th Infantry Division; 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion; the 289th Infantry Regiment and Company B of the 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion.

As 1944 came to a close, the Sixth Panzer Army made one last effort to breach the American defenses between the Salm and Ourthe Rivers. This small village was the epicentre of that stage in the battle. It was an action fought at squad and platoon level and later nicknamed ‘The Sad Sack Affair’ by the Americans who fought there.

Having failed in its attempts to break through at Manhay and Grandmenil, the 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer Division began to parcel out its troops. Some were left to cover the deployment of the 9th SS Hohenstaufen Panzer Division as it extended its position in front of the 82nd Airborne Division to take over the one time 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer Division sector. Other units shifted west to join the incoming remnants of the 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division, by then a shadow of its former self after suffering tremendous losses in the battle for the ‘Twin Villages’ of Krinkelt-Rocherath. The plan was to cross the Trois Ponts – Hotton road in the vicinity of Erezée and regain momentum for the drive to the northwest. The forces actually available were considerably less than planned. Traffic jams, a series of fuel failures and Allied air attacks had combined to slow down the movement of the 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division and just as the division was nearing the Aisne River, German Command OB West had seized the rearward columns for use around Bastogne. By the 27 December, the date set by 6th Panzer Army for the new attack, all 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division could muster was its 25th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, most of which was already in the line facing 3rd Armored Division. The 2nd SS Das Reich Panzer contribution to the attack force was limited to Sturmbannführer Ernst Krag’s Kampfgruppe Krag consisting of the reinforced divisional reconnaissance battalion, a battalion of selfpropelled guns and two rifle companies. The attack was scheduled to begin at midnight. During 27 December the lines of General Hickey’s CCA 3rd Armored Division had been redressed. In the process, the 1st Battalion of the 289th Infantry had tied in with Task Force Orr of the 3rd Armored on the Aisne River while the 2nd Battalion continued the 3rd Armored line through the woods southwest of Grandmenil. Unknown at the time, a one thousand-yard gap had developed south of Sadzot and Briscol between these two battalions. At zero hour, the German assault started forward through the deep woods; the night was dark, the ground pathless, steep and broken. The grenadiers made good progress, but the radio failed in the thick woods and it would appear that some of the attackers became disorientated. At least two companies of the 25th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment did manage to find their way through the gap between the battalions of the 289th and followed the creek into Sadzot, where they struck about two hours after the jump-off.

SS-Sturmbannführer Ernst Krag.

The course of the battle as it developed in the early morning hours of 28 December is extremely confused. The first report of the German presence in Sadzot was relayed to higher headquarters at 02.00 by artillery observers belonging to the 54th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, whose howitzers were positioned north of the village. The two American rifle battalions, when queried, reported no sign of the enemy. Inside Sadzot were bivouacked Company C of the 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion and a tank destroyer platoon; these troops rapidly recovered from their surprise and during the melée established a firm hold on the north side of the village. General Hickey immediately alerted the US 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion near Erezée to make an envelopment of Sadzot from west and east, but no sooner had the paratroopers deployed than they ran into Kampfgruppe Krag.

This engagement in the darkness seems to have been a catch-as-catch-can affair. The American radios, like the German radios, failed to function in this terrain (the 3rd Armored communications throughout the battle were mostly by wire and runner). Confusion caused the Germans to put mortar fire on their own neighbouring platoons. Squads and platoons on both sides carried on the fight firing at whatever moved. At daylight, the paratroopers got artillery support, which far outweighed the single battalion behind the enemy assault force, and moved forward. By 11.00, the 509th had clicked the trap shut on the Germans inside Sadzot.

There remained the task of closing the gap between the two battalions of the US 289th. At dark on 28 December, General Hickey put in the 2nd Battalion of the 112th Infantry, but this outfit, hastily summoned out for the fight, lost its direction and failed to seal the gap. Early on the morning of the following day, Hickey, believing that the 112th had made the line of departure secure, sent the 509th and six light tanks to attack toward the southeast. In the meantime, the Germans had reorganised, put in what was probably a fresh battalion and begun a new march on Sadzot. In the collision that followed, a section of German 75mm anti-tank guns destroyed three of the light tanks and the paratroopers fell back, but so did the enemy.

