Chapter 8

You Get to Choose Where You Work

Some of you will look at your completed flower diagram and have an instant flash of recognition. Oh, now I see what I most want to do with my life.

Others will need a logical series of steps to find that out. For this, you will need two things: Curiosity (yours). And people. People know what no book knows. You must talk to them. (This is called informational interviewing.)

Here are five steps that job-hunters or career-changers have found tremendously helpful.

1. Look at your completed Flower Diagram, and from the center of the Flower choose the top three of your favorite Knowledges (or fields of interest, favorite fields, or fields of fascination—whatever you want to call them). All nouns. On one piece of blank paper, say 8½ × 11, or on your mobile device, copy these in the top half of that page, in their order of importance to you (most important at the top). Beneath them all, midway down the page, draw a line, straight across.

2. Then, look at the Skills petal on your completed Flower Diagram and choose your top five favorite Transferable Skills. All verbs. Copy them down, in order, below the line.

3. Now, take this page and show it to at least five friends, family members, or professionals whom you know. Ask them what jobs or work this page suggests to them. Tell them you just want them to take some wild guesses, combining as many of the eight factors on that page, as possible. Plan B: If they absolutely draw a blank, tell them interests or special knowledges (in the top half of the page) usually point toward a career field, while transferable skills (in the bottom half) usually point toward a job-title or job-level, in that field. So, ask them, in the case of your favorite special knowledges, “What career fields do these suggest to you?” And in the case of your transferable skills, “What job-title or jobs do these skills suggest to you?” If possible, you or they must combine two or three of your knowledges (fields) into one specialty: that’s what can make you unique, with very little competition from others.

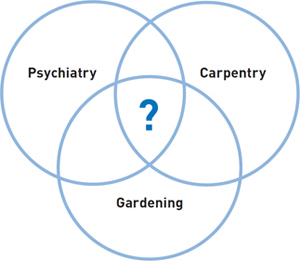

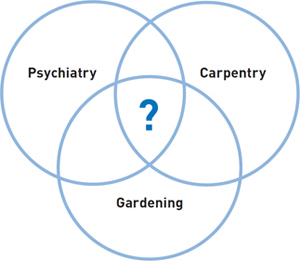

Here is how to go about doing that: let us say your three favorite knowledges are gardening and carpentry and a limited knowledge of psychiatry. What you want to do is use all three expertises, not just one of them—if you possibly can. So, put those three favorite knowledges on a series of overlapping circles, as seen above. Now, to figure out how to combine these three, imagine that each circle is a person; that is, in this case, Psychiatrist, Carpenter, and Gardener. You ask yourself which person took the longest to get trained in their specialty. The answer, here, is the psychiatrist. The reason you ask yourself this question, is that the person with the longest training is most likely to have the broadest overview of things. So, you go to see a psychiatrist, either at a private clinic or at a university or hospital. You ask for fifteen minutes of his or her time, and pay them if necessary. Then you ask the psychiatrist if he or she knows how to combine psychiatry with one—just one, initially—of your other two favorite knowledges. Let’s say you choose gardening, here. “Doctor, do you know anyone who combines a knowledge of psychiatry with a knowledge of gardening or plants?” Since I’m talking about a true story here, I can tell you what the psychiatrist said: “Yes, in working with catatonic patients, we often give them a plant to take care of, so they know there is something that is depending on them for its future, and its survival.” “And how would I also employ a knowledge of carpentry?” “Well, in building the planters, that’s a start, isn’t it?” This is the way you learn how to combine your three favorite knowledges, all at once, no matter what those three may be.

4. Jot down everything these people suggest to you, on your computer, iPad, smartphone, or small pad of paper. Whether you like their suggestions, or not. This is just brainstorming, for the moment.

5. After you have done this for a week or so, with everyone you meet, sit down and look at all these notes. Anything helpful or valuable here? If you see some useful suggestions, circle them and determine to explore them. If nothing looks interesting, go talk to five more of your friends, acquaintances, or people you know in the business world or nonprofit sector. Repeat, as necessary.

