CHAPTER 1

Everyday life in a remote Aboriginal settlement

The starry night sky above us, we had arranged piles of blankets and pillows so that we could lounge comfortably on top of our mattresses, a fire crackling cheerfully on the side, and a television set on a long extension cord in front of us. We were watching Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, a game show popular in Yuendumu. Tamsin, a seventeen-year-old Warlpiri girl, came to join our row of bedding, nestling down between her mother Celeste and myself. ‘Who wants to be a millionaire?’ the game master asked on the television. ‘Me’, ‘me’, ‘me’, the residents of the camp shouted in reply, Tamsin loudest of them all. ‘What would you do with a million dollars?’ I asked her.

Tamsin: I would build a house.

Yasmine: Where?

Tamsin: In Yuendumu.

Yasmine: And what will it look like?

Tamsin: It’s really, really big, with lots of rooms, and every room has furniture in it. Sofas, and beds, new blankets, and tables and chairs. And every room has a stereo in it, and a television, and a video player and a playstation.

Yasmine: And who will live in that house?

Tamsin: Me.

Yasmine: And who else?

Tamsin: Nobody else. Just me!

Yasmine: Won’t you be lonely?

Tamsin: No, I’ll have peace and quiet. And I’ll keep the door locked. I won’t let anybody in.

The fantasy of winning a million dollars provides a license to dream about what one desires most. Since ever having access to so much money is utterly unrealistic for most Warlpiri people, the dream might as well be about something one will never get, acquire or achieve. In Tamsin’s case this was her own new house filled with large numbers of desirable items such as new blankets, video recorders and playstations. This is understandable enough, given the impoverished material circumstances in which people at Yuendumu live and the long waiting lists for council-provided housing. Her desire for material goods is identical to that of many other Warlpiri people.

But there was more to the fantasy. As I lay on those swags, cosy not only because of the warmth of the fire, the blankets and pillows, but also in the presence of the people around me, my body comfortably snuggled close to those of my friends, curled around Tamsin on one side and with Greta behind me, her arm slung over my waist, Tamsin’s desire to be alone in that dream house struck me as extraordinary. Living in the camps of Yuendumu, I had taken quite some time to get used to being constantly surrounded by and involved with other people all day and every day. Whenever I sat down with a book in the shade of a tree, people immediately joined me and started conversations, assuming I was sad or lonely. Once I went to get firewood on my own, only to get into trouble afterwards. I could have been bitten by a snake! Gotten lost! Been assaulted by strangers or spooky beings! And had I forgotten the people who were looking after me, those who were responsible for me? Imagine the trouble they would get into if something happened to me!

No, being alone was never an option in Yuendumu. And after a while I came to appreciate the constant company, and even to depend on it. Once I stayed in a friend’s guestroom in Alice Springs, and woke up panic-stricken in the middle of the night, because I couldn’t hear anybody else breathing!

Of course, relations weren’t always as smooth as they were on that evening we were watching Who Wants To Be A Millionaire. Fights broke out frequently and then people left the company of those they were fighting with, but only to join others, never to be alone.

Yet here was Tamsin yearning for a space that was hers and hers alone. While her desire for material goods can be understood literally, the space inside the house requires, I believe, more interpretive work, and can be better ‘read’ in ways suggested by the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. His The Poetics of Space (1994, first published in 1958) is a psycho-philosophical treatise on the house as a primary metaphor in thoughts, memories, and dreams. He describes how it is ‘reasonable to say we “read a house,” or “read a room,” since both room and house are psychological diagrams that guide writers and poets in their analysis of intimacy’ (1994: 38). This is not only true of poets and writers. Tamsin’s fantasy house strikes me as an excellent if puzzling ‘diagram of her analysis of intimacy’. The house in her fantasy is a space she can only dream about. It is a space where she is independent: the house contains quantities of everything she needs. It is a space filled with peace and quiet, where she is happy. It is a space where she is in control; she holds the keys to the doors.

Why would a seventeen-year-old Warlpiri girl living in Yuendumu formulate such a curious desire? The answer lies, I believe, in considering more deeply the issue of intimacy. What does Bachelard mean by ‘intimacy’ when he calls the house a diagram of an analysis of intimacy? As I understand him, he conceptualises intimacy as a kind of innermost protected idea of selfhood, a way of being and seeing oneself. If we are to truly understand what Tamsin expresses in her fantasy, we need to understand not only the wished-for intimacy, but how and why this differs from more common Warlpiri forms of intimacy. These find expression in the ways in which Warlpiri people define their personhood in everyday social practice by relating to each other. Exploration of such Warlpiri expressions of intimacy opens paths towards understanding the contradiction inherent in Tamsin’s wish for a house of her own, with keys to lock the doors so she can exclude others, while at the same time defining herself through relating to others. This contradiction arises, I contend, out of the dynamics between the social practices of contemporary everyday life in a remote Aboriginal settlement and the realities of living in a First World nation state.1 Exploring these dynamics and the meanings encapsulated within them is the central aim of this book.

My way of approaching this aim is to further problematise, question, and unpack the metaphor which encapsulates the space of intimacy of Tamsin’s fantasy: the notion of the house. Bachelard (1994: 6) aims to ‘show that the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams of mankind’. I do not wish to diminish what he says about the house; in fact, I believe its metaphoric potency cannot be emphasised strongly enough. However, I take issue with extending this metaphoric potency to all of ‘mankind’ in a unified way.

