CHAPTER 2

Camps, houses and ngurra

The realities of everyday life at Yuendumu are characterised by the intersection of the Warlpiri and the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking, a highly complex, ongoing and multidirectional social process. A first step towards understanding this process, and hence, the meanings contained in, expressed by and created through the contemporary everyday, lies in analytically disentangling different strands of the intersection.

I begin this work of disentangling by drawing on some anthropological analyses of the relationship between meaning and domestic space. These originate from the vast anthropological literature on the socio-cultural significance of structures of dwellings, beginning perhaps, with LH Morgan (1965, first published in 1881).1 However, this literature has two shortcomings in regards to conceptualising how Warlpiri people interact with Western-style state-provided houses, which need to be acknowledged.

First, this literature has generally taken the ‘house’ as a key symbol expressing world views. Put differently, anthropologists have displayed an overwhelming tendency to focus on ‘the house’, while other forms of domestic structures, such as camps, igloos, caves, caravans and so forth, have largely been ignored. That is to say, anthropologists working with people who have domestic structures resembling a Western house (dwellings possessing walls, doors and ceilings) have undertaken studies in this vein, whereas anthropologists working with people living in differently structured dwellings have rarely focussed on issues relating to domestic space. Some might argue that dwellings that are unlike houses do not lend themselves to such analyses, but my own view is that this trend relates anthropologists’ own inclinations. This can partly be explained by reference to the work of Heidegger and Bachelard, both of whom give good reasons why the Western mind (and hence, most anthropologists) favour the house. This book is an attempt to show that other types of dwellings, in this case the Warlpiri camp, carry as much meaning and in similar ways.

My second misgiving about the anthropological literature about domestic space is that much of it favours structure over social practice. Most studies identify the way in which a house represents the cosmos, for example, and pay little or no attention to the ways in which people live in these dwellings. Or in regards to Heidegger’s series of building–dwelling–thinking, many anthropologists draw connections between building (the physical structures) and thinking (the ways of being in and conceptualising the world), but they ignore dwelling, the ways in which people relate to domestic space in everyday life through their social practices.

The first anthropologist to pay serious attention to the centrality of social practice and bodily movement to the structuring processes was Bourdieu, in his landmark essay ‘The Kabyle House or the World Reversed’ (1990, first published in 1970). His approach generated a new tradition of anthropological analyses of social practices, emphasising social engagement with domestic space. Two works within this tradition have been particularly influential on my own methods of analysis. The first is Henrietta Moore’s Space, Text, and Gender (1986). Based on her Kenyan ethnography, she aims to shift the conventional focus of deciphering the meanings encoded in space and their relations to social structure, to a perspective focussed on the creation and maintenance of such meaning. The question she asks is: ‘How does the organisation of space come to have meaning and how are those meanings maintained through social interaction?’ (Moore 1986: 74). To answer this, she approaches domestic space as a text which is continually read and interpreted by those who live in it — and also by her as the ethnographer. This allows her to analyse change as situated in a web of new readings of new and old practices (rather than simply emphasising new developments, such as, in the case of her ethnography, the introduction of square rather than round houses). Further, she examines how social practice (beyond mere ‘readings’) produces and reproduces meanings of structured space. Her multilevelled and stimulatingly complex interpretation of domestic space is particularly relevant to the analysis of contemporary Warlpiri engagements with domestic space.

The second is Robben’s analysis of the relationship between social practice and spatial ordering in the houses of canoe fishermen and boat fishermen in a Brazilian town (1989). Although these canoe fishermen and boat fishermen live in architecturally identical houses, they read and employ the spatiality of their houses in divergent ways, pointing towards the incessant appropriation of meaning through social practice:

People have to dwell in a house in order to reproduce the habitus objectified by it. How they dwell is influenced by their early childhood socialization, the architectural structure of their present living quarters, and the nature of their activities and social interaction outside the domestic world. House and society are not only produced and reproduced in domestic and societal practices through a process of structuration, but they also continually generate and regenerate one another in a structurating dynamic (Robben 1989: 583).

His point is pertinent in regard to contemporary Warlpiri uses of and ways of relating to domestic space. Today many Warlpiri people live in houses which architecturally are the same as houses found throughout suburban Australia, yet Warlpiri people dwell in them in quite different ways than do suburban Australians. Robben’s approach suggests how to conceptualise the meanings behind different practices in similar dwellings.