6. As you ponder any suggestions that look worth exploring, consider the fact we saw in chapter 7, that all jobs can be described as working primarily with people or working primarily with information/data or working primarily with things. Most jobs involve all three, but which is your primary preference? It is often your favorite skill that will give you the clue. If it doesn’t, then go back and look at the whole Transferable Skills petal, on your Flower Diagram. What do you think? Are your favorite skills weighted more toward working with people, or toward working with information/data, or toward working with things?

7. Just remember what you are trying to do here: find some names for your Flower. Typically, if you show it to enough family, friends or colleagues, you will end up with about forty suggestions.

Don’t ever think to yourself: “Well, I see what it is that I would die to be able to do, but I know there is no job in the world like that.” Dear friend, you don’t know any such thing. Now I grant you that after you have completed it, you may not be able to find all that you want—down to the last detail. But you’d be surprised at how much of your dream you may be able to find. Sometimes it will be found in stages. One retired man I know, who had been a senior executive with a publishing company, found himself bored to death in retirement, after he turned sixty-five. He decided he didn’t care what field he worked in, at that point, so he contacted his favorite business acquaintance, who told him apologetically, “Times are tough. We just don’t have anything open that matches or requires your abilities; right now all we need is someone in our mail room.” The sixty-five-year-old executive said, “I’ll take that job!” He did, and over the ensuing years steadily advanced once again, to just the job he wanted: as a senior executive in that organization, where he utilized all his prized skills, for a number of years. Finally, he retired for the second time, at the age of eighty-five.

Always keep in mind your dream. Get as close to it as you can. Then be patient. You never know what doors will open up.

Maybe you end up looking for the same kind of work you’ve previously done; you’ve decided it gives you all that you love. And you know that industry or field, and you know it well. Okay, then you can skip this step.

But suppose you decide to go for a career change. You’ve identified one, or ones, that sound attractive. But before you go and get all the training or education it requires, or before you go job-hunting for that career, please try it on.

You know when you go shopping at a clothing store you try on different suits (or dresses) that you see in their window or on their racks. Why do you try them on? Well, the suits or dresses that look terrific in the window don’t always look so hot when you see them on you. The clothes don’t hang quite right, etc.

It’s the same with careers. Ones that sound terrific in your imagination don’t always look so great when you actually see them up close and personal.

What you want of course is a career that looks terrific—in the window, and on you. So you need to go talk to people who are already doing the kind of job or career that you’re thinking about. The website LinkedIn should be invaluable to you, in locating the names of such people.

Once you find them, if they live nearby ask for nineteen minutes of their time face to face—Starbucks?—and keep to your word, unless during the chat they insist they want to go on talking. Some workers—not all—are desperate to find someone who will actually listen to them; you may come as an answer to their prayers.

Here are some questions that will help when you’re talking with workers who are actually doing the career or job you think you might like to do:

• “How did you get into this work?”

• “What do you like the most about it?”

• “What do you like the least about it?”

• And, “Where else could I find people who do this kind of work?” (You should always ask them for more than one name, here, so that if you run into a dead end at any point, you can easily go visit the other name[s] they suggested.)

If at any point in these informational interviews with workers, it becomes more and more clear to you that this career, occupation, or job you are exploring definitely doesn’t fit you, then the last question (above) gets turned into a different kind of inquiry:

• “Do you have any ideas as to who else I could talk to—about my skills and special knowledges or interests—who might know what other careers use the same skills and knowledge?” If they come up with names, go visit the people they suggest. If they can’t think of anyone, ask them, “If you don’t know of anyone, who do you think might know?”

Sooner or later, as you do this informational interviewing with workers, you’ll find a career that fits you just fine. It uses your favorite skills. It employs your favorite special knowledges or fields of interest. Okay, then you must ask how much training, etc., it takes, to get into that field or career. You ask the same people you have been talking to, previously.

More times than not, you will hear bad news. They will tell you something like: “In order to be hired for this job, you have to have a master’s degree and ten years’ experience at it.”

Is that so? Keep in mind that no matter how many people tell you that such-and-such are the rules about getting into a particular occupation, and there are no exceptions—believe me there are exceptions to almost every rule, except for those few professions that have rigid entrance examinations as, say, medicine or law. Otherwise, somebody has figured out a way around the rules. You want to find out who these people are, and go talk to them, to find out how they did it.

