CHAPTER 3

HAMIDIAN MASSACRES AND THE MEDIA

“The reports from our Constantinople agent confirm the allegations that the determination of the Ottoman government is to ‘remove’ the Armenians from the Sassoun region and the Committee desires to draw Lord Salisbury's attention to the grave state of affairs caused by the action of the Turkish officials.”

– Edward Atkin, Armenian Relief Fund, August 31, 18951

“Who could have believed it possible that the people of Europe would look on with utter indifference while the Sultan slaughtered 50,000 Christians and reduced 400,000 to the alternative of starvation or Mohammedanism – that even England would do absolutely nothing to restrain him?”

– American Resident in Turkey, January 18962

Reports of massacres in the village of Sassoun reached Britain in the winter of 1894. The Sassoun massacres marked the beginning of a multi-year campaign of government-sanctioned violence directed against Armenians living in eastern Anatolia and in Constantinople (Istanbul). Unfair taxes and security concerns prompted protests that called for the reform of a system that pitted Muslims and Christians against one another. Sultan Abdul Hamid II's (1876–1909) policy of arming irregular regiments of Kurdish fighters to manage the situation had the effect of raising tensions that periodically had erupted into conflict between the inhabitants of multi-ethnic and religious towns. No one anticipated the brutality and extent to which these clashes would culminate in the mid-1890s. By the time the massacres subsided in 1897, sectarian violence had claimed the lives of between 80,000–100,000 Armenians.

The British public and politicians followed the details of the killings in the media over the next four years with a mixture of horror and outrage. Treaty commitments and a growing humanitarian idealism implicated Britain and its Empire in the crimes committed against Armenians. The response to the so-called Hamidian Massacres came in grindingly slow fits and starts. In the end, humanitarian diplomacy faltered when it faced its first major test after the Bulgarian crisis.

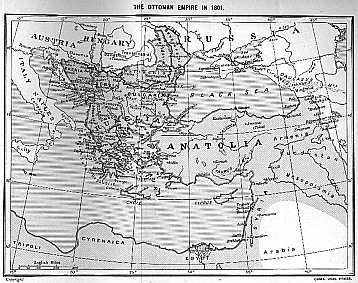

Historians who study the causes of the massacres place the blame on a toxic mix of political and economic rivalries stoked by rumors and paranoia.3 The rise of political consciousness among the Armenian population of Ottoman Turkey, encouraged by a rhetoric of national self-determination and inspired by European nationalist ideals, fueled discontent. Raids on Armenian villages by Kurdish nomads, coupled with high taxes and mismanagement on the part of local government, made life difficult for peasants and merchants living in the six historic Armenian regions in eastern Anatolia (Figure 3.1). There was also the matter of the Sultan who, since coming to power after his brother was deposed by rivals in 1876, worried obsessively over any perceived threats to his authority. He tightened restrictions on Armenian schools and religious institutions while limiting involvement in civic life by closing employment opportunities to non-Muslims.4 His ultimate goal was to strengthen his rule by uniting the majority Muslim population under his leadership. This move alienated non-Muslim minorities, a mix of mostly Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Christian Arabs and Jews. The rise of the Armenian revolutionary political party, the Hunchaks, to protest these restrictions further fed in the Sultan's belief that the Armenian population in particular, mostly peasants, merchants and farmers, were part of an organized resistance movement on the verge of rebellion.

Figure 3.1 Historical map showing the diverse regions of the Ottoman Empire in the early nineteenth century. Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

The Sultan fully embraced closer ties between Islam and the state. He took on the designation of “Caliph” to make his point, even though Sultans before him had long since ceased to use this title. This move clearly identified Turkey not as a multi-ethnic and religious empire, but as a Muslim power and leader of the Muslim world. The loss of territories in Europe along with their sizable, mainly Christian and Jewish populations after the Russo-Turkish War fueled this vision to unify the Ottoman Empire under the banner of Islam. Abdul Hamid's campaigns against Christian minorities stemmed, in part, from paranoia, but also from a fear of the further dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia, a region one official called the “crucible of Ottoman power.”5

The press confirmed rumors of massacres happening in Sassoun and reported on subsequent attacks on the Armenian population in the region. Massacres soon spread to the six villayets under which the Ottoman government had organized the civic and religious life of the Armenians. Violence eventually reached Constantinople after a bold and ill-conceived attempt by Armenian revolutionaries to close down the Imperial Ottoman Bank to draw the attention of the West to the massacres in 1896.6 News of massacres, forced religious conversions, rape and the destruction of public and private property confronted readers of daily newspapers and political reviews. Blame was placed squarely on the shoulders of the Sultan. As one journalist concluded: “I suppose that no man in England of ordinary intelligence any longer doubts the essential truth of the charges made against the Turkish Government in regard to the Sassoun massacres.”7

Reports that large gangs of Kurds attacked and killed 200 Armenians in coordination with the government on the grounds that Armenians had not paid their taxes initially sounded the alarm in Britain in the summer of 1893. Rumors led to unsubstantiated claims that revolutionaries were behind the tax protest and justified the massacres.8 Subsequent reports from British consular officials and other eye-witnesses confirmed the extent of the violence and the identity of those who participated in killing tax protestors. “These atrocities were committed deliberately, in cold blood, after all resistance had ceased, by those who had done but little fighting,” the press reported.9 “The victims were mostly women, children and unarmed men.”10 Armenians were not the only targets. Though they reportedly “suffered more than the other Christians in the empire,” news of the Sultan's crackdown on Christian religious minorities prompted concerns for Assyrians or Nestorians, Greeks and Arabs as well as mixed Catholic and Protestant populations.11

Concerns raised over the massacre of Armenians translated into widening the sphere of British foreign policy obligations. Of the major European powers, Britain had the most dramatic initial response to the massacres. It issued official government reports in the form of Blue Books, reports carried out under the sanction of Parliament. Britain also pushed for investigations by the Sultan and even threatened a show of military force at one point. Press coverage of civilian massacres in the Ottoman Empire represented humanitarian intervention as a duty of the British Empire, a guidepost of the pax Britannica.

Humanitarian and political organizations supported the Armenian cause with fund-raising and journalists and politicians kept the issue in the news by publishing reports and sending correspondents to investigate the massacres. Journalists, in particular, played a central role in linking humanitarian agendas with an activist liberal foreign policy. Victorians who supported the cause of Ottoman minorities were inspired by press coverage of the massacres and what was being done to help. This turned the moral question of whether or not to intervene into a populist form of engagement with foreign and imperial affairs. In an era of mass media and growing liberal idealism, the Armenian massacres prompted public debates over the role of Britain and its empire in the wider world.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II

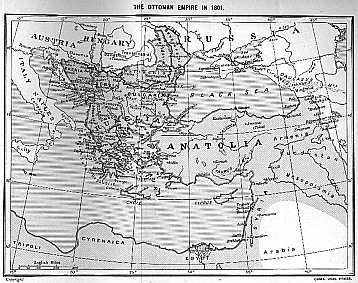

Disparagingly known as “the Great Assassin” in Britain, Abdul Hamid II was the last Sultan of the Ottoman Empire's old regime (Figure 3.2).12 Fascination with the Sultan, his foreign policy and his own personal demons drove public interest in the man blamed for the massacres. He came to the throne in 1876 in the midst of the Bulgarian Atrocities controversy, replacing his brother, who reportedly had gone mad, and reigned until deposed by the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 (further discussed in Chapter 4). The course of his reign thus spanned a tumultuous period of reform and revolution that would culminate in the decline of Ottoman imperial legitimacy. His role as both alleged perpetrator and ultimate defender of the aims in the Armenian massacres sealed his reputation in the minds of Britons as an autocrat who had embarked on a program of extermination to rid himself of troublesome dissenters who challenged his policies.