Following Robben’s and Moore’s cues, I first examine the structural, the spatial and some of the conceptual properties of camps and houses, as well as their interplay at Yuendumu from the olden days to the present. I begin this process of untangling with a description of the structural properties of olden days camps, which leads to a discussion of the values underpinning the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking. I contrast this with the values inherent in the Western series and through this lens of values examine the introduction of housing at Yuendumu and its effect on contemporary Warlpiri practices of relating to domestic space.

Olden days’ camps

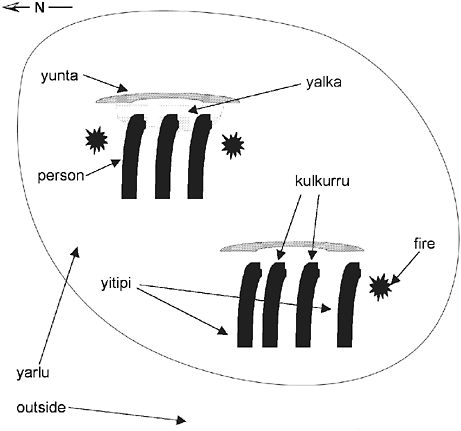

Before sedentisation Warlpiri people lived a highly mobile hunting and gathering lifestyle, travelling across the Tanami in bands of ever-changing composition.2 Before nightfall, the people who formed a band at any one time arranged their sleeping quarters. While the position of these camps changed depending on where a band was at a particular time, the shape these camps took was always the same, and highly structured. People did not lie down at random, but every night they reproduced the same structure, or building in Heidegger’s sense. This was made up of windbreaks, rows of sleepers, and fires. Figure 4 uses Warlpiri iconography to depict a typical olden days’ camp, and delineates the named spaces within it.

Yunta

In its most restricted sense, the term yunta is used to denote a windbreak (see also Keys 1999: 44–6; 165–71). A windbreak is constructed out of leafy branches, either piled on top of each other to create a low, thick wall, or (especially when also used during the day for shade or when particularly windy) dug into the earth so they stand upright and are interwoven with further horizontal branches. The windbreak is oriented to the east of the sleepers’ heads, stretching from north to south. That is, if at all spatially possible, people sleep with their head to the east and their feet to the west. Often this arrangement shelters people from the prevailing winds, and it keeps sleepers’ heads in the shade at sunrise; yet environmental factors alone seem inadequate to explain the practice. While Warlpiri people were not forthcoming with explanations as to why it was so, all were adamant that this is the ideal way to sleep.3

Figure 4: The spatial terminology of camps

In a more expansive sense, the term ‘yunta’ also means ‘open living and sleeping area protected from wind by erected barrier on appropriate side’. A yunta is the spatial manifestation of a row of sleepers, and in this book the term is used to refer to the combination of a windbreak, the places for people to sleep sheltered by it, the people sleeping in it, and, if present, fires. In the past, the sleeping places were indicated through moulds in the sand, one for each person, and in winter people kept warm through huddling together and being close to the fires. A camp may be made up of a single yunta, or a number of them. A camp, however, is not only made up of yunta, but also incorporates some of the space surrounding the yunta.

Yarlu

The space surrounding one or a number of clustered yunta is called yarlu, which according to the Warlpiri dictionary means ‘place with nothing on it or over it’. It is thus similar to a yard or a garden in a suburban-style Western house, open space between the public (the street) and the private (the interior of the house). One crucial difference between a yard or garden and yarlu is that the former do not shift their positions (or existence), whereas a yarlu is only there when the yunta and the people sleeping in it are present, meaning it appears with the creation of yunta and it disappears as meaningful and named space when a specific camp is deserted. It is this yarlu space, or rather the boundaries around it, which clarify the distinction between yunta and camp. A single yunta with a bounded yarlu space is a camp; more often however, a camp is made up of a conglomerate of yunta surrounded by one yarlu space.

In pre-contact times yarlu space was often marked by a low mound of earth around the yunta where people had scraped the ground free of spinifex grass and similar plant matter. While there is no other visible boundary marking the extent of yarlu space, people are nonetheless aware of it. It is this often invisible boundary that constitutes the threshold between public space outside the camp and private space inside it. In the absence of walls, doors, doorbells, porches, halls and other similar physical markers of the threshold between public and private, social rules of behaviour structure its crossing.4 One never walks straight to the location of an actual yunta but waits at the outer boundary of the yarlu, at an appropriate distance, anything between 5 and 30 metres away from the closest yunta, to be noticed and then invited ‘in’.

