Now gird your loins, dear ones, as we approach one of the more delicate subjects of our study. Actually, don’t bother. You’re going to need full access to your loins here.

From a very young age, Queen Victoria sat on one of the most powerful thrones in history, overseeing the largest empire on earth. And she sat on that throne without any money-back-guaranteed leakage protection. Can you imagine having to take on Prime Minister Robert Peel and all his insufferable Tory cronies without super-absorbent confidence?

Have you ever looked at the covers of your mother’s trashy romances and wondered if those women were pushing away their kilted, oily-chested lovers not because of deep rivalry between their equally sexy clans, but because it was her time of the month and she didn’t want his greasy man-breath anywhere near her?

As much as it spoils the romance of history to know that women of old struggled with aching ovaries and slipping fabrics, they did. If it’s any consolation, their “monthlies” spoiled things for them, too. So they said (and wrote) very little about it, dealt with it as best they could, and got on with life.

It was quite revolutionary when, around the mid-1800s, male doctors developed a fascination with menstruation. They began to study the process. Though in most cases the gentleman’s knowledge was so complete, and the woman’s ignorance so apparent, that study and research were moot. In any event, they realized, not a moment too soon, that women had been menstruating incorrectly. Many a man became determined to teach all of womankind to achieve their full menstrual potential.

It’s Natural, But You’re Still Probably Sinning

Women and girls probably did not menstruate as often in the nineteenth century as they do now. For one thing, girls began their periods later in life, in their midteens, as compared with today’s twelve-year-old average. Good girls, that is.

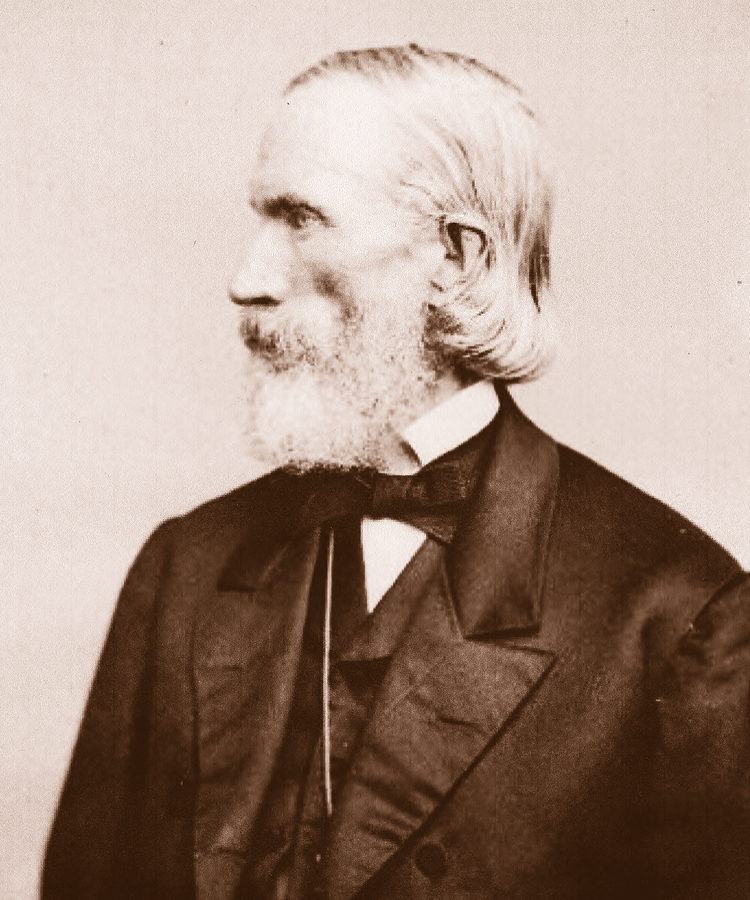

George Napheys, in his 1888 edition of The Physical Life of Woman: Advice to the Maiden, Wife and Mother, warns that a menstruation begun too early is detrimental and that she who develops early fades early, with a “feeble middle life.” And what causes the curse of early menstruation and the overripe sexual disposition that accompanies it? Well, any number of unwholesome indulgences. Attending the theater, having a childhood crush, and, most damaging of all, music.

