Chapter 4

THE COMMON COLD

ONE OF the most vexing aspects of pediatrics is dealing with the common cold. Everyone gets it, everyone suffers from it, and everyone hates it, yet there is not much that modern medicine has to offer in terms of treatment.

The common cold leads to coughing, sneezing, runny nose, sore throat, congestion, and fever. There are countless drugstore medications and homemade remedies that people take to combat a cold. Unfortunately, little evidence supports their effectiveness. Most children will get 6–8 colds (or more) per year; thankfully, all of them will go away with time and require little intervention.

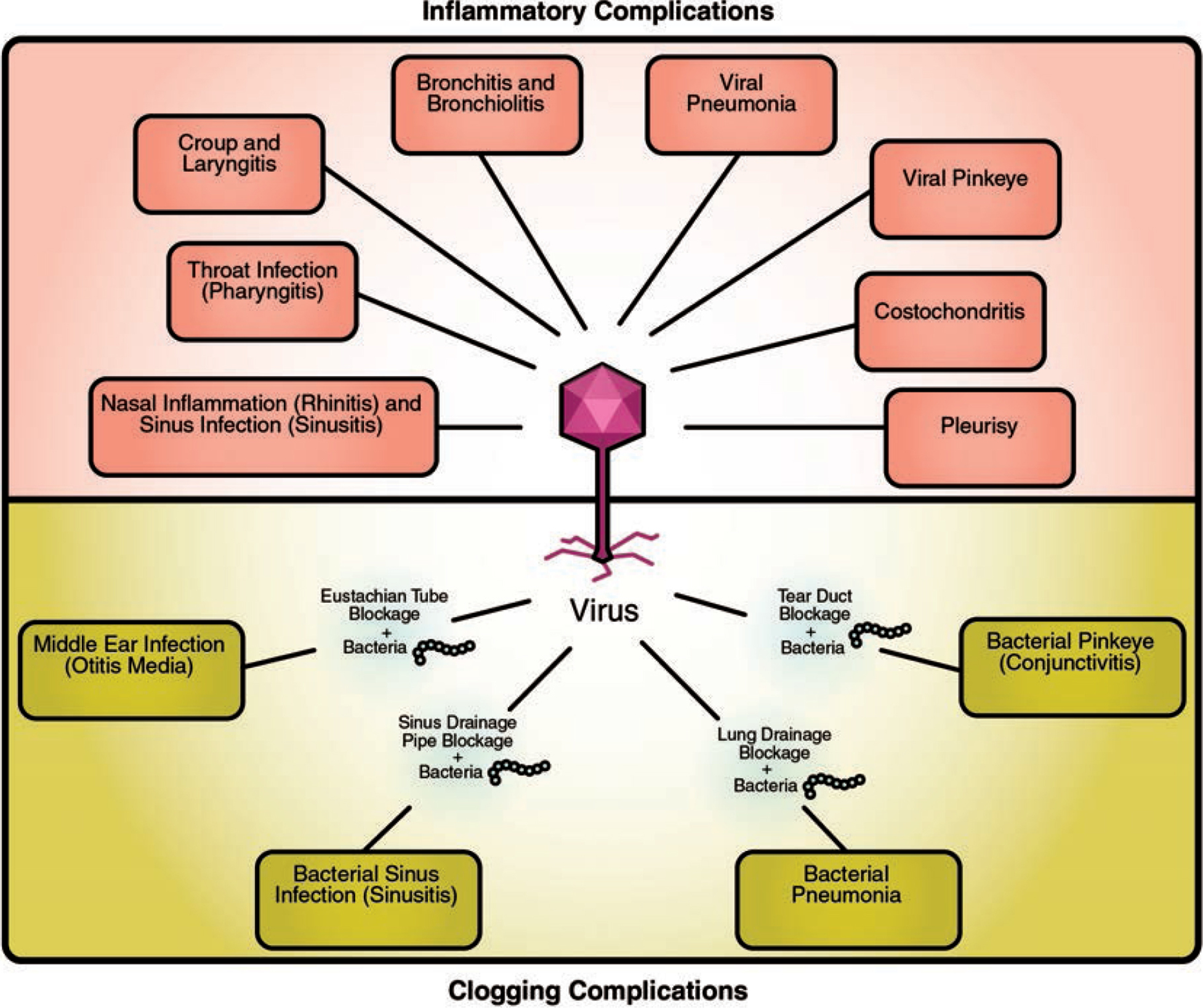

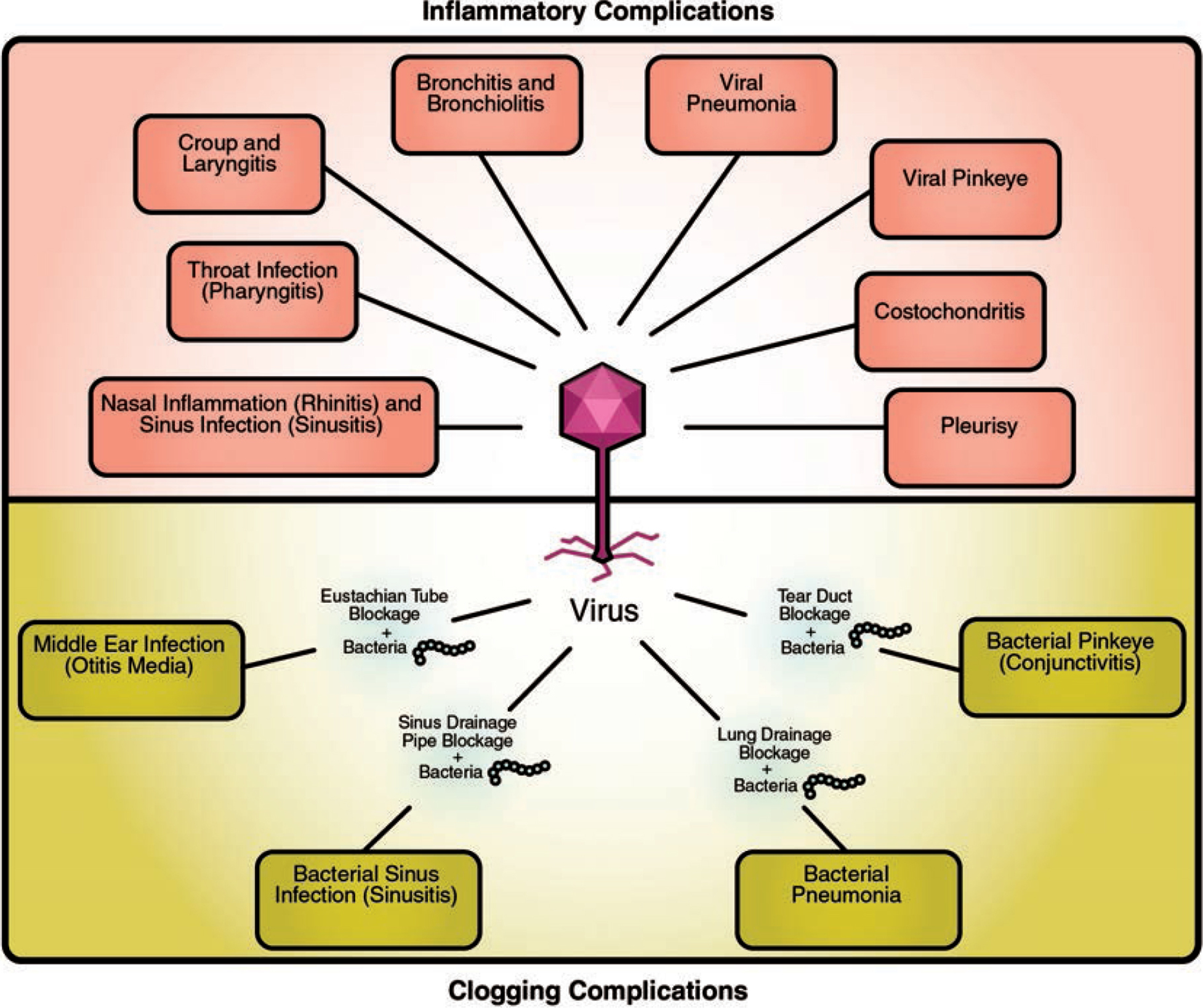

It is important to understand the common cold thoroughly, however, because it is a gateway infection that can lead to a host of other complications commonly seen in pediatrics. There are two categories into which all complications of the common cold fit: inflammatory complications and clogging complications.

