A DRAFT SCIENTIFIC REPORT WAS SHUTTLED AROUND THE PENTAGON, WHITE House, IGY Committee, and AEC, undergoing revisions and refinements to ensure that no more secrets were revealed than was already the case. The AEC was concerned only with disclosing the yield of the Argus shots, so that material was duly removed. After some further tweaks here and there, White House Press Secretary James Hagerty released the report on March 25, with Herbert York providing the scientific perspective.

For the administration, it was an exercise dedicated to emphasizing the position that Argus had essentially been a massive IGY science experiment with perhaps some military aspects, rather than a military project that happened to involve some science that could be conveniently shielded by the IGY. A memo from Assistant Secretary of Defense Murray Snyder to General Goodpaster offered some helpful suggestions for talking points to accompany the scientific release, complete with possible questions and answers.

For one, on the issue of delaying the release of the story, the memo noted that “despite rumors to the contrary” (apparently an oblique reference to Senator Anderson), the JCAE had been fully informed of the military implications of Argus and had opposed publication for that reason just as much as the Pentagon. Snyder mentioned the Washington Star editorial that had gone on about the “reasonable and necessary” need for “holding one’s tongue on occasion” and suggested that reading a few lines from the piece might come in handy. In response to the question “was the publication of this story a breach of security?”, Snyder suggested a response of “it should be obvious that the original disclosure of the plans for the Argus project, weeks before it occurred, was a serious security violation and a reprehensible thing,” adding that efforts were underway to identify the source of the original leak to Baldwin.1

The report released by the White House glossed over any military questions to focus solely on science, describing the theories of Christofilos, the observed Argus effects, and how the various IGY resources were used to observe and record them. “The scientific aspects of these experiments … are regarded by many participants as one of the major achievements of the International Geophysical Year,” said the report. Still, “it was clear that the undertaking involved a mixture of scientific and military interest.”2 The New York Times reported that “Despite the intensity of the artificial radiation, Dr. York dismissed the possibility of creating radiation belts with atomic explosions to kill the passengers in any future space vehicles.”3

Not everyone in the scientific community agreed with that assessment, however. Victor Weisskopf of MIT, physicist and Manhattan Project veteran, suggested at a meeting of the American Physical Society that Argus had demonstrated that the radiation environment of outer space was threatening enough that future space travelers might have to restrict themselves to the polar regions, where “escape hatches” allowed a sort of “end run” past the radiation into outer space. As reported by the Montreal Gazette, “The Project Argus high-altitude nuclear explosions strengthen a view that the first launching stations for spaceships probably will have to be placed in Polar regions.” Also, Weisskopf “did take issue with some of the published reports about things we might be able to do as a result of the Argus test,” specifically the notion that, as some sources had reported, “neutrons from nuclear bombs exploded at high altitudes could be used to ‘trigger’ an A-bomb warhead in an enemy missile prematurely.”4

While some scientists questioned a number of the official and unofficial contentions swirling around the whole Argus story, others dismissed the entire enterprise as “a total failure.” Joseph H. Irani, radiation laboratory director at defense contractor Aerojet General, felt so strongly about the matter that he called the Los Angeles Times. The paper requested that he send them a letter explaining himself, which he proceeded to do in great detail.

“Today, when the free world is faced with a ruthless enemy who has no gods nor conscience, the United States is toying hopelessly with a wasteful and trivial experiment,” Irani claimed. “Such an undertaking aimed to build up our defenses against incoming missiles can result only in draining our economy, creating false confidence, increasing fallout and eventually losing both cold and hot wars. So far the results from Project Argus show nothing that we did not know before or can not prove on paper or in the laboratory.” Specifically, Irani took issue with the idea that radiation from an Argus-type shield could ever be strong enough to knock out warheads, or to effectively blackout radio and radar. Despite being hailed “as tremendous by some and as spectacular by others,” Irani argued that to the general non-scientific public, “it is whatever the official and scientist calls it. It may be called a success while in truth it is a failure. On the other hand, the Russians may be concentrating on more tangible and less screwball ideas than we are.” Irani also raised the specter of nuclear fallout from high-altitude tests, tying in his objections to the ongoing test-ban campaign. Although he made clear that he was speaking only for himself and not for Aerojet, Irani proclaimed Argus “a desperate attempt on the part of our so-called eminent scientists to find a solution for anti-missile missiles.”5

Some in the scientific community assailed Pentagon secrecy as the cause for overblown and misleading expectations about Argus. “It is not … the delay in publication of the scientific reports which most needs attention. It is instead the mistaken conclusions in news reports that a magic film of radiation may shield us from missile attack,” wrote physicist William Selove, vice chairman of the Federation of American Scientists, to the New York Times and several other major newspapers. That assertion, said Selove, “is a delusion … More candor in the statements from official quarters would lead to much less self-deception by the public.” And such self-deception could only lead to disaster: “Unless the people and the governments make a real effort to understand the overwhelming effects of nuclear war and the fact that a real defense against intensive intercontinental ballistic missiles H-bomb attack does not exist and quite possibly never will, we shall probably stumble into devastation.”6

