Chard Farm in the Kawarau Gorge. Rob Suisted/ when he visited Central Otago in 1972: www.naturespic.com

8

Central Otago

In certain parts of this district, where a good aspect and well-sheltered spots are available, the cultivation of the vine may be undertaken, but judgment must be exercised in the selection of varieties to be planted, and cultivation and pruning methods must be adopted that meet the requirements of the colder vine-growing regions.

– Romeo Bragato (1895)

After a Lincoln College seminar in 1976, Tom McDonald, the managing director of McWilliam’s Wines in Hawke’s Bay, asked Ann Pinckney her plans when she graduated with her Master’s degree in horticultural science. She replied: ‘Grow grapes in Central Otago.’ The sceptical Scot’s reply was unequivocal: ‘You’ll never grow grapes down there, lassie!’ McDonald’s response captures a common attitude among members of the established industry of the time who were almost all growing their grapes in the North Island. They made their judgements on the basis of their experience in regions like Auckland, the Waikato, Gisborne and Hawke’s Bay where variability in temperatures is less than in regions with a more continental climate such as Central Otago.

Bob Knappstein, the highly respected McWilliam’s viticulturist, responded similarly

On the day of the visit, 16 December, Riesling-Sylvaner were still partly in flower and on the customary optimum period to harvest, this will make for a late harvest in mid-April. . . . Two fellow grape growers endorsed that this variety would have been flowering at this stage in mid-November in Auckland.

Viticulturists frequently relate events in the phenology of the vine – such as bud burst, flowering or veraison – to local climatic conditions. Knappstein was arguing that vines growing in Central Otago would not have sufficient time to ripen their crop. But Central Otago is more than eight degrees further from the equator than Auckland. During Central’s growing season, days are noticeably longer and climatic regimes are quite different. The later flowering of all grape varieties in Central Otago is itself a response to lower spring temperatures. Such late flowering helps protect the vines from late-spring frosts. Providing that sufficient solar energy is available later in the season to ripen the grapes, the late flowering need not be a problem. Moreover, low precipitation in Central Otago means that picking is less likely to be hurried by rain, although an early autumn frost may result in senescence of the leaves. Viticulturists now argue that Central’s long autumn with warm days and cool nights stimulates the transfer of flavour and colour compounds into the berries of Pinot Noir.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, therefore, Central Otago – not Marlborough or Wairarapa or Nelson or Hawke’s Bay – became the focus of the climate/vine debate in New Zealand. Between 1967 and 1972 the journal Wine Review (edited by Dick Scott) ran a series of articles on the Ministry of Agriculture’s grape trials on R. V. (Larry) Kinnaird’s orchard at Earnscleugh, Central Otago. Scott visited the trial and wrote four short pieces. S. J. Franklin (Horticultural Advisory Officer, Alexandra) published two articles, one in Wine Review and one in the Journal of Agriculture. Scott’s characteristically provocative piece titled ‘Otago (2) High hopes meet official caution’ exposes the tensions he perceived between the official views of the Department of Agriculture and those of the local residents and politicians. Under the heading ‘Lukewarm Officialdom’ Scott’s angle was that:

Given an ounce of encouragement there will be no shortage of individuals ready to pioneer a Central Otago viticultural industry. Sharp frosts and searing summers, isolation and irrigation – these are no deterrent to the enthusiasts Wine Review spoke to on a recent visit.

The difference between the advice of the North Island scientists at the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station and the Central Otago advisory officer, Steve Franklin, is revealing. In May 1967, in answer to a written enquiry from an Otago resident interested in planting grapes, the representative of the research station replied:

Penfolds, I am told, looked at the South Island for wine production but settled on the North Island. My advice to you is to do likewise; or at least go into your venture with the knowledge that you may come across insuperable problems.

The local view was more informed and less extreme. For a start, Franklin showed more intimate knowledge of Central Otago’s sites:

Heat trap areas . . . are known to ripen stone fruit somewhat earlier than the average for the district. Such heat trap areas could be ideal for production of early to early-mid-season grape varieties. One has to live in Central Otago for several years, and spend time poking round the district, to get to know these spots or to realise their extent.

He added the following:

As vines do not normally come into growth before October only the last half of the frost fighting season would be a worry. In many seasons there would be no damaging frosts within this period, and in fact there were none in the season just past. Apples are at their most frost tender over the same period and it is not often necessary to light frost pots in an apple block.

Central Otago residents who knew the history of the region could also point to successful cultivation of the vine in the past. Even during the growing seasons of these debates, fruit from small parcels of vines in the region were being successfully ripened. As Scott implied, local winegrowers were likely to treat the debate as a challenge to prove the North Islanders wrong. Rolfe and Lois Mills of Rippon Vineyard certainly adopted this stance by planting a kaleidoscope of varieties before recognising that in their environment, a few kilometres from Wanaka, Pinot Noir performed best.

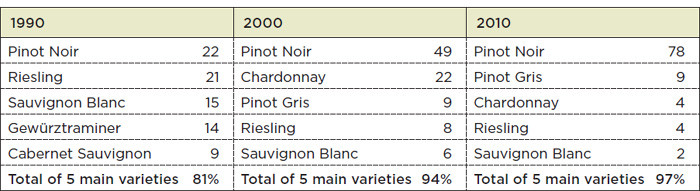

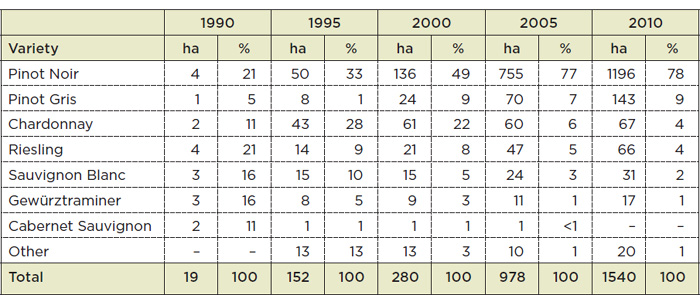

The mix of varieties in Central Otago has changed dramatically in the two decades from 1989 when the New Zealand Wine Institute collected the first reliable information on the varietal mix of regions. Pinot Noir has always been the dominant variety in this region. Its dominance has increased decade by decade and most noticeably in the twenty-first century. In 1990, Pinot Noir made up 22 per cent of the Central Otago vineyard; by 2000 it was 49 per cent; and by 2010 it was 78 per cent (Table 8.1). Marlborough, with 76 per cent of its vineyard planted in Sauvignon Blanc, is the only other region where a single variety is almost as dominant.

Two other varieties, Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc, have always been among the top five varieties in Central Otago during the last 20 years. Pinot Gris appeared as one of the five main varieties in the late 1990s and has since become the second most important variety, although, at just 9 per cent of the regional vineyard, well behind Pinot Noir. It looks destined to remain the second most-planted variety and the most important white variety for some time. Riesling is a possible challenger as several of the Central winemakers, including Blair Walters of Felton Road, are intensely interested in vinifying Riesling to achieve a wine of intense aromas and flavours but with low alcohol. In 2000, Chardonnay made up 22 per cent of the Central Otago vineyard but by 2010 it was just 4 per cent. It seems fated to remain a lesser variety except for those enterprises making sparkling wine.

Central Otago’s aspiring winegrowers stared down the scepticism of the ill-informed North Islanders by encouraging scientists to study the weather and climate of the region more thoroughly. Gordon Cossens, a scientist at MAFTech’s Invermay research station in Mosgiel, investigated the temperature regimes of this climatically complicated region and provided winegrowers with reliable information to supplement their empirical experiments. The outcome of these efforts was the creation of one of New Zealand’s most vibrant and exciting wine regions.

Horticulture, viticulture and Romeo Bragato

Horticulture and market gardening developed in Central Otago from the 1860s. Like similar mid-nineteenth-century gold-mining regions in California and Australia, small agricultural and horticultural enterprises sprang up to service the miners and their communities. In Otago the predominantly Anglo-Celtic population later used the abandoned water races, constructed for sluicing gold, to develop irrigated pip- and stone-fruit orchards growing predominantly apricots and cherries as the lowland foundations of the local rural economy.

Among the kaleidoscope of cultures attracted to Central Otago by gold was Jean Désiré Ferraud from France. On the west bank of the Clutha, just south of Alexandra, the name Frenchman’s Point records the spot where in 1863 he and a group of others struck it lucky. In 1864 he used the proceeds to purchase a property of 100 acres (41 hectares) near the mouth of the Waikerikeri Valley. Ferraud was elected the first mayor of the municipality of Dunstan (now Clyde) in 1866. By 1870 he and his family were growing over 1200 vines as well as a variety of fruits on ‘Monte Christo’. He sold this land in 1882 and moved to Dunedin where he became a partner in a firm that made wines and cordials.

Ferraud probably planted Pinot Noir. One of his wines, a ‘Burgundy’, won a merit award at Sydney in 1881. At that time the name Burgundy was more likely to mean the Pinot Noir grape, whereas in the resurgent wine industries of Australia and the United States of the 1960s the word Burgundy was used for wine from almost any red grapes. In the second half of the twentieth century, for instance, Gallo’s Hearty Burgundy was one of California’s most popular jug wines, but very little, if any, of it saw Pinot Noir grapes. Bragato almost certainly visited the former Ferraud property. In an 1893 photograph (two years before Bragato’s visit) vines were still growing against its stone winery. If the twentieth-century DSIR trial in Central Otago is taken as an example of survival without irrigation, other vines may also have survived on the Ferraud property. The trial was abandoned and the irrigation turned off in 1978 but its vines were still bearing fruit in 2002.

Table 8.1: Varietal evolution (% of Central Otago’s vineyard in five main varieties)

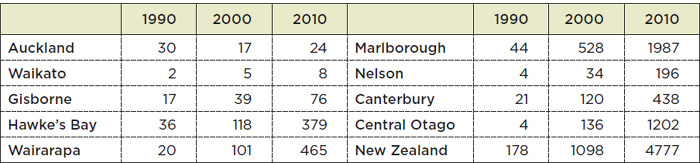

Table 8.2: Area in Pinot Noir by region (hectares)

Note By 2010, 220 hectares of Hawke’s Bay Pinot Noir and 167 hectares of Marlborough’s were used for sparkling wine. In 2000, Waipara grew 54 hectares of the total Canterbury Pinot Noir and by 2010, 313 hectares.

