THE YEARS THAT CONSTANTINE spent at Diocletian’s court saw radical efforts by Diocletian and Galerius to reform the empire—efforts that were largely unfruitful. Did observing this futility that would unfold in the years after the great triumph over Persia have an impact on Constantine? We cannot know for certain, but we do know that when his turn came to rule the Roman world he did not attempt to emulate Diocletian. Perhaps by then he had learned the limits of imperial power. He would certainly learn a great deal about how government worked, about how to deal with the people who worked in large institutions and about the art of war. He would show a precious mastery of all these areas when he took power for himself in his mid-twenties. He would also fall in love.

Late imperial courts were more than the massive building complexes where emperors and subjects could communicate with each other. They were vibrant communities in their own right, bringing together diverse individuals and agendas of all sorts. They were also mobile, and although Lactantius claimed that Diocletian was trying to build up Nicomedia as a new Rome, the emperor was rarely there during the years that Constantine was at court. Constantine tells us that he saw Memphis and Babylon in his youth, so he must have joined the court where it was most often located in those days: on the road. Diocletian was in Egypt from 297 to 298, in Syria to support Galerius’ operations against Narses by February 299, and residing most often at Antioch, though he would go as far east as Nisibis, a powerful fortress just to the east of the Tigris to complete the peace negotiations with Persia. Last attested at Antioch in July of 301, the court appears to have headed off again later that summer for Egypt, where it remained until 302. It was back at Antioch by the autumn of 302 and in Nicomedia from the end of 302 through March 303, at which point Diocletian and his entourage made the long, slow journey to Italy. Although he would fall desperately ill in Rome in December of 303, he again took to the road, making his way back to Nicomedia. It was there that he would end his reign on May 1, 305.1

To be a courtier of Diocletian was to be a traveler, and while some cities were equipped with the infrastructure of palaces and all that went with them, court life was not the same as palace life. Court life involved participation in a hierarchically organized community that could function as the effective government of a great empire at whatever point it might stop for the night.

The court, or comitatus, of Diocletian included people ranging from transport personnel, soldiers, cooks, and domestics of all sorts to the great ministers of state and those who served them.2 The military escort appears, in Diocletian’s time and in his particular entourage, to have consisted of recently raised units of the imperial guard, both infantry and cavalry, including horse archers and heavily armored cavalrymen.3 This escort amounted to about 3,000 men, enough to provide security but not enough for a decisive military intervention. There would also have been a corps of young “officers in training” or protectores (guardians), in whose company Constantine would have moved. When the bureaucrats and servants are added into the equation, it appears that the traveling court numbered some 6,000 persons.

At the time Constantine arrived, two of the leading ministers were Hermogenianus, the author of the great code of the 290s and now praetorian prefect, and Sicorius Probus, who apparently had overall charge of foreign affairs. Also present would have been whoever held Hermogenianus’ old job overseeing responses to petitions, as well as the man in charge of the emperor’s official correspondence and two finance ministers. One of these financial officials, rationalis rei summi (accountant of the highest account), controlled the mines, the mints, and the collection of taxes in cash, while the other, the magister rei privatae (master of the private account), ensured that money continued to flow in from the rents of the vast properties that passed from one emperor to the next, and that all property that should come to the emperor—such as property for whom no owner could be found, or in the form of gifts—was duly received by him. There would also have been the praepositus and his staff. The praepositus, or “stationed official,” worked in very close proximity to the emperor, minding his bedchamber and wardrobe. He would have been a eunuch, possibly from abroad since castration was technically illegal in the Roman Empire, even though the ban was not necessarily enforced. Law tended to give way to utility in the Roman world and doctors were familiar with modes of transforming a healthy male into a eunuch. According to one expert:

Since we are at times compelled to castrate against our will by persons of high rank, we will briefly describe the method of doing it. There are two ways to do it, by compression and by incision. The operation by compression is performed this way: children of young age are placed in a vessel of hot water, then, when the body warms, in the bath, the testicles are squeezed with the fingers until they disappear, and, being dissolved, can no longer be felt. The method by incision is as follows: let the person to be castrated be seated upon a bench, and, with the fingers of the left hand grasp the scrotum with the testicles and stretch them, making two straight incisions with the scalpel, one for each testicle. When the testicles appear they should be cut around and cut out leaving only the very thin bond of connection between the vessels in their natural state. This method is preferred to compression.4