Germans who died when the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment fought the 1st and 2nd Battalions of SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 25 of the 12th SS Panzer Division at Sadzot. (US Army Signal Corps).

During the morning, the 2nd Battalion, US 112th Infantry, got its bearings – or so it was believed – and set out to push a bar across the corridor from the west. Across the deep ravines and rugged hills American troops were sighted, and believing them to be the 2nd Battalion, the troops of the 112th veered toward them. What had been seen, however, proved to be the paratroopers of the 509th. After this misadventure, and the jolt suffered by the paratroopers, Hickey and the battalion commanders concerned, worked out a co-ordinated attack. First, the paratroopers put in a twilight assault, which forced the Germans back. Then, the 2nd Battalion 112th made a night attack with guiding this time on 60mm illuminating mortar rounds fired by the 2nd Battalion of the 289th. Crossing through deep ravines, the infantrymen of the 112th drove the enemy from their path. At dawn on the 29th, the gap was finally closed.

The German failure to penetrate through the Erezée sector on 28-29 December, was the last serious bid by the Sixth Panzer Army in an offensive role. On that day, Generalfeldmarschall Model ordered 6th Panzer Army to go over to the defensive and began stripping it of its armour. The German commanders left facing the VII and XVIII Airborne Corps east of the Ourthe River, record a number of attacks being made between 29 December and 2 January. The units involved included infantry detachments from the 9th SS as well as the 18th and 62nd Volksgrenadier Divisions. Ordering these weak and tired units into the attack when the German foot soldier knew that the great offensive was ended, was one thing. To press the assault itself, was quite another. The American divisions in this sector note only at the turn of the year ‘Front quiet’, or ‘Routine patrolling’. The initiative had clearly passed to the Americans.

Return to the main road (N807) turning left (west) in the direction of Erezée. Drive through Erezée and continue west on N807 passing through Fisenne and Soy. West of Soy on N807, watch out for the crossroads named in honor of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment to the northwest corner of which is a monument to the 517th. Pause here.

In May 1992, a group of veterans of the 1st Battalion, 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment returned to Belgium for the dedication of this monument. The 1st Battalion incurred 139 casualties with fourteen men killed in action during its fighting in the Soy-Hotton-Lamormenil area from 23-26 December 1944. Artillery and tank fire reduced this crossroads (locally known as ‘Quatre Bras’) to a scene of utter desolation. The stench of cordite, charred flesh and white phosphorous hung in the air for days after the capture of the crossroads area. A lone pine tree survived the rigors of battle only to be cut down some forty-seven years later by foresters unaware of its place in history.

After pausing at the 517th monument turn left at this same junction off N807 and at the downhill bends pause by the stone monument on the left.

As a young boy, Florent Lambert lived through the battles in this area and never forgot the debt he and his countrymen owed their allied liberators. On 3 January 1945, Captain James M. Burt of Company H, 3rd Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division, was leading a column of medium tanks down this hill in the direction of Melines. Driving these vehicles on this icy slope proved tricky and as Captain Burt neared the bottom of the hill he heard a violent explosion to his rear. Just across the valley, a group of civilians preparing to leave the area also heard the explosion and turned to see thick smoke rising above the trees. As the tank column jarred to a halt, men ran in both directions to find out what had happened. Some infantrymen of the 84th Infantry Division had been riding ‘piggy-back’ aboard one or more of the long-barrelled Shermans. The tank, commanded by Lieutenant George C. Connealy, had been inching its way down the road when it skidded on the hard-packed ice and snow off the edge of the winding road. Upon doing so, it struck a daisy chain of mines that detonated simultaneously blowing the tank turret clear across the road, killing Lieutenant Connealy, his crew and the hitch-hiking GIs. Florent Lambert never forgot those young men who gave their lives that cold winter’s day, and in their honor he built this monument.

