CHAPTER 3

Transforming jilimi

Sedentisation, the creation of the settlement of Yuendumu and the provision of housing engendered the intersection of the Warlpiri and the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking. This intersection, in turn, set in motion any number of social processes which are manifest in, for example, the ways in which Warlpiri people engage with Western-style houses. These processes are multidirectional and may alter over time; and they feed back into ways of being in the world. An example of this is the jilimi, or women’s camp. The social processes set in motion with the intersection of the two series of building–dwelling–thinking have substantially transformed jilimi from a gendered, spatially specified and single-purpose residential form into, as we will see, multipurpose, residentially complex and much larger domestic arrangements — often located in and around houses.

In the olden days, jilimi were temporary residential settings for the single purpose of mourning. Since sedentisation in 1946, Yapa social relations at Yuendumu have undergone significant transformations that are manifested in, among other things, the phenomenon of contemporary jilimi (see also Bell 1980a: 177, 1993: 139; Dussart 1992: 345; Hamilton 1981: 75–6; Peterson 1986: 139). Their original olden days purpose has been vastly extended and jilimi have increased in numbers and in size, and have also changed significantly in terms of residential composition and complexity. From a temporary residential arrangement for women during mourning they have been transformed into centres of sociality, not only for women but for children and men as well.1

Today, there is an ever-changing number of jilimi at Yuendumu, usually a handful or so of large ones and any number of smaller ones. In the 1980s, for example, according to Dussart (1992: 345), there were six principal jilimi at Yuendumu. A decade later, Keys (1999: Appendix 5: Locations of jilimi in Yuendumu) details a total of thirty-two jilimi locations between February and October 1995, seventeen of which were spatially independent and fifteen of which were attached to or surrounded by yupukarra (married people’s camps). During my research, the number of jilimi fluctuated significantly, with a minimum of six large and spatially independent ones and an ever-changing number of smaller ones at any one time. In contrast to Bell’s characterisation of jilimi in the 1970s at Alekarenge (previously Warrabri) (1980a, 1993), those at Yuendumu are not land- and ritual-based, nor do they provide a power base for women (see also Dussart 2000: 44). Yet today’s jilimi are focal points around which much of everyday life at Yuendumu revolves, and as such they are an excellent site to explore two aspects of the intersection of the Warlpiri and the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking at Yuendumu.

Firstly, I show how the transformation of jilimi from single-purpose mourning camps to large, numerous and socially complex contemporary camps needs to be understood in relation to changes that the institution of Warlpiri marriage has undergone in response to sedentisation and the resulting changes in circumstance. Jilimi in this regard are an example of how core concepts belonging to the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking are transforming.

Secondly, I introduce the actual jilimi that Nora, Joy, Polly, Celeste and I lived in, the one that was my home for over a year of fieldwork, and in which the ensuing case studies about mobility, immediacy and intimacy are set. This jilimi is located in and around a four-bedroom house, and I discuss how the four women relate to each other and the jilimi’s four rooms. This interplay between a contemporary jilimi and the structure of a Western-style four-bedroom house illuminates how the first process (the transformation of jilimi) in turn feeds back into the intersection of the two series of building–dwelling–thinking and creates particular dynamics, played out in Warlpiri practices of dwelling in Western-style houses.

Changes in marriage and the jilimi

In the olden days, ideally, girls grew up in their parents’ yupukarra, and at an early age (according to Meggitt 1962: 268–9, at eight or nine years) moved into a yupukarra with their (first and much older) husband. There they lived until widowed, when they spent the appropriate time for mourning in a jilimi, before remarrying and moving into yet another yupukarra with their next husband. With this ideal life cycle for women in pre-contact times, jilimi did not have a prominent position in everyday life, simply because women lived in yupukarra for most of their lives and stayed in jilimi rarely and only for the purpose of mourning.