Early attempts at viticulture received approval when Croatian-born, Italian-trained scientist Romeo Bragato visited New Zealand. Bragato, Viticultural Expert to the Government of Victoria, Australia, arrived in New Zealand on 19 February 1895 under instructions from the Premier of Victoria, and at the invitation of the New Zealand government, to assess the prospects for viticulture in the colony. Central Otago was the first region he visited, commenting:

. . . the grapes, notwithstanding that the vines had been high trained, were perfectly ripe. This was on the 25th February, a convincing fact to me that the summer climatic conditions here are conducive to the early ripening of the fruit.

He did not identify the variety, but today’s grape growers would not be picking anywhere near this early in the season. Writing of the Queenstown area, he said:

In certain parts of this district, where a good aspect and well-sheltered spots are available, the cultivation of the vine may be undertaken, but judgment must be exercised in the selection of varieties to be planted, and cultivation and pruning methods must be adopted that meet the requirements of the colder vine-growing regions.

Other scientists were later to echo his caution.

By the end of the nineteenth century, therefore, Central Otago had shown its potential to ripen varieties of Vitis vinifera and make wine from them, but it took over 80 years before a prestige wine industry emerged. The successful cultivation of classical varieties of grapes and the making of wine in Central Otago during the 1860s and 1870s influenced this revival of viticulture a century later. Franklin mentions Jean Désiré Ferraud by name, while newspaper articles about the DSIR trial of the early 1970s quote an Italian viticulturist (undoubtedly Bragato) having said that the area was ‘pre-eminently suitable for the growing of wine grapes’ without mentioning his caveats.

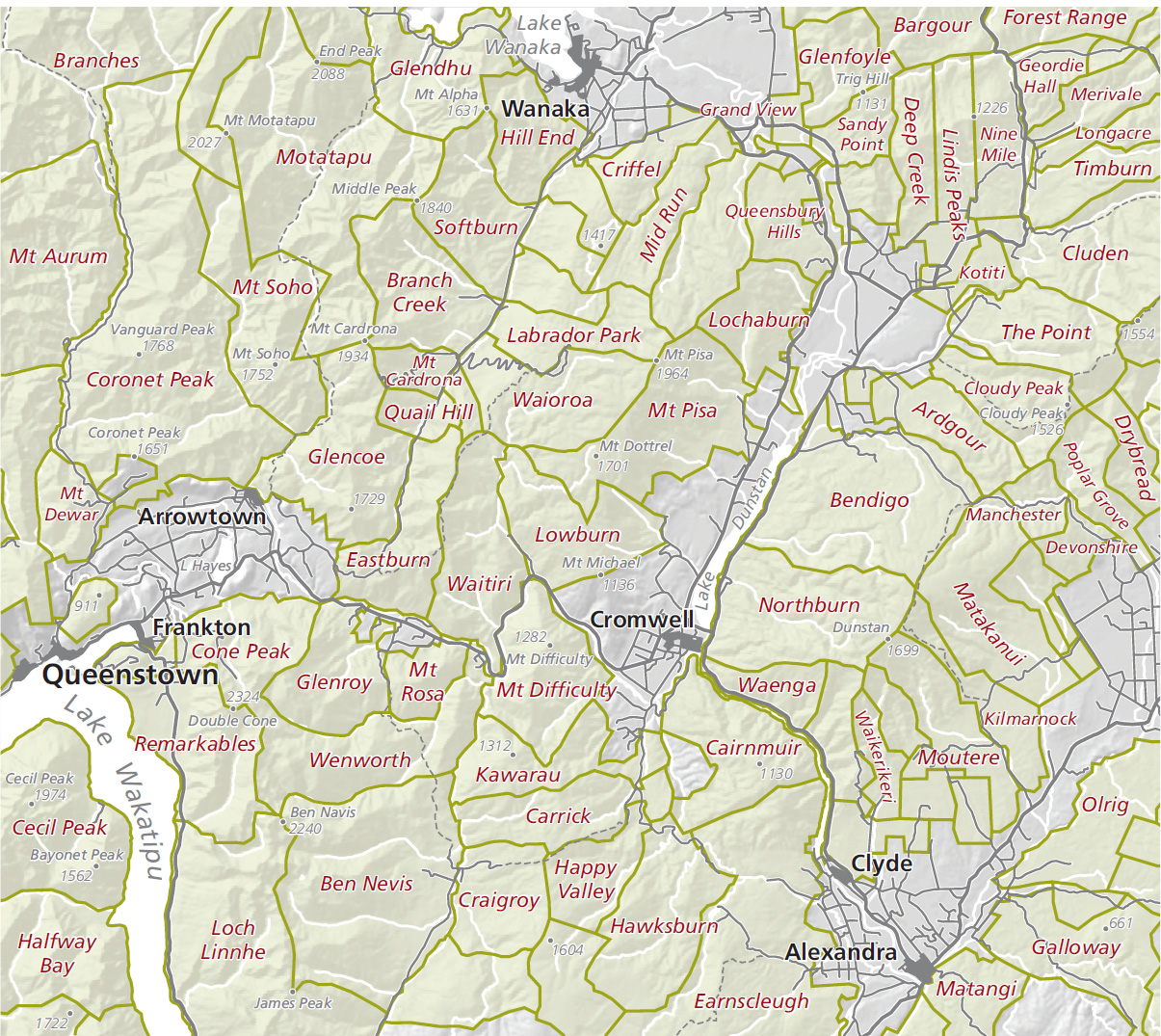

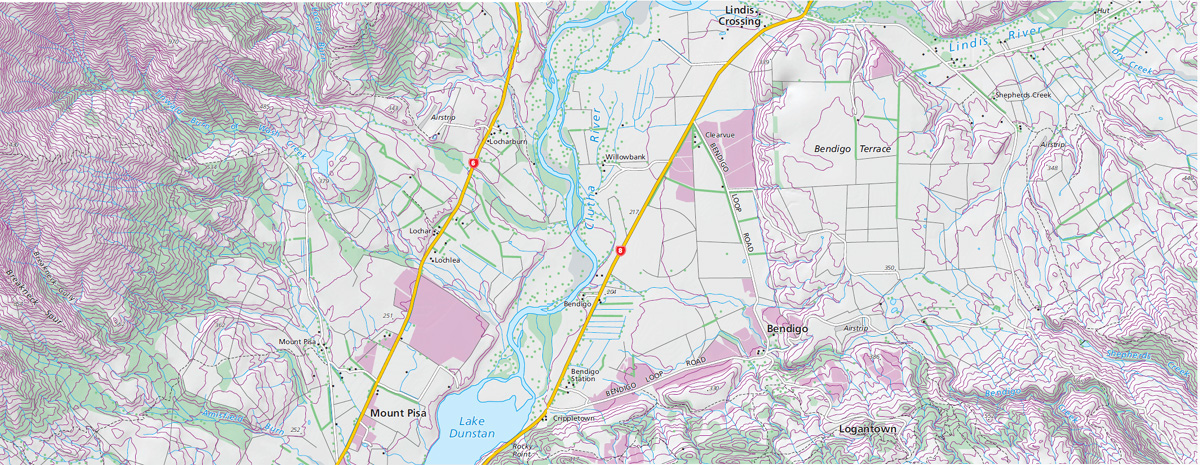

Central Otago’s terrain and sub-regions

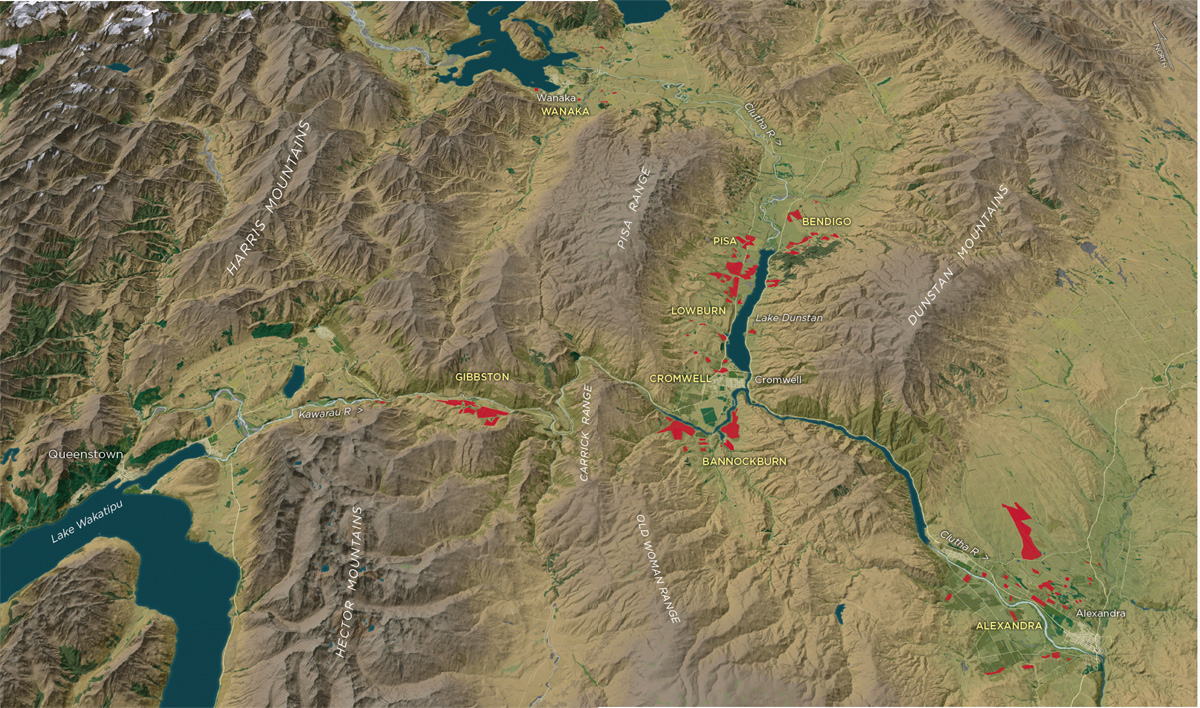

With its vines and wineries spread over an area four times larger than the Hawke’s Bay wine region and about twice as large as that of Marlborough, Central Otago is the most dispersed of New Zealand’s wine regions. Yet Central’s area in vines is about one third that of Hawke’s Bay and about 7 per cent that of Marlborough. Vines in Central Otago are clustered in what the local winegrowers call sub-regions, some of which are over 100 kilometres apart. Each sub-region has its own distinctive history, style, character and contribution to the story of the evolution of winegrowing here. As the wineries gradually acquire land in several sub-regions, their local distinctiveness erodes, although the quality of their wine may improve as they discover better sites for growing Pinot Noir. The six sub-regions commonly identified are: Wanaka; Gibbston and the Kawarau Valley; Luggate to Cromwell (Clutha and Lake Dunstan right bank); Tarras to Cromwell, including Bendigo (Clutha and Lake Dunstan left bank); Bannockburn; and Alexandra.

