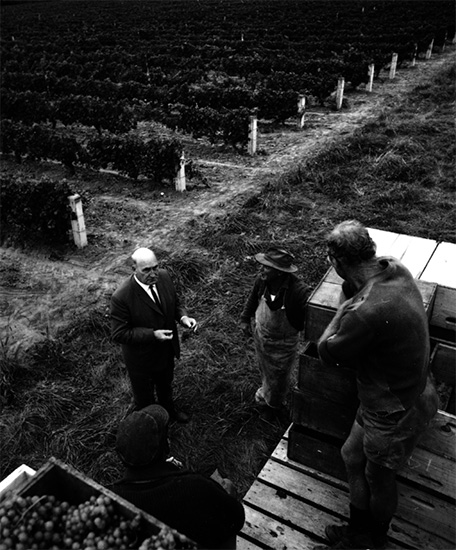

At nineteen, Dudley Russell began terracing land and planting grapes in the Henderson Valley. By 1960, his Western Vineyards was focusing on unfortified wines and vinifera grapes – the industry’s future. Dick Scott Collection, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

2

New Zealand Vines and Wines circa 1960

At the 1958 New Zealand Easter Show, Class 6 of the Wine Section was for an ‘Unfortified White, Hock type, not over 26 per cent proof spirit’. Four medals were awarded from fourteen entrants: McWilliam’s Wines Ltd of Hawke’s Bay won first prize; Josip Babich won second; Western Vineyards won third; and A. A. Corban and Sons won fourth prize.

Of these four firms, only one name persists as a commercial entity today. David, the grandson of Josip, is general manager of Babich Wines and works alongside his father Peter and his uncle Joe at their Henderson Valley winery. McWilliam’s Wines is today represented on the New Zealand landscape only remotely, by the Church Road, Hawke’s Bay winery of the former Montana, now owned by the French company Pernod Ricard New Zealand Ltd. A. A. Corban and Sons (by then trading as Corbans Wines Ltd) was bought by Montana in 2000. Pernod Ricard retains ‘Corbans’ as a brand, and the name also continues to be associated with the wine industry through Alwyn Corban of Ngatarawa Wines and his late uncle Joe who started Corbans Viticulture Ltd in 1979. The vines of Western Vineyards (third prize) are still visible on the landscape of Waitakere but only as a series of swirls on Candia Road about 2 kilometres from the Babich winery. These are the terraces of one of the most elegant vineyards of its time, still sculpted in the yellow Waitemata clays of West Auckland. Its winery is now used for yoga classes.

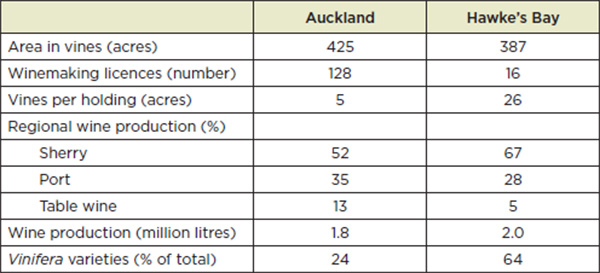

If the people and firms of 1958 are now a faint memory, so too are the dominant wines. Of the 22 classes of wine judged at the 1958 Easter Show, twelve were for fortified wines and ten for unfortified or table wines such as the hock type won by McWilliam’s. Considering the consumption habits of the time, the number of classes for table wine is astounding. In the late 1950s, only 13 per cent of West Auckland winery production was table wine, and among Hawke’s Bay wineries the proportion was just 5 per cent. The remaining 77 per cent of wine produced in West Auckland and the remaining 95 per cent in Hawke’s Bay comprised sherry, port and liqueurs.

Nevertheless, the beginnings of the modern New Zealand wine industry could be seen in faint glimmers at the 1958 show. Dudley Russell of Western Vineyards was one of the people setting the wine trends in the late 1950s and into the 1960s. Table wines (‘unfortified wines’ in the language of the time) made up almost a third of Western Vineyard’s production in 1958 – the only large winery in New Zealand to approach this proportion. Some firms made no table wine. Two neighbours of Western Vineyards also figured in the table wine market. Sixty per cent of Paul Groshek’s production at Muaga wines across Candia Road was unfortified wine and almost 20 per cent at the Josip Babich winery.