“Whatever stimulates the emotions leads to an unnaturally early sexual life. Late hours, children’s parties, sensational novels, ‘flashy’ papers, love stories, the drama, the ball-room, talk of beaux, love, and marriage,—that atmosphere of riper years which is so often and so injudiciously thrown around childhood,—all hasten the event which transforms the girl into the woman. A particular emphasis has been laid by some physicians on the power of music to awaken the dormant susceptibilities to passion, and on this account its too general or earnest cultivation by children has been objected to.”

Absolutely. Top hits of 1888 included such lascivious titles as John Philip Sousa’s “Semper Fidelis” march and the painfully overt “Where Did You Get That Hat?” Where, indeed. From the devil’s quivering loins, most likely.

No matter when your “monthly unwellness” came in life, it could still be counted on to visit less often than your twenty-first-century period. Poor nutrition and a harder physical life contributed to scanty menses. And with no standard birth control, a married woman could spend a great deal of her life pregnant or nursing, which stops or at least reduces menstruation. Also, people tended to die more often, and younger, which was also factored into these kind of statistics, though I’m not sure it was fair to do so.

But when it did happen—what did they do?

Whatever Holds…“Water”

I’ll tell you what they did. They did everything. Or they did nothing.

I think.

One of the reasons we know so little about how ladies controlled (or didn’t) their menstrual flow is because no one wrote down the details. The topic appears in literature of the past centuries in one of two forms: the absolutely baffling medical/hygiene treatises we are about to explore, and in the most unsettling of pornography. The world-renowned deviant the Marquis de Sade barely touched on it in his literary tour of sexual hell, The 120 Days of Sodom. Because even a man so depraved that his very name still stands as the definition of sexual torment (sadism) simply could not bring himself to go there.

As for women themselves, few even knew how to write until the latter days of the nineteenth century. And when they did write, they didn’t waste paper and ink on compositions that began: “O my dear Abelard, the cloth I hath fashioned round my womanly fount doth bunch most vexingly.”

Stories beginning “I remember Grandma once saying…” form the bulk of our knowledge, supported by a scattershot of recorded observations.

From various reliable sources, here are the methods of nineteenth-century menstrual hygiene available to you during your stay here:

• Nothing. Clothing was dark. Some experts, including Harry Finley, the curator of the brilliant online Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health, and many of his learned colleagues, believe women simply bled into their clothes, particularly rural women and pioneers. (The nothing method is still practiced in many countries.)

• Sheep’s wool, fluffy side up, after applying lard to the vulvar area to protect against dampness.

• Raw cotton, wadded, secured in cheesecloth, and inserted like a tampon.

• Sea sponges, applied in the same fashion.

• Homemade belts, made out of anything that could be tied around the waist, from leather to string, attached to any reusable pad, forming a T bandage, named for its shape. Most pads, homemade or store-bought, were about the size and texture of a folded hand towel. The pads were run the length of the crotch, belly to back, and safety-pinned (invented in the 1840s), buttoned, or tied to the belt.

• “Clouts”—little cloth triangles with attached strings to tie around a woman’s thighs and waist.

• Crocheted sanitary napkins, attached to a belt.

• No belt or support at all. Ladies with thick enough thighs sometimes just placed towels against themselves, relying on their mighty farm-woman bulk to keep it stationary.

• Baby’s diapers, folded, used with or without a belt.

• Small albino marmoset, clinging tenaciously.

That last one is not real. Probably not. But if my research shows anything, it’s that if you should happen to have had a surplus of mellow marmosets and they got the job done, you would have darned well used marmosets.

That’s not funny.

Hide the Evidence

There are several unnecessarily complicated explanations for how the expression “on the rag” became a common slang for menstruation. One is that women tried to fool the male members of their households into thinking the bloodstained cloths soaking in bleach under the claw-foot tub were leftover rags from the making of jams and jellies, never mind that jam making took place only once or twice a year. This might have been the practice in some homes, but even the most slovenly woman would not have wanted her menstrual blood needlessly on display every time someone came in to use the Necessary. Others talk of “rag bags” where women collected the last tattered remnants of household fabrics, which were then portioned out for flood control. And from a global perspective, rags were at the fancy end of the spectrum; women from non-Western cultures used grass, moss, papyrus, anything that could be counted on to hold an ounce or two. Anything that worked was what women used.