Figure 3.2 Caricature of Sultan Abdul Hamid II as the “Assassin.” Punch, September 26, 1896.

Abdul Hamid immediately suspended the constitution upon coming to power in the hopes of consolidating his rule. Much to the chagrin of his European allies, he also tried to circumvent reforms to the treatment of Christian minorities dictated by the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. But Britain had helped Turkey thwart Russian ambitions in the region by softening peace terms and thought it could dictate the peace and the enforcement of the treaty. Some concessions already had been made. Protests from the Sultan and British worries over Russian influence in the region resulted in the rejection of the first attempt at peace in the Treaty of San Stefano, which would have granted limited autonomy for the Armenian provinces under Russian supervision. British foreign secretary Lord Salisbury responded by negotiating a watered down version in Article 61 of the Berlin Treaty which, as we have seen, put Britain in the driver's seat in overseeing reforms that increased security in “the provinces inhabited by the Armenians.” Article 61 did not make any promises of autonomy for the Armenian villayets. Despite these changes, the Sultan showed little interest in enforcing the Berlin Treaty. Britain reminded the Sultan of its role in curbing the ambition of his Russian foe in the war first by letter and then, after no response, by sending a British warship to his door.13 The Sultan reluctantly agreed to enforce the Treaty by overseeing reforms. However, when the threat passed and the British departed, these promises were easily forgotten.

In 1895, the government tried this tactic again in hopes of stopping the massacres, but to no real effect. Queen Victoria, in her diary, called “this Armenian business very difficult, as the Sultan behaves so ill about it.”14 Lord Salisbury, now the Prime Minister, responded to the massacres initially with strong rhetoric and promises to enforce the Berlin Treaty. He also threatened the Sultan with military action. Opposition in his cabinet and from the Admiralty put a stop to Salisbury's plans to intervene. Russian concerns over Britain acting unilaterally on behalf of the Armenians also played a role in the decision not to use force. Instead, Salisbury negotiated with the Sultan to organize a commission led by Ottoman officials to investigate the killings.

In December, Queen Victoria recorded her feelings about the matter again, “The shameful, savage massacres of the unfortunate Armenians, men, women, and children, and the misrule in Constantinople is too dreadful. The Ambassadors are at their wit's end.”15 A few days later, Salisbury came to dinner. The Queen recorded that the issue had started to “make him very anxious.” “The trouble with the Armenians continues in every direction, in spite of the Sultan's promises of redress. The massacres continue, and thousands of unfortunate people have not only been killed but been rendered homeless and are threatened with famine. But what is to be done?”16

Considered a sham by critics, the commission found little wrongdoing by Turkish troops and armed Kurdish militias. Blame for the massacres was placed on Armenian revolutionaries who the report accused of inciting violence against the government. Reports from the consuls stationed in these regions contradicted these findings. Consular reports published and read back in Britain provided eyewitness accounts of massacres and, though they did not challenge the Sultan in any official capacity, offered confirmation of earlier accounts. Increased awareness of politically motivated massacres cast British foreign policy as intimately connected with the fate of the Armenians, who represented in the mind of the public and some politicians a just cause.

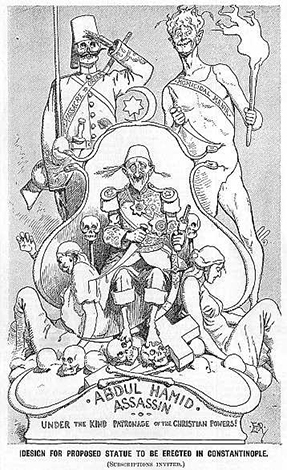

Media coverage raised questions about the extent to which Britain had an obligation to put pressure on the Sultan to stop the violence (Chart 3.1: 1890s media coverage of massacres). Like coverage of atrocities committed around the world today, periodic reports of massacres offered little means of ascertaining when they would end. This uncertainty was expressed as anxiety in the press, which asserted that, in the wake of failed diplomacy, Britain needed to act. The still-unenforced Treaty of Berlin, according to critics, caused the “slavery and oppression” of “millions of miserable Christians to the most abominable tyranny that the world has ever seen.”17 The failure to stop the Armenian massacres made matters worse. The press laid the blame squarely at the feet of Abdul Hamid. As one source put it, “I would not go the length that some have gone in calling Sultan Abdul Hamid ‘an assassin’ or a ‘murderer’ – he may have been an innocent dupe – but certain it is that the system of personal rule, exercised through wicked agents, which was his creation, is responsible for the blood of the Armenians.”18

Chart 3.1 1890s media coverage of the Armenian massacres. Numbers of articles published in the provincial British press (England, Scotland and Wales) on the Armenian massacres, 1894–1901. Gale nineteenth-century British newspapers database. Accessed: November 9, 2014. Series 1–4.

Such clamoring contributed to the Sultan's growing paranoia. Fear that the same fate that met his brother and uncle would befall him – both rumored to have been murdered by the opposition – he walled himself up in his fortified palace, Yildiz Kiosk on the Straits of the Bosphorus in Constantinople. There he found himself subjected to rumors of plots against him by his advisors who wanted to keep the Sultan under their influence and reportedly “rid themselves of the Armenian element.”19 With anger and dismay he had watched the slow dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, starting at the beginning of his reign with the loss of Bulgaria and parts of what was then the westernmost boundary of the empire after the Russo-Turkish War. Reforms to the administration of the Armenian provinces were seen as a further threat to the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. Increasingly, the Sultan came to view the agitation over Armenian reforms as an attempt by the Great Powers, led by its erstwhile ally Britain, to completely destroy the Ottoman Empire.

Pressure from Britain and negative press coverage regarding the Armenian massacres only intensified these fears. But Britain had little interest in taking over the administration of Armenia from Abdul Hamid. The proposed reforms were relatively modest and difficult for a foreign power to enforce. His response to Article 61, according to one former Greek attaché in the Turkish foreign office, bordered on the fanatical. On the eve of the massacres he reported the Sultan as warning that if any foreign power threatened to enforce reforms in Armenia “the waters of the Bosphorus shall be dyed with the blood of all Armenians.”20 The Sultan was represented as a leader who was out of touch with conditions on the ground and therefore could not be trusted in negotiations. “Abdul the Damned” was how the barrister, sometime journalist and longtime resident of Constantinople, Edwin Pears, characterized Abdul Hamid in his biography of the Sultan.