In the ‘Commercial Classes’ of table wines, the larger companies were also emerging to establish a preliminary pecking order. For dry table wines, sixteen prizes were available in the four classes: Corbans won eight, McWilliam’s won six, and Babich and Vidal managed one each. In the ‘Hock’ type, Corbans won three of the four prizes – a portent of Alex Corban’s Riverlea Riesling of the next decade. McWilliam’s won ‘Best Wine in Show’ for one of their wines entered in the ‘Claret’ type. Their innovative Bakano and legendary 1965 Cabernet Sauvignon orchestrated by Denis Kasza for Tom McDonald were on the near horizon. Neither Villa Maria nor Montana entered wines in 1958. But in 1961 George Fistonich gave up carpentry to get involved full-time in his father’s wine business at Villa Maria. In the same year, Frank and Mate Yukich contributed $250 each to float Montana Wines and develop their father’s business. The transformation of the New Zealand wine industry loomed.

Geography of vines and wines from mid-century

The results of the Easter Show reveal much of the international and internal geography of the vine and wine around 1960 as well as clues to their future. Wines were named after those of other countries – Hock, Chablis, Claret, Burgundy, Sherry, Port, Vermouth, Sauterne. At least in the case of the ‘Sherry’ type, and especially dry sherry, the grapes were sometimes Palomino, the variety from which the genuine sherry from Jerez de la Frontera is made. By contrast, the ‘Hock’ type did not see many kilograms of Riesling nor the ‘Chablis’ type many pounds of Chardonnay. Riesling was not listed in the official data of the time, although Riesling-Sylvaner (Müller Thurgau) was. Ministry of Agriculture data for 1960 listed 6.5 acres of Pinot Chardonnay (as it was then called in New Zealand) compared with 107 acres of the hybrid Baco 22A.

New Zealand wines circa 1960: 38% proof Blackberry Nip from Glenvale Wines in Bayview, Hawke’s Bay; Sweet Sherry from Ballins Industries; and Spence’s Sparkleburg. Dick Scott Collection, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

A similar pattern was revealed in the reds. The dominance of Anglo settlers and thinking is evident in naming the two red wine classes ‘Claret’ type and ‘Burgundy’. But just 16 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon, 14 of Malbec and 6.5 of Merlot – the Claret or Bordeaux varieties – are recorded in 1960, predominantly in Hawke’s Bay. At the time, Albany Surprise (the New Zealand variant of the American table grape Concord) was the most common red variety with 98 acres being used for wine. Paul Groshek named his popular, dry red table wine – Albonez – after it. The hybrid Seibel 5455 is second among the reds with 68 acres. Both of these varieties were undoubtedly present in some of the wines of the red wine classes named ‘Claret’ type and ‘Burgundy’. In fact, many red table wines were made entirely from these hybrid varieties.

While the New Zealand table wines judged at the 1958 Easter Show drew on European precedents for the names, the grapes grown had drifted far from the classical varieties that produced the major wines of France, Spain, or Italy. A few examples of classical varieties continued to be cultivated, such as the Spanish grape Palomino, but these also found their way into the popular sweet and fortified sherries and ports of the day. This pattern in New Zealand’s grape production was shaped by the two major wine regions of the time – West Auckland and Hawke’s Bay. Contrasts between these two winegrowing regions are not so obvious from the results of the awards, but they were considerable.