Aside from such voices of dissent, however, the White House release seemed to do its job to almost everyone’s satisfaction. “According to the White House, Argus had always been considered part of the IGY, and the test had not been previously announced so that scientists could follow normal procedures and sort out the militarily relevant information from the scientific,” wrote Mundey. “What had been born a military test had been rechristened an anti-militaristic civilian scientific experiment.”7

Still, the largely successful attempt to recast Argus in the innocuous and noble light of scientific inquiry didn’t explain why the Pentagon remained so exercised about its release to the public. Testifying before Congress several weeks later, Snyder was asked whether he considered the Argus story a breach of security. “In my opinion it was a breach of security to print this story unless it was declassified,” he responded, explaining that once the Department of Defense had been informed that the story was about to be published by a certain newspaper, it hurriedly declassified the scientific aspects to limit the damage. “The name of the newspaper was not mentioned,” the New York Times noted archly.8

President Eisenhower also commented in a statement that “we regret that unknown persons gave out information prematurely and selectively to a single newspaper about the Argus experiments. This unauthorized step removed the decision on release from the orderly processes of Government. It is clear that whoever made this information prematurely available did so without any authorization on the part of the Government. In my judgment it is not in the overall interest of the United States for individuals to decide, on their own, whether and when restricted material should be made available to the press.”9

Another reason for the administration’s reluctance to reveal the existence of Argus was the reaction of foreign governments—not merely the obvious and understandable desire to keep the Soviet Union ignorant of the entire affair, but the political difficulties of carrying out such an enterprise without the consent of—or even consultation with—allies and other affected nations. For example, Brazil, in whose general neighborhood the United States had proceeded to detonate nuclear weapons without any sort of notice. Their reaction was less than enthusiastic. The Brazilian press railed about “atomic dust poisoning men in South Brazil” and that “the radioactive cloud produced by three bombs already may be producing effects on men, animals and vegetables.” Brazilian scientists warned of “birth monsters,” though others reassured their citizens that no excess radioactivity had been detected.10

Nicholas C. Christofilos, Greek-American physicist, photographed in 1971.

(Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory)

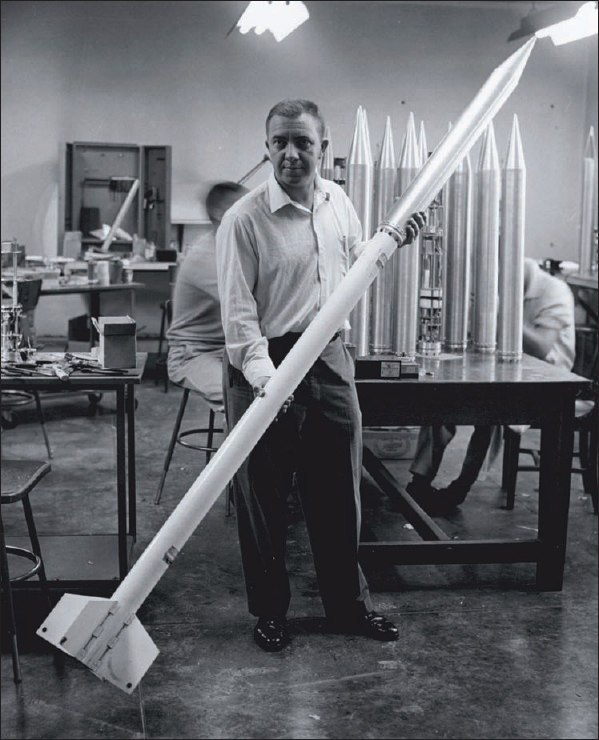

Physicist James Van Allen, here pictured posing in his Iowa laboratory with one of his rockoons.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

A full-scale model of Explorer 1, America’s first satellite, held by its creators. The team was gathered at a press conference at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, in the early hours of February 1, 1958, to confirm that the satellite, which had launched a few hours before, was in orbit. From left to right: Jet Propulsion Laboratory director William Hayward Pickering, James Van Allen, and Wernher von Braun.

(Credit: NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory–Caltech)

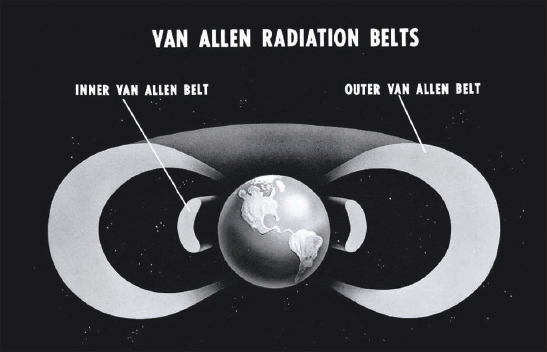

The data from Explorer 1 and Explorer 3 resulted in the discovery that the Earth was encircled with bands of radiation, trapped by the planet’s natural magnetic fields; these became known as the “Van Allen radiation belts.”