While Bachelard shows how the house has great metaphoric potency, I find that the essay ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’ (1993, first published in 1951) by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger best explains why this should be so. He identifies the ways these three practices are related to each other. In order to dwell, one has to build; and the way one builds mirrors the way one thinks: which in turn is inspired by the way one dwells, creating a processual cycle. This goes beyond Bachelard, who asks: ‘if the house is the first universe for its young children, the first cosmos, how does its space shape all subsequent knowledge of other space, of any larger cosmos?’ (Bachelard 1994: viii).2 In Heidegger’s idea there is no unidirectionality; instead he demonstrates how the three practices are interdependent and how, as a series, they encapsulate ideology; and by that I mean nothing more or less than a socio-culturally specific way of looking at the world and being in the world. The ideology, or the multidirectional connectivity between the physical structures in which people live (building), their social practices (exemplified through their practices of dwelling) and their world views (thinking), can be expressed – and here Bachelard again is useful – in metaphors of great potency. In the Western context, this ideology can be symbolised by a stereotypical house:

In his essay, Heidegger commences his theory on building–dwelling–thinking with the assertion that the verbs ‘to build’, ‘to dwell’ and ‘to think’ stem from the same etymological root in Germanic languages. From this alone we can infer that Heidegger is concerned with a socio-culturally and historically particular series of building–dwelling–thinking, valid in Germanic or, more contemporarily, Western contexts. The etymological link in his particular example is interesting but dispensable; significant are the meanings he attaches to the series, meanings which substantially transcend the linguistic level. My point (not necessarily Heidegger’s) is that it is more than likely that the same series may exist with different implications but equal potency in other (non-Western) contexts, independent of the presence or absence of etymological links. If this is true, then such ideologies, or the interconnectivity between the physical structures in which people dwell, their social practices and their world views, can be metaphorically encapsulated in symbols for different physical structures of domestic space. Such symbols representing the physical structures express the ‘integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams’ of the people who live in them. In short, each such symbol can be taken as a metaphor embodying the socio-cultural series of building–dwelling–thinking and encapsulating a particular way of looking at and being in the world.

I propose that in the Warlpiri context the term that encapsulates the parallel metaphoric load to the house in the Western context is ngurra — a conceptual term of profound depth, encompassing multiple levels of meaning ranging from the mundane to the ontological. Most immediately, ngurra can be translated as camp, burrow, or nest; but this meaning of ‘shelter’ expands to include place, land, country, and fatherland. On an emotional plane ngurra means home, as well as the place with which a person is associated by conception, birth, ancestry, or ritual obligation. Socially its meanings encompass the people living in one camp, being one family, being from the same place. Temporally, ngurra is a label for the period of twenty-four hours, and is used to designate numbers of days or nights. Lastly, it is used for socio-spatial designations during ritual. Warlpiri people have two iconographic representations for ngurra:

concentric circles which may serve to represent the entire range of meanings listed above, or any context-specific ones; and

a combination of one horizontal and a number of vertical lines.

The latter iconographic design always denotes a specific camp in which particular people have slept, with the horizontal line depicting the windbreak and each vertical line standing for a person.

Following the Warlpiri iconography, throughout this book I use the first design of concentric circles and the Warlpiri term ngurra when I refer to the entire range of meanings, and the Aboriginal English term camp and the iconographic depiction using lines when referring to a particular camp or when reproducing maps of particular sleeping arrangements. In short, a camp is one of many possible manifestations, and represents only one of a number of levels of signification contained within the term ngurra. Or, put differently, a camp in this regard is the equivalent of an actual house (rather than the house as symbol). In terms of the series of building–dwelling–thinking, a camp and an actual house are both manifestations of two aspects, building (the material structure) and dwelling (social practices of relating to domestic space). Ngurra, on the other hand, encapsulates the entire Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking; as a term, concept and metaphor it contains Warlpiri ideology in exactly the same way as the metaphor of the house does in the West. From this it follows that we can say that

represents building–dwelling–thinking in the West, and

represents building–dwelling–thinking Warlpiri way.

Since the creation of the settlement of Yuendumu, sedentisation and the advent of Western-style housing as entailed in the processes of colonialism and post-colonialism, Warlpiri people have been experiencing an intersecting of these two series of building–dwelling–thinking. This intersection shapes the contemporary settlement everyday, those things that people consider normal, routine and mundane; it shapes contemporary Warlpiri ways of being in the world. It also shapes Tamsin’s fantasy. Here she is, wishing for a house, her own, just for herself, and smack-bang in the middle of Yuendumu, no less, while cosily snuggled up to her mothers in a camp. Taking into account her way of being in the world, her experiences of settlement life, her life history, we must ask ourselves whether she wishes for a house and only a house, or whether the imagery of the house in her fantasy also stands for something else.

Like those pictures used in psychological testing, in which, depending on how one looks at them, one sees either an old woman or a young one but never both, houses at Yuendumu, I contend, also have at least two mutually exclusive meanings. The house, which at Yuendumu materially embodies the intersection of the two series of building–dwelling–thinking, in Tamsin’s fantasy is a vehicle for expressing a particular desire; but it can also stand for the expectations which the Australian state has of Warlpiri people.

The framework of the book

If we credit the house with the metaphoric potential which Bachelard ascribed to it, state-provided housing can be viewed as carrying a specific agenda: the imposition of a particular way of ‘thinking’.3 This goes some way to explain why housing, from the onset of the Australian state’s engagement with Aboriginal people, has been and continues to be among the biggest items in Australia’s annual Aboriginal Affairs portfolio budgets, consistently accounting for between 25 and 35 per cent of the total (Sanders 1990: 41).4 Viewed from the perspective of the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking, Yuendumu houses stand for the expectations the state has of Indigenous people — that they become like ‘us’. The always ‘over-crowded’, often dysfunctional and partly derelict houses at Yuendumu become an expression of the Warlpiri ‘failure’ to comply, a failure to be in the world in ‘acceptable’ ways. Yet Warlpiri people want Western-style houses: council discussions of housing allocation are by far the most heated as well as the best attended meetings; and Tamsin, asked what she would do with a million dollars, answers that she wants a house.

Why do Warlpiri people want those suburban houses so badly, seeing that their practices of dwelling and their ways of thinking about and being in the world conflict so starkly with the values that houses are imbued with in the mainstream? In order to understand more fully the nature of the contradictions between the state’s expectations and Warlpiri people’s desires, I employ the lens of the intersecting series of building–dwelling–thinking to the ethnographic data presented throughout this book.