Continue downhill keeping to the right at the bottom and past the road to Beffe (signposted Werpin). As you then drive uphill, on the right is another monument erected on the initiative of Florent Lambert.

This monument commemorates several American units, which served in this area at various points throughout the battle. The units include 3rd Armored Division, 75th Infantry Division, 2nd Armored Division and the 84th Infantry Division. It also features a portrait of Corporal John Shields of Company C, 23rd Armored Infantry Battalion, 7th Armored Division whose remains were discovered about fifty yards further up the road in the ditch on the right hand side by Florent Lambert’s father in 1947.

Continue up the road keeping an eye out for a small stone cross on the right, which shows where Mr. Lambert Sr. discovered Corporal Shields remains. Continue straight ahead in the direction of Werpin. As the road begins to level off, the wooded hill to the left is known as ‘La Roumière’. Pause with the high wooded ground off to your left.

The arrival of the US 75th Infantry Division in the European Theatre, more specifically, in the 3rd Armored Division sector, promised the needed rifle strength to establish a solid defense in the rugged country east of Hotton and along the bluffs of the Aisne River. To establish a homogenous line the Americans would have to seize the high, wooded and difficult ground south of the Soy-Hotton road (N807), and at the same time, push forward to close up to the banks of the Aisne River over the tortuous terrain south of the Erezée-Grandmenil road. With two regiments of the 75th attached to the 3rd Armored (the 289th and 290th Infantry Regiments), General Rose ordered a drive to cement the CCA wing in the west.

The units of the 75th had been scattered in widely separated areas after their arrival in Belgium. A smooth-running supply system had not yet been set up, and to concentrate and supply the rifle battalions would prove difficult. Colonel Carl F. Duffner’s 290th Infantry received orders at 16.00 on the 24 December to assemble at Ny for an attack to begin two hours later. There ensued much confusion, with orders and counter-orders, and finally the attack was re-scheduled for 23.30. The regiment had no idea of the ground over which it was to fight but did know that the line of departure was then held by a battalion or less of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment deployed along the N807 between Soy and Hotton. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions were chosen for this first battle, their objective La Roumière.

About midnight on the 24 December the battalions started their assault companies forward, little did they know it but the men of the 3rd Battalion were embarking upon a nightmare mission. Second Lieutenant Paul B. Ellis Jr. commanded the 2nd Platoon of Company K that fateful Christmas Eve as they reached the crest of La Roumière. In a letter to the author dated 8 October 1991, he recalled the attack on the hill:

‘As my platoon moved from right to left along the crest of the hill, we spotted a machine-gun nest with four Germans in it. They were firing down the hill and I don’t think they saw us. Cyril Gerwitz and I tossed two grenades in the emplacement and either killed or knocked out all four Germans. A man from my platoon went in and made sure the war was over for all four Germans. Private First Class Gerwitz was my runner. Each officer had a runner who was known by the company commander, to relay messages. When my platoon ran out of ammunition on top of the hill, I ordered Cyril to leave. I still had a few rounds in my carbine to cover him and the others. He would not go. When I ran out of “ammo”, we took off down the hill and a little German in a greatcoat that reached his ankles came after us firing a “burp-gun” (machine pistol) as he ran 75 to 100 yards behind us. We had almost reached the ditch beside the road when he fired a long burst that killed Gerwitz and wounded me.’

Lieutenant Ellis’ platoon sergeant, ‘Woody’ Woodrome killed the pursuing German who’d followed Ellis to the edge of the road. Losses in this débacle were severe with most of the officers either killed or wounded. On the afternoon of Christmas Day, more infantry arrived (probably from the 517th Parachute Infantry), plus a platoon of tank destroyers, and a fresh assault was organised. This carried through the woods and onto the crest of the slope. The 290th Infantry Regiment had undergone their ‘Baptism of Fire’.