The terrain of Central Otago is aptly described as ‘basin and range’; valleys of varied widths are separated by substantial mountain ranges. The Clutha and Kawarau rivers and their tributaries provide the network to relate this terrain to the distribution of the region’s vineyards and wineries. The Clutha sets the north–south trend. From its source at Lake Wanaka it flows southeast for 20 kilometres before being joined by the Lindis River just before the first arm of the triangular Loop Road leading to the former mining town of Bendigo. The Clutha then carves south, the Pisa Range to its west and the Dunstan Mountains to its east. After the Kawarau River joins it at Cromwell the Clutha continues slightly east of south to Alexandra, the northern ridge of the Garvie Mountains to its west.

The Kawarau River has its source in Lake Wakatipu from where it sweeps eastwards around the northern fringe of the Remarkables, skirting the triangular tip of the Carrick Range before continuing eastwards to join the Clutha at Cromwell. This complex terrain, sculpted by these two rivers and their tributaries, results in slopes with many different aspects, parts of valleys that are shaded even during summer, and steeper slopes that in other countries are planted in vines (such as along the Rhine in Germany) but in Central Otago still grow tussock.

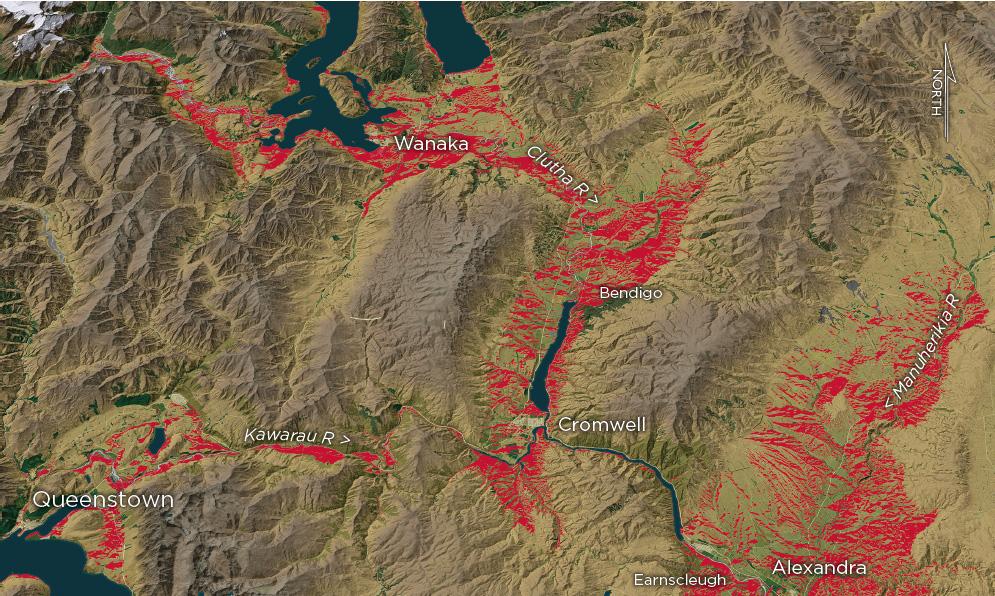

One way of revealing the relationships between vines and their terrain is to predict location of vineyards (and land with potential for planting them) by using measurements of the terrain that also strongly influence the weather and climate of the region. Three criteria are used in the digital terrain model that follows: elevation, slope, and aspect. Elevation has a direct effect on temperature. The decline in temperature with height (lapse rate) is about 1°C per 100 metres of elevation. The difference in elevation along the valley of the Clutha is small and the differences in temperature subdued. Between Lake Wanaka and Alexandra the change in elevation is only 100 metres. As a result the difference in temperature between the two locations directly attributable to elevation is about 1°C, although many other influences, notably aspect, affect the climates of individual sites.

In contrast, changes in temperature as a result of elevation are spectacular over short distances between valleys of the Clutha and Kawarau and the adjacent hills and mountains. Differences in elevation of 500 to 1000 metres between the floor of a valley and the nearest major ridge are common. As a result, daytime temperature differences of between 5°C and 10°C over a few kilometres are also common. Elevation has a major influence on precipitation and wind. Being in the rain shadow of the Southern Alps, most of Central Otago receives under 600 millimetres of precipitation annually. Irrigation is essential here. Gordon Cossens’ work also established that in terrain such as that of Central Otago the lapse rate varies from between 0.3°C to the widely quoted 1°C.

Slope also influences the potential for winegrowing. Slopes of over 15 degrees make mechanical cultivation difficult. Central Otago’s western hills and mountains are much steeper than those further east. The Remarkables, and further north the Crown Range and mountains west of the Cardrona River, have very few slopes less than 15 degrees. To the east, the Pisa and Dunstan ranges have been smoothed by glacial action, and a much higher proportion of their slopes are less than 15 degrees, especially their north- and west-facing ones. Nevertheless, the majority of gently sloping land suitable for vines under present climate conditions is in the river valleys, or very close to them. The main hazard along these valleys is spring frosts from cool-air drainage onto flat land. Winegrowers have often chosen adjacent slopes to avoid this hazard.

Figure 8.1 Altitude, slope, and aspect as environmental constraints on viticulture in Central Otago. The map identifies land with elevation of less than 400 metres, a slope of less than 15 degrees, and a northwest through northeast aspect.

When it comes to aspect, a distinction again exists between the western and eastern parts of the Central Otago wine region. Those localities where vineyards are dense – the Gibbston locality along the Kawarau, the Clutha–Lake Dunstan valley (including Bendigo), Bannockburn and Alexandra – all have a high proportion of northerly facing slopes. Again, the valleys of the Cardrona and Nevis rivers establish a clear boundary between the northwestern, triangular third of Central Otago where northerly facing slopes are scattered and scarce, and the remaining two thirds of the region. East of the Cardrona–Nevis line, vines are much more dominant in the landscape.

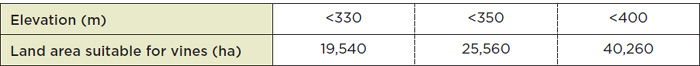

When elevation, slope and aspect are combined on one map, the potential land for vineyards in Central Otago is defined (Figure 8.1). This map identifies almost all the places where some vines are already planted; it also indicates the parts of the region that are likely to attract attention for future plantings. Even when a strict limit is put on elevation by considering land only under 330 metres, almost 20,000 hectares is classified as being suitable for vines (Table 8.1). Easing this elevation restraint to less than 400 metres doubles this figure to 40,000 hectares. In 2010, New Zealand’s total area in vines was 33,428 hectares and Central Otago’s about 1500 hectares. It thus seems highly unlikely that Central Otago will run out of vineyard land in the immediate future.

Table 8.3: Terrain (and associated climate) influences on vine sites in Central Otago

Note The calculations are based on three criteria: elevation; slopes of <15 degrees; and an aspect of northwest through northeast. For this table, only the elevation is allowed to vary.

On the north- and west-facing slopes of the higher terraces at Bendigo, Pinot Noir has been planted as high as 400 metres. It ripens here because the favourable aspect of these slopes increases annual solar energy by up to 120 degree-days annually and offsets their higher altitude. Chinamans Terrace, as it is known locally, is a kilometre from Rudi Bauer’s original Bendigo plantings on the southern arm of the Loop Road and the same distance from the Perriam homestead of Bendigo Station. South towards Cromwell along State Highway 8, the aspect of the Lakeside Vineyards is more westerly. Here, a variety of owners have intensively planted from almost on the lakeshore to about 400 metres. They include Misha’s vineyard and Devil’s Creek. Many other favourable sites at similar altitude exist in the region.

The most surprising results from this digital terrain model are the large areas of land suitable for viticulture in the Manuherikia catchment. When combined with the well-established orchards and other smallholdings along the Earnscleugh and Alexandra–Fruitlands Road, this southeastern corner of Central Otago contributes well over half the 20,000 hectares of land below 330 metres identified as being suitable for vines. The Earnscleugh and Fruitlands roads have a long history of successful intensive horticulture by orcharding enterprises, and viticulture has made only small inroads there. Farms practising pastoral agriculture in the Manuherikia and adjacent smaller catchments are more likely to be subdivided for vines than those holdings already successfully growing other horticultural crops.

The north- and west-facing slopes of the Bendigo Terraces provide a sun trap that enables winegrowers to plant as high as 400 metres above the Loop Road. Alan Kwok Lun Cheung

Central Otago also has the advantage of much cultivable land at higher elevations not planted in vines. These higher slopes are likely to become more important in the future. At present many of them are not warm enough to ripen the available clones of Pinot Noir. Two things are likely to change this: new clones of Pinot Noir and global warming. Scientists in the research establishments of several countries are attempting to breed cultivars of Pinot Noir that will mature in a shorter growing season. When these are available, sites now viewed as marginal will be re-evaluated. Global warming will further enhance the attraction of these higher sites because Central Otago viticulturists will be able to use planting at higher altitude to ameliorate its effects. Both factors will increase Central Otago’s area in land suited to viticulture.

