GOD, THE ARMY, MARRIAGE, and the bureaucracy: the matters that figure so prominently in Constantine’s legislation during the two years following his defeat of Licinius represent the four pillars upon which he felt his regime stood. God had brought him victory; along with his army, he needed the imperial bureaucracy to govern; and he wished to rule an ordered society in which people knew their place and the vulnerable were protected. In addition, he had committed himself to constructing a new capital; as it was being named for him, it was clearly envisaged as a grander place than the cities of his predecessors. Constantinople was not seen to be Rome’s replacement, but it would excel all other cities and be the focal point for those who aspired to a place in his service. In Constantine’s city would reside an aristocracy whose authority depended on their relationship with him.

A city that was to be home to a great emperor needed to look the part. It was funded by the money liberated from Licinius’ treasury and by a special tax, and as it took shape, there was no doubt that the city was going to be spectacular. The emperor himself may have carried out a second foundation ceremony in which he marked out the city’s boundaries on November 26, 328 (allegedly guided by the Christian God as he did so).1 According to theories of civic design current at the time, there was great interest in both civic kosmos (layout) and kallos (appearance). The city’s kosmos as a capital depended heavily on the development of the governmental district, while its kallos was enhanced by the display of public art, much of it ancient.

Constantine’s city centered on the embellishment of the Severan additions—the two emboloi, or colonnaded streets, which intersected near the baths of Zeuxippus, the Tetrastoön and the basilica; and the remodeled circus, or hippodrome, now fronting the imperial palace. The intersection of the emboloi was now marked with a massive tetrapylon (four-way arch) known as the Milion, a title that echoed the golden milestone in the Roman forum. The Tetrastoön was rededicated in honor of Helena, who had died in 328; she was buried in a mausoleum on the Via Labicana in a sarcophagus that may once have been intended to hold Constantine himself as it is decorated with images of soldiers defeating barbarians. The massive sarcophagus and the grand mausoleum (figure 29.2) are testimony—as is the commemoration of Helena in the new city—of the role she had played in her son’s life.

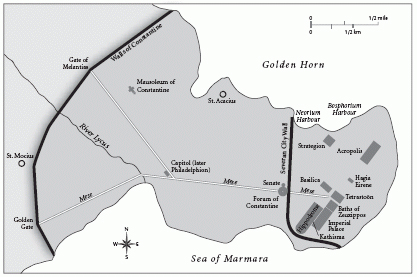

FIGURE 29.1

Plan of Constantinople. Source: After A. Tayfun Öner.

On the northwest side of the Milion, the old basilica was transformed into a square court surrounded by porticoes (a peristyle) to house several institutions including a library and two small shrines. One shrine was to the goddess Rhea, the mother of Zeus, identified here with the Magna Mater or Great Mother, one of the most prominent goddesses in western Turkey and worshipped as the mother of the gods. The other was to the Tyche (Fortune) of Constantinople, in the shape of a new goddess named Anthousa (in Latin, Flora; in English, Flowering) whom Constantine had brought in to replace Keroë, the old city goddess of Byzantium.2

FIGURE 29.2

The sarcophagus of Helena shows Helena on the right. The martial imagery on this monument suggests that it may originally have been designed to hold an emperor—surely Constantine himself. Source: Courtesy of the author.

The imperial palace rose to the south of the Tetrastoön, with its great entrance, the Chalke Gate, acting as the terminus for the embolos that ran south from the Strategeion. Its western edge was marked by the much-enhanced circus, to which it was joined through the Kathisma, or imperial box; the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara formed the palace’s southern and eastern limits as it spread out in numerous terraced pavilions and gardens.

The circus, on the model of the Circus Maximus in Rome, was transformed into a victory monument. Included in its decoration were statues of the ass and its keeper, evoking Eutyches and Nikon (Prosper and Victory), who had wandered into Augustus’ camp before the battle of Actium; these were imported from Nicopolis, the city founded by Augustus on the site of his victory. Other victory monuments were the Serpent Column, erected at Delphi after the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea in 479 BC, and an image of an eagle defeating a snake. This last image appears on coins issued in conjunction with Licinius’ defeat. The close proximity of the Licinian victory monument and the monuments to two of the defining military contests of the ancient world stressed Constantine’s place as history’s ultimate victor.