The ethnography of this book is based on the dramas of everyday life as they unfolded in the camps of Yuendumu during my fieldwork, and particularly revolves around the three values that seemed to shape the everyday as I experienced it: mobility, intimacy and immediacy. I suggest that these values (mobility, immediacy and intimacy) are constitutive of the contemporary settlement everyday because they are manifestations of the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking. In order to make this case, to convey a sense of the ‘feel’ of Yuendumu everyday life, to illustrate the interconnectedness between intimacy, immediacy and mobility, and to shed light on the particular socio-cultural forms these take, I provide extensive case studies of significant everyday interactions, situations, conversations, and experiences.

The clues to understanding the ways in which people are in the world and the view(s) they take of the world lie hidden underneath the commonplace, and can be revealed by analysing the everyday. By ‘the everyday’ I mean those things that people consider ‘normal’ and often (no matter whether in an Indigenous or non-Indigenous context) not worthy of reflection. The strength of anthropology as I see it, and here I am drawing on Outline of a Theory of Practice (1977) by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, lies in understanding and explaining exactly such apparently mundane matters as who sleeps where and next to whom; why people are mobile in the way they are; where the boundaries between public and private lie; how food and other material items are distributed; how people relate to each other; and what we can learn from the ways in which people use their bodies. Kinship, ritual, exchange and so forth all can be formulated in esoteric terms, but ultimately, I believe, they need to be understood as grounded in and arising out of everyday social practice. Primarily focussing on the former, anthropology has largely ignored the contemporary everyday of remote Aboriginal settlements.5

The case studies in this book centre around one particular camp (a jilimi or women’s camp) at Yuendumu, and I use them to consider Warlpiri people’s high residential mobility by examining the flow of people through camps. I present examples of Warlpiri sleeping arrangements, which change on a nightly basis, and interpret them as expressions of the current state of social affairs and statements about the person. These discussions are framed with a view of understanding the connections between people and how they are negotiated, reinforced, maintained or broken; or, how Warlpiri ideas of intimacy are lived out in everyday life. I also explore Warlpiri sociality during the day, mapping the movements of people in and out of camps and throughout the settlement, to elaborate how the particular feeling of immediacy, that so characterises the contemporary Yuendumu everyday, is created.

The contemporary everyday, however, cannot be understood without relating it to the ‘before’. The relationship between ‘then’ and ‘now’ entails continuities, changes and ruptures which critically shape the here and now. The most decisive date of rupture in this sense is 1946, the year Yuendumu was set up as a government ration station. Analysis of contemporary everyday social practice at Yuendumu needs to proceed from an understanding of what the situation was before 1946, and what has happened since to affect it. In regard to this crucial date, Warlpiri people themselves distinguish between two types of historical past: 6 the olden days and the early days. The Aboriginal English term olden days is used to label pre-contact and early contact times, characterised by a nomadic lifestyle, a hunting and gathering economy and an elaborate ritual life. Early days, on the other hand, is the period of initial settlement and strict institutional control which brought with it, among other things, Christianisation, sedentisation, and a new economy.

Quite a few people still alive today experienced the olden days, growing up and living in the bush before either coming voluntarily or being brought by force to live at Yuendumu. Others do not remember the olden days themselves and grew up during the early days. Their children and grandchildren, on the other hand, were born and raised in Yuendumu; to them the olden days and the early days are known as stories from the past, and their lives and histories are intricately linked with the settlement of Yuendumu as their home.

Throughout the book, I examine some of the key ruptures, continuities and transformations in social everyday practices that have taken place in the last sixty years or so. I focus on the impact sedentisation has had on social practices relating to domestic space, elaborating on past as well as contemporary residential arrangements, and within this specifically the increased significance of women’s camps, or jilimi.7 I suggest that jilimi and their older female residents have become central foci of everyday social life generally, in particular for young mothers and their children. Also, I establish how life in the jilimi is intensely social, not least since the great majority of people who pass through them are unemployed and live on social security payments. Inclusion of this historical perspective allows me to illustrate how contemporary forms of intimacy, immediacy and mobility are the result of Warlpiri engagements with both the present and the past.

The arena within which I explore these contemporary forms lies in the interplay between Warlpiri people’s social practices and the spatiality of the settlement, which enables me to analyse more precisely the ways in which the two series of building–dwelling–thinking intersect at Yuendumu. The crux of the book, then, is to unveil the meanings contained in Tamsin’s fantasy and through this to elucidate how and why the imagery of the house can serve to express the dilemmas of contemporary settlement life.

Fieldwork, ethnography and key protagonists

I began research at Yuendumu in 1994, and I have returned there every year since. The most concentrated research took place between 1999 and 2001, during which time I lived at Yuendumu for eighteen months. The Warlpiri ‘everyday’ described in this book is different from the everyday of previous decades, and, it can safely be assumed, will be different again from everyday life in the future. I emphasise this temporal dynamic of the ‘ethnographic present’ by using the past tense and the present tense interchangeably in the descriptive parts. The past tense flags that the period of research for this book is over, and things are already changing. People have passed away, children have been born, new marriages have been made and others have deteriorated, and government policies and incomes have changed, as indeed has the physical appearance of Yuendumu. New houses are being built, others have fallen into disuse, humpies (shelters of corrugated iron and bush materials) occur less and less often, there seem to be fewer jilimi and many are smaller than they were in the 1990s, new roads have been sealed, and so forth. The present tense, on the other hand, is used as a literary device to convey the distinct atmosphere of the immediacy of everyday life at Yuendumu.

Fieldwork was conducted in classical participant observation style. Since 1994 I have spent more than three years in total living in camps with Warlpiri people, who, fortunately, insisted on my incessant participation in everything they themselves were involved in. My co-residents, neighbours, friends and I experienced the everyday I describe and analyse, and this everyday was created, lived and shaped by all of us, including me.