Continue through Werpin bearing right at the church and proceed to Hampteau. Here, turn right on N833 towards Hotton and in the centre of town pause in the vicinity of the Ourthe River Bridge, which is off to your right side.

PFC Cyril J. Gerwitz the runner for 2nd Platoon, Company K, saved the life of Lieutenant Ellis when he gave his own. (Author’s collection, courtesy Paul and Rosemary Ellis).

Just north of the bridge note the Hotel de L’Ourthe that from 20 December served as the forward command post of General Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division.

On the southeast end of the bridge note the plaque to Lieutenant Colonel Harvey Fraser’s 51st Engineer Combat Battalion.

The town of Hotton is built astride the main channel of the Ourthe River at a point where the valley widens. Here, a series of roads converge to cross the river and proceed on the West Bank to the more important junction centre at Marche from which roads radiate in all directions. Here in 1944, a Class 70 two-way wooden bridge spanned the river. In the buildings on the East Side about two hundred men from the service detachments of the ‘Spearhead’ 3rd Armored Division and its Combat Command Reserve prepared to defend the town. In addition, one light and one medium tank were positioned on the east bank. Across the river the following units defended the western end of the bridge. The 1st Platoon of Company A, 51st Engineer Combat Battalion; a squad from Company B of the 51st; a squad of engineers from 3rd Armored Division with a 37mm anti-tank gun; two 40mm Bofors Anti-aircraft guns; several bazooka teams; and some 50 calibre machine guns. An additional engineer squad from the 51st guarded a footbridge at Hampteau, two thousand yards south of Hotton.

Second Lieutenant Paul B. Ellis commander of The 2nd Platoon, Company K of the 290th Infantry Regiment in the action at La Roumière. (Author’s collection, courtesy Paul and Rosemary Ellis).

At about 07.00 on 21 December 1944, twenty-five German infantrymen crossed the Ourthe River at Hampteau in an initial probe of the Hotton defenses by the 116th Windhund (Greyhound) Panzer Division. About half an hour later, mortar and small arms fire heralded the opening attack against the bridge defenders. Despite casualties and confusion Major Jack W. Fickessen, executive officer of the 23rd Armored Engineer Battalion hastily set up the defense of the bridge. His men drove engineer trucks out to block the roads then distributed bazookas and machine guns for a close-in defense of the town. Taking advantage of the woods that came right up to the eastern edge of Hotton, four or five enemy tanks rumbled forward to lead the assault. The Germans immediately knocked out both American tanks on the east side of the river but on the opposite bank, an American tank destroyer suddenly appeared and knocked out one of the attacking Panther tanks. Although the German infantry managed to gain control of about half the buildings on the east bank, the Americans defending the remainder and those on the other bank prevented the enemy from reaching the bridge.

Anti-tank gunners of the 84th Infantry Division see to the maintenance of their 57mm anti-tank gun. (US Army Signal Corps).

At his command post in Marche, Lieutenant Colonel Harvey ‘Scrappy’ Fraser, commander of the 51st Engineers remained in constant telephone contact with his men on the spot who gave him a running commentary on the fighting in progress. As the situation began to deteriorate, Fraser called General Bolling of the 84th Infantry Division to request support. General Bolling refused this request indicating that he couldn’t accept as factual, reports from ‘on the spot’ eye-witnesses.

At 08.53 the telephone line between Fraser and his men in Hotton went out so he and his driver drove to Hotton to join the defenders at the bridge. In the course of the morning, the defenders knocked out some four enemy tanks. Private Lee J. Ishmael, Fraser’s driver knocked out one such tank while manning a 37mm anti-tank gun when its crew proved reluctant to do so.

Later that afternoon, the Germans managed to damage the wiring leading to the demolition charges on the bridge. Under enemy small arms fire, Lieutenants Floyd D. Wright and Bruce W. Jamison of the 51st Engineers waded through chest deep, ice cold water and succeeded in repairing the wiring. The engineers had the situation well in hand by the time reinforcements from the 334th Infantry of the 84th Division arrived.