(Credit: NASA)

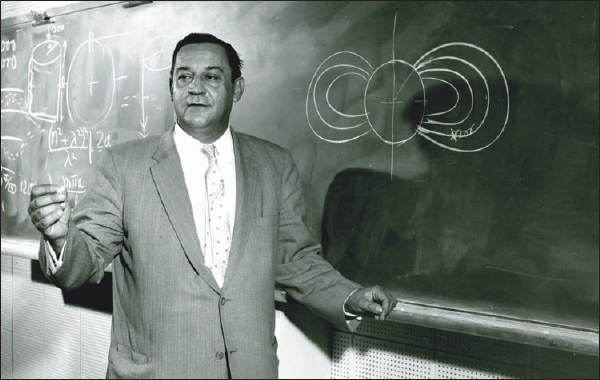

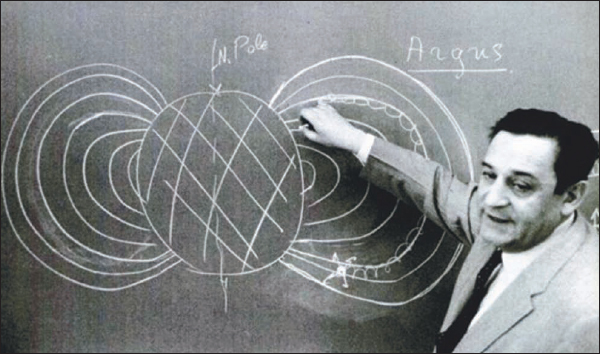

Christofilos explains his latest “crazy idea,” which he coined the Argus effect.

(Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory)

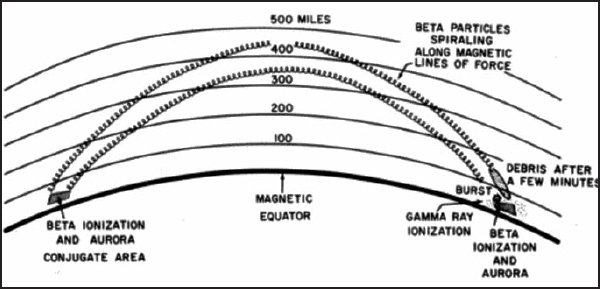

A diagram of the Argus effect.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

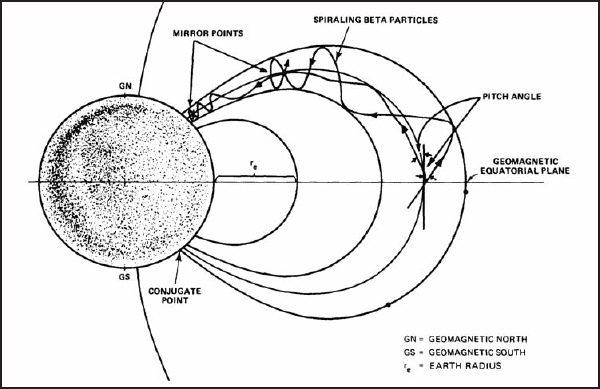

Another diagram of the Argus effect, illustrating how the high-energy electrons produced by an outer space nuclear detonation travel back and forth along the Earth’s magnetic lines of force.

(Credit: United States Department of Defense)

Christofilos explains how a magnetic field encompasses the Earth. He theorized that, if a nuclear bomb was detonated along the planet’s magnetic field, some of its radiation would be trapped and would travel along lines of magnetic force to a point at the opposite end of the line (known as the magnetic conjugate area), spreading around the Earth in a thin shell of electrons. Christofilos suggested the possibility that the Argus effect could be used defensively.

(Credit: Life Magazine, 1959, reprinted in Annals of Iowa, Volume 70, 4, Fall 2011)

Rear Admiral Lloyd M. Mustin, reluctant commander of Task Force 88, which was formed by the Pentagon’s Armed Forces Special Weapons Project to carry out the highly clandestine Operation Argus.

(Credit: Mike Green, NavSource Naval History)

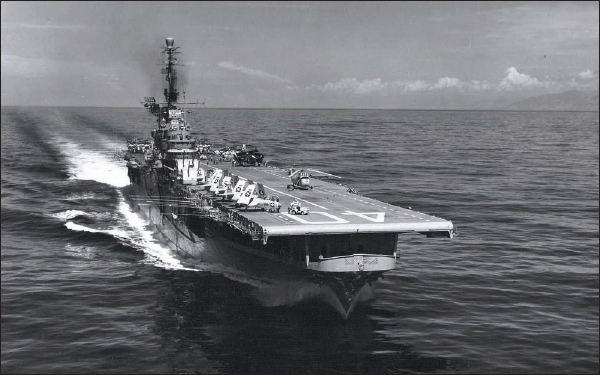

The USS Tarawa, the aircraft carrier that served as Task Force 88’s command ship and Mustin’s headquarters during Argus.