There is no point even trying to write myself out of the book. While I doubt that I caused major shifts and changes, my presence and participation was certainly responsible for the crystallisation of certain disputes that otherwise may have lain dormant, and for an increase in options for a number of people through access to my resources, in particular my Toyota.8 The Warlpiri view of Toyotas is that they should run until they die. This meant that as soon as I arrived back in the camp from one trip, other people turned up (or were waiting already) requesting a lift, a firewood trip, or just to go cruising around the settlement. On average, I drove about 1000 kilometres a week. A substantial part of this mileage was taken up by just driving in and around Yuendumu, but we also frequently went further afield. The Toyota loaded to maximum capacity, we went on hunting trips throughout the Tanami Desert; we drove to settlements all around central Australia to visit people’s relatives or to participate in ‘Sports Weekends’; we travelled in large convoys for sorry business (mortuary rituals), women’s business (women’s ceremonies), and business (initiation ceremonies); and of course we often went to Alice Springs (to shop and to visit people in hospital and in jail). Having the Toyota in the field also allowed me to gain a comprehensive insider’s view of Warlpiri mobility.

While participation in such extensive mobility was physically exhausting, immediacy was a challenge in other ways. Immediacy shaped my fieldwork every day in multiple ways, and I struggled to come to terms with it (and in the end, came to miss it very much when away from Yuendumu). Immediacy meant that I could not plan ahead. Specific data collection, language lessons, everything happened when it happened, rather then when I wanted it to happen. Big events (such as mortuary rituals in the case of death) overruled any other activity, but even without them, everything had to be slotted in with what was happening in the settlement on that particular day, and coordinated with large numbers of people and their assorted ideas and desires. Appointments simply did not work. Once I let go of my ideas of scheduling and planning (and believe me, this was no easy task!), once my life and my fieldwork agendas fell into sync with whatever it was that happened on any given day in Yuendumu, I discovered a way of being in the world very different from the one I was used to. There is a fundamental difference between waking up in the morning and knowing what lies ahead and waking up in the morning full of curiosity about what the day might bring. It not only meant experiencing time in new ways, but also entailed a fundamental shift in my ways of relating to others. Immediacy meant that rather than seeking to fulfil my own desires (be they a particular interview, a hunting trip, or listening to olden time stories), I learned to have them fulfilled by fully participating in the collective push and pull of ‘being in the present’.

This, in turn, taught me much about Warlpiri forms of intimacy, of how to know and how to relate to others in Warlpiri ways. Many anthropologists before me have noted the Aboriginal maxim of ‘knowing because of doing’ (rather than through verbal answers), and this is not only true for ritual but also for everyday life (see amongst others Harris 1987; Morphy 1983; Myers 1986a: 294). Only through living with Warlpiri people, through being in the same space and time with them, sharing activities and stories, and, not unimportantly, through submitting to the wishes of others did I learn what intimacy in this socio-cultural context means: a reciprocal awareness of the other as a person, of their life histories, their desires, their quirks, their habits, and a willingness to let this awareness influence how one acts in the world.

Out of the three values underpinning everyday life at Yuendumu, intimacy is perhaps the hardest to convey in a book. To bring some sense of it to the reader, most of the case studies revolve around a small number of key protagonists, with the aim of familiarising the reader not only with Warlpiri social practices but also with a range of actual Warlpiri people.9

Next to Tamsin, these key protagonists of the book are Tamsin’s adopted mother Celeste, Celeste’s mother Polly, and two classificatory sisters of Polly: Joy and Nora. Joy was my first ‘mother’, as her husband, Old Jakamarra, had been the one who when I first came to Yuendumu had given me my skinname [subsection term] ‘Napurrurla’, thus making me his classificatory daughter. This meant that I was henceforth able to work out the ways in which I should relate to all Warlpiri people I met. As I was Old Jakamarra’s ‘daughter’ Napurrurla, Joy Napaljarri became my adopted mother, as did all other Napaljarri women. In the same way, I would now relate to all other women with my own skinname, Napurrurla, as my classificatory sisters, Celeste amongst them.10 Nora, another Napaljarri and hence ‘mother’ of mine, was one of my co-residents in the jilimi (and in some other camps later on), and instrumental in my education about olden days and early days. After I had a fight with Joy, Polly adopted me, and to this day in Yuendumu I am known as Polly-kurlangu, belonging to Polly. These four women were some of my key informants, and those still alive remain close friends, and indeed adoptive relatives.

In this book I introduce different aspects of these four women: how they relate to each other, how they related to others in the camp we were staying at the time, how they presented their selves in the ways in which they positioned their bodies at night, and how they cooperated with some people and fought with others. All of these descriptions are presented by me as author. As the nature of my own personal relationship to each of these women is particular and unique, I here provide sketches in narrative form about the personal ways in which I related to them, recapitulating interactions between these women and myself as they took place around the time we all lived together in the jilimi. These vignettes represent my own portraits of the four women as I experienced them, and hopefully will convey to the reader the nature of our relationships, which, I am sure, has impacted on how I represent them in the case studies throughout this book.

Joy Napaljarri, ‘my first mother’

In the evenings, Joy and I often sat around the fire, telling stories. Many were about other white women Joy grew up. ‘And then I helped that anthropologist, but she left me for that West Camp mob, and that linguist, she left for Leah, and that Women’s Centre coordinator, she left, too.’ Her stories inevitably ended with: ‘And now I got Napurrurla, she is like a real daughter, she’ll look after me for a long time, and when I get my house, she’ll move in, too.’ Joy’s name was right at the top of the list at council; the next house to be built in Yuendumu was going to be hers. ‘When we move into that house, it won’t be like those other houses, our house will have a garden with flowers and an orange tree, and a green lawn. Inside, there’ll be curtains, and chairs and sofas, and pictures on the walls. And everybody will have their own room. One for me and Kiara [her grand-daughter], one for Napurrurla and one for Lydia [her daughter].’ I liked sitting around that fire, in the evenings and sharing dreams — and often it reconciled us after the clashes we had during the day. It was nice to be compared favourably to ‘the other’ Kardiya [Whitefella] women, those ones that ‘left’ Joy. Sitting around that fire, we felt snug, warm and content, looking forward to the future, when our dreams would come true.