The dramatic changes in prominence, number, size and purpose of contemporary jilimi result from changes in both residential practices (sedentisation) and the Warlpiri institution of marriage. What constitutes a marriage in Warlpiri eyes today? How has that changed from the past? And what do these changes mean in regard to the ways Warlpiri people live their lives today — and, specifically, how do these changes interact with Yapa ways of relating to domestic space?

In the olden days, marriages were living and economic arrangements between husband and wife, as much as they were (in a sense, contractual) arrangements between the husband and a woman’s matriline, especially her mother’s brothers. According to Meggitt, during the olden and the early days, there existed three ways for a man to legitimately acquire a wife, in the negotiations of all of which the matriline was instrumental. These three kinds of marriages came about ‘through the levirate, through private negotiation with the women’s kinsmen, and as a result of being circumcised by a man who becomes his father-in-law’ (1962: 264). The third type, arrangements made during initiation, where the circumciser promises an as yet unborn daughter to the circumcised, according to Meggitt, was the ‘ideal marriage arrangement, and indeed the most common’ (Meggitt 1962: 266).2

Today, the few remaining examples of the first type of marriage, the levirate (where a man ‘inherits’ the wife/wives of his deceased brother), exist in the oldest generation of Warlpiri people alive. I am not aware of a continuation of this practice by the younger generations.

The second type, where negotiations between families, particularly matrilines, result in the marriage of a young girl, has also apparently been discontinued. In regards to the third type, initiation rituals continue to take place at Yuendumu almost every year, and marriage promises continue to be made during them. However, for a number of reasons, which seem to be working in tandem, today these promises rarely eventuate in actual marriages.

The first of these reasons is that matrilines, formerly instrumental in putting marriages into effect, seem to have lost their power, as the absence of the other two ways of ‘legitimately acquiring a wife’, among other things, indicates (see also Peterson 1969 on the roles of matrilines in marriage arrangements, and Dussart 1992 for recent changes).

Secondly, while the age difference between ‘promised’ potential spouses remains substantial, in actual marriages this has shrunk significantly. During Meggitt’s research, the age difference between spouses at Yuendumu in their first marriage was on average twenty-one years (Meggitt 1965: 156); today it is less than five years amongst the youngest married generation. In the past, this age difference, in tandem with support of the girl’s matriline, must have made enforcement of marriage (should a girl have been unwilling) easier for the much older husband.

Thirdly, the economic motivation to enter a marriage has waned. During the olden days, men and women combined their subsistence forays, and nuclear (and extended) families were tight economic units with clearly gender-defined rights and responsibilities. Sedentisation under colonial rule and ensuing post-colonial welfare arrangements led to crucial shifts in forms of subsistence and thereby a shift in roles and responsibilities of spouses. Economically, marriages are not of any crucial significance any more: quite the opposite. Through Australian welfare arrangements, women especially benefit financially from not being married (see Dussart 1992).

Fourthly, with a significant weakening of the contractual aspects of a marriage as between matrilines, room opened for more individualistic reasons underlying the choice of a spouse, chief amongst them love. This has been further underscored by enhanced mobility, and by the growth of larger, concentrated populations, which has led to an enormously increased choice of potential marriage partners.

The general picture Meggitt presents of Warlpiri marriages at the time of his research is one of stormy durability. On the one hand, he declares, that ‘the Walbiri divorce-rate is much lower than that in a number of native societies’ (Meggitt 1962: 103) and asserts that ‘the norm of long-term unions is generally achieved’ (ibid.). On the other, he elaborates that ‘there is a high incidence of casual adultery’ (Meggitt 1962: 104), and his ethnography is testament to that, providing numerous detailed case studies revolving around disputes to do with adultery. After presenting a number of vignettes concerned with adultery, Meggitt states:

It is impossible in the circumstances to estimate accurately the incidence of adultery among the Walbiri. To judge from their remarks to my wife and myself and from observed situations, most of them probably commit adultery several times during early married life, while for a few it is a pastime to be pursued on all occasions (Meggitt 1962: 107).

