Templars Hill, Mt Difficulty, Central Otago. Matt Dicey

3

Regional and Varietal Revolution

In the second half of the twentieth century the regional distribution and varietal mix of New Zealand winegrowing was transformed. From an initial base in Auckland and Hawke’s Bay in the 1960s, substantial areas in vines have been planted in turn in Gisborne, Marlborough, the Wairarapa (Wellington), Central Otago and parts of Canterbury. The vine also has established a noticeable presence in the Auckland region at locations beyond its traditional base in West Auckland around Matakana and on Waiheke Island; in the Waikato at Te Kauwhata; and in Nelson.

Contemporaneously with this regional expansion, New Zealand winegrowers changed the varietal mix from hybrids and varieties suitable for fortified wine to the varieties of Vitis vinifera that flourished in the cooler and northern wine-producing regions of France. By the early twenty-first century, each New Zealand region was showing signs of developing its own specialisations in varieties of grapes and in the style of wines being produced.

In the 1960s and 1970s, very little was known about which varieties should be grown where in New Zealand, or the viticultural practices needed to produce grapes with the qualities to make table wines of distinction. Some individuals and organisations subsequently commissioned studies of the suitability of particular localities and regions for grape growing. Examples are those by Derek Milne (Martinborough area and Hawke’s Bay), Wayne Thomas and the late John Marris (Marlborough), and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) and Ministry of Agriculture trials (Central Otago). But even these studies were noticeably silent or unreliable about which particular varieties to plant in different regions. They were often designed to convince people to invest in vine growing in these places rather than to assess growing conditions for particular varieties.

The varietal specialisation that has emerged in different New Zealand localities and regions has resulted mainly from trial and error by the enterprises planting the grapes and by the demands of the market. As the vine was planted in untried regions, few aspiring winegrowers examined all the available scientific evidence and maps and decided ‘this is where this variety should be grown’. Rather, grape varieties considered suitable for the locality were planted and growers and winemakers demonstrated that they were able (or unable) to produce grapes with the desired qualities to make distinctive and appealing wines. Montana’s success in Marlborough with Sauvignon Blanc is an excellent example.

Each of the regions successively colonised by the vine required new learning – with regard to soils of different structure and textures, drainage characteristics, moisture retention, and climates with different seasonal nuances. The pioneering family firms in localities such as Martinborough, Central Otago and parts of Canterbury were seldom sure when they first planted grapes whether they had chosen the right sites or whether they would be successful. In Central Otago, for example, three of the pioneering enterprises – Rippon Vineyards, Chard Farm and Gibbston Valley – have all made excellent still wine from Pinot Noir. The last two have now decided to extend their vineyards or source grapes from localities of Central Otago more recently colonised by the vine where growers from sub-regions such as the Bendigo Terraces have demonstrated their ability to ripen Pinot Noir more consistently.

The major New Zealand companies, alongside the small winemaking firms, have been crucial influences on the dispersion of viticulture in New Zealand. Not only did they invest in the regions, but through letting contracts to grape growers the major firms have helped transform how grapes are grown. For many grape growers, choice of varieties has since been strongly influenced by the advice, even insistence, of the buyers – the winemaking enterprises – which, informally and in written contracts, have specified their preferences. In the early stages of the development of the industry, when grapes were in short supply, almost any fruit were acceptable. Today, the growing of different grape varieties to meet a specified number of tonnes per hectare, often with sugar levels (brix) and acidity also specified by bands, is standard practice.

The country’s leading winemakers gather at the 1970 Viticultural Association field day. The association’s president, George Mazuran – a Croatian immigrant who had been growing grapes and lobbying government in New Zealand for more than 30 years – addresses the group. Marti Friedlander, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

Many of these grape-growing families – especially in Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and Marlborough – were landowners with experience of growing other crops. Talking about what attracted his family into growing grapes, Phil Rose of Wairau River Wines said: ‘We’ve been growing things all our lives really. It was just something different. Vines are relatively easy things to grow once you understand the sort of philosophy of a vineyard.’ The industry survivors now have more than 30 years of experience producing grapes for wine during times when the demands of the wine companies have been escalating. As corporate firms write ever more sophisticated contracts that require, for instance, low and precise yields of Pinot Noir for their premium wines, these grape growers have the understanding of canopy management to respond. They know the environment of the land they own. Many who entered as grape growers have since started their own wineries. Grape growing and winemaking families on their own holdings are equally as skilled – some would claim more skilled – in integrating the quality of grapes required to suit the style of wine they seek. Experience and learning on the ground by winemakers and grape growers have driven the varietal and regional revolutions in New Zealand.

Historical geography of the vine

The historical geography of the vine and wine in New Zealand is usefully viewed in a series of overlapping phases: the period of rural (and associated urban) settlement from the vine’s first known planting in 1819 through to the 1930s; the period between about 1880 and 1920 when the temperance movement and restrictive legislation contributed to reducing the small area in vines; a period of steady growth from a small base during the 1920s and 1930s and rapid growth during the Second World War, followed by a decade of uncertainty, even crisis, as local markets evaporated when imported wines again became available; and the most recent phase, from the early 1960s, when the planting of vineyards recommenced at an unprecedented pace and has continued through the rest of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, interrupted only by the vine-pull scheme of 1986. Changing societal and governmental attitudes, together with changing consumption patterns and changing marketing and distribution channels, have underpinned the latter developments, but this period of buoyant growth was founded on its past, and the period before 1960 reveals much about the culture–environment nexus of the vine and wine.