Other sculptures included famous figures of the past—Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, and Diocletian—as well as statues sent by other cities to strengthen their ties with the new capital. Miletus, for instance, sent a statue of its citizen Theophanes (an intimate of Gnaeus Pompey, Caesar’s rival for power) whose fellow citizens had voted him divine honors. From Rome came an image of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus; and there were also representations of wild animals, of Zeus, and two statues of Hercules. There was a giant masonry obelisk, which still stands on the site of the circus’ central barrier in modern Istanbul though its bronze covering has long since disappeared. It was placed there as a substitute: an authentic Egyptian obelisk like the one Augustus had put in the circus maximus at Rome, an object that Constantine had hoped to have, could not be transported in time.3

The great palace loomed behind the circus, and it is illustrative of the division between the public and private aspects of government that we do not know where, within this vast complex, the emperor had his private quarters, or where the individual bureaus of state were housed. All we know is that somewhere behind the great entrance was a house for Hormisdas, a Persian prince who had sought refuge with Constantine, and that some 6,500 people were employed within its walls.4

As the Mese, the city’s central east-west artery, passed through the old city wall it intersected with another forum, this one round and centered on a massive porphyry column from Egypt supporting a gigantic statue of Constantine (figure 29.3). This newer forum, known as the Forum of Constantine, marked the exact center of the city, and on its northwest side arose a new building to house the city council—in grand style. If the Forum of Constantine symbolized the linkage between the emperor and the governing class, a plaza a bit farther to the west along the Mese, known as the Philadelphion, commemorated Constantine’s family, perhaps with a bit of borrowed statuary since the famous porphyry image of the tetrarchs, now built into St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice, was originally housed here.5 One final monument of note, rising in the city’s northwest side near the new city wall, was a mausoleum. Intended as the future resting place of Constantine himself, this was a potent indication that there would be no abdication: clearly Constantine was not planning on leaving the city to molder away in some retirement palace destined to serve as his tomb.

The building program is emblematic of Constantine’s approach to government. He shows himself fully aware and appreciative of the traditions of the past while seeking to set those traditions in a fresh context. The displays of famous statues stressed the new capital’s appreciation of the traditions of other cities of the empire. The use of covered porticoes, emulating the cityscapes of Syria, showed that Constantinople was no imitation of Rome; indeed it may suggest that as Constantine traveled those lands in the train of Diocletian in his youth, they had made a powerful impression on him. The appearance of Diocletian in the circus and the porphyry representation of him with his three colleagues in the Philadelphion may also have indicated a new take on the old regime. In victory, Constantine could at last make peace with Diocletian’s ghost and proclaim his own regime as its legitimate successor.

Work on the city seems to have proceeded at a tremendous pace, so that by May 11, 330, it was ready for its dedication. We don’t know exactly what took place, but it appears that the festivities unrolled in two parts over two days. First there was a procession from the Philadelphion to the Forum of Constantine, which culminated in the placing of the great statue of the emperor on top of the porphyry column; the late sources mention prayers being said—not inherently unlikely, and so long as they were sacrifice-free, quite possibly inclusive enough to satisfy an audience used to acclamations of “the highest god.” The statue of Constantine was itself confessionally neutral as it was still a statue of Apollo, but with the head, displaying a radiant crown emblematic of the sun, now possessing Constantine’s features. In one hand it held a spear, in the other a globe supporting an eagle.

On the next day there was a procession in the circus, and the first chariot race was run in the revamped facility. Constantine wore a diadem set with pearls and other precious gems, recalling the words of Psalm 20: “You placed on his head a crown of precious stones.” He ordered that the baths of Zeuxippus be opened and evidently opened the palace to the public. An image of Constantine had been made in gilded wood, holding a statuette of Anthousa, the new city goddess, in its right hand. This statue was presented to the crowd in the circus and he ordered that on every anniversary of the city’s dedication it should be carried into the circus in a vehicle escorted by candle-bearing soldiers wearing cloaks and boots; after they had rounded the turning post at the far end of the track, the statue would be presented to the reigning emperor in his box. The focus this day was not on God but on the One (in the words of a contemporary poet) “whom god loves”—Constantine. It was his intention that it would remain that way.6