Though some called him a kind man who even was rumored himself to have Armenian ancestry, others considered “the infamous massacre of the Armenians” as “one of his most abominable crimes” which were attributable to a “condition of mad terror in which he was constantly kept by the false reports of spies.” The first Admiral of the Fleet, an admirer of the Sultan, used rumors of the Sultan's supposed Armenian heritage to puzzle over the question of why he “massacred more Armenians than had ever been massacred before.”21 Gossip about the Sultan was in ready supply and continued until he was exiled in 1909. Diplomat and political observer Arminius Vambery's observations found their way into the press. A “very rich” man “with “expensive hobbies,” “he was extremely strict in enforcing obedience to the Koran” and “tyrannical in his dealings with his family and arbitrary in dismissing his ministers.” Considered a “clever diplomatist,” Vambery also believed him to be a “fanatical hater of Great Britain and it was impossible to alter his views or mitigate his rancor.”22

From this perspective, then, the Sultan's handling of the Armenian massacres marked the low point of his reign and further weakened the Ottoman Empire. Pears, writing in 1917, called him simply “the greatest of the destroyers of the Turkish Empire.”23 Upon news of Sultan's demise he was called “the last of the autocratic Sultans of Turkey.”24 Though some maintained the Sultan was “ignorant of these outrages” in the beginning, his refusal to speak out against the Armenian massacres once they started implicated him in the murders. Eventually he would turn on those Muslims who attempted to intervene on behalf of their Armenian neighbors. “Every European resident in Turkey heard stories of Moslems (sic) who had been persecuted because they had sheltered Armenians from the brutal cruelty of their Sovereign.”25 It was his growing distrust of his subjects, erratic behavior, and lack of integrity that condemned the Sultan in the minds of his British critics. “The Sultan first denied the fact of the massacres, then decorated with exceptional éclat the Mufti of Moush” who had been responsible for the Moush village massacres. In turn, this observer continued, he dismissed one commander “who had protested against the massacres.”26

This view of the Sultan and of the massacres committed in his name influenced public opinion not only in Britain but also in the United States, with its growing population of diaspora Armenians. Media coverage sparked a massive fundraising and public awareness campaign over the plight of the Armenians that gave added weight to the British campaign against the massacres.

“This deplorable Armenian business”

News of the killings brought W.E. Gladstone out of retirement again. This assured that the campaign against the Hamidian massacres would go global. His advocacy work on behalf of Armenians left an indelible mark on the response to the tragedy unfolding in the Ottoman Empire. An old man near the very end of his life, he understood this as his last campaign. “In this deplorable Armenian business (for so us all must call it),” he wrote to a colleague, “I have determined from the first to be guided by official and responsible authority and not by any ex parte statement and on this rule I have acted.”

Gladstone kept a keen eye on the Armenian situation well before the Hamidian massacres began. The response he launched to the Bulgarian crisis offered a gateway to the impending Armenian crisis. He was already well-known as a friend to the Armenians, corresponding with Armenian leaders abroad, including Boghos Nubar Pasha in France and the Armenian Patriarch in Constantinople, who in 1880 wrote him a seven-page letter discussing Britain's treaty obligation, Christian populations in Turkey and the Armenian question. In 1891, the London editor of the Armenian paper Haisdan wrote to Gladstone and praised him for his support of the cause of “civilization and humanity” and the Armenian nation.27 Within his own personal and political circles, Gladstone kept in contact with the head of the Anglo-Armenian Association and other known supporters of the Armenian cause, including James Bryce, who would play a key role in bringing the Armenian Genocide to world attention in 1915.28 In 1889, he launched a campaign against Armenian atrocities in what the Daily News labeled “The Turkish Cruelties in Armenia.” Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury responded to the killings as well and ordered a Blue Book published that included correspondence from consular officials and the ambassador about what was called the “condition of the populations in Asiatic Turkey.”29

Gladstone's long-standing disdain for the Sultan colored his view of the Armenian question. He took to calling Abdul Hamid “the Great Assassin,” and refused to mention him by name. On one occasion, he referred to him only as “the assassin who sits on the throne of Turkey.”30 Gladstone's inflammatory changes against the Sultan led to accusations that he was launching a crusade against Muslims. This, critics argued, would undermine the strength of the British Empire as an important Muslim power. Gladstone demurred, strongly asserting in The Times his as “no crusade against” Muslims.31 Wars, he maintained, should be fought for just cause, not religious prejudice. Gladstone had warned against going to war with Russia to maintain the status quo in the Ottoman Empire in an article published in the spring of 1878: “A war undertaken without cause is a war of shame, and not of honour.” Britain, in his view, should instead rely on diplomacy to promote moral and civic reforms which benefited all of the Sultan's subjects: “The security of life, liberty, conscience, and female honor, is the one indispensable condition of reform in all these provinces.”32

Critics charged that this policy substituted one brand of prejudice for another. In “What is the Eastern question”, one commentator rallied against Gladstone's “hypocritical mask of humanity, liberty and religion,” which threatened to expel Muslims from Europe.33 Others worried alongside Disraeli that government by “sentiment” would make a mockery of British power and prestige. To this, liberals responded with appeals to British justice: “It is not a question, be it remembered as is often imagined, of Mohammedan as against Christian; it is a question of the ruling Turk as against all his subjects alike, whether Christian or Mohammedan.”34

If the politics of an unstable regime, rather than religion, had inspired the massacres, the argument went at the time, Britain needed to do what it could to promote the reform of the autocratic Ottoman system. This translated into the by-now familiar call that the love of freedom should inspire foreign policy. Britain's response to the massacres “must be on the side of humanity, freedom and progress, if it is to be in harmony with both her interests and her duty.”35 The political solution he sought was “self-government” not only for the Armenians but for the “Southern Slavs” still living under Ottoman rule.

In this way, the Armenian question was about a foreign policy that supported self-determination for the peoples of southern and Eastern Europe as well as the Near East. Europe had pushed this inevitable process forward with the Treaty of Berlin, which had remade the Balkans. “I am confident,” Gladstone wrote in the summer of 1896, “that those who have been released from the yoke will give their full sympathy to those still under its pressure, and I trust we shall all beseech the Almighty to hasten the day when mankind at large shall no longer have to turn an afflicted eye upon a system in which baseness, barrenness, cruelty, and fraud are so marvelously united as we now see them in the present Sultan of Turkey and his government.”36 Reform would come of its own accord, helped along by Britain's support for the principle of self-determination. Eventually, the desire for independence by subject peoples would cascade across the entire Ottoman Empire.

Gladstone immediately deployed his old friends in the press to make his case. The Daily News carried news of the Bulgarian crisis in 1876 and again during the previous wave of Armenian massacres in 1889. This time, radical journalist Henry William Massingham (1860–1924), who made his name at the liberal-leaning Daily Chronicle, carried Gladstone's campaign forward.37 In a series of letters written to Massingham in the heat of the controversy, Gladstone made his position clear: “So far as my knowledge goes I concur emphatically … and most of all with the concentration of responsibility upon the Sultan.” He concluded by asking him to keep a tight hand “upon the situation.”38 Massingham asked Gladstone to write an article on the topic but Gladstone turned him down, claiming to have “given up all idea of writing on public affairs in my retirement.”39 What he did do was encourage Massingham to use his influence to promote Gladstone's agenda: “this morning upon seeing your letter I began to think there was a glimmering of hope that the country might move on the Armenian question … I am ignorant what is the usage or etiquette as between journals, but if you are inclined to move steady and strongly against the Assassin, would it be possible to get such Unionist papers as the Daily Telegraph, Birmingham Press or Scotsman … to move.”40 He had lost faith in the Tories’ ability to find a political solution but felt like he could pressure their leader, Lord Salisbury. As Gladstone wrote to Massingham, “I should like to see him encouraged in some way to make his position at the very least one of protest.”41