Even without such environmental and technical changes, the land suitable for planting vines, notably Pinot Noir, is considerable. Constraints of climate and terrain are not the main restriction to increasing the area in vines in Central Otago. Access to suitable sites is likely to be more limiting. Many of them are at higher elevations and part of viable, although extensive, livestock farming operations. It will require landowners to make these sites available or plant them in vines.

In the round of planting on greenfield sites from the mid-1990s into the new millennium the economic rent (return on investment) to be gained from winegrowing was sufficient to encourage runholders to free up land. Windfall gains of $15,000 per hectare from land sold for viticulture in localities such as Bendigo were difficult to resist when the market for fine wools from merino sheep was faltering. Whether demand for Central Otago wine will continue to grow at a similar rate is difficult to predict hard on the heels of a set of economic uncertainties in the first decade of the twenty-first century. But the international market for wines of high quality and reputation from exotic, beautiful places will continue to increase. Central Otago’s vines and wine landscapes enhance its attractiveness to tourists and to the international market for its wine.

Viticultural trials

Central Otago, like other regions of New Zealand praised by Bragato, saw few grapes planted until the late 1970s. The stirrings of the table wine industry in Hawke’s Bay, Auckland, and its extension into Gisborne during the 1960s aroused local and scientific interest in many parts of New Zealand including Central Otago. The region’s reputation for orcharding led two departments of central government – the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research – to establish grapevine trials starting in 1962. The interest in grape growing was stimulated by government’s rural policy, which offered generous tax breaks and low-interest loans for intensifying rural production, and the horticultural euphoria sparked by kiwifruit that swept the rural economy.

The objectives of the two trials were different. The Department of Agriculture one was to test the ‘hardiness’ of varieties in a region such as Central Otago, and the DSIR one to test varieties known to be suitable for unfortified table wines. A summary of the varieties of vines grown in the Department of Agriculture trial run from 1962 to 1973 and the DSIR trial that ran from 1972 to 1978 illustrates the sea change that was beginning to emerge in New Zealand viticulture. The hybrids (especially the Seibels), bulk producers such as the Muscats and Müller Thurgau, and the sherry grape Palomino dominated the Department of Agriculture trial. These were the foundation of New Zealand’s fortified wines and continued to be important in the ‘bag-in-box’ wines of the 1970s and 1980s because by then the vines of these varieties were mature and bearing heavy crops in Auckland, Gisborne and Hawke’s Bay. However, it does show that the South Island and Central Otago were on the Department of Agriculture’s viticultural radar a decade before Montana’s move into Marlborough in 1973.

The DSIR trial of the 1970s had a quite different suite of varieties. It concentrated on the vinifera wine varieties and clones that dominate the cooler regions of France and Germany. Some of these, especially Chardonnay and Riesling, had begun to show their potential in twentieth-century New Zealand during the 1960s. Others were yet to perform. The plantings (with their main French regions of origin in brackets) included Pinot Noir and Chardonnay (Burgundy), these two plus Pinot Meunier (Champagne), Gewürztraminer and Riesling (Alsace), as well as Gamay (Beaujolais), Cabernet Sauvignon (Bordeaux) and Syrah (Rhone Valley). Also included were a few of the hybrids and recently bred German varieties such as Stein. Pinot Gris had been planted in the earlier Department of Agriculture trial.

Results from these trials encouraged both the pioneering growers, some of whom took cuttings from the vines, and those who organised the experiments. But the fuller incorporation of their stories into the folklore of the region had to await the development of the late twentieth-century wine industry in Central. Once commercial production was established, producers, consumers, publicists and journalists reinvoked and re-established these histories and extended the association of the region with the vine back to Ferraud and Bragato.

Pioneers of the modern industry

By the early 1980s, five growers had established vineyards in Central Otago. They were Alan Brady, founder of Gibbston Valley Wines; Verdun Burgess and Sue Edwards of Black Ridge; the Grant family of William Hill Vineyards; Rolfe and Lois Mills of Rippon Vineyard west of Wanaka; and Ann Pinckney of Taramea Wines. Pinckney was the first to establish a winery, on the Speargrass Flat east of Queenstown, and several of the other enterprises made their first wines there. This group’s motto was to ‘plant and to hell with it’.

Rippon Vineyard became something of a viticultural trial in its own right and Rolfe Mills a willing source of knowledge to potential growers. ‘If MAF or anybody else said it wouldn’t grow here, I’d plant a few vines,’ he declared. Rolfe and Lois Mills first planted the hybrid Seibels in 1974, to which they added Albany Surprise in 1975, with the bulk of the vineyard being planted in 30 varieties in 1981. New clones of Pinot Noir were added in 1985.

The Grants of Alexandra experimented with a few vines a decade before Rippon. Bill (William Hill) Grant, a schoolteacher at the time, planted about a hundred cuttings of the table grapes Gros Colman and Black Hamburg shortly after buying property near Alexandra in 1962. They were killed by a heavy copper spray. His 1974 cuttings and nursery of Chasselas and Palomino came from the Department of Agriculture trial on the Kinnaird property. Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Gewürztraminer and Müller Thurgau vines from Blenheim were added in 1979. The William Hill vineyard remained smaller than Rippon until the Grants, with son David now in the business, purchased a mobile bottling plant. This attempt to diversify their enterprise became difficult to sustain in the economic conditions of the early twenty-first century and the family firm filed for bankruptcy in 2009.

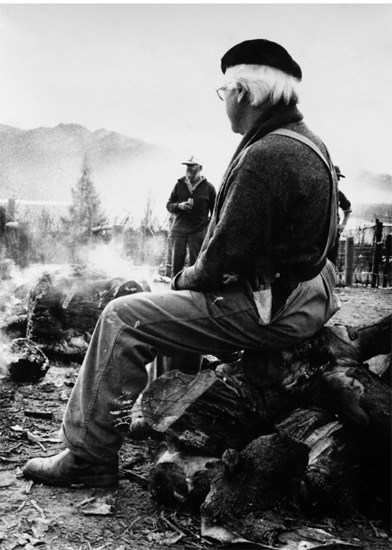

The bereted bon vivant Rolfe Mills of Rippon Vineyard was one of a small group of Central Otago enthusiasts who built a wine industry out of nothing. Rippon

Both the Grant and the Mills enterprises were initially relatively indiscriminate about the varieties they planted, taking a decade or more to establish their preferred varieties. In one sense, this hesitation was surprising, because by the early 1970s the classical varieties of Vitis vinifera were beginning to show their superiority in the North Island regions. Moreover, Central’s DSIR trial of 1972–78 included all of the vinifera varieties that were to prove successful in the region, including both Pinot Noir and Riesling. On the other hand, both William Hill and Rippon were initially hobby vineyards, remote from other commercial vineyards and wineries and the year-to-year accumulation of knowledge that was more characteristic of West Auckland, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and even Marlborough at the time.

Ann Pinckney, who had met Professor Helmut Becker of the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute when he visited New Zealand in 1978, also favoured the Germanic varieties in her first plantings (she ‘met Gewürztraminer’ during a six-week stint in Alsace), and with Dr Rainer Eschenbruch of the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station undoubtedly influenced her Speargrass Flat neighbour Alan Brady. Brady initially tried a small number of varieties without knowing how they might perform on his Gibbston property. In 1981 he planted 100 cuttings each of Pinot Gris, Gewürztraminer, Müller Thurgau and Chasselas. When he had mixed success, partly because of inexperience, he took the advice of Eschenbruch and planted the Germanic variety of the moment, Müller Thurgau. Within a year, after increasing contact with Rolfe Mills and Ann Pinckney, he had replaced the Müller Thurgau with 3000 Riesling plants and 4000 Pinot Noir. In these 1984 plantings he also experimented with Pinotage and Cabernet Sauvignon. Empirical experience soon showed him that neither was suited to Central Otago: ‘The Pinotage never ripened. But it looked wonderful – big, healthy-looking bunches. It was as green as anything with very high acid. It wasn’t any good.’

Three observations stand out from the Brady chronology: he was willing to experiment; he was temporarily attracted to (or advised to plant) the popular varieties of the moment; and he rapidly adjusted to plant varieties that were proving successful in Central Otago. Within four years of his first planting he had settled on Pinot Noir and Riesling as the two main varieties at Gibbston Valley Wines, supplemented by Pinot Gris and Gewürztraminer from his original plantings. It is unlikely that the transition would have been as quick if similar learning had not already occurred among several of the other pioneering growers. These four varieties are among the principal varieties of the elite wine regions of northern France and southern Germany – Burgundy, Champagne and Alsace.

The serendipity of dispersed plantings

The efforts of these first five enterprises to plant a significant area in grapes illustrated key features that were important to learning about the suitability of natural environments of the Central Otago region for different varieties of Vitis vinifera: they made production rather than location decisions; they were dispersed but interacted closely; they were liberal in passing on their knowledge; and they possessed a mixture of talents.

All the first five growers owned their land and decided to plant grapes on it rather than searching more widely for suitable sites. From the point of view of adding to the store of knowledge of Central Otago’s viticultural environments, their dispersal proved enlightening. The five were sufficiently spread (Wanaka; Alexandra and the Earnscleugh Road; Gibbston in the Kawarau Gorge; and Speargrass Flat) that the north–south extent of the localities suitable for vines, and a large part of the east–west extent, were clarified by their success or failure with different grape varieties. This dispersal, together with the interaction among the owners, built the initial spatial knowledge of Central Otago’s natural environments. Rolfe Mills, Ann Pinckney and Alan Brady met regularly. They made wine in the Taramea winery on Pinckney’s property on Speargrass Road and were the forerunners of the Central Otago Winegrowers Association.

Three of the currently important clusters of vineyards and wineries – the Gibbston locality in the Kawarau Gorge (often now loosely referred to as Gibbston Valley after its first winery), Alexandra (William Hill Vineyards), and the schists along Earnscleugh Road (Black Ridge) – have all become successful localities for vines. By the mid-1990s some of the local grape growers, now with considerable experience of different parts of the region, such as Michael and James Moffitt (the sons of Bill and Sybilla Moffitt of Dry Gully Vineyard) and actor Sam Neill, had bought land and planted on the northeast-facing ridge of schists.

