IN 293, even as Constantius and Galerius were taking up their new posts, Narses, the son of Sapor, the former king of Persia, rose up from his base in Persian-controlled Armenia and overthrew other claimants to the throne. Diocletian appears to have congratulated him on his victory—but this was scarcely enough to keep the peace indefinitely: three years later Narses attacked the Roman Empire.

The year 296 was a good one in which to launch an assault. In the west, Constantius was preparing for the final invasion of Britain. He would accomplish the destruction of the breakaway regime, now led by Allectus, who appears to have replaced Carausius, the “pirate” we met in chapter 4, after his defeat in 293. At the same time, a revolt had broken out in Spain, which attracted the personal attention of Maximian; he would then move to the Rhine in case the tribes north of the river should take advantage of Constantius’ departure for Britain to raid across the border. Trouble may once again have been brewing in Egypt where there had been a revolt three years before, related, it seems, to the reprise of open war between two communities that had also fought each other under the emperor Probus during the 270s. Galerius had dealt well enough with that revolt, but the rebellion that broke out in 297, which threatened the stability of the region as a whole was more serious. It involved some imperial officials proclaiming themselves emperor—a situation clearly requiring the attention of Diocletian.1 The Egyptian revolt meant that Galerius was on his own in dealing with the initial Persian attack.

Galerius’ most serious problem as Narses advanced along what was probably the route his father had taken in 260 was that he did not have enough men to resist the full force of the Persian army; and with campaigns raging in three other theaters there were no significant reserves at hand.2 Lacking enough men to resist efficiently, the outcome of the initial campaign was variously described as a disaster stemming from Galerius’ imbecility or a hard-fought series of ultimately unsuccessful battles. According to one tradition, in a review of the troops at the end of the campaign Diocletian forced Galerius to follow his chariot, which (if true) may have signified to the soldiers that their commanders were apologizing, demonstrating their determination to do a better job. It is possible that this most hostile account is not the most accurate, though, for the Persians seem not to have passed beyond the Euphrates, perhaps indicating that the Roman failures were not catastrophic. In 298 the war shifted to the Armenian highlands and here, where the cavalry that were the strength of the Persian army were less effective, Galerius scored a massive success. One story has him displaying considerable courage by scouting enemy positions in person. Narses’ army was routed and his harem captured. The Roman forces seem then to have crossed the Tigris, at which point the Persians allegedly decided to negotiate.3

The fate of Valerian appears to have been very much in the air in the lead-up to the campaign. Lactantius says that Diocletian used Galerius in command because he feared that if he didn’t he would follow Valerian into footstooldom; although the account may be false, Romans of Diocletian’s time largely believed the story of the indignity to which Sapor subjected Valerian. In a later account we are told that the Persian ambassador opened the negotiations with a reminder to the Romans that their two empires were the world’s great powers, and that it behooved neither to seek the destruction of the other. When he added that the Romans should be mindful of the changing fortunes of the world and not seek to press their advantage too far, Galerius blew up, pointing out, “Indeed you observed the rule of victory towards Valerian in a fine way, when you deceived him through stratagems and took him, and did not release him until his extreme old age and dishonorable death. Then after his death, by some loathsome art you preserved his skin and brought an immortal outrage to the mortal body.”

The outcome of the Roman victory was perhaps more modest than might have been expected, given the rhetoric of revenge on the Roman side. The principal Roman demand was that Persia surrender control of five regions on the east bank of the Tigris in the area leading north into Armenia, which, having been dominated by the Persians in recent years, was now securely relocated in the Roman camp. The rulers of all these lands were expected to act in Rome’s interests. The other demand was that trade be controlled through the city of Nisibis at the eastern edge of the Roman province of Mesopotamia. This move effectively recognized shifts in trading patterns arising after the destruction of Palmyra in the 270s. That city had controlled trade from India, through lower Mesopotamia and across the desert to Syria. It appears that Narses got his harem back.4