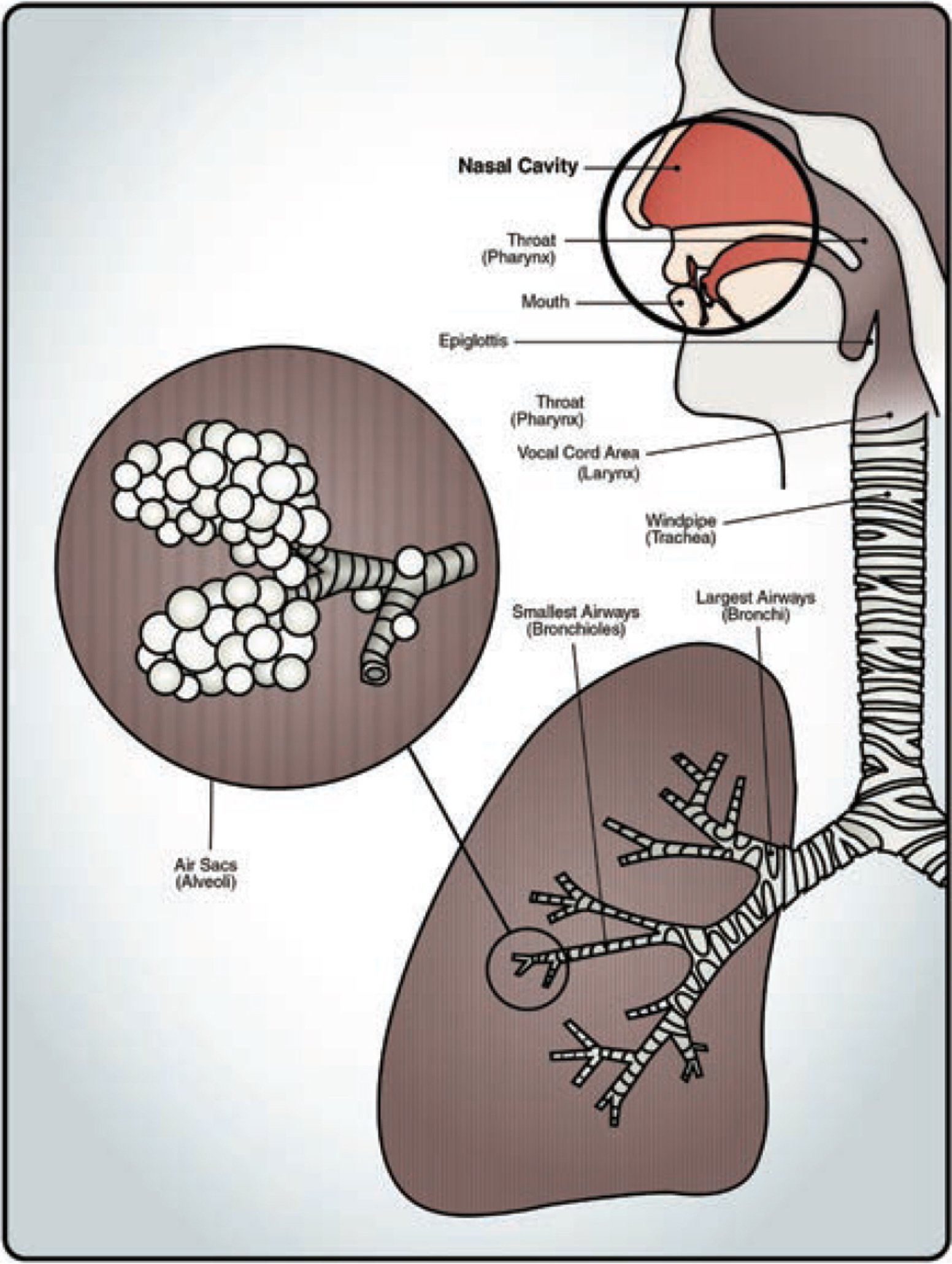

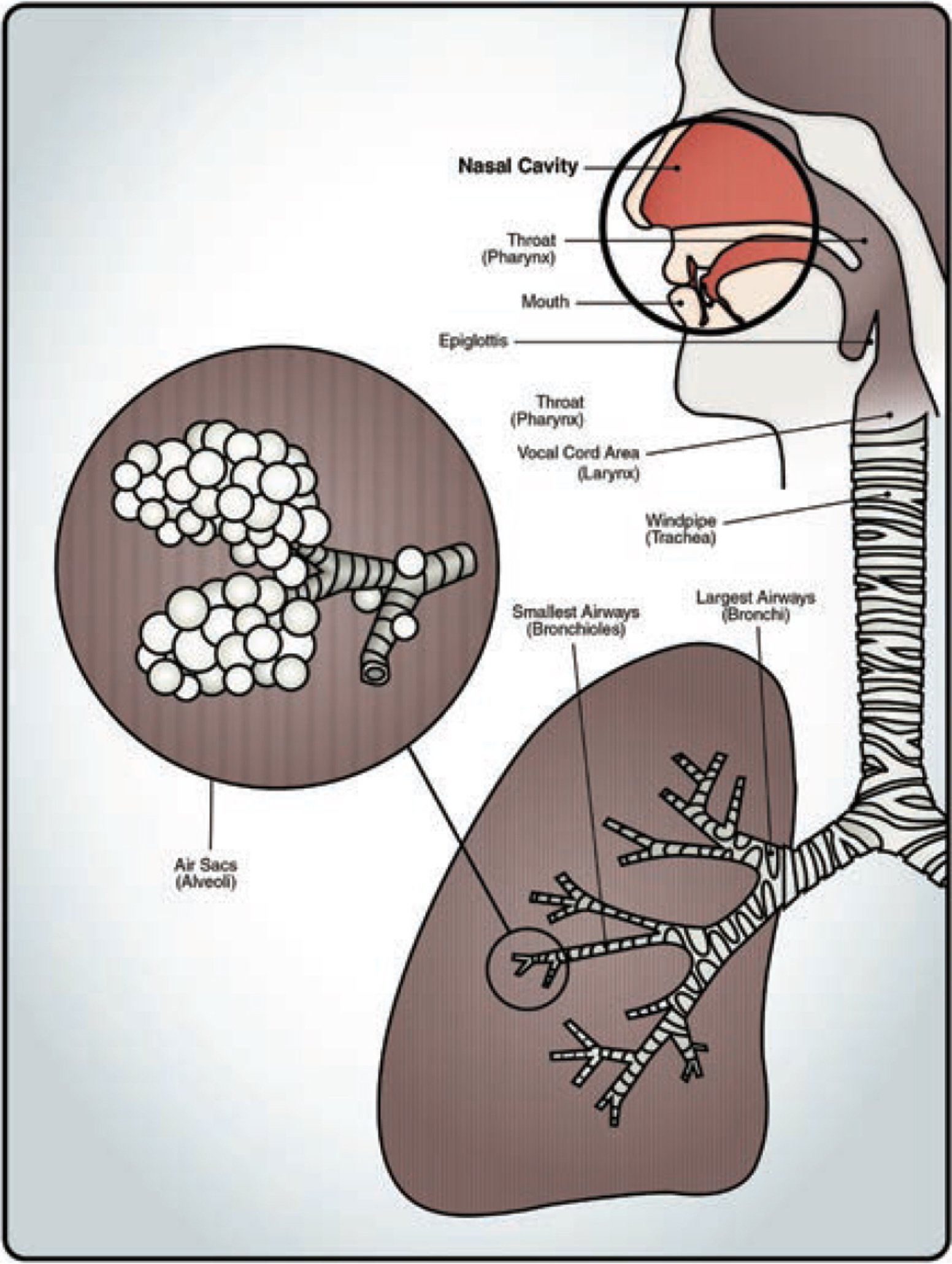

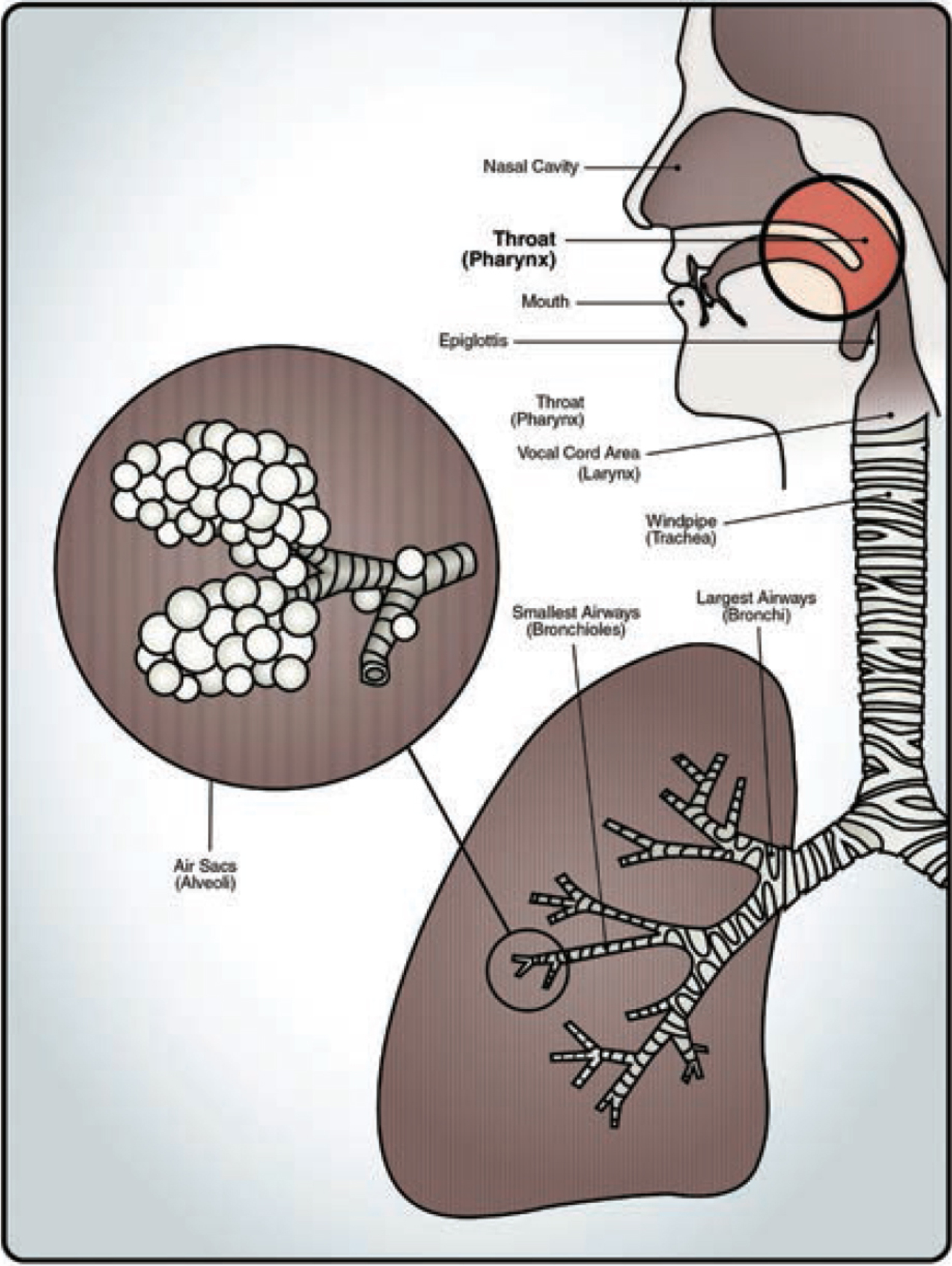

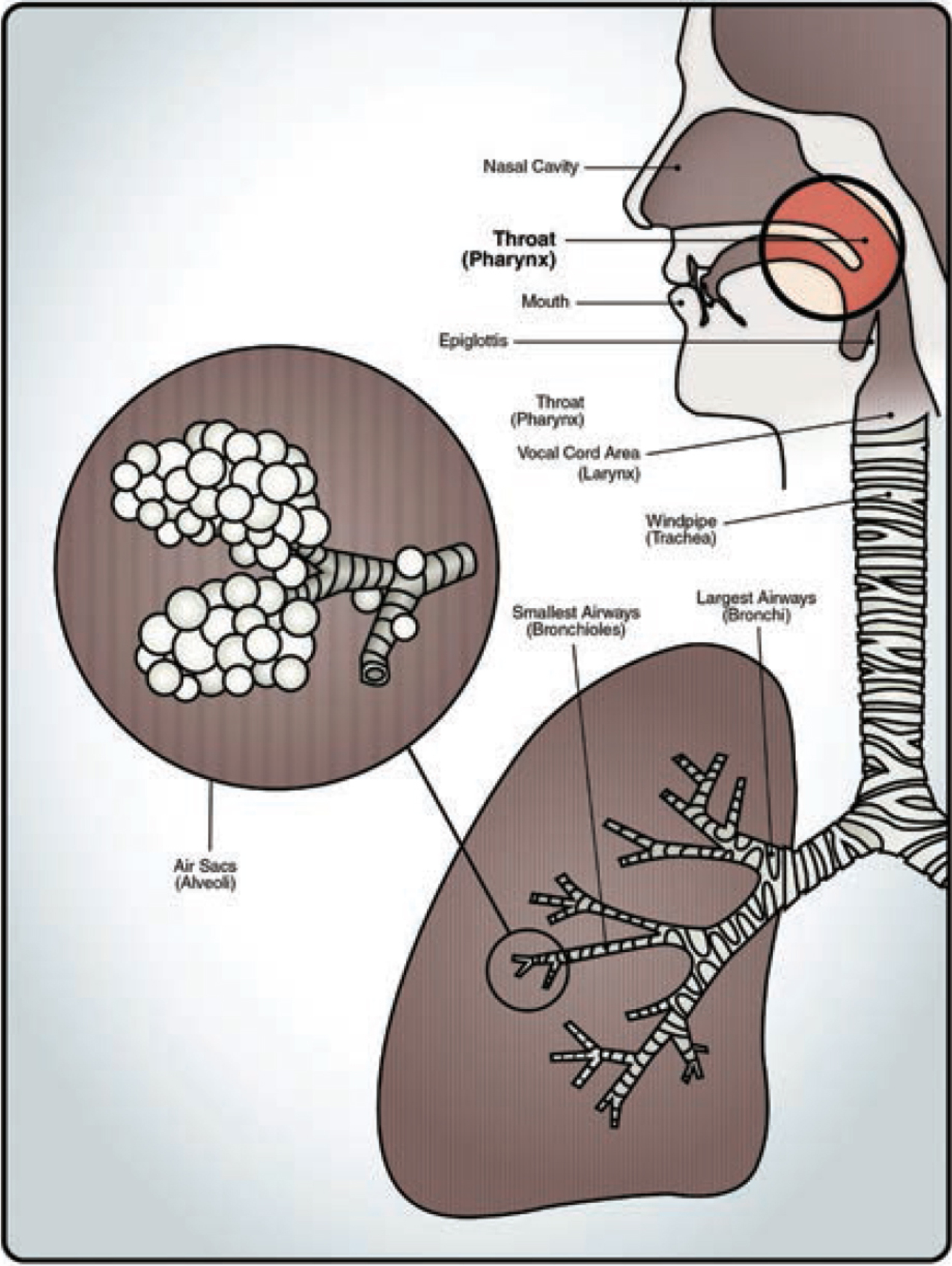

Inflammatory complications (see here) of the cold occur when the invading virus inflames any part of the respiratory tract, starting from the mouth all the way down to the alveoli (air sacs) of the lung. This can lead to nasal inflammation (rhinitis), a viral sinus infection, a viral throat infection, croup, laryngitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, a viral pneumonia, or a viral pinkeye (conjunctivitis). Although these complications cannot be cured by antibiotics, things can be done to help monitor, comfort, and sometimes treat the child.