Despite the Wanaka area having its well-known Rippon Vineyard and winery, this locality has so far seen only small areas planted in grapes. Much of the land surrounding Rippon is steep and difficult to cultivate. Moreover, Rolfe and Lois Mills had first choice of land in the vicinity. Subsequently, owners of high-country runs were reluctant to sell small parcels of land, especially when the price of land was rapidly increasing. The area of Speargrass Flat (Taramea Wines) has also seen few vines planted. Growing grapes over several seasons helped Ann Pinckney to establish empirically the patterns of one of the main hazards to viticulture in this part of the region. Her experience in fighting frost on her own property and in establishing vines on her mother’s nearby land helped establish the low probabilities of success there (Ann was initially reluctant to use smudge pots for frost control anyway because in her other life as a Karitane nurse she did not want to have soot fall on the nappies drying on the clotheslines of the Speargrass Flat).

Four aspects of the Central Otago experience inform the general story of the importance of learning in the regional specialisation of New Zealand winegrowing. First, empirical experimentation by growers on specific sites was the initial means of establishing the suitability of parts of the region for particular varieties of vines and the quality of wine that could be made from them. Second, winemakers working for the first few wineries extended this spatial knowledge by processing grapes from other sites. Taramea was the first of these wineries. Once Gibbston Valley Wines had established their own fermentation facilities in the Kawarau Gorge they began processing grapes on contract or buying them from vineyards in other localities. Their knowledge of the other localities in Central Otago soon widened, placing them in a much stronger position to choose where they would source their grapes from, to obtain qualities of flavour and aroma to enhance the wines made from their existing sites. By 2010, Gibbston Valley Wines owned about 10 hectares in the Gibbston locality but sourced grapes from over 60 hectares elsewhere in Central Otago, some on land they had purchased and some bought from grape growers.

The Gibbston Valley looking west towards Lake Hayes and Queenstown. Alan Kwok Lun Cheung

Third, this filière structure – grape growers (often aspiring winegrowers) with small areas in vines selling to the few wineries or having wine made by them under contract – was secured through local capital establishing the Central Otago Wine Company. This is a contract winemaking company in Cromwell partly funded by actor Sam Neill that makes wine for different labels from vineyards scattered throughout the region. From harvest to bottling and beyond, its principal winemakers (Mike Wolter followed by Dean Shaw) became repositories of knowledge of the qualities of the region’s wines, especially of the dominant variety Pinot Noir and its variations from many vintages and across a wide range of sites. This knowledge filtered through to other participants in the industry.

Fourth, the distinctive filière of this region was reinforced by the organisation of particular enterprises. Until the early twenty-first century, Peregrine Wines sourced almost all of its grapes from its own contract growers. These are not contract growers in the sense in which the term is used in other regions – that is, farmers who already own land and plant grapes on part of their property. Many of the Central Otago growers are New Zealand or international professionals who either purchased their land and house site from Wentworth Estates, the associated company that subdivided and marketed the Gibbston lowland portion of Wentworth Station, or took advice on purchasing other land from Greg Hay of Peregrine or other informed locals. Purchase of the 4-hectare sites from Wentworth initially included the contracting of the planted grape crop back to Peregrine who also tended such vineyards. The distinctive blue Peregrine vineyard sign designating their contract growers has dotted the landscape of Central Otago from Gibbston to the side roads of Lowburn, and from Bendigo to Northburn Station. Peregrine was marking out its territory just as Cloudy Bay signposted its Marlborough vineyards when it was first established.

Central Otago’s vine climates

The decision in the 1970s to dam the Clutha River and build a hydroelectric power station near Clyde was highly controversial. Sluicing for alluvial gold from the 1860s, followed by dredging for gold in the twentieth century, had already degraded the lowland landscape of much of Central Otago. Locals were polarised by the prospect of their unique landscape and close communities being split and divided by a 50-kilometre lake from the dam at Clyde to the Loop Road, Bendigo. Construction finally commenced in 1982, the dam was commissioned in 1992, and Lake Dunstan filled in 1993. At the junction of the Clutha and Kawarau rivers the lake flooded the lowest and oldest part of the historic mining town of Cromwell. It also affected the narrow Kawarau Gorge that links Cromwell with Arrowtown and Queenstown.

The National government of the 1970s and early 1980s and the Labour government from 1984 placated Central Otago’s rural population by providing funds for a joint study by the Ministries of Agriculture and of Works to investigate the possibilities of intensifying the rural production of Central Otago. Scientists in the regional offices of these two central government agencies focused on establishing the temperature and wind patterns along the upper Clutha and Kawarau rivers. Grapes were included as one of the main crops to be considered, although the weather and climate information which was compiled could be applied to a variety of annual and perennial crops. MAFTech’s Gordon Cossens organised much of the data collection and analysis and was lead author on most of the reports.

This detailed scientific work was disseminated in a series of publications that were printed sub-region by sub-region as the research was completed. Those contemplating winegrowing in Central Otago, including local landowners, devoured the information. The strength of the research derives from the close network (‘swarm’ in the climatological jargon) of temporary climate stations the researchers established in each sub-region. The fine resolution of the network, when integrated with the longer climatic record of the meteorological stations of Central Otago, established the seasonal temperature regimes and wind patterns of the localities where grapes might be grown. The topoclimatological studies identified potential vineyard sites in new localities – notably in the Lowburn area, on both sides of Lake Dunstan, near Bendigo, as well as at Bannockburn and the higher terraces along Lake Dunstan. No other wine region in New Zealand had such a comprehensive analysis of its weather and climate.

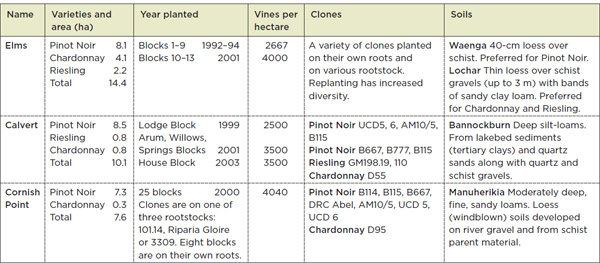

By the early to mid-1980s, empirical knowledge of the performance of different grape varieties was accumulating rapidly among the first group of wine enterprises and could be generalised and verified against the detailed information from the data collected by Cossens and others. By the early 1990s, the second wave of aspiring winegrowers such as Stewart Elms, the Dicey family and Steve Green of Carrick were able to differentiate the climates of different parts of Central Otago and be more confident in their choices of where to buy land and plant.

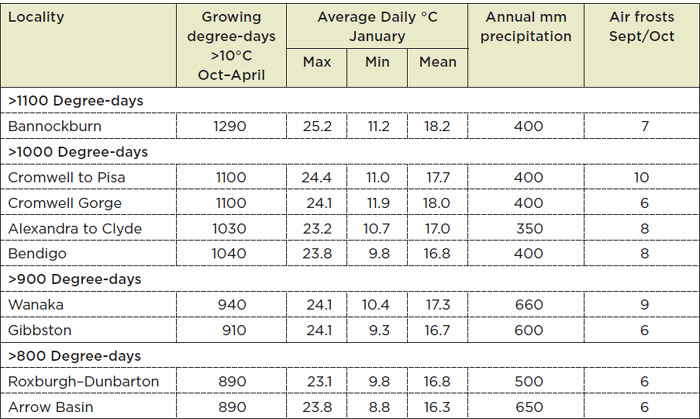

Table 8.4: Favoured locations for possible Central Otago vineyards

Cossens’ research demonstrated that the accumulation of energy over the growing season varies considerably from one locality of Central Otago to another (Table 8.4). Two of the three places where grapes were already planted (Gibbston and Wanaka) both accumulate fewer than 950 degree-days over the growing season, whereas Alexandra (1030) and Bendigo (1040) receive appreciably more solar energy. The results from Bannockburn are even more persuasive. Its degree-days during the growing season are at least 350 higher than Wanaka and Gibbston and more than 150 higher than all other districts. The conclusion is clear: the first plantings in Central Otago were not in the most favourable places for coaxing grapes to reach physiological maturity.

One caveat needs noting. The low night temperatures of Gibbston and Wanaka are the main influence on reducing their average temperatures. Daily highs are much more similar across all of these sites. The same is true of Bendigo. Such high diurnal ranges of temperature encourage the development of flavour compounds as the berries of Pinot Noir ripen. Nevertheless, the differences in day/night temperatures of these first vineyards is not sufficient to change the general conclusion that other parts of Central Otago had climatic advantages over Gibbston and Wanaka for growing grapes. However, any environmental disadvantages became less significant as the Central Otago wine region matured. Wineries in the Kawarau Gorge could diversify their sources of grapes by buying or growing them in sub-regions such as Bendigo or Bannockburn where the probabilities of ripening grapes every year are higher. Moreover, Gibbston and Wanaka had other advantages that compensated for their climatic limitations. In both summer and winter, vehicle traffic counts are much higher through these localities than other rural parts of Central Otago. Wineries in the Kawarau Gorge benefit hugely in both their tasting rooms and restaurants from direct sales to this passing traffic.

The Cossens publications became available between 1985 and 1990 when the interest in planting vines was about to take off. From about 1995, when fewer than 50 hectares were planted, the area in vines in Central Otago increased sharply (Table 8.5). By 2000 it had reached 280 hectares and by 2005 this had more than tripled to 978 hectares. By 2010 it was 1540 hectares with Pinot Noir making up 78 per cent of the total area in vines. During this rapid expansion, Pinot Noir vineyards appeared on a much wider range of sites. Cossens’ work had alerted many of the new and established grape growers to the environmental advantages of these alternative sites. They were able to make more informed choices on where to plant Pinot Noir. New vineyards appeared on the western side of Lake Dunstan in localities from Queensbury to the outskirts of Cromwell. On the eastern side of the lake, Ardgour, Bendigo Station (the Loop Road and the Terraces) as well as Cairnmuir and Bannockburn have all become important concentrations of vines.