The new model Roman army had proved its worth. Its main tactical units included more cavalry, some light horse for scouting and harassing enemy units or pursuing the defeated, plus other heavily armored units on the model of the extremely effective Persian heavy cavalry, and smaller, more lightly armed infantry units. The typical Roman infantryman was now protected by a large shield, a bronze helmet and a leather chest-protector in place of the chain mail or segmented iron of earlier periods, and he preferred a lance to the javelins and short swords fundamental to former legionary tactics. Impressive as the triumph had been, it is striking that in the wake of the great victory, Diocletian avoided any move that would have required him to enlarge the army, which would have happened if he had chosen to garrison new territories taken from Persia. The vastly increased number of units that appear in the record from this time forward represent not a significant increase in the overall manpower of the military, but simply a different manner of deployment, just as the much smaller forts that come into being at this point along the Rhine and Danube reflect a tendency to deploy fewer troops on the frontier and more in positions from which they could react to rumor of invasion passed along from the forward defenses.5

It is in the wake of the twin triumphs over Persia and Allectus that we get complementary glimpses of the two Caesars, one in the words of a panegyric delivered immediately after the reconquest of Britain, the other in the spectacular sculptural decoration of Galerius’ palace at Thessalonica. In the words of an orator or at the hands of a sculptor, the messages are remarkably consistent, drawing attention to the linkage between the rhetorical and plastic arts in shaping the outward image of the imperial college.

The speech to Constantius opens, as so often, with a confession of the orator’s inadequacy for his task—this one is a retired imperial official who could recall his subject’s successes as a general in the early years of Maximian’s reign—and with a reminder that Constantius is there in the hall with them. Constantius, the speaker goes on, experienced a divine rebirth when he was selected as Caesar; his promotion in the spring chimed in with the rebirth of the world. The reason that the emperors needed two new Caesars was simply that the world was too big to be run by two men; there were too many places needing to be visited too often. Appointing two new emperors solved the problem and brought the imperial college into accord with nature: just as there were four elements and four seasons, so it was right that there be four emperors.6

Having explored the cosmic significance of Constantius’ elevation as he sees it, the speaker assesses his accomplishments in the context of those of his co-emperors: the victories over Sarmatians, the defeat of the Egyptian rebellion of 293, and the campaigns against Carausius. Constantius’ arrival (adventus) is presented as the beginning of victory—stress on the glory of the emperor’s advent is commonplace in a panegyric—with the capture of Gesoriacum (Boulogne), then more victories at the mouth of the Rhine. The speaker conjures up images of the barbarians surrendering themselves to Rome, giving up their lands to farm in Roman territory. In this narrative the history of the previous decades collapses, so that it would seem that the new regime succeeds directly from that of Gallienus, a tendency that illuminates perhaps the contemporary interest in Valerian, Gallienus’ father and co-emperor. At this point the rhetorical flood hides the complexity of what Constantius was trying to do. As Philip II with his grand armada in 1588, or, more recently, Napoleon and Hitler discovered to their cost, England is not an easy place to invade in the face of determined resistance.

Constantius had every reason to fear determined resistance. The enemy fleet intact, there was a substantial army on the island—and Constantius was limited in the number of men he could bring with him. Logistical factors—the most important being the size of the available ports—restricted the number of men that Constantius could bring to about 20,000, which was probably a smaller army than that of his enemies. And those enemies had proven themselves dangerous adversaries in the past, by land and sea.

To overcome the obstacle facing him, Constantius had to be able to win the war waged in the shadowy land of spies. He had to be able to keep his intended landing place secret from the enemy; he needed to know where the enemy fleet would be, where their troop formations could be found. He would need to know what roads to take when he landed, and he would need to try and keep the enemy from destroying the province if it looked like they were going to lose.

