While I am not so foolish as to make rash assertions about these things [i.e., the substantial nature and possible immortality of the soul], still I do claim to have proofs that the forms of the soul are more than one, that they are located in three different places . . .

—GALEN OF PERGAMON

Every era is unique, but our age is unprecedented in that for the first time in recorded human history, the myths and spiritual teachings of almost every living tradition have become accessible to all as a common cultural treasure. One hundred years ago, the Rigveda, an ancient Indian sacred collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns and one of the oldest religious texts (ca. 1700–1100 BCE) in continual use in any Indo-European language was accessible to the curious mind, but information about the Hawaiian mystical Kahuna tradition, or about the worldview of the Inuit circumpolar peoples was entirely lacking. As always, many pieces of the overall human cultural spectrum are still missing, but the teachings derived from a wide variety of cultures about the Great Mystery of human existence can now be studied from different perspectives, and the cross-cultural similarities are stunning.

Ethnographic data collected over the last one hundred years has generated a fertile field for those interested in studying cross-cultural commonalities. Frecska and Luna (2006) have discussed why the ideas of soul, spirit, or rebirth echo across the ages and why these concepts repeatedly appear in entirely different cultures. The belief in the existence of soul(s), spirit guides, spiritual forces, and other worldly realms appears to be universal in the human species. Edward Osborne Wilson (1998) has noted that sociology has identified the belief in a soul to be one of the universal human cultural elements, and he has suggested that science needs to investigate what predisposes people to believe in a soul. With our coauthors, we have made efforts to overcome the typical rational interpretations that deem such ideas to be superstition, originating in delusion or the fear of death. We accept that these recurrent, prevailing themes (“elementary ideas”—as they were called by Adolf Bastian, one of the founders of ethnography) (see Koepping, 1983) are not just products of wishful thinking, and represent more than irrational coping mechanisms against the anxiety of ego-dissolution at death.

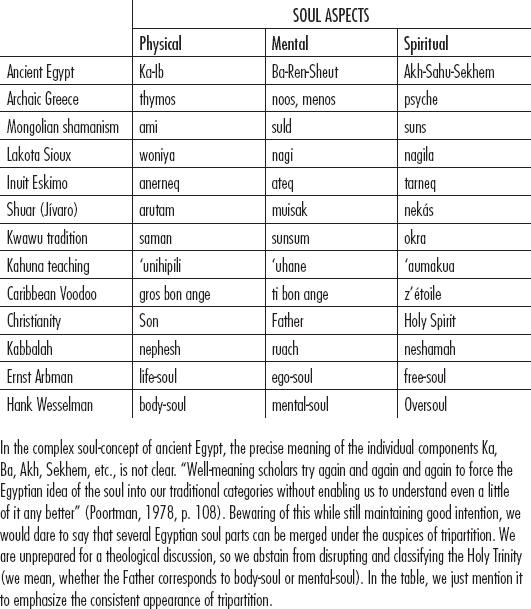

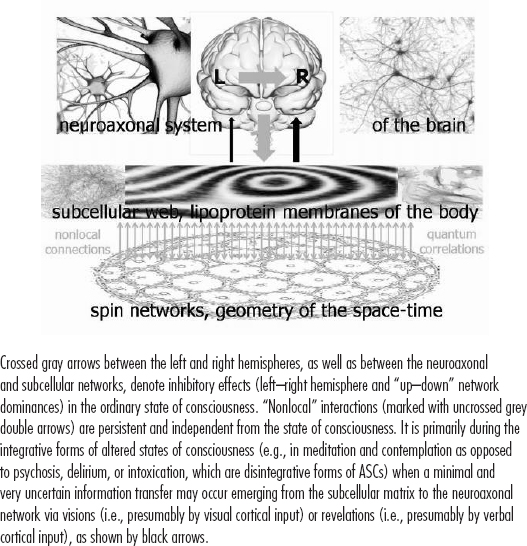

The focal point of the current paper is the observation that the concept of soul is noticeably complex in aboriginal cultures, and its plural—especially tripartite—nature is the rule rather than the exception. Curiously, this perception is getting clearer and more pronounced when one considers our shamanic origins. Herewith, we refer to Wilhelm Wundt (1920) who gave much attention to the point that the animistic perception of the soul is pluralistic. Among aboriginal groups, the term soul cannot be used as it is in the Western tradition because indigenous peoples widely hold the belief in multiple souls (or aspects) of a human being. There are advanced cultures where the number of principles defining the human essence is reduced to a number smaller than three (e.g., the duality of ling-hun in Chinese traditional medicine), but a thorough look reveals that such dualism (or monism) is a deflation of an earlier trinity (Harrell, 1979). Taoism, which has shamanic origins (Stutley, 2003), teaches that there are three souls, one of which remains with the corpse after death (like the Ka of the ancient Egyptians), while another resides always in the spirit world, and the third that transmigrates between the physical back to the spiritual realms. Shinto lore suggests the soul has multiple sections that can act and move around independently, so it may be that different parts have different afterlives—one being reincarnated, one becoming a guardian, etc. As far as advanced Mesopotamian civilizations are concerned, there seems not to have been any clear concept of a soul in neither Sumerian, nor Babylonian, and Assyrian religions. One may just speculate if these advanced civilizations have moved far from their source.

Swedish Sanskritist Ernst Arbman (1926/1927) analyzed the Vedic beliefs in India and found that the concept of the soul (atman) was preceded by a duality. In his analysis, Arbman separated the soul inhabiting the body and endowing it with life and action from the free-soul, an unencumbered soul-aspect embodying the individual's nonphysical mode of existence not only after death but also in dreams, trances, and other altered states of consciousness (ASCs). According to his classification, the free-soul doesn't have any physical or psychological attributes; it simply represents the immortal spiritual essence of the individual.

In this regard, Arbman addressed the issue of duality but implicitly wrote about tripartition since he combined two soul parts for which different cultures have separate names (see Table 1). In addition to the free-soul, the physical soul or body-soul is often divided into several components. Usually it falls into two categories, one of which is the “life-soul,” the vital force, frequently identified with the breath, while the other is the “ego-soul,” the source of thoughtful action and decision making. In the Vedic tripartite soul concept, the free-soul incorporated the psychological attributes of the bodysoul, a development that occurred among a number of other cultures.

One of Arbman's most gifted pupils Åke Hultkrantz (1953) followed his master's lead while studying Native American Indians and took the same stance, speaking about dualism while describing a trinity. Bremmer (1983) has addressed how multiplicity can be obscured by the focus of interest and the concepts of the soul held by the field investigators themselves. In this regard, Arbman and Hultkrantz were clearly more interested in the free-soul and in its evolution over time and accordingly paid less attention to the “life-soul” and “ego-soul” as independent entities. Their predecessors and contemporaries were also more interested in the myths of Afterlife than in tribal psychology. The main goals of this publication are: 1) to give a detailed analysis of ancient and indigenous soul concepts within the framework of tripartition, 2) to outline a dynamical relationship between the soul components, and 3) to provide a tentative “neuro-ontological” interpretation based on a biophysical approach.