But Gladstone was not long content to work behind the scenes for a political solution. He would speak to the public directly. Though at first he declined “playing Bulgaria over again” he admitted that he would not “refuse to attend” a meeting “if it sprang up there spontaneously.”42 Indeed, he already was preparing a speech on the Armenian question. It would prove his last public appearance before his death. He earned the support of the Prime Minister but had trouble winning over the cabinet.43 In mid-September, Canon Malcolm MacColl (1831–1907), an outspoken supporter of the Armenian cause, wrote to Gladstone's son, Herbert, that he was “overwhelmed with the correspondence on the Armenian question.”44 Later that month, W.E. Gladstone chose Liverpool as the site of protest where he believed his message would have the most impact among his liberal supporters. This speech defined his stance and influenced a generation of Britons when it came to the question of humanitarian intervention. Thousands of cheering supporters gathered in Hengler's Circus in the fall of 1896 to hear Gladstone condemn the previous two years of inaction on the Armenian question.45 The Liverpool message spread. That month witnessed the beginning of a wave of protest meetings that sprung up around the country.

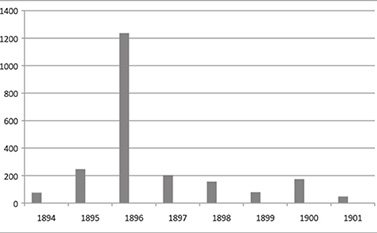

Figure 3.3 1895 map of the Armenian massacres. British Library Map Collection, 48320 (1).

Gladstone never transcribed his speeches and usually worked only from notes. What we know about his speeches mostly comes from the press, which made it a practice to report important political speeches as close to verbatim as possible. Gladstone's handwritten notes, now held in the British Library, from which he presumably delivered the Liverpool speech, reveal why he felt so strongly about this issue and why he traveled from his distant home at Hawarden in Wales to launch the campaign on behalf of Armenians in Liverpool.46 For Gladstone, the section of the speech he labeled “Happy Day” in his notes read that he would “support any effort of HM Gov't to extricate us from our ambiguous position to renounce.”47 He concluded his notes for the speech with the hope that the government would express “our detestation of the most monstrous of all the outrages recorded in the dismal history of modern crime.”48 But the main issue on his mind came towards the beginning of the speech where he sketched the “practical consequences” of Britain's inaction. Below this point he simply underlined the word, “Extermination??”49

The speech inspired Liberals to challenge the Conservative government to act. Lord Salisbury ordered an investigation and saw the publication of the Armenian Blue Books during his time in office. But the Liberals protested loudest and made the issue their own. In short, the Liberal party believed that it could win by backing the Armenian issue just as Gladstone had swept the 1880 election on a wave of moral indignation after Bulgaria. The success of the Midlothian campaigns remained a potent reminder of the power of taking the moral high ground when it came to foreign policy. In a direct attack on Conservative party leadership, Gladstone blatantly accused Salisbury of making a “deplorable error” when he “compromised every point” to the European Great Powers on the Armenian question.50 Others were not as sure. As Queen Victoria recorded one government official saying in her diary, “all these meetings and speeches about Armenians … only makes it more difficult to settle.”51

The response to the Armenian crisis was always also about domestic political rivalries and different visions of Britain and its empire's role in the world. “My dear Gladstone,” wrote James Bryce in the wake of the Liverpool speech, “It was with great pleasure that I saw that you had been delivering yourself on the Armenian question and the deplorable inaction of our Government. What you said about that seemed to me perfectly true and very effectively put: and I wish there were more … Liberal leaders who would speak out in the same sense.”52 Bryce was busy at this time compiling a “massacre map” that indicated the location and extent of the killings (Figure 3.3).

Malcolm MacColl kept a close watch on the campaign, complaining that some in the Liberal party did not support the cause. “It is bad for the Liberal leaders to condone this practical betrayal of Armenians,” he told Herbert Gladstone, confiding that he hoped that W.E. Gladstone's work would help to “oust Rosebery” as leader of the Liberal Party, who had shown little leadership on the Armenian question.53 “Why did he not insist as your father would have done?” he asked Herbert rhetorically.54 The controversy would eventually cost Rosebery the Liberal Party leadership.

In the end, Gladstone's campaign did more to provoke outrage than create sound foreign policy. No political solution emerged to put an end to the massacres which continued long after Gladstone's speech in Liverpool. As the Grand Old Man admitted at the end of his life: “I am now a dead man as to general politics … I am waiting in desire rather than in hope of some mitigation in the Eastern question.” Indeed, the Armenian question would not see resolution in his lifetime. Queen Victoria on her jubilee in 1897 recognized the envoy sent by the Sultan to congratulate her many years on the throne. As Gladstone wrote to Massingham: “the Gov't ought to have conferred to the Sultan their regret that they could not assign to his Envoy any place in the procession.”55 The humanitarian movement, rather than the political establishment, ultimately found inspiration in the campaign that Gladstone had risked the fortunes of the Liberal party in general and the political future of Lord Rosebery specifically. This episode had long-term implications for how Britain, and the international community, would respond to reports of massacre and, eventually, genocide.

The Press and the Armenian Cause

The media-saturated world of Victorian Britain meant that open debate and “free expression” thrived around the Armenian issue. In the midst of the Armenian controversy, the Foreign Office issued a statement from Lord Salisbury declaring that “his Lordship does not wish in any way to interfere with the free expression of public opinion on the [Armenian question].”56 This openness allowed a culture of dissent and debate to thrive. With near universal literacy achieved and the end of the Stamp duties on newspapers in place by the turn of the century, information flowed more rapidly and more widely than ever before. Cheaper raw materials and better printing technologies, coupled with improved communication with the rest of the world, paved the way for a mass circulating press whose reach spanned well beyond Britain's shores.

Journalism, too, was changing with the rise of the professional journalist who reported the news, offered opinions and looked for new ways to grab the attention of readers. Newspapers and other periodicals found their way into the hands of the middle-classes who read, wrote letters to the editor and discussed the latest news. The public, it turned out, had a lot to say about what the government should or should not do to help the Armenians. Around the issue of the Armenian massacres grew up a culture of humanitarian activism supported by the mainstream and advocacy press, pamphlets, parliamentary debates and public meetings.

Journalists who embraced the humanitarian ideal were responsible for putting the Armenian issue most compellingly before the public. Humanitarian journalism emerged as a genre of news reporting that supported particular causes in the press with the intention of influencing public opinion. This activist brand of journalism had its origins in the anti-slavery journals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By the Victorian period, journalists pursued this as a distinct genre and style of reporting the news. While some defended humanitarian journalism as vital to democracy and called it a voice of the people, others claimed that advocacy for particular causes had no place in serious journalism. One journalist blasted the “new humanitarianism,” “Which peals periodically from a part of the London press” for promoting the hypocrisy of selectively defending fashionable humane causes.57 Though partisan journalism long had characterized the Victorian press establishment, this activist brand of media was a relatively new phenomenon.