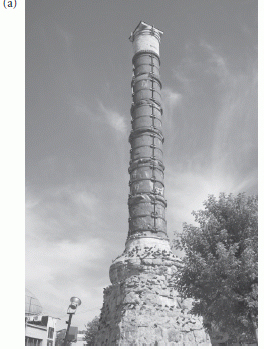

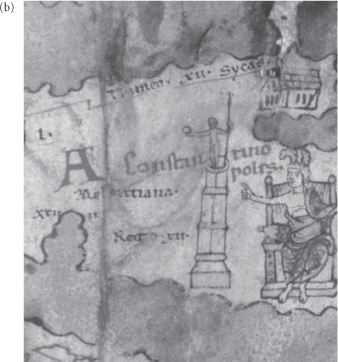

FIGURE 29.3

The image on the top is the great column of Constantine as it is today; the image on the bottom shows us what it would have looked like when complete and offers an image of Anthousa, the city goddess of Constantinople. Sources: (a) ©Shutterstock; (b) ©ONB Bildarchiv, Wien.

Although Eusebius would later depict the foundation of Constantinople as a thoroughly Christian undertaking and the shipping of statuary from around the empire as a deliberate insult to the gods, the opening-day ceremonies (which he does not describe) paint a different picture. Constantine’s regime was still largely non-Christian, and the active participation of non-Christians in shaping the city was clearly welcomed. Indeed, one non-Christian, Nicagoras, who prided himself on his role as the high priest of the ancient Mysteries at Eleusis, the immensely important rites that had been celebrated for more than a millennium in the vicinity of Athens, secured the porphyry column that played such a prominent role on May 11. We get a sense of his personality from two graffiti he left in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings while on his antiquity hunt: “The Hierophant of the most holy mysteries at Eleusis, the son of Minucianus, an Athenian, examined the burial vaults many years after the divine Plato from Athens, admiring them and gave thanks to the Gods and to the most pious emperor Constantine for giving me the opportunity.” Then on the wall opposite, he wrote: “In the seventh consulship of Constantine Augustus and the first consulship of Constantius Caesar. The Hierophant of the Eleusinian (Mysteries), Nicagoras, the son of Minucianus, an Athenian, examined the divine burial vaults, and admired them.”7

Given that one of Constantine’s aims was to unite his subjects at court, it would have been deeply unwise for him to let religion drive a wedge between them. Although the highest offices of state continued to be dominated by his traditional coterie, the court was now the prime instrument of political integration for those who, having (in theory) fulfilled their curial obligations, wished to climb the political ladder. So long as the aspiring official was of good moral character, he was welcome to join the imperial administration. Since the court would now be centered in the east where there were not many senators, Constantine would have to equate ranks in different parts of the service without making a man’s birth status a determining factor in his career.

In the new system, the praetorian prefects retained the rank of “most eminent man” (vir eminentissimus). Senior equestrian officials of the next rank, such as the praefectus annonae at Rome and the vicarii, attained the title of “most famous man” (vir clarissimus), once reserved for senators.8 Provincial governors, provincial military commanders, diocesan and provincial fiscal officials and the like retained the rank of “most perfect man” (vir perfectissimus).

At about the same time, Constantine regularized the position of imperial “companions,” or comites. The title of comes (the singular form of comites) had a very long history before Constantine’s time, with all manner of persons claiming or being awarded that title as a mark of status equivalent to the equally loosely applied title of imperial “friend” (amicus). At some point after Licinius’ defeat, Constantine formalized the order of comites, dividing it into three grades depending on level of service. This distinction was ultimately reflected in the transformation of senior titles such as magister rei privatae to comes rei privatae, which indicated that the actual power structure of the empire was court based.9

Restructuring his aristocracy, Constantine created a new sort of senate, a point lost on many later commentators such as a fifth-century ecclesiastical historian who wrote “he founded a great council and assigned to it the same offices and festivals as the old one at Rome.” In Constantine’s own time, one writer contrasted the old capital (advantageously as he saw it) with the new city on the grounds that Rome “has a very great senate, composed of rich men”; and the Descent of the Emperor Constantine states that “he even created a senate of the second rank there [in Constantinople], and called its members the ‘clari’ (famous).”10 The “senate” referred to here appears to be the city council of Byzantium, now enlarged and housed opposite the great porphyry column, whose members were eligible to hold a special praetorship so that they might join the clarissimi (most famous).11 Constantine further rewarded members of the Senate who chose to live in his city with houses and other privileges, in the same way that he rewarded important courtiers who resided in his company. The new body had the potential to develop into something more splendid, which it did, while offering no direct challenge to the ancient body at Rome. The contemporary poet Optatianus, ever adept at promulgating the official line, emphasized that Constantinople was the “second Rome” or “Rome’s sister.”12