Clogging complications (see Chapters 5 and 6) occur when colds create mucus and congestion. This can lead to blockage of various drainage pipes in the body, creating stagnant fluid and allowing bacteria to fester and multiply. This can lead to an ear infection, a bacterial sinus infection, a bacterial pneumonia, or a bacterial pinkeye. Clogging-induced infections are initially triggered by a viral cold, but subsequently will involve bacteria and thus often require antibiotics; whereas when dealing with just the common cold, which is caused by a virus, antibiotics are neither needed nor helpful.

Understanding how colds typically improve and go away on their own, or else evolve into complications, can help a parent distinguish when a child can stay at home and duke it out, versus when a child needs to be evaluated by a doctor for possible intervention.

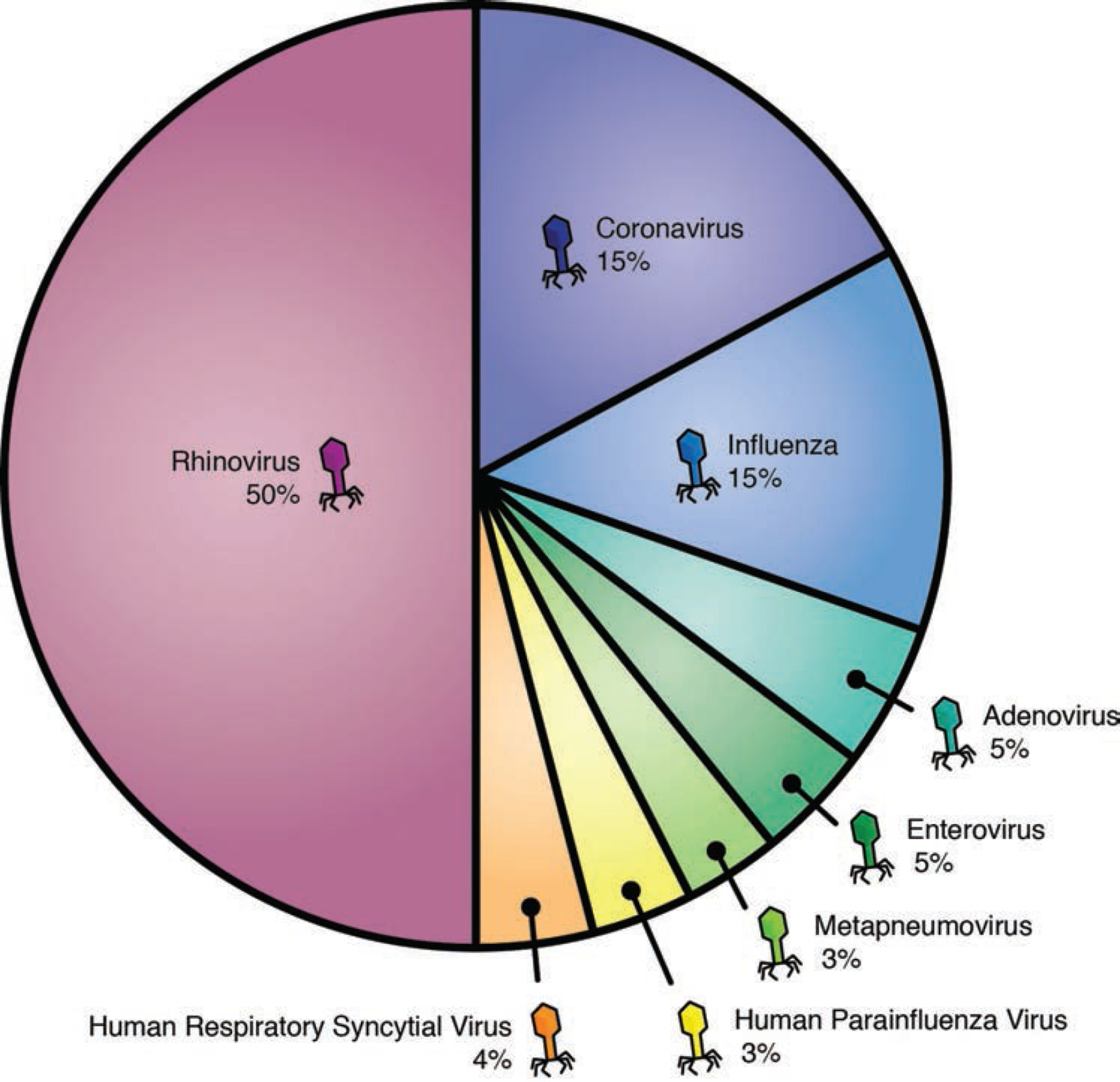

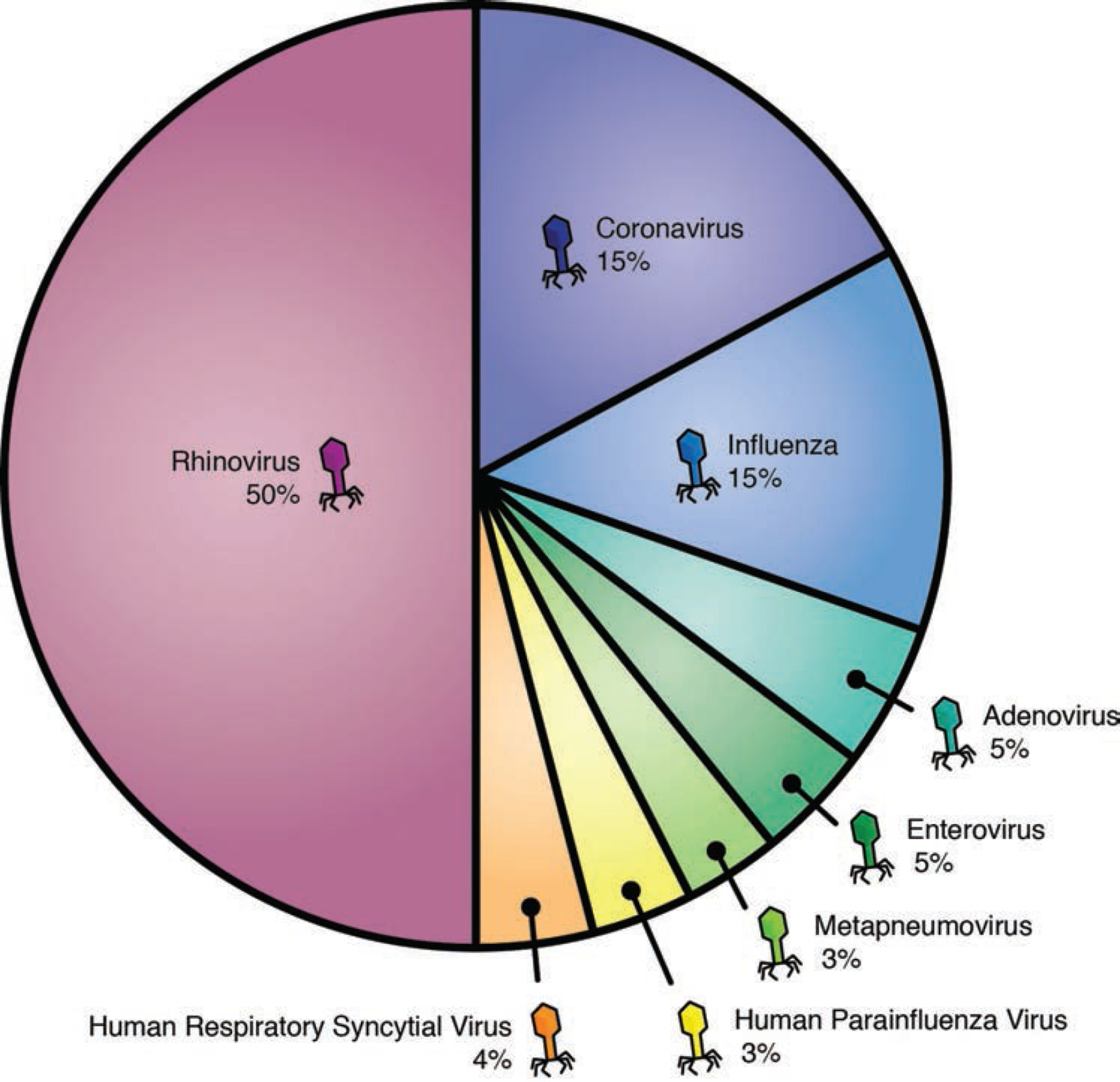

MANY DIFFERENT COLD VIRUSES MAKE US SICK

Unlike some viruses, such as the chicken pox, which is typically contracted only once, the common cold can be caught over and over and over (and over and over). There are more than 200 different types of cold viruses that can make you sick.

Even if you successfully suffer through and fight off one cold, there are a slew of other viruses ready to attack you as soon as you get better—often in succession, with no break in between. As previously stated, most kids will get 6–8 colds per year; for those who attend a daycare-type setting, the number can be even higher, ranging between 8 and 12 colds per year (or more).

As you get older, and your body has encountered and successfully combated many of the different cold viruses, your immune system will become wiser and more experienced. Unfortunately for children, this wisdom and experience can only come by going through the numerous battles. It may take several years before the frequency of yearly colds begins to mitigate.

COLDS ARE MORE PREVALENT DURING THE WINTERTIME

Cold viruses tend to travel and spread more easily when the humidity is low, which is most common during the wintertime. Viruses can be passed via surfaces such as door handles, keyboards, and shopping carts. People also tend to congregate indoors more frequently during the wintertime, thus increasing the transfer rate of viruses. For this reason, the bulk of colds kids will catch happen during the winter months.

The cold temperature itself does not make you sick. Cold weather leads to decreased humidity and indoor crowding, which subsequently increases the transfer of cold viruses. If no cold viruses are passed from person to person, regardless of how cold it is, you will not become sick.

That being said, although the cold weather by itself cannot make you sick, new research suggests that the cold weather may make it easier for cold viruses to replicate within your body. The cold weather may also weaken your immune defenses, making it easier for the cold virus to invade your body.

So, perhaps there is some truth to grandma telling you to bundle up during the wintertime so that you won’t get sick! Remember, though: No matter how cold it is outside, it is the presence of the cold virus that precipitates the illness, not the cold weather itself.

THE COLD VIRUS IS SPREAD BY TOUCH, SNEEZES, AND COUGH

The cold virus is virtually everywhere during the fall and winter. Even the most diligent hand-washing family will still catch several colds every winter. It is an unavoidable part of life.

The typical cold virus is picked up when your hand touches a surface that was previously infected by another person. The cold virus is now on your hand, and subsequent contact with your nose, mouth, or eyes will give the virus an entryway into your body.

Cold viruses can also attack through the air. When someone with a cold sneezes or coughs, the expelled saliva carries cold viruses through the air, with the potential to infect surrounding people.

The high prevalence of the cold virus makes it nearly impossible to avoid the common cold during the wintertime. The good news is that colds are not dangerous (unless complications ensue), and the act of your immune system fighting off a cold is actually healthy and beneficial for the body.

Of course, practicing good hygiene habits, while not a perfect defense, can still reduce the overall number of colds and other germs that a family catches throughout the year. A good habit to teach your kids is to wash their hands regularly for the duration of the “Happy Birthday” song, and to dry them thoroughly afterward. Children should also be taught to sneeze into their elbows rather than their hands, to reduce the transmission of germs to others.