Recompense for service at court was not especially lavish, something that may have made payments in kind (usually enough to feed an official’s entire staff and possibly with enough left over to sell if he wished) and exemptions from civic munera especially important to those who served. Our evidence on this point is not ample, but what there is seems significant: namely, that the remuneration of one senior official was set at 300,000 sesterces. The figure as a salary for a senior palace official had not changed in more than a century and was thus worth vastly less than it had been before the high inflation during Aurelian’s reign.5 The inelasticity of salaries in the face of inflation may have made the early fourth century a time when imperial service was not dominated by people much wealthier than those who served on the town councils of major cities, and it is interesting that a later reminiscence expresses approval that Diocletian encouraged a “better class” of official and eliminated those of bad character.6

Although close proximity to the emperor at private moments—and to the empress, who might travel with the court—made palace eunuchs potentially very powerful, by reason of their physical condition, they were not usually included in the most important meetings of the emperor’s inner circle, or consistatorium, so called because the members of this group would be standing (consistentes) throughout the proceedings. The fact that at a meeting of the consistatory, one person—the emperor—would sit while the others stood reflects an important aspect of the hierarchy within the palace and indicates how the various functions were defined according to their proximity to Diocletian. On a typical day, most people’s station in life would dictate their activity: cooks would cook, soldiers would drill, the financial staff would deal with their accounts, the legal staff would answer petitions. The emperor had no direct role in these activities, and it is unlikely that Diocletian was consulted about the private rescripts that went out in his name since they were not conclusive. He would have been directly involved, though, in cases where a matter could be settled once and for all. In such a situation he would consult with the most senior staff and hear embassies from important places. A passage has survived in the later Codes showing Diocletian doing just this. It concerns an embassy from Antioch. We are told that when certain leading men of that city had been brought into his presence—presumably intending to claim that certain categories of courtier should not receive immunities from public service—a man named Sabinus (probably an Antiochene, as he seems to have spoken in Greek) made a comment to which Diocletian responded (in Latin): “Freedom from personal and civic munera has been granted by us to certain ranks, these are those who have served as protectors and praepositi. They are therefore not to be called to personal or civic munera.”7

The response to this embassy does not show Diocletian’s manners at their best. He is abrupt, and the point he is making is that his government communicates in Latin (in previous centuries emperors had responded to their Greek-speaking subjects in Greek). On the other hand, it is worth noting that he is speaking in his own right, and to ambassadors who have been allowed to speak to him directly.

The incident demonstrates that manners at court were complicated, and that our ability to understand just how people might have interacted is often complicated by the later reflections of individuals accusing Diocletian of having introduced outrageous new habits that set the emperor apart from his subjects. Such perceptions say a good deal more about the way Diocletian was remembered than about how he actually behaved, but it is undeniable that changes in court ceremonial did take place, especially practices concerning entrances into major cities, which became far more elaborate so as to induce a new sense of awe. The question however remains: just how unprecedented were these apparent changes and what impact did they have on the daily business of government?

It appears that Diocletian’s interactions with his senior staff could be relatively informal. Lactantius certainly presents Galerius as speaking quite frankly to Diocletian; and at one meeting with Maximian, where only the two of them were present, Diocletian spoke very straightforwardly. Members of the emperor’s innermost circle were expected to know things that others did not, and it is very likely that their exchanges were unobstructed by the intense formalism that was rapidly becoming standard in other areas of court life. A further sign of a distinction being made between those on the inside track and others are texts that identify certain very high-ranking people—praetorian prefects and the heads of the major bureaus of government—as consistatory companions (comites consistoriani).