In relation to what Meggitt calls ‘adultery’, nothing much has changed. What has changed drastically is the impact of infatuation, love and lust upon marriages. In the past, marriages usually seem to have withstood the turbulences caused by adultery; today often they do not. This does not seem to be due to a change in adultery, but to changes in the nature of marriage.3 That the stability of marriages has undergone substantial changes is illustrated in the following extract from my fieldnotes:

There are Thomas and Lillian, compared to many other Warlpiri marriages, theirs is a very close relationship, intimate, loving — sometimes. At other times it is real stormy, with lots of brooding, running away, and fighting. Netta’s husband dotes on her although, or because (?), she is more child than woman, continually sulking, very much dependent, and very very demanding. ‘You are a wife now’, they sometimes tell her when she is grouchy, ‘you have to behave yourself’. When Old Man’s younger wife left him for a younger man, he told Maisy (her sister and co-wife): ‘If I can’t have her, I don’t want you either’. Her sister was the one he loved. Now, Maisy says, she is divorced, but she lives with the old man, and looks after him. Viola’s husband got himself a second wife and her and Viola had big jealousy fights. When Rosalind came to Nyirrpi to visit, Viola asked if she could come with her back to Yuendumu — yes. Later her husband said: ‘I sent you to the shop, not to Yuendumu’, and she should return to him, but she didn’t want to. Did she have a boyfriend? Ih! [Emphatic no]. Years later and she quietly asks whether we are going to Laramba Sports (where her ex-husband will be, too) and she is always the first to jump into the car when we go to Nyirrpi (where he lives). Then there is Frederick and his two Glorias (one a wife, one a girlfriend) always fighting over him. Marsha who just ‘talked’ to Alex before they got married and their hours of quiet whispers every night; and how Walter burnt all his wife’s belongings because he was jealous.

These observations are similar to Meggitt’s vignettes about the tempestuous nature of Warlpiri marriages, but the crucial difference here is that two years after I wrote this, all of the marriages described had ended.

What has not dramatically changed, on the other hand, is the way in which a marriage is established. In the olden days, a marriage was simply announced by the woman joining her husband in his camp, forming a yupukarra:

When a man thinks his betrothed is old enough to leave her mother — that is, when she is about eight or nine years old — he privately asks her father and mother’s brother to send her to his shelter. The men instruct the girl’s mother accordingly, and the girl joins her husband without any formality. Her father and mother’s brother simply tell onlookers that the betrothal is consummated (Meggitt 1962: 268–9).

Significantly, especially in respect to contemporary practices at Yuendumu, Meggitt points out the following: 4

The statement that there is no wedding ceremony requires comment. The people regard the initial removal of the girl to her husband’s dwelling at his request as the termination of the betrothal and the beginning of marriage. Her walking through the camp to join the man constitutes the public statement of fact (Meggitt 1962: 269).

In similar fashion, a marriage today is announced by the public moving of bedding into a yupukarra. Indeed, the only way of finding out whether or not two people were married at Yuendumu during my research, if they were not already known to be married, was to hear that ‘X was now living in a yupukarra with Y’.5

Considering the ease with which a contemporary marriage is established, as well as the absence of power (or interest) of matrilines to enforce or prohibit a particular marriage, the absence of economic incentives to remain in a marriage, and the movement from contractual arrangement to individual choice, mean that today marriages can also be resolved more easily. In fact, aside from the emotional work required for most separations, the simple act of moving out of the yupukarra terminates a marriage.6