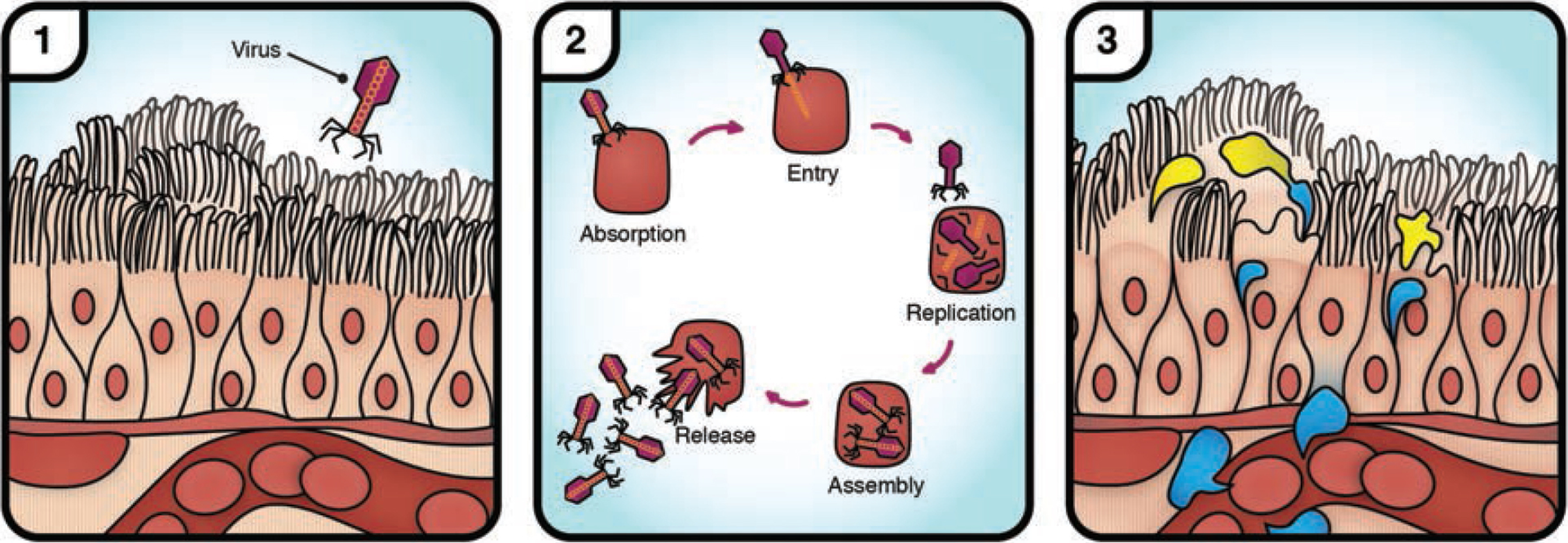

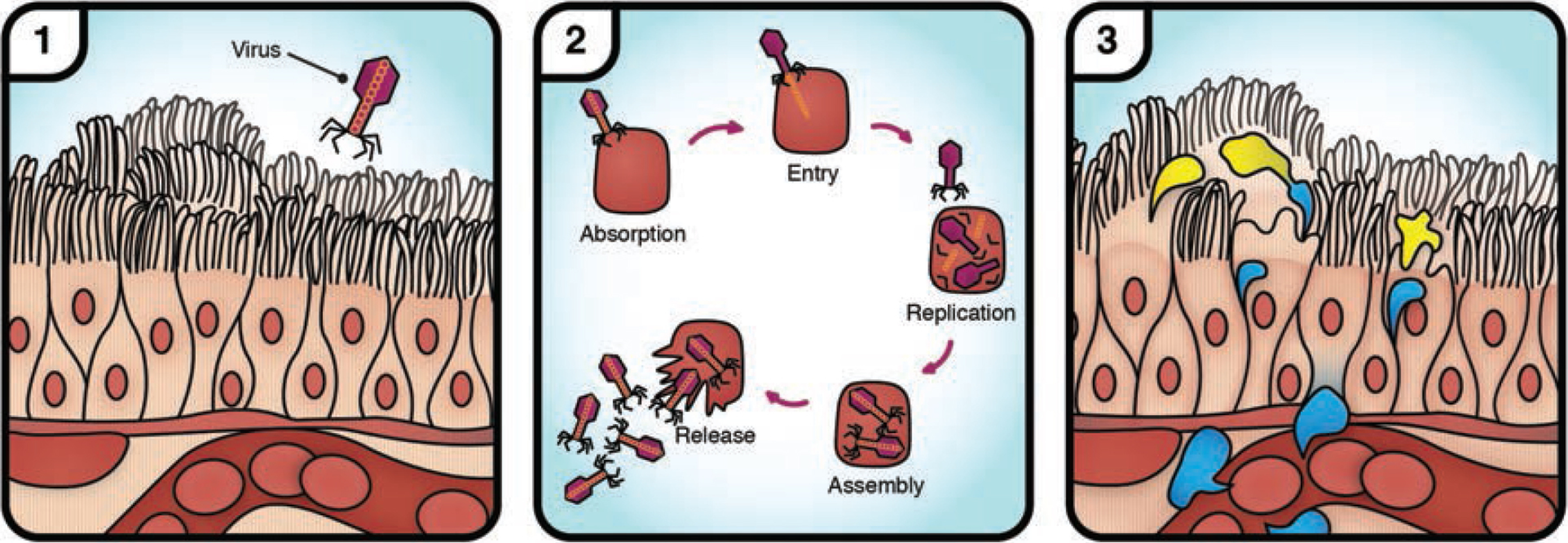

HOW THE COLD VIRUS DAMAGES THE INNER SKIN CELLS

Once the cold virus infiltrates your body through your nose, mouth, or eyes, it begins its work of reproducing itself by taking over your inner skin cells. Through a constant process of infiltrating and replicating, the cold virus destroys many of the body’s cells in the area of infection.

When you fall down and skin your knee, no amount of medications will accelerate the healing process of the knee’s skin—it takes time for the new skin cells to grow back! In the same way, when a cold virus destroys the inner skin cells in your nose, throat, or eyes, no amount of medication is going to accelerate the healing process. Healing will happen with time, but there will be mucus and irritation until the skin is restored.

There are many cough and cold medications that claim to help relieve the congestion and cough associated with the common cold. Decongestants purportedly reduce nasal congestion by shrinking the blood vessels in your nose, so that less mucus is produced, while cough medications are supposed to act on the cough center in our brain to depress the cough reflex.

Neither group of medications helps the healing process, nor have they been proven to work in children. Furthermore, many of these medications are actually known to trigger dangerous side effects. For these reasons, cough and cold medications should never be given to children.