Yalka

Within the yunta, there is a further delineation of space between the windbreak and the heads of the sleepers, called yalka (translated as ‘close to windbreak’ in the Warlpiri dictionary). Although yalka is a long strip of space between the sleepers’ heads and the windbreak, this space is divided up into individual personal spaces. Thus each sleeper in a row has his or her own yalka space, positioned just above his or her own head. These spaces are not physically separated from each other, but there are strong invisible boundaries separating individual portions of yalka. Within the space of a camp, the yalka space ‘belonging’ to a particular person is their most private space, to keep their personal belongings.

Kulkurru and yitipi

Within the yunta, the positions of sleepers are further distinguished in terms of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. Kulkurru means ‘between, on the way, amid, in the middle, midway, halfway’ and is used to describe the position of sleepers in the middle of a row. ‘Kulkurru ngunaka!’ means ‘Lie down in the middle!’. Yitipi means ‘edge, margin, side, outside, on the outer, periphery’, and is the term denoting the positions of the sleepers on the outside of a row, the ones who sleep between the fire on the one side and the kulkurru sleepers on the other. ‘Yitipi karna ngunami’ means ‘I am sleeping on the (out)side’.

Whether a person is a yitipi or a kulkurru sleeper depends on a number of factors. The kulkurru position is considered safer for a number of reasons. It is further away from the fires, which can cause serious harm. It is also believed that if snakes do enter the yunta, one is safer in the middle. Most importantly, there is an emotional element to such positioning, relating to fear of the dark and ‘spooky’ things. At night when it is dark, one does not quite know what is out there, both in terms of animals and people, and in regards to the potential presence of ‘spooky’ beings. Accordingly, the kulkurru position quite simply feels safer, and therefore it is the most socially senior people within a yunta who take up the yitipi positions on the outside — sheltering and protecting the sleepers inside. However, other factors contribute to this choice, such as personal disposition, generational status, one’s relations to others in the same yunta, and so forth.

The number of yunta on any given night in a particular camp depends on how many people are present and the nature of relations between them. The minimum is one yunta, with an open-ended maximum, depending on occasion and location. Generally, even if relations are amicable, yunta considered ‘too long’ will be broken up. This may happen by placing a number of fires in between sleepers, effectively creating more yitipi positions and thereby more yunta. Alternatively, a potential long row may be broken up into a number of separate yunta arranged parallel to each other, depending on the physical features of the terrain, e.g. when camping in a creek bed.

Gendered camps

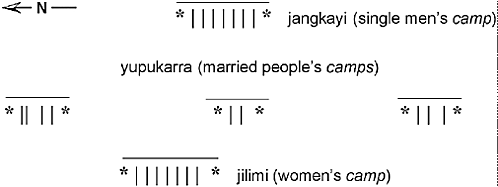

Camps are further differentiated by the gender and the marital status of their residents. Married people sleep in yupukarra, married people’s camps; unmarried people sleep in camps distinguished by gender, women in jilimi, women’s camps, and men in jangkayi, men’s camps. Children sleep in either yupukarra or jilimi, never in jangkayi (for detailed ethno-architectural discussion of the three types of camps, see Keys 1999, 2000).

In the olden days, when a large number of people camped together and all three types of camps where present, their order was prescribed in the following way. The married people’s camps, the yupukarra, were situated in the middle, separated into individual yunta. Located to the west of them was the single women’s camp, the jilimi. Note that a polite way of referring to women is ‘karlarra-wardingki’, ‘those belonging to the west’, and the spatial association between the cardinal direction west and women, and the east and men, features in much of Warlpiri thought as well as ritual organisation. Accordingly, the single men’s camp, the jangkayi, used to be to the east of the married people’s camps. If within the same area, the jilimi and the jangkayi should be located as far from each other as possible (Keys 2000: 126; Meggitt 1962: 76). The iconographic depiction of an aggregation of all three types of camps in one place would look something like the drawing in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The spatiality of gendered camps

Ngurra

In Heidegger’s series of building–dwelling–thinking, the three practices relate in a processual cycle. In order to dwell, one has to build; and the way one builds mirrors the way one thinks, which in turn is inspired by the way one dwells. So far, I have focused on aspects of the first two practices, building and dwelling: we may take the camp to represent the actual structure of Warlpiri dwellings (building) as well as the physical manifestations of practices of dwelling. Camp is the Aboriginal English translation of the term ngurra, which, however, holds meanings surpassing those captured by the term camp. If camp stand for the aspects of building and dwelling of Heidegger’s series, then ngurra stands for the aspect of thinking, encapsulating the values underlying the world views arising out of (and feeding back into) such structures and practices. Ngurra radiates multiple levels of meaning which afford an incipient understanding of how ngurra is a core concept in Warlpiri language and cosmology, and why an analysis of the interconnection between Warlpiri residential patterns and sociality needs to be conceptually anchored around this term.