So, in your informational interviewing, you press deeper; you search for exceptions:

“Yes, but do you know of anyone in this field who got into it without that master’s degree, and ten years’ experience?

“And where might I find him or her?

“And if you don’t know of any such person, who do you think might know?”

But in the end, maybe—just maybe—you can’t find any exceptions. It’s not that they aren’t out there; it’s just that you don’t know how to find them. So, what do you do when everyone tells you that such and such a career takes years to prepare for, and you can’t find anyone who took a shortcut? What then?

Good news. Every professional specialty has one or more shadow professions, which require much less training. For example, instead of becoming a doctor, you can go into paramedical work; instead of becoming a lawyer, you can go into paralegal work; instead of becoming a licensed career counselor, you can become a career coach. There is always a way to get close, at least, to what you dream of.

Before you think of individual places where you might like to work, it is helpful to stop and think of all the kinds of places where one might get hired, so you can be sure you’re casting the widest net possible.

Let’s take an example. Suppose in your new career you want to be a teacher. You must then ask yourself: “What kinds of places hire teachers?” You might answer, “Just schools”—and finding that schools in your geographical area have no openings, you might say, “Well, there are no jobs for people in this career.”

But wait a minute! There are countless other kinds of organizations and agencies out there, besides schools, that employ teachers. For example, corporate training and educational departments, workshop sponsors, foundations, private research firms, educational consultants, teachers’ associations, professional and trade societies, military bases, state and local councils on higher education, fire and police training academies, and so on and so forth.

“Kinds of places” also means places with different hiring options, besides full-time, such as:

• places that would employ you part-time (maybe you’ll end up deciding, or having, to hold down two or even three part-time jobs, which together add up to one full-time job);

• places that take temporary workers, on assignment for one project at a time;

• places that take consultants, one project at a time;

• places that operate primarily with volunteers, etc.;

• places that are nonprofit;

• places that are for-profit;

• and, don’t forget, places that you yourself could start up, should you decide to be your own boss (see chapter 11).

During this interviewing for information, you should not only talk to people who can give you a broad overview of the career that you are considering. You should also talk with actual workers, who can tell you in more detail what the tasks are in the kinds of organizations that interest you.

As you interview workers about their jobs or careers, somebody will probably innocently mention, somewhere along the way, actual names of organizations that have such kind of workers—plus what’s good or bad about the place. This is important information for you. Jot it all down. Keep notes religiously!

But you will want to supplement what they have told you, by seeking out other people to whom you can simply say: “I’m interested in this kind of organization, because I want to do this kind of work; do you know of particular places like that, that I might investigate? And if so, where they are located?” Use face-to-face interviews, use LinkedIn, use the Yellow Pages, use search engines, to try to find the answer(s) to that question. Incidentally, you must not care, at this point, if they have known vacancies or not. The only question that should concern you for the moment is whether or not the place looks interesting, or even intriguing to you. (The only caveat is that you will probably want to investigate smaller places—100 or fewer employees—rather than larger; and newer places, rather than older.) But for a successful job-hunt you should choose places based on your interest in them, and not wait for them to open up a vacancy. Vacancies can suddenly open up in a moment, and without warning.

What will you end up with, when this step is done? Well, you’ll likely have either too few names or too many to go investigate. There are ways of dealing with either of these eventualities.

You will want to cut the territory down, to a manageable number of targets.

Let’s take an example. Suppose you discover that the career that interests you the most is welding. You want to be a welder. Well, that’s a beginning. You’ve cut the 23 million U.S. job-markets down to:

In this case, you want to expand the territory. Your salvation here is probably not going to be informational interviewing face-to-face, but print or digital directories. There is, first of all, the Yellow Pages of your local phone book, either in print or online. Look under every heading that is of any interest to you. Also, see if the local chamber of commerce publishes a business directory; often it will list not only small companies but also local divisions of larger companies, with names of department heads; sometimes they will even include the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes, which is useful if you want to search by the code of your chosen field. Thirdly, see if your town or city publishes a business newsletter, directory, or even a Book of Lists on its own. It will, of course, cost you, but it may be worth it. Some metropolitan areas (San Francisco comes to mind) have particularly helpful ones. Forty of them are listed at www.bizjournals.com.