The conception of the soul in Ancient Egypt was complex. The Egyptians conceived of a person's individuality as being made up of several independent beings, each of which was a distinct personality seen as a whole having a separate existence both during life and after death. Their belief system that appears to have been based in direct shamanic experience included a number of souls or soul aspects and auxiliary entities that together constituted the individual. According to Egyptian funerary texts, man was composed of a mortal body, the Kha, and at least three soul principles: the Ka, Ba, and Akh (Hall, 1965).

In addition to the Ka, Ba, and Akh, there were further principles, which make the comparison more difficult: the Ib (metaphysical heart center of compassion), Sheut (shadow aspect of the person), Ren (name soul aspect of the person), Sahu (spiritual body for the Akh), and Sekhem (spiritualenergetic entity dwelling in the Afterlife in association with Akh). An interesting parallel can be noticed here with the Taoist conception of the “immortal spirit body.”

Accordingly, it can be observed that the ancient Egyptian soul concept is an example of the inflation of the number of soul aspects: In comparison to other traditions (Table 1), a segregation and transformation of soul elements is presumable. The idea of an independent and pure immaterial existence was so foreign to Egyptian thought that it assigned spiritual body (Sahu) and spiritual force (Sekhem) to the potentially eternal soul form (Akh), and delegated the other soul forms (Ka and Ba) for its help. It also seems that by Sekhem, ancient Egyptians introduced a complementary, ethereal version of the “life-soul” (vital force) by granting it to the deceased person's Akh as an energetic force. After all, in Egyptian cosmology, nothing existed in isolation, and duality was a norm.

The Christian worldview is monistic, allowing for only one soul per human body. The Trinity applies only to God, but not to man. However, centuries before, there were many discussions of the pluralistic concept of the human soul. In the early Greco-Roman period, the mindbody problem was complex: On the one hand, there was the psyche (Greek), or anima or genus (both Latin), an unencumbered soul that survives death. The Greek concept of the psyche is confusing to Western investigators. While on the one hand, it can closely correspond with Arbman's free-soul, some regard the psyche as passive while the body is alive. Its presence is the precondition for the continuation of life, yes, but—following the Greek tradition—Western scholars hold that it has no connections with the physical or psychological characteristics of the individual. In other words, it doesn't carry over one's personal identity or memories after death but instead enters the Underworld as a shadow of the living person (Bremmer, 1983).

On the other hand, there was the Greek concept of the thymos, or in Latin animus or fumus, which is the seat of personal identity and personal memories, but which dies with the physical body. It is this soul part that is the seat of emotions. Unlike psyche, thymos was believed to be active only when the body is awake. Thirdly, noos was a soul form representing the intellect and generating the willful actions of the person. There also was a soul component called menos, which can be described as a momentary impulse of combined mental and physical agencies directed toward a specific act. It was said to be able to manifest itself in a berserk-like fury. After the Archaic Age (800–500 BCE), there was a gradual incorporation of thymos and the noos into the psyche, which made the latter the center of the self—the organ of both thought and emotion. Accordingly, Plato goes as far as to include all intellectual functions (originally belonging to the noos) into the psyche.

The resemblance of the Archaic Greek soul belief to that of most indigenous peoples (to be discussed) strongly suggests that it belongs to a type of tribal society consciousness in which the individual is not yet in the center of focus (Bremmer, 1983). It may also reflect the effect of a tradition based less on philosophical speculation but rather more on the direct experience of which shamans and tribal healers were masters. Hultkrantz (1953) cites Edward Tylor, the 19th-century scholar of comparative religion who observed that the belief in a personal supernatural aspect or soul formed the original foundation for religious awareness: “The material shows that the greatest importance should be ascribed to such experiences and observations for the development of the ideas of the soul.” Apparently, a “direct-intuitive approach,” “the second foundation of knowledge” (Strassman et al., 2007) is the source that was suppressed with the unfolding of Western civilization, dominated by Judeo-Christian overlay.

Lack of direct experience can partly explain—at least—that in our own time, the concept of the soul is one of the most ambiguous, confusing, and poorly defined of our human ideas. As the antipode of the material essence, it exists as an entity substantially different from the body. Within this concept, the soul is the principle of life, action, and thought, and in this framework, body and mind can depart from it and go on in separate paths (like in Hindu mythology) . . . or they cannot be separated but can be opposed to each other (as in the three Abrahamic religions). In other approaches, the soul designates the totality of the self, refers to every level of the individual, and represents both the essence and the wholeness of human nature.

In this essay, we are going to refer to it in the latter meaning.

Discovering the “true” nature of the self has always been part of the Great Mystery, for unless one understands who and what we are, one cannot experience the mantle of authentic initiation. In Western philosophy, the 5th century BCE Ionian philosopher, mathematician, and mystic Pythagoras was the first to express his ideas about this during the classical period, proposing that every human being has three principia: a physical aspect (body, or soma), an intellectual-emotional aspect (mind, or psyche), and an immortal spirit. Pythagoras's three principia have influenced numerous thinkers and philosophers across time—among them Plato, Aristotle, Galen of Pergamon, and the Renaissance physician Paracelsus. One must also keep in mind the Freudian “Id—Ego—Superego,” or the Jungian “conscious—subconscious—collective unconscious” personality models, both of which converge on this ancient perception.

Yet the tripartite division of human nature was probably recognized far earlier than Pythagoras since we can find its categorical depictions in the many millennia old shamanic traditions of the indigenous peoples. In fact, it is conceivable that the Greek philosopher himself was drawing on the shamanic traditions of tribal cultures. Christopher Janaway (1995) wrote: “The body of legend which grew around Pythagoras attributes to him superhuman abilities and feats. Some think these legends developed because it is more likely that Pythagoras was a Greek shaman.” Indeed, Aristotle described Pythagoras as a wonder-worker and somewhat of a supernatural figure. According to Aristotle and others' accounts, some ancients believed that he had the ability to travel through space and time, and to communicate with animals and plants, all features that link him with the shamanic tradition (Huffman, 2009). Herodotus and modern scholars (Dodds, 1951) admit that Greek civilization was greatly influenced by the shamanistic culture of the Black Sea Scythians in the 7th century BCE. Kingsley (1999, 2003) presents evidence through the fragmentary writings attributed to the 6th-century mystic and shaman Parmenides of Velia, a small town in southern Italy, that the shamanistic tradition (iatromantis) actually formed the foundation for Western thought and philosophy, one that Plato did not fully understand. Seen in this perspective, Pythagoras and his fellow “Pythagoreans” were most definitely practitioners and teachers in the shamanic foundation.