The vine arrived in New Zealand soon after the first settlement by Europeans. Samuel Marsden (who established the first Church of England mission in New Zealand) planted vines; and James Busby (the first British Resident) made the first wines in 1836. Dumont d’Urville, when he visited Busby in 1840, praised the wine made from these Bay of Islands grapes. It is quite possible that the vine had arrived earlier than this, because ships plied the Tasman from the late eighteenth century and vines were growing in Sydney Cove by the 1780s. In 1838 the writer and explorer J. S. Polack reported that in New Zealand vines were ‘largely cultivated to the northwards of the River Thames’ – that is, in Northland and South Auckland. Maori were quick to cultivate them and supply table grapes to the Auckland and other markets as they seized the opportunities provided by concentrated populations.

As in most New World countries, the vine was also disseminated with the Catholic missionaries. The Marist Brothers established a winery in 1855 at Meanee in Hawke’s Bay (after grapes were first cultivated at Pakowhai), and later moved to Greenmeadows to become the Mission Vineyards. Sociologist and wine writer Jason Mabbett recounts plantings of vines by the Marist Brothers at Whangaroa (1839), Otaki (1850), Gisborne (1847) and on the Whanganui River, near Pipiriki. Wine was made from these grapes. During the second half of the nineteenth century and for the first two decades of the twentieth, when rural settlement spread rapidly, Vitis vinifera, like other crops of European origin, was planted in many parts of the country. Settlers experimented with various varieties as part of the mixed farming systems that they established. Most dairy farms, for instance, also had their own orchard until well into the twentieth century.

But the vine was not one of the perennial crops commonly found on all agricultural holdings of the predominantly Anglo-Celtic population. It usually appeared in one of two forms: as a family vineyard or vinehouse (glasshouse) in the British tradition, usually for table grapes; or on land owned or used by people from cultures with traditions of wine – the 1840 Nanto-Bordelaise Company of Langlois in Akaroa, the Spaniard Joseph Soler in Wanganui (1869), Breidecker at New Plymouth, the Vidals of Hawke’s Bay, Croats from the Dalmatian coast on the gumfields of Northland and in other parts of New Zealand.

Colonial commentators frequently tied the vine to non-British cultural groups. Mabbett quotes Petre (1842) who pointed out:

One drawback upon the cultivation of the vine, the olive and the mulberry is that the English really know nothing about it. To cultivate them to any extent we shall require French and German cultivators, to whom the most liberal encouragement should be given.

Similar arguments were made in the regional press over the qualities of German settlers. The Nelson Examiner, commenting on the arrival of a shipload of settlers from Germany in the early 1840s, wrote: ‘No immigrants are more valued than the Germans and we hail the intended cultivation of the vine by them with unfeigned pleasure.’

Vidal vineyards, Havelock North, Hawke’s Bay, 1920s. Spanish immigrant Anthony Joseph Vidal established Vidal Estate in 1905. French, German, Croatian, Spanish, and other continental Europeans nourished a small tradition of winemaking in New Zealand through the years of restrictive liquor legislation, when most New Zealanders preferred beer. Henry Norford Whitehead, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, 1/1-004863-G

Nevertheless, some settlers of British origin were important in establishing commercial vineyards in the nineteenth century. Most of them were wealthy landowners who preceded their planting by investigating winegrowing in Europe, California or Australia. Beetham planted vines in the Wairarapa in 1883. Tiffen’s vineyard to the west of Napier in Hawke’s Bay grew to almost 15 hectares by 1905 but declined when a prohibitionist became manager of the farm. Chambers planted a hectare of vines at Te Mata in 1892 and established a winery there. The Levets of Whakapirau (now Wellsford) were of more modest means, arriving in New Zealand as Albertland settlers in 1862. They established a vineyard and commercial winery near the Kaipara Harbour in the 1860s.

The Croatian-born, Italian-trained scientist Romeo Bragato provides a lively evaluation of the potential of the New Zealand industry at the end of the nineteenth century. His south-to-north journey from Central Otago reads something like the rural excursions of Arthur Young or even Robert Louis Stevenson into the continental Europe of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His enthusiasm for the potential of New Zealand and its regions for vines is unbounded, and two characteristics of his observations are particularly relevant to the themes of this chapter: first, he was able to observe vines growing in almost every region of New Zealand; and second, the vines that he mentions are mainly Vitis vinifera.

Two of his other discoveries also provide a clue to the future. He identified Phylloxera vastatrix, the root-aphid that had devastated the European vineyards from the late 1860s, as well as other diseases that had earlier caused severe problems in Europe, notably öidium or powdery mildew. Nevertheless, most of the vines he observed were healthy and well cared for. Geographically, therefore, by the opening of the twentieth century vinifera grapes had been grown in most regions of New Zealand. Much of this regional experience was to wane or disappear in the next 60 years. Although Bragato’s investigation of New Zealand’s prospects for viticulture resulted in the establishment of the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station in 1898 and his appointment as Government Viticulturist there in 1902, he left for Canada in 1909, disillusioned by his experience when he did not receive the support from the government that he had expected.

Larger social and cultural forces influenced changes to the area in vines between 1900 and 1950. The temperance movement had a powerful impact. Between 1880 and 1920, the state responded to the electorate by regulating to restrict the sale of alcohol, and particularly wine. Licensed wine shops were allowed, but over the whole country only four licences were granted. Sale of wine by single bottle from wineries was not permitted. Some restrictions were geographically specific. From 1895, certain electorates, including part of West Auckland, voted to go ‘dry’. No alcohol could be sold in them even from their wineries. Such restrictions affected small wineries in particular because they found it difficult to get access to the many hotels controlled by the breweries.

Temperance combined with widespread prejudice against non-British citizens to cultivate a suspicion toward wine and its makers. Prime Minister W. F. Massey warned in 1914 of

the manufacture and sale of what is called Austrian wine . . . a liquor that is sold in the district north of Auckland. I have never seen the stuff, but I believe it to be one of the vilest concoctions which can possibly be imagined. I do not know what its ingredients are, but I have come across people who have seen the effects of the use of Austrian wine as a beverage, and from what I have learned it is a degrading, demoralising and sometimes maddening drink . . .