Turn west (left) on N86. As you climb up out of town take the left turning marked Menil where you see a sign for the British and Commonwealth War Cemetery (Hotton War Cemetery). Continue on this road until you reach the cemetery on your right.

Here lie buried 667 British and Commonwealth war dead including casualties from the ‘Battle of the Bulge’. Although in Allied terms essentially an American battle, elements of the British XXX Corps and 6th Airborne Division deployed and fought in the area. At La Roche, a fine marble plaque and other monuments commemorate the role of British units in the battle. About fifteen miles southwest of Hotton, in an attack against the Germans defending the village of Bure, the 13th Battalion of the Parachute Regiment suffered some 189 casualties. Sixty-eight lie buried in this cemetery. Theirs was indeed a valiant story. For those wishing to make a side trip to Bure, a memorial to the 13th Battalion stands outside the village church while inside a Roll of Honor lists the men of the battalion and the Belgian Special Air Service killed in the vicinity of the village.

Return to N86 turning west (left) in the direction of Marche. In Bourdon, turn left in the direction of Verdenne/Marenne. Cross the railroad and climb the hill to your front, keeping to the same road, Pass the local soccer pitch to your right and keep right, passing the monument to the Verdenne Pocket. Continue towards the outskirts of Verdenne passing the grounds of the Château de Verdenne (private property) to your left and stop at the entrance to the village.

On the night of 23 December, two companies (dismounted troops of the 116th Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion) infiltrated the American lines at the junction point between the 334th and 335th Infantry Regiments. They stealthily worked their way forward and by dawn were to the rear of the 334th. There they sought cover on the wooded ridge north of Verdenne. This village, outposted by the Americans, was the immediate goal of the German attack planned for 24 December. Commanding the Marche-Hampteau road – roughly the line held by the left wing of the 84th Division – it afforded immediate access via the good secondary route to Bourdon on the main Hotton-Marche highway (N86), and its possession would offer a springboard for the German armoured thrust.

A delay in fuel supply meant that the 116th Panzer did not attack at daylight on 24 December. Instead, the division commander, Generalmajor Siegfried von Waldenburg, sent detachments of his 60th Regiment into the Bois de Chardogne, the western extrusion of a large forested area partially held by the Germans southwest of Verdenne. Unusual movement in the woods alerted the Americans to the enemy presence during the morning so General Bolling sent the 1st Battalion, 334th Infantry supported by three tank platoons of the 771st Tank Battalion to trap the infiltrators. The American tanks suddenly appeared on the wooded ridge north of Verdenne and ran head on into the enemy just assembling at the wood’s edge in assault formation. The Germans broke and fled, some fifty surrendered and the Americans cleared the woods.

About an hour after the above incident, five enemy tanks and two halftracks accompanied by a hundred or so grenadiers, struck Verdenne from the south and in the process, captured the village. They then pushed on to the château and that evening drove the wedge even deeper.

Companies I and K of the 334th Infantry fell back to a new line barely in front of the crucial Marche-Hotton road, and German light artillery moved up to bring the road under fire.

Return to the ‘Verdenne Pocket’ monument and stop.

General Bolling then ordered his reserve, the 333rd Infantry, to send its 3rd Battalion to re-take Verdenne. As they entered the woods in the pitch-black dark, the men of Company K ran into a column of seven or eight tanks. Sergeant Donald Phelps manning the point went forward to check the lead tank. As he pounded his fist on the side of the vehicle, the hatch opened slowly and a somewhat curious voice asked ‘Was ist los?’ Immediately a firefight broke out and under machine gun fire from the tanks the men of Company K sought cover in the roadside ditches. Sergeant Phelps and his buddies had run smack into a battalion-size force of forty tanks, armored infantry and supporting engineers and artillery of the 116th Panzer Division. Severely lacerated before they could break away, the remaining forty men of Company K joined the main assault against Verdenne an hour later.