According to the view of the Kwawu people in Ghana, three soul categories animate each human being. “At the time of conception, blood and flesh come from the mother. The person's body comes from his mother, belongs to his mother's matrilineage, and ultimately returns to the Great Mother: Earth.” It is occupied by the bodily soul form saman. A person receives semen from the father at conception. By this medium, a child gets fertility and cleanliness. Cleanliness means morality in a spiritual sense, while fertility is closely linked to personality by them. The soul component associated to it is called sunsum. “In contrast to blood and semen that a child obtains at conception, the breath of life is received from the God2 at time of birth.” The soul part entering the body this way is called kra. Death means that kra is taken back by the God (Bartle, 1983).

Surprisingly similar to this African soul concept is that of the Mongolian shamanic tradition that also considers that people have three souls. According to the Darkhad shamans, one soul comes from the maternal side (the soul that governs flesh and blood), a second is a bone soul from the paternal side, and the third soul comes from the Spirit World. The third one, the immortal soul, transmigrates from the Spirit World to a fetus in the womb. After death, it stays for a short while in the body, and then later, seeing the light, it moves back to the Spirit World and, eventually, transmigrates back into another baby (Purev, 2004).

In other parts of Mongolia, the soul form ami is held to be the soul that enlivens the body. It is related to the ability to breathe—in other words to the breath. After death it returns to the Upper World in the form of a bird (like the Ba of the Egyptians). During an illness the ami soul may temporarily be displaced, but it does not leave permanently until death. Ami may reincarnate among the relatives of the dead person. The suld is the most individualized of the human souls. It lives in a physical body only once; after death it remains around the body for a while, and then it takes residence in the Middle World. The suns soul, like the suld, also contributes to the formation of personality, but it carries the collected experiences of past lives. The suns reincarnates and stays in the Other World between incarnations but may return as a ghost to visit friends or relatives. Among the two reincarnating souls, the suns usually bears the strongest past-life memories. The suns soul may also temporarily leave the living body and sometimes wander as far as the Lower World, which may require a shaman to negotiate for its return. This Mongolian tripartite soul concept clearly reflects the three-tier shamanic cosmology (Sarangerel, 2000).

Throughout Siberia, it is widely held that all humans possess at least three souls; some groups such as the Samoyedes believe there are more: four in women and five in men. Not every author agrees on the concept of multiple souls. Shirokogoroff is skeptical of this notion: “I believe that in some instances of very multiple souls . . . we have the ethnographer's complex, his creation and not that which exist in [the indigenous population's] mind” (Shirokogoroff 1935/1982, p. 54). Some sort of deculturalization process adds to the confusion: Western influences and missionary assimilations have greatly adumbrated the soul concept of numberless tribes. Even so, the examples above suggest that humanity's archaic culture—the hunter-gatherer culture—perceived the reality of the soul trinity over thousands of years, and the commonality, even perhaps universality of the tripartite soul concept is plausible. Like in the case of the shamanic cosmology: the three-tier view is the most common worldwide, despite numerous deviations (for example, the twelve-level worldview of the South American Yagua tribe) (Fejos, 1943).

The Puyuma people—indigenous in Taiwan—believe that each person has three souls, one of which resides in the head, and the other two reside on each shoulder. Chinese aborigines belonging to the Hmong tribes follow their ancient shamanic tradition and believe that each living body has many souls (not in full agreement on the numbers, though). For a newborn infant, one soul enters his or her body when he or she is conceived in the mother's womb. Another soul enters when the baby has just emerged from the mother's body and taken its first breath. A third one will have to be called on the third morning after birth. The first soul is the one that normally stays with the body. The second soul is free, it wanders; this free-soul causes a person to dream while asleep. The third soul is the protective soul that tries to protect its owner from harm (Symonds, 2005).

The Native American Lakota Sioux distinguish the woniya (physical self), nagi (cognitive self), and nagila (spiritual self). Similarly, the Inuit Eskimos separate three souls: an anerneq soul, which we receive with the first breath at the moment of birth, an ateq soul, which we get with our names after birth, and a tarneq, our immortal soul. The Caribbean Voodoo religion also differentiates three forms of soul: gros bon ange, ti bon ange, and z'étoile (Wesselman, 2008.)

The Shuar (Jívaro) headhunter tribe living in the Upper Amazon regions of Ecuador also believes in the trinity of the soul (Winkelman and Baker, 2008). In their culture, everyone bears a “true soul,” the nekás wakanl, which arises at the moment of birth. This soul resides in the blood of an individual, and therefore blood loss equates to partial soul loss to a Shuar. The “true soul” leaves the body when one dies, and it starts an immortal existence reliving the entire life of the individual that it belonged to. After reliving this life, it may become a forest demon, or after several transformations, it evolves into mist and in this form unifies with the cloud of every deceased person's “true soul.” The war-cultivating Shuars are pragmatically minded and preoccupied with their everyday warfare. Therefore, the “true soul” interests them the least among the three, since—they suppose—it has minimal effect on their actual affairs.

The second soul is the arutam wakanl, which brings vision (arutam), and provides protection to the person. This “protecting soul” is so important that no one can reach adulthood without it, and it has to be gained before puberty. To acquire this soul, a young Shuar boy must go out into the forest for a vision quest of about five days. It is the vision (arutam) that brings power and intelligence; it shields against malevolence and witchcraft. Over the course of a lifetime, a warrior acquires several “protecting souls,” or helping spirits that give him extra protection.

The third one is the “avenging soul,” the muisak wakanl, which takes the stage when an arutam bearer is murdered. The function of muisak wakanl is revenge. When an individual with arutam wakanl is killed, his “avenging soul” leaves through the mouth and proceeds to try to kill the murderer. Because the Shuars are frequently engaged in killing raids, it is important for them to come up with a mechanism to stop the “avenging souls” from coming after them. This is the reason why the shrunken heads (tsantsa) are made. Shrinking the head prevents the muisak from leaving the body, and covering it with charcoal blinds this “avenging soul.” Moreover, the preparation moves the power of muisak to the killer's family (for example awarding them with more food). However, the muisak means potential danger for the tribe even when it is incarcerated into the tsantsa, so after a while, they excommunicate it to its village of origin, or sell the head to someone passing by (e.g., a tourist). In the belief system of the Shuars, the three-soul concept serves a double function: the conservation of tribal warfare and the protection of the individual's well-being (Winkelman and Baker, 2008).