Many Dalmatians had immigrated to New Zealand in reaction to the political turmoil in the Balkans and the incorporation of their province into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. These were the ‘Austrians’ that Massey is referring to. Their lot, and the attitude of some members of the Anglo-Celtic society toward them, was to deteriorate as the First World War progressed.

The nascent industry suffered as a result of the temperance movement and such suspicion towards non-British citizens, together with the penchant for beer among New Zealand’s working class and the preference of social elites for imported wines. By the 1950s, New Zealand’s annual wine consumption was less than 2 litres per head compared with France at 96 litres. Beer consumption in New Zealand was over 100 litres per head – third in the world after Belgium and Australia. At the same time, France was consuming less than 30 litres of beer per head. The New Zealand brewing interests exerted enormous economic and political power in distributing their products.

The First World War, the 1930s Depression and the Second World War began to change these conditions and set the environment for the rise of the modern wine industry. The experience of New Zealand troops serving in continental Europe, shortages of imported wines – indeed all alcohol during the Second World War – and the establishment of a series of wineries committed to earning a full-time living in the industry, all contributed. Modest increases in the area in vines began during the Depression but accelerated rapidly during the Second World War when alcohol of any description was in short supply. American troops stationed in New Zealand increased the demand. Wine consumption from New Zealand grapes increased rapidly, but it was almost all fortified wine, a style that was not playing to New Zealand’s environmental strengths.

While the period from colonisation to 1960 represents the prehistory of the New Zealand wine industry, it is the regional and varietal revolutions since 1960 that have shaped its modern configuration.

Regional revolution

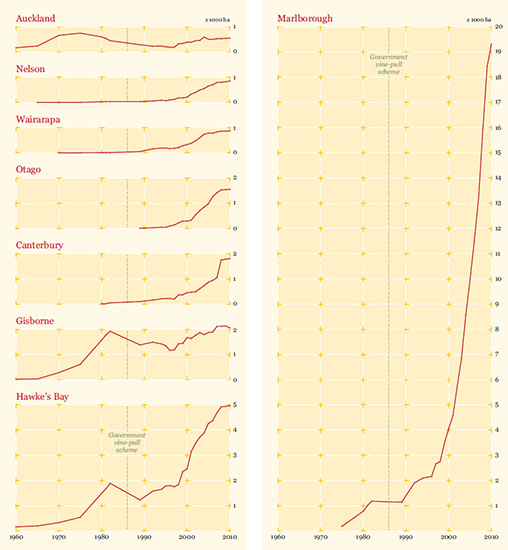

Strong growth in the area in vines has characterised the period from 1960 to 2010 and beyond (Figure 3.1). From a low base in 1960, the planting of vineyards quickened after 1975 before a flat period between 1982 and 1985. The government-sponsored vine-pull scheme of 1986 saw over 1500 hectares of vines removed. More vines were planted immediately, and after 1995 planting again accelerated. The growth showed little signs of slackening until the recession of 2008 slowed plantings in some regions, but most enterprises have recovered, and now many grape growers and wine enterprises are planning substantial increases in their vineyards. Accompanying the increase in area in vines has been substantial investment in wineries and associated plant by both large corporate and family firms.

The New Zealand industry that developed is highly oligopolistic. At the millennium, four firms – Montana, Corbans, Villa Maria and Nobilo – produced about 80 per cent of the wine. Almost 350 mainly family winemaking firms, and about 700 family-based grape growers, made up the rest of the industry. Over the last twenty years, takeovers and mergers have transformed the ownership structure of the largest firms. Montana bought Corbans and then in 2000 Pernod Ricard acquired Montana. In 2011, contract winemaker and exporter Indevin Partners New Zealand made use of the fermentation and storage tanks in Gisborne that had been underutilised as the New Zealand wine industry focused its attention on the rapid growth of the Central Otago, Wairarapa, Marlborough and Hawke’s Bay regions.

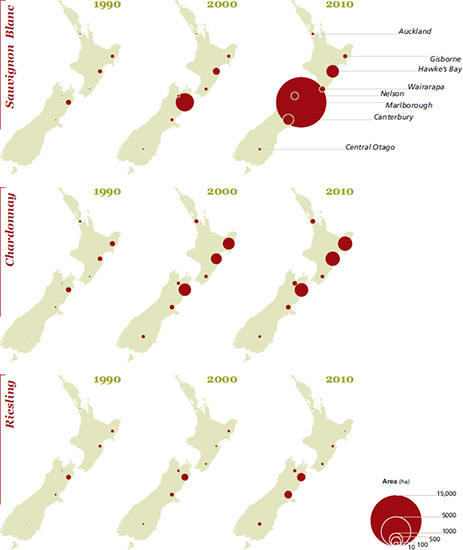

Table 3.1 The five regions with the largest area in vines (% of the national total)

In 1960, grape growing and winemaking were concentrated in Auckland and Hawke’s Bay (Table 3.1). Together, these two regions grew 85 per cent of New Zealand’s total area in vines. Since 1960, a series of regional growth spurts have transformed the distribution of vines in New Zealand. Four main stages are discernible. First, in a frequently neglected phase of the industry, an expansion took place in the Auckland region during the 1960s and early 1970s. Associated with this development was growth in the nearby Waikato region, dominated by the Te Kauwhata locality. Second, during the 1960s and 1970s, came the rise of Gisborne as a major winegrowing area. By 1980 it was growing more vines than any other region although only a single percentage point above Hawke’s Bay. The third stage, the rise of Marlborough, began in 1973, but only in the 1980s did its area in vines begin to grow rapidly. Its growth rate accelerated in the 1990s until by 2000 it had 41 per cent of the country’s vines. Fourth came the rise, mainly in the last decade, of other regions – notably Canterbury (especially Waipara), the Wairarapa, Nelson and Central Otago. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, except for a brief period in 1990, Hawke’s Bay has been one of the top two regions by area in vines and has played a distinctive and vital role in the New Zealand industry.

