CHAPTER 7

Intimacy, mobility and immediacy during the day

At night, the jilimi (or any other camp) shelters its residents, those people who sleep there. Who sleeps in which camp and next to who, I previously declared, is related to social engagement during the day. Here, I present and analyse examples of such daytime social engagements of jilimi residents (and others), showing how these interactions cultivate — and are cultivated by — mobility, immediacy and intimacy.

The relationship of daytime activity and the restfulness of night has also been elaborated upon by Sansom in regard to the relationship between spatiality and sociality in Darwin fringe camps, about which he says:

Although there is a day and night contrast between the camp doing and reforming and the camp resting and formed, people in both the active and the resting state should locate themselves in places where they have reason and business to be. Unrolling a swag ‘one side’ and spending long day-time hours ‘other side’ are contrary allocations of time. They raise the issue: ‘Which way you bloody think you goin?’ (Sansom 1980: 111)

Correspondingly, my aim here is twofold. On the one hand, I follow jilimi residents (and others) through the day (and often, away from their camps). On the other hand, I am interested in the mutations the jilimi undergoes during the day through the contractions and expansions in terms of presence of people in it.

I analyse the daytime spatial and social restructuring of the jilimi by drawing on Munro and Madigan’s (1999) concept of time zoning, developed to analyse spatial uses of domestic space during different times of the day. Based on research in Scottish suburban homes, they transcend the truism that the inside of a house is private and the outside public, proposing that private/public distinctions operate inside the house as well and are not only spatially defined but also, and importantly, temporally. They argue that the spatial division in Western houses into shared rooms (such as living rooms and bathrooms) with greater public access and private rooms (such as bedrooms and study) can be further extended temporally. Different people use these spaces, especially the shared ones, differently at different times. The living room, for example, after being the realm of the ‘housewife’ for the early part of the day, may be taken over by children and teenagers in the late afternoon, then the entire family, and later in the evening by husband and wife and perhaps guests. Time-zoning in the sense of Munro and Madigan (1999) is the negotiation of relationships inside the private domain of the home by allocating space temporally to different persons and for different purposes. I find, with certain caveats (e.g. different definitions of privacy are at work in the Scottish and the Warlpiri contexts), the concept of time zoning works well transposed to Warlpiri camps.1 A camp is a different place at different times of the day (or night) because different people congregate and perform different activities within it.

I pursue these issues by first outlining the daily cycle of an ordinary day from a camp-centric perspective, and then present ethnographic examples of breakfasts, of mobility during the course of the day, concluding, as the day does, in the late afternoon back in the jilimi, with a discussion of negotiations about firewood.

The daily cycle

The daily cycle as described here is an ideal representation. Normally, of course, the everyday is interrupted by any number of occurrences and events, from fights to mortuary rituals, Sports Weekends, initiation ceremonies and so forth.2 On a normal day without exceptional events or interruptions, then, as the sun comes up (mungalyurru-rla), the camp slowly comes to life. The rustling of senior women starting the cooking fires announces the beginning of the day. As the women prepare tea and damper, the remaining sleepers get up in their own time and congregate around the cooking fires.3

Sitting in groups around the fire in the morning is a social activity much cherished, both for the warmth provided by the fire and for its sociality. This is the time when the first visitors from other camps might come over to share breakfast (or people leave the camp to do so themselves elsewhere). Breakfast is a sociable time, with people eating, chatting, and discussing their nightly dreams or their plans for the day. Once breakfast is finished the cooking fires are allowed to burn down, unless it is cold, in which case they are turned into warmth fires for those residents remaining in the camp. Bedding is put away, and residents with a job, a hunting trip planned or any other task at hand leave the camp. Usually only the old and infirm and young children remain in the camp, with a few people to look after them and keep them marlpa (company). They pass the time chatting, playing cards, working on acrylic paintings, making carvings and so on. Older children go to school, play in the camp or may go to find friends to play with — and often take off not to be seen again until dinnertime.