For critics, humanitarian journalism belonged more to the category of sensationalism embraced by New Journalism. New Journalism, as practiced by the mass circulating dailies of the time, looked for any opportunity to shock readers with dramatic stories in order to get them to buy newspapers. “It may be a noble rage,” wrote the National Observer regarding the Armenian massacres, “but it goes beyond bound and runs into madness.”58 For those who championed humanitarian journalism, however, the press was the heart, soul and most importantly, conscience of liberalism. Humanitarian journalists campaigned to end child labor, vivisection, animal abuse and domestic violence at home. Abroad, in addition to the suffering of minority Ottoman Christians, it was the horrors in the Belgian Congo under the reign of King Leopold II that put humanitarian journalists at the center of highly visible campaigns which they helped form and promote.

The most prominent humanitarian journalist of the Victorian period was muckraker W.T. Stead. Gladstone was drawn to Stead's passionate style and recruited him to promote his campaigns. Similarly, Stead used Gladstone's populist brand of politics around the Bulgarian Atrocities to promote his own career. Bulgaria, according to one source, provided the opportunity to bring “this question into life.”59 Stead, as he later did with campaigns such as child prostitution in England or “White Slavery” as he called it, took on the Armenian question as a mission, elevating the controversy to the level of a political movement.60 As editor of the Northern Echo he built a career as a moralizing journalist. “I am a revivalist preacher and not a journalist by nature,” he once claimed.61 The Bulgarian crisis provided this liberal dissenter with the opportunity to take his campaign against Turkish atrocities in Bulgaria from the pages of the Northern Echo to the public meeting hall. The agitation quickly took hold in the largely Nonconformist north of England where Stead counted 47 protest meetings during the summer of 1876.62 Gladstone so admired Stead's activism that he entrusted him with his papers in the hopes that he would one day write the history of the Bulgarian agitation.63

Stead's populist style of journalism, putting sensational reporting in the service of humanitarianism, carried over to his later work as editor of the Pall Mall Gazette and the Review of Reviews. There he published close to 100 articles on the Armenian question up until he went down with the Titanic in 1912. Stead reflected on the moral imperative that set him writing. Religious piety, combined with a higher sense of public duty, led to his vow “to stimulate all religious men and women, to inspire children and neighbours with a sense of supreme sovereignty of duty and right.” England's leadership as an empire (“keep(ing) the peace of one-sixth the human race,” as he put it) obliged it to take responsibility for righting wrongs in regions where the empire had made diplomatic commitments. In the Armenian case, this translated into upholding international treaty obligations in the Treaty of Berlin.

On the eve of the massacres, Stead approvingly reported that the “the wrongs of the Armenians” had been brought “before the House of Commons and of the British Public by representations in the press.” Stead claimed that the Berlin Treaty made Britain, “peculiarly responsible for the prevention of those atrocities” past and future. He advocated a diplomatic approach, arguing that short of “train(ing) guns on the Sultan's Palace on the Bosphorus … it would be well if Lord Rosebery and the English Press would endeavor to put a little more pressure upon the Grand Turk.”64 Stead took on the role of key informant as soon as the Armenian massacres began in fall 1894: “The news from Armenia is very horrible. The Turks and the Kurds have been at their bloody work again – and this time on a larger scale than usual … By orders from Constantinople Turkish regular troops aided by [Kurds] destroyed twenty-five Armenian villages, slaying from three thousand to four thousand men, women and children, subjecting them … to every extremity of outrage.” He concluded: “The facts seem to be beyond dispute.”65

Gladstone's campaign to bring the Armenian cause to the public relied on men like Stead. In the feature article, “The Storm Cloud in Armenia” Stead wrote, “The recent display of the Ottoman method of dealing with troublesome Christians has naturally aroused Mr Gladstone … It needed, however, the brutal massacre of Armenians at Sassoun to arouse the public to a sense of what Turkish rule actually means to the Christian province.” He gave the Armenian cause legitimacy by connecting it to earlier campaigns that had roused the public: “As in the old days of the Bulgarian horrors, Mr Gladstone took the field in person and launched on the eve of the New Year one of those sweeping anathemas which no one can pronounce with so much authority and vehemence as the great pontiff of political humanitarianism.”66 In the wake of the Young Turk Revolution that brought on another wave of sectarian violence in 1908 (see Chapter 4), Stead published articles arguing that Britain put pressure on the new Ottoman government to reform its minority policy.

Journalist E.J. Dillion (1854–1933) took Stead's brand of humanitarian journalism one step further. While Stead was busy distilling information found in reviews of the day for readers and offering his own editorial comments and directives, Dillon played the role of the investigative journalist. He traveled in disguise to Turkey to see for himself the effects of the massacres and interview alleged perpetrators. A scholar of eastern languages, he clandestinely entered Turkey after the Sultan reportedly explicitly forbade his travel. This resulted in a series of articles on the massacres for the Daily Telegraph and the Contemporary Review which, according to a profile written by Stead about Dillon, “made an immense impression upon the public mind.” Dillon's investigations represented “the most damning description of Turkish government in Armenia that has ever been printed in the English language.”67 Gladstone used Dillon's deposition of a Kurdish leader involved in the massacres to make his case for action in a speech at Chester where he “challenged the Ottoman Government to deny the statements there made.”68 Dillon believed that “the responsibility for the ghastly massacres which have horrified the world in Armenia lie at the door of England,” an accusation Gladstone had once leveled at his own Liberal party.

Humanitarian journalism also took hold in periodicals that targeted women readers. Feminist perspectives on the Armenian question appeared in feature articles, book reviews and biographical sketches of women activists in all of the major women's papers, including the Woman's Herald, Woman's Signal, Women's Penny Paper, Our Sisters and Shafts.69 Assuming the role of Britain's moral conscience, liberal feminists found in the Armenians a just cause. In 1895, Shafts published a letter addressed to Lady Henry Somerset (1851–1912), a key voice in this campaign, from the Armenian women of Constantinople that described a series of massacres in that city. Somerset's response to the letter, signed “Your Suffering Sisters,” concluded with a challenge to English women: “Will English women be deaf to the voices that call to them in the hour of their supreme agony? Will they not rise to demand that such steps be taken at all hazards as will secure the rescue of this tortured people?”70

Others echoed Somerset's belief that women should get involved in the Armenian campaign. “We should be callous indeed, if our sympathy remained unmoved by the fearful crimes in the Turkish dominions” wrote one correspondent in Shafts.71 Our Sisters published reports of the massacres in another Armenian town and described the mass murder of “the defenseless crowd of men, women and children” gathered in a church that was then set on fire.

Somerset's own paper, the Woman's Signal, paid particular attention to the Armenian question. Somerset was a liberal committed to the Gladstonian line on the Armenian question. Gladstone's 85th birthday celebration provided Somerset with an opportunity to make the case for “A Call to Action” in the face of the government's inaction in her newspaper columns. In an address at the annual meeting of the British Women's Temperance Association, she argued: “The Turkish Empire has been kept alive by treaties which have been broken again and again … we as a country are powerless to move and are obliged to acknowledge that we are impotent to save the people we agreed to defend.”72 British women, she maintained, should lead the charge and put pressure on Liberals to intervene to stop the massacres. Somerset published articles about “the persecuted Armenian” and appealed to readers to heed “the bitter cry of Armenia.” News briefs reported details of “attacks on Armenians in the very heart of the Turkish government's rule.”73

The Woman's Signal also featured testimony from massacre victims themselves. Somerset retold the story of the killing of one Armenian woman's three-month-old baby and two relatives by Turkish soldiers. The young woman, who escaped to England, was saved by remarkable circumstance: “‘Don't kill this woman,’ said one of the brutal Turks. ‘She is young and pretty; I will take her along with me.’ But she struggled with her brutal captors with all her strength. ‘If you are such a fool,’ said the Turk, ‘as not to go with me quietly, we shall kill you at once.’ She still struggled. They tore her clothes off her back. Her fate was near, the worst of outrages and death at the hands of the men who had just killed her baby before her eyes.”74 When coins that her husband had fastened to her belt fell along the ground, she escaped to the woods while the soldiers picked up the gold and quarreled over the money.