Figure 3.1 Regional dispersal of vines in New Zealand, 1960 to 2010

Figure 3.2 Area in vines in eight New Zealand regions, 1960 to 2010

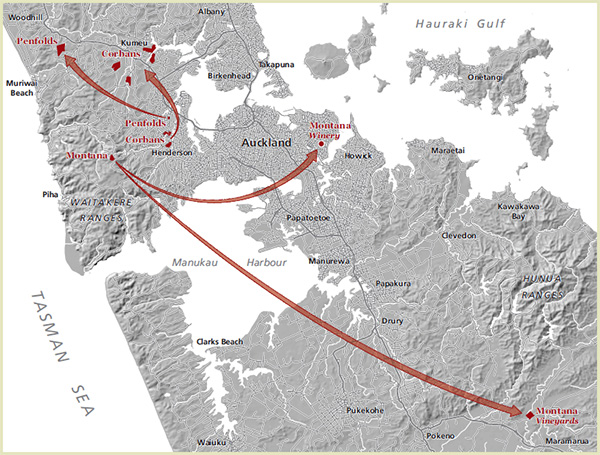

The expansion in vineyard area gained real momentum after 1965. Auckland was the region that grew most rapidly in the period 1965 to 1970. Three major firms – Corbans, Montana and Penfolds – began a rapid expansion of their vineyard area (Figure 3.3). Each had different motives for relocating or expanding. Corbans, the largest enterprise at the beginning of the expansion, was being pressured by urban encroachment close to its vineyards in Henderson, West Auckland. It could capitalise on this land’s urban potential by selling some vineyards and buying and developing more suitable land cheaply within reasonable distance of its winery. Meanwhile, the Yukich brothers had become closely involved in their father’s 5 hectares of grapes and small winery called Montana in the Waitakere Ranges. Working from a restricted site, they began a period of aggressive expansion of their business that accelerated when the American firm Seagram bought 40 per cent of Montana in 1973. By the end of the century, Montana would be making wine from about 3000 hectares of grapes. Finally, Penfolds of Australia entered the New Zealand industry by acquiring a large family vineyard and winery in Henderson owned by the Averill family.

From today’s perspective and state of environmental knowledge, it seems surprising that in their first large plantings these three firms all chose sites on the outskirts of the Auckland metropolitan area. Within a decade all except Corbans’ Merlot vineyard in Kumeu were out of production. Had this expansion taken place a decade or so later it is likely that the choice of sites, even within the Auckland region, would have been more sophisticated and the vineyards of higher quality. In the 1960s, however, knowledge of suitable varieties and clones, of canopy management, and the virus status of New Zealand vines was rudimentary. The South Auckland vineyard of Montana would have been much more successful had it been located in the eastern lee of the Hunua Ranges. The Penfolds vineyards near the west coast were within 10 kilometres of the very successful Rothesay vineyards of Collards in the Matua Valley that is much less exposed and receives noticeably lower rainfall on more versatile soils. Two of the Corbans vineyards in Kumeu were later sold and revitalised. Under different ownership and with better canopy management, they have produced some fine Merlot.

From 1970, a second period is characterised by the rise of Gisborne and Hawke’s Bay. By 1980, both Gisborne and Hawke’s Bay each had twice the area in vines of the Auckland region. Gisborne’s growth resulted from Montana Wines continuing its aggressive expansion by letting contracts for landowners to grow grapes. Corbans and Penfolds were quick to respond by arranging contracts with other landholders in Gisborne. A series of well-established, but smaller, Auckland-based wine companies – such as Babich, Nobilo and Matua Valley – followed the larger companies and sourced grapes from these new regions.

Figure 3.31960s dispersal of vineyards owned by Corbans, Montana, and Penfolds to urban peripheral land on the northwestern and southern fringe of Auckland

Growth in the North Island regions was soon rivalled by new developments in Marlborough, with Montana Wines again at the forefront. In the early 1970s, Frank Yukich, the managing director of Montana, had decided that Marlborough was a region that offered strong environmental opportunities for grape growing in New Zealand. In this decision he was influenced by Wayne Thomas, formerly a government plant scientist, by now in charge of national viticulture for Montana. Some limited scientific evidence – more to convince the Montana board than to provide definitive judgement – supported these views.

Throughout the 1960s, the Corban family continued to expand their footprint in West Auckland. In 1969, they bought 121 acres in Taupaki. Here the family (from left, Khaleel, Wadier, Assid, and Najib, and on right, David and Joe) bless the new plantings. Marti Friedlander, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4

Grapes were first planted there in the winter of 1973. Despite the heavy losses of young vines over the first summer, the quality of the grapes quickly established that Marlborough was a region of unusual potential. Between 1975 and 1980, Marlborough’s area in vines increased more rapidly than anywhere else, and by 1990 it had a slightly larger area in vines than any other region. As well as planting its own vines, Montana again let contracts to landowners in the region. The Marlborough bonanza had commenced. By 2000 it was growing over 40 per cent of New Zealand’s grapes and by 2010 over 60 per cent.

Several economic and environmental advantages favoured the expansion in Marlborough. By viticultural standards, land prices there were low because the Wairau Plain was being converted from quite extensive sheep farming with some cropping and commercial seed production, and large areas of land were available. Marlborough’s low annual rainfall, long growing season and mainly well-drained soils of low to moderate fertility suited many varieties of vines, although uncertain rainfall demanded irrigation, especially in their establishment phase. Most growers continued to irrigate, in difficult periods and with careful monitoring, even after the vines were established.