With the termination of a marriage, the former husband moves into a jangkayi and the former wife into a jilimi. Today, women live in the jilimi when they are in between marriages, or at any point in their life when they decide to remain single (this does not mean celibacy, as they may have one or more boyfriends, or run around from time to time). The increase in size, quantity and purpose of jilimi thus correlates directly to Warlpiri marriages being less stable today than they were in the past, meaning that women spend much less of their lives in yupukarra and much more in jilimi.7 Moreover, children, who now constitute a further substantial part of the jilimi population, have also changed their residential patterns as a result of these developments in the institution of marriage. If the ideal of a stable marriage is achieved, then children grow up living in their parents’ yupukarra.8 However, as the ideal case is rarely the norm today, children also often live in jilimi, sometimes with their mothers, or more regularly with their grandmothers, who take up a carer’s role.9 Men, as well, who rarely live (that is, sleep) in jilimi, may nonetheless spend much more time there during the day than ever before. Considering the storminess of contemporary marriages, many young and middle-aged men come to the jilimi to receive food and financial support from their mothers. Accordingly, the presence of men in contemporary jilimi, especially around mealtimes and during early evening socialising, is by no means unusual.

Our jilimi

The flux in numbers and locations of contemporary jilimi at Yuendumu already indicates their lack of stability over time. This flux needs to be understood not only in terms of location, but also in terms of residential composition. As women decide to stay single, and the marriages of others dissolve or are being formed, they and their (unmarried) children move in and out of jilimi (creating some of the flow of residents through jilimi discussed in the next chapter). The six more permanent jilimi at Yuendumu are no exception.

I first knew ours as a long-established jilimi in this location when I began research at Yuendumu in 1994. However, the women and children who were some of its core residents in 1999 (the period of the case studies) did not live there five years earlier, nor did they live there just a year or so later. While the same locale remained a jilimi until 2005, it is now a yupukarra.

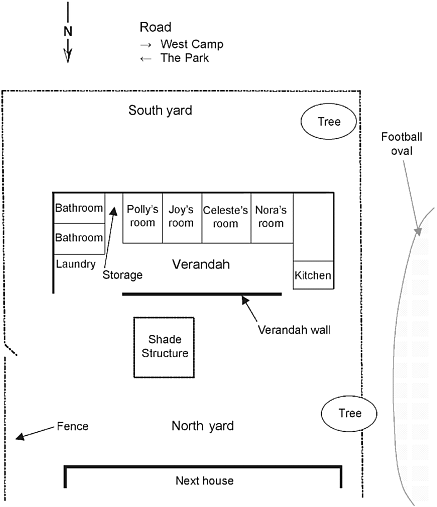

This jilimi is located in Yuendumu’s Inner West Camp, within easy walking distance of the Park. Its most immediate neighbouring camp is yet another jilimi, while all other houses in its vicinity are occupied by yupukarra, sometimes with smaller jilimi attached to them (and the house across the road from the jilimi is the one in which the Catholic nuns live, known as ‘Little Sisters’). The jilimi is situated in and around a house made of corrugated iron. This house has four identical-sized rooms (approximately 2.5 x 4 metres) adjacent to each other, which open onto a roofed verandah facing north (Figure 8). The verandah is separated from the yard by a wall about one metre high.

Figure 8: The jilimi — spatial layout

Each room has a louvred window to the south (always shut) and a door opening onto the veranda facing the north yard. At the western end of the structure is another (windowless) room, which opens onto the verandah without a door, and a (dysfunctional) kitchen. At the eastern end are a storage place, which can be locked, and two bathrooms with a shower, sink and toilet each, as well as a little laundry space with a tap and a washing machine. The house is located in the southern half of a yard. Nowadays, the yard is confined by a fence on three sides, about 25 metres long and 35 metres wide; and the back of an identical house on the northern side (the neighbouring jilimi). In the middle of the yard between the two houses is an iron structure which, when covered with canvas, provides shade and often has shelters and leafy branches for extra shade attached to it. To the north-west is a large tree providing further shade. The yard space south of the house is rarely used, mainly perhaps because it is not visible from the other spaces.10 It does not usually comprise part of the jilimi’s yarlu space. The yarlu space, in the main, is made up of the north yard and the verandah, where most of the social activity within the jilimi takes place. This is where in the evenings the yunta normally are arranged.