(Credit: Mike Green, NavSource Naval History)

The USS Norton Sound (AVM-1), the ship that would launch the first nuclear weapons into space. The Sound had a vast aft deck that made her a perfect missile-launching platform.

(Credit: United States Navy)

Two of the Grumman S2F Tracker aircraft of Tarawa’s VS-32 “Norsemen” squadron that patrolled the Argus operations area for unwanted intruders and also conducted observation flights during the tests.

(Credit: Allyn Howard, NavSource Naval History)

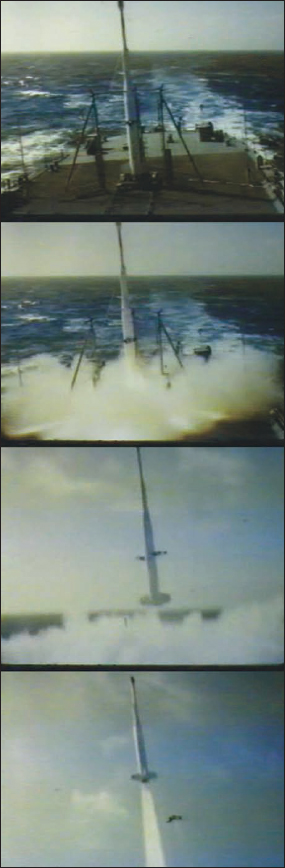

A sequence of frames from an X-17a test-firing film on the Norton Sound. Note the spin retrorocket package falling away in the final frame.

(Credit: Department of Defense)

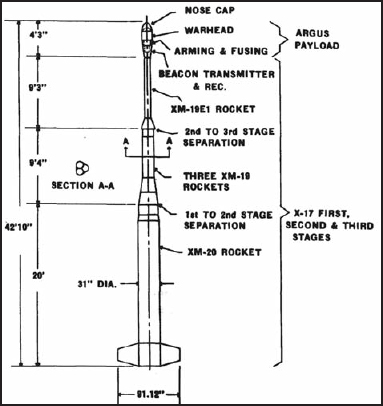

Diagram of the Lockheed X-17a rocket that would loft the Argus warheads into space from the deck of the Norton Sound.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

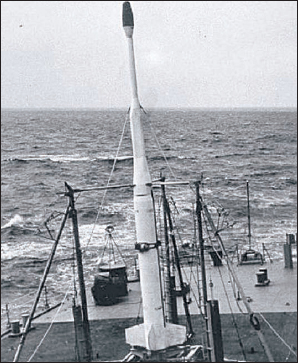

X-17a missile ready for test firing from the Norton Sound.

(Credit: United States Navy)

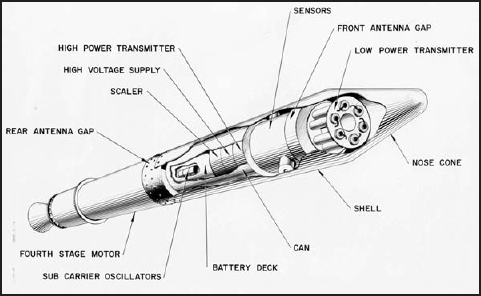

Explorer 4, Van Allen’s satellite that would monitor the effects of Operation Argus in space.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

Before shipping it off to Cape Canaveral, Van Allen plants a farewell kiss on the Explorer 4 instrument package as Carl McIlwain (center) and George Ludwig look on.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

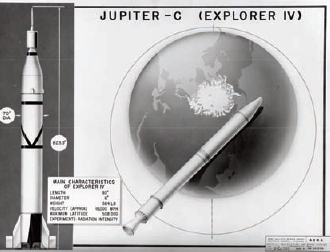

The Jupiter-C launch vehicle that would hurl Explorer 4 into orbit.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

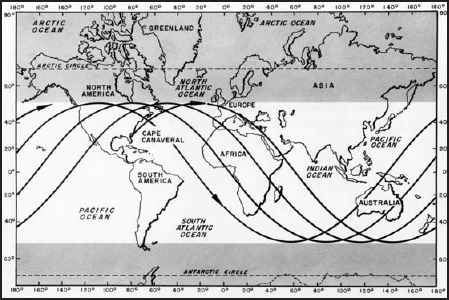

The plot of Explorer 4’s first four orbits.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