Advance planning was everything, and Constantius planned brilliantly. He slipped past Allectus’ fleet to land his army in the south of England; he crushed his enemies on the road to London and occupied the city without a fight. It is tempting to see the massive hoard of nearly 4,000 coins plainly buried in the context of Constantius’ invasion that was discovered near Rogiet in Wales in 1998 and the one found in 2011 at Faye Minter in Suffolk with 627 coins of Allectus and Carausius as signs of the confusion and fear that his arrival brought to his foes. Constantine, now in his early teens, would most likely have been in Trier as news of his father’s victory arrived; he would also have been of an age to understand what he had done and how he had done it. Did his father also tell him of the old days with Aurelian, who had shown that the best way to end a civil war was with a careful mixture of diplomacy and violence?7

The panegyric on Constantius places his accomplishments within the spectrum of idealized imperial behavior—the courage of the emperor; the humiliation of foreign foes, and especially of their leaders; the successful transfer of populations and the unity of the new regime with the natural world. These were themes that could be taken up in art as well as in words, and it is through art that we may perceive the way that Galerius was now being seen.

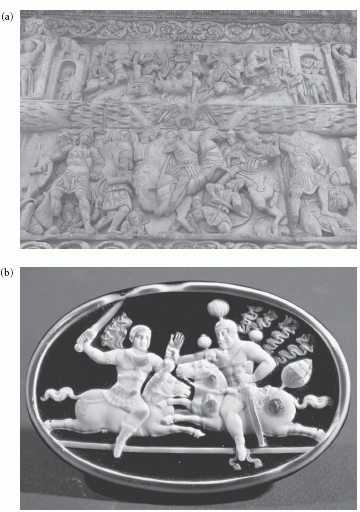

Our evidence for Galerius comes from the piers of two arches belonging to what was once an octagonal structure leading into a palace (see figure 6.1). Carved on four of the inside walls nearer the palace itself are images referring to Galerius’ campaign and on the outer panels more general images of imperial power. Proceeding from the outside in, the first inner panels depict specific events, then farther out are others illustrating the broader concept of victory in the east—the overall impression suggesting that Galerius’ triumph was but one episode in an ongoing tale of conquest. On the first of the campaign-specific piers are three panels: one showing a cavalry charge, another the capture of Narses’ harem, the third the Roman advance across the Tigris. The fourth panel depicts animals in such a way as to suggest that even the natural world is an enthusiastic witness to the glory of Rome. The neighboring panels show the final battle, the submission of the barbarians and the imperial adventus ceremony, then more animals. Opposite are depictions of another imperial adventus, personal combat between Galerius and Narses, who, as he is unhorsed, looks rather like a Roman general, the Augusti on their thrones flanked by the Caesars (Diocletian appears somewhat larger than Maximian) and a procession of Victory goddesses.8

FIGURE 6.1

Arch of Galerius in Thessalonica was once the entrance to his palace as seen in the reconstruction in (a). As a visitor entered the palace, he or she would literally be surrounded with images of imperial victory and the ideology of the regime including the relationship between the emperors and the gods and the all-encompassing reach of imperial power. Source: © Shutterstock.

The image of Galerius’ fight with Narses is striking not simply as confirmation that Roman generals were expected to lead from the front but also because it echoes Sasanian art in which the king is depicted in personal contact with the enemy—one surviving example shows Sapor unhorsing Valerian (see figure 6.2). On the outside panels of the first pier we find the emperor dispensing mercy, personifications of Persian cities, and more animal processions, while on the outer side of the second pier are portrayals of the abstract qualities of victory in the east, the virtue of the emperor, and a triumphal procession. Roma, the divine manifestation of Rome, is accompanied by victory goddesses, one of them carrying a commemorative shield, then more animals. Roma represents here the idea of the Roman Empire rather than the city itself: where the image of Roma does represent the city she is shown in the company of other great cities—a forceful statement on the part of Diocletian and his colleagues that the center of the empire was no longer that one city in Italy that had been the formal seat of their predecessors’ power.9

It is perhaps difficult to overemphasize the importance of the year 298 for imperial morale. Finally, after years of internal strife and uncertainty as to whether Rome could successfully deal with the full force of the Persian Empire, the questions had been satisfactorily answered. The last internal rebels, in Egypt and Britain, were dead, and Persia had been badly beaten. The new regime had justified its own pretensions and ousted Aurelian as the reputed restorer of the Roman world. Aurelian was not alone, of course, in having his role redefined: beyond the language of panegyric there is no more significant illustration of the importance of the regime’s historical revisionism, and increasing sense of superiority than Arcadius Charisius’ history of the praetorian prefecture.