In the jilimi, every once in a while, somebody, most often Joy, would decide it was time to clean. ‘This place is a mess, let’s clean up!’ Cleaning means a trip to the shop to buy a rake, a broom, and Ajax. The rubbish in the yard would be raked up and burned, and the bathrooms would be sprinkled with Ajax, scrubbed with brooms and hosed down with water. One time, Joy said to me, ‘Go back to the shop and get some Pine-O-Clean’. When I came back, she opened the bottle, generously splashed it all over the bathroom and stood in the middle of it, her hands on her hips, looking expectant. After a couple of minutes, her face dropped and she murmured, ‘Maybe it only works for Whitefellas.’

In the end, Joy and I did not get along, and I, like all the other white women before me, ‘left’ her. I always felt I disappointed and hurt her gravely. Her biggest dream was having her own house, Kardiya-style, and she knew that on her own she could not create and maintain a suburban dream house in the middle of Yuendumu. Her hope was that my presence, the presence of a Kardiya in her house, would achieve that. We fought a lot, and when she finally got her own house, I decided to stay in the jilimi and did not move in with her. I always felt that for her I was a disappointment in the same way the Pine-O-Clean was. In ads on TV she had seen what it could achieve: clean gleaming bathrooms with tiles in which your face would be reflected. The Pine-O-Clean did not fulfil its promise, that bathroom never sparkled, and I did not move in with her; and thus, although she was so close to achieving her dream of living in a Kardiya-style house, it was always my fault that it did not eventuate.

Celeste Napurrurla, ‘my sister’

The first time I saw Celeste, I was living in Old Jakamarra’s camp and she came over to pick up Joy for a Night Patrol shift. Celeste is small, a head shorter than me at least. There she was, looking fierce in a large black bomber jacket with NIGHT PATROL written in silver letters on the back, swinging a big nullahnullah in her left hand, a black beanie on her head. After she left with Joy I said to Old Jakamarra, ‘Who was that?’ He chuckled. ‘Your sister that one.’

Later, Joy and I moved into the jilimi and Joy resumed working full time at the school’s Literacy Centre. Because of that and her many other responsibilities, she asked Celeste to keep an eye on me and make me tea and damper in the mornings. In retrospect I think the main reason she asked Celeste and not anybody else was that she never perceived Celeste as a threat in respect to her ‘ownership’ of me. Celeste is excellent in arranging domestic matters, but nobody thinks she is too bright when it comes to politics; neither is she pushy. And while Celeste’s value as an anthropological informant is most limited, as a person to hang out with, to live with, and to be around, she is bliss.

Celeste made sure I had a break once in a while. This is not to say that she didn’t have her own agenda. She was working around the jilimi all day long, looking after children and old people there, preparing food and organising firewood and sleeping arrangements, and it was when she insisted I needed a break that she could have one, too. And in the mornings we managed to stay in bed longer because of each other. I kept thinking, ‘As long as Celeste is not up, I won’t need to get up either’. So I spent contented extra minutes in my swag listening to the clatter in the jilimi, pretending to be still asleep, once in a while peeping out from underneath my blankets to make sure Celeste was still asleep underneath hers. One morning as I emerged for a quick glance, she did the same at the same moment. Having caught each other at it, we laughed and she said, ‘Oh, now we have to get up after all’.

One of my favourite memories of Celeste is of a very, very hot summer afternoon when we borrowed a fan and went into her room to have a siesta. There we are lying on the blankets with the fan keeping us moderately cool. Celeste’s steady breathing next to me is as always the most soothing sound. I keep drifting in and out of sleep, once in a while opening my eyes for a glance to the outside. Through the half-open door I can see the roof of the verandah, the wall dividing the verandah from the yard and in between them a strip of blue, blue sky. Occasionally there is a cloud in it, sometimes two; sometimes there is none.

Nora Napaljarri, ‘another mother’

When finally, after many months, I had my big fight with Joy and the two of us stood on the jilimi’s verandah yelling at each other, it was Nora who ended our fight. She was sitting at the other end of the verandah next to a small cooking fire, making tea and damper. In the middle of our yelling, she calmly said, ‘Napurrurla, come over, your tea is ready’. I went and sat down with her, accepting a pannikin full of tea and putting chops on the fire for us. Joy stormed off. When the chops were done, I gave one to Nora and one to Polly and ate one myself. Polly nodded towards the door of Joy’s room and said, ‘Too cheeky, that one. I will be your mother now’, and Nora nodded in agreement. Up until that moment I had not been sure whether the fight with Joy was ‘a good idea’. Emotionally it was more than overdue; rationally I was unsure about the consequences it would have. What I had not counted on was the presence of somebody like Nora, whose experience in politics and negotiations is considerable.

Nora had ‘won’ a ‘medal from the Queen’ for organising Yuendumu Night Patrol, she had been a big business woman, a skilful and experienced singer, dancer, and painter. She was cranky a lot when I lived with her, often because she was ageing too quickly. While very much alive and full of ideas, her bones hurt and walking became more and more difficult. To be limited by one’s own body is most frustrating, and Nora did not give in easily. To have been powerful once and now to be becoming ‘just another old lady’ was very hard for her. In turn, I often found her demands on me a challenge, mainly because they were made with an almost royal air. There was no way to refuse a request of Nora’s. Thus, I would drive her to the shop, to the clinic, to look for her grandson, or to go hunting, and I would bring her meat, tea, fruit, and soft drinks from the shop whenever she asked. And it must be said that she always reciprocated; she would sing songs or perform love magic for me in the evenings, and sometimes she would slip me a twenty dollar note on pension days.