At the end of the century, commercial feminine protection became common, especially since the increasing popularity of mail-order catalogs allowed a woman to purchase it without causing the local pharmacist to suspect her vulgar addiction to menstruation. Reusable and disposable cloths were suddenly available, and waterproof, stain-shielding “sanitary aprons” formed a secure barrier between your clothing and your impudent menstrual blood.

Of course some women chose neither store-bought protection nor any of the simpler homemade solutions. Women who were not afraid to put a little flair into their flow could create garments to rival any of today’s options. A German publication gives instructions on how to origami yourself yet another wonder of Teutonic engineering. See the illustration here.

Toward the end of the century, when cloth was easier to come by, what happened to menstrual rags after they had served their purpose was an interesting indication of wealth and social status. A lady of reasonable wealth could afford to toss her soiled rags, purchased from a catalog for that singular purpose, into the outhouse pit. She wouldn’t even have to let her maids in on that particular vulnerable evidence of her humanity. The maids themselves, however, like most of womankind, still had to wash and reuse their own cloths. The main problem with that being, once these rags were cleaned, they had to be hung up and dried. Where?

Not on the clothesline, that’s for certain, unless your home adjoins an abattoir and you can pass them off as tiny butcher’s aprons (you would never, ever be able to completely bleach a reused sanitary napkin back to whiteness, and there would be no mistaking its true nature). And not over the fireplace either, for these reminders of the curse of Eve were hidden from all members of a household who didn’t use them. Even if you were alone during the day, you couldn’t be sure a neighbor wouldn’t call at your door, watching you through the window as you pinballed around your parlor, hiding menstrual rags like a meth head during a police raid.

Therefore, should you happen to catch a glimpse through a neighbor’s bedroom door of a drying rack set with menstrual cloths, you would know that particular family practiced frugality, either from sense or necessity. And they would know they have the kind of neighbor who peeps in bedrooms. Show some dignity, darling.

“Oh, no! A knock in the darkness! It could be a murderer! He’ll see my jelly rags!!”

Trifling and Tuberculosis

While published advice on controlling the actual menstrual flow was scarce, advice on how to conduct a menstruation cycle was impressively vast and plentiful, and donated to the female gender almost entirely by men. Men wrote books teeming with tips on what a woman should avoid, what her menstrual blood indicated about her health and character, and the many dangers that awaited her if she did not expel her uterine lining with the greatest of care.

Pye Henry Chavasse, who wrote Advice to a Wife on the Management of Her Own Health (1880), was just one of many male doctors with opinions on this subject. He shared the popular belief that certain activities, foods, and drinks could take an already troublesome situation (bleeding from your vagina) and make it lethal. Biggest culprit: cold water. Which was most of the water in the nineteenth century.

“During ‘the monthly periods’, violent exercise is injurious; iced drinks and acid beverages are improper; and bathing in the sea, and bathing the feet in cold water, and cold baths, are dangerous; indeed, at such times as these, no risks should be run, and no experiments should, for one moment, be permitted, otherwise serious consequences will, in all probability, ensue. ‘The monthly periods’ are times not to be trifled with, or woe betide the unfortunate trifler!”

I’m not even sure how one would go about “trifling” with her period. It’s not an activity that lends itself to festive sidetracking. “Oh, gracious, I know I should use a good absorbent napkin and diligent cleansing for this—but the heck with it! This month we’ll see what just cinnamon sticks and doilies can do!”

Hattie’s menstrual-trifling high jinks always got the girls laughing.

According to Chavasse, nearly all cases of hysteria, a disease both powerful and not actually real, can be traced back to uneven menstruation.

Most of these men were not stupid. Their medical educations (if they had them) did enable them to know more than the average woman about the unseen functions of her body, same as today. These men had never menstruated, but that in itself does not disqualify their advice. I don’t demand to see a troublesome mole on my physician’s buttock before allowing him to examine mine.

What does disqualify their advice is that it came mainly from studying incompatible animal biologies, corpses (often of people who’d died from disorders of the organ in question, making their anatomy nontypical), and abashed women seeking help only when they were suffering (again, presenting a nontypical representation).

Probably Chavasse wasn’t thinking about that when he made such declarations as that all menstrual blood, through the entirety of the cycle, “ought to be of a bright red colour, in appearance very much like blood from a recently cut finger.” Any other color or texture, he warned, was a sign of endangered health.