Around lunchtime (kala-rla) the camp fills up again. Many eat lunch away from the camp at work, or at the shop’s Take Away. For those who come home to the camp, lunch is a more individual and briefer affair than either breakfast or dinner, and not highly structured. Sometimes a large pot of soup is made, from which everybody who comes to the camp for lunch serves him or herself. After lunch, some people return to their jobs, or go hunting or for a drive or walk around the settlement to see what is going on, and the remaining people stay in the camp. Especially in summer when it is overpoweringly hot, a camp after lunchtime is made up of groups of people congregating on blankets in any available shaded place, dozing, reading magazines, de-lousing each other, discussing what happened earlier in the day and gossiping.

As the afternoon (wuraji) wears on, many people who had been elsewhere return to the camp, and others from other camps may come visiting. By now there will be large groups of people sitting on blankets, socialising; this is also the time to start getting firewood. As it gets dark, most visitors leave the camp they are visiting for their own camps, and the cooking fires are started again. Dinner is a more intimate affair of people gathering around ‘their’ cooking fires in small groups, sharing food and company. A large billy of tea is cooked on each and shared by the group of people using that particular fire. Individual women around one fire put meat they each bought (or received as gifts) on the fire and then share it with those they are looking after.4

After sunset (wuraji-wuraji) and following dinner, there is again an intense period of visiting: people coming and going to visit from camp to camp for story time. Story time means sitting around a fire with close friends and relatives and exchanging news and gossip, remembering events from the past, planning trips, and joking. If there are groups of senior women present, story time often turns into singing of jukurrpa (Dreaming) songs and telling olden days or early days stories.

At night-time (munga-ngka), swags and bedding are brought out and put into yunta, and people start retiring onto their mattresses, while continuing conversations started during story time, or watching television (television sets are often brought out at night and put up in front of a yunta; alternatively, people watch inside the house and then come outside to sleep). One by one people fall sleep when they get tired, disturbed by nothing but the occasional need to push a log further into a warmth fire, and maybe a pack of dogs howling now and again (unless there are disturbances such as fights or drunks coming home late and making a racket).

In a 24-hour period a camp experiences quiet times, such as at night when people are asleep and in the mornings after most residents have left after breakfast. Other times are intensely social, such as breakfast, late afternoons and story time. Others again are distinguished by their intimacy, like dinnertime.5 These ‘moods’ are dependent on who is present, how these people are distributed across the yarlu of the camp, and, of course, the types of activities they are engaged in.

Breakfast and the importance of damper

Depending upon weather, the availability of firewood, and the availability of food, breakfast is cooked and eaten outside. Typically, the morning in the jilimi begins by some of the older, but not the very old women, starting cooking fires to boil the billy for tea and for the hot water required for making dough for damper.6 This signals the first step from resting to being active. It is during breakfast that an initial camp-internal reshuffling of sociality occurs, when the spatiality of sleeping arrangements in yunta reforms into the spatiality of seating arrangements around the breakfast fires. Significantly, visitors start to arrive in the camps around breakfast-time. They may only spend a few minutes in the jilimi, e.g. a man picking up damper from a mother or grandmother, or the whole day, e.g. an old lady coming to visit a resident old lady to pass the day with her.

There may be one breakfast fire to each yunta; however this is unusual. More frequently only one or two fires are lit. Fires are located a little distance from the yunta, so as not to wake up the sleepers with the clatter and the smoke. By and by, as the other sleepers wake up, they gather around the breakfast fires according to their closeness and the state of relations to the damper-making women. Seating arrangements around breakfast fires could be mapped in a parallel way to sleeping arrangements in yunta. In retrospect, I wish I had taken regular maps of the number and locations of breakfast fires, and especially of seating arrangements around these fires. But breakfast-time was when I wrote up my fieldnotes. It was the only time I was able to write without being interrupted, and accordingly I scribbled madly while drinking my tea and eating damper, without time to note too closely what was going on around me. As soon as I put the pen down ‘the day started proper’ and I was too busy for further note-taking, and breakfast was over in any case. I therefore cannot produce any such maps, only some general statements about breakfast fires and seating arrangements that such maps would have provided and underscored.