Auckland

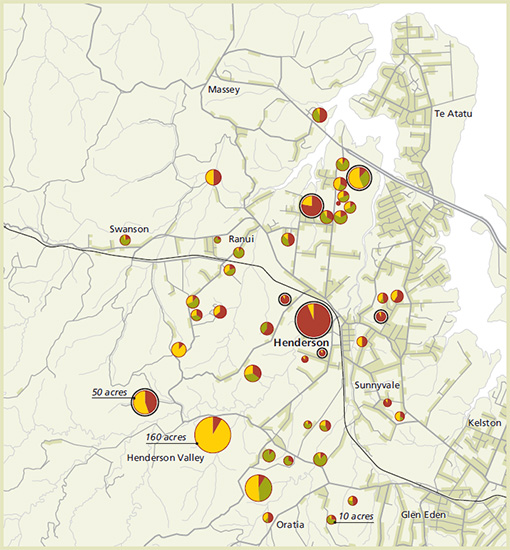

West Auckland vineyards and wineries in 1960 were small, mixed holdings (Figure 2.1). All but a few of them combined growing grapes with orcharding, and most ran some livestock on the rest of their property. A few still practised market gardening. Over 90 per cent were owned by people who at the time were called Yugoslavs, after their country of origin, but colloquially known as ‘Dallies’ because many came from the Dalmatian coast of Croatia. They were family enterprises sometimes involving two families and more than one generation. The average size of vineyards in Henderson-Oratia was 5 acres (about 2 hectares) but much smaller if the three largest vineyards and wineries – Corbans (130 acres), Averill’s (35 acres, later Penfolds) and Western Vineyards (34 acres) – all owned by non-Croats – were omitted.

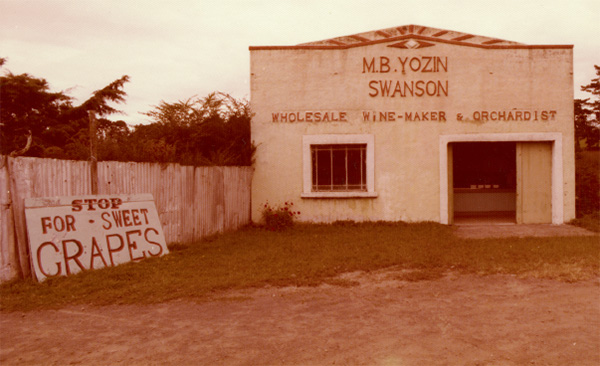

In Auckland, properties were small, wineries were modest, and the proprietors were often grape growers, orchardists, winemakers and shopkeepers on the same day. Yozin’s building still stands on Swanson Road, no longer used and surrounded by suburban homes. Dick Scott Collection, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

On average, 70 per cent of the wine made on these Croatian holdings was sold directly to the public, mainly from the cellar but sometimes by door-to-door hawking in Auckland and other regions. Cellars were small, unpretentious buildings adjoining the family home. Brick and concrete blocks were favoured building materials. Most had a small, adjoining distillery for turning grape residues into alcohol for fortifying their ports, sherries and liqueurs. Co-operative ‘stills’ were illegal. The spectre of prohibition still hovered, although weakened by the experiences of the Second World War. A visit to one of these wineries – say that of Mate and Melba Brajkovich in Kumeu, or George Mazuran or Peter Fredatovich in Lincoln Road, was as friendly and welcoming as at any family holding in France or Italy. At this stage of their evolution, only the wine was different. From about 1960, the second, New Zealand-born generation of Dallies were beginning to work on the family holdings. They brought change.

Figure 2.1 Vineyards (red), orchards (green), and other land (yellow) on mixed horticultural holdings in Henderson-Oratia, West Auckland, 1960, where circle size corresponds to the size of a holding. The seven properties with a second circle were owned by families of non-Croatian descent.

These West Auckland enterprises were on the doorstep of a city that was beginning to expand rapidly. The northwestern motorway opened in 1958. Roadworks to double its capacity and to widen its bridges began immediately. Although it was not obvious at the time, those Dalmatian families who owned larger parcels of land, or continued to acquire land, would become rich in assets as the land was zoned residential, industrial, or commercial. For a long period they were sufficiently politically active and valued by the community that their property taxes were calculated as if they were in a rural area. That wealth helped drive the growth of the New Zealand wine industry.