The following extracts typify the clear and realistic advice Cossens provided for existing and aspiring grape growers:

Table 8.5: Grape varieties in the Central Otago region, 1990–2010

. . . the development of a wine industry south of the Waitaki will be confined to those localities which are within a few kilometres of the 45th parallel and below 400m altitude.

The most favoured localities, very suitable for cool climate wine production, are the semi arid brown-grey earth soils at Bannockburn, those from Cromwell to Pisa and about Alexandra to Clyde. All have mean January temperatures of 17°C or higher and 1000 to 1250 GDD [growing degree-days] in degrees Celsius October to April.

The thermal conditions at any of the above locations can be enhanced by shelter, slope, and aspect. Shelter adds some 100 GDD. On the other hand, each additional metre in height loses about one GDD but increasing altitude can make sites less frost prone in the critical September to November period.

The risk of frost is always present so site selection is of prime importance in reducing this. Sites should preferably be sloping . . . slightly elevated above the intermediary terrace and away from the areas of severe cold-air ponding.

The daily mean maximum humidity is about 88% (roughly 9.00am), the minimum 53% (roughly 3.00pm). Absolute minimum humidities can be as low as 10%, but less than 30% is not uncommon for September through March.

Within all localities are high terraces which, on the data available, would appear to be suitable for vineyards having particularly the necessary vineyard soil characteristics. The thermal regime, indicated by the mapping, was warmer than anticipated. However . . . the terraces are exposed to the wind and lack shelter.

To mature grapes satisfactorily vineyards should be no more than 80m above the lower terrace of the Clutha or Kawarau Rivers and not more than 400m altitude above sea level. All sites above 400m should be viewed with great caution.

In spring frost kill depends on whether buds are wet or dry. Critical temperatures for dry sprouts in spring are -1.5 to -2.0°C (air temperatures), for wet sprouts it is as warm as -0.5°C.

Accumulation and sharing of knowledge

Nigel Greening’s search for a suitable site in the late 1990s demonstrates how he conducted his own investigation before plucking up courage to approach the high priests of Central Otago winemaking:

Then as I learned my wines I started talking to people. I found the soil maps and started studying those. And then I got the topographic maps and started marking every slope that went the right way on the maps. I got a four-wheel drive and started driving. And I did that for about four or five months. . . . So I plucked up courage and knocked on Rudi Bauer’s [Quartz Reef] door. He was very supportive, He said, ‘Well, all your homework is good.’ He said I ought to go and knock on Alan Brady’s door [Gibbston Valley], which I did. . . . So I then went into phase two where I steadily narrowed it down to 30 sites then got it down to about twenty. Alan looked at about ten of them with me.

Nigel Greening bought the apricot orchard on Cornish Point before later buying Felton Road.

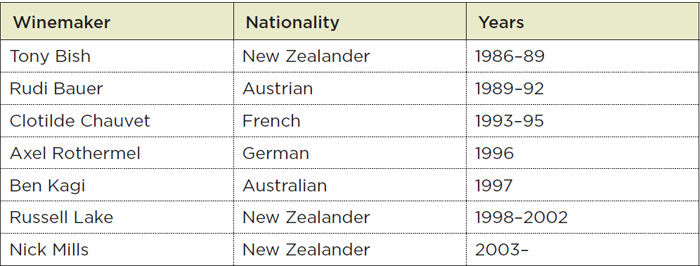

Numerous other new enterprises have emerged through experienced personnel leaving established ones and starting their own. Rob Hay who launched Chard Farm in the late 1980s was winemaker for Gibbston Valley while Chard Farm was being established. Greg Hay, Rob’s brother, was running the viticulture for Chard Farm before he became involved in the Wentworth development and Peregrine. His influence there built on his previous experience, including knowledge of the quality of grapes from Gibbston sites compared with others in the region. The list of winemakers for Rippon Vineyard (Table 8.6) includes Rudi Bauer and Clotilde Chauvet, both of whom later returned to Central Otago and for twelve years were in partnership making Méthode Traditionnelle at Quartz Reef.

Alan Brady began his small Mount Edward winery in 1998 after he sold most of his shareholding in Gibbston Valley to Mike Stone, the American casino owner based in Wanaka. Steve Davies returned to New Zealand in 1999 after experience in California, initially to be winemaker for the recently formed Akarua in Bannockburn shortly after Sir Clifford Skeggs established it as one of the largest continuous areas in vines in the region. Davies then became winemaker for the Carrick winery, almost directly opposite on the Bannockburn Road and owned by Steve Green, the former chief executive of the Otago Regional Council and collaborator with Robin Dicey before Mt Difficulty was established.

The Annual Report of New Zealand Winegrowers lists all the country’s wineries in three categories: those producing over 4 million litres of wine annually (large wineries); those producing between 200,000 litres and 4 million litres (medium); and those producing less than 200,000 litres annually (small). These lists of wineries and grape growers make it possible to establish the scale of production in the Central Otago region. In 2010, just four wineries – Amisfield Wine Company, Chard Farm, Mt Difficulty and Peregrine Wines – were in the medium category of wineries. Central Otago’s remaining 98 wineries each produced fewer than 200,000 litres of wine annually, many much less than this. With 1540 hectares of vines in production in 2010, the average area of grapes per winery in Central was 15.1 hectares. On average, therefore, they had about the same area in vines as family operations in the prestigious appellations of the Côte d’Or, Burgundy. For those wine enthusiasts wishing to visit a region where most wineries are small, and owned and operated by families, Central Otago is the ideal choice.

Moreover, very few enterprises in Central Otago declare themselves as grape growers. In the 2010 New Zealand Winegrowers Annual Report only eleven Central Otago enterprises are listed as grape growers. This figure gives the region the lowest proportion of grape growers to wineries of any major winegrowing region in New Zealand. It also suggests that almost 90 per cent of the enterprises involved in winegrowing consider themselves as wineries because they make wine commercially, even though they may not yet have their own winery. This situation is likely to change. Localities within Central Otago such as the Kawarau Gorge and Bannockburn already have sufficiently dense clusters of wineries to attract substantial numbers of New Zealand and international tourists. As the number of successful wineries increases, the demand for grapes grown locally will follow. Verbal or written contracts with the small number of local growers are already zealously guarded.

Fine wines and fine wools

Fine wines are woven into the story of fine wools. The homesteads of high-country runs (stations) nestle into sheltered spots along the basins of Central Otago (Figure 8.2). These pockets of easier-sloping, sometimes irrigated land are the most productive on these properties and were often planted in lucerne or other crops. Parts of many are now in vines. Owners or traders of the traditional, large, family-owned pastoral farms of the South Island have entered grape growing or the development and selling of their land for vines. The owners of Northburn Station, one branch of the Pinckney family, first grew grapes for Peregrine. After developing their own successful vineyard in consultation with Greg Hay they then subdivided land along their road frontage on the eastern shores of Lake Dunstan and sold these parcels as vineyard land. They have also successfully diversified the sources of income from their own high-country run. Ten kilometres further north, owners of the numerous vineyard sites formerly part of Bendigo Station – of ‘Shrek’ the unshorn merino wether fame, owned by John and Heather Perriam – include Gibbston Valley and Quartz Reef as well as the Perriams and many other growers.

Figure 8.2 High-country runs of Central Otago

In 2008 the Central Otago Winegrowers Association published a map showing 42 wineries in their region. Just like the homesteads of the high-country runs, the wineries have clustered mainly in the accessible valleys and lowlands of the region. The settlement of Gibbston and the valley of the Kawarau River offer the best example. From the imposing Nevis Bluff in the east almost to Lake Hayes in the west, five high-country runs had their boundaries along the Kawarau River. From the south, three runs – Wentworth, Mount Rosa and Glenroy – fronted the Kawarau River and the parcels of freehold land along it. From the north, the two runs of Waitiri and Eastburn do the same. These former gold-mining localities have a rich history. Wine enterprises have mined this history by appropriating the names of sheep runs, settlements and features of the natural landscape. Mt Difficulty, Gibbston Valley Wines, Waitiri Creek, Mt Rosa and Coal Pit are all examples.

Maps of the vineyards and wineries of Central Otago, alone or combined, cannot yet capture the spatial organisation of the winegrowing enterprises of this region. Some wineries are still located in the industrial area of Cromwell, the settlement that housed most of the workers when the Clyde dam was being built. When the workforce left in the early 1990s, surplus industrial buildings in Cromwell were a windfall for many wine and other enterprises. They could rent or buy them at reasonable cost and concentrate on developing their vineyards while gradually purchasing winery tanks and equipment. Some new wineries, such as Rockburn, have since been built on sites in Cromwell. Resource consents for drainage and other essential requirements are often easier to obtain in such well-serviced industrial estates than for greenfield sites in the countryside.

Enterprises in the Central Otago story

Rippon Vineyard

Rolfe Mills was a scion of the Sargood family of clothiers. From 1912 to 1940, Percy Sargood ran the firm’s South Island operation out of Dunedin. He also owned over 46,000 acres of high country that included the Wanaka Station. This land was sold when Sir Percy died, although one of his daughters managed to buy back about 3000 acres of it. It was here, on the shores of Lake Wanaka, that Rolfe Mills spent many of his childhood summer holidays.

The Sargoods’ primary business was textiles, clothing and footwear. Rolfe was managing their South Island operations from Christchurch when in 1973 the company merged with a similar firm, Bing Harris. He took this opportunity to leave the trade and build a house clad with mud bricks on 85 hectares of the family land west of Wanaka. With his wife Lois, and two young children Sarah and Nick (soon to be three when a second daughter Charlie was born), the family settled in rural Central Otago. They started Rippon Farm in 1973, the same year that Frank Yukich of Montana planted vines in Marlborough.