1) Generic idea of shelter Ngurra is something every person and every animal has. It designates the place where one sleeps at night. For people ngurra takes the structure of the camp; for animals ngurra takes the form of whatever physical structure an animal dwells in, e.g. nest, lair, burrow and so forth. For example, when hunting for honey ants, one first looks for the presence of working honey ants on the ground, follows them to the entries of their ngurra and then digs down to find it. Or in cold time, when goannas hibernate, they are most often caught by digging up their ngurra, their burrow.

2) Place where one habitually sleeps Ngurra in this sense is the term we used to refer to the jilimi when we were all living there. For example, when Celeste was ready to leave another camp we were visiting, she would say to me and the others, ‘Ngurra-kurra yanirlipa’ [literally ‘let’s go camp-wards’, meaning, ‘let’s go home to the jilimi’]. A related term is ngurra-yuntuyuntu, denoting a place where many people lived for an extended period of time, a large and long-term camp, as for example the original camp sites on the outskirts of the settlement, where Yapa lived during the early days before houses were built.

3) Home The emotional bond one can have to one’s ngurra becomes more pronounced in the term’s added meaning of home, with all the emotional depth that can possibly be attached to it. The phrase ngurra-ngajuku (my home) is generally used in this sense, especially in Warlpiri songs, many of which are about homesickness. Ngurra-ngajuku in these songs often stands for Yuendumu (if the song writer is from Yuendumu).

4) Ancestral place Ngurra also designates the idea of the place with which a person is associated by conception, birth, ancestry, ritual obligation or long-term residence: in short, their country, their land. For example, Mawurritjiyi, a place to the south of Yuendumu, is one of Old Jakamarra’s ngurra, a place with which he had profound emotional associations, a place for which he knew the songs and dances, where he had lived in the past, for which he was often pining, and which he consequently often painted in his dot paintings.

5) Family The term ngurra-jinta is used to refer to the people living in one camp, typically close kin. It connotes being one family, of one household, from the same place. Ngurra-jinta presupposes either family connection or long-term cohabitation, coupled with emotional affiliation. The Aboriginal English translation of this term is countryman. Related terms are ngurrarntija and ngurra-wardingki, meaning a person belonging to a certain place, and again, countryman.

6) Ritual division The terms ngurra-kurlarni-nyarra [literally camp–southside] and ngurra-yatuju-mparra [literally camp–northside] are used to designate the two patrimoieties into which all Warlpiri people are divided (these are groupings particularly relevant in the ritual context). The first one is the patrimoiety of all people of the J/Nakamarra, Jupurrurla/Napurrurla, J/Nampijinpa, J/Nangala subsections, and the second one is that of the J/Napanangka, J/Napangardi, J/Nungarrayi, J/Napaljarri subsections. During certain rituals these moieties spatially oppose each other, being positioned on the southern and the northern sides of the ceremony ground respectively.

7) Time Ngurra also stands for the period of twenty-four hours, and is used to designate numbers of days or nights that one would set up camp. For example, when I asked Celeste about the distance to a settlement up north, she answered, ‘Ngurra-jarra’ [literally ‘two camps’], meaning a three-day drive with two overnight stays on the way.

8) Country, the world Finally, ngurrara means country, fatherland, place, land, home. On one level it can be used to refer to one’s own country, e.g. Mawurritjiyi, or more commonly to the Tanami Desert, to the entire Warlpiri lands. However, ngurrara does not only denote the expanse of physical space but everything within it: the people, the animals, the plants, as well as the ancestral beings and spiritual powers contained within the land, the moving clouds, the winds, the stars, the passing of time and so forth.

As this inventory makes abundantly clear, ‘ngurra’ as a term encapsulates a great number of meanings, beginning with the most generic idea of shelter to the incorporation of the Warlpiri cosmos into a single term. ‘Ngurra’ is conceptually extensive and covers the entire spectrum between residential units and cosmological concepts — underpinning my thesis that it is comparable to ‘the house’ in the terms suggested by Bachelard and Heidegger. Put differently, the way in which the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking distinguishes between a camp and ngurra is parallel to the way in which in the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking an actual house is different from ‘the house’ as metaphor. This analytical separation between camp and ngurra is evident also in Warlpiri iconography, in which two different designs are employed in different contexts and carry different connotations (see also Anderson and Dussart 1988; Munn 1966, 1970, 1973; Peterson 1981).