Hawke’s Bay

The Hawke’s Bay wine industry was so different it could have been in another country, perhaps Australia. Four enterprises – McWilliam’s Wines Ltd, McDonald’s Wines, Glenvale Wines and Vidal – dominated winegrowing in Hawke’s Bay. Each made over 50,000 gallons (227,500 litres) of wine annually. In Henderson, Corbans (85,000 gallons) was the only winery with a similar level of production. In 1960 the four Hawke’s Bay wineries were responsible for 86 per cent of the region’s production. Using the categories of New Zealand Winegrowers in the twenty-first century, all of these wineries would be in Category 2 – over 200,000 litres. Only two other wineries in Hawke’s Bay – Mission Vineyards and Te Mata Vineyards Ltd – produced over 5000 gallons of wine annually in 1960.

The marketing of Hawke’s Bay wine was quite different from that of the West Auckland family businesses. The region’s large enterprises sold almost all of their wine through wholesale liquor outlets, hotels, or wine shops. McWilliam’s Wines, when merged with McDonald’s in 1962 and managed by Tom McDonald, was producing over half of the Hawke’s Bay wine. The two main New Zealand breweries and wholesalers of wines and spirits, New Zealand Breweries and Dominion Breweries, were substantial shareholders in McWilliam’s. The sales by region of McDonald’s Wines just before merger shows clearly the close relationships it had with the established retail outlets of the South Island, where some of the powerful importers and wholesalers of wine and liquor were dominant. Only 11 per cent of its wine was sold in Auckland and 14 per cent in Wellington compared with almost 50 per cent in the South Island and almost 18 per cent locally in Hawke’s Bay.

None of the Hawke’s Bay vineyards in 1960 were far from the coast. They formed a discontinuous belt from Bay View and the Esk Valley in the north, where Glenvale Wines of the Bird family was located, to Havelock North in the south. In between, one of Vidal’s substantial vineyards was right on the coast at Te Awanga, and Mission Vineyards and the McDonald winery at Greenmeadows west of Napier formed another node. The headquarters and winery of Vidal was in Hastings and McWilliam’s winery was in Napier, but both firms had vineyards in several localities.

Grapes of European origin (Vitis vinifera) were much more important in Hawke’s Bay where they represented 64 per cent of the total area in vines. In the Auckland region they represented only 24 per cent. This dominance of vinifera varieties is partly explained by Hawke’s Bay being free of the pest Phylloxera vastatrix at the time. Vines in North America, including Vitis labrusca, are resistant to this disease and hybrids of American vines and vinifera vines are also resistant to varying degrees. Indeed, the American vines were originally imported into France for breeding as French scientists experimented by crossing them with vinifera varieties. The resistance to disease of these crosses partly explains their importance in Auckland where over 75 per cent of the vines were hybrids. The hybrids and labrusca varieties are more robust in heavier soils and able to resist various fungus diseases in regions where rainfall and humidity are higher. Heavy soils and high humidity dominated those parts of Auckland where vines were grown at the time.

‘He rules by force of personality,’ noted Cooks Wine Bulletin in April 1971. At McWilliam’s Wines, Tom McDonald led a team that included Denis Kasza and Peter Hubscher to make some excellent Cabernet Sauvignons. But by the 1970s, Hubscher came to view McWilliam’s as ‘a sherry factory . . . based on water and sugar’. Marti Friedlander, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

Dalmatians who settled in West Auckland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did not choose it for the suitability of its natural environment for vines, orchards and market gardens, but rather for the opportunities that the nearby urban area offered as a market and for employment. Moreover, its heavy, largely clay soils made the land cheap. These Dalmatians had plenty of experience with clay and other difficult soils from their gumdigging in Northland and other parts of the country. Persistent hard work in clearing the land and working the soils of Henderson-Oratia made it possible to grow grapes and fruit trees (especially apples) and vegetables for the Auckland market. Chain migration to the same locality from within New Zealand and internationally brought increasing numbers of Dalmatian settlers to Henderson-Oratia and later to Kumeu-Huapai.

Table 2.1 Vineyards and wineries in Auckland and Hawke’s Bay, 1960

Hawke’s Bay, with its much lower precipitation (under 800 mm compared with over 1400 mm in West Auckland), lower humidity and higher sunshine hours, is a more suitable natural environment for growing grapes to make table wine. In addition, its soils are more varied and versatile. They include loams, clays and river-deposited gravels. These natural advantages of Hawke’s Bay became clear from the 1960s when table wines became more important. But the heavier soils and higher precipitation in West Auckland have not precluded excellent wines being produced there, provided the standard of vineyard management and vinification is high. Enterprises such as Kumeu River Wines have persistently demonstrated these capacities. Moreover, West Auckland Dallies were to continue to have a major role to play in the evolution and resilience of the New Zealand wine industry.