According to the view of Hawaiian aboriginals (Kahuna mysticism), everybody has a lower soul—the ‘unihipili, connected to the body and feelings, a medial soul; ‘uhane, related to mentality and thinking; and a superior, immortal ‘aumakua (Wesselman and Kuykendall, 2004, Wesselman, 2008, 2011). Ancient Greek thinkers would definitely ponder upon the tripartite definition of the Kahuna tradition, as in classical Greek thought, the psyche subsumed the emotional and the cognitive functions into one, while the Polynesians perceive these to be functions of two quite different souls.

The composite picture derived from the concepts of the soul in numerous cultures outlines meaningful commonalities and offsets insignificant differences. The results suggest that the singularity defined as “self” by Westerners is actually a cluster, a personal “soul cluster” (Table 1). All aspects of the soul cluster are combined to create a functional self, and all of them are part of the same totality, originating from the same source, yet they exist in very different states of quality. In considering the Hawaiian Kahuna teachings, we find a psychodynamically intriguing interplay between the three soul components, a sort of soul dynamic that has been utilized in treatment concepts and enjoys an extensive multicultural acceptance spanning across space and time. It has been my experience (Frecska) that my psychiatric patients can relate to this tripartite soul division more easily than to the terminology and psychodynamic approach of classical psychoanalysis.

The indigenous peoples understand that the harmony between the components of the self (i.e., the soul forms) is essential for physical and mental health. If the relationship between them is well-balanced and the unity of the three soul components is maintained, then health persists. In other instances where there is disharmony within and between them, healing intervention is necessary.

In the following, we plan to cast light upon the benefits of this perception that are not quite present in Western teachings and practice. Conversely, the traditions of the indigenous cultures can provide this to us if we are open to them. Concretely, as it is expressed in the Kahuna protocol, every soul form can act both independently—in different roles according to their special attributes as well as in special intra- and transpersonal dynamics. Longterm or even complete and final healing may be based on the practical use of this recognition.

Table 1: The Various Presentations of the Tripartite “Soul Cluster”

As mentioned above, the Hawaiian expression ‘aumakua refers to the supreme, immortal aspect of the self and can be translated as “utterly trustworthy ancestral spirit,” or as “the spirit that hovers over me.” In Western teachings, this component of the self appears as the “overself,” the “higher self,” the “divine me,” the “angelic self,” the “transpersonal witness,” the “god self,” and the like. Symbolic illustrations of it in the West depict it typically as a benevolent winged creature, a guardian angel. In Polynesia, it is associated with the creator deity Kane or Tane, and is depicted by an upright stone monolith. Following Wesselman and Kuykendall (2004) and Wesselman (2011), we call it Oversoul, which can be conceptualized as our personal share of the all-encompassing Holy Spirit, or as some call it “the Human Spirit.” Originally, it was Ralph Waldo Emerson who coined the word Oversoul while a divinity student at Harvard University.

The visitation of something magnificent, benevolent, and divine is a frequent subjective experience during mystical altered ASCs, either occurring spontaneously or induced by transpersonal techniques. Those who are less familiar with direct transcendent experiences may interpret this presence as a divine visitation of an angelic greeting or even as a manifestation of the Almighty father-God, and we must always observe that such visitations cannot be ruled out. However such a transpersonal connection is interpreted, one can observe a tendency for the mystical presence to be perceived as being outside the subject's self, although it most likely may be the manifestation of one's own Oversoul. Such a claim must be validated by the words most likely, as—paradoxically—similar interpretations tend to be more accurate when they are less categorizing (i.e., not the “either–or” kind).

In the Polynesian Kahuna tradition (Wesselman and Kuykendall, 2004; Wesselman, 2008, 2011), our Oversoul is observed to be in permanent connection with us in every moment of our lives, both waking and sleeping, whether we are aware of it or not. This connection appears to be surprisingly easy to manifest or activate, and those who practice meditation have a greater ongoing access than those who do not. As part of our soul matrix, the Oversoul monitors all our deeds and thoughts, actions and reactions, emotions and relationships, revealing that privacy is truly an illusion. This self-aspect is passive but not dispassionate toward us, silently feeling concern for our wrong decisions and silently rejoicing upon our successful choices. The Oversoul is a silent observer, as the responsibility for decision making belongs to another self-aspect, the mental-soul or egoic self. This reveals that for most of our lives, our Oversoul does not interfere with our mundane affairs, and neither does it dictate what to do—it respects the right of free choice. However, its protection and guidance can be asked for and invoked. Without such a request, it is only in the rarest cases—perhaps to avoid an “untimely end”—when such an “angelic intervention” or miraculous avoidance experience may happen.

As our wise spirit teacher, our Oversoul is also the source of our inspiration and intuition. It may send us dreams and visions in which it may appear in the image of a spiritual teacher or other wise being, depending on the person's culture, belief systems, and mythical world. Cross-cultural examples reveal that people who have been raised in European traditions may have transpersonal experiences of discarnate entities known in Polynesian or Mesoamerican civilizations. In a relaxed meditative state of perfect calmness and inner peace, such connections can be achieved . . . and then, upon recalling a certain problem, an answer to the dilemma may suddenly appear within the meditator's conscious awareness revealing that the Oversoul is passive only for the passive person. Through personal divination, it may serve as a source of information, and this service can be cultivated with practice.

The Kahuna tradition reveals that the ‘aumakua, the Oversoul, is also our personal creator: the primordial source of our self. At birth it divides itself, sending in a seed of its light that takes up residence within a new body for a new life with the first breath, revealing the breath to be the vehicle of transfer. As our “divine source,” it projects a hologram of its immortal soulcharacter into the newborn, including all its cosmic information content. Similar to many other cosmogenic myths, the Kahuna tradition emphasizes that our personal creator is not a monotheistic off-planet father god, but rather our own divine and immortal part of our self.

All individual Oversouls create a holographic field—the spirit of humankind, termed ka po'e ‘Aumakua (Wesselman and Kuykendall, 2004). As the Oversoul resides outside space and time (i.e., it is nonlocal), the result of this summation is the cumulative (past + present + future) experience and wisdom of our species Homo sapiens. This database corresponds to the “collective unconscious” in Carl Jung's terminology. In Kahuna thought, it is an inexhaustible resource of information, which has been and is being tapped by mystical philosophers and shamanic healers, and which is theoretically accessible to all of us, all the time. Connection with it is often realized during rituals and ceremonies, and in integrative forms of ASCs, with the body-soul being the mediatory agent between our mental-soul and our Oversoul.

Upon its arrival in the biological medium, the nonlocal Oversoul seed must achieve a successful relationship with another soul already in residence: the body-soul sourced into us from our mother and father. The usage of the terms local and nonlocal is essential for us, as they serve as the basis for a rationalizing approach that will be explicated. The body-soul approximates what psychoanalysis calls the “personal unconscious.” In the Kahuna tradition, this self or soul aspect is the source of all our emotions and feelings and is in charge of the entire operation of the physical body, including its repair and restoration. Next to the energetic matrix of the body-soul and that of our own Oversoul, the third soul form, the mental or egoic soul, takes form in response to life as we live it and is shaped by our life events.

