Lisbon’s cathedral was built shortly after Afonso Henriques had taken Lisbon from the Moors in 1147, and stands on a site once occupied by the city’s main mosque. Today’s crenellated Romanesque building is a much-restored reconstruction, rebuilt in various architectural styles following earthquake damage. It is also an archaeological site, with new finds made regularly beneath the cloister – originally excavated to reinforce the building’s foundations.

NEED TO KNOW

Largo de Sé • 218 866 752

Largo de Sé • 218 866 752 Church • 9am–7pm daily

Church • 9am–7pm daily Cloister and Treasury • 10am–6:30pm Mon–Sat • Adm: €2.50; concessions €1.25

Cloister and Treasury • 10am–6:30pm Mon–Sat • Adm: €2.50; concessions €1.25- The Sé is a very dark church, and much of interest in the chapels is literally obscured. Head for the lighter cloister, and try to go in the afternoon, when the low light enters the façade’s rose window.

- A great place for a relaxed drink in the neighbourhood is the charming Pois, Café, where the Austrian owners are helping to keep Alfama cosmopolitan.

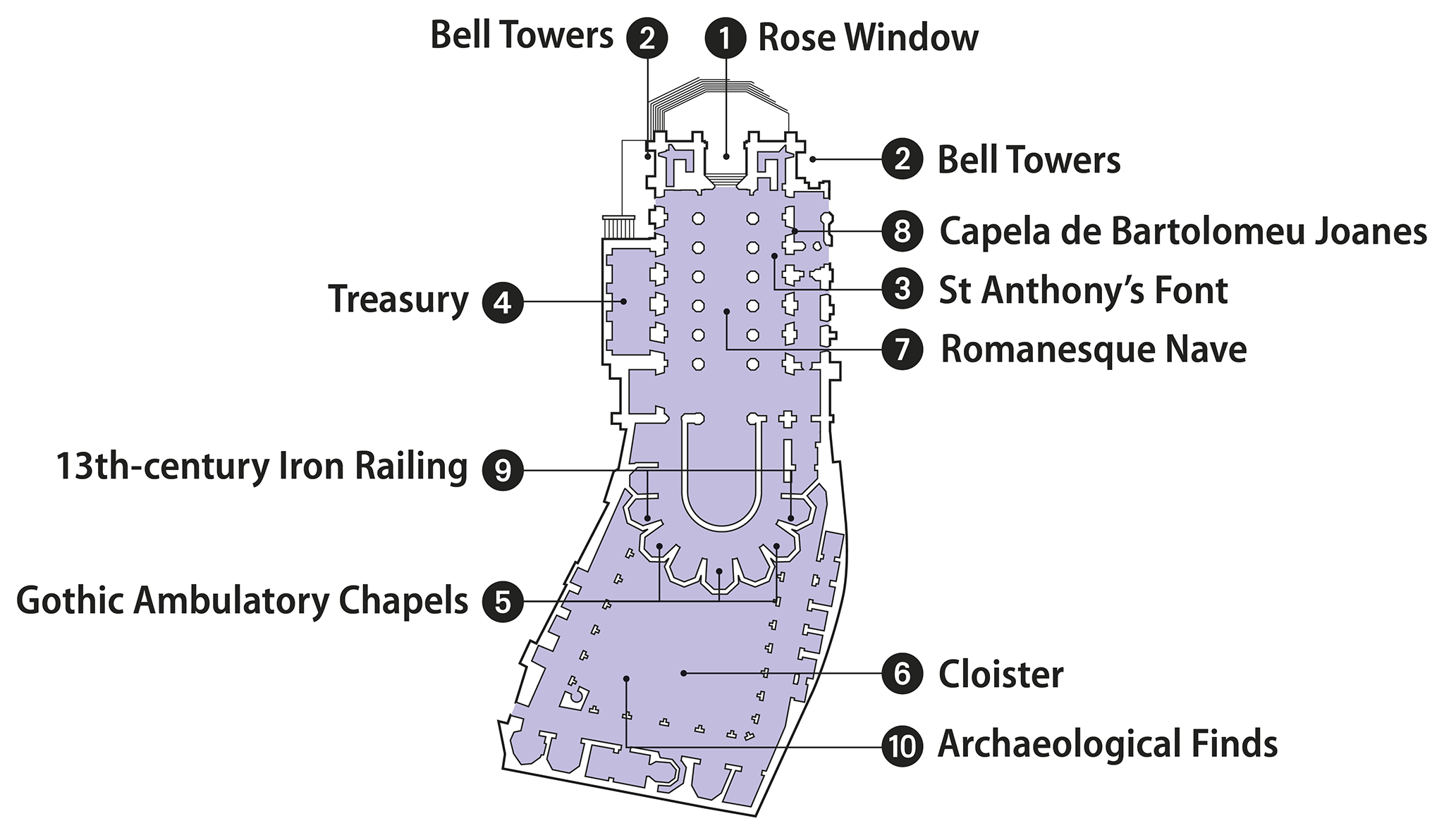

1.Rose Window

Reconstructed using parts of the original, the rose window softens the façade’s rather severe aspect, but unfortunately lets in only a limited amount of light.

Rose Window

2.Bell Towers

These stocky towers – defining features of the Sé – recall those of Coimbra’s earlier cathedral, built by the same master builder, Frei Roberto. A taller third tower collapsed during the 1755 earthquake.

The distinctive bell towers of the Sé

3.St Anthony’s Font

Tradition has it that Fernando Martins Bulhões (later St Anthony) was baptized in this font, which now features a tile panel of the saint preaching to the fishes. He is also said to have attended the cathedral school.

4.Treasury

The first-floor Treasury is a museum of religious art, with some important holdings. It lost its greatest treasure, the relics of St Vincent, in the 1755 earthquake.

5.Gothic Ambulatory Chapels

The Chapel of São Cosme and São Damião is one of nine along the ambulatory. Look out for the tombs of nobleman Lopo Fernandes Pacheco and his wife, Maria Villalobos.

Tomb of Lopo Fernandes Pacheco

6.Cloister

The Gothic cloister, reached through one of the chapels, was an early addition to the cathedral. Some of its decoration anticipates the Manueline style – notice the varied patterns of the oculi.

7.Romanesque Nave

Little remains of the original cathedral beyond the renovated nave. It leads to a chancel enclosed by an ambulatory, a 14th-century addition.

Romanesque Nave

8.Capela de Bartolomeu Joanes

This Gothic chapel, sponsored by a wealthy Lisbon merchant in 1324, contains the founder’s tomb and a 15th-century Renaissance retable, painted by Cristóvão de Figueiredo, Garcia Fernandes and Diogo de Contreiras.

9.13th-century Iron Railing

One of the ambulatory chapels is closed off by a 13th-century iron railing, the only one of its kind to survive in Portugal.

10.Archaeological Finds

Remains left by Moors, Visigoths, Romans and Phoenicians have been found in the excavation of the cloister.

Excavation of the cloister at the Sé

FINDS FROM LISBON’S PAST

Archaeologically, the Sé is a work in progress – just like the castle (for further details see Castelo de São Jorge) and many other parts of central Lisbon. All this digging means that an increasing number of ancient remains are being uncovered. Public information can lag behind archaeological breakthroughs, but make a point of asking – you may be treated to a glimpse of the latest discovery.