In addition to the concentrations of viticulture in West Auckland and Hawke’s Bay, two other smaller nodes are worth noting – Te Kauwhata and Gisborne. They had different origins and different local economies in the 1950s. The establishment of New Zealand’s Viticultural Research Station at Te Kauwhata in 1902, with Italian-educated viticulturist Romeo Bragato heading it, had stimulated the area’s viticulture and winemaking, but also orcharding and other smallholdings. By 1960, Te Kauwhata was growing primarily table grapes (Albany Surprise) and apples, although some wine was being made in the locality. This research station remained active until the middle decades of the twentieth century and Te Kauwhata later received a temporary stimulus when Cooks Wines, founded by the Auckland entrepreneur David Lucas, planted vines there in 1969 before establishing a modern winery in the 1970s.

In the early days of the New Zealand industry, bushy vines produced grapes in great quantity. Dick Scott Collection, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

Gisborne had a much smaller area in vines in 1960, with the Wohnsiedlers of German origin growing 20 hectares of grapes and making wine there. Wattie’s established a vegetable processing plant on the Poverty Bay flats in the 1950s which stimulated horticulture more generally, and many smallholders on the Gisborne Plain became skilled in growing fruit, vegetables and other crops. Gisborne was to play a key role in the initial establishment of modern New Zealand winegrowing in the 1960s, 1970s and into the 1980s.

A transforming moment

The modern New Zealand wine industry developed out of the assortment of wines and vines established in a few regions by about 1960. In Auckland, it was also driven by a group of enthusiasts who saw the development of wine in New Zealand as one part of changing the wider culture. Its spiritual home was Paul Groshek’s Muaga Vineyards in Candia Road, Henderson, where conversation flowed freely, stimulated by Groshek’s wide interests and lubricated by his simple, unadulterated table wine – even on Sundays. The writer Rex Fairburn’s polemical broadsheet Crisis in the Wine Industry, published by Pelorus Press in 1948 and reprinted in 1949, systematised some of the conversations from these symposia at Groshek’s winery.

New Zealand is probably the only country in the world with a wine-growing climate that has failed to give strong and consistent support to its wine industry. This has been due partly to the restrictive effect of the activities of certain vested interests (some of them belonging to ‘the trade’ and some opposed to it), and partly to lack of public knowledge and appreciation of the value of wine as a staple article of diet.

Is there in New Zealand politics a man with sufficient vision to see the possibilities – economic, social and cultural – that are latent in the wine industry of this country and in the unused acres of second-class land that could be adding greatly to the wealth of the Dominion?

In the late 1950s, government action followed. From 1938 under Import Control Regulations the imports of wine and spirits were halved for several years. This reduction in supply of spirits and wine (coming mainly from Australia) coincided with increased demand for alcohol during the Second World War, partly because of the large number of American troops stationed in New Zealand. Local winegrowers responded by increasing production. But their favourable trading conditions were short-lived. Imports increased; and by 1948, overproduction in New Zealand wine was assumed to have arrived. A Royal Commission on Licensing in 1946 considered all alcohols and made recommendations on the marketing channels for wine but few were acted upon. Given the Commission’s broad mandate, the power of the breweries and wine and liquor importers and merchants, this was not surprising. But the difficulties being experienced by the wine industry in both West Auckland and Hawke’s Bay in the late 1940s and into the 1950s began to attract public and political attention and support.

On 26 October 1956, the New Zealand House of Representatives ordered

that a Select Committee be appointed, consisting of ten members to enquire into and report upon the state and prospects of the wine-making industry of New Zealand, the effect of the present law upon the manufacture, distribution, sale, and consumption of New Zealand wine and all other aspects of the industry as the Committee sees fit.

Few select committees have had terms of reference so broad or made recommendations so bold. Paul Groshek gave written evidence to the Committee. His submission was by far the most colourful, visionary and unequivocal, in ideas as well as language.