Yapa employ a set of concentric circles (see Figure 6) in the ritual context, in which it constitutes part of body designs, ground paintings, and decoration on ritual paraphernalia, and which incorporates the full range of meanings of the term ‘ngurra’.5

Iconography using one horizontal and a number of vertical lines (see Figure 7), depicting actual camps is commonly used in sand stories, where during everyday conversation the design is drawn into the sand to depict a specific camp in which particular people have slept, with the horizontal line depicting the windbreak and each vertical line standing for a person (see also Munn 1963, Watson 1997). In sand stories, the design is oriented in the same way that the camp spoken about is, or was, oriented in real space.6

Figure 6: Iconography for ngurra

Figure 7: Iconography for camp

Housing policy and (not so) implicit values

Camps were physical manifestations of people’s movements through their country and they accommodated (and created) kin. Camps were erected out of bush materials (sand, branches, fire); when people moved on, their camps were simply left behind, and new ones were erected whenever the band reached a new place. Camps thus embody the core values of mobility, immediacy and intimacy encapsulated in ngurra: core values which clash significantly with those embodied by the house.

Taking an archetypal Western-style house and looking at its conventional uses, those that Westerners consider normal, however they actually live themselves, we find that the primary purpose of the house is to shelter the family. An average family is imagined as a nuclear family, as parents and children. The house is removed from the public world by the front lawn (often also a fence and a porch) and accessed through the front door. The inside is expressive of a spatial order in which separate rooms are reserved for specific functions: a lounge room to relax and welcome guests into, a kitchen to cook in, a dining room to eat in, bathrooms for bodily functions, and bedrooms for sleeping. Bedrooms are the most private space within the house; all other rooms are shared, these are not (with the exception of the master bedroom which is shared by the parents). Bedrooms are not only for sleeping, though; they contain each respective person’s private possessions, and this is also where these persons spend time on their own (apart from sleeping: presumably to read, to think, to have phone conversations they do not want overheard, to daydream, to play, to cry, and so forth).

Contemporary Western-style living revolves around separate rooms for different people with the ideal of one bedroom per person living in the house and some shared rooms for all, separated from the world outside. Houses both symbolise and enable privacy rather than intimacy. Houses are built of heavy materials (corrugated iron, concrete, bricks, wood) and do not move; they are permanent, at least over significant periods of time. Thus fixed in place, houses in turn fix people in place — they foster stability rather than mobility. In terms of materials needed for building, skills involved in building, as well as in terms of maintenance, houses are costly. Houses in this sense foster and express future-orientation rather than immediacy: generally, one needs to accumulate in order to afford to dwell in a house, either to pay rent, or, preferably, to pay off a mortgage with the ultimate goal of owning one’s own house. Similarly, one must budget for household items, furnishings and maintenance.

The values of mobility, immediacy, and intimacy which underpin the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking thus find their opposites in the values symbolised by the house as metaphor and enabled through the house as actual physical structure. The government project of sedentisation, of institutionalising in settlements people who previously roamed freely through their country, aimed to negate and overcome this inherent clash of values, using the house as a ‘civilising tool’.

Following the Second World War, during the so-called era of Assimilation, ‘transitional housing’ was introduced in central Australian Aboriginal settlements. This entailed a vision of Western-style houses as a ‘medium of uplift’, and the idea was to move Aboriginal families through a series of domestic structures with increasing complexity. A ‘first stage’ house usually consisted of one room and a veranda, a ‘stage two’ house included additional rooms and a kitchen, and a ‘stage three’ house had added bathroom facilities, being equivalent to Housing Commission standard. A damning critique of transitional housing can be found in Heppell (1979b). Firstly, he says, living in ‘staged’ houses held little appeal, as they were not at all suited to the local climatic conditions. Made of concrete and corrugated iron, they were hotter in summer and colder in winter than humpies constructed of a combination of bush materials, corrugated iron and canvas, the other type of domestic structure available to Aboriginal people at the time. Another reason why transitional housing as a project failed was due to the fact that no instructions about how to use the houses were delivered, nor did families in actual fact ever move through the stages, as there were never adequate numbers of houses available. Ultimately, Heppel argues, in respect of Western styles of living and Aboriginal styles of living, the transitional housing scheme ‘permits neither set of living practices, nor does it permit a compromise between the two’ (Heppell 1979b: 15). Lastly, he points out the bizarreness of the idea that living Western-style can be taught by moving people through a series of increasingly complex architectural structures; this is certainly not how people in the West learn to live in their houses.