Although regional shifts were occurring, all major grape-growing regions – Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and Marlborough – grew rapidly in the late 1970s and early 1980s. For instance, in the five years between 1980 and 1985, both Gisborne and Hawke’s Bay each added over 1000 hectares to their area in grapes – a rate of growth that surpassed that of Marlborough. The rapid expansion of the early 1980s had its detrimental effects. Intense competition for a share of the market saw prices for wine in New Zealand plummet in the mid-1980s. That drove a number of companies into receivership and led to several takeovers and mergers. In 1986 the government sponsored a vine-pull scheme as an economic remedy, providing a subsidy of $6,175 per hectare to remove vines. This response was quite uncharacteristic of the neo-liberal Labour government elected in 1984 and indicates the lobbying power of firms in the wine and liquor industry at that time. The total direct subsidy for the vine-pull scheme was almost NZ$10 million. Growers removed over 1500 hectares of vines, most of it from Gisborne (586 ha), Hawke’s Bay (534 ha), the South Island (210 ha) and Auckland (162 ha).

In retrospect, the vine-pull scheme was an unexpected opportunity for the wine industry. By the mid-1980s, viticultural knowledge and practice in New Zealand had improved considerably. The scheme encouraged some wine companies and grape growers to change the varieties of grapes they were growing, to improve the virus status of their vines, to find a better combination of rootstock and variety, to modify their trellising systems and to plant the best available clones. Although for many wineries problems of cash flow necessitated the uprooting of vines, the majority of enterprises quickly re-established their area in grapes. Some grape growers took the opportunity to leave the industry, but the recovery of the area in vines in the major grape-growing regions demonstrated that by far the majority of growers remained. New grape growers and wineries more than replaced those which left. By 1995, Marlborough and Hawke’s Bay both had more land in vines than ever before, and even Gisborne, where the largest area in vines had been pulled, had surpassed its 1985 total by the late 1990s.

The last two decades of the twentieth century saw the realisation of the third major stage of regional dispersion away from the two traditional regions of Auckland and Hawke’s Bay. By 2000, Canterbury (mainly the Waipara area) had replaced Auckland as the fourth largest grape-growing region in the country and both Central Otago and the Wairarapa were growing fast. In these last two cases local landowners and purchasers whose scale is small have led the growth, with the major corporations and the medium-sized established wine companies slow to buy land or plant grapes. Canterbury, Central Otago and the Wairarapa each has a distinctive group of mainly local, pioneering firms (usually family enterprises) which both grow the grapes and make the wine. The many small vineyards in a region such as Central Otago have found innovative solutions to overcome their lack of scale. The Central Otago Wine Company, for instance, has made individual batches of wine under contract to the owners of small vineyards who market their own wine. Since the early 1990s, new capital has entered the industry in each of these regions and has increased the scale of operations.

Since 1980, the main vineyard regions have also experienced some revealing local readjustments. The forays into new localities have been influenced by both high prices for land in the core regions and a more sophisticated search for new vine environments with the potential to make fine wines. Existing enterprises, both intra- and extra-regional, are diversifying their production by buying land in regions with special qualities for particular varieties or in localities with a different potential from their existing site. New enterprises, often with substantial capital, sometimes from overseas, are seeking their own new and distinctive sites, often in localities where the vigour of vines is lower.

Numerous examples exist of these new areas being explored within traditional regions. In Marlborough the move into the Awatere Valley to the southwest of the region is a good example. In Hawke’s Bay the planting of grapes on sites such as the upstream terraces of the Ngaruroro River or the rapid development during the 1990s of the Gimblett Road locality created another layer of local complexity. Even in the Auckland region, a new array of mainly small vineyards and wineries have appeared, this time about an hour’s drive from the northeastern edge of the city, at Matakana east of Warkworth. Simultaneously, the area in grapes and the number of wineries have increased rapidly in the prestigious Auckland locality of Waiheke Island.

Alongside this regional growth and specialisation, a corporate geography has also developed to shape the wine industry. Auckland’s position as the original home of many wineries has seen it develop into the industry’s corporate centre. Early decisions by companies such as Montana and Corbans to relocate or extend their original winery in Auckland have proved to be locationally sound. In a small economy such as New Zealand, where the major local market is concentrated in Auckland, the suppliers of bottles are in Auckland, and Auckland is the main export port for wine, it makes sense to have processing, storage and bottling facilities there.

And such decisions have affected which facilities in the filière of the enterprise (the network which contributes to the production of fine wine) go to other regions. Montana and Corbans both had crushing plants, fermentation tanks and some storage facilities in Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and Marlborough. When the Villa Maria group (the third largest company) was created in the mid-1980s, in addition to its Auckland winery it had two in Hawke’s Bay (now Vidal and Esk Valley). It makes wine in all three while maintaining its main bottling and distribution centre in Auckland, the home of the original Villa Maria. Some of the middle-sized wine enterprises transport grapes or partly finished wine to Auckland for finishing. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, increasing investment in wineries by medium-sized firms began to flow into the fastest-growing grape regions. Small family firms almost always have on-site wineries.

Varietal revolution

Vinifera varieties dominated the fledgling wine industry in nineteenth-century New Zealand. Much of the accumulated knowledge about growing these classical varieties disappeared during the first two decades of the twentieth century when the wine industry declined. The industry’s period of modest growth from the 1920s was propelled by lesser varieties – first by the American Vitis labrusca varieties and then by the hybrid varieties. Romeo Bragato had imported American vines into New Zealand when he was charged with combating the phylloxera that he had discovered. He grafted vinifera varieties that would produce fine wine on to disease-resistant rootstock. But when he left New Zealand in 1909 and his grafting programme was abandoned, the labrusca vines were planted on their own roots.