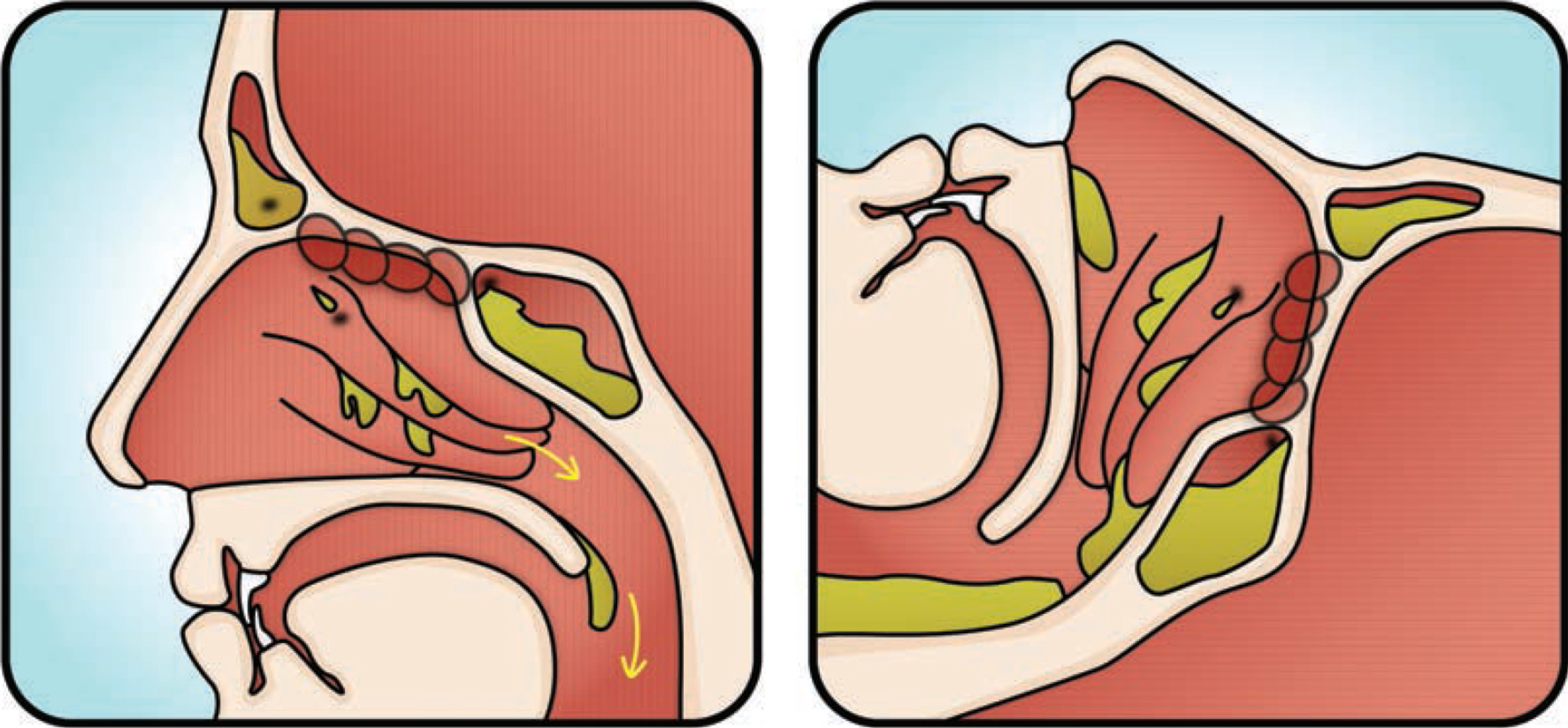

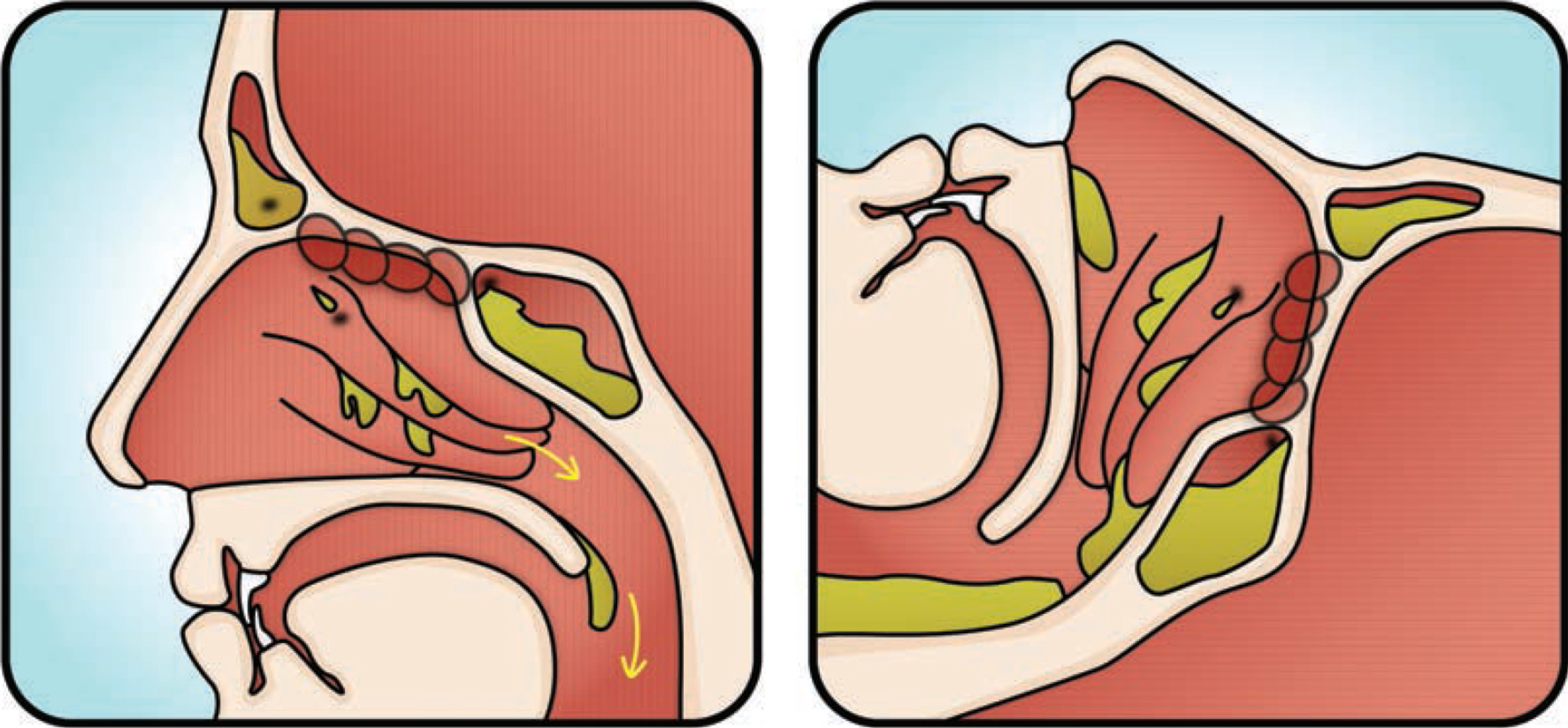

POOR DRAINAGE OF MUCUS MAKES COUGH WORSE AT NIGHT

Because we are vertical during the day, mucus drains down the throat and coughing is kept at a minimum. However, at night when we are lying down, mucus pools in the back of the throat, making it hard to breathe and triggering nighttime coughing. The typical pattern parents observe are periods of sleeping interrupted by bouts of heavy coughing throughout the night.

What is happening is that, after lying down, the back of the throat slowly fills up with mucus, like a swimming pool being filled with water. Once the pool of mucus reaches a certain threshold point, the body triggers a bout of coughing to help protect the airway from being inundated with fluids, after which the cycle repeats itself all over again.

Remember, medications do not help control the mucus and are not safe for children—particularly those younger than the age of 6 years. Some safe things can be done for comfort, but it is important to bear in mind that ultimately, time is the great healer.

1. Suction the nose as often as the child will tolerate to help keep mucus to a minimum. Electronic devices and those powered by the sucking power of a parent’s mouth can be particularly helpful. Nasal saline drops can be used to help break up the mucus for easier suctioning.

2. Keep children upright or have them sleep at an angle at night to help gravity move the mucus downward. For older children, this can be done by using an extra pillow or two. Discuss some safe options for your baby with your doctor.

3. A humidifier at night may help mask the tickling feeling in the back of the throat and may also keep the mucus from becoming too thick.

4. For children over 1 year of age, 1–2 teaspoons of honey can be given as often as needed and may also help mask the tickling feeling in the back of the throat. (Do not give honey to children younger than 1 year of age because of the risk of botulism.)

5. Make sure you keep your child well hydrated with plenty of fluids. A bowl of grandma’s chicken noodle soup never hurts, and the steam may even help to break up the mucus.

THE COMMON COLD TIMELINE

Not only will your child catch six to eight colds a year or more, but each cold will typically take at least two weeks or longer to resolve.

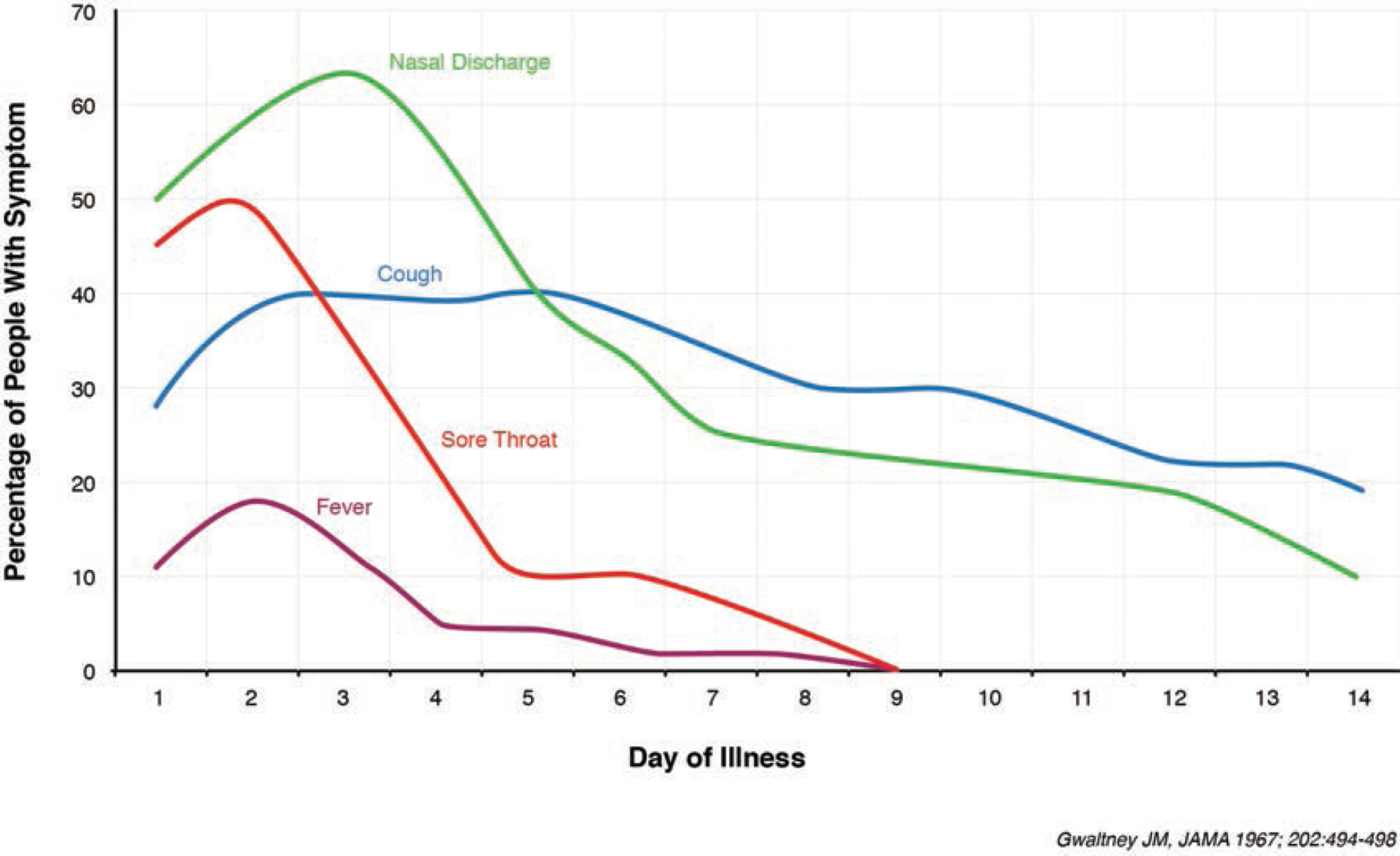

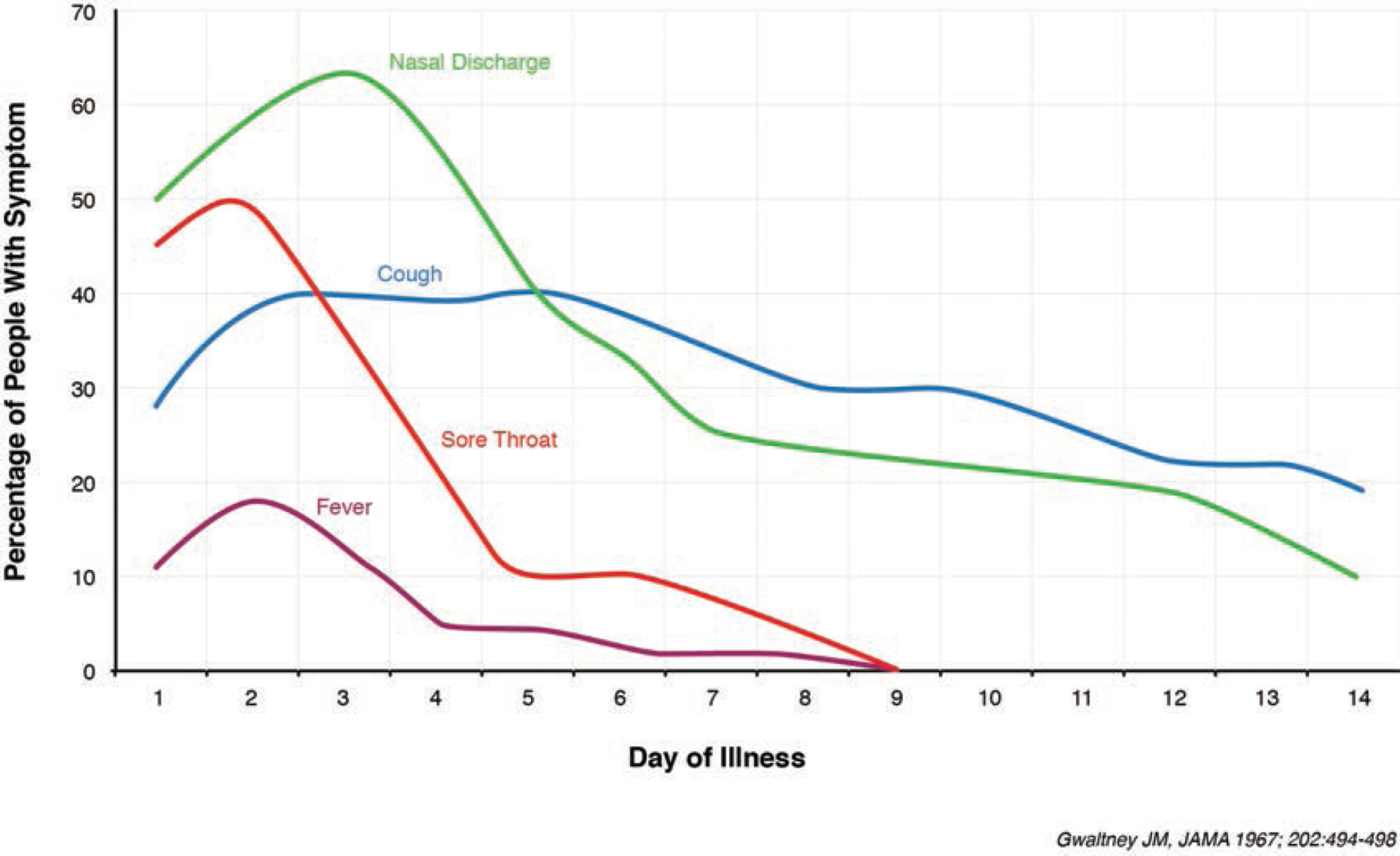

Fever will usually resolve within three to five days, but it is also not unusual for a fever to last seven to nine days. To be cautious, though, any fever lasting longer than three days should be evaluated by a doctor to make sure there is not a secondary infection brewing.

In other words, although a fever may just be caused by a cold virus by itself, there is a chance that a prolonged fever is representative of a cold that is becoming further complicated by an ear infection, a sinus infection, or pneumonia.

Sore throats will typically resolve in five to seven days. A sore throat that is worsening over time or lasting longer than five days may need to be seen by a doctor.