What interests me is the fact that houses are seen as instrumental in what was then called ‘the civilising process’, and in particular, the assumption that by living in a Western-style house, somehow one becomes Western or acquires Western social practices. This assumption was most starkly expressed during the era of Assimilation, but it has persisted.

Following the 1967 referendum, which gave the federal government a clear mandate to legislate on Aboriginal affairs, the policy of assimilation was succeeded by one of integration. While there was a greater emphasis on self-management and equal participation than before, the terms continued to be dictated by the Western majority, and in effect, policies were not inherently different from the former period. They shifted in focus towards those people considered ‘able to integrate’, and housing assistance for them was provided in White suburbs and on pastoral leases. Aboriginal people deemed ‘not yet ready’ were neglected in terms of housing provisions. This period was succeeded by the Labor government’s early 1970s policy which sought to restore to Aboriginal people their lost power of ‘self-determination’. In terms of housing policies this meant that

Labor will give priority to a vigorous housing scheme in order to properly house all Aboriginal families within a period of 10 years. In compensation for the loss of traditional lands funds will be made available to assist Aborigines who wish to purchase their own homes. The personal wishes of Aborigines as to design and location will be taken into account (from the 1971 Launceston conference, cited in Heppell 1979b: 20).

During this period housing became to be perceived as causal within Aboriginal people’s cycle of poverty, the common argument being that ‘without housing, other conventional support systems such as education, health, and employment could have little impact’ (Heppel 1979b: 20). Since the 1970s, in many instances adequate housing has not been provided, neither have the education, health, or employment statistics improved; nor, for that matter, have the arguments changed much. In contemporary times, the provision of housing to Aboriginal people, though not explicitly formulated as a ‘civilising tool’, is a point of contention of enormous proportions. A much-heard contemporary grumble by non-Indigenous Australians is that ‘as long as they [Aboriginal people] don’t know how to appreciate houses, no more money should be thrown at them’. On a more bureaucratic level, to this day education and health officials continue to maintain that improvements in their field can only flow from ‘ordered living’; and health and education researchers continue to channel much of their research activity into housing surveys.

In short, Aboriginal housing policies have always implicitly and often explicitly endeavoured to ‘civilise’, and consecutive Australian governments have assumed that living in a Western-style house will magically turn residents into people with Western-style values and social practices.

Applying Heidegger’s insights to this situation helps explain the failure of these policies in terms of their intended aims. There is no logical reason why provision of one element (building) of the series of building–dwelling–thinking should automatically produce the other two (dwelling and thinking, or social practices and ways of being in and looking at the world). As Heidegger specifies, each element of the series is produced in continual dialogue with the other two; the series as a whole is made up of processual, interconnected, interdependent processes. So rather than state-provided housing transforming Warlpiri people in a predictable and intended way, what happens is that the two series, the Western one and the Warlpiri one, intersect, with reverberations that shape the everyday at Yuendumu.

So how do Warlpiri people relate to houses at contemporary Yuendumu? Today most residences are located in and around Western-style houses, which come in a great variety of shapes and forms, reflecting stages in policy, from one-room tin houses to the latest suburban-style bungalows. The Warlpiri term for the physical structure of a house is yuwarli. However, independent of the kind of physical structure in and around which any Warlpiri residence at Yuendumu is located, it is called camp in Aboriginal English or ngurra in Warlpiri. That is today, a camp can be in a humpy or a suburban-style five-bedroom brick house.7 Practices of dwelling in contemporary camps at Yuendumu follow as well as differ from those of the olden days in significant ways. Accordingly, the Warlpiri use of houses is inherently different from that of Kardiya.

Yapa ways of dwelling in houses

Nowadays, Yapa try to continue to follow the rules of how to set up camp, with many compromises. Yuendumu is a large settlement currently encompassing six Yapa-populated ‘suburbs’, and thus the aggregation of people and physical structures is too large to support the spatiality of the nightly residential separation of men, women, and married people, or of jangkayi, yupukarra, and jilimi (to the east, middle and west respectively). On a smaller scale, the Western-style houses in and around which most camps at Yuendumu are located make it equally hard to sustain this form of spatial ordering. In response, people uphold the rules of gender separation but are lenient with the rules of spatial orientation of gendered camps. Today, many contemporary houses are used either as a jilimi, a jangkayi, or a yupukarra, independent of their location within the settlement.8 Other houses, however, have two or all three kinds of camp located in and around them. In these cases, different gendered yunta occupy different rooms when sleeping inside, or, and more frequently, when sleeping outside, they are located either on different sides of the house, or, at least at some considerable distance from each other.