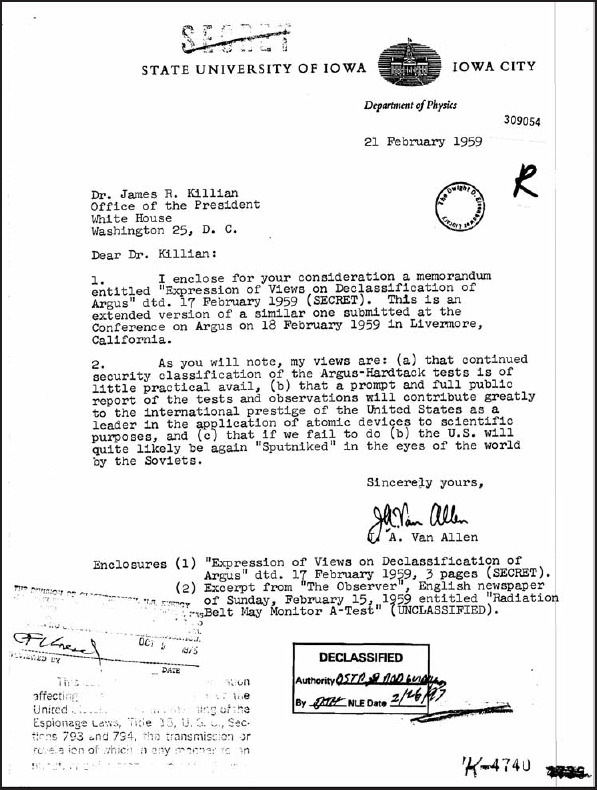

The cover letter of a missive from James Van Allen to James Killian urging for the declassification of Operation Argus.

(Credit: University of Iowa Libraries)

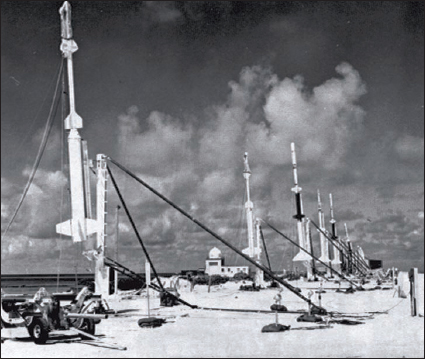

After Operation Argus proved a success, the US once again decided to detonate nuclear weapons in space to test the limits of the now-confirmed Argus effect. Called Operation Fishbowl, the test series was launched from Johnston Island in the Pacific, with various shots at different altitudes and nuclear yields. An array of sounding rockets carrying instrumentation for scientific measurements undergoes liftoff preparations before the Operation Fishbowl high-altitude nuclear tests.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

Operation Fishbowl’s Bluegill Prime launch pad explosion would require major cleanup, including decontamination of the irradiated launch site. Workers in radiation suits inspect the remains of the Thor missile engine after Bluegill Prime.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

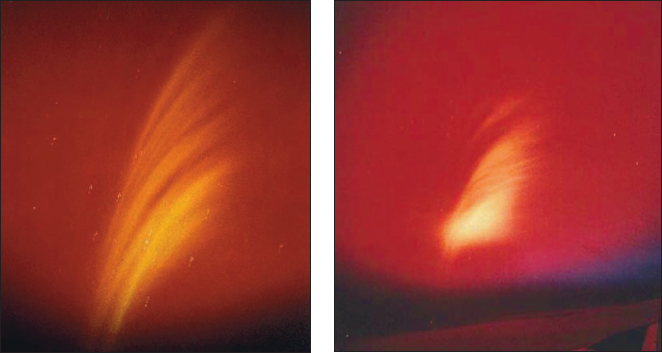

Photos of the effects of the Starfish Prime shot, which produced a light show and boreal effect in the nighttime sky.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

The detonation of Starfish Prime seen through a cloud layer in Honolulu.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

The Starfish Prime fireball from Hawaii.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

An upper atmospheric photograph of the Starfish Prime explosion.

(Credit: Defense Nuclear Agency)

On the morning of March 19, 1959, one of the greatest secrets of the Cold War became one of its biggest stories when Walter Sullivan and Hanson Baldwin ran their story on Operation Argus in the New York Times.

(Credit: New York Times archive)

On October 7, 1963, President John F. Kennedy signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, officially ending the era of nuclear testing in the atmosphere and outer space.

(Credit: JFK Library)

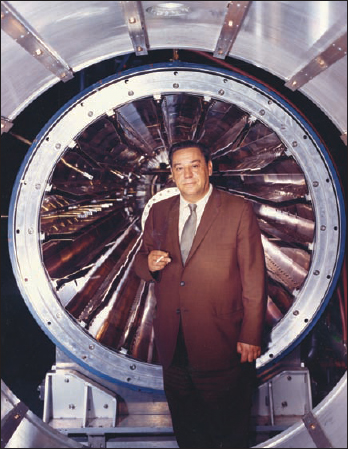

The Astron fusion experiment at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the center of Nicholas Christofilos’s work after Argus. The photo shows Christofilos’s linear electron accelerator.

(Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory)

Christofilos in 1968. He died in 1972, never realizing his grand dreams for Astron.

(Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory)

As the National Academy of Sciences Argus symposium approached at the end of April, efforts continued to figure out what else needed to declassified, both to comply with IGY agreements and to portray Argus as chiefly a scientific experiment. The Pentagon, naturally, continued to play things quite close to the vest, while the scientists, led by Van Allen, pushed for the release of more data, such as shot yields, exact times, and precise latitudes and longitudes.

In a letter to Killian shortly before the symposium, US IGY satellite committee chairman Richard Porter and IGY US executive director Hugh Odishaw set out the scientists’ case. “Such data are necessary if the various papers having to do with observed effects are to be scientifically meaningful,” wrote Porter and Odishaw. They pointed out that because “a competent scientist” could already figure things out fairly accurately from the already-released data, there was no useful purpose to be served by keeping it classified. And exact data would be far more valuable. “It will not suffice to permit a few US scientists to use these data and then, without disclosing their calculations, state that a particular theory has been verified or not verified.” Scientists, Odishaw and Porter were saying, needed to show their work. They argued that such information could easily be disclosed while still keeping secret military details such as the types of warheads and rockets used.

Again, there was also the issue of international prestige and politics. “It is important to give the greatest possible appearance of frankness in order to offset the impression that the United States has not lived up to its responsibilities in an international program,” the scientists warned. “Even though the Argus experiment, as such, was not officially a part of the IGY”—as the White House was claiming, went the implication—“their relationship appears now to be inextricable. Both the domestic and foreign press have accused the United States of cynicism in conducting a secret military experiment within the framework of the International Geophysical Year program … if data basic to scientific understanding are withheld, the world will question US conduct in this matter.” Greater openness would also “aid in deflecting alarmist interpretations of the experiment, particularly with reference to fallout.”11 After further discussion with York, Killian recommended the release of more—but still incomplete—details.

On April 29, Christofilos, Van Allen, and the rest of the Argus scientists finally presented their (mostly) complete results to the world in a packed house in the Great Hall of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington. With the imposing (at least to the lay public) title of “Scientific Effects of Artificially Induced Radiations at High Altitudes,” the NAS symposium was intended to cover the full range of Argus scientific results, with all the major players participating and presenting papers on everything from the Explorer 4 satellite observations to the Jason sounding rocket measurements and other ground observations.

In his introductory remarks, symposium chairman Richard Porter also added to the general confusion. “Despite some newspaper stories to the contrary, there was no commitment under the IGY to exchange information with other nations on the Argus experiment,” he stated. “Argus was not an IGY program; it was a Department of Defense effort.” But because “the Department of Defense and the Atomic Energy Commission have now released the information you are about to hear this morning so that it can be made part of the synoptic geophysical record,” he proceeded to disclose reasonably approximate times and locations of the Argus shots.12 The scientists had won this particular argument, at least to some degree.

Then the presentations began. First up was Nicholas Christofilos himself. He sketched out the background of Argus, including how he had originally conceived of the whole idea and how it had grown out of his Astron fusion reactor research. The Astron reactor, he explained, involved the idea of creating a cylindrical layer or “bottle” of electrons to contain a high-temperature magnetic plasma. Because he became interested in space after the first Sputnik was launched, “it occurred to me to extrapolate this idea of the electron layer to global dimensions.”

No doubt to the relief of both Pentagon officials and scientists in attendance, Christofilos neglected to mention the possible military implications of such an idea, noting instead that “it is obvious that the scientific aspect of such experiments is extremely important.” He recounted the discussions at Livermore, his first classified paper, and the Argus proposal it eventually inspired, confirming that it was Van Allen’s discovery of the Earth’s natural radiation belt that tipped the balance and convinced everyone that Argus had to be done.

After completing a general summary of the project and the observed scientific results, Christofilos argued that they were just beginning: “Continuation of the Argus experiments … may yield new information in addition to that anticipated … there is now available a new tool for exploring the part of outer space encompassed by the geomagnetic field, and for clarifying the phenomena of interaction of the earth’s magnetic field with various charged particles of natural or artificial origin.”13

As befitted his lone-wolf reputation, Christofilos presented his paper solo, but the remainder of the presentations were team efforts. Next up was Van Allen, with Carl McIlwain and George Ludwig also credited as authors on the paper titled “Satellite Observations of Electrons Artificially Injected Into the Geomagnetic Field.” Van Allen explained again how “the discovery of the existence of the natural, trapped radiation served as an over-all validation of the Argus proposal.” He proceeded to spell out the Explorer 4 data in great detail, with a great array of charts, graphs, maps, and other visual aids. And he emphasized that the satellite data proved both that the Argus effect was a reality, and that the radiation belt he had discovered the previous year was indeed a natural phenomenon and not somehow created by secret Soviet atomic blasts. He also noted that despite previous estimates, the Argus radiation shell had persisted at least until the previous December. The Pioneer 3 space probe, launched on December 6, 1958, in an unsuccessful attempt to reach the Moon, nevertheless reached an altitude of slightly over 63,000 miles, and before falling back to Earth managed to pick up some faint vestiges of the Argus radiation shell, weak but still active even after three months. Those traces had disappeared by the time the next Pioneer was launched in early March 1959.14