Unless relations between yunta are really bad, there are fewer breakfast fires than there are yunta. The reordering of people from a number of yunta where they slept to a smaller number of breakfast fires where they eat points towards a beginning of an increase in the volume of sociality. The state of restfulness of the night is lifted by opening up the more intimate formations of yunta. Breakfast fires invite people to begin the day through increasing contact with more people.

Which fire to choose and where to sit depends on similar issues to — and is conducted in an equally non-verbal manner as — the nightly establishment of yunta. Invitations are not issued. People get up from their yunta and walk over to a fire of their choice. This choice depends upon who else is sitting there, who one would like to sit next to or not sit next to, how much room there is around individual fires, which way the wind and smoke are blowing, and similar issues.

Sometimes (especially after the redistribution of flour after ritual, discussed below), there may be a number of breakfast fires in the jilimi, on all of which tea is cooked, and around each of which people sit and eat their breakfast, but only one fire for the production of damper. In this case, people eating breakfast at one of the other fires get up, get their damper from the damper-making woman, and return to share and eat it at their fire. Other food items such as butter or jam are generally shared by the people around one fire, and if relations between different fires are good, may also be passed from one fire to the next. People from neighbouring camps may also come over to ask for some butter, jam, sugar or salt.7 Closely related people residing in another part of Yuendumu may drive over to request one of these items if they need them and know that they are available in the jilimi.8

The fire one chooses to sit at is the fire where one eats. Parallel to the way one sleeps in only one yunta, one eats at only one fire. A major difference to yunta is that breakfast fires may be joined by people from other camps, especially by younger people coming to receive their share of their older (always female) relatives’ food. Others who come to pick up damper from a breakfast fire to take over to their own camp may briefly join in; however they usually eat elsewhere.

The mood around a breakfast fire depends upon a number of issues. If relations are good, or there is enough firewood available for a number of breakfast fires, breakfast can (and usually is) a sociable yet homely affair. If relations between yunta are uneasy and a shortage of firewood forces people to share a breakfast fire despite their personal inclinations, then people tend to cut breakfast-time short. Lastly, as happens frequently, particularly towards the end of the fortnightly pay period, there may not be any food in the jilimi, and in this case only tea is boiled and quickly drunk, and then the fires are left.

Flour, damper, and gender

Damper is not the only food eaten at breakfast, and neither is it eaten every day. Other breakfast foods include porridge or weetbix, often toast, tinned meat or jam, and fresh meat. Damper however was the most common breakfast staple during my fieldwork, and as such it provides valuable insights into the dynamics of breakfasts and how they relate to sociality at Yuendumu. Whether or not damper is made in the mornings in the main depends on the availability of firewood and flour. Here I look at flour, at who is involved in the production of damper, and how it gets distributed. While my description mainly arises from observations made in the jilimi it needs to be mentioned that many yupukarra also are places of damper production. These are yupukarra with senior women resident in them. Younger women tend either to buy bread or to get damper for themselves and their charges from their mothers or grandmothers. Damper production is not only age-graded but also gendered in that it is exclusively women who make damper; I have never seen a man make damper.9

While all women know how to make damper, only a few do so regularly. In the main, they are senior women who look after others. The people they look after with damper comprise children and grandchildren, particularly male ones, husbands if they have any, and often also older female relatives. The latter usually ‘pay’ for their services with flour. For example Pearl and Bertha, Nora’s older sisters, always bought 20-kilogram buckets of flour as soon as their pension cheques arrived, but never made damper themselves. They usually passed the flour, and with it the damper-making responsibilities, to either Nora or Polly. The woman who received their flour in return made damper for them, for herself, and for her charges out of it. Not only do the old woman ‘pay’ for the labour involved with more flour than they receive back in damper form, but the damper-producing women factor the receipt of such flour into their budgeting.

Polly was regularly the first person in the jilimi to start a breakfast fire, for several reasons. She always woke up early, and making damper gave her something to do, but more importantly she saw it as her responsibility to produce damper for the many people she knew depended upon her. In fact, we all came to rely on Polly so much so that one entry in my notebooks reads: ‘Great confusion this morning, Polly didn’t make a fire, and no-one in the jilimi has damper or tea’. Her damper-making responsibilities encompassed not only older sisters staying in the jilimi¸ but usually also Celeste and myself, and any number of her grandchildren staying with her or with Celeste. Many of her descendants would come to the jilimi in the mornings to pick up ‘their’ damper. In Polly’s case, grandsons living in jangkayi, men’s camps, regularly came for damper in the mornings; in Nora’s case her sons would often do the same.