Congestion and coughs will typically take one to two weeks or longer to improve; however, it is not unusual for a cough to last three to six weeks with a single cold. If a cough is lasting longer than two to three weeks and does not sound like it is improving, it may be worthwhile to have a doctor listen to the lungs to make sure there are no asthma-like issues present.

However, if there are no signs of asthma, there is little that can be done for prolonged coughing. If asthma issues are actually complicating the cold, there are some things that should be done to help control the cough and improve the breathing (see here for more details).

Remember—with the common cold, time is the great healer!

EXPECT MULTIPLE COLDS PER WINTER

Most children will catch one cold per month during the winter months, typically starting in October and lasting until March. It may seem like your child is a perpetual mucus-producing, coughing machine for nearly six months straight, with just an occasional break from symptoms here and there. Believe it or not, that is pretty typical!

It is safe to estimate that your child will spend 80 percent of the wintertime with a cough, congestion or both, especially in the first few years of life. (And you, as the parent, may also feel like you are sick for much of those first few winters!)

A good number of children will suffer from several ear infections as well. While colds cannot be treated, most ear infections can. When an ear infection (see Chapter 5) is suspected, the child should be seen by the doctor. It is also important to be on the lookout for pneumonias and asthma-like issues. Each of these complications and their specific symptoms will be discussed in later chapters.

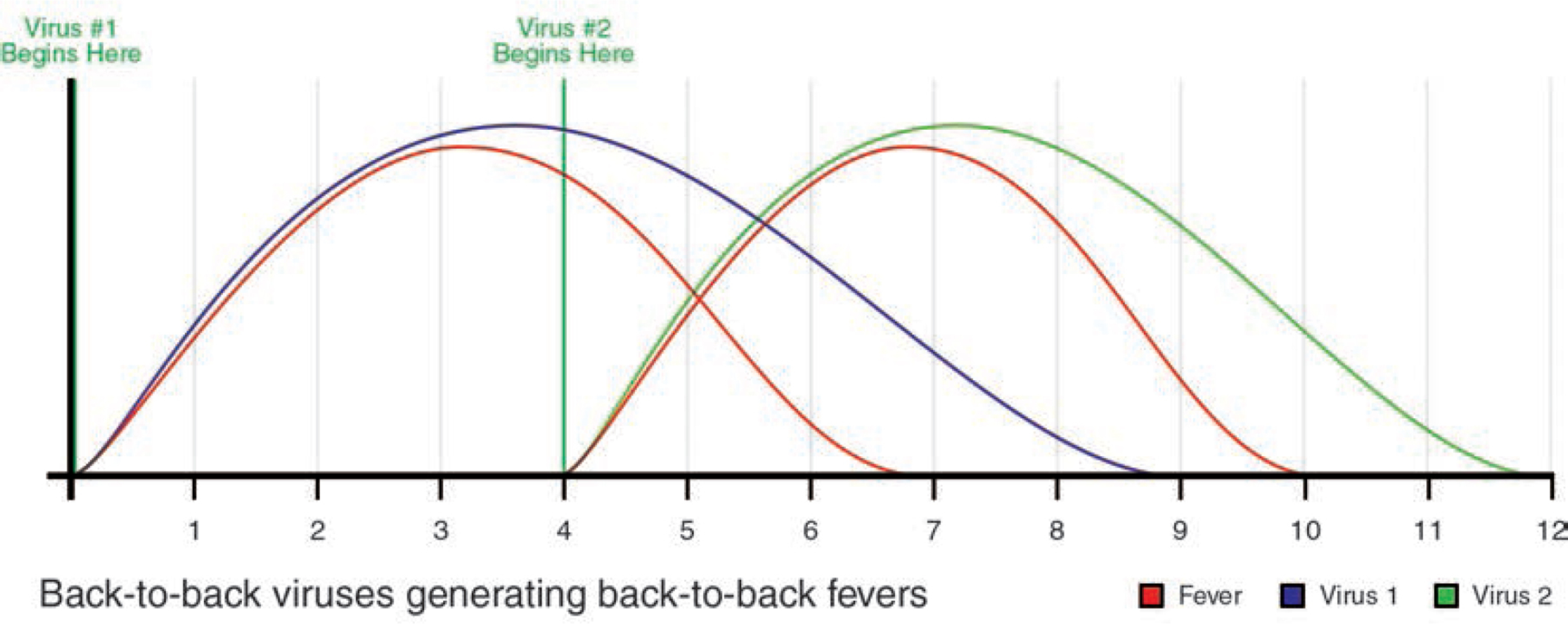

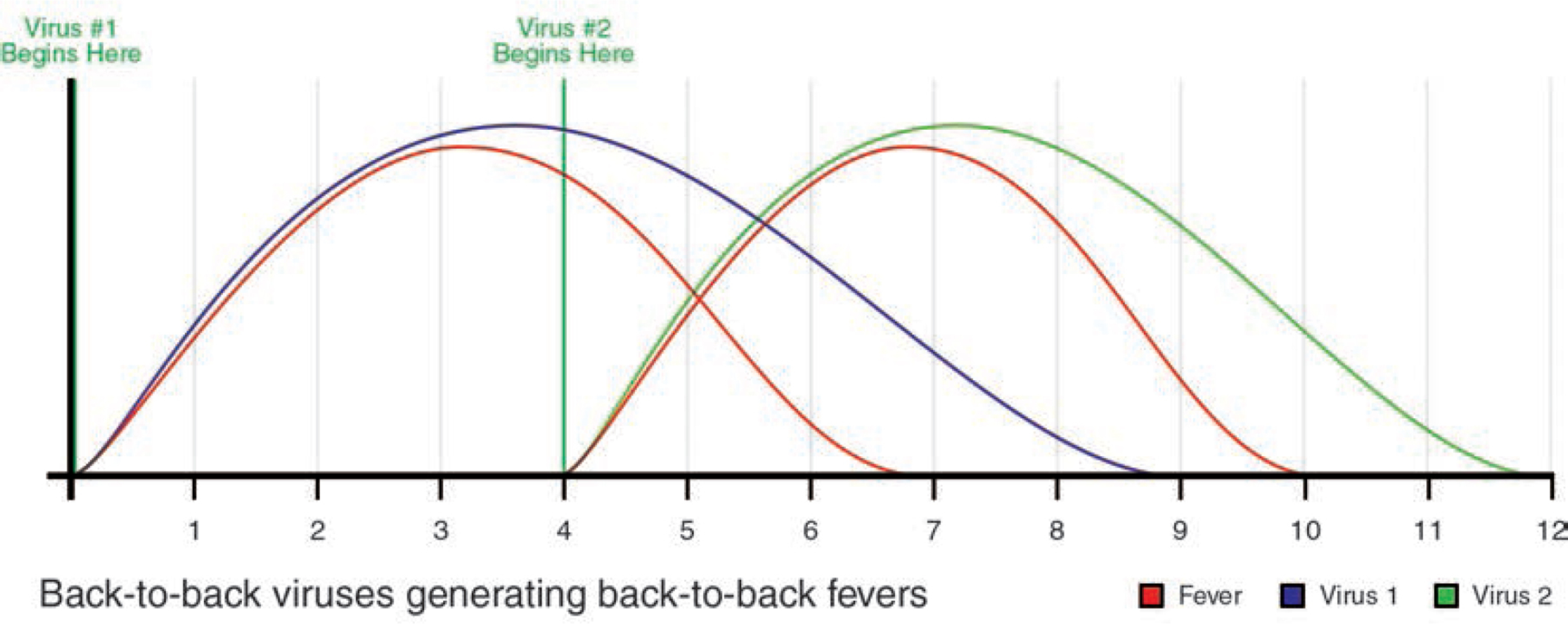

THREE REASONS FOR BACK-TO-BACK FEVERS

Children will regularly have fevers throughout their life. However, some children may occasionally have back-to-back fevers, when a fever starts, appears to resolve, and then comes roaring back.

There are three typical scenarios which can explain this phenomenon:

The first scenario is one in which a virus attacks the body and, as the immune system begins to defeat the virus, the fever begins to recede; however, the virus then makes a comeback, triggering a second fever. Eventually, the immune system will conquer the virus and the fever will fully resolve.

The second scenario is where a virus attacks the body and, as the immune system begins to defeat the virus, the fever begins to recede; subsequently, a different virus will attack the body and trigger a second fever. Eventually, the immune system will conquer both viruses and the fever will fully resolve.

The third scenario is where a virus attacks the body and, as the immune system begins to defeat the virus, the fever begins to recede; subsequently, a bacterial infection (following the initial viral infection) triggers a second fever. Eventually, the immune system will conquer the virus (the bacteria will usually require antibiotics) and the fever will fully resolve.

Generally speaking, any child with back-to-back fevers should be seen by the doctor to ensure a bacterial complication is not settling in. Ear infections, sinus infections, and pneumonias caused by bacteria often require antibiotics and close follow-up care.

WITH A COMMON COLD, APPETITE LOSS IS TEMPORARY AND COMMON

A loss of appetite will accompany most illnesses. It takes energy to digest food; when your child is sick, their body will purposefully stop eating so that it does not have to use energy on the digestive process.

The body has plenty of fat reserves that can temporarily provide energy for the body. The saved energy from not having to digest food will be used to help fight the invading germs. This allows the immune system to more efficiently and rapidly defeat the invading germs.

With most illnesses, a drop in appetite is to be expected, and is not worrisome as long as the child continues to drink plenty of fluids and is playful and interactive. However, if a decrease in appetite is also accompanied by a decrease in playfulness and a decrease in interaction, the child should be evaluated for the possibility of a more serious infection.

Appetite will usually inversely mirror fever: As the fever kicks in and rises, appetite will typically diminish, and as the fever fades and the germ is defeated, appetite will return to normal.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN AN ALLERGY AND THE COMMON COLD

Doctors are often asked how to tell the difference between the common cold and an allergy. The short answer? It’s not easy.

Colds and allergies both manifest themselves with mucus, sneezing, cough, and congestion. In general, colds tend to have more cough and mucus symptoms, and allergies tend to have more sneezing and itchy eye symptoms.

When a cold virus invades the mucus membranes, it destroys the inner skin cells of the nose and throat, which in turn leads to sneezing, cough, mucus, and congestion. Allergies, on the other hand, occur when allergens (such as pollen) invade the nose and throat, triggering the release of histamine from mast cells, which then leads to sneezing, cough, mucus, and congestion.

Histamine release only occurs with allergies; as such, oral antihistamines will only relieve allergies, and not colds. Thus, one simple way of differentiating between colds and allergies is to give an oral antihistamine daily for 1–2 weeks. If there is an appreciable improvement in symptoms, allergies are likely part (or all) of the underlying problem.

During the wintertime, it is quite possible that children may be afflicted with a cold virus and allergy issues at the same time. When this happens, allergy medications will provide some relief, while the symptoms resulting from the cold will not respond to the allergy medications and will have to run their course over time.

It is important to note that most kids will only develop seasonal allergies after they have been exposed to the same allergen two or three seasons in a row. Hence, most children younger than 2–3 years of age are unlikely to have allergy issues.