According to the Kahuna thought, the body-soul, being energetic in nature, serves as the location of our personal memory storage, and so it is this soul that may recall all personal events upon request by the mental-soul. It is the database of all instinctual and learned behavior and thus serves as our personal operating system and inner hard drive.

The body-soul communicates to the other soul components, the mental as well as the spiritual, by reacting to our life events with emotional responses, expressing what it likes or dislikes. The body-soul does not lie; it expresses itself without inhibitions in the language of emotions, revealing exactly how it feels about a family member, a friend, a job, or a life opportunity. As the interface between our inner and outer worlds, it vividly monitors both the realities in which we act as well as those in which we think, feel, and dream. We could describe it as the mind of the body, which uses our sensory organs to gather information, then forwards the data to our receiving self (mental-soul). This interface function should be emphasized, because the body-soul is both the sender and receiver of all psychic experiences as well as shamanic visions. It is thus the part of our self that makes the spiritual world accessible, according to Kahuna teaching and practice. The inner portal, through which we may make contact with our spiritual guardians and teachers, is located just there, within it. Even the Oversoul part of our self communicates through it to the third soul aspect, the mental-soul or intellect.

The body-soul is the soul of great possibilities. It is at one and the same time material and immaterial, bound by matter and yet free. When Wilhelm Wundt (1920) combined the breath-soul with the idea of the free-soul, he did that on good grounds as both are unsubstantial and unstable. From a psychological viewpoint, the conception of the free-soul, Oversoul, is identical with the memory image of the dead person projected back into the supernatural reality—the airy, ethereal shape of the deceased like a condensation of human breath. The Oversoul and the body-soul thus have qualifications favoring a meeting and merging.

The body-soul—although not by logical abstraction—is able to reason. It provides us with conclusions based on immediate experience. It remembers everything that succeeds or that which causes pain and damage. It is programmed in such a way that induces such behavioral output that helps survival. The body-soul is a fundamental driving force toward our growth, upon acquiring new skills that help us to grow, increase, and become more than we were.

As mentioned above, the body-soul is also our inner healer, programmed to repair our bodies. It restores us based on our genetic as well as our energetic inheritance, and as such, it works with the interactive field of our body components. According to Kahuna thought, these two sources—genetic and energetic—are essential in the healing function because the body-soul is not creative; it is not able to invent and does not draw a plan, but it follows the genetic and energetic blueprint around and with which the body was formed. It is not a leader, but it executes commands as a good subordinate, and it functions at its best when getting unambiguous directives from the mental-soul—from the soul form (self aspect) that is named ego in the West.

Next to the Oversoul and body-soul, the third aspect of our self is the mental-soul, which takes form in the process of our reactions to life events. Well known to the West, this is the intellectual part of the “I” that thinks, analyzes information, integrates, adjudges, assigns meaning to, and functions as our chief executive. It is the source of our rational mind and intentions, and the realizer of our creative inspirations. The mental-soul conceptualizes new ideas, thought forms, and goals, and then aspires to reach them. However, as we have mentioned earlier, the source of this inspiration is the Oversoul, which is accessible to the mental-soul via the interface of the body-soul. In other words, the mental-soul is our intellectual, rational, creative, coping apparatus—our inner director. It is the side of our self that is continuously changing on the basis of our experiences and collected knowledge. The mental-soul is also the bearer of our belief systems that it holds to be true, those same convictions that underlie how well it directs. If the mental-soul faces a challenge that it deems uncontrollable, then it may become inefficient. For example, if one accepts that his or her illness is incurable (and this often happens by external influence, like a medical opinion), then the mental-soul may surrender to the illness.

In Kahuna teaching, a connection exists between feelings and emotions generated by the body-soul and the belief systems held by the egoic self, and long before Aaron Beck, the Kahunas assumed that the former depend on the latter. They understood that feelings inform the mental-soul about which belief is currently the operative one, and that the body-soul expresses its opinion about the dominating schema in the form of feelings. The mental-soul then has a choice, whether to accept the subconscious message and to act accordingly, or to discard it by declaring as invalid. Mental and physical health presumes a good working relationship between the mental-soul and the body-soul. Indeed, this is not a democratic relationship; the mental-soul is the master, and the body-soul is the servant. As the superior agent of our coping mechanism, the mental-soul directs the activity of the bodysoul, which serves as its executer. However, this dominance is maintained only in the ordinary state of consciousness, when orientation to the outer world is adaptive and the main daily task is coping. Meditative, contemplative, and ritual techniques may break the mental edges and the dominance of the ego, and may evoke a state in which the mental-soul introspectively receives signals coming from the Oversoul, crossing the bridge (or interface) of the body-soul.

The mental-soul has a rather heterogeneous and sometimes obscure nature. In its “pure” form, it constitutes a hypostasis of the stream of consciousness, the center for thinking and willing—the intentional mind in a broad sense. But at the same time, the mental-soul manifests certain peculiar features, which makes it clear that it is not just an expression of the individual's own personality but also functions as a being within the individual which endows him with thought, will, and so on. This “soul of consciousness” is motivated by order (this influence is coming from the Superego in Freudian theory); the body-soul by comparison is motivated by desire or pleasure (a characteristic of the Freudian Id). The conscious content of the ego may thus manifest certain independence—especially when neurotic persons are found to be in conflict with compulsive notions, acts, phobias, etc., sourced by the body-soul. This peculiarity of the mental-soul explains why we find it now split into several potencies, now taking up an exaggeratedly independent, at times superior, attitude toward its owner. On the other hand, most addictive or impulsive behaviors are expressions of the body-soul that may assume dominance over a poorly developed mental-soul.

The Polynesian teachings draw upon the dynamism and essence of much the same trinity that accompanies the history of many other cultures, including the significant tradition in Western thinking. It is indeed thought provoking for us that at the dawn of European philosophy, expressed through Pythagoras and Plato, the transcultural similarity is demonstrable. Pythagoras believed in the immortality and transmigration of the soul. Plato understood that the soul differs from the body and that it can exist separately as pure thinking, but his thoughts do not reflect whether the soul can or cannot survive death (Janaway, 1995). Plato argues that the human soul has three parts: Logos (an intellective, rational part), Thymos (a spirited part, having to do with emotion and will), and Eros (an appetitive part, having to do with drives and basic impulses). Each of us has two mortal soul parts—appetite and spirit—plus one, the intellect, which is immortal (Sedley, 2009).