Intense American artillery fire softened up the Germans in Verdenne and the attacking GIs succeded in getting clear through the village – although fighting resumed at daylight with the dangerous task of house-clearing. Some 289 German soldiers surrendered by the end of Christmas Day.

The seizure of Verdenne cast a loop around the German tanks and infantry in the woods north of the village. At noon on Christmas Day a tank company of the 16th Panzer Regiment tried an assault in staggered formation against Verdenne but found Company B of the 771st Tank Battalion waiting for them and lost nine tanks – its entire complement.

Von Waldenburg still hoped that the detachment in the woods could be saved, for during the day Oberst Otto Remer’s Führer Escort Brigade came in on his right, freeing the troops he had deployed to watch Hampteau and the Hotton approaches. More than this, he apparently expected to use the wedge which would be created in reaching the pocket as a means of splitting the Marche-Hotton line and starting a major advance westward.

Tankers attached to 84th Infantry Division on the look out for enemy activity. An abandoned German “Kubelwagen” stands snow covered behind them. (US Army Signal Corps).

The area in which the Germans were hemmed posed a very neat problem in minor tactics. It was about 800 yards by 300, densely wooded and shaped with an inner declivity somewhat like a serving platter. Guns beyond the rim could not bring fire to bear on the tanks inside, and tanks rolling down into the pocket would be in the same position if they moved up and over the edge. Assault by infantry could be met by tank fire whether the assault went into or came out of the pocket.

Companies A and B of the 333rd Infantry tried such an assault in a pre-dawn attack on 26 December. The American skirmish line, its movements given away by the snow crackling underfoot, took a number of casualties and was beaten back, but it gave some test of the enemy strength, now estimated to be two rifle companies and five tanks. Actually, most of the Germans in the 1st Battalion, 60th Panzergrenadier Regiment, took part in the fighting at the pocket or in attempted infiltration through the woods to join their comrades there. One such relief party, led by a tank platoon, did cut its way in on the morning of the 26 December. Now that the enemy had been reinforced, the 333rd infantry decided to try the artillery, although not before the regimental commander had been assured that the gunners would fire with such minute accuracy as to miss the friendly infantry edging the pocket. Throughout the rest of the day, an 8-inch howitzer battalion and a battalion of 155mm guns hammered the target area intent on jarring the panzers loose, while a chemical mortar company tried to burn them out.

On 27 December, patrols edged their way into the pocket to find nothing but abandoned tanks. The previous evening, von Waldenburg learned that the Führer Escort Brigade was being taken away from his right flank and that he must go over to the defensive at once. Still in radio contact with his troops in the pocket, he ordered them to come out, synchronising their move with an attack toward Menil at dusk. Perhaps the feint at Menil served its purpose – in any event, most of the grenadiers made good their escape, riding out on the tanks still capable of movement.

Return to N86 turning left in the direction of Marche. Just before reaching the town cemetery in Marche, note the red brick house on the left side of the road. For the fiftieth anniversary of the battle, the owner painted a large ‘Rail-splitter’ patch on the eastern gable end in honor of the 84th Infantry Division. From here head to the ‘Musee de la Farenne’ at 22 Rue du Commerce. On the wall in the courtyard of this building are plaques commemorating the 84th Division and its commander, Brigadier General Alexander R. Bolling.

Some fifty years after the battle Mr and Mrs Fautré-Blétry show their continued appreciation for the ‘Railsplitters’ by painting the 84th Division patch on their gable end. (Author’s collection).

On 19 December, US General Bolling received orders to make ready for relief by the 102nd Infantry Division, and by noon the next day, his leading regimental combat team, the 334th, was on the road from the Roer River front to Belgium. First Army ordered General Bolling to assemble the 84th in the sector of Marche.