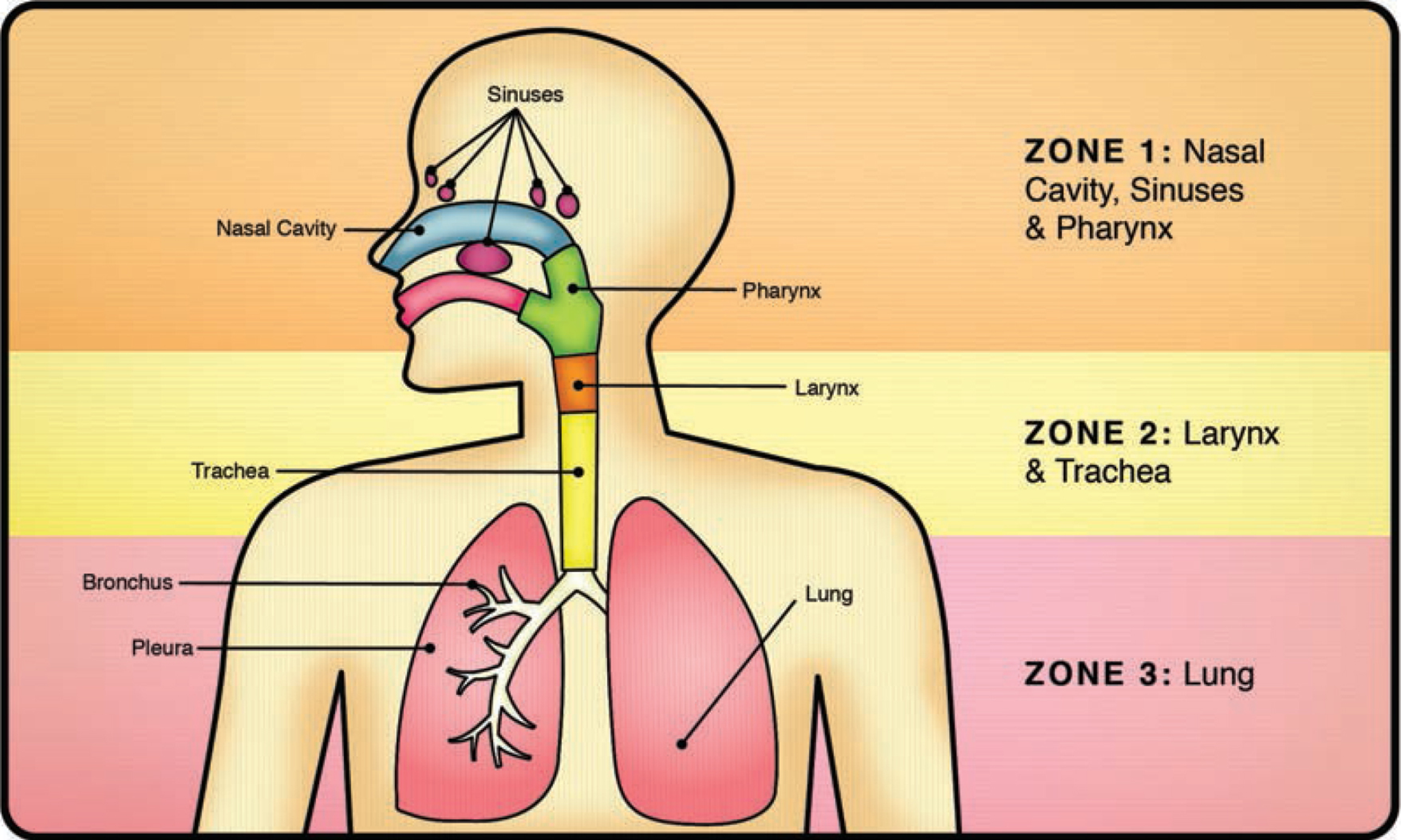

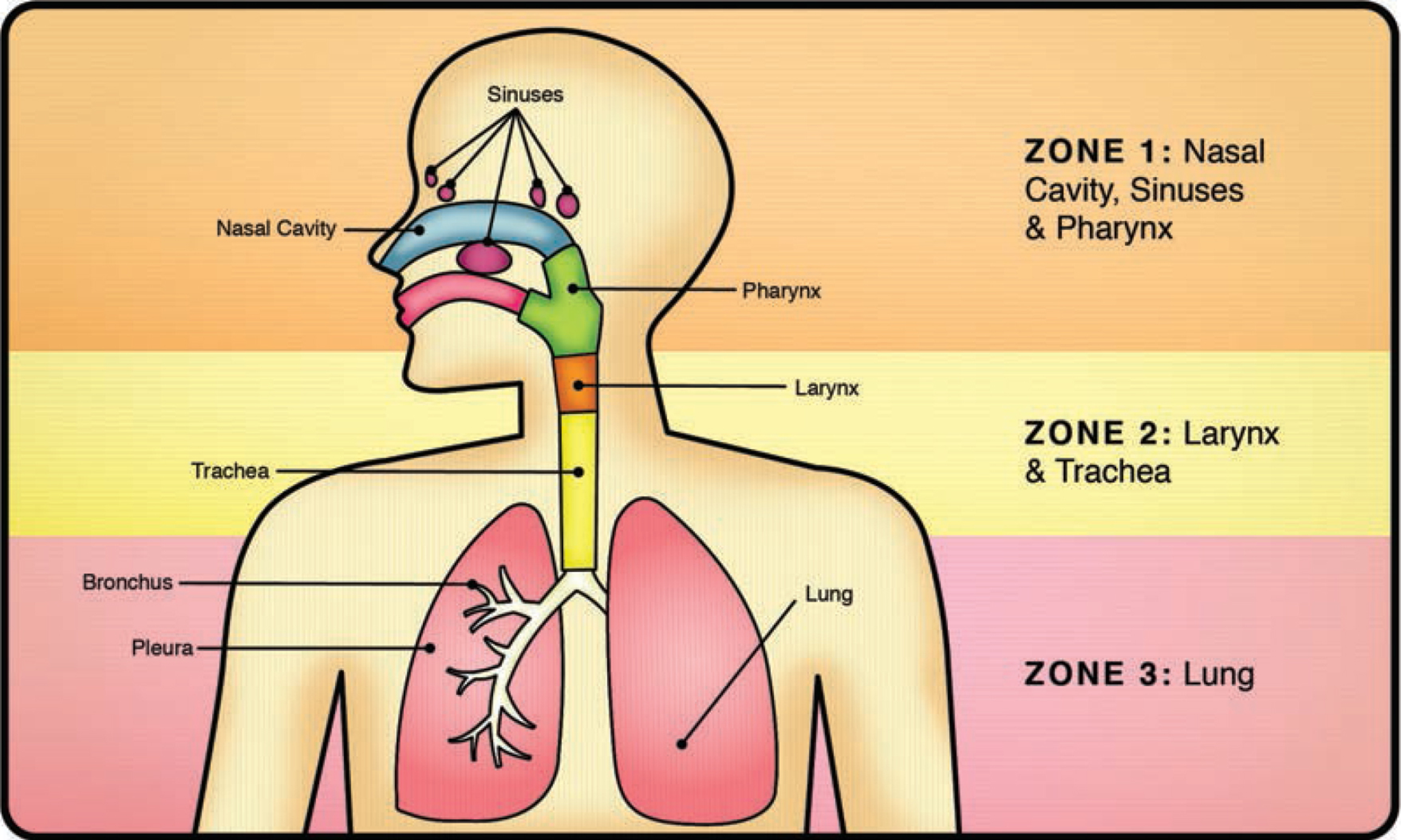

LOCATION MATTERS WITH THE COMMON COLD VIRUS

As mentioned in the first chapter, location matters! When we think of cold viruses, we think of mucus, cough, and stuffy noses. However, different types of diseases and symptoms can result based on where the cold virus infects the airway of the child. In other words, the same germ can manifest itself in many different ways, depending on where in the respiratory tract it takes a foothold.

Picture a classroom, in which all the students pass around the same exact cold virus. Jack’s cold virus may deposit in his throat, triggering a viral throat infection (pharyngitis). Sally’s cold virus settles in her eyes, precipitating a viral pinkeye (conjunctivitis). Sam’s cold virus may block his eustachian tube, which then allows a streptococcus bacteria to fester in his middle ear space, leading to a middle ear infection. The germ remains the same, yet the symptoms differ depending on where the germ makes its home in the body.

The following pictures in this chapter present the different inflammatory complications that a cold virus can elicit. The various clogging complications are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6.

NASAL INFLAMMATION (RHINITIS)/VIRAL SINUS INFECTION (SINUSITIS)

If the cold virus invades the nasal cavity area, the result is nasal inflammation (rhinitis), or what is better known as the common cold. Common colds are characterized by cough, sneezing, runny nose, sore throat, congestion, and fever.

The cold virus can also invade nearby sinuses (not shown) and trigger a viral sinus infection. Viral sinus infections are far more common than bacterial sinus infections. Unlike a bacterial sinus infection (discussed in Chapter 6), a viral sinus infection does not require antibiotics.

Green mucus is triggered by an enzyme called myeloperoxidase and is present with both viral and bacterial infections. As such, the presence of green mucus is a poor criteria in determining whether antibiotics are needed or not.

THROAT INFECTION (PHARYNGITIS)

If the cold virus invades the throat area, the result is a sore throat (pharyngitis), which often accompanies a common cold. Throat infections caused by a cold virus do not require antibiotics, unlike a strep throat (streptococcal phayrngitis), which does.

Approximately 85 percent of throat infections are caused by viruses, which means they are far more common than a strep throat infection. A viral throat infection will heal on its own, but may benefit from gargling with salt water several times a day as needed; otherwise, only supportive care is needed.

Collectively, rhinitis, sinusitis, and pharyngitis are known as upper respiratory infections.

CROUP/LARYNGITIS

If the cold virus invades the vocal cords or windpipe (trachea), the result is croup. Croup is characterized by a loud, barky cough. Although croup can look and sound quite dangerous, it rarely is.

Croup will often produce a stridor breathing sound in the child which mimics wheezing. Stridor is a high-pitched, musical breathing noise heard with inspiration of the lungs, whereas wheezing is more of a whistling sound heard with expiration of the lungs. If wheezing is present, it indicates involvement of the lungs, which is more concerning and should be reported to the doctor.

Croup can be treated with oral steroids at the doctor’s office to help decrease the inflammation in the vocal cords and windpipe. Home remedies include giving the child a 15-minute steam bath, or stepping outside with the child for a short walk. Most kids quickly improve from croup, with minimal intervention being needed.

Another symptom of the vocal cords being invaded is laryngitis, which is characterized by a loss of voice. Laryngitis will resolve in time and requires little intervention other than resting the vocal cords.