Houses often interfere with the possibility of orienting the head to the east at night. Here, too, Yapa are pragmatic and if east orientation is possible, they adhere to it. If it is not, people are willing to sleep in other orientations.

In the 1990s, life in Yapa-occupied houses was oriented outwards rather than inward; most activity, including sleeping, cooking, eating, and socialising, took place in the yard and on the verandah.9 This yard-orientedness of Warlpiri people leaves the house available to them as a space to put to other uses. In the pre-contact past people did not have more possessions than they could carry and store in their yalka. Nowadays, Warlpiri people own many more things, and the most prominent use of houses is for storage.

First among Yapa people’s possessions are items of bedding. Each adult person has his or her own swag or mattress, a groundsheet and a number of blankets; and often people have two sets, one for home and one for travelling. Each adult person usually has at least one suitcase or large bag full of clothes, also stored inside houses.10 Further items stored inside are personal belongings, such as towels, pannikins, crowbars, television sets, paints, tools, and ritual paraphernalia. Bedrooms as well as other rooms are used primarily for storage, and only secondarily for sleeping or socialising.11

No matter whether sleeping outside or inside, Yapa continue to sleep in yunta, rows. Sleeping normally takes place on the ground, although some camps have beds in them. However, beds usually change ‘owners’ quickly, and they also tend to move from camp to camp. Instead of moulds in the sand, sleeping positions today are made up of people’s bedding, in the main swags or foam mattresses and blankets laid out on a groundsheet (usually plastic canvas). Rather than using a sheet, mattresses are covered with a blanket, providing extra warmth. Depending on the season and temperatures, people use between one and as many as six or seven blankets on top of them to keep warm. Usually, people do not change into sleepwear at night but keep their clothes on for extra warmth in winter, or take most of them off in the hot summer nights.

The windbreak above the sleepers’ heads today can be anything from a ‘proper’ Warlpiri-style windbreak constructed out of leafy branches, to the wall of a room or verandah, a car or a suitcase, or it may just be there symbolically. Yunta are set up at nightfall, and in the morning the bedding is put out of sight.

These days, at Yuendumu, yarlu space and yard space surrounding a house are often conflated through the introduction of fences.12 When I first came to Yuendumu in 1994, only some public areas and buildings, such as the school and the clinic and some non-Indigenous houses, had fences. Since then, fences have become immensely popular, and most Warlpiri camps nowadays have a fence surrounding them in a square yard-like enclosure. Yapa say they like fences ‘because they keep out dogs and drunks’ — while experience shows they are useless to keep out either.13 The one thing that fences seem to achieve is awareness in non-Indigenous people about camp boundaries. Before the fences were erected, on many occasions I observed non-Indigenous people stumbling right into a camp, crossing the invisible boundaries dividing the public from the private, without ever noticing. Instead of those previous invisible and implicit yarlu boundaries, today, Warlpiri and non-Indigenous people alike often use the fence as the point of negotiation for entry into a camp.

Entry into the yarlu space is negotiated differently depending on degrees of closeness between people inside the camp and persons wanting to enter. If there is a fence, one stands next to it; if not, one stands at an appropriate distance from the closest yunta at the margin of the yarlu. If there is no response from anybody inside the camp, this is equivalent to a door not opened to an unwelcome visitor. Usually, though, people inside the camp acknowledge the presence of the person waiting outside the yarlu and negotiate the situation.

Depending on the relations between the person outside and those inside the camp, and the often known or suspected intentions of the visitor, there are several options. If the person is not wanted inside the camp, or their intentions do not warrant them entering, somebody from inside the camp may get up and walk over to the yarlu boundary where the person is waiting, to discuss the issues at hand (paralleling a conversation at the front door without inviting in). Should entry into the camp then seem desirable, they accompany the person inside and indicate to them where to sit. If the person is welcome into the camp without such negotiations, then people from within the camp simply shout over to them to come in. If the person wanting to enter is in a relatively close relationship to people inside the camp and sure of their welcome, they generally do not wait at the invisible threshold but walk into the camp. However, while they are doing this they address people inside to announce their approach. Often children are used to negotiate an entry of this kind. If the visitor has a child with them, they talk to the child in a clearly audible manner about who is inside the camp: ‘Look, your granny there’. In this case, people inside the camp ‘answer’ by calling out, for example, ‘Little Daryl is coming to visit his granny’, thus implicitly sanctioning the entry. If a person comes visiting without being accompanied by a child but there are children present inside the camp, they greet the children by singing out, for example, ‘Hello little nephew’. People inside the camp prompt the child to reply, for example, ‘Paul, look, your auntie’, again thus sanctioning the passage. If people close to the camp residents come to visit, they simply enter and sit next to the person(s) they came to see.