He set up his command post in Marche late on the afternoon of 21 December. The only friendly troops he found in the neighbourhood were those of Lieutenant Colonel Harvey ‘Scrappy’ Fraser’s 51st Engineer Combat Battalion, whose command post was also in Marche. This battalion was part of a small engineer force, which VII Corps had gathered to construct the barrier line along the Ourthe River. Colonel Fraser spread out his two companies at roadblocks and demolition sites all the way from Hotton, on the river, to a point just south of the Champlon crossroads on the Bastogne-Marche highway (N4).

The first word of an attacking enemy reached the 84th Division command post in Marche at 09.00 on 21 December, but the attack was being made at Hotton, to the Northeast, where the 116th Panzer division had earlier started its assault against the Ourthe River Bridge. General Bolling ordered his single regimental combat team, the 334th under Lieutenant Colonel Charles E. Foy, to establish a perimeter defense around Marche. Meanwhile Colonel Fraser had asked for help in the fight at Hotton, but by the time troops of the 334th reached the scene in mid-afternoon, the embattled engineers and soldiers of 3rd Armored Division had halted the enemy in their tracks and saved the bridge. General Bolling received word from army headquarters that his division was to hold the Marche-Hotton line. By midnight on the 21 December, he had his whole division and the 771st Tank Battalion assembled and in process of deploying on a line of defense. About dark, as the second team detrucked, Bolling relieved the 334th of its close-in defense of Marche and moved the 2nd and 3rd Battalions out to form the left flank of the division, this anchored at Hotton where troops of the 3rd Armored Division had finally been met. The 335th Infantry, under Colonel Hugh C. Parker, deployed to the right of the 334th with its right flank on N4 and its line circling south and east through Jamodenne and Waha. Colonel Timothy Pedley’s 333rd Infantry, the last to arrive, assembled north of Marche in the villages of Baillonville and Moressée ready to act as cover for the open right flank of the division – and army, or as division reserve. During the night, the regiments pushed out a combat post line, digging in on the frozen ground some thousand metres forward of the main position, which extended from Hogne on highway N4 through Marloie and along the pine-crested ridges southwest of Hampteau. The division was now in position forward of the Marche-Hotton road (N86) and that vital link appeared secure. Earlier in the day, the 51st Engineer roadblocks on the Marche-Bastogne highway had held long enough to allow the 7th Armored Division trains to escape from Laroche and reach Marche. At 19.30 the tiny engineer detachments received orders to blow their demolition charges and fall back to Marche, leaving the road to Bastogne in German hands.

Continue on N836 in the direction of Rochefort via Jemelle. Stop in Rochefort town centre.

Anglo-American traffic on a street in Marche. (US Army Signal Corps).

On 24 December 1944, the hottest points of combat in this sector were Rochefort, Buissonville and the Bourdon sector east of the Marche-Hotton road (N86). A couple of hours after midnight, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr began their main attack against the defenders of Rochefort. The Americans held fast and made a battle of it in houses and behind garden walls. Companies I and K of the 333rd Infantry, 84th Division, concentrated in and around the Hotel du Centre, dug in a brace of 57mm anti-tank guns and a selection of heavy machine guns in front of the hotel, and so interdicted the town square. About 09.00 on Christmas Eve, the 3rd Battalion lost radio contact with division, but four hours later, one message did reach Rochefort: an order from General Bolling to withdraw. By this time, a tree burst had put the anti-tank guns out of action. To disengage from this house-to-house combat wouldn’t be easy. Fortunately, the attackers had their eyes firmly fixed on the town centre market place, apparently with the objective of seizing the crossroads there so that armoured vehicles could move through from one side of town to the other.