Explorer 4 may have been the most visible part of the Argus project before the whole thing became public, but the Jason sounding rocket observations also attracted a lot of interest once they were revealed. The Air Force scientists in charge of that effort—Lew Allen, William Welch, and several other colleagues—detailed their part of the story. The data collected by the Jason rockets “agree qualitatively with those measured by the satellite Explorer IV,” they reported, noting that the rockets also collected some additional information not possible with satellite observations.15 That was followed by two other members of the Jason team, Jasper Welch and William Whitaker, who offered a heavily mathematical presentation on the theory of trapped electrons. Finally, Philip Newman of the Air Force Cambridge Research Center and Allen Peterson from Stanford gave separate presentations on the various Argus data collected from the ground, including radio, radar, and visual observations.

Over the next several days, the scientists dominated the world news. Newspapers presented their findings with elaborate diagrams and graphics. Perhaps as a bit of Cold War propaganda boasting of an American triumph, even the United States Information Agency got involved, featuring Argus on their “New Horizons in Science” English language radio program broadcast on the Voice of America on May 7. The show featured recorded excerpts from Porter and Peterson at the NAS symposium, and though it didn’t do the same for Christofilos (possibly because of his heavy Greek accent), it reported his declaration that Argus provided “more accurate knowledge of the true shape of the Earth’s magnetic field, knowledge that may be of practical importance in radio communications and weather predictions.”16

Christofilos, however, did speak about Argus on a different Voice of America program broadcast in the Greek language. His proud parents, still in Athens, listened in on one of the still-operating radios their son had built himself during his youthful electronics tinkering days.

The scientific details of Argus were fascinating enough for geophysicists and space scientists, but they also pointed to definite military and political considerations for anyone who cared to approach them from that perspective. Although it had perhaps not been the intention of Van Allen and his colleagues, the wealth of data they had now released also demonstrated quite conclusively not only the possibility of detecting high-altitude nuclear explosions, but more importantly, precisely how to do it—and the vast amounts of data that could be gleaned from such observations. Naturally, anything that American scientists could do, Soviet scientists could do as well, a fact not lost on the Pentagon and White House. These, of course, were much the same arguments that Van Allen and others had used to fight for the declassification and release of Argus data.

At the symposium, the scientists had alluded rather obliquely to such concerns, including the mention of how high-altitude nuclear detonations could interfere with radar and radio communications and Christofilos’s observation that, as the internal newsletter of his employer Livermore Lab later reported, “Such experiments must be restricted to small bombs in the kiloton range, because megaton fission released in the proper location in outer space could create a radiation hazard for several days or more for outer-space travelers.”17 Some in the press seized upon this to play up the radiation shield angle. “Expert Says One Bomb Can End Satellite Life Around World,” declared a Washington Post headline. The accompanying story opened with the alarming lines: “A 1-megaton atomic bomb exploded at the proper point in outer space can girdle the earth with a band of lethal radiation within minutes. A man on a satellite within that band would be dead in less than 3 hours.”18

But whether such a phenomenon was ultimately a hazard or a weapon depended upon your point of view—and on the identity of the affected space travelers, spacecraft, or missiles. The Christofilos Effect (or alternatively, the Argus Effect) had been conclusively, if only weakly, demonstrated by the low-yield Argus tests. What would happen with more powerful nuclear explosions? Could the Argus Effect be used as Christofilos had originally intended, to destroy enemy missiles, and if not, to at least cripple them? And if that wasn’t possible, what about using it to disrupt and knock out enemy communications and radar systems?

Such questions were on the minds of congressmen at a closed hearing before the House of Representatives Committee on Science and Astronautics a couple of weeks before the NAS symposium. York and Shelton, as the top Pentagon scientists for Argus, both testified. Committee chairman Overton Brooks and his colleagues managed to learn some intriguing things about Argus that had not been revealed in the news articles, the White House release, and the NAS symposium.

York laid out the general chronology and details, including the reasons for keeping certain information classified. Some of the confusion in the press had actually been working to the government’s advantage. “The newspapers published the altitudes as 300 miles. We have simply let it stand there. All we have said is that the shot burst was well outside the earth’s atmosphere. The reason for keeping this classified is that one of the ideas and—practically everything that was seen in this experiment confirms the ideas of Christofilos.”19

As for the locations and times of Argus, “The reason for keeping the precise time secret is that when you explode a bomb anywhere around the earth, there are certain radio signals which are produced,” explained York. “The observation of these radio signals are important in connection with detecting explosions.” So specifying the shot times within about ten minutes before or after “is good enough to be useful in connection with the scientific applications of this data, but it is vague enough so that we think that the Russians can’t work this down to the point where they know what kind of signals this produced.” York also pointed out that because the Argus shots were relatively small, press reports of worldwide effects “are based on a confusion of these shots with the high-altitude shots in the Pacific which did produce large-scale disturbance”—a reference to the Teak and Orange shots that had preceded Argus in 1958.20