Somerset's dramatic retelling of the story in the Signal echoed Stead in style and substance. Outrages of rape, violence and greed figured prominently in Somerset's version of one woman's ordeal. Taking on the voice of the victim, Somerset issued a call to action: “The Christian womanhood of England as presented by the Woman's Signal can be depended on to demand that the extermination of these people shall be stopped.”75 Moral responsibility for Armenia also meant speaking out against sexual violence and protecting womanly virtue. Somerset's moral outrage was strengthened by her status as a woman. She held a unique position of authority when she described the fate of the woman refugee and represented to her audience an authentic voice of feminine sympathy. This most certainly added moral weight to her campaign while raising awareness of the Armenian crisis among her mostly women readers.76

Humanitarian journalism necessarily facilitated aid work. In 1896, Somerset launched the Armenian Rescue Fund. Donations ranged from the large to the very small and drew in readers from all social classes. Prayer meetings, British Women's Temperance Union Branches, Congregational church members, individuals and anonymous donors including “An English Sister” contributed to the fund, whose purpose was “not only to cover and feed these suffering ones, but to see that they have homes and work.” Donors were assured of the worthiness of the 600 refugees helped by the fund: “Let it be remembered that they do not drink, that they are devout and earnest, exceedingly docile and kind and remarkably quick-minded.”77

Despite such industrious credentials, Somerset assured readers that refugees would be resettled in Marseilles rather than London. The fund also served destitute Armenians still living in Turkey. Somerset reported that by the end of her campaign, the fund raised enough money to support a three-year program to educate and feed a significant number of Armenian orphans. To readers of the Signal she offered her thanks. The money collected from readers served as “eloquent proof of the worth of [the Signal] which has gathered round it the best hearts of the womanhood of England.”78

The media played an important role in disseminating information and raising money during the Armenian crisis. Journalists like Stead, Dillon and Somerset also used the press to advocate for a Gladstonian liberal foreign policy and promote humanitarian ideals. Mass literacy and the popularity of the news media as a source to convey information in a trusted, periodic format made journalists an important part of a culture of politics that defended the rights of others in the name of the pax Britannica. However, journalists like Stead had little difficulty turning the tables on the British Empire. His demands that Britain defend Ottoman minorities came not long before he critiqued British concentration camps for Boer women and children in the Boer War (1899–1902). For liberals like himself, there was a right and wrong way to maintain empire. In the end, humanitarian journalism helped make the Armenian campaigns into a movement that advocated a stronger and more prominent moral leadership role for the British Empire in the wider world.

Knowledge is Power?

Stories of the Armenian massacres bombarded Britons from every direction. The public had access to the information published not only in the press but also in public documents thanks in part to a pamphlet campaign by Armenian advocacy organizations. Through the press, pamphlets and parliament, a narrative of human suffering on a mass scale found its way into Victorian life. This “humanitarian narrative,” as Thomas Laqueur has called it, produced a private and public response to the Armenian massacres that asked Britons to act on behalf of distant strangers. For any humanitarian narrative to have power, according to Laqueur, it must link “sentiment, obligation and action.” “Sad and sentimental” stories about human suffering fall flat if they do not elicit an emotive response that invests the audience in the plight of the victim. Severing this link often results in what we today call humanitarian fatigue.

Stories about the Armenian massacres applied a human face to the unimaginable by logically ordering human suffering and making its immediacy felt. Meanwhile, the repetition of the information found in these reports about the massacres created a pattern of intent that implicated the Ottoman government in a policy that sought the elimination, or in the words of Gladstone, “extermination,” of the Armenian population. As Stead, Dillon and Somerset so well understood, stories of human suffering had their greatest effect when they came from the experiences of individual victims of systematic violence. Thus, collected personal stories from the site of the massacres took on added weight as the tragedy of an entire people. The mass of evidence collected and disseminated to the public during the course of the Hamidian massacres necessarily informed how Britons responded to the killings of distant Armenian strangers.

Between 1889 and 1896 there were ten different Blue Books published on the condition of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. These official volumes contained thousands of pages of information.79 Presented first to parliament and then later disseminated to the public by the media, the reports chronicled evidence of massacres. Information largely came from the eyewitness reports of British consuls stationed in regions where the massacres took place and were accompanied by statements from the British Ambassador to Constantinople who reported meetings with the Sultan and his functionaries to the Foreign Office. These reports also included statements by Ottoman officials that Armenian intrigue was to blame for the massacres. Regardless of how fully or adequately the Blue Books represented what happened, the media relied on information found in these reports in order to convey some sense of what was happening on the ground. Like reports today of atrocities happening in far off places, the public wanted to know something about high profile news items even if they could not know everything. The press along with the Blue Books provided an entry into the world of the massacres that then opened the question of how, or even if, Britain should intervene.

Many of the hundreds of articles published on the Armenian question in the 1890s relied on these official government documents to support particular claims. This included critiques of the diplomatic dealings with the Sultan reported in the Blue Books. “It is impossible for an Englishman to read these dispatches, and to note the offhand, fearless, nay reckless, way in which the Turkish bull was taken by the horns,” commented E.J. Dillon in the Fortnightly Review upon reading about how the British Ambassador dealt with the massacres in a Blue Book in 1896.80 Other journalists used the information from the Blue Books to convey the extent and progress of the massacres. “The reports which come from the interior show that the Government is now trying to restore order and put an end to the massacres. An outbreak at Adana ten days ago was put down with little loss of life, but it is much easier to destroy the peace of a community than to restore it,” commented a writer in the Speaker in March, 1896.81 Still others claimed the Blue Books showed the willingness of the British to intervene and stop the massacres: “We know from the dispatches published in the official Blue-books that the Prime Minister of England was prepared after the first massacres of Armenians in Asia Minor to have put a stop, if necessary by force, to any recurrence of these horrors.”82

Such commentary did little to stop the bloodshed. However, as evidence mounted that the slaughter was planned and perpetrated by the Ottoman government, it drew the public further into the controversy. In the article, “The Red Book,” one journalist commented about the recently published Blue Book, “If symbolism were observed at the Foreign Office, the latest of its official publications would be coloured, not Blue, but red. A more ghastly record than ‘Turkey No. 2, 1896,’ had never been compiled. It puts an end, once for all, to the miserable pretext of the Sultan's organs in this country that the Armenian massacres were magnified into unnatural importance by the heated imagination of special correspondents.” Investigative journalists also offered correctives to the Blue Books which some accused of stemming from sham investigations: “The able and competent men who have furnished the leading journals of the morning press with trustworthy narratives of crimes and horrors unsurpassed in history have turned out to be far better guides than a Commission hampered at every step of is proceedings by Turkish obstinacy and fraud.”83

Thus, information about what was happening in Turkey came to the British public in fits and starts and through an amalgam of sources, both official and unofficial. Others used the Blue Books to show that the massacres were the result of Armenian intrigue and not the Sultan's government. Quotations from Ottoman officials denying the massacres were privileged in these accounts over reports of atrocities committed against Armenian men, women and children. This inspired a back and forth in the media over what to believe in the Blue Books and often spawned heated exchanges. But news of massacres kept coming throughout 1894, 1895 and 1896. The multiple Blue Books published on the massacres ultimately kept the issue in the news while implicating Britain in the solution to the crisis.