The seniority of the damper-making woman and her role in nurturing those dependent on her (both younger, e.g. children and grandchildren, and older, e.g. older sisters, and sometimes husbands) can be illustrated by Polly’s and Celeste’s co-operation in these matters. Normally, Celeste and her direct charges were encompassed in the much larger number of people Polly catered for, with Polly and Celeste pooling their flour and Polly normally being in charge of production. Thus, when Joy initially asked Celeste to help her look after me, including my breakfast provisions, Celeste often did not make the damper herself, but got it for me from Polly.10 However, when Polly was absent, Celeste took over her role and produced damper for her own as well as for Polly’s charges. Although I cannot be absolutely certain, to the best of my knowledge I cannot remember Polly and Celeste ever making damper at the same time. Other senior women in the jilimi at times also pooled flour and responsibilities with Polly, and at other times they did not, depending upon relations between them. For example, Polly sometimes made damper with Joy’s flour for Joy and her charges. More often, however, both women made damper at the same time, on different fires.

The gendered nature of damper production is expressed not only through the non-existence of male-produced damper, but through distribution and production itself. Individual men receive their daily morning damper ration from their wives, mothers or grandmothers. In the case of some large ceremonies, the gendered nature of damper production and distribution becomes even clearer. During these ceremonies, men and women camp on separate sides of the ceremonial ground (men to the east, women to the west). Just after dawn, the beginning of the day is signalled by a number of women walking to the middle of the ceremonial ground to hand over a large amount of damper to a few men who carry the damper to their side for breakfast. Significantly, all women present are required to rise when the fires are lit before dawn, either to participate in or at least be witness to this damper production, underscoring the link between women and damper.

At Yuendumu, there are two ‘kinds’ of flour: privately bought and owned flour and flour received after ritual. Women who make damper try to ensure in their budgeting that they have enough flour for the fortnight between one pay or pension cheque and the next. The damper produced from this flour is theirs to eat and distribute. The ‘other’ flour arrives in the jilimi (and other camps where senior women reside) as a result of distributions undertaken during ritual, most often mortuary rituals. Mortuary rituals end with a distribution of large quantities of blankets, flour, tea and sugar to the mother’s brothers of the deceased. This second ‘kind’ of flour undergoes a number of significant transformations and exchanges before it gets consumed in damper form (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Flour distribution during mortuary rituals

In mortuary rituals, ideally, the siblings of the deceased pool their resources to sponsor the goods, including flour, to be distributed to the deceased’s mother’s brothers at the end of the ritual. The siblings are in turn supported by their close relatives, and today by grants for these purposes. Yuendumu Big Shop (which is set up as a Social Club, aiming to redistribute profits) often also ‘donates’ large quantities of flour (and tea, sugar and blankets) for mortuary rituals.11 During the course of the ritual, which may take anything from a few days to two weeks, increasing amounts of goods are stored in the sorry camp where the key mourners sleep and live. These goods are said to have originated exclusively from the siblings, but with their storage in the sorry camps they become a ‘public good’ in the context of the ritual. At the end of the ritual this ‘public good’ is redistributed to the deceased’s mother’s brothers and thus transformed into ‘private goods’. While the deceased’s mother’s brothers may keep items such as blankets and previous belongings of the deceased (which are part of the distributed goods) for themselves, they pass the flour on to their mothers.

‘Private’ flour turns into ‘public’ flour once the deceased’s siblings bring it to the sorry camps; it turns ‘private’ again when the deceased’s mother’s brothers receive it. Once the mother’s brothers pass it on to their own mothers, this flour not only becomes transformed into damper, but also into a good with a different redistribution status. The damper the mothers (of the deceased’s mother’s brothers) produce from this flour, in turn, is more public than damper made from privately owned flour, and less public than the damper distributed in central gendered ritual distributions described above. Firstly, it is passed on to all the residents in the jilimi, and to the sons who had passed on the flour in the first place. They come to the jilimi every morning to receive damper for themselves and residents of their respective camps while the flour lasts. Neighbouring camp residents may also come over and ask for a damper or two, if their senior female residents did not receive flour from the ritual. This goes on every morning for as long as the flour lasts (as this kind of flour often comes in numbers of 20-kilogram buckets, it may last for a week or two).