In Charisius’ account, praetorian prefects were appointed in place of masters of horse who had been assistants to people holding the office of Dictator, the all-powerful magistracy of the Roman Republic whose role Julius Caesar had transformed in the last years of his life (49–44 BC) into the foundation of his power as head of the Roman state. The result was that

when the government of the Roman state was transferred to permanent emperors, praetorian prefects were chosen on the model of masters of horse by the emperors, and greater power was given to them for the improvement of public discipline. From these swaddling clothes the authority of the prefects has deservedly expanded so greatly that it is not possible to appeal from the praetorian prefects. Although there had previously been an open question whether, in law, an appeal was possible from the praetorian prefect, and there existed examples of those who had appealed, the right of appeal was later rescinded by an imperial statement read out in public. The emperor believed that those men who had been brought on account of their singular industry and demonstrated faith and seriousness of character to the magnificence of this office would decide no differently in their wisdom and light of their dignity than he himself would decide.10

FIGURE 6.2

The victory of Galerius over Narses is represented by this scene in which Galerius is shown unhorsing the Persian king. The image here is evocative of Sasanian imagery represented, for instance, on the great Cameo showing Sapor’s capture of Valerian and represents the assertion that Rome had now reversed the verdict of 260. Source: Mike Leese. Photo (Cameo): Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

In fact, the office of praetorian prefect had nothing whatsoever to do with the earlier master of horse, and to say that it had is no more than an antiquarian fantasy intended to prove that contemporary institutions had existed since the earliest time. There’s nothing new in that, but what is novel is the idea that the emperor would state that, at least in the context of the legal system, an official should be a clone of himself. Given this understanding of his role, the prefect, at least in theory, was responsible for the integrity of the empire’s day-to-day administration—the meaning of “public discipline” in this passage—and this too resonates with the spirit of the new codes whereby his lawyers represent the emperor himself in setting guidelines by which people should deal with their problems. The self-righteous self-confidence implicit in Charisius’ statement would become an ever more pronounced feature of Diocletian’s regime in the years after the Persian war.

As Diocletian’s regime entered a new phase, so too did Constantine enter a new phase of his life. We can’t be sure when it was, but already by 297 he may well have left his father’s court and moved to Diocletian’s. In one of the few autobiographical statements that survive from his own pen, he would later say that in his youth he had seen both Babylon and Memphis. It may be that the reference to Memphis means he was with Diocletian when he suppressed the Egyptian rebellion, though there would be another opportunity to visit there with him a few years later; the reference to Babylon should mean that he saw something of the last phase of the war against Persia.

Constantine was now in his mid to late teens, an age when young Romans of good family left home for places of higher education, and at home the palace was filling up with the offspring of his father’s marriage to Theodora. In the end they would have six children: the sons were Flavius Dalmatius, Julius Constantius, and Hannibalianus; the daughters are known to us as Constantia, Anastasia, and Eutropia (Anastasia, an overtly Christian name commemorating the resurrection, is unlikely to have been the name of an emperor’s daughter at birth).11 Constantia, the oldest of the girls, would be of marriageable age by 313, and Eutropia may have been the youngest.12 Anastasia was felt to be marriageable in 316. The fact that none were married before their father’s death in 306—and, indeed, for some time after that—suggests rather strongly that their births fall between 295 and 306, or in the case of Constantia and Anastasia between 295 and 300. Although Constantine’s relationships with his stepbrothers and sisters would prove important in later life, the chance to leave his infant siblings and seemingly perpetually pregnant stepmother behind may have been something of a relief.

When he reached court, Constantine would have continued his education in Greek and Latin when not accompanying Diocletian on campaign. He may have had a private tutor (if so, that person is unknown to us), but, on the rare occasions when the court was resident at Diocletian’s preferred capital of Nicomedia, he may have sought out the city’s leading professor of Latin. This man was of North African extraction with a broad knowledge of Latin letters, especially of the classical period—he knew Virgil very well, as would any well-educated person of the time, and was deeply interested in what he perceived to be the imminent end of the world. This man was Lactantius.