THE VICTORY OVER LICINIUS at Chrysopolis in 324 did not bring peace on earth. Although details are scanty since they mostly come from changes in the list of victory titles that Constantine accumulated, we know that there was major trouble on both the Rhine and the Danube frontiers in 328–329. At this point Constantine built a massive stone bridge at Oescus (northwest of modern Pleven in Bulgaria) on the Danube, and he himself took the field along that river in 332, 334, and 336. On the first of these occasions he fought the Goths, who then dominated the eastern end of the region, and on the second he concentrated his attention on the Sarmatian peoples in the more westerly parts of the Danube basin. The campaign in 336 led to the proclamation of Constantine as Dacicus Maximus, a title deriving from the name of a people that no longer existed, the Dacians, and commemorated instead some territorial conquest north of the Danube in the area that Aurelian had abandoned in 271.1

Although he was chary about imposing his personal religious preferences on his domestic subjects, Constantine was far less reticent in dealing with his neighbors. So it was that when, in 336, the Goths elected to make peace, he agreed to the traditional terms—that the Goths send men to serve in the Roman army, and that the Romans would dispatch gifts to Gothic chieftains who demonstrated loyalty to the empire. Constantine would also take the opportunity to promote Christianity in their lands. To assist him in this he appointed a man named Ulfilas as bishop to their people. The descendant of people taken captive during the raids along the Black Sea coast of Turkey in the 250s and 260s, Ulfilas created a written form of the Gothic language into which he could translate scripture. In so doing, he planted in the minds of some Goths the notion that they (or their neighbors) might participate in Roman culture through religion rather than by the more traditional means through service in the Roman army. It is perhaps testimony to his success that Goths who did not themselves convert recognized in Christianity a threat to their traditional existence. And, although Ulfilas was driven into exile after Constantine’s death and ended his life ministering to a Gothic community within the empire, he left behind other Christians in the Gothic homeland.2

In the kingdoms of Armenia, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Iberia (roughly the eastern zone of the modern Republic of Georgia), Christian missionaries achieved more significant successes.3 Of these perhaps the most spectacular was that of the king of Aksum. Two boys, so the story goes, once slaves of a philosopher named Meropius, were the prime movers. One of them, Frumentarius, became the king’s chief adviser and gave Christian merchants particular trading privileges, which hastened the process of converting the young ruler. In time Frumentarius made contact with Athanasius and was ordained, while his companion returned to Roman territory where he too was ordained, becoming a priest at Tyre.4

The conversion of Armenia took place even before 324, when its king, Tiridates III, led the way by converting under the influence of the Cappadocian bishop Gregory the Illuminator in 313 or 314.5 Iberia, which stretched along the northern border of both the Roman and Persian empires, converted in the 330s, with the king leading the way under the influence of a rather mysterious woman whose faith enabled her to conduct miraculous cures.6 It was this woman’s activities that brought the church to the attention of the king, who converted, it was related, when he was rescued from a darkness that enveloped him in a forest while hunting. By the mid-330s Constantine was showing interest in the prospect of dealing a knockout blow to the Persian Empire, and appears to have been very pleased by these developments, sending aid for the construction of churches. For the king of Iberia, whose realm contained hitherto many Zoroastrians, the new faith was a powerful symbol of a new political affiliation. It may be that in this case religion proved a rather more successful vehicle for diplomacy than among the Goths, since the more organized society of the Iberians could be converted from the top down once the king himself had converted.

Constantine’s plans for Persia were aggressively pursued from the moment of his victory over Licinius. Optatianus suggests in some poems of the 320s that the Persians would soon be delighting in the rule of the western emperor; and it is quite likely that it was Constantine himself who sent a carefully crafted letter to Sapor II (a descendant of the victor over Valerian), who in 309 had acceded to the Persian throne while still in his mother’s womb.

Written at about the same time as his oration to the bishops, the letter combines contemporary propaganda with little touches aimed at a Zoroastrian audience. Knowing that Zoroastrians saw themselves as representing the forces of truth against darkness, Constantine began by proclaiming that, led by the light of truth, he had recognized the divine faith. His God was alone responsible for his present state of magnificence, having led him over land and sea to defeat tyrants, and bringing salvation to all people. “Him,” he wrote, “I call upon on bended knee, shunning all abominable blood and foul hateful odors, refusing all earthly splendor.” He is the God of the Universe who takes pleasure in “works of kindliness and gentleness, befriending the meek, hating the violent, loving faithfulness, punishing unfaithfulness.” He is also the God who “values highly the righteous empire,” strengthening it and protecting the imperial peace of mind.7