If you are diligent here, you won’t lack for names, believe me—unless it’s a very small town you live in, in which case you’ll just have to cast your net a little wider, to include other towns, villages, or cities that are within commuting distance from you.

At some point you will be happy. You’ve found a career that you would die to do. You’ve interviewed people actually doing that work, and you like it even more. You’ve found names of places that hire people in that career.

Okay, now what? Do you rush right over there? No, you research those places first. This is an absolute must. Remember, companies and organizations love to be loved. You demonstrate you love them when you have taken the trouble to find out all about them, before you walk in. That’s called research.

What is it you should research about places before you approach them for a hiring-interview? Well, first of all, you want to know something about the organization from the inside: what kind of work they do there. Their style of working. Their so-called corporate culture. And what kinds of goals they are trying to achieve, what obstacles or challenges they are running into, and how your skills and knowledges can help them. In the interview you must be prepared to demonstrate that you have something they need. That begins with finding out what they need.

Secondly, you want to find out if you would enjoy working there. You want to take the measure of those organizations. As I mentioned earlier, everybody takes the measure of a workplace, but most job-hunters or career-changers only do it after they are hired there. In the U.S., for example, a survey of the federal/state employment service once found that 57% of those who found a job through that service were not working at that job just thirty days later, and this was because they used the first ten or twenty days on the job to find out they didn’t really like it there at all.

You, by doing this research ahead of time, are choosing a better path by far. Yes, even in tough times, you do want to be picky. Otherwise, you’ll take the job in desperation, thinking, “Oh, I could put up with anything,” and then finding out after you take the job that you were kidding yourself. So you have to quit, and start your job-hunt all over again. By doing this research now, you are saving yourself a lot of grief. So, you need to know, ahead of time, if this place just doesn’t fit. Now, how do you find that out? There are several ways, some face to face, some not:

• Friends and Neighbors. Ask everyone you know, if they know anyone who works at the places that interest you. And, if they do, ask them if they could arrange for you and that person to get together, for lunch, coffee, or tea. At that time, tell them why the place interests you, and indicate you’d like to know more about it. (It helps a lot if your mutual friend is sitting there with the two of you, so the purpose of this little chat won’t be misconstrued.) This is the vastly preferred way to find out about a place. However, obviously you need a couple of additional alternatives up your sleeve, in case you run into a dead end here.

• People at the Organizations in Question, or Similar. LinkedIn has an extensive menu where you can find a company’s name. They will tell you who works there, or used to work there. An e-mail will sometimes produce an interesting contact; but in this increasingly busy busy life, even the best-hearted people may sometimes say they just cannot give you any time, due to overload. If so, respect that.

You can go in person to organizations and ask questions about the place. This is not recommended with large organizations that have security guards and so on. But with small organizations (in this case, 50 employees or fewer) you sometimes can find out a great deal by just showing up. Here, however, I must caution you about several dangers.

First, make sure you’re not asking them questions that are in print somewhere, which you could easily have read for yourself instead of bothering them. This irritates people.

Second, make sure that you approach the gateway people—front desk, receptionists, customer service, etc.—before you ever approach people higher up in that organization.

Third, make sure that you approach subordinates rather than the top person in the place, if the subordinates would know the answer to your questions. Bothering the boss there with some simple questions that someone else could have answered is committing job-hunting suicide.

Fourth, make sure you’re not using this approach simply as a sneaky way to get in to see the boss, and make a pitch for them to hire you. You said this was just information gathering. Don’t lie. Don’t ever lie. They will remember you, but not in the way you want to be remembered.

• What’s on the Internet. Many job-hunters or career-changers think that every organization, company, or nonprofit, has its own website, these days. Not true. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. It often has to do with the size of the place, its access to a good Web designer, its desperation for customers, etc. Easy way to find out: if you have access to the Internet, type the name of the place into your favorite search engine (Google, Bing, or whatever) and see what that turns up. Try more than one search engine. Sometimes one knows things the others don’t.