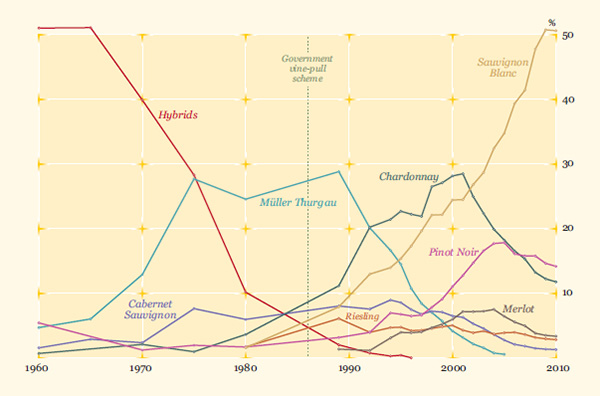

Figure 3.4 Vine varieties in New Zealand, 1960 to 2010

The Concord sport, Albany Surprise, for a long period the most common New Zealand table grape, derived from these vines. From the mid-1850s, plant breeders in France experimented with crossing Vitis labrusca and other American vines with Vitis vinifera. They were attempting to breed vines bearing grapes with interesting characteristics, and to provide wine varieties more resistant to the fungus disease öidium that was seriously affecting the French vineyards. Some interesting hybrids resulted, especially from the plant breeder Seibel, but they all had a flavour derived from the labrusca parentage. It became known as ‘foxy’. It was not surprising that the disease-resistant hybrids found their way to New Zealand. In the 1930s and 1940s, when vineyard area was beginning to expand, they were distributed from the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station and planted widely.

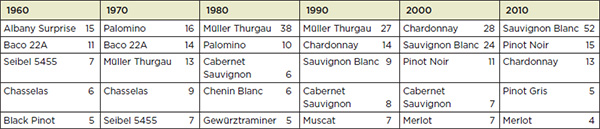

Table 3.2 The five principal grape varieties of New Zealand, 1960–2010 (% of the national total)

The first reliable statistics, in 1960, show the varietal mix that had resulted from the plantings of the period from the 1920s (Table 3.2). Hybrids dominated. Almost 50 per cent of the vines in production in 1960 were hybrid grapes. Seibel 5455 was the dominant red hybrid, and Baco 22A the dominant white. Among the vinifera varieties, Palomino and Chasselas each had about 20 hectares, and the Riesling-Sylvaner cross (now called Müller Thürgau in New Zealand) just under 20 hectares. Palomino is used in Europe to make sherry in very warm climates; and Chasselas, a variety with low acid, is used mainly for bulk wines, usually in cool climates. Both have the advantage of being reasonably resistant to diseases and are heavy croppers. The Ministry of Agriculture vineyard survey of 1960 recorded just 3 hectares of Chardonnay being grown in New Zealand and 6 hectares of Cabernet Sauvignon, almost all of them in Hawke’s Bay. Considering this unpromising base, the development, in the next 30 years, of an industry producing quality table wines from almost all of the best varieties is a notable achievement.

The hybrid varieties, especially the Seibel 5455 and 5437 together with Baco 22A, survived for some time. As late as 1980, with Palomino added, they made up a larger area of the national vineyard than all other varieties combined. During the initial expansion of vineyard area in the 1960s and 1970s the hybrids continued to be planted in substantial numbers. In 1975 there were almost 500 hectares of hybrids in production compared with 179 hectares of Cabernet Sauvignon and 52 hectares of Chardonnay. But it was the vinifera cross, Müller Thurgau, which dominated the planting of vines in the 1970s. By 1980 there were 1819 hectares of that grape growing in New Zealand – 737 in Hawke’s Bay, 638 in Gisborne and 324 in Marlborough. No other variety reached 100 hectares in Marlborough and only 33 hectares of Sauvignon Blanc was planted there by 1980. The Riesling-Sylvaner cross known as Müller Thurgau was dominating even the exciting new regions (Table 3.3).

The dominance of Müller Thurgau during the 1970s is striking. It reflects the requirements of the New Zealand industry in that period. Müller Thurgau grows well over much of New Zealand and is relatively disease free. It yields well. It is not difficult to attain over 20 tonnes per hectare and have fruit of reasonable quality. In the early 1980s much of New Zealand wine was marketed in 4- to 6-litre cardboard casks and Riesling-Sylvaner was the dominant variety in these. As companies competed for market share and the demand for simple, fruity table wine was growing, the large producers could not afford to neglect it. Some companies, led by Nobilo, very successfully marketed their Müller Thurgau in bottles, a feat that they were later to repeat with their very successful 1990s promotion of the label White Cloud – initially Müller Thurgau and Muscat in another guise.

The rise of the classical vinifera varieties

Yet the evidence was there, in the plantings and in the wines, that the mainstays of the European industry – the viniferas – would also produce the best wines here and dominate the New Zealand industry. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, two winemakers in particular – Alex Corban and Denis Kasza (working with Tom McDonald) – began to experiment with and produce varietal wines from Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay respectively, or Pinot Chardonnay as it was then called. The quality of the McDonald’s Cabernet Sauvignon was readily apparent in the Bakano, marketed first in bottles and later casks, but it was fully confirmed when McWilliam’s bottled it as the varietal Cabernet Sauvignon. All the wine commentators of the time, and the books on the industry since, applauded its quality and impact. The 1965 McWilliam’s Cabernet Sauvignon is legendary. This potential was demonstrated in other regions with the excellent Cabernet Sauvignons and Pinot Noirs that were made by Nick Nobilo from Huapai, West Auckland grapes, especially the Cabernet and other blends of 1976. Glimpses of Romeo Bragato’s enthusiastic reading of the potential for many regions of New Zealand to produce fine wines had begun to emerge.