It is after mortuary rituals and other ceremonies involving the distribution of items such as flour that the above described central damper production takes place in the jilimi (and other camps), where all damper is produced on one fire and eaten around many. One woman is responsible for turning this flour into damper, and the damper rather than the flour will thus be further redistributed. Damper made from this flour is not public in the sense that it passes to all and sundry, but its distribution is more extensive, and crosses more camp boundaries, than that of damper made from privately owned flour. Once this flour is gone women fall back on their own flour, and distribution of damper made from this is much more limited.

Breakfast at Napperby

To further illustrate the significance of damper production, I describe a breakfast we made and ate at Napperby (also called Laramba), a mainly Anmatyerre settlement about 100 kilometres east of Yuendumu. Polly, who has part Anmatyerre heritage herself, and many of her close descendants, try and go to the Laramba Sports Weekend every year, as they have many relatives there. I went with Polly, Celeste and some of their close relatives to Laramba Sports Weekend in late August 2000, and we camped in the creek, just near the entrance of the settlement.

Napperby Creek is a magnificent camping spot, wide enough to allow for the comfortable putting up of many yunta, with large ghost gums providing shade. All people who came ‘for Sports’ from Yuendumu camped in the creek, and we took up a position at the northern end, furthest away from the road that crosses the creek into the settlement. Our camp was made up of a number of yunta, all sheltering close descendants of Polly. Polly herself, in a yunta with Neil and Amy, was in the middle of our camp. North of hers was a yunta with Gladys, her close sister, and Gladys’s daughter Sandra, and Sandra’s son Pete. North-east of them were Polly’s daughter Marion and her husband. South of Polly was a yunta with Celeste, her ‘son’ Brian, and myself. South-east of us slept Gladys’s other daughter Kate in a yunta with Polly’s granddaughter Camilla, her husband, and their daughters Angelina and Jemima, and south of them was Celeste’s adopted daughter Tamsin and her husband.

In the morning, we congregated around one breakfast fire and were joined by more of Polly’s relatives: two of her grown-up grandsons and their children, and a son of Gladys’s, his wife and child. Polly sat in the middle, surrounded by her relatives, next to the fire and positively turned into a damper-producing machine. The breakfast party quickly transformed into a carnivalesque scene with everyone shouting for more damper, the jam, some tin-of-meat; demanding spaghetti, the knife, tea, sugar; passing salt one way and meat the other; becoming louder and louder, everybody talking over everybody else and, most memorably, lots and lots of laughter. At some point, Camilla said to me, ‘Oh, I am happy. All the family together. This is good!’

I found that this breakfast was a celebration of relatedness. The sharing of food and the space around the breakfast fire, being grouped around Polly who churned out the damper, created a euphoric feeling of togetherness. Polly was central to this in a number of ways. Literally, she sat in the middle, next to the fire. She was also the common link through which all persons present could trace their relationships. And while everybody contributed to the breakfast with additional items such as tinned meat and jam, the staple, damper, came from her. The celebratory mood this breakfast projected was due to it being an anomaly. Not only was there an abundance of food (very unusual), enough for everybody to truly fill themselves, but there was an abundance of closely related people who did not usually share their breakfast with each other. In fact, with slightly varying compositions, the only other times I experienced breakfasts similar to this one were at other Sport Weekends, which is when relatives living afar meet in great numbers.