Although members of the inner circle might speak their minds to the emperor, it does appear that membership in such a circle was far more limited than in earlier eras when emperors might invite members of the elite to weekend retreats or join important subjects for dinner. The ordinary person was now kept at a greater distance and forms of address that in earlier centuries might have appeared extreme or ridiculous—the satirist Lucian makes fun of people who see themselves as “more lordly than the others, expect worship to be paid them not from a distance in accord with Persian custom” who expect people to kiss their hands or breast—were now typical. Diocletian formalized behavior of the sort disdained by Lucian as a way of enhancing the impression of his magnificence, allowing only people of importance to be seen approaching him so that they could kiss the hem of the purple clothing that was now to be worn only by a member of the imperial college. How often was this ceremony performed with the traveling court? That remains unknowable, but it was not likely a feature of daily life. Such formal ceremonies are presented in the sources as something special and quite possibly were enacted only when the emperor entered a major city; they would also have the effect of showing off the important people in his train to those with whom they were staying.8

The young Constantine was a noticeable figure at court—Bishop Eusebius later claimed that he remembered seeing him pass through when he was with Diocletian, and Constantine’s memories of Diocletian appear to have been very powerful. So too were his feelings about the lives of his courtiers; later in life he would be solicitous of their well-being, and in his dealings with his senior officials he appears to have been quite open. Like Diocletian, he would often display signs of a powerful temper, but—and this seems to have been unlike Diocletian—he also seems to have been capable of backing down or changing his view of a person.9

Other, less spectacular behaviors associated with emperors were, no doubt, more common in the daily life of the court. These included the process of moving from place to place—although not every stopping point would be of sufficient importance to merit a formal entrance ceremony—as well as making public sacrifices to the gods, and going on hunting trips. We can obtain a unique insight into the impact of the court’s arrival in a new place from a collection of letters written by the official in charge of the city of Panopolis, the modern city of Akhmin, in southern Egypt in AD 298 about the time that Constantine joined the court, and it may well be that this correspondence preserves the earliest official documentation connected with Constantine’s career in the imperial service. Diocletian had passed by earlier on his way to deal with tribes beyond Egypt’s southern border, and, it seems, to see how the area was settling down after a revolt.

We may get some sense of how Constantine and other members of the court may have traveled the Nile in this year from the memoirs of Richard Pococke, an Englishman who journeyed down the Nile in 1737 and who describes for us “the great ships” with two masts, covered in matting supported “by means of poles set upright with others tied across the top, under which awning the passengers sit by day or repose by night.” Since Pococke was in a small boat and disguised for his own safety as a Copt, he seems envious of the leisure in which others could travel. In the late summer, when Constantine would have been on the Nile, the temperatures would have been in the nineties and any shade would no doubt have been welcome. What we cannot know is whether, in the vicinity of Panopolis, Constantine would have met the ancestor of the cult of the healing snake who in Pococke’s time was believed to be a former sheik, whom “God, out of a particular regard” transformed into “a serpent, which never dies, but is endowed with the power of healing diseases and conferring favor on its votaries.” Pococke suspected that the cult had roots in much more distant antiquity than his informants could have known.10

The person who provides a sense of what it was like to have the court come to town in Diocletian’s time was Panopolis’ strategos, whose name was probably Apolinarius. The title strategos, the Greek word for general, had been used for local administrators in Egypt ever since the arrival of Ptolemy I, Alexander the Great’s general who had taken Egypt over after Alexander’s death in 323 BC. Ptolemy and his heirs had superimposed a Greek administrative system on the existing Egyptian structures, and it is this that lends the massive documentation surviving on papyri its particular flavor. Here we find practices dating from the time of the pharaohs before Ptolemy mingled with the latest in Roman administrative wisdom; and Greek mingling with what was now becoming the standard form of written and spoken Egyptian: Coptic, a language descended from that of the common folk who had served the pharaohs and survives to this day in Egypt’s Christian communities. The strategos, despite his military-sounding title, was not at all a soldierly figure, although he was responsible for the maintenance of public order in his town. When not dealing with miscreants, the strategos (who inevitably came from a neighboring district) had the difficult task of mediating between the needs of the people he was overseeing and the demands of the imperial government—a classic mid-level functionary trapped between the often idealized vision of the way things worked that existed in the minds of his superiors and the stubborn irascibility of the people he was supposed to manage.11

