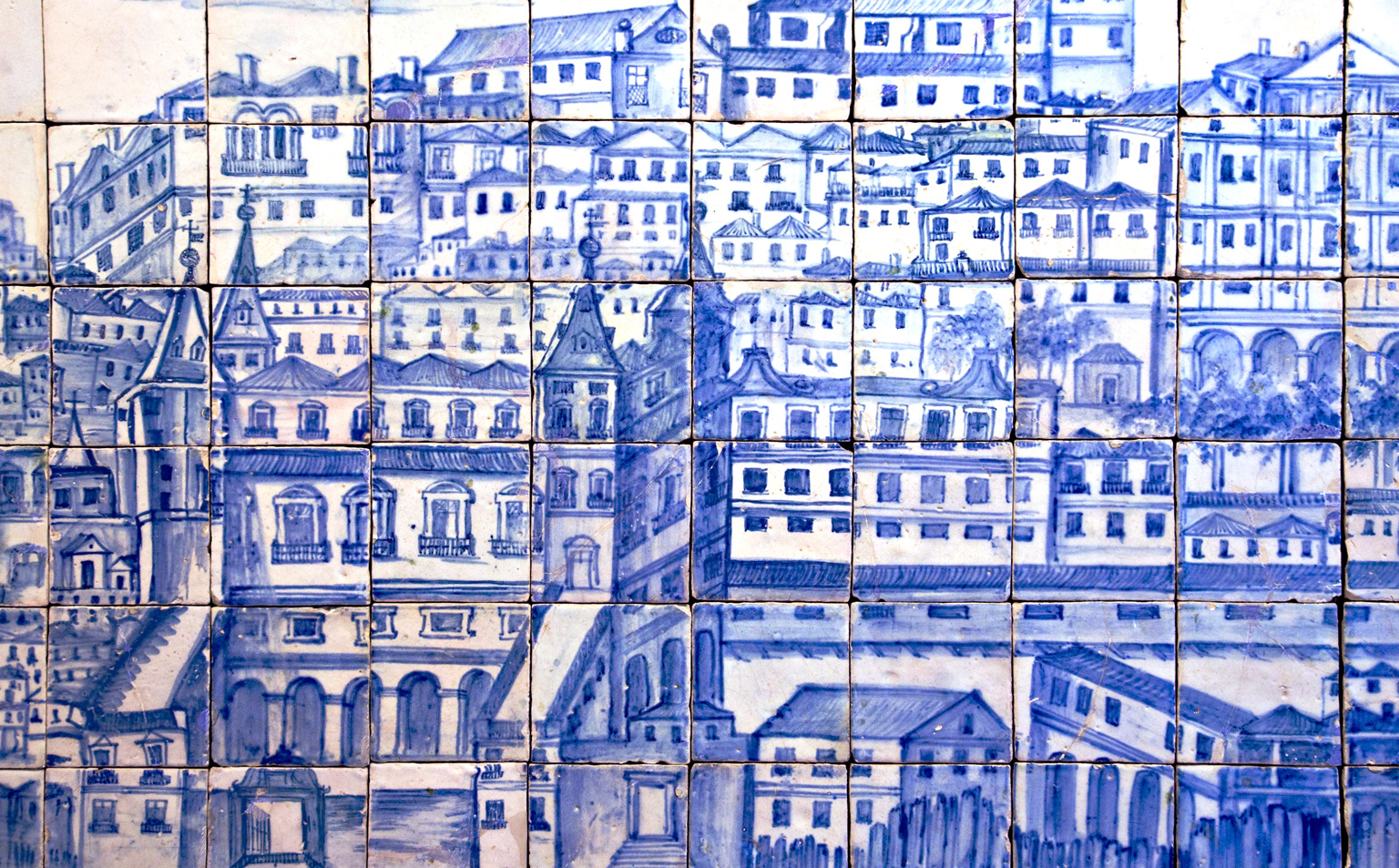

Ceramic tiles, or azulejos, are a distinctive aspect of Portuguese culture, featuring in contexts both mundane and sacred. The art of making them is a Moorish inheritance, much adapted – most noticeably in the addition of human figures, which Islam forbids. This museum dedicated to tiles is enjoyable both for the excellent displays and for its beautiful setting, a 16th-century convent transformed over the centuries to include some of the city’s prettiest cloisters and one of its most richly decorated churches.