A series of pamphlets published by the Information (Armenia) Bureau in London, and directed by Canon H. Scott Holland, did the work of excerpting the Blue Books and other eyewitness testimony for the public. One of the most effective ways of presenting the case for intervention was by using the words of British diplomats and officials on the ground to convey the extent of the horrors. “The plundering and massacre began on Saturday afternoon,” began a report from the Acting-Consul at Angora, “I watched the progress of things from the roof of my house which is situated in the very heart of the city and I report nothing as fact which I do not know from actual observation … Immense quantities of plunder were carried off by Turkish women as well as by the men and boys … Women were most horribly mutilated. The universal procedure seems to have been to insist on their becoming Moslems (sic). If they refused, there were cut down mercilessly – fairly hacked to death with knives, sickles or anything which came handy.”84 This report was excerpted by the Information Bureau and sold as an inexpensive pamphlet.

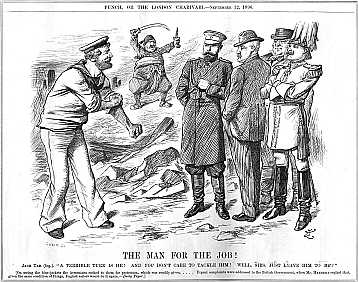

Figure 3.4 “The Man for the Job.” Punch, September 12, 1896.

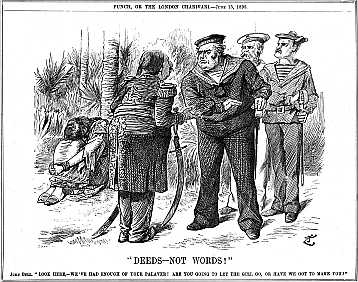

Figure 3.5 “Deeds not Words.” Punch, June 15, 1895.

Evidence suggests that reports of massacres weighed on the public conscience. Activists and humanitarian organizations began to demand a response, as evidenced in the steady stream of letters to the editor in the periodical press and the increasing number of public meetings held throughout the country. In one week at the end of September 1896, The Times reported on the outcome of 21 meetings held in major cities and provincial towns.85 Journalists encouraged this sense of engagement. “The time has come for every reasoning inhabitant of these islands deliberately to accept or repudiate his share of the joint indirect responsibility of the British nation for the series of the hugest and foulest crimes that have ever stained the pages of human history,” E.J. Dillion chastened the public in the Contemporary Review.86 Other commentators wrote of “broken promises” to the Armenians.87

It was up to Britain, then, to find a solution. “The Year of Shame” made the argument for military intervention: “War is, indeed, a great and terrible evil; but it is not the greatest of all evils. Dishonour and infamy are worse than war. Yet there are some who, apparently, would rather take the devious paths of infamy and dishonour than incur even the shadow of a risk of war. It was not thus that the freedom and greatness of England were won in times past.” This dishonorable course, according to the writer, went against Britain's interests: “It is not by putting our conscience into commission, it is not by playing second fiddle in an inharmonious and futile Concert that we shall uphold the national dignity, or safeguard the interests of our great Empire.”88

Had the time come for Britain to take justice into its own hands? A pair of images in Punch magazine showed Britannia flexing its muscles in defense of Armenia. In one image, an English sailor is labeled “The Man for the Job.” With the Sultan in the background he confronts the Concert of Europe with the challenge, “You don't care to tackle him! Well, Sirs, just leave him to me!” (Figure 3.4). In the other image, John Bull is dressed as a sailor who leads the heads of Europe in confronting the Sultan. He defends Armenia, pictured as an abject woman in the background, with the threat, “Are you going to let the girl go, or have we got to make you?” (Figure 3.5).

Diplomats and consuls began to feel the pressure. Ambassador Sir Philip Currie at first refused to make his diplomatic corps into aid workers. When asked to distribute £100 in donations from Daily Telegraph subscribers in early June 1895, he balked: “I do not think it advisable that Consular Officer[s] should undertake distribution of relief … we have no one we could spare for the purpose.” He suggested instead an American doctor.89 Later that month, pressure from the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs led him to consent to act as an agent for the distribution of £1,000 raised by “three leading British merchants” for Armenian Relief through British consuls in the devastated villages of Van and Moush.90

By July, Currie had completely changed his tune. His office now administered money from the London-based Armenian Relief Fund “forwarded through the Foreign Office” by Lord Salisbury for the purchase of food and provisions for victims at Sassoun.91 This work earned him praise in the press: “Thanks to the active sympathy and support of Sir Philip Currie, the relief work is going on undisturbed.”92 The presence of Currie and the other consuls facilitated aid distribution through missionary and humanitarian aid organizations in uncertain times. When the Sultan withheld permission for the American Red Cross to provide aid to villages in the interior, Currie and his agents were the only ones with access to needy populations. In this way, the British diplomatic corps continued the tradition started by Ambassador Layard and British consuls, Captain William Everett, Major Emilius Clayton and Major Henry Trotter in the wake of the Bulgarian crisis. It was through these outlets that aid money collected in Britain and the US traveled and was distributed. Humanitarian aid work thus relieved the public conscience while seeming to make good use of imperial officials abroad.

The response to the massacres, meanwhile, caused chaos in government at home. Activists launched an attack against the Liberal Rosebery and the successor Conservative Salisbury governments in an attempt to force them to act. Memories of the unwillingness of the British government to intervene in Bulgaria led critics to ask for concrete action. Citing the failure of minority protections provisions in the treaties of Paris and Berlin, one writer in the Fortnightly Review asserted that Britain was being misled again by the Sultan: “The whole of Europe has been outwitted, defied, humiliated, and held at bay by a Prince whose throne is tottering under him.”93

Under Gladstone's urging Rosebery came up with a sympathetic though largely ineffectual policy that did little to help either Armenians or Liberal fortunes in the next election. “In spite of the circumstance that the late Liberal Government was in possession of these and analogous facts,” argued one commentator regarding the massacres, the government “found it impossible to have them remedied and unadvisable to have them published.” Hope for resolution would rest with the newly returned Conservative government: “There is fortunately good reason to believe that Lord Salisbury … will find efficacious means of putting a sudden and a speedy end to the Armenian Pandemonium.”94

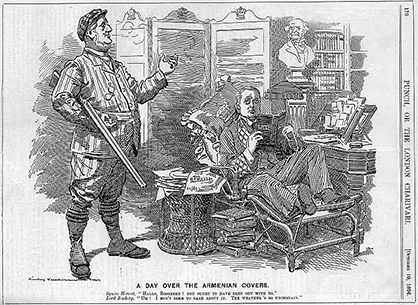

Figure 3.6 “A Day Over the Armenian Covers.” Punch, October 10, 1896.