As in olden days etiquette, today the yunta present a further level of privacy within the yarlu (see also Spatial Diagram of activity areas within the yunta of Warlpiri jilimi in Keys 1999: 168). Yunta are only entered by people actually sleeping in them or people very close to them, as for example Tamsin was when she plopped herself down between Celeste and myself in our yunta, the night we watched Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Without such established familiarity, entering uninvited into yunta space, even if one is inside the yarlu, is either rude or a downright threat. Normally only particularly close people or those invited in enter yunta space.

Equally, the yalka space between the sleeper’s head and the windbreak (today just above, or sometimes underneath, the pillow) remains the most exclusive space within the camp. It is used for storage of essential items and prized possessions, such as water bottles, money, matches, handbags, talismans, tablets, photographs, tobacco and whatever else is important to the sleeper.14 Nobody would ever go close to or take items from the yalka of another person unless explicitly asked to do so. Even though I have slept next to Celeste for years, she still asks me when she wants the water bottle in my yalka, rather than taking it when she is thirsty.

In terms of the yitipi and kulkurru positions of the sleepers within a yunta, nothing has changed, except that nowadays people may actually leave a yunta at night after it has been set up. For example, if a woman stayed with relatives while her husband was away and he returns late at night, she leaves the place she is sleeping at to move back with her husband. Or there might be an emergency somewhere and a person leaves to help out. In these cases, if the person leaving was positioned kulkurru, in the middle, their swag, if they are not taking it with them, is put back into storage, and the remaining swags are drawn together into an uninterrupted yunta. If on the other hand, one hopes to be picked up by a ‘loverboy’ at night, one would, if going to bed at all, sleep yitipi, on the outside, so one can disappear without causing a major disruption. In short, Yapa strive for ‘gap-free’ yunta.

Most significantly, today, as in the past, there is no concept of a single person yunta as a single camp on its own.15 Close proximity when sleeping enables the sharing of dreams (see Dussart 2000: Chapter 4 and Poirier 2005), it deflects possible accusations of sorcery, and most importantly, it prevents ‘loneliness’. To be without marlpa (company) is unthinkable and to be avoided at all costs.16 Sleeping alone is an impossibility, not only because the ‘lonely’ person would be unhappy, but also because should something happen to that person, the ones who left them without marlpa, alone, would be the first to be blamed. This two-directional relationality — seeking the company of others for one’s own comfort as well as to provide comfort to others — principally underpins the character of Aboriginal relations in central Australia, or, what I call Warlpiri forms of intimacy.17

Through their structure (the ease with which they were erected and unproblematic availability of required materials), or the way of building in Heidegger’s sense, olden days camps accommodated for as well as generated mobility, intimacy and immediacy, the core values encapsulated in the concept of ngurra. Put differently, the particular structure of camps allowed for as well as generated particular forms of social practices (ways of dwelling, in Heidegger’s sense). In tandem, these structures and these social practices embodied and produced Warlpiri ways of being in and thinking about the world. The ways in which the structures, the social practices and the ways of being in the world interconnect and create meaning can be iconographically summarised and metaphorically expressed through a set of concentric circles and the concept ngurra.

The values underlying the concept ngurra (mobility, intimacy and immediacy) clash with the values the house is imbued with (stability, privacy and future-orientation). Accordingly, when Warlpiri social practices interact with state-provided houses the result is something different to what Australian governments envisioned in the process of sedentisation. Instead, contemporary life in the settlement of Yuendumu continues along some of these parameters, and adapts continually to the presence of houses and what they imply. Following Moore, these changes in contemporary Warlpiri ways of dwelling in camps and in houses need to be understood as situated in a web of new readings of new and old practices — rather than a Warlpiri inability to comply with a particular way of living in Western-style housing. Following Robben, Warlpiri and Kardiya styles of dwelling in houses are not dependent on the structures, the houses, but on the appropriation of meaning through social practice.