NEED TO KNOW

Rua da Madre de Deus 4 • 218 100 340 • www.museudoazulejo.pt • Open 10am–6pm Tue–Sun • Closed 1 Jan, Easter Sun, 1 May, 13 Jun, 25 Dec • Adm: €5; senior citizens €2.50; Youth Card holders €2.50; under-12s free; free on first Sun of month

Rua da Madre de Deus 4 • 218 100 340 • www.museudoazulejo.pt • Open 10am–6pm Tue–Sun • Closed 1 Jan, Easter Sun, 1 May, 13 Jun, 25 Dec • Adm: €5; senior citizens €2.50; Youth Card holders €2.50; under-12s free; free on first Sun of month- The rather awkward location of the Tile Museum can be turned into an asset if you combine it with a visit to Parque das Nações, a shopping trip to Santa Apolónia, or lunch at D’Avis.

- The best place for a drink is the museum’s cafeteria; otherwise, head for Santa Apolónia.

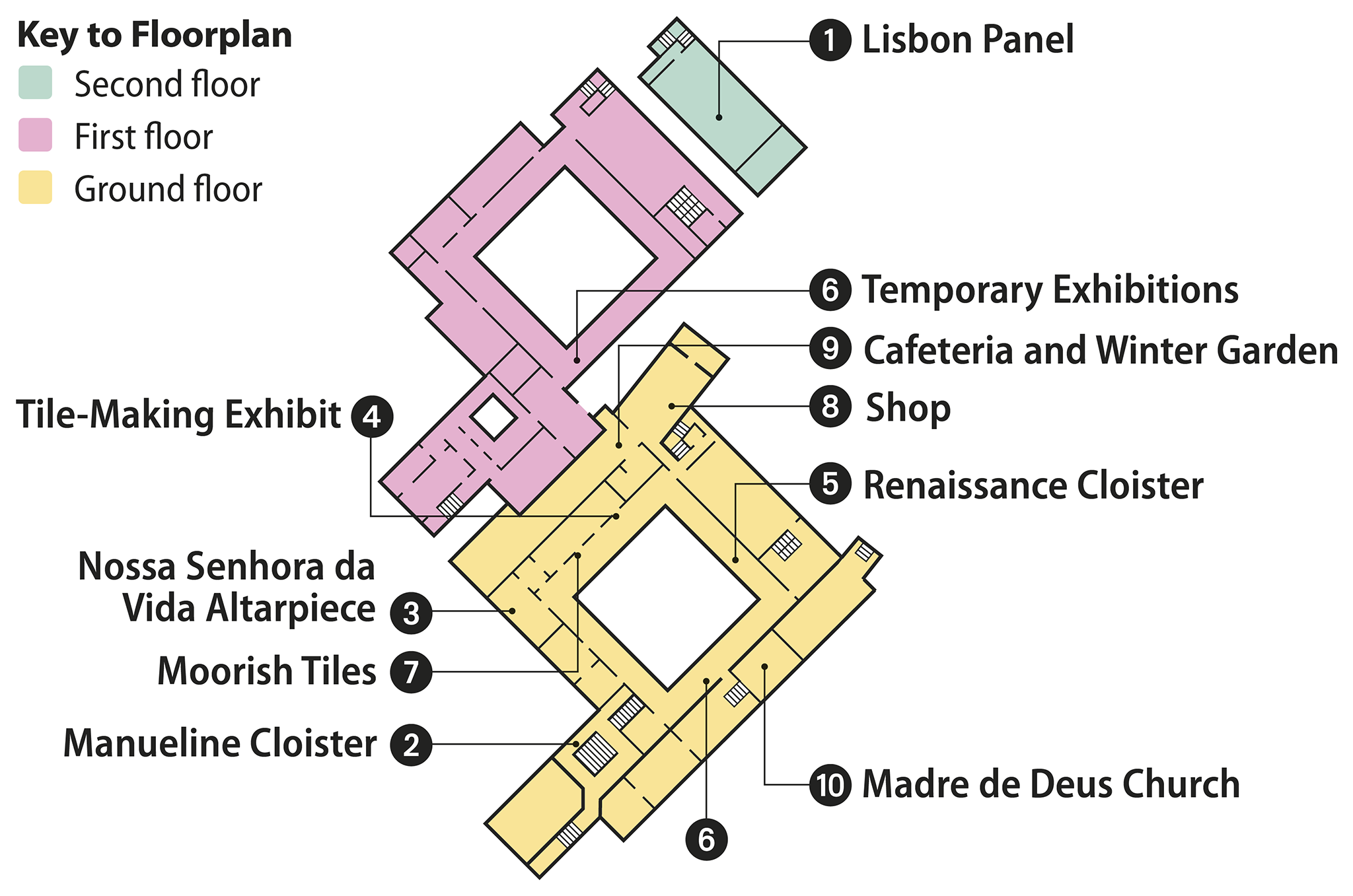

1.Lisbon Panel

This vast tiled panorama of Lisbon, 23 m (75 ft) in length, is a captivating depiction of the city’s waterfront as it looked in about 1740, before the great earthquake. It was transferred here from one of the city’s palaces.

Lisbon Panel

2.Manueline Cloister

This small but stunning cloister is one of the few surviving features of the original convent of Madre de Deus. This is the Manueline style at its most restrained. The geometrical wall tiles were added in the 19th century.

Manueline Cloister

3.Nossa Senhora da Vida Altarpiece

Almost 5 m (16 ft) square and containing over 1,000 tiles, this 16th-century Renaissance altarpiece is the work of Marçal de Matos. It depicts the Adoration of the Shepherds, flanked by St Luke and St John.

4.Tile-Making Exhibit

Step-by-step exhibits on tile-making, from a lump of clay to final glazing, illuminate how the medium combines the practical and decorative.