Living on the spectacular Rippon site was Lois and Rolfe’s primary attraction to the land but they were also committed to using it productively. They were torn between breeding and grazing goats and planting vines. Rolfe initially knew more about wines than he did about vines. He had visited some of the renowned wine regions of Europe, notably Portugal, where he was intrigued by the similarities between the schist soils of the Oporto region and those of Central Otago. He was also intent on finding out which varieties of grapes would grow on their Wanaka land. Their first vines were planted in 1974. By 1981 they had about 2 hectares planted in a kaleidoscope of hybrid and vinifera varieties from Baco 22A to Pinot Noir, some of them quite unsuited to making table wines of distinction in Central Otago.

Summer evening at Rippon, Lake Wanaka. Rippon

Their goat enterprise was successful but both Rolfe and Lois were more interested in their vines. To help them decide if they would commit to producing wine commercially, they spent 1981 living and working on a vineyard in France and took their children with them. They chose the village of Sigoulès about 7 kilometres from Montbazillac and 15 kilometres from Bergerac, east of the elite appellations of Bordeaux. The two oldest children were enrolled in the local school and became fluent in French, an experience that was later to benefit Nick professionally.

This sojourn convinced Rolfe and Lois to keep developing Rippon although it also alerted them to the depth of the commitment required to carve out a successful life in wine. Rolfe, by then 57, was later to declare in a discussion with journalist Ric Oram:

Time beat me. When I came back from France I realised that winemaking is not a hobby but a skilled profession. Difficulties there were, but not really in the growing of the grapes nor the ripening of them. The only problem was you cannot change overnight, throw your collar and tie away and become a viticulturist.

But time did not beat the Mills family. Rolfe and Lois continued to develop Rippon and its reputation. Their children extended it.

Table 8.6: Winemakers employed at Rippon Vineyard

Rolfe and Lois were slow to make wines in commercial quantities, but after their experience in France, they recognised the need to take technical advice. In 1985 they arranged to send 200 kilograms of grapes north to the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station to be made into wine and assessed professionally. They left their Müller Thurgau on the vines as long as possible to reach optimal ripeness but lost much of the crop to birds. Not to be thwarted, the following year they netted the vines and their first crop of Müller Thurgau was successfully fermented and bottled at Te Kauwhata where Rainer Eschenbruch endorsed the quality of the grapes and the resulting wine. This confirmation convinced them to employ Tony Bish from Hawke’s Bay as their first winemaker in 1986. They went on to employ a series of professional winemakers many of whom were also knowledgeable viticulturists (Table 8.6), building an enviable reputation for their wines in the process.

Nick Mills, who took over the viticulture and winemaking at Rippon from 2002 (his father died in 2000), attributes his own commitment to the vine and wine to Rudi Bauer. Between 1989 and 1992, when Nick was in his late teens and Rudi was working at Rippon, they spent time together – pruning, planting and talking. ‘Rudi sort of instilled in me the feeling that viticulture and winegrowing was something that I could potentially fall in love with,’ says Nick. ‘I got inspired at that time.’ But Nick had another talent to explore. He was a freestyle skier in the New Zealand team preparing for the Nagoya Winter Olympics when at the end of 1997 he hit a control gate in a high-speed turn and ‘lost my leg out behind me and blew it completely to bits. So that dream was out the window!’ His next four years were spent at the Beaune Polytechnic studying viticulture and oenology and working in the vineyards of Burgundy.

During the 1980s and 1990s, winegrowers in Burgundy became more and more concerned with reducing, or eliminating, many of the chemicals that had crept into their vineyard management. Centuries of growing vines on the same sites, and the increasing reliance on herbicides in the twentieth century, had resulted in the accumulation of undesirable chemicals in these vineyard soils. Tertiary institutions were embracing organic and biodynamic practices in the vineyard and cellar, teaching them and integrating Burgundy’s vine and wine history into their courses – notably the strong manual work ethic and respect for the vine held by the Cistercian order. Nick Mills was exposed to these ideas both in his studies and on the enterprises where he worked during his stages, or periods of practical experience. This experience deepened his commitment to organic and biodynamic practices and also to the people who were exploring and introducing them.

At enterprises like Domaine Jean-Jacques Confuron in the commune of Prémeaux-Prissey in the Côte d’Or, where organic and biodynamic practices were embraced, Nick Mills began accumulating a sophisticated knowledge of the biology of the vineyard and cellar. During his four years on the Côte from 1999 through 2002, Nick did stages at a number of diverse enterprises. With the 1999 Confuron experience under his belt, in 2000 he grasped the opportunity to work with Nicola Potel who is from a Volnay family but at the time was setting up a négociant business in Nuits-Saint-Georges. Here was a unique opportunity to experience the different nuances of the aromas, texture and flavours of Pinot Noir grown in the different communes of Burgundy by participating in their vinification. For the 2001 vintage, he arranged a job with Pascal Marchand at the Domaine de la Bougère, pruning and working in the cellar until the spring of 2002. Lastly, he worked in the prestigious Domaine de la Romanée Conti vineyard and cellar from April 2002 before heading home. Experience garnered at all these enterprises prepared Nick for his return to Rippon Vineyard.

He came back to a 15-hectare vineyard with 12 hectares of vines in production, about nine of them in Pinot Noir. By Burgundian standards the vineyard was a suitable size for a family holding. His experience in France had made him certain of one thing: ‘I was already convinced about biodynamics.’ His was a practical rather than an ideological attraction to the approach. Minimal intervention in the growing of the grapes and in converting them to quality wine is his philosophy and Central Otago is the ideal place to practise it. Its dry atmosphere reduces the incidence of many diseases that are a problem in other grape-growing regions of New Zealand. Consequently, Nick did not even consider using herbicides to control unwanted plants. He disced the whole vineyard and ‘created the mound underneath the vines so I could work the under-vine cultivator properly’.

From the beginning, Rippon Vineyard was organic. Achieving this certification required them to vinify grapes from their own vineyard only. When Rolfe and Lois began planting vines at Rippon no vineyards existed within tens of kilometres of them. They limited their applications of sprays until their practices were certainly organic, and verging on the biodynamic. As the operation became more commercial and Rolfe became less involved in the day-to-day and seasonal management of the vineyard Rippon drifted from its earlier ideals of limited intervention in the life of the vines. By the late 1990s, when nearby Wanaka growers pressed them to buy small quantities of Pinot Noir, they obliged and their organic status was compromised.

Nick Mills’ biodynamic beliefs in the benefits of manual labour and observation in growing grapes of quality have had consequences for everyone who is working at Rippon in the twenty-first century. Practices embedded in the Burgundian tradition are incorporated into daily organic and biodynamic routines. Parcels of mature Pinot Noir vines have been named after ancestors – Emma’s Block for the great-great-greatgrand-mother of the current generation of the Mills family and Tinker’s Field for the late Rolfe.

Twenty years earlier Nick had bought a hand hoe for Rolfe in Switzerland. They had fitted it with a kanuka handle. Hand cultivation of the vineyard had been part of their regime when Nick was growing up: ‘We were buying hand hoes from Mitre 10 and we went through dozens and dozens of them.’ But the rugged Swiss hoe had outlasted all others. So Nick used it as a template and had 20 more of them made up:

And we do an hour hand-hoeing every morning, across the board, everyone on the property. We arrive in the mornings, we shake everyone’s hands, we look each other in the eye and we go out and do an hour’s hard yakka every morning. It really galvanises a team. We’re in this together. That’s the shop people, that’s the winery people, that’s the office people, it’s everyone.

Rolfe Mills would undoubtedly have admired the depth of Nick’s tribute to this lineage and this place.

Quartz Reef

When Rudi Bauer arrived in New Zealand in 1985 he was probably the best-qualified vigneron in the country. He had already spent nine years studying the theory and practice of viticulture and winemaking, punctuated by regular examinations, and had worked in vineyards and cellars with international varieties such as Riesling, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Müller Thurgau as well as grapes native to Austria or Germany such as Zweigelt, St Laurent and Grüner Veltliner.

In March 1985 Rudi began working at Mission Vineyards in Hawke’s Bay where he stayed until June 1989. During those years he took three winter breaks – the first to cycle around the South Island, the two others to extend his international experience with vintages at Simi in the Sonoma Valley, California and at Sokol Blosser in Oregon. In the winter of 1989 he planted the second block of the Rippon Vineyard with Robin Dicey who was advising Rolfe and Lois Mills on their viticulture. Rudi had already established a reputation as a winemaker based on notable wines he was involved with at Mission, including their 1985 Gewürztraminer, 1987 Pinot Noir and 1989 Reserve Semillon. Winning Rippon’s first gold medal for Pinot Noir in 1990 enhanced his reputation as well as confirming his skills in the Central Otago environment.

Rudi left Rippon at the end of 1992 to work at the Giesen Wine Estate where he was one of their principal winemakers until November 1997. In accepting this position Rudi was not spurning Central Otago. By 1991 he had discovered the land he coveted on Bendigo Station and remained intent on exploring the possibility of establishing his own vineyards and cellar in Central: ‘I always wanted to come down here. That was a very clear call.’ His wife, professional photographer Suellen Boag, grew up in Dunedin and is equally as enthusiastic about Central Otago and especially Arrowtown where she spent holidays as a child.

Giesen’s brief for Rudi, undoubtedly influenced by his success at Rippon, was ‘to improve their red wine portfolio’. He was responsible for grapes from their Canterbury property, from land the Giesens owned in Marlborough, and for grapes bought from Marlborough growers. The experience included working with white grapes – notably botrytised Riesling, Müller Thurgau, Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Gris – but what confirmed the direction that Rudi wished to take was clear: ‘What for me was the best was dealing with Pinot Noir from two more regions.’ He added the distinctive Canterbury (Burnham) and Marlborough Pinots to his Otago experience.

In 1996, Rudi Bauer visited John and Heather Perriam to discuss the possibility of planting grapes on their Bendigo Station. ‘He asked whether we’d be interested in forming a partnership,’ recounts John Perriam. ‘He was looking at the Loop Road. I told him to bugger off because I was running around the world at that stage setting up Merino New Zealand.’ The Loop Road is a triangular side road with two entrances off State Highway 8 east of Lake Dunstan, about 30 kilometres north of Cromwell. At its eastern apex is the site of the former gold-mining settlement of Bendigo. Loop Road is on a flat terrace between 210 and 220 metres above sea level. On the southern arm of its triangle a relatively gentle concave slope rises above this terrace until at about 280 metres it becomes too difficult to cultivate with a tractor.