Two years after I left Yuendumu, I rang up, as I often do. This time, Nora was around and she came to the phone to talk to me. She told me about the house she had moved into in the meantime, about her grandsons, her sons and other gossip. Then she said, ‘Napurrurla, I am poor one, your mother has no skirt and no blouse, no shoes and no blankets’. This is the Warlpiri way of asking me to send up some things for her, but as I was broke at the time I had to tell her that I was dolla-wangu — without money. ‘Oh poor bugger, my daughter,’ she said. ‘I’ll send you one hundred dollar.’

Polly Napaljarri, ‘my mother’

The first day of cold time: my sisters and I return home to the jilimi from that day’s hunting. In our absence, the others have cleaned up. We join them in the yard, where there are two fires: one smouldering with lots of thick white smoke in which the rubbish burns, and one on which Nangala is making fresh damper. The white smoke of the rubbish fire against the crisp blue sky reminds me of the potato fires that are lit in my German village in autumn. For the first time in years I feel homesick. One of my grandmothers asks, ‘What’s wrong, Napurrurla?’ and passes my answer on to the others. ‘Napurrurla is thinking of home, little bit sad one, poor bugger.’ Polly, without replying, gets up. She takes a rake lying in the yard and starts to dance with it around the rubbish fire. She dances, first the way Warlpiri women dance in ceremonies, with quivering, slightly bent legs and abrupt movements. Then she starts mimicking the movements of the young girls at disco nights: circling her hips, faster and faster. Her dance becomes more and more lewd. Everybody claps and sings and laughs. At night, when my sisters and I are lying in our swags next to each other, we are still laughing. ‘That Polly, she’s clown woman, that one.’

Some months later. I am in the Big Shop and have just heard the bad news. One of Polly’s nieces has passed away. As I leave the shop, I can hear wailing coming from all directions. I hurry to the jilimi and start hugging and wailing with the women who are sitting lined up on the verandah. As I turn around I see Polly. She is sitting alone, crouched in the cold ashes of last night’s fire. She has already shaved off her hair, and her head and body are covered in grey ash. The only visible parts of her warm, brown skin are the tracks on her cheeks made by the flood of tears. Her wail pierces the afternoon air.

One day in summer, as I hang up my laundry on the barbed wire in the yard strung between poles as a clothes line, Polly comes over. There are wet blankets on either side of us and it is like standing in a tunnel. Polly is not lively, demanding, noisy or intimate, like most of the other women. She is quieter, and she mainly watches, mostly from a distance that she herself determines. Sometimes she looks like a young girl and sometimes she looks as old as she must be. She has had two husbands and eight children of whom four have passed away. She has twenty-two grandchildren and nineteen great-grandchildren. In the tunnel of blankets, she comes towards me, touches my head, says ‘My daughter’, and then she is gone.

Yuendumu

Having introduced the key themes and the main protagonists of this book, what remains is to set the scene by introducing the settlement of Yuendumu.11 Located in central Australia, Yuendumu is situated about 300 kilometres north-west of the town of Alice Springs, in the south-eastern corner of the Tanami Desert that stretches from the Northern Territory towards Western Australia. Before sedentisation, Warlpiri people lived throughout the Tanami Desert, in an area roughly extending 500 kilometres to the north-west, about 250 kilometres to the north and 200 kilometres to the south of Yuendumu, and bordered in the east by Anmatyerre country. Warlpiri people had some previous experiences of engagement with non-Indigenous people from intermittently living and working at the early gold mines in the Tanami, the Wolfram mine at Mission Creek, and Mt Doreen pastoral station, and from the horrific 1928 Coniston Massacre (see Michaels 1987; Hinkson et al. 1997).

The first step in the government’s effort to institutionalise sedentisation of Warlpiri people in the area was the setting up of three Warlpiri government ration depots by the Native Affairs Branch: Yuendumu, Warrabri (now called Alekarenge) and Hooker Creek (now called Lajamanu). Thus was the settlement of Yuendumu born in 1946. Long describes the development of such postwar settlements as aiming to

control the shift of Aborigines to towns; to develop the potential of the reserves; to train the Aborigines in order that they might contribute to the development of the reserves in particular and of the country generally; and to provide health services to the Aborigines. (Long 1970: 199)

During the 1950s, a Baptist Mission was established at Yuendumu, and for a period of a few years this mission had charge of the management of the settlement. The mission ran a store, a school and a clinic, and later a kitchen was added for communal meals. In the mid-1950s a government supervisor took over the administration and operation of the settlement. Also around that time, the Yuendumu Cattle Company came into existence under government ownership and with workers’ wages paid by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA).12 In 1959 social security legislation was passed to include Aboriginal people, and from 1966 pensions and family payments started flowing to them. However, payment was often made via third parties, and unemployment payments were not generally paid in remote areas. A push to have ‘direct’ payments was instituted by Social Security and Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bill Wentworth in 1968, a year after the 1967 referendum that led to the Commonwealth Government assuming responsibility for various Aboriginal issues (see Sanders 1986: 115–16). At Yuendumu, direct and full payment of social security entitlements came into effect in 1969; simultaneously communal meals and the issuing of blankets ceased. In 1978 the first elected Yuendumu Council assumed responsibility for settlement administration after the withdrawal of DAA officials.

Of these developments, the direct receipt of social security has been identified by most social scientists as the single most significant factor determining the economic status of Aboriginal people and their relationship to the state.13 Having carried out research in the late 1970s, Young wrote in relation to Yuendumu:

the town has virtually no economic rationale. It is neither a market town, a mining centre, nor a centre for communications — functions which have been responsible for the growth of other towns in the [Northern] Territory. It remains dependent on the rest of Australia for almost every cent its community spends, and every article consumed (Young 1981: 56).