Aristotle avoids addressing the principle of immortality. He thinks of the soul as a substance, the form of a potentially living natural body, which accomplishes and consummates the possibility of supplying bodily functions. Aristotle attempts to explain life processes with the soul; he distinguishes three soul parts, according to three assumed life processes: nutrition–reproduction, sensation, and cognition. In his case, the unity of the self is already far away. Aristotle did not consider the soul in its entirety as a separate, ghostly occupant of the body (just as we cannot separate the activity of cutting from the knife). As the soul, in Aristotle's view, is an actuality of a living body, it cannot be immortal. Perhaps it was the influence of his physician father that caused the narrowing of his soul concept to biological and psychological relations. Following Aristotle's footsteps, Western scientific thinking was influenced accordingly, until it reached the point where the notion of the soul had eventually become completely disqualified. We take it that, avoiding the metaphysical, “direct-intuitive” experience (Strassman et al., 2007) provided by integrative forms of ASCs (like the shamanic state), the idea of immortal soul has gradually lost ground in Western philosophy.

Yet Aristotle also described a quality of being that is closely allied with the perception of the Oversoul. He called it the entelechy—that which is already realized as opposed to the energia (the energy body) that carries the life force that motivates and orients an organism toward self-fulfillment. The entelechy was understood in classical philosophy as a fullness of actualization that requires ongoing process and effort in order to continue to grow and thus exist, perpetually becoming itself . . . a good description of the Oversoul.

Plotinus of Lycopolis (205–270 CE) presents arguments for the tripartition-cum-trilocation of the soul (Plotinus, 1991) advanced by Plato in Timaeus (2001). His version is marked by a clear spatial separation between the three parts of the soul: reason in the brain, will in the heart, and desire in the liver. Plotinus refers to the ideas presented by Galen of Pergamon in his work On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato (Galen, 1978/1980). At the same time, he takes stance for the unity and incorporeality of the soul. From Galen's perspective, the parts of the soul are not located in the three bodily organs in an ordinary sense—only their activity takes place there.

In Islam, the human soul is also split into three parts: the Qalb (heart), the Ruh (blood), and the Nafs (passion of the soul). In the words of Ibrahim Haqqi of Erzurum: the heart is the home of God. Qalb enables the individual to perceive God as the All-Helping and All-Maintaining. Interestingly, the immortal Oversoul seed is also felt by the Kahunas to reside in the heart.

The Zohar, a classic work of Jewish mysticism, separates three soul parts as neshamah, ruach, and nephesh. They are characterized in this way (Von Rad, 1965): Neshamah is the higher soul, or Oversoul. It allows man to have awareness of the existence and to feel the presence of God. It is the bearer of intellect and provides us the gift of immortality. This part of the soul is implanted at birth. After death, neshamah returns to the source. Ruach is the middle soul. It carries the moral virtues and gives humans the ability to distinguish between good and evil. Ruach corresponds to the ego, to the mental-soul in our terminology. Nephesh is a living mortal essence: it feels pain, hunger, and emotions, and most importantly, it eventually dies. It is the source of one's physical and psychological nature. The last two elements of the soul are not given at birth but are continuously created over time; their maturation depends on the beliefs and deeds of the person.

“Man is a bundle of relations, a knot of roots, whose flower and fruitage is the world.”

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1841/1979, p. 20)

One could raise a justified doubt about the fundamental basis for using the notion of the soul at all. As an answer: the Kahuna can “psychodynamize” and elucidate by using the three soul forms, and can even build a healing praxis on this basis. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that the thing must be more than just a hollow metaphor (even the phlogiston theory was capable of explaining certain phenomena). The Kahunas knew that metaphors work powerfully because the body-soul takes everything literally and does not distinguish between reality and illusion. It perceives both as real.

Rational content can be given to a metaphor by deducing or transferring it into other metaphors that have been approved in other fields of science. If we discern a premise which is extremely reductionist and which constricts our aspects, then questioning the given starting point can take us forward on the cognitive path. What we are questioning here is that our self, our human essence, and all of our experiences would be reducible to the operation of one and only one network: the neuroaxonal network. If we accept that other networks—operating by other and different types of information processing strategies—may also contribute to our human essence, then we may reasonably address many concepts that so far have been excluded from the reference framework of rational thinking.

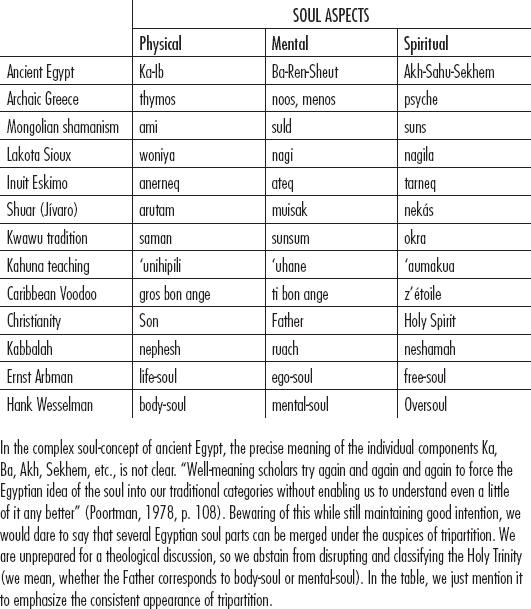

Table 2 summarizes the levels of organization supposedly involved in generation of the conscious experience. Since the topic of consciousness is mostly ignored by mainstream neuroscience, it is difficult to determine the opinion of prominent brain researchers. Despite some positive trends in other disciplines (for example, physics), orthodox neuroscientists avoid the issue, and unorthodox ones use the politically correct term awareness when preparing their grant proposals. Nevertheless, with the exception of the very top level and one at the very bottom, most neuroscientists would not disagree with the assumption that all these levels represented in Table 2 are involved in the process.

To avoid the trap of radical reductionism, one must assume that all levels are at work with bidirectional interrelated causative processes (bottom-up and top-down reciprocal interactions). Let us pay attention to the position of the dashed line in Table 2. Illustrating the contemporarily accepted view, it divides levels based upon their assumed causational role in generating the conscious experience.

Table 2: Organizational Levels That Play a Role in the Human Experience

According to the theories on the neural correlates of consciousness, the neuroaxonal system has a pivotal role both in the emergence of conscious experience and in the function of levels above it. In his book, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, Steven Pinker (2003, viii) writes, “Culture is crucial, but culture could not exist without mental faculties that allow humans to create and learn culture to begin with.” The effect of culture in shaping brain structure and neuroaxonal function is also permitted. In cogent and convincing writing, Bruce Wexler (2006) argues that our brain does not merely dictate how we respond to changes in the environment but is also itself shaped through interaction with the social world. Briefly, social relations, even culture and ideology, affect neurobiology.