The transformation of the varietal mix of the New Zealand industry had begun in the early 1980s but was hastened by the vine-pull scheme of 1986. Because it was newly established, by 1980 Marlborough already had a larger area in Chardonnay, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewürztraminer, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinotage and Pinot Noir than Hawke’s Bay. Gisborne had the largest area in Chardonnay, Gewürztraminer and Pinot Noir of any region. The varietal mix at any date was strongly influenced, therefore, by the history and the stage of viticultural development of each region. Varieties removed by winemakers and grape growers during the vine-pull also gave a good indication of the direction of the industry. In descending order the varieties removed were Müller Thurgau (507 ha), Palomino (137 ha), Gewürztraminer (109 ha), Chenin Blanc (98 ha), Riesling (97 ha) and Cabernet Sauvignon (62 ha). The large area of Cabernet is surprising but was influenced by enterprises with cash-flow problems which needed the money to survive, as well as by adjustments in regions where this variety is difficult to ripen. The early dominance by variety was soon to change as new vineyards were planted in Hawke’s Bay, new regions were developed, and the opportunities of replanting were realised.

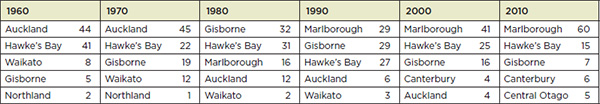

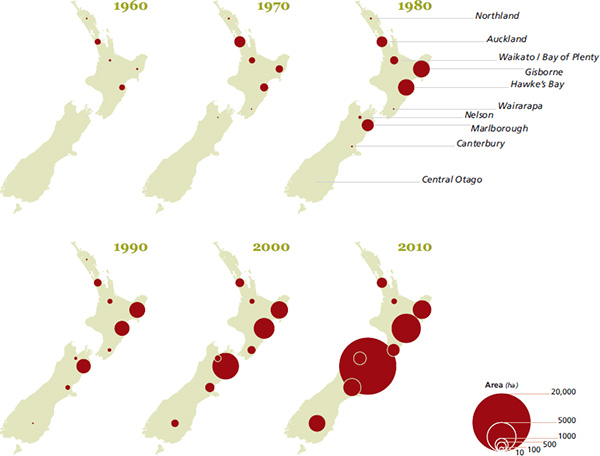

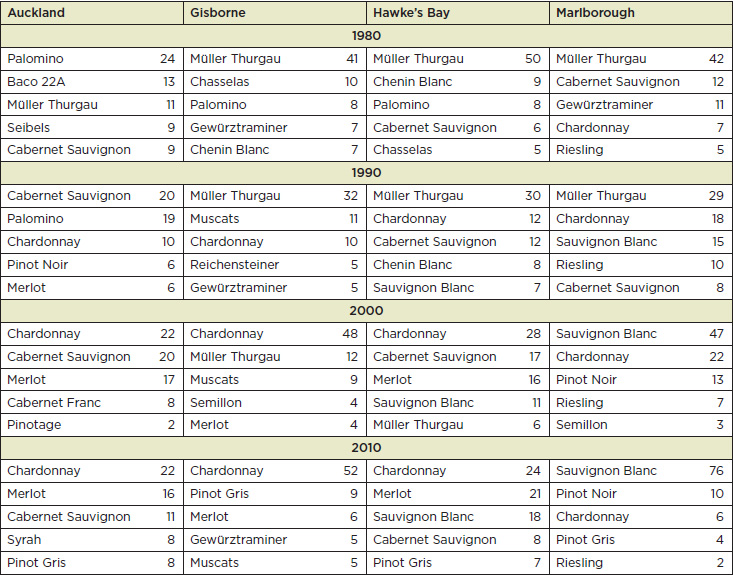

Regional specialisation in varieties

By the 1990s, some regional specialisation in varieties was apparent in the larger regions (Table 3.3). In 1990, Müller Thurgau was still the dominant variety in Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and Marlborough, but the future was clear because Chardonnay was the second most-planted variety in two regions and the third in the rest of the country. By 2000, Sauvignon Blanc had streaked ahead in Marlborough but Chardonnay was the top variety in all three other regions. Gisborne trumpets itself as ‘Chardonnay Capital’ and the figures show that this is so. It also remains ‘Bulk-wine Capital’. When the area in Müller Thurgau and the Muscat varieties (remnants of the 1960s and 1970s experience) are combined, they total almost the same area as Chardonnay. Hawke’s Bay is the single major producing region where red varieties are dominant. Despite Chardonnay having the largest area, the combined area of the two Bordeaux varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, is higher than that of Chardonnay. Hawke’s Bay’s versatility is seen in the substantial area of Sauvignon Blanc being grown there.

Figure 3.5 Regional dispersal of Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, and Riesling, 1990, 2000, 2010

Figure 3.6 Regional dispersal of Pinot Noir, Merlot, and Cabernet Sauvignon, 1990, 2000, 2010

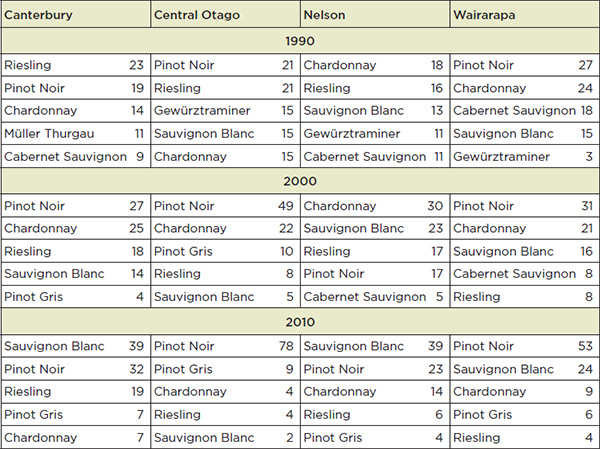

Table 3.3 The five dominant grape varieties for four regions (% of regional totals)