It must be understood by any practical wine-maker and wine connoisseur that most beneficial wines are natural dry table wines.

. . . there is no reason why these people should not be allowed to obtain table wines in grocery shops and in restaurants with meals. This would be example of how the wine should be drunk and would lead to sober drinking, as no connoisseur is a drunkard or alcoholic!

It is important that any restaurant wishing to supply wine with meals should be allowed. If the place is good enough to have a meal it is good enough to have a drink.

No tied house should be allowed to have a monopoly to supply prize wine with full-page advertisement in papers to a public that does not know what table wine is. The wines should strictly comply as pure grape wines and let the public find out for themselves, what is good about wine.

The wine would be bottled by the wine-maker and reach the consumer direct. It would be preferable in half-size bottles. The handling and distribution laws of wine are such where wine is regarded as more dangerous than explosives and breeds lawbreakers. This is irrational.

New Zealand wants more grapes to produce wine. It is of no use complaining of importing wine from cheap labour producing countries and we exploiting labour of cheap sugar producing countries. To produce more grapes we need more wine growers.

This is not politics or a matter for referendum, when one half people say to other half when to drink or eat, and make liberty a mockery.

Nick Delegat and Mate Selak, under the watchful eye of customs officer Warren Leonard, draw off alcohol to fortify their ports and sherries. Marti Friedlander, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

By the late 1950s, social and political attitudes – modified by more distance from the grey days of World War Two – had changed. The Select Committee that reported to the House of Representatives on 14 September 1957 recognised this shift in opinion and acted. Recommendation 27 reads ‘that approved restaurants be licensed to supply New Zealand light table wine with substantial meals’. No booze was to be served with a mere snack. By 1960, legislation was in place. The nights of patrons smuggling bottles into venues under dresses or in deep pockets, and restaurants risking prosecution for serving wine, were over. That the West Auckland member H. G. R. Mason (Labour, Waitakere) moved the resolution was no coincidence.

Other recommendations took longer to realise. The cautious wording of Recommendation 15 – ‘that wine-sellers’ licences be more freely granted and that an application for such a licence should not be refused because of the existence, or probable existence, of other forms of licence’ – looked forward to the battles to be heard before the Licensing Commission in the coming decades as the breweries and large wholesale liquor outlets protected sales of beer and imported wines and spirits for their hotels and ‘off-licence’ premises. Nevertheless, more wine-sellers’ licences were issued, mainly to the medium-sized firms from West Auckland. Some family wineries even established small stables of wine shops across selected provincial towns, mainly in the North Island. These proved valuable marketing channels until the popularity of table wine soared in the 1970s and most outlets licensed to sell alcohol had no option but to sell New Zealand wine. Frank Yukich of Montana was at the forefront of these battles, always jousting with the breweries. They contested every one of his applications. Through Yukich’s persistence, by the late 1970s Montana had accumulated 30 wine shops throughout the country.

The most far-reaching recommendation of the Select Committee – ‘that wine-sellers’ licences be granted to any grocer of good character who has suitable premises, and who does not sell food or drink for consumption on the premises, unless there is reasonable fear of undesirable social consequences’ – sounds decidedly quaint in the freewheeling early twenty-first century. It took until 1990 before supermarkets were licensed to sell wine. Within a decade of receiving their licences, supermarkets were dominating sales of both local and imported wine. Beer gained access to supermarkets only in 1999. For a short time wine had a marketing advantage over other alcoholic drinks. The value of wine in the trolleys of supermarket shoppers is now worth more than any other single category of food or drink.

Thus, by 1960, the conditions were in place for the development of a quality wine industry in New Zealand. Legislation and cultural attitudes had shifted to allow the growth of wine sales in restaurants, wine shops, and at the cellar door. A group of young wine enthusiasts, many of them descendants of winemaking families, brought experience and new ideas to the business. And companies both large and small were beginning to show that vines and wines of quality could be grown in New Zealand soils and climates across a number of regions. After 1960, the country’s wine production expanded rapidly as the industry went through a regional and varietal revolution.