The technical aspects of the creation of the new Senate, indicative of Constantine’s thinking, are less significant than the social and domestic implications. For instance, the new imperial residence adopted what must already have been the well-established pattern of shipping foodstuffs that had once been sent exclusively to Rome to other imperial seats. Also, the creation of a new power center in the east kept eastern dignitaries closer to home while also perpetuating a concentration of power in the senatorial aristocracy of the west. This represented a continuation of a pattern evident during the years after Diocletian’s abdication, when the hostility among his successors precluded movement from one court to another.13 Now the stress was (in theory) on ability and moral rectitude, qualities that Constantine was willing to reward with generosity. Eusebius wrote:

One who sought favor of the Emperor could not fail to obtain his request, nor was anyone who hoped for generous treatment disappointed in his expectations. Some received money in abundance, others goods; some acquired posts as prefects, others senatorial rank, others that of consuls; very many were designated governors; some were appointed comites of the first order, others of the second, others of the third. Similarly many thousands more shared honors as clarissimi or with a wide range of other titles; for in order to promote more persons the Emperor contrived different distinctions.

Those who later expressed contempt for Constantine told a very similar tale. Zosimus, writing in the sixth century, notes the impressive houses that he built for the senators who accompanied him to Constantinople, and others would complain of his excessive generosity to his supporters. The centrality of Constantine’s beneficence finds no better witness than in Julian’s panegyric for Constantius II, reflecting what was then the official line:

He [Constantine] showed such goodwill to his subjects that the soldiers remember his gifts and great-hearted generosity so that they worship him like a god.… When he became lord of the whole empire, there was a great lack of money, like a drought, stemming from the greed of the tyrant, and there was an enormous quantity of wealth collected in the corners of the palace, he ordered the doors unlocked, flooding the land with wealth.14

A contemporary voice, that of the poet Palladas, notes the connection between the shipments of statuary to the capital, the circulation of coin, and the luxurious surroundings of the imperial elite—was it to join them that he had come to Constantinople? Palladas writes in one poem: “The owners of Olympian houses, becoming Christian, dwell within unharmed, for the pot that makes life-giving folles [bronze coins] will not put them in the fire.” In another, writing in the persona of goddesses: “We Victories come, laughing maidens, bringing triumphs to the Christ-loving city. The ones who love the city created us, stamping figures appropriate to victories.” Here Palladas is probably referring to coinage that began to be issued in the 330s commemorating the inauguration of Constantinople. Both extracts appear to comment on the social world that was emerging in the new capital, one where new mixed with old and where a professional curmudgeon, as Palladas presented himself, could find much upon which to hold forth.15

The public statue collections at Constantinople could barely have begun to accommodate the mass of material that would have accumulated if all the cities of the eastern empire (and some few of the west) had shipped just a couple of treasures to the city. The best work went on exhibit. The less famous could perhaps be sought out in private settings, while other pieces went into the melting pot, as Palladas suggests. Somehow Constantine acquired enough gold, as a somewhat bilious critic of his expenditures implies, to mint vast quantities of gold coin, which would become the standard medium of exchange for major transactions over the next several centuries. The economic thinking, however, underlying his decision to do so does not seem to have been profound. What Constantine knew was that if he rewarded his followers lavishly, they would love him. And so, it seems, they did.

Constantine did not found Constantinople as a replacement for Rome but rather as a replacement for Nicomedia. His mother was buried in state outside of Rome; members of his extended family continued to live there, and Rome would be very important for his son Constans when he was emperor. Still, in the fullness of time, Constantinople would efface Rome as the political center of the Roman world and as the preeminent Christian city in the world until its capture by the Ottomon Turks in 1453. It is perhaps fitting that before this happened, a city whose foundation combined so overtly the symbols of the pagan past with the Christian future should be the primary vehicle for the preservation of Greek classical literature and classical civilization as we know it in the modern world.