• What’s in Print. Not books; their time lag is too great. But often the organization has timely stuff—in print, or on its website—about its business, purpose, etc. Also, the CEO or head of the organization may have given talks, and the front desk there may have copies of those talks. In addition, there may be brochures, annual reports, etc., that the organization has put out, about itself. How can you get copies? The person who answers the phone there, if you call, will know the answer, or at least know who to refer you to. Also, if it’s a decent-size organization, public libraries in that town or city may have files on that organization—newspaper clippings, articles, etc. You never know; and it never hurts to ask your friendly neighborhood research librarian.

• Temporary Agencies. Many job-hunters and career-changers have found that a useful way to explore organizations is to go and work at a temporary agency. To find these, put into Google the name of your town or city and (on the same search line) the words “Temp Agencies” or “Employment Agencies.” A directory of 8,000 such agencies, and people’s ratings of some of them, can be found at the website Rate-A-Temp: www.rateatemp.com. Employers turn to such agencies in order to find (a) job-hunters who can work part-time for a limited number of days; and (b) job-hunters who can work full-time for a limited number of days. The advantage to you of temporary work is that if there is an agency that loans out people with your particular skills and expertise, you get a chance to be sent to a number of different employers over a period of several weeks, and see each one from the inside. Maybe the temp agency won’t send you to exactly the place you hoped for, but sometimes you can develop contacts in the place you love, even while you’re temporarily working somewhere else—if both organizations are in the same field. At the very least you’ll pick up experience that you can later cite on your resume.

• Volunteering. If you’re okay financially for a while, but can’t find work, you volunteer to work for nothing, short-term, at a place which has a “cause” or mission that interests you. You can find a directory of places that are known to do this, in what are called “internships” (www.internships.com) or “volunteer opportunities” (listed at www.volunteeringinamerica.gov—see their data infographic about volunteering leading to employment—and www.volunteermatch.org). Also, you can put into your search engine the name of the city or town where you live, together with the phrase “volunteer opportunities,” and see what that turns up. Or you can just walk into an organization or company of your choice, and ask if they would let you volunteer your time, there.

Your goal is, first of all, to find out more about the place.

Secondly, if you’ve been out of work a lengthy period of time, your goal is to feel useful. You’re making your life count for something.

Thirdly, your distant hope is that maybe somewhere down the line they’ll actually want to hire you to stay on, for pay. The odds of that happening in these hard times are pretty remote, so don’t count on it and don’t push it; but sometimes they may ask you to stay. For pay. The success rate of this as a method for finding jobs isn’t terrific. But it does happen.

After anyone has done you a favor, anytime during your job-hunt, you must be sure to send them a thank-you note by the very next day, at the latest. I emphasized this in tips #9 and #16 in chapter 4. It’s just as important here. Such a note should be sent by you to anyone who helps you, or who talks with you. That means friends, people at the organization in question, temporary agency people, secretaries, receptionists, librarians, workers, or whomever.

Ask them, at the time you are face-to-face with them, for their business card (if they have one), or ask them to write out their name and work address, on a piece of paper, for you. You don’t want to misspell their name. It is difficult to figure out how to spell people’s names, these days, simply from the sound of it. What sounds like “Laura” may actually be “Lara.” What sounds like “Smith” may actually be “Smythe,” and so on. Get that name and address, but get it right, please.

And let me reiterate: thank-you notes must be prompt. E-mail the thank-you note that same night, or the very next day at the latest. Follow it with a lovely copy, handwritten or printed, nicely formatted, and sent through the mail. Most employers these days prefer a printed letter to a handwritten one, but if your handwriting is beautiful, then go for it.

Don’t ramble on and on. Your mailed thank-you note can be just two or three sentences. Something like: “I wanted to thank you for talking with me yesterday. It was very helpful to me. I much appreciated your taking the time out of your busy schedule to do this. Best wishes to you,” and then sign it. Of course, if there’s any additional thought you want to add, then add it. And when you’re done, remember to sign it.

Not likely. Nonetheless, an occasional employer may stray across your path during all this Informational Interviewing. And that employer may be so impressed with you, that they want to hire you, on the spot. So, it’s possible that you’d get offered a job while you’re still doing your information gathering. Not very likely, but possible. And if that happens, what should you say?