This means that above the dashed line bottom-up and top-down interactions are at work, and every level is supposed to have an active role. This is not the case below it: the assumption here is that subcellular levels are passive, subserving higher levels by permitting, but not shaping, their function. Here the causation operates only from bottom-up, but the role of top-down effects is not believed to operate at this level in mainstream neuroscientific thinking. Above the horizontal line, there is a well-balanced “cooperative hierarchy”; below it, “oligarchy” is the rule. Of course, this is an arbitrary delineation with broken symmetry. It lacks an explanation about why only the upper half has active and reciprocal interactions. Perhaps it would be more consequent and congruent to suppose that subcellular levels also have an active role in the creation of the human experience and that they add something to the self, which is a characteristic of their level. Considering their size, this characteristic could be their relation with quantum reality.

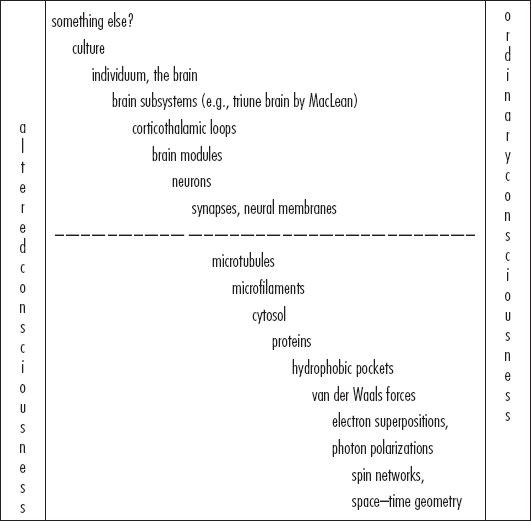

So what is this quantum characteristic that subcellular parts can enrich the human experience with? We assume that it is “nonlocality” (more specifically “signal nonlocality”), which is an important property of the quantum processes. In brief, nonlocality means that if two elementary particles were once part of the same quantum system, then they remain in immediate interaction, regardless of their position in space and time. If the quantum state of one particle changes, then the state of the other quantum entangled particle will also change simultaneously—no matter how far apart they are from each other in space and time. “Signal nonlocality”—a new fertile term in 21st-century physics—means that a change in the state of a system induces an immediate change in an interconnected (entangled) system. A subcellular network (perhaps the lipoprotein membrane complex) might enable the brain to receive “nonlocal” information and to transmit it toward the neuroaxonal network (Figure 1). A tentative function of subcellular components by forming a “quantum array antenna” of the brain is discussed in our book (Strassman et al., 2007). A biological model of information processing is proposed there, in which subcellular, cytoskeletal networks serve as the basis for quantum computation and represent a medium of quantum holography.

The connection to quantum reality can be mediated by a subcellular network that presumably covers the whole body and represents a space- and time-independent holographic image of the Universe inside the body by “nonlocal” connections, in other words, by quantum correlations (Figure 1). “Nonlocal” information about the physical Universe provides the missing link between objective science and subjective experience, including the mystical experience. Based on the principle of “nonlocality” and with the “quantum array antenna” of subcellular networks, the brain (and the full body) is in resonance with the whole Universe. A faint hologram of the Cosmos emerges inside the body, and regardless how pale it is, it is able to present wholeness and can elucidate teachings like: “The kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21, in Greek, entos hymon), or “Look inside, you are Buddha” (Humphreys, 1987). The perennial wisdom of “As above, so below” (or: “As within, so without”) obtains a fresh perspective and there is hope for the integration of similar teachings into Western rational thinking. Subcellular matrix can be the mediator of the Jungian “collective unconscious,” and cytoskeletal quantum holography can explain a very common but obscure phenomenon known as “intuition.”

Figure 1: The hierarchy and speculative interaction of networks related to human experiences.

We represent a radical idea that the world of well-integrated ASCs is related to quantum processes, while the reality of ordinary consciousness belongs—beyond doubt—to classical physics. Their boundary is probably not sharp at all; ordinary conscious experience can be affected by quantum processes as well (in some cases of intuition), and many features of the experiential world of altered states can also be deduced from classical physics. We see a seamless continuum with phase transitions from the classical-physics based neuronal brain functions all the way to the quantum-physics based subneuronal “direct intuitive” information processing.

While the “nonlocal” connections are permanent, in ordinary states of consciousness, there is only a very limited and mostly unconscious shift of the “nonlocal” information into the neuroaxonal system—since the coping apparatus, the “survival machine,” is mostly focused on the more reliable “local” signals coming from the perceptual organs—so only a little or none can get into the focus of attention of the “I.” In integrative forms of ASCs (e.g., meditation and contemplation), coping, planning, and task-solving functions are put into the background along with the agent (ego) bearing those functions. Thus, a chance appears for fragments of “nonlocal” information—present already in subcellular networks—to be projected and transferred into the neuroaxonal network and to be experienced also by the ego. This outlined hologram can be a stage for out-of-body experiences: consciousness does not leave the body, but its introspective attention sweeps the “matrix,” i.e., the field of “nonlocal” correlations mediated by the subcellular network.

In biological systems, everything that involves a transfer of energy (i.e., of mass—by the Theory of Special Relativity), leads inevitably to a change in space–time geometry (by the Theory of General Relativity), and shows up by making imprints in complex nonbiological networks (spin network—Penrose, 1971.) Where there is a complex network, there must be a function, and an agent can be assigned to that function. Thus, the mental-soul (ego) can be assigned to the neuroaxonal system, the body-soul to the subcellular networks (lipoprotein membrane complex), and the Oversoul to a nonbiological, basically physical network (spin network, space–time geometry). The referred native peoples and antique philosophers (namely Pythagoras, Plato, and Galen) may have intuitively sensed the presence of these network functions representing “agents” in their soul concepts. Based on the association above, a careful watch on Figure 1 reveals that the presented model reflects quite accurately the dynamics of the Kahuna soul forms: the Oversoul (‘aumakua)—the agent of the nonbiological network—is in a permanent connection with us in every moment of our lives; the body-soul (‘unihipili)—the agent of the subcellular matrix—is the bridge between the Oversoul and the mental-soul (‘uhane)—the agent of the neuroaxonal system—and serves as an inner portal to receive transpersonal information. Moreover, the model shows an analogy with the Shuar concept in that the arutam wakanl (which corresponds to the body-soul in Table 1) is the bearer of visions. As we have earlier mentioned, biological metabolism, conformation change of molecules can affect space–time geometry. By the Kahuna teachings, this can also hold in reverse: see above the detailed “download” of the Oversoul at the formation of the body-soul.

There is another benefit of the presented model—it may explain away the confusion in the classification of soul components: Soul dualism results from combining the biological network agents (life-soul and ego-soul) in contrast to the nonbiological one (free-soul). The tripartite soul concept emphasizes more their unique role and sets the foundation of “soul-dynamic psychotherapy.”