The vexed issue of room ownership

Not all jilimi are located in and around houses, but when they are, as ours was, then they face the same issues as all other camps which are located in houses. One of these issues revolves around the roles and functions of rooms. Conventional Western-style houses are normally divided into rooms with shared access (lounge, dining room, etc.) and private rooms (bedrooms). Bedrooms in Western-style houses are ‘meant’ to be used as private spaces; ideally, one room is allocated to one individual (or a couple). Practically, this is not feasible because of the ratio of people to bedrooms in Yapa-occupied houses (in 1999 the average was 4.5 persons per bedroom, see Musharbash 2001a: 6). Ideologically, this use is also not acceptable because of the preference for sleeping next to others (providing and receiving marlpa, company). Olden days camps had no rooms; each person had their spot in the yunta to sleep in and their yalka for storing personal belongings. There were no physical separators between these spaces; all could be seen and none differed from each other. How are bedrooms used, then?

Firstly, individuals hardly ever sleep in them alone (this is as rare as a one-person yunta). When rooms were used for sleeping, which happened in the jilimi only when it was very cold or rainy indeed, then a number of people slept in one room.11 The jilimi house’s four rooms were mainly used for storage, particularly (but not exclusively)for bedding during the day. This is a neat way of dealing with the contrast between permanence as a value underlying houses and mobility as a value underlying camps: While the house is there all the time, the yunta which create the camp are put up again each night (and during the day the bedding which creates the yunta is out of sight in the rooms).

However bedrooms are comparable in one way to those in Western-style houses, as not all jilimi residents have equal access to all four rooms. In fact each room is known to ‘belong’ to a particular woman at any one time. When I first moved into the jilimi in late November 1998, the jilimi’s four rooms were said to belong respectively to Polly, Joy, Celeste and Nora.

This is not a kind of exclusive ownership in terms of rights over the room’s space and use. It is more accurately described as an association between a room and a person. ‘Celeste’s room’ for example was the one in which she stored most of her belongings and where she slept when it was cold. However, she never spent any time alone in it. She shared access to and use of the room with the people who stayed with her in the jilimi, as well as some of her relatives who lived in other camps. They stored their belongings in it, sometimes slept in it, and generally entered it without asking Celeste for permission. Other jilimi residents, however, would neither use nor enter it. Ultimately, when Celeste moved to another camp, ‘her’ room became somebody else’s, and her association with it as well as her and her associates’ access to the room ceased entirely.

While each room is associated with at least one main person at any one time (and these associations shifted), ‘room ownership’ in no way impacts upon access to and control over any of the other spaces in the jilimi (as it would in a non-Indigenous-occupied house, where only those people who have bedrooms generally have some ‘say’ about the rest of the space of the house). Nor did ‘room ownership’ add any weight to a woman’s standing within the jilimi, i.e. no power was associated with this kind of ‘ownership’. Apart from the rooms, access to the rest of the space of the jilimi is equally distributed to all residents present at any one time. This is not to say that disagreements between residents do not take place, but whether or not a woman ‘has a room’ in these cases has no impact on arguments.

What ‘room ownership’ did do for women while they ‘held’ a room was associate them directly with the jilimi — which was considered by them and others as their home. However, room ownership is in no way a requirement for considering the jilimi one’s home. There are many people who lived in the jilimi and called it their home but who never ‘owned’ a room there. Neither was room ownership an exclusive symbol for social centrality in the jilimi; while Joy, Nora, Celeste and Polly were central to it, at least while they lived in the jilimi, so were a number of other people who did not own a room. To underscore the insignificance of room ownership in this regard, I know of at least one woman who, before Nora moved into her room, was said to ‘own’ this room while not actually living in the jilimi.