Rudi Bauer had long admired the slope as a site for a vineyard. He had observed it often from across the Clutha when driving between Wanaka and Cromwell: ‘And you look at it, and you say, “That’s not good enough, it’s west facing”, you know. And of course I made a mistake!’ They visited the site where Suellen used her watch in relation to the position of the sun to convince Rudi that the slope was within 10 degrees of due north. He became more enthusiastic, even harbouring thoughts of establishing a monopoly over a large chunk of these slopes.

Rudi and Suellen were keen to use the name ‘Bendigo’ for the nascent enterprise, but firms in the winegrowing area of Bendigo, Victoria in Australia had already captured that intellectual property. Within a 10-kilometre radius of Loop Road are numerous colourful names from Central Otago’s gold-mining era, especially of the creeks draining the hills south and east of Bendigo – Shepherds, Rise and Shine, Aurora, Chinamans, Pigeon, Raupo, Green Valley, Devils, John Bull, and even Firewood and Brewery. Rudi and Suellen chose the evocative name Quartz Reef even though Quartz Reef Creek and Quartz Reef Point are on the adjoining Northburn Station to the south of Bendigo Station.

Winter 2011 at Rudi Bauer’s Quartz Reef. Suellen Boag

Figure 8.3 Loop Road, Lake Dunstan, and the Bendigo Terraces

John Perriam was more interested in Rudi Bauer’s proposal than he initially let on, but had told him to ‘go away and if you can find us another partner in the old world that had a marketing infrastructure in place before we planted a grape then I’d think about it’. Three months later Rudi was back with the name of Clotilde Chauvet of Champagne. Her family owned a small, successful Champagne house in Épernay. Perriam’s response was to fly to France and spend time getting to understand the Chauvet enterprise as the family’s guest. That experience, together with his respect for Rudi’s knowledge and winemaking skills, convinced him to go ahead.

In 1996, Rudi Bauer, Clotilde Chauvet and John Perriam formed the Bendigo Estate Partnership. Bendigo Station had been the first high-country run to go through tenure review in 1986. This allowed owners to freehold some land while ceding vulnerable natural environments to the Department of Conservation, in some cases with closely controlled grazing rights. Perriam tried to convince the Department of Conservation to include the Bendigo slopes in the land reverting to the state because it was costly to keep the rabbits under control and was growing little tussock or other grasses: ‘I had tried to talk DOC into taking all the land right down to the road because it was full of rabbits. Now it’s some of the most valuable land!’ Until Rudi’s approach, Perriam had been unaware of the potential of the Bendigo slopes and higher terraces for growing grapes. But he did know the micro-environments of Bendigo station well.

Rudi had taken temperature readings on the proposed Bendigo land that confirmed its suitability for Pinot Noir. Its temperatures during veraison were very similar to the commune of Aloxe-Corton in the Côte de Beaune. Clotilde Chauvet’s experience at Rippon and skills in vinifying sparkling wine complemented his and were essential in producing the non-vintage Quartz Reef Méthode Traditionnelle. His plans for the future possibilities for the organisation of the enterprise were already clear:

Trevor Scott, one of our partners, bought another 15 hectares just beside ours. So the plan is that it runs with us, under one label, which makes a lot of sense. That’s a total of about 30 hectares. Let’s say on average that’s 250 tonnes, that’s 20,000 cases-plus. I do believe in time, most of the sparkling wine would be sourced from contract vineyards. I think that’s possibly a good call. Have the foundation and then we are not put under pressure. Basically we’ll do what Montana does now. We realise that we cannot rely fully on grape growers. We really have to do it ourselves. Maybe we could aim for 50 per cent.

Rudi recognises the advantage of having two strings to his Central Otago bow – Pinot Noir backed by a Méthode Traditionnelle. Clotilde Chauvet’s involvement at Quartz Reef for the first 12 years of its life removed some of the mystique surrounding Champagne, and Rudi is himself now skilled in its vinification. His quick calculation of the yield necessary to achieve 250 tonnes of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir works out at just over 8 tonnes of grapes per hectare. In the communes of the Champagne region proper, yields are often much higher than this, even for wines originating from elite houses.

Mondillo Vineyards

Domenic Mondillo, who trained in restaurant management and culinary arts in the United States, owned two restaurants in Queenstown and, in his words, ‘had the pleasure of employing Mike Wolter’, who worked as a kitchen hand for him in the late 1980s while looking after Ann Pinckney’s vineyard and winery:

I ended up going out to the vineyard with Mike during the day, because we were only open for dinner, and also started helping Mike in the winery at Taramea. It was a privilege to know him as an individual – and he was a huge inspiration to me.

Wolter went on to establish the Central Otago Wine Company with Sam Neill and his death in a winery accident in 1997 was tragic both for his family and for the close-knit community of Central Otago winegrowers.

Domenic was friendly with other influential members of the small Central Otago wine community of the mid-1980s including Rob Hay (Chard Farm) and Greg Hay (Peregrine) as well as Alan Brady of Gibbston Valley. By the time he sold the first of his restaurants in 1990 and the second in 1992 he had already begun a comprehensive private apprenticeship in viticulture and winemaking. Domenic had participated in vintages for more than a decade and pruned at Gibbston and other vineyards in most years.

By 1996, having completed the Eastern Institute of Technology’s viticulture and winemaking qualification, Domenic was running the viticulture for Gibbston Valley. His appointment there coincided with more Central Otago vineyards coming into production. The Bannockburn vineyards of Mt Difficulty and Felton Road, for example, were beginning to bear fruit in the mid-1990s but their wineries were not yet built. For the vintages of 1995, 1996 and 1997, Gibbston Valley bought substantial quantities of Pinot Noir fruit from them. Being one of the first functional wineries in Central Otago made it possible for Gibbston Valley to begin increasing its production with grapes bought from growers who were intending to make their own wine later. At the same time, it needed to start planting more of its own vineyards against the day when this contract fruit was no longer available.

The first vineyard developed was in Alexandra, just beside the racecourse on Dunstan Road, in 1999, and under Domenic’s stewardship Gibbston Valley also convinced John Perriam of Bendigo Station to sell them some land. It first purchased and planted two blocks on the gentle slopes west of the Quartz Reef vineyard. As the qualities of Bendigo’s north-facing, higher terraces were recognised, many other enterprises, including Gibbston Valley, continued acquiring land there. It has two parcels on the Chinamans Terrace, named after the creek draining the lower slopes of the Dunstan Range, as well as a large parcel east of School Creek on what has been christened Schoolhouse Terrace. By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, Gibbston Valley had accumulated a total of 75 hectares in six parcels as well as leasing several other vineyards, including two from John Perriam.

Mondillo’s four vineyards on terraces above the Loop Road, Bendigo. Alan Kwok Lun Cheung

Domenic and Ally Mondillo planted two of their own vineyard sites in the Bendigo locality. One is above the apex of the Loop Road with its highest point at 305 metres and the other further east on the Schoolhouse Terrace that is 388 metres at its highest point. They bought these sites from Bendigo Station for $15,000 per hectare when land suitable for viticulture in Marlborough was selling at over ten times this price. Their four interconnected vineyards above the Loop Road are on three levels all facing slightly west of north with steeper land separating them but linked by carefully sculpted tracks. They are all exposed to the afternoon sun. Pommard vines (clone 5) make up 40 per cent of the total and the more recently selected Dijon clones (114, 115, 667 and 777) make up the remaining 60 per cent of the vineyard’s Pinot Noir clones. At this stage of the evolution of their enterprise the Mondillos are making only two wines – Pinot Noir and Riesling. Their winery equipment consists of just three 6-tonne stainless-steel fermenters and Rudi Bauer vinifies the grapes for them in Cromwell. They vinify only about 25 or 30 per cent of the grapes they grow and Pernod Ricard buys the rest.

Right from the first vintage in 2004 the Mondillo Central Otago Pinot Noir impressed judges in blind tastings and won a haul of medals. With the vines now older, and Domenic and Rudi understanding the Bendigo environment more deeply, recent vintages have eclipsed earlier results. The Mondillo 2008 Pinot Noir was awarded a gold medal and judged champion wine at the 2010 Royal Easter Show. By 2009 their Pinot Noir came from vines being grown sustainably and received a ‘Pure Gold’ in the Air New Zealand Wine Awards of 2010. These local results have been endorsed by commercial success in the United States.

The vineyards along the Loop Road are an excellent example of the need to be wary of spring frosts in Central Otago. In the spring of 2003, for example, frost significantly reduced the crop on some of the vineyards on the Bendigo flats. Aurora’s crop was severely affected. Even the lowest rows of Quartz Reef’s Loop Road vineyard had some frost damage because the cool air ponded near its poplar shelterbelt and flowed back to the vineyard. Gibbston Valley responded by installing fans for frost protection on its two more gently sloping vineyards west of Quartz Reef. Frost-protecting fans are also installed on two of the Mondillos’, almost flat, Loop Road vineyards.

To avoid ‘green’ flavours in his wine, Domenic Mondillo does his best to keep his yields down, but not too low, somewhere over 5 tonnes but less than 8 tonnes per hectare. He believes that if yields are any lower there’s a danger of prematurely getting high sugars in Pinot Noir before getting ripeness. The objective should be to maximise the flavour development without the sugars being ‘ridiculously high’, as too many shrivelled berries give a port-like character to Pinot Noir that is ‘equally undesirable as green flavours’. Like other viticulturists in Central Otago, during the late spring and summer he measures and keeps a close eye on the evapotranspiration numbers each week. In many vineyard regions of New Zealand viticulturists expect the canes to reach about the top of the post at flowering. Domenic’s experience of numerous sites in Central Otago suggests that the canes seldom reach this level by flowering. He sees his overriding role in the vineyard as achieving a balance between helping the vines to grow while limiting their vigour. This involves being careful with applications of water, in particular, and also fertiliser.