Several arguments can be raised against the outlined model questioning the special role of each presented network. Within the matrix of the lipoprotein membranes, is it the microtrabecular lattice that makes humans (and other cellular organisms) capable of carrying an albeit faint hologram of the Universe, or is it something else? Is it—alternatively—the microtubular cytoskeleton, which is the proposed medium of quantum computation in the Penrose-Hameroff model (Penrose, 1996)? At the bottom rung, others would not put space–time geometry—an already outdated concept, some experts believe—but entangled quantum holograms in the universal (“Akashic”) field (Laszlo, 2009). Ervin Laszlo argues (personal communication) that space-time is itself a manifestation of the field—there is neither space nor time prior to the quanta that arise in the topological field. Moreover, what functions as the source of information on that fundamental level is not “geometry”—he goes on—but the “nonlocal” network of quantum holograms: the informational structure of the field. Nevertheless, the strength of our concept is not tied to the successful proposal of one specific network, but to the argumentation that there must be “nets” other than the neuroaxonal for shaping human experiences, and there must be at least three, with one of them being nonbiological.

We consider as the miracle of nature not only that the three soul forms can have a material basis—although it can already be unacceptable for many. Their interaction, which catapults the human experience to the infinite, fascinates us more, and so does the fact that a rational explanation can be created even for this relation-dynamics—although by stretching academic frames. These and similar thoughts are explicated in detail in the book Inner Paths to Outer Space (Strassman et al., 2007) for readers who are open to interdisciplinary trespasses. As we are not sure about the same attitude at present, we have shortened our discussion—which may sound cumbersome and far-fetched for many—as much as we could. On the other hand, we cannot see any other way to authentically interpret these and similar teachings. To ignore or to belittle them is another possible way—but it does not lead to progress. Evidently, these are concepts and theories that need to be discussed and developed.

1. Address correspondence to Ede Frecska, Department of Psychiatry, University of Debrecen, Nagyerdei krt. 98., 4012 Debrecen, Hungary. E-mail: efrecska@hotmail.com

2. Instead of God we would prefer the use of Great Spirit, which is more consistent with the tribal, shamanistic worldview.

3. Coined by following the triune brain model of Paul MacLean (1990).

Arbman, E. 1926/1927. Untersuchungen zur primitiven Seelenvorstellungen mit besonderer Rucksicht auf Indien, Part 1 and 2. Le Monde Oriental 20:85–222 and 21:1–185.

Bartle, P. F. W. 1983. The Universe has three souls: notes on translating Akan culture. Journal of Religion in Africa 14(2):85–114.

Bremmer, J. 1983. The Early Greek Concept of the Soul. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dodds, E. R. 1951. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Emerson, R.W. 1841/1979. The essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Fejos, P. 1943. Ethnography of the Yagua. New York: Viking Fund, Inc.

Frecska, E. and Luna, L. E. 2006. Neuro-ontological interpretation of spiritual experiences. Neuropsychopharmacologia Hungarica 8(3):143–153.

Galen 1978/1980. De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis (On the doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato). In Corpus Medicorum Graecorum, Vol. 4.1.2, Part 1 and 2, Ed. De Lacy, P., 1:65–358 and 2:360–608. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Hall, M. P. 1965. The Soul in Egyptian Metaphysics and the Book of the Dead. Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society

Harrell, S. 1979. The concept of soul in Chinese folk religion. The Journal of Asian Studies 38(3):519–528.

Huffman, C. 2009. Pythagoras. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, Ed. Zalta, E. N. First published on February 23, 2005, Revisioned on November 13, 2009, Retrieved on August 14, 2010 from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pythagoras/.

Hultkrantz, Å. 1953. Conceptions of the Soul Among North American Indians: A Study in Religious Ethnology. Stockholm: Caslon Press.

Humphreys, C. 1987. The Wisdom of Buddhism. London: Curzon Press.

Janaway, C. 1995. Ancient Greek philosophy I: The pre-Socratics and Plato. In Philosophy: A Guide Through the Subject, Ed. Grayling, A. C., 336–397. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kingsley, P. 1999. In the Dark Places of Wisdom. Inverness: The Golden Sufi Center Press.

Kingsley, P. 2003. Reality. Inverness: The Golden Sufi Center Press.

Koepping, K.P. (1983). Adolf Bastian and the Psychic Unity of Mankind: The Foundations of Anthropology in Nineteenth Century Germany. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Laszlo, E. 2009. The Akashic Experience: Science and the Cosmic Memory Field. Rochester: Inner Traditions.

MacLean, P. D. 1990. The Triune Brain in Evolution: Role in Paleocerebral Functions. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Penrose, R. 1971. Angular momentum: An approach to combinational space–time. In Quantum theory and beyond, Ed. Bastin, E. A., 151–180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Penrose, R. 1996. Shadows of the mind: A search for the missing science of consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pinker, S. 2003. The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Plato 2001. Timaeus. Newburyport: Focus Publishing.

Plotinus 1991. Enneads. London: Penguin.

Poortman, J. J. 1978. Vehicles of consciousness: The concept of hylic pluralism. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House.

Purev, O. 2004. Darkhad shamanism. In Shamanism: An encyclopedia of world beliefs, Practices, and Culture, Eds. Walter, M. W. and Fridman, E. J. N., 545–547. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Sarangerel (Stewart, J. A.) 2000. Riding windhorses: A journey into the heart of Mongolian shamanism. Rochester: Destiny Books.

Sedley, D. 2009. Three kinds of Platonic immortality. In Body and soul in ancient philosophy, Eds. Frede, D. and Reis, B., 145–162. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Shirokogoroff, S. M. 1935/1982. Psychomental complex of the Tungus. Original edition, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. Reprint, New York: AMS Press.

Symonds, P. V. 2005. Calling in the soul: Gender and the cycle of life in a Hmong Village. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Strassman, R., Wojtowicz-Praga, S., Luna, E. L., and Frecska, E. 2007. Inner paths to outer space. Rochester: Inner Traditions.

Stutley, M. 2003. Shamanism: A concise introduction. London: Routledge.

Von Rad, G. 1965. Old Testament theology. San Francisco: Harper.

Wesselman, H. and Kuykendall, J. 2004. Spirit medicine: Healing in the sacred realms. Carlsbad: Hay House, Inc.

Wesselman, H. 2008. Hawaiian perspectives on the matrix of the soul. The Journal of Shamanic Practice 1:21–25.

Wesselman, H. (2011, in press). The bowl of light: Ancestral wisdom from a Hawaiian shaman. Boulder: Sounds True.

Wexler, B.E. 2006. Brain and culture: Neurobiology, ideology, and social change. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Wilson, E.O. 1998. Consilience. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Winkelman, M. and Baker J. R. 2008. Supernatural as natural: A biocultural approach to religion. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Wundt, W. 1920. Völkerpsychologie, IV. Band: Mythus und religion, I. Teil. Leipzig: Engelmann.