5.Renaissance Cloister

Part of the first major alteration to the convent in the 16th century, this airy, two-level cloister is the work of Diogo de Torralva. Glassed in to protect visitors and the collection from the weather, it is the light heart of the building.

6.Temporary Exhibitions

The ground and first floors have temporary exhibitions on subjects like contemporary tile art, an important art form in Portugal.

7.Moorish Tiles

With their attractive geometric patterns, varied colour palettes and glazing techniques, Moorish tiles continue to inspire tile-makers and home decorators alike.

Moorish Tiles

8.Shop

Numerous quality reproductions of classic tile designs are available, as well as modern tiles and other gifts.

9.Cafeteria and Winter Garden

Suitably tiled with food-related motifs, the museum cafeteria is worth a stop for coffee or a light lunch. The courtyard is partly covered and forms a winter garden.

10.Madre de Deus Church

The magnificent barrel-vaulted convent church, packed with paintings, is the result of three centuries of construction and decoration. Its layout dates from the 16th century; the tile panels and gilt woodwork are 17th- and 18th-century.

Interior of Madre de Deus Church

A NOD FROM THE 19TH CENTURY

When the southern façade of the church was restored in the late 19th century, the architect used as his model a painting now in the Museu de Arte Antiga. This shows the convent and church as they looked in the early 16th century. Indoors, the quest for authenticity was less zealous. In one of the cloisters, 19th-century restorers have left a potent symbol of their own era: an image of a steam locomotive has been incorporated into one of the upper-level capitals.