Because the hearing was conducted in secret, the questions focused more on the military ramifications of Argus than its scientific discoveries. The congressmen seemed particularly intrigued by the effect of high-altitude nukes on communications, especially when York observed: “If instead of being small, if this bomb had been very large, then shooting it in the South Atlantic would probably have interfered with communications across the North Atlantic. So that it gives you the odd opportunity of firing a bomb in a completely remote part of the world which is under your control—or under no one’s control, perhaps—and producing a communications interference at a place which is not available to you. In other words, if we fired this bomb in the Indian Ocean we could have disrupted shortwave communications in the vicinity of Moscow.” Although that “would take a bomb of large yield and not this little bomb,” it was “a rather interesting possible weapons effect … if you do it in the South Pacific, somewhere around the tip of South America, you can interfere with communications in Washington.”21

Pennsylvania’s James Fulton, after some queries on Argus science, returned to the military implications, asking York if such an effect might be used “to get through radio, radar, and other communications that Russia or any Iron Curtain country might have set up as a defense … to have our strategic air force pass into Russia without detection?”

“That is one of the things people had in mind here,” York responded. He emphasized that there was still much that remained unknown, making it difficult to seriously discuss specific strategic or tactical military possibilities. Was there even a consensus that there was any point in striving for some kind of missile defense system? “I think there is simply a divergency of opinion here,” said York. “There are people who feel it is worth continuing. There are a few who feel it is worth speeding up. There are a few who feel that there just is not anything along this line at all … that is why we have to keep at it all the time.”

Another congressman wanted to know about fallout from these high-altitude explosions. “We are still working on that question,” said York. “We do not know the answer.” He noted, however, that because fallout from high-altitude explosions takes much longer to return to earth, most of it is probably decayed by the time it reaches the ground.

The politicians were highly exercised by the secrecy issue, especially how a supposedly classified project was uncovered by a newspaper. How was such a serious security breach possible? Was everything being done to locate the source? Shelton assured the Committee that it was. That didn’t placate Frank Osmers of New Jersey, who worried that if the New York Times could find out about Argus, then “I presume the Soviet Union knows as much about it.” Congressman Emilio Daddario of Connecticut, not accepting York’s assertion that Hanson Baldwin and Walter Sullivan had just been supremely persistent and dedicated newsmen, even raised the specter of a possible spy ring: “Apparently there is a chain which got the plans into the hands of these people … and any program of whatever importance we put through from this point on, we have to assume it is not only in the hands of the newspaper but in the hands of the enemy as well. If someone has so little regard for the security of the country, then they certainly would not have any less regard for the security of giving it to the agents of a foreign country.”

“In this case the Soviet Union did not seem to have it,” York replied patiently. “If they had it, it would have been to their advantage to release it.” As Shelton had previously testified, had the story broken publicly before the Argus operation, “we probably would not have conducted the experiment.”

“We have paid for a fine piece of research for Russia to use against us,” complained Leonard Wolf of Iowa, worrying about what would happen if the Russians decided to disrupt communications in Washington by detonating a bomb at Tierra del Fuego.

“If you want to interfere with communications in Washington, the best thing to do is put the bomb right here,” York said dryly. He agreed that “you can do it by putting it in Tierra del Fuego,” but observed that “it is of much greater concern if they put it right here, because then they can interfere with communications by killing us all.”

The hearing ended on an appropriately apocalyptic note, as Utah representative David King noted that many of his constituents “seem to be very concerned about these experiments that go off in the areas that carry such lethal potentiality with regard to the human race. They seem to feel we are tampering with great forces, the implications of which we know not. We are going willy-nilly not knowing where it will take us. If we make a mistake we will sterilize half the race. They take a dim view of the whole thing.”

“I know that people do,” York replied. But he reassured the Committee that these high-altitude experiments “just don’t do that … I don’t know how to prove that to somebody who doesn’t want to believe it.” He added that “I suppose it is possible we could stumble on to something. We do consider this as carefully as we can … I guess anything is possible. We are as sure as we can be that it is not possible, that it isn’t dangerous.”22

However, it was becoming increasingly obvious that, spurred by the revelations of Argus, the Teak and Orange tests of the previous summer, and the rapidly growing campaign against fallout and nuclear testing that had led to the test moratorium, a great many people both in the US and around the world weren’t quite so confident with official reassurances. In fact, just as others pondered the possibilities for further Argus-type experiments after the test moratorium lifted, the public was worrying more and more about what might happen if atomic and thermonuclear weapons continued to be detonated with such careless abandon all over the world—and how it could be stopped once and for all.