From the correspondence (known from a long papyrus roll) which opens on September 11, 298, it is clear that preparations for the court’s arrival have been going on for some time and that Aurelius Isidorus, the procurator of the province—Lower The baid—in which Panopolis was located, was getting increasingly anxious. It would be he who would presumably have to answer to officials at court if things didn’t go well. In late July or early September the strategos had written to local officials about the need to appoint people who would ensure that food and other necessities were provided. A second letter refers to a communication from Aurelius Isidorus about the provision of ships needed to transport necessities for “the arrival of our lord the ever-victorious emperor Diocletian senior Augustus.” The third letter appears to deal with the difficulties of getting people to heed Isidorus’ instructions. This letter, which the long-suffering official appears to have signed using a date in the Egyptian month of Thoth, refers to unpaid taxes from some point in May “to the nones of August (August 5) in the consulship of Faustus and Gallus,” suggesting that Isidorus was getting his orders from higher up in the administrative chain, where people naturally used Roman dates, not Egyptian.12

Life appears to have become even more fraught for the strategos between the 11th and the 15th of Thoth as the town authorities evidently do not share the sense of urgency that is exercising him and Isidorus. Moreover, people connected with the court are starting to show up in the area. On September 13 the strategos, no doubt getting rather desperate, writes to a person of some local consequence (possibly the leader of the town council at Panopolis): “with regard to the supply of the annona [tax revenues collected in kind rather than cash] which have been ordered to be stored in various places in connection with the fortunate arrival of our Lord the emperor Diocletian the Senior Augustus, I have written you both once and a second time so that you will select receivers and overseers of provisions for the most noble soldiers who will be entering our city,” and still nothing is done. On the 19th the situation seems ever more dire. Finally on the 23rd it appears that people are at last beginning to cooperate.

The strategos, himself a new appointee, is trying to organize all this against the background of the recent suppression of a revolt by Domitius Domitianus probably connected with Diocletian’s order to reorganize the provincial tax system, and some of the ambivalence about Diocletian’s arrival, as expressed, perhaps, in the locals’ slowness in responding to the strategos’ requests may be connected with this. However, there is little or no evidence in any of the correspondence for anyone doing anything that can be directly associated with the revolt except possibly the issuing of the note about arrears in taxation earlier that year, and a note elsewhere about arrears for the previous year. Some officials, including Aurelius Isidorus, had been in office before the rebellion—we know this because he transmitted an edict concerning the tax increase that may have sparked the revolt—and he may have kept his job during it. Similarly, the leaders in the towns through which Diocletian would be passing had not obviously resisted the rebellion, nor, for that matter, had the troops, whose units are receiving full pay in documents datable to 300 and seem to be getting their full pay in 298 as well. In the 270s, Aurelian and the Palmyrenes had both set high standards of nonintervention in local affairs, and Diocletian was following suit.13 The strategos’ communication, taken as a whole, illustrates a crucial point that Constantine seems to have assimilated thoroughly by the time he left Diocletian’s court—that power at every level was something that needed to be negotiated.

The court’s journey to Panopolis, while stressful for everyone, enabled the center of imperial power to shift for several months to southern Egypt, and as a diplomatic act this may have helped facilitate the reintegration of the area into the empire.

The food that was being collected to supply the court as it passed through the Panopolis area was nothing special—largely local produce, which at this point meant wheat with which to bake bread. For Egyptians, bread was a staple. Their diet would also include a wide range of vegetables—lentils, beans, asparagus, turnips, cabbage, chickpeas—as well as fruits, fish, cheese, and various meats such as chicken, mutton, goat, and pork in various forms (including sausages). Menus for two dinners that would not have appealed to the local jet-set to be held in the Egyptian city of Oxyrhynchus read: “For dinner on the 5th: a Canopic cake, liver. For dinner on the 6th: 10 oysters, 1 lettuce, 2 small loaves, 1 fatted bird from water, 2 wings …” The diet that we recover from these documents is evocative of the Christmas feast to which Pococke says he was treated by the Coptic community in Akhmon/Panopolis, “chiefly consisting of rich soups, ragoos, pigeons and fowls stuffed with rice and roasted lamb.”14