Having established what a friend he had in his God, Constantine moved on to the offensive. Those who, “seduced by insane errors,” attempted to deny the righteousness of his God had now been overwhelmingly punished—among them “that one, who was driven from these parts by divine wrath … and was left in yours, where he caused the victory on your side to be very famous because of the shame he suffered.” Hearing this variant, a Persian familiar with the usual imperial complaint about Valerian could not fail to note that it deprived Sapor of credit for the victory and attributed it all to Constantine’s God. He might also have noted how the memory of the year 260 still lived on in the Roman consciousness: the capture of Valerian and his ignominious treatment by the Persians was something that could never be forgotten—and if it could never be forgotten, could it ever be fully avenged? Moreover, Constantine pointed out, in his own day the punishment of those who persecuted his God was notorious, so Sapor would be well advised to make sure Christians were well treated in his lands. That would make the Lord of the Universe ever so happy.8

Constantine’s kindly thoughts carry a threat on two levels. One plainly is that the Christian God is a very fine god of battles, as recently proven by his own experience, and if the Persians don’t recognize this they are going to be in deep trouble. The second, more mundane, point is that because Christians have, at times, been subject to persecution by the Zoroastrian authorities, the emperor is now alert to the welfare of a particular class of Persian subject in a way no Roman emperor had ever been before. Constantine’s concern for Christians beyond the empire and his conviction that he has the very best God on his side are both consonant with his views expressed elsewhere, and it was most likely only pressing need on other fronts that kept him from taking action earlier.

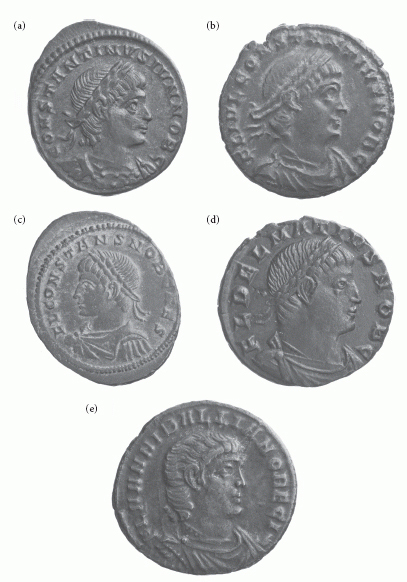

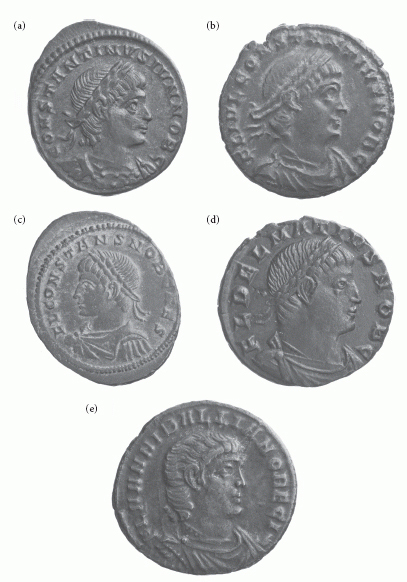

FIGURE 32.1

Constantine’s vision for the future. The Caesars of 335 AD: Constantine II (a), Constantius II (b), Constans (c), Dalmatius (d), and Hannibalianus (e). Source: Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

War with Persia was important for the succession plans that Constantine had come to envision in 335. His praetorian prefects’ long careers show him rewarding loyalty with loyalty. His half-brother, Dalmatius, who had shown loyalty to Constantine as well as considerable ability, had spent most of the reign in Toulouse before being promoted to the consulship in 332, then to a senior command on the eastern frontier. In 334 he had crushed a revolt on coastal Cilicia, then on Cyprus. In 335 Constantine named Dalmatius’ two sons, Flavius Julius Dalmatius and Flavius Julius Hannibalianus, as Caesars on a par with his own sons by Fausta (see figure 32.1). After that, the younger Dalmatius appears to have been based in the Balkans while Hannibalianus was married to Constantina, Constantine’s older daughter with whom he appears to have resided in Constantinople.

The appointment by Constantine of his nephew/son-in-law to the title King of Kings and king of the Pontic Peoples was a virtual declaration of war (certainly, it would have been read as a declaration of intent), for the title “King of Kings” was the title of the king of Persia. The story circulating that Constantine had been misled by a lying merchant who told him that treasures entrusted to him for the emperor by an Indian king had been stolen by Sapor may have been invented to conceal the degree of advance planning. Be that as it may, the war that would now ensue would ultimately go nowhere from the Roman perspective and would result in years of bloody conflict, largely on Roman territory.9