But the official response remained ineffective. “Public opinion in England has spoken loudly and decisively on the Armenian question,” asserted H.F.B. Lynch in the concluding article of his series on Armenia in the Contemporary Review, “two ministries have taken energetic action, yet, for some reason which has not yet been sufficiently explained, their intervention remains without result.”95 The spirit of reform that first animated debates about British responsibility after the Treaty of Berlin began to gain ground in both Conservative and Liberal Party circles. Salisbury, during his time as one of Disraeli's ministers in 1878, had argued forcefully in favor of a pro-Ottoman policy against Russia. But when Salisbury led the Conservative party to power in 1895, he openly backed a plan for self-government for Armenians that met with widespread public approval. As Lord Sanderson put it, in the wake of the Armenian massacres, “Lord Salisbury declined to pledge the British Government to any material action in support of the Sultan or of the Rule of the Straits, on the grounds of the alteration of circumstances and the change in British public opinion.”96 Salisbury's new-found support for the Armenian cause, designed in part to keep his critics on the defensive, did not amount to any more than the Liberal Rosebery's ineffectual pledges during his short-lived ministry.97

The Armenian crisis proved a heavy burden. Rosebery had not wanted to take over the leadership from Gladstone of the Liberal Party when he finally retired for good in spring 1894. The Liberal ministry under his leadership would last only 15 months. In early October 1896, Rosebery resigned as leader due to “some conflict of opinion with Mr Gladstone” over the Eastern question.98 The ministry was such a disaster that some suggested that in the wake of the Armenian agitation, Gladstone, by now an octogenarian, return to Parliament. Rosebery was satirized as a man hiding from his obligations over the Armenian question while an elevated bust of a disapproving Gladstone looked over his shoulder (Figure 3.6). Rosebery set up a “mock Commission” in the view of his critics that relied on the findings of a Turkish Commission appointed by the Sultan to investigate the massacres which gave “carte blanche to the Great Assassin.”99 The Armenian crisis left the Liberal party “cleft in twain.”

Private Intervention, Public Cause

From a diplomatic and domestic politics standpoint, the response to massacre was a failure. But for some, moral outrage translated into action. Aid programs which targeted persecuted Christian minorities grew in the wake of the Bulgarian Atrocities agitation. Extended coverage of the Armenian massacres reenergized humanitarian relief work among this community. Quaker activist Ann Mary Burgess’ Friend's Mission in Constantinople was characteristic of turn-of-the century relief projects. Part of a larger movement by Quakers to spread their ideals to the far reaches of the globe, the Mission started in the late 1880s and played a key role ameliorating the condition of victims of the Hamidian massacres.

Friends in Britain funded “this body and soul saving work” which also enjoyed the widespread support of other religious and secular aid organizations.100 The massacres started out targeting the male population, which led to the mission's focus on widows and orphans. Burgess, along with two other English women, “stayed at the mission and undertook relief work among the suffering women and children, as bread-winners had become very scarce” after ethnic Armenian relief workers were forced to flee Constantinople.101 As one supporter observed, Burgess saw relief work as a way to “strengthen and revivify the spiritual life of the Armenian Church” not convert her subjects to the Quaker faith.102 To achieve this goal, her mission supported education projects and campaigns for political and administrative reform for minority communities.

Burgess cultivated ties with secular philanthropic organizations and government institutions. The London-based branch of the International Organization of the Friends of Armenia set up operations in eastern Anatolia in 1897. Started to assist massacre victims, it had its own network of patrons whom Burgess used to support her work in Constantinople. Women made up 12 of the 15 members of the Executive Committee; they also held the majority of the 45 positions on the General Committee. The organization was headed by Lady Frederick Cavendish, whose husband, Lord Frederick, was a Liberal MP and a close associate of W.E. Gladstone. Contributions and organizational support came from the Quaker Cadbury sisters, Lady Henry Somerset and a host of titled ladies. Twenty-seven branches of the British Women's Temperance Association also donated to the general fund.103

These women made humanitarian aid work their business. Burgess cooperated with other philanthropists and aid organizations to publicize and raise much needed capital for her projects for Armenian widows and orphans.104 As conditions surrounding the massacres worsened for the Armenian community, relief work took on a more urgent role in and around Constantinople. Quaker W.C. Braithwaite described how Burgess’ Mission bridged the roles of political advocate and spiritual guide, helping “prisoners in obtaining their release, in visiting and caring for the sick, in clothing the naked and in feeding the starving ones around us.” As Braithwaite concluded, “It has been our blessed privilege, also as of old, to see that the poor have the gospel preached unto them.”105 Evangelicalism in this way served a larger humanitarian purpose. This also worked in the reverse. Secular organizations like the Friends of Armenia had little trouble supporting the attempt to revive the Eastern Orthodox Church as they recognized the important role that religious organizations, both Protestant and Orthodox, played in providing aid to massacre victims and maintaining community ties.106 Rather than understand conversion itself as the goal, Burgess put evangelical activism in the service of humanitarian relief and political advocacy.

The Armenian massacres made Burgess anxious to find a way to protect and offer long-term financial support for the primarily women and children survivors. “In the first weeks that followed this political out-burst of hate and fury, we could do little else besides giving out bread to women and children and listening to tales of woe,” she recalled. She immediately began seeking a way to help women earn a living doing needlework, knitting and making “oriental embroidery” that Burgess sold on the local and European market.107 This so-called “industrial work” generated funds through the production and sale of artisan crafts made by needy Armenians. Burgess also used her connections with the consular staff at Constantinople, attending embassy dinners in dresses made with material sent to her by supporters in England who recognized the value of cultivating political connections.108 Burgess' network of philanthropists, businessmen, government consuls, and workers created a thriving industry that supported over 700 women workers and generated sales between 8,000–10,000 pounds a year.109 The British Consul in Constantinople helped defray start-up costs at the mission and supported it throughout its nearly three decades of existence.110

After the massacres, Burgess completely transformed the buildings of what had started as a medical mission into a multifunction campus. She had a meeting hall, schoolrooms and workrooms built alongside living quarters and offices.111 In the midst of extreme uncertainty and social instability, Burgess’ workshops were a place where political rhetoric about the strategic importance of aid met humanitarian action.

Conclusion

The diplomatic and humanitarian response to the Hamidian massacres represented two sides of the same coin. A game of tug of war for the sympathy of the public took place in the pages of the periodical press. Meanwhile, Gladstone's peoples’ foreign policy remained stuck in limbo in parliament. The only tangible action that seemed possible and sustainable during the years leading up to and following the Hamidian massacres was charitable giving which sustained the work of philanthropists like Burgess. Her experiences in the wake of the massacres in Constantinople prepared the mission, in part, to deal with the eventual crisis of world war which brought new diplomatic questions and burdens for humanitarian aid workers like Burgess. A year and a half after the guns of August sounded in 1914, the Armenian Genocide brought home the realities of a conflict that made civilians into war's most vulnerable victims.

But all did not remain quiet during the period between the Hamidian massacres and World War I. In the spring of 1909, a new set of massacres, this time centered in and around the prosperous southeastern Anatolian town of Adana, shook the Ottoman Armenian community. How Britain responded to the Adana crisis in the context of previous massacres foreshadowed the role that it would play in mitigating the effects of genocide in the midst of world war.