While the basic diet seems, from these menus and other similar items, to be astonishingly consistent through the ages, at about this time there was one change of great cultural significance, arguably one of the more radical in Egyptian history: wine replaced beer as the alcohol of choice among the population as a whole.15 For the soldiers, who were also supplied by the strategos, their diet was most likely similar to that of the rest of the people, though the quantity of meat (especially pork) that would have been available for them to consume was a good deal greater. The farther up the court ladder one progressed, the chances are that the quantity and variety of meat consumed increased proportionally. This may have been linked with the hunting expeditions that were one of the great passions of aristocratic Roman life, and a pleasure long associated with the notion that the ruler needed to protect his subjects from dangerous predatory animals (especially the feral swine that are often presented as public enemy number one in the natural world).16

Hunting, in the aristocratic context, appears to have been organized along the lines of a major military operation. Two of the spectacular mosaics in the Roman villa at Piazza Armerina in Sicily—mosaics created in the lifetime of Diocletian and Constantine—portray massive hunts and give us an insight into an activity that may also be alluded to in the processions of animals adorning the Arch of Galerius mentioned earlier. The grander of the hunting mosaics is to be found in the “transverse corridor” that runs for sixty-five meters between the villa’s audience hall and the inner courtyard, known as the peristyle court because it is surrounded by colonnades. The corridor terminates at either end in a rounded apse, the northern one offering a mosaic showing the female personification of Africa; the southern one shows the female personification of Armenia or India (the mosaic is too badly damaged to allow certainty).17

The composition that runs between the two apses is also of interest to us. It falls into three parts. At the northern end, hunters (who are obviously soldiers) are trapping African animals in a variety of ways. The central panels show animals being transported to what is plainly intended to be Italy, while the southern end has images of animals captured from elsewhere. There is good reason to think that the soldiers shown as engaged in the hunt are closely connected with Maximian, while the owner of the house, who must have been an important court official, probably figures in the transportation scenes. There are occasional scenes that show humans killing or being killed by animals, but the principal message from these mosaics is about the collection of animals for Rome, and especially, Rome’s control over the natural world, from the west coast of Africa to the farthest eastern boundary.18

The second, much smaller mosaic, located in a nearby room, is more conventional, dividing the action into four registers. In the top register huntsmen are heading out to hunt rabbits; the second panel centers on a sacrifice scene, with more scenes of rabbit hunting. The third register shows falconers on one side and a horseman spearing a rabbit on the other; the bottom register depicts people chasing gazelles into a net, while on the other side hunters engage with a boar. Here the most powerful message that comes across to the viewer may be the socially unifying aspect of the hunt—the humble rabbit hunter is engaged in the same operation as the master of the house, each in his proper role. The hunt in this sense is the peacetime extension of military service.19

The personifications in the apses of the great hunting mosaic at Piazza Armerina and the depiction of the man sacrificing in the lesser one serve to underscore the important notion that humans are acting on a stage laid out before the eyes of the gods. So it was that one of the emperor’s most important functions was to consult with them before undertaking any deed of importance. The usual way of doing this might be through animal sacrifice or by consulting an oracle.