During Young’s research, 19 per cent of the Indigenous population at Yuendumu received wages; during my research, if CDEP work (Community Development and Employment Program, a federal-government-run ‘work for the dole’ type program for Indigenous people) is included as wage labour, the number was around 29 per cent, or, put differently, Yuendumu had a 71 per cent unemployment rate. This stands in bleak contrast both to the overall Australian unemployment figures (around 6 per cent at the time of research), as well as to the overall Aboriginal rate, which Sanders estimated to encompass 44 per cent of non-employment income (Sanders, 1994: 1003). At the time of writing, there is much uncertainty about these financial arrangements, which were targeted in the Liberal Federal Government’s ‘NT Intervention’ in the second half of 2007 (see Altman and Hinkson 2007 for descriptions and critiques). While I am here not concerned with the reasons underlying Yuendumu’s extremely high rate of unemployment, they do present a significant context for the ethnography. The lack of employment is a distinguishing factor of life at Yuendumu; it is not only expressed through statistics but manifested, as I attempt to show throughout the book, in the ways Warlpiri people live their lives (see also Musharbash 2007).

Today, there are between 500 and 900 Indigenous residents living at Yuendumu, most of them Warlpiri people (and small numbers of Anmatyerre and Pintupi people).14 An additional 100 residents are non-Indigenous. Socially, culturally, and socio-economically speaking, Aboriginal people, locally called Yapa, and non-Indigenous people, locally called Kardiya, constitute two distinct populations.15 (Note that I follow this local terminology throughout the book, and employ the terms ‘Kardiya’ and ‘non-Indigenous people’ to refer to local non-Aboriginal people and the terms ‘Yapa’ or ‘Warlpiri people’ for local Aboriginal people.) In the main, Kardiya are living and working in Yuendumu as service providers. Except for Yuendumu Council, which always has a Yapa president (but a Kardiya town clerk), all organisations and institutions at Yuendumu are managed by Kardiya staff (see Appendix for descriptions of these organisations and institutions).

During the early days, Yuendumu had at its centre a gardened area adjacent to the houses of the Missionary and the Superintendent. Known as the Park, this area became flanked by an increasing number of Kardiya staff residences and buildings for Yuendumu’s growing number of institutions (the school, the store, the soup kitchen, the clinic, and so forth). The residential arrangements for Yapa were located at some distance from the Park. Hinkson quotes two Yuendumu men describing early developments of settlement at Yuendumu:

… in those days, the houses were just a few and only kardiya were living in the houses. But us, we used to live out in the camps or humpies. We never used to sleep close to the houses or the settlement at that time. We used to be a couple of miles, or at least a fair way from the settlement and the houses. For water, the women used to come and collect water with buckets and billy cans, in the evenings and in the mornings. […]

… kardiya doesn’t want yapa to come in close up because they might steal something. And yapa doesn’t want to come in (Japanangka and Japangardi quoted in Hinkson 1999: 18).

Stories I was told confirm that in the early days there was a mutually maintained separation between Warlpiri people living at a significant distance from the centre of the settlement and non-Indigenous staff living in houses and working in buildings located around the Park. During these times, Yapa used to live in traditional shelters built out of bush materials, sometimes augmented by corrugated iron and sackcloth (so-called humpies). Above and beyond the spatial ordering of Kardiya living in centrally located houses and Yapa living in camps and humpies surrounding the settlement, the locations of Yapa living quarters followed the cardinal directions from which people had originally come ‘in’ to the settlement. Munn describes this spatial ordering in the mid to late 1950s thus (see also Meggitt 1962: 55):

Mt. Doreen, Mt. Allan (and Coniston), and Vaughan Springs are areas that represent for the Warlpiri general regions in which different sections of the Yuendumu community based themselves in the recent past […]. The camps of each segment are oriented accordingly: Mt. Doreen Ngalia camp to the west or north-west, and members of the northern community of Waneiga Warlpiri camp with them; the Mt. Allan Ngalia (also linked with Cockatoo Creek near Coniston) camp on the east or south-east of the other camps; the Vaughan Springs (and Mt. Singleton) people camp in the south-easterly clusters (Munn 1973: 11).

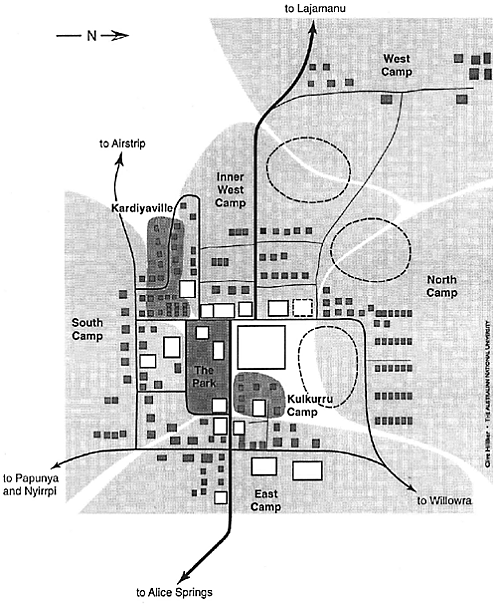

With the advent of the provision of housing for Aboriginal people at Yuendumu, more substantial residential arrangements began to surround the central administrative area, bringing Yapa closer to the settlement from their corresponding quarters and into more permanent structures. These structures (originally crude one- and two-bedroom huts with communal ablution blocks; see Keys 1999 for details of structures and history of housing at Yuendumu) were arranged in clusters, and over time these clusters became named and suburb-like entities. Originally there were four such ‘suburbs’, named after the cardinal directions as seen from the Park: East Camp, South Camp, West Camp and North Camp. (I spell Camp with a capital ‘C’ when referring to one of Yuendumu’s ‘suburbs’, and with a lower case ‘c’ and in italics when referring to individual residences, camps.) Much has been made of this socio-geographical patterning of Yuendumu’s four Camps, and more recent ethnographies have perpetuated the earlier observations by Munn and Meggitt (see amongst others Michaels 1986, 1994; Rowse 1998; Young and Doohan 1989). Jackson for example, obviously picking up on earlier reports by Meggitt and Munn, discusses location as an index of social identity and claims that ‘in Yuendumu, for instance, people from different parts of the country live in different quarters’ (1995: 19).