“If [the menstrual blood] be either too pale (and it sometimes is almost colourless), or on the other hand, if it be both dark and thick (it is occasionally as dark, and sometimes nearly as thick, as treacle), there will be but scant hopes of a lady conceiving.”

As most women know, even if your menstrual discharge flows in a rainbow of shades from near black to pink, you’re probably okay. For women to think otherwise could be very frightening for them. Because according to science (“Science.” Oh, that’s fun. Let’s call it that!) many horrible diseases came straight from wrongly colored period blood. Sterility, of course. But also tuberculosis.

“The pale, colourless complexion, helpless, listless, and almost lifeless young ladies, that are so constantly seen in society, usually owe their miserable state of health either to absent, to deficient, or to profuse menstruation.… How many a poor girl might, if this advice had been early followed, have been saved from consumption, and from an untimely grave, and made a useful member of society.”

“Makes Her Most Ugly and Hateful”

The quantity of your menstruation was also important to your general health, as we learn from Orson Squire Fowler, whom we shall revisit many times on our journey, as no other writer can be relied upon for such potent truth bombs as he. Fowler was already an old man when he wrote Private Lectures on Perfect Men, Women and Children, in Happy Families in 1880. He wasn’t remotely a doctor. Well, he was a phrenologist. A word that sounds doctor-y, but many words do. Like “timbrologist,” which is an old word for stamp collecting, a pastime that holds as much medical influence as that of phrenology. But he had a lot of ideas. About everything. From octagonal houses to marital relations to improving farming methods. And of course, like any educated gentleman of the Victorian age he had ideas about women’s periods. His theory regarding menstruation and tuberculosis was slightly more developed than Chavasse’s. Imagine an old man shouting the following information at you:

“Spare menses cause and aggravate all diseases, by leaving surplus albumen [a blood protein, similar to what makes up egg whites] in its victim’s system to create pains and humors. Nature must rid her of it somehow, else she dies, and so burns up in her all she can, which fevers and morbidizes her nerves and feelings, unfits her to bear, and makes her most ugly and hateful, especially to men, and often fairly insane against her husband; besides sending her thick blood tearing through her brain, torrent-like, to gorge, lacerate and soften it… if the lungs are strong enough to help, a part is pressed out from the blood through into their air cells, which she coughs up and raises easily, with difficulty if she has consumption, of which she dies if they cannot do both; so that raising by the gallon proves their strength, and is her salvation.”

Did you get all that? You have been retaining your menstrual protein. Probably because you’re pouting. Stop this foolishness and let the blood come out of your vagina—or it’s going to dice up your brain and choke your lungs. And frankly, with the attitude you’ve been sporting, no one is going to miss you.

Fowler’s solution for sparse menstruation was to lie in bed with all available blankets covering you and apply a towel just taken from boiling water to your abdomen. Then remove the blankets and place a near-frozen towel on yourself instead. Repeat until the blood in your sluggy, disagreeable midsection is galvanized into motion. Also helps with constipation.

“Unclench, woman! Your very life depends on it.”

No Baby Angers Tetchy Uterus

But why must women suffer so? Most nineteenth-century health reformers agreed that although God decreed that woman should have pains in childbirth as penance for original sin, He never actually cursed a woman to suffer during her monthly cycle. Therefore, if your monthlies were unpleasant, it was probably your own fault.

First of all, if your period is not regular, if it is not uniform in shade, and if it does not pass from your uterus as easily and pleasantly as poetry from your lips, the doctor will ask, “Are you married?” Because if you aren’t, it’s obvious that Nature finds you abhorrent and is just trying to let you know.

From Stewart Warren’s The Wife’s Guide and Friend (1900):

“Many of the irregularities of menstruation in single women such as scanty or absent, painful and profuse menstruation… are often cured by marriage, and are in such cases nature’s sign to a woman that she is not leading a natural life.”

Try to imagine your uterus as a highly strung, frantic woman. Which is pretty much how all these writers are imagining it, so you might as well. Anyway, Uterina can’t stand being bored. She wants challenges. She wants work to do. She wants to toss around eggs and play sperm soccer and engorge herself with waterlogged humans four times the size of herself. It’s okay! She’s made for that! She craves it!

Nature’s way: jazzy babies in happy uteri.

And you, who are unnatural, who are perhaps too busy sewing the ridiculous sashes your fellow Sapphics wear while throwing themselves under carriages in a diseased effort to procure suffrage, are foiling her needs. She will see that you pay for that crime: punishment meted out from the very organ you neglected.