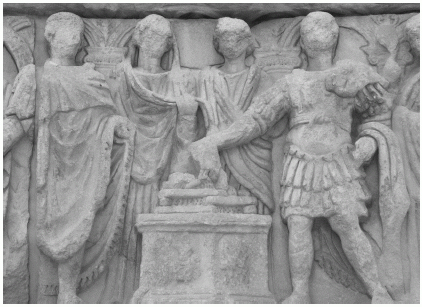

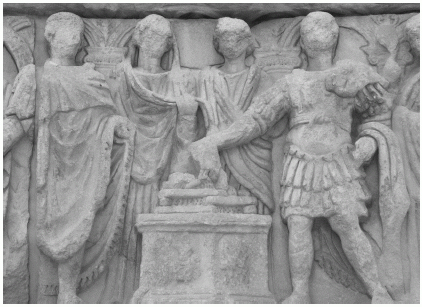

All animal sacrifice, especially public animal sacrifice at which the emperor presided, was a very formal event at which a god was invited to demonstrate approval for the action of humans by agreeing to share a meal with them. The ideology informing these sacrifices, as depicted, for instance, on the triumphal arch of Trajan at Beneventum, focused on the role of the emperor in ensuring that the relationship with the gods remained intact. Here he stands in front of a group of garlanded officials, presumably fellow priests—the emperor always held a number of priesthoods, including that of pontifex maximus, or chief priest of the college that was charged with overseeing religious ceremonies—the whole representing the commingling of civil and religious roles that had been typical of Greco-Roman culture for at least a millennium by the time Diocletian took the throne (see figure 7.1). These officials would have marched in the procession ahead of the attendants who accompanied the sacrificial beast to the altar. The emperor is pouring an offering (wine) from a small dish on to a small altar. A young boy stands next to him, holding a box containing incense that the emperor will offer once he has emptied the dish of wine. The eyes of all the priests are on the ruler, symbolizing the belief that the person making the sacrifice will (or should) determine whether the gods will be happy. Before the sacrifice actually began the emperor would have offered up a prayer to the gods, a rite clearly described by the Elder Pliny:

FIGURE 7.1

Diocletian sacrificing as seen on the arch of Galerius. Source: Mike Leese.

It does not accomplish anything to sacrifice victims without a prayer, and it is not the right way to consult the gods. Furthermore, there is one form of words for asking an omen, another for averting one and another for commendation. We see that our highest magistrates address the gods with fixed prayers; that to prevent a word being left out or spoken in the wrong place, one person reads it out first from a script, another person is posted to keep watch, a third is given the responsibility to see that silence is maintained; and that a piper plays so that nothing but the prayer is heard.

Once the prayer was said and the burnt offering made, servants, usually slaves belonging to the state, would prepare the animal (on the Beneventum relief, it is a bull); although Romans of a certain class might hunt animals in the wild it was not thought fitting for them to engage in the menial task of butchering. This was done after the animal had had a piece of hair snipped from its forelock in the expectation that it would seem to nod its head—its agreement to being eaten was seen as useful—before being stunned with a hammer. Its throat would then be cut.

Once the animal was slaughtered, it would be cut open so that its innards could be inspected. If there was anything out of the ordinary to be seen, the sacrifice would be called off or the process repeated until it became clear that the gods were in fact well disposed. At this point it seems likely that a sacrifice at which Diocletian was present would include the official inspection of the entrails by a priest, or haruspex (pl. haruspices) trained in the art of divination from animal guts (and other natural phenomena). Then the innards would be placed on the altar, to be burned as the god’s part of the meal. As soon as the animal could be butchered and cooked, the emperor and his priestly colleagues would settle down for their share of the food.20

All religious systems have active and passive aspects—the active involving the search for new revelation, the passive the repeating of actions that would seem to ensure the continuing goodwill of the gods. Sacrifice was a crucial moment at which the active and passive features of a cult came together. The ritual leading up to the sacrifice tended to be carefully choreographed so that it conformed to earlier, successful sacrifices, but the moment of sacrifice was the turning point. The process might be interrupted by some natural phenomenon or unexpected noise, or the innards of the beast could be found to be not quite as they should; it was invariably a moment of tension, and when an emperor was the sacrificer, it was also a moment when his authority was open to question—most important, were the gods still on his side? Only the success of the sacrifice could reaffirm the truth. A consequence of this implicit tension was that Diocletian exploded, or so Lactantius says, on a day in 302 when a sacrifice failed:

Since he was, being fearful, an avid investigator of the future, he was sacrificing herds of animals and seeking the future from their entrails. Then certain attendants who were knowledgeable in the Lord put the immortal sign on their foreheads as they were standing by the fire, with this done the rites were ruined through the flight of the demons.21