The Germans were so preoccupied that they neglected to bar all exits from Rochefort. Driven back into a small area around the battalion command post, where bullet and mortar fire made the streets an inferno, the surrounded garrison made ready for a break. Enough vehicles had escaped damage to mount the battalion headquarters and Company M. The rest of the force formed up for a march out on foot. At 18.00, the two groups made a concentrated dash from the town, firing wildly as they went and hurling smoke grenades, which masked them, momentarily, from a German tank lurking nearby. The vehicular column headed west for Givet without being ambushed. The foot elements headed north with the intention of reaching the outposts of a 3rd Armored Division task force known to be thereabouts, but the seemingly ubiquitous presence of enemy troops severely hampered movement. During the night, battalion sent some trucks east of Givet and located parts of Companies I and K. Patrols from the 2nd Armored Division picked up two officers and thirty-three men of Company I in an exhausted state and returned to the American lines. The defense of Rochefort had not been too costly: the defenders left behind fifteen wounded men in the care of a volunteer medic while the attackers captured or killed a further twenty-five. Generalleutnant Bayerlein, commander of the Panzer Lehr, who himself fought in both engagements, would later rate the American defense of Rochefort as comparable in courage and significance as that of Bastogne.

Take N911 in the direction of Ciergnon. West of Ciergnon turn right on N94 in the direction of Celles/Dinant. Once through Celles, pause at the junction with N910 and note the wrecked Panther in front of the café to your right.

In its attempt to cross the Meuse River, the 47th Panzer Korps’ 2nd Panzer Division’s reconnaissance element reached the village of Foy Notre Dame, between here and Dinant, at midnight on 23 December. In support of this spearhead, the 2nd Panzer Division commander, Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert sent Major Ernst von Cochenhausen’s Kampfgruppe forward. This battered hulk is what is left of Kampfgruppe von Cochenhausen’s lead tank after it struck a mine early on the morning of 24 December. Later, the village council moved it to its present location.

Continue north on N94 to Celles (signposted Dinant) crossing N910 and in Boisselles take a minor right under N97 following the sign for Foy Notre Dame. Upon entering the village after passing under the arch, turn left then at the church turn right. Just past the church, watch out for a Belgian Touring Club stone marker and a cross on your right.

Private Patrick E. Shea a BAR gunner with Company B, 329th Infantry Regiment of the 83rd Infantry Division. He and his company repulsed enemy attacks at Rochefort for two days 6/1/45. (US Army Signal Corps).

It was in and around this village that the 2nd Panzer Division spearhead was annihilated. Thanks to intelligence gathered by two local former Belgian army officers, Captain Jaques de Villenfagne de Sorrines and Lieutenant Philippe le Hardy de Beaulieu, British troops in nearby Sorrines learned of the proximity and precise location of German troops, vehicles and guns. On 24 December, American and British units supported by ground-strafing P-51s put pressure on the Germans in and around Foy Notre Dame, effectively wiping them out over the next couple of days. Major General Ernest N. Harmon’s US 2nd Armored Division was instrumental in this destruction of the 2nd Panzer Division. Von Lauchert’s men had achieved the deepest penetration in Hitler’s last desperate attempt to snatch victory in the West.

Return south and pass under the N97 turning right, then a little further, turn right again back under the N97 onto N94. Follow N94 west and downhill turning right toward Dinant at the Meuse River. Stop by the large triangular rock formation on the east bank known as the ‘Rocher Bayard’.

During the night of 23 December, three men of Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny’s 150th Panzer Brigade, driving a captured American jeep, reached the Rocher Bayard only to be stopped dead in their tracks by men of the British 29th Armoured Brigade. A stone positioned close to the north side of the rock marks this as the furthest point west reached by any German soldier in WACHT AM RHEIN.

Continue on into Dinant for a couple of well earned Belgian Trappist beers!

Suggested Reading:

MacDonald: Chapters 26,27 and 29.

Cole: Chapters 16,22 and 23.

Breuer: Bloody clash at Sadzot.

Fowle and Wright: The 51st Again. Chapters 5, 6 and 7.

Pallud: The Battle of the Bulge: Then and Now Parts 3 and 4.

Brigadier General W.B. Palmer VII Corps Artillery Commander. (US Army Photo, courtesy General Palmer).