The issue of ‘room ownership’ alerts us to the fact that rooms can be ambiguous spaces. They are not easily and clearly related to persons; and their use throws up interesting issues in respect to the sociality of camps when set up in and around houses. Rather than following the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking and using bedrooms as spaces of privacy, Yapa seem pragmatic in their dealings with rooms, using them in such a way that it suits their purposes (which, of course, are built on the values underpinning the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking). Interesting in this context also is that the fifth room, the one on the western side without a door and with open access to and from the verandah, was at no stage said to ‘belong’ to any particular person, though in all other regards it was used in a similar fashion to the other rooms, i.e. for storage of bedding and sleeping in when rainy or cold, by a changing number of individuals. Since it had no door and no windows, however, it was never considered a ‘proper’ room. Nobody ever claimed it as theirs (even when using it over a period of months), nor was it ever verbally described as ‘someone’s’ room.

Lastly, while these four rooms were said to belong to Polly, Nora, Joy and Celeste for a while, the respective rooms belonged to other persons before they moved into this particular jilimi (all at different times) and after they left. This hints at the process of forming and maintaining jilimi. They are not randomly formed by women and children who at any one time choose to live in one; rather, when a woman decides to move into a jilimi, she generally moves into one where relatives live already. This slow process of acquiring and losing core residents is what happened to our jilimi too, and because it was one of the larger ones, sheltering many more core residents than other jilimi, this is perhaps the reason for its comparative durability.

Polly, Nora, Celeste and Joy

To underscore the relationships between core residents, let me here outline as an example how Polly, Nora, Celeste and Joy related to each other (and note that they all arrived at the jilimi at different times, and also moved out at different times, except for Polly and Celeste, who moved out of this jilimi and into another one together). These four women were not the only core residents during the time they lived in it; all except Polly brought with them children they were caring for, some brought sisters and aunties, and lastly, there were other women as central as them who called the jilimi home and who were not close relatives.

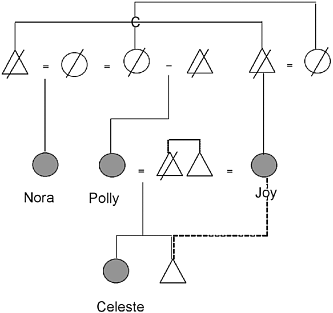

Both Polly and Nora were widows in their seventies. Celeste and Joy were in their early and mid-forties respectively. Celeste had left her husband many years before and had been single since; Joy also often lived in a camp close by (on the other side of the Little Sisters) with her divorced husband (divorced here meaning that sexual relations had ended though the relationship continued). These four women are related to each other in a variety of ways (Figure 9).

Polly, Nora and Joy are what at Yuendumu is called ‘close’ sisters (the term ‘close’ qualifies an otherwise also possibly classificatory kin relationship as substantiated through biological, adoptive or similar connections). Joy’s and Nora’s fathers were brothers. Joy’s and Polly’s mothers were sisters. Polly’s and Nora’s mothers were co-wives of the same man (Nora’s biological and Polly’s social father; Polly’s real father was a man her mother had an affair with). The bond between Polly and Joy was further reinforced through marriage and adoption links. They were married to two (close) brothers (Polly’s husband was deceased by the time I met her). Following a common Warlpiri practice, Polly, who had eight children of her own, had given one of her sons to her sister Joy, who had none. Joy thus adopted and brought up one of Polly’s sons, who passed away a number of years ago. Joy now looks after his children. These biological grandchildren of Polly’s consider Joy their first grandmother and stay with her rather than Polly when they spend time in the jilimi. Celeste is Polly’s daughter; and Nora and Joy are thus ‘close’ mothers of hers.

Figure 9: Polly, Joy, Celeste and Nora’s genealogy

These four women are connected by genealogical bonds, and share much of their life histories, as well as, during different periods of their lives, experiences of co-residency — thus drawing them together for the time that they all lived in the same jilimi. Let’s look at the jilimi, then, and examine how the values of mobility, immediacy, and intimacy are integral in shaping its everyday.