Well, if you’re desperate, you will probably have to say yes. I remember one wintertime when I was in my thirties, with a family of five, when I had just gone through the knee of my last pair of pants, we were burning pieces of old furniture in our fireplace to stay warm, the legs on our bed had just broken, and we were eating spaghetti until it was coming out our ears. In such a situation, you can’t afford to be picky. You’ve got to put food on the table, and stave off the debt-collectors. Now.

But if you’re not desperate, if you have time to be more careful, then you respond to the job-offer in a way that will buy you some time. You tell them what you’re doing: that the average job-hunter tries to screen a job after they take it. But you are examining careers, fields, industries, jobs, and particular organizations before you decide where you would do your best and most effective work. And you’re sure this employer would do the same, if they were in your shoes. (If they’re not impressed with your thoroughness and professionalism, at this point, than I assure you this is not a place where you want to work.)

Add that your informational interviewing isn’t finished yet, so it would be premature for you to accept their job offer, until you’re sure that this is the place where you could be most effective, and do your best work.

Then, you add: “Of course, I’m tickled pink that you would want me to be working here. And when I’ve finished my personal survey, I’ll be glad to get back to you about this, as my preliminary impression is that this is the kind of place I’d like to work in, and the kind of people I’d like to work for, and the kind of people I’d like to work with.”

In other words, if you’re not desperate yet, you don’t walk immediately through any opened doors, but neither should you allow them to shut.

As I said, this scenario is highly unlikely. You’re networking with workers. But it’s nice to be prepared ahead of time, in your mind, just in case it does ever happen.

When you’ve found a place that interests you and you want to get an interview there, what will save your neck is this kind of person, whom I call “Bridge-People.” They know you; and they know them. They thus bridge the gap between you and a job.

If you’re on LinkedIn or Facebook, or both, there’s a wonderful website to help you find a bridge-person among people you already know. The site is called Jobs with Friends. Go to http://friends.careercloud.com and it will give you complete instructions as to how to use it. It can be a lifesaver. And it’s free.

What about bridge-people outside your circle of acquaintances? Well, you can’t identify a bridge-person until you have a target company or organization in mind. But when that time comes, here’s how you go about identifying bridge-people:

1. Again, the website, LinkedIn, is your best friend here. Each employer you want to pursue should have a Company Profile page. (Unless the company is just too small.) Identify what place you want to approach, and look up its Company Profile page; go there.

2. Start with the company. Ask LinkedIn to tell you the people in your network who work for the company you are targeting. Then sort that list. You can sort it by employees there, who share:

a. A LinkedIn group with You

b. A former employer with You

c. A school with You

d. An industry with You

e. A language with You

f. A specific location with You

3. Then go to your school. On that same Company Profile page, look for your school—if you ever attended vo-tech school, community college, college, university, or grad school, ask LinkedIn to tell you who among your fellow alumni work for the company or organization you are targeting.

4. Then go to the company activity. On that same Company Profile page, ask LinkedIn to tell you new hires (who), departures (who), job-title changes, job postings, number of employees who use LinkedIn, where current employees work, where current employees worked before they worked for this company, where former employees went after they worked for this company, etc. Insightful statistics!

5. As for connecting with the bridge-people whose names you discover, currently LinkedIn requires you to have one of their paid memberships, rather than the free one, to send a note to someone who’s not a direct connection. But if they’re still working at the company, you can phone the company and ask for them. Or you can search for their contact information through a larger search engine (Google their name!).

6. If you come up blank, both on LinkedIn and all the other places you search for names, such as family, friends, Facebook, etc., (no bridge-person can be found who knows you and also knows them) you can advertise on LinkedIn, for such connections. They have “ads by LinkedIn Members” available to you, for modest cost (so far!). You can also browse LinkedIn groups, and join those (ten at the most) that seem most likely to be seen by the kinds of companies you are trying to reach. However, don’t just join them! Post intelligent questions, respond to intelligent “post-ers” that you think make sense. In other words, attain as high visibility there as you can; maybe employers will then come after you.

Once you get an introduction to a place, follow the instructions in chapter 4 of this book. And, good luck!

Do not pray for tasks equal to your powers.

Pray for powers equal to your tasks.

—Phillips Brooks (1835–1893)