Marlborough, though, is Sauvignon country, with 47 per cent of its vineyard in this aromatic variety. New Zealand’s reputation for making fine wine continues to be built unduly on the distinctive qualities that Sauvignon assumes in the Marlborough terroir. Marlborough is also the only major region where Pinot Noir is one of the top five varieties. In the 1990s, most Marlborough Pinot Noir was blended with Chardonnay in Méthode Traditionnelle. With the quality of the still Pinot Noirs coming out of Marlborough by 1998 and Montana’s plans to develop Marlborough into a major still Pinot region, the area in this variety has continued to grow. Auckland, although having a much smaller area in vines, had a similar mix of varieties to Hawke’s Bay in 2000. Thirty-seven per cent of its vines were in Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, reflecting the uniqueness of the Matakana and Waiheke Island environments and the skill of its grape growers and vinifiers in making quality Bordeaux-style reds, as well as the ability of the rest of the Auckland region to grow these varieties.

In 2000, each of the remaining regions of New Zealand had fewer than 1000 hectares of grapes although they were growing rapidly. For instance, as recently as 1980, Wairarapa (the locality of Martinborough) had only 7 hectares in vines, while Central Otago had fewer than 20 hectares. In 2000, Central Otago was growing over 220 hectares and the area in vines in the Wairarapa was over 300. As viticulture has diffused south, the varietal mix becomes distinctive (Table 3.4). Pinot Noir, in particular, but also Riesling and Pinot Gris, become proportionally much more important. By 2000 in Canterbury, Central Otago and Wairarapa, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay dominated.

In 2010, in both Central Otago and the Wairarapa, Pinot Noir was the most planted variety. It was Wairarapa that established New Zealand’s reputation for making Pinot Noir still wines during the 1980s, with parts of Central Otago and a few examples of wine from Canterbury also showing their potential in the same decade. Central Otago has enhanced its reputation, and other regions, notably Nelson and Marlborough, have shown that they can compete in making Pinot Noirs of quality. Distinctive wines made from Riesling, Pinot Gris and Sauvignon Blanc also originate from all four regions and, like Marlborough, they also have the option of producing Méthode Traditionnelle from Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

An ongoing revolution

This New Zealand story has contrasts, as well as parallels, with the French experience that inspired Dion and Gadille. The transformation of New Zealand viticulture and winemaking from an industry dependent on hybrid vines and fortified wines to one producing quality table wines has been extremely compressed. It took just 50 years. This transformation is impossible to compare with the long-term development of the French industry where the process extended from several hundred years BC and involved the gradual selection of vines that would yield grapes of quality in the cooler climates away from the Mediterranean. However, phylloxera and hybrid vines are key points of historical reference for both countries.

Identification of phylloxera in the late nineteenth century in New Zealand, and the availability of the American species and hybrid vines developed in France, and sold by the state in New Zealand, were important. These, combined with the absence of a culture of wine, and the presence of a temperance movement, all contributed to delay the development of a table wine industry for almost a century. In the interim, Croatian and other winemakers were responding to demand and to the population’s prevailing attitude towards alcoholic drinks by maintaining a fortified wine industry. And some made remarkably good wine. The Australian story is similar although the dates are different and the ethnicity of the pioneering families very different. For a socio-political movement such as temperance to have such a powerful effect on the wine industry would seem highly unlikely in France, Italy or Germany.

Table 3.4 The five dominant grape varieties for four regions, 1990–2010 (% of regional totals)

The transformation of the New Zealand industry occurred in a lightly regulated environment compared with the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée legal framework. Corporate and family firms planted different vinifera varieties in existing and new regions because they saw the potential of the industry in a range of natural environments. In this sense, the New Zealand industry has, despite the radical break in this tradition imposed by the temperance movement and the reaction to phylloxera, some similarities with the long empirical experience (under different conditions of transport and technology) that led to the strong regionalisation of varieties in France.

Such empirical experience of bringing out the best in varieties (and blends of varieties) in different environments was later written into the French appellation laws of 1935. New Zealand regions began to show their potential for different varieties as viticulturists and winemakers understood their new environments using advanced technical knowledge. Recently, more formal recognition of geographical indications in the New Zealand industry began with the submission of a list of localities and regions to the then European Community in 1981 and the voluntary phasing out of the use of French and other European names. After a period of debate within the New Zealand wine industry over the appropriate resolution at which names should initially be defined, rules were written in a generic manner for all rural industries as the Geographical Indications (Wines and Spirits) Registration Act 2006. This defines truth in labelling by regions and varieties. It has yet to be activated.

Although the transformation of the geography of New Zealand winegrowing has been unusually rapid, its potential remains unrealised. The matching of varieties to sites and the blending of different varieties to make distinctive local wines are still tentative. Some of the regions have scarcely two decades of experience of growing particular varieties, not always virus free and not always with the best, or right, mix of clones. With a variety such as Pinot Noir, for example, the recent evidence demonstrates that fine wines are being made from it in a number of regions. With appropriate vineyard management for different sites, more experience of vine phenology, more understanding of its vinification, and more years of different weathers, New Zealand is now in the fortunate position of having a number of different styles of Pinot Noir emerging from many terroirs.

Experimenting with producing distinctive wines by judicious blending of different varieties has hardly begun in New Zealand. The last decade has seen major advances in blends of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot and Malbec, or Merlot, Malbec and Cabernet Franc. But each region, or rather each locality, may require its own particular blending to achieve its potential. Some fine late-harvest dessert wines have been produced in New Zealand, notably from Riesling but also from Sauvignon Blanc and Gewürztraminer. Blending of different white varieties, including different blends for different terroirs, may produce an outstanding dessert wine. Who would be bold enough to suggest that each variety and clone of Vitis vinifera, when transferred to the New Zealand environment, may not perform differently in its new homes, and blended with another or others, be even more special?