Or, bless you, you just might be terribly plain and dull-minded. And no man wants to extend the effort of shoving a ring onto your hoof. In which case I am so very sorry and I’m sure, should you give enough of yourself to doing good works, you can distract yourself from poor fallow Uterina and the agonizing monthly tears she sheds for your sorry state.

The Indian Girl and the Negress: The Lucky Ones!

Do you suffer from cramping? Bloating? Fatigue? Headaches? Well, that’s what you get for having a reasonable allotment of human rights, a housemaid, and a full tummy.

Take it from James Craven Wood, who says in his 1894 A Text-book of Gynecology, “Menstruation should be as painless and as normal as defecation.” Well… yes, in a way, I suppose. That wouldn’t be the first analogy I’d use, but then again I am not a doctor. The point is, if your menstruation pains you, it’s partially because you didn’t have the fantastic good fortune to be born a woman of color in the nineteenth century. Your darker-skinned sisters are having a fine time of it. They were blessed with the marvelous constitution that accompanies brutal relocation and forced labor.

Says Wood,

“The Indian girl, and, we are told, the Negress in her native abode, do not suffer in the least, notwithstanding the fact that at all times they are subjected to the most severe exposure and exercise. Their systems have become inured to hardships by the environs, which have exerted a hardening influence, not only upon them, but upon their ancestors through countless generations.… The influence of hard work and simple fare upon the quantity of hemorrhage is incontestable. The girl or woman reared properly and endowed with a constitution such as she is entitled to as a birthright, can stand exposure during menstruation which would be decidedly hazardous to her more delicate sister.”

Wood’s basis for this theory is stated clearly in his first sentence, “we are told.” And that’s as good a chunk of medical research as you’re going to get, missy. Citing sources was not considered nearly as important in this era. I think Mark Twain said that. Or Lincoln. Somebody.

Menses Don’t Lie

Many doctors and probably a few farmers and a handful of very intuitive carp of the nineteenth century believed your menstrual flow was directly connected to your personality. Your behavior and attitudes would actually create your physical condition. So, if the previous two problems (unmarried and delicately Caucasian) did not explain your difficult menstruation, there were still a variety of personal failings to consider.

In an 1889 edition of the homeopathic medical journal The Hahnemannian Monthly, a Dr. B. F. Betts suggests medical treatments for various illnesses of the uterus. He details what sort of women are associated with different menstrual cycles:

Menses delayed or scanty: A woman who is often suicidal, tainted by syphilis, nervous, and “has light hair.”

Menses too frequent and too profuse: A woman for whom thinking too hard will trigger blood flow, found in “fat, flabby, and scrofulous [run-down-looking] patients.”

Menses irregular: “Weak, nervous, languid; desire to remain quiet.”

Menses that cause vertigo and ringing in the ears: “Weak, delicate women who perspire easily and are very susceptible to draughts of air.”

Menses offensive, acrid, too frequent, and too profuse: “Fat and anemic, apprehensive, timid, unable to sleep after 3 a.m.”

Menses very dark: “Nervous women.”

Menses dark, thick, profuse, and exhausting: “Haughty women, who treat their friends and equals as inferiors.”

In conclusion, women are just awful, and periods prove it.

One redeeming note about all of these publications is that although men took it upon themselves to tell women how to manage their offending bodily functions, they all insisted it was a mother’s duty alone to tell her daughter of the coming change in her body. Without exception, they railed against the “foolish modesty” that stayed a mother’s tongue and left a girl believing herself deathly ill with no one to turn to, since she’d been taught the foulness of even thinking about that part of herself. Doctors told of girls stuffing their private parts with freezing snow to staunch the flow they thought fatal. Only a cruel mother would allow her beloved child to endure anguish like that, they concluded.

Look out, boys. Lotta’s headin’ into town and Aunt Flo is ridin’ shotgun.

We should leave the business of menstruation on that peculiar high note. It’s comforting to know that these educated and, one might even say, preposterously confident men believed there were some things in a woman’s life best learned from other women. Of course men still had to remind the silly darlings of their duty to instruct younger women about these intimacies. But now that we know just how horrific a woman’s monthly sickness actually is, we can hardly blame her for being a bit skittish and absentminded, can we?