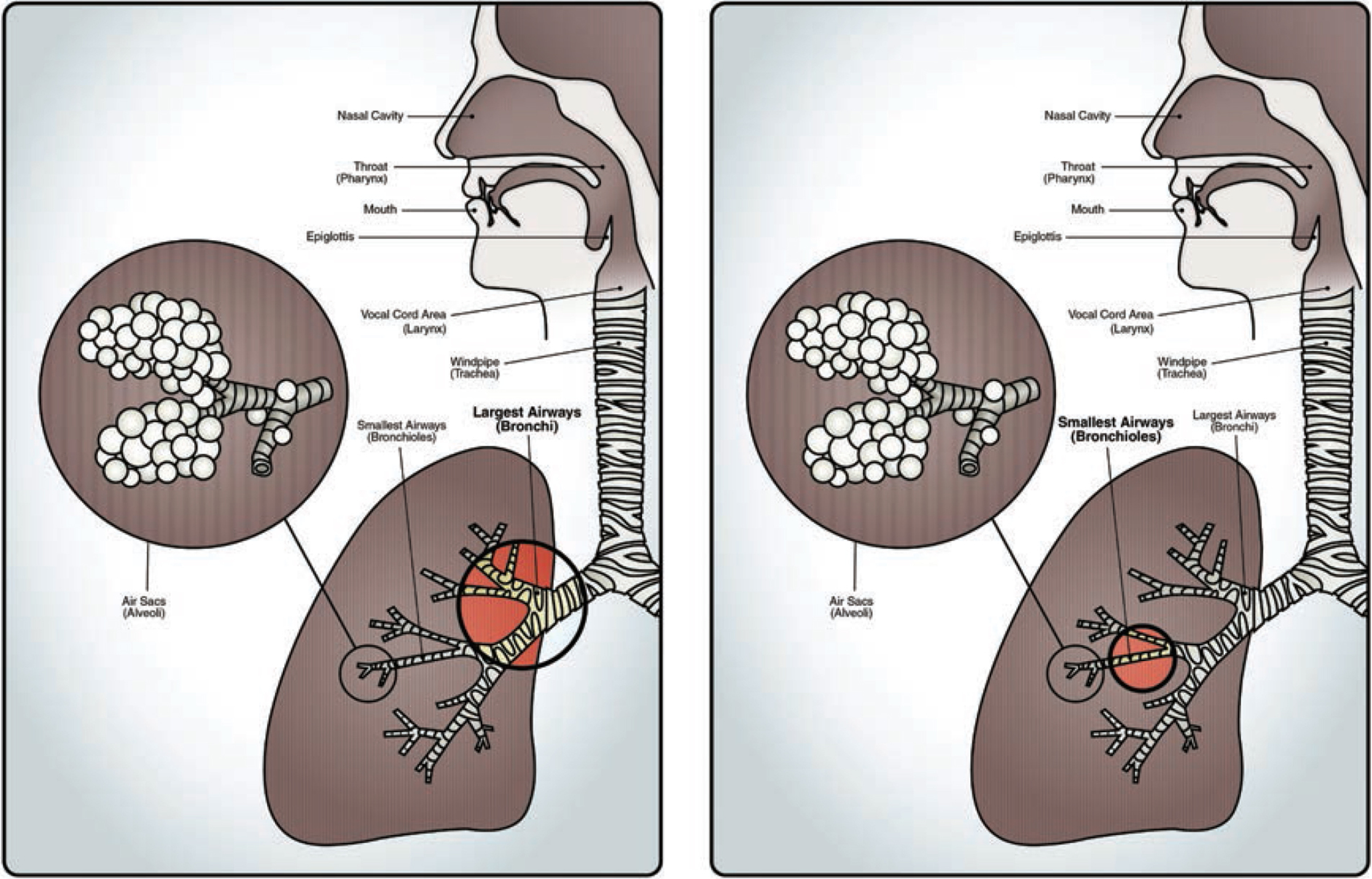

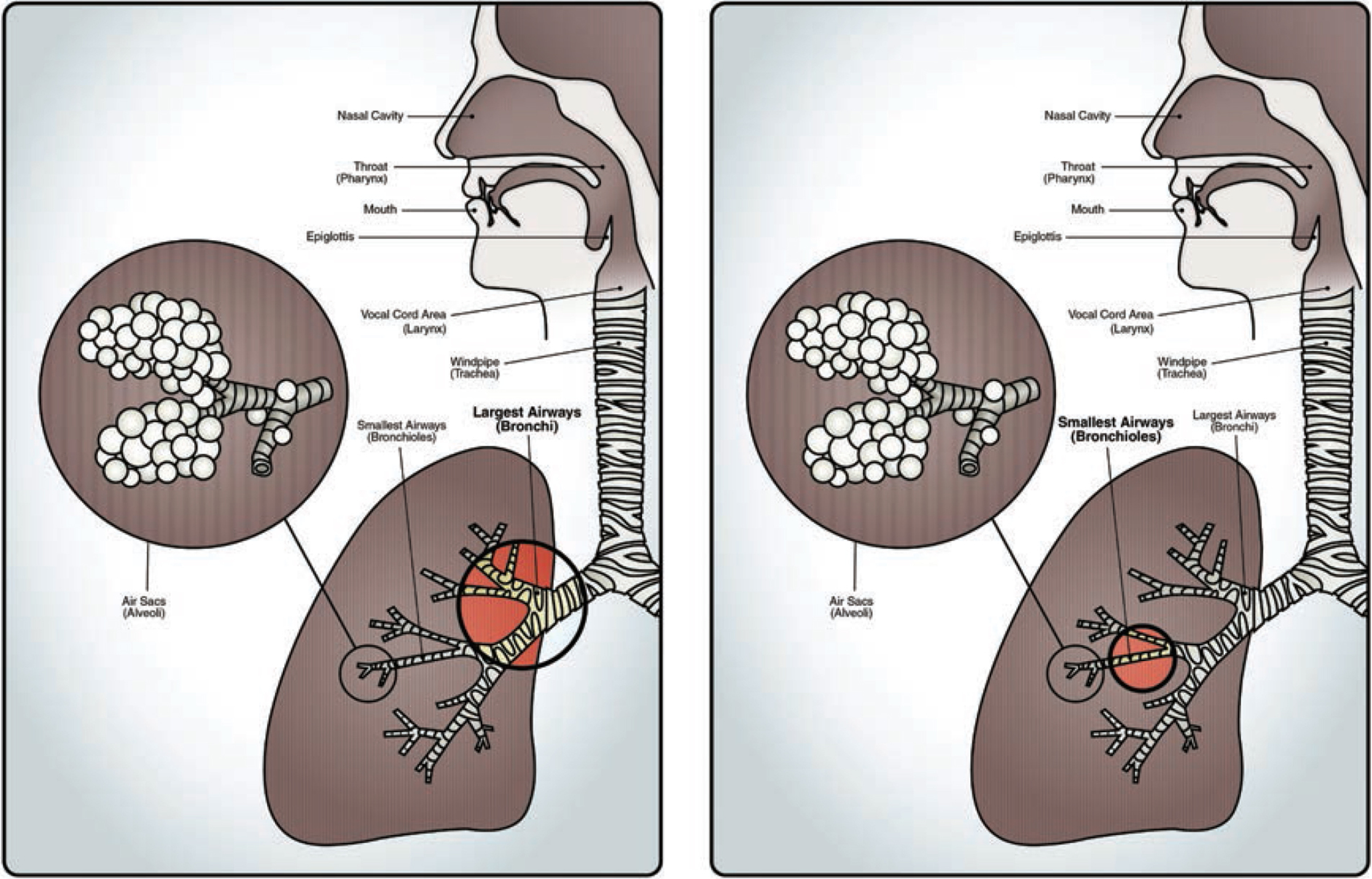

BRONCHITIS/BRONCHIOLITIS

If the cold virus migrates all the way down into the lungs, it can infect and inflame the airways. Large airways are called bronchi, and when they are infected, it is called bronchitis. Bronchitis is more common in adults. Small airways are called bronchioles, and when they are infected it is called bronchiolitis. Bronchiolitis is more common in young children younger than 2 years of age.

When the airways become infected, wheezing often accompanies the mucus and inflammation of the airway walls. Imagine the same mucus and stuffiness you feel in your nose happening further down in the airways of your lungs.

Bronchitis and bronchiolitis are almost always caused by viral infections, yet doctors often over-prescribe antibiotics for these illnesses. Unfortunately, this will not help. Asthma medications (such as steroids and inhalers) are also prescribed by doctors, but provide limited benefits, and only help when the child actually has an underlying asthma problem.

Similar to the common cold, the main problem with bronchiolitis is the damage to the airways caused by the virus itself. Full recovery can take weeks or even months. In young children, hospitalization may be necessary for observation purposes and supportive care (such as oxygen).

If a child is displaying labored breathing or decreasing activity, they should be evaluated by a doctor. Most kids will recover and return back to normal with time, but be prepared for a very long period of coughing.

As a side note, the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most notorious of the bronchiolitis-causing germs, but it only comprises 25 percent of cases, with other cold viruses rounding out the rest. Whether bronchiolitis is triggered by RSV or a different virus, the symptoms and treatment are the same as described above.

VIRAL PNEUMONIA

If the virus makes it all the way down into the air sacs of the lung (known as alveoli), a viral pneumonia can develop. Viral pneumonia can be cumbersome, and even dangerous in severe cases; however, the majority of cases are not, and most will resolve with time.

Like bronchiolitis, a severe case of viral pneumonia may require hospitalization for the purposes of observation and supportive care. If a child is displaying labored breathing (appearing as if they just ran a mile) or decreasing activity, they need to be evaluated by a doctor.

A bacterial pneumonia (discussed in Chapter 6) is more concerning than a viral pneumonia, and must be treated with antibiotics. Bacterial pneumonias will also display labored breathing and decreasing activity. A good physical exam and/or a chest x-ray (although often not needed) can differentiate between a viral and bacterial cause of pneumonia.

THE THREE ZONES OF THE AIRWAYS

| Zone 1: Upper airways | Nasal cavity, sinuses and pharynx (throat) | Common cold (rhinitis), viral sinus infection and sore throat |

| Zone 2: Middle airways | Larynx and trachea (windpipe) | Croup and laryngitis |

| Zone 3: Lower airways | Lungs (bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli) |

Bronchitis/bronchiolitis and viral pneumonia |

For a doctor evaluating a child with a respiratory virus, the most important distinction is to determine whether the infection is affecting the upper/middle airways and/or the lower airways. An infection involving the lower airways (Zone 3) is always more concerning, because compromised lungs may lead to life-threatening complications and as such may require oxygen supplementation and/or closer monitoring in a hospital. A child with an upper/middle airway issue (Zones 1 and 2) will typically get better on their own, and generally do not need to be seen by a doctor other than for reassurance purposes (and oral steroids for croup).

There are two clear signs that a child’s lower airways are becoming involved:

1. Retractions: With each breath, the chest will appear as if it is sinking just below the neckline and/or under the ribcage. The child will breathe as if they just ran a mile. A few minutes of retractions are not too worrisome, but sustained retractions for one hour or more warrant a call or visit to the doctor.

2. Increased Breathing Rate: Count the number of breaths over one minute. If the child is breathing faster than the age-appropriate normal rate for a period of one hour or more, call the doctor.

| Age | Normal Respiratory Rate |

| Normal rates: Infant (birth–1 year) | 30–60 |

| Toddler (1–3 years) | 24–40 |

| Preschooler (3–6 years) | 22–34 |

| School-age (6–12 years) | 18–30 |

Other concerning signs of lower airway involvement include flaring of the nostrils, grunting noises, wheezing noises and changes in the color of complexion (pale, gray, or blue).

Bear in mind that the above chart does not include the bacterial infections that can result from a clogging complication of any of the above viral infections. Refer back to here for a better overview of the different bacterial manifestations that can follow a viral infection.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

![]() There are no effective cough and cold medications for children.

There are no effective cough and cold medications for children.

![]() There are two major categories of common cold complications: inflammatory complications and clogging complications.

There are two major categories of common cold complications: inflammatory complications and clogging complications.

![]() Most kids will catch at least six to eight colds per year.

Most kids will catch at least six to eight colds per year.

![]() Coughing is more copious at nighttime due to poor drainage of mucus when lying down.

Coughing is more copious at nighttime due to poor drainage of mucus when lying down.

![]() Full recovery from the common cold can take two weeks or longer.

Full recovery from the common cold can take two weeks or longer.

![]() For a common cold, time is the great healer.

For a common cold, time is the great healer.

![]() Back-to-back fevers should be evaluated by a doctor.

Back-to-back fevers should be evaluated by a doctor.

![]() Allergies and colds are similar in appearance, but an antihistamine trial may help discriminate between the two.

Allergies and colds are similar in appearance, but an antihistamine trial may help discriminate between the two.

![]() Location matters! Depending on where the cold virus invades, different symptoms and diseases can occur.

Location matters! Depending on where the cold virus invades, different symptoms and diseases can occur.

![]() Think of the airway in three zones: upper, middle, and lower. Cold viruses can cause unique complications in each zone.

Think of the airway in three zones: upper, middle, and lower. Cold viruses can cause unique complications in each zone.

![]() Lower airway infections are cause for concern, and the sustained presence of retractions and/or increased respiratory rate warrant a call to the doctor.

Lower airway infections are cause for concern, and the sustained presence of retractions and/or increased respiratory rate warrant a call to the doctor.

The cold virus is ubiquitous, making it impossible to avoid during wintertime. Children will catch their fair share of cold viruses no matter how careful and hygienic they are. Depending on where the virus invades, different symptoms and diseases will occur.

Most inflammatory complications of the cold virus will require minimal intervention and will typically resolve with time and supportive care.

Should a child present with labored breathing, decreased activity, or back-to-back fevers, a visit to the doctor is warranted. For the most part, most colds and their inflammatory complications can be handled at home with some tender loving care and time.