Pagan belief was founded on the principle that the gods could be seen to intervene in human affairs through the predictions that they gave, either through approving sacrifices or through their oracles. People could go to see places where the gods were said to have been active—there was a site near Troy where what seems to have been a massive fossil was identified as the body of a giant killed in a primordial battle at the dawn of Jupiter’s reign over the gods, and Troy itself was chock-full of mementos thought to be linked with the Trojan war. In fact, any major city in the eastern part of the empire was filled with inscriptions commemorating predictions of the gods that had come true or enjoining rites upon the people of the city. Aurelian’s exaltation of Invincible Sun, when he claimed that the god had revealed his favor for Rome in the course of the final battle at Emesa, was a classic example of the active aspect of worship. According to Christian doctrine, which did not deny the possibility of miraculous events favoring its pagan neighbors, these wonders were not the result of a god’s action—there being only one god, in their view, and he was not interested in helping people who did not worship him—but rather the work of demons who delighted in confusing mortals with their wiles. These demons were important to Christians in other ways as well, for one of the things that true believers were good at doing was uncovering the false actions and the actual harm that demons could do.22

Having set the scene at the sacrifice, Lactantius goes on to say that the haruspices did not see the expected signs and insisted that the sacrifice be repeated. Still the signs were bad, and the head haruspex, Tagis, finally told Diocletian that there were bad people around whose presence offended the gods. Diocletian was outraged and ordered that everyone in the palace was to sacrifice—if they refused they should be flogged—and that military commanders should make sure that all their soldiers sacrificed as well.23

The story as Lactantius tells it is not without its problems. The name of the chief haruspex, Tagis, is Etruscan, and the name is somewhat generic for haruspices, looking to the region now known as Tuscany where this priestly art was born. Diocletian’s subsequent order was a traditional “Christian test,” used for centuries to find out whether someone accused of being a Christian actually was a Christian, based on the theory that no committed Christian would offer a sacrifice. This was the issue that had fractured Christian communities after Decius’ edict on sacrifices in 250. But by this point, Christianity having been legal for nearly forty years (hence the presence of Christians in the palace staff), it had plainly not been an issue recently. One might also wonder at the logic of Lactantius’ tale, implying as it does that Diocletian’s sacrifices ordinarily went off without a hitch, and by implication that the Christians in the palace did not see attendance at sacrifices as necessarily problematic.

The acts of a church council held a few years later in Spain include provisions for those who had held a duumvirate (essentially the position of co-mayor), holders of priesthoods of the imperial cults and of local priesthoods. If, for instance, a man holding a priesthood of the imperial cult (which he could be required to take on as a civic munus) offered sacrifice after having been baptized, the bishops ruled that he should not even receive the last rites; while a person who holds a priesthood of the imperial cult and sponsors a munus—in this case the word “gift” means a spectacle including beast hunts, gladiators, and quite often the execution of condemned criminals in horrific ways—but did not sacrifice would receive last rites after doing penance. A catechumen (a probationary member of the Christian community) could be baptized within three years of having held his priesthood. A duumvir could not receive communion during his year in office, while ex-priests, even if they continued to wear the wreaths they had worn in office could be admitted to communion within two years of holding office so long as they did not sacrifice.

From these rulings it is clear that Christian leaders were trying to reconcile their faith with the practical necessities of living in a pagan society and with the obligations of the church’s wealthier members to their wider communities. Another ruling, that people who were killed attacking statues of the pagan gods could not be entered onto the list of martyrs, was plainly intended to dissuade Christians from provoking the pagan community, stressing that those who brought trouble down upon themselves deserved no honor.24

The decision concerning martyrdom was a profoundly controversial one, for some members of the Christian community believed that they should minimize dealings with the secular world and would most likely have been appalled by the rulings regarding Christians who held pagan priesthoods. The scene that Lactantius paints at court illustrates precisely the sort of trouble that extremists could cause for their fellows, and while he spins the story against Diocletian, he elsewhere admits that people should not seek martyrdom. It seems likely that some incident at this time led to the expulsion of some Christians from imperial service—this much is confirmed by another contemporary witness, Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea—but it is not clear that an event like the one described by Lactantius, colorful though it might be, was actually the cause. Eusebius seems to have thought that a senior officer named Veturius talked Diocletian into taking action against the Christians.25

In sum, what Lactantius really tells us is no more than that sacrifice was an important court ritual and that in 302, Diocletian decided to expel from imperial service Christians who failed a sacrifice test. In fact, the year 302 seems to be an important turning point in Diocletian’s reign, for it is at this time that his regime becomes far more interventionist than hitherto.26