By claiming that orientation to traditional country determines residency, the four Camps have effectively been presented as not only residential units but as social units based on shared country affiliations. If this was the case originally, it is not true today. Life histories reveal that most Yuendumu residents have lived in different Camps at different times of their lives, with their residential choices motivated by a multiplicity of reasons, most of which do not have anything to do with country affiliation.16 Looking at the composition of any one Camp today makes clear that its residents originally came from a number of areas. Moreover, the residential compositions of Yuendumu’s Camps are in constant flux. The two interrelated issues of slow encroachment towards the Park and the splitting and growth of further new Camps compound this.17

Nowadays, Warlpiri people live in and name six Camps at Yuendumu: North Camp, South Camp, East Camp, West Camp, Inner West Camp, and Kulkurru Camp (see Figure 2). West Camp and Inner West Camp are separated by a football oval and have both independently grown so much that they are now considered to be two separate ‘suburbs’, or Camps. However, Kulkurru Camp is particularly pertinent, as it is the most recent. Kulkurru is the Warlpiri word for ‘inside’; and this Camp is right next to the Park. Houses in what is now called Kulkurru Camp used to be exclusively occupied by non-Indigenous residents, but over the last decade or so Warlpiri people have moved into some of these houses, showing that the encroachment on the Park is continuing. Significantly, it was around the time that Warlpiri people moved into this part of Yuendumu that it acquired its Warlpiri name.

An inverted development is currently taking place in Yuendumu’s south-west, in an area nicknamed Kardiyaville by some of the non-Indigenous population, because it has by now the largest concentration of non-Indigenous people and also experiences the greatest growth of new houses designated for non-Indigenous use.18 Kardiyaville is a cluster of staff houses owned by the Department of Education and the Yuendumu Council, and more recently also by Warlpiri Media, the Mt Theo Substance Misuse and Youth Program, and the Clinic. Kardiyaville is located between Yuendumu’s South Camp and Inner West Camp.

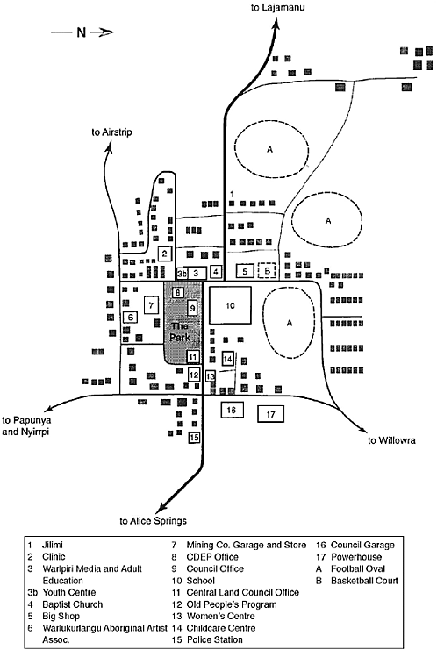

So what is Yuendumu like today? Except during the big summer rains, the drive from Alice Springs to Yuendumu takes three to four hours. The Tanami Road (which connects Alice Springs in the Northern Territory and Halls Creek in Western Australia, crossing the Tanami Desert) is not the rough track it once was; the first half between Alice Springs and Yuendumu is bituminised, and the rest is wider and is graded more regularly than before. More Yapa have cars than even a short time ago, and bigger cars as well, and there is a regular flow of traffic between Yuendumu and Alice Springs. The Yuendumu turn-off from the Tanami Road leads down two kilometres of partially sealed road, now flanked by small African mahogany trees planted by local CDEP workers, past the Police Station, and some occasional humpies, into Yuendumu’s East Camp, and continues towards the Park. There the corrugated tin ruins of the old soup kitchen still stand, but are surrounded by an ever-growing number of newer buildings: the Old People’s program, the new Council building, the new clinic (see Figure 3). On weekdays this area is bustling. People walk along the four streets flanking the Park, on their way to one organisation or another, to the shop, or the post office. Government and Yapa Toyotas drive around, picking up and dropping off people. Beyond the Park, in the Camps, the red Tanami sand is more prominent, a reminder that Yuendumu is indeed a desert settlement. Around the Yapa houses there are the obligatory packs of camp dogs, people sitting in groups in the shade or around their fires, and little kids running around playing. Music, both Yapa and Western, echoes from many of the houses, as well as from cars driving past. If it is windy, a small whirlwind might sweep through, carrying with it more red sand, empty chips packets, and perhaps someone’s laundry. Kardiya houses are quieter and have higher fences, and some have gardens, religiously watered by their owners in an attempt at defying the desert.

Figure 2: Spatial Camp divisions at Yuendumu

Figure 3: Yuendumu settlement (see Appendix, p. 158 for description of main organisations listed here).

All in all, Yuendumu is very much a typical central Australian remote Aboriginal settlement. It is bigger than most — some say it is the biggest in central Australia. And, of course, having started as a government ration station rather than a mission has its own implications, as does the fact that it accommodates a Baptist mission rather than some other denomination. A crucial difference between Yuendumu and most other settlements is that most of its organisations and institutions are independent of the council, meaning that many are more dynamic than their counterparts elsewhere, and also that Yuendumu has a much higher Kardiya population than most other settlements (both in total numbers and in proportion to the Yapa population). In the camps however, these differences are hardly noticeable. Accordingly, much of what is presented in this book did take place at Yuendumu, but could have happened in any one of many other remote communities.