Polly’s centrality as a damper-producing woman, and, in this case, her role of ‘matriarch’, is what bound people together. Goodale (1996) has described the role of senior wives and female heads of households, so-called taramaguti, in the Tiwi Islands.12 There men tried to acquire large numbers of wives, resulting in establishments comprised of up to one hundred individuals, and taramaguti acquired the role of matriarch by becoming the matrifocal heads to these large establishments. The term matriarch sits somewhat uneasily with Warlpiri ethnography, as polygamy rarely exceeds two wives, neither of which would be distinguished from the other as first wife with more power in any case. However, the fact that the age discrepancy between husband and wife (or wives) used to be rather substantial meant that women usually survived their (first) husbands, and as they aged they turned into central figures for their descendants. In the main, this does not provide them with any ‘power’ but rather with a great number of responsibilities, such as looking after people, of which damper production is a central expression.

It is senior women in these positions who usually are the ‘damper-producing’ ones. And the damper they produce moves along their lines of descent. Elsewhere (Musharbash 2004) I have compared women in different age groups in respect to the food they distribute and are identified with, suggesting that the oldest ones alive are associated with bush foods, the older generation with damper, and younger women more often with ‘new food’, such as store-bought bread, salads, and stove-cooked meals. Damper, it needs to be remembered, is an introduced food item, closely associated with colonisation (see also Rowse 1998), and next to meat currently (still) the main staple in people’s diet at Yuendumu. The contemporary damper production going on in jilimi almost daily (provided flour is available) is a reminder of the centrality of these senior women, and what they stand for.13 Women in the jilimi make damper to feed themselves and their co-residents, and to provide sustenance to those they are close to, starting the day by inviting the network of people across camp boundaries based on descent. The day begins with children and grandchildren dropping in to pick up ‘their’ damper. Breakfast can be seen as a launching pad into the gradually intensifying sociality of the day, and damper as having a central role in this, as it travels along the lines of connections between people before it is consumed.

Daytime mobility throughout the settlement

If breakfast is the opening up or loosening of the restfulness of the night and the positions established there, then the end of breakfast signals the beginning of the ‘day proper’. From now until the yunta are put up again in the evening there is a steady increase in interaction with others. Naturally, this takes many forms and shapes. After breakfast, those who have a job leave for their offices, classrooms, or workshops. Children too young or not going to school (that day) form gangs and play in the vicinity of their camp, or, if older, also at quite considerable distances. The old and more immobile women in the jilimi start doing some craftwork or similar activity if they are up to it, or play cards, and receive the first of the day’s long flow of visitors. Those that do not have a specific task at hand usually do one of two things: go hunting (if transport is available) or go cruising (i.e. driving or walking around the settlement, checking out what is going on elsewhere, and visiting).

As I have already said, of the more than 1000 kilometres I drove each week, a lot was done close to Yuendumu (getting firewood, going hunting or swimming) and most of it in Yuendumu itself. Indeed, I spent many more hours driving around Yuendumu, than from Yuendumu to some other place. A lot of that driving was taken up by what is called cruising, and much of the rest by driving around before leaving Yuendumu for some other destination, or, what I call ‘hithering and thithering’. I examine these practices with a view to how they foster the ways in which people socialise with others and how they shape, create and reaffirm webs of relations.

Cruising I

When a person has no particular task at hand, the thing to do is to go cruising. At Yuendumu the usage of the term cruising is largely limited to describing the activity while driving around in a car. There is no specific word to designate the same activity performed on foot, and I use cruising to describe both.14 Cruising is more exhilarating and more fun in a car, but since cars are not always readily available, it is more regularly performed on foot. Cruising entails leaving the home camp and heading towards one’s usual stops: camps of close relatives, the shop, or the locations of specific organisations and institutions where one knows or expects to find people to talk to and hang out with. From the first stop one is propelled on to the next depending on who is there, what kind of news and gossip are exchanged and what is going on at the time. This is repeated at the next stop. To give an example:

In the morning after breakfast, Lydia, who did not have anything planned for that day, decided to start the day by walking over to Warlpiri Media. There she was hoping to find Delilah, who works as a radio announcer. Delilah indeed was there, and Lydia watched and helped her work, listening to music and answering some phone requests. Other people dropped by, and someone mentioned that Lydia’s cousin Megan had arrived back in Yuendumu from Alice Springs late last night. Lydia decided to walk over to their place and see what they had brought with them. At Megan’s place she marvelled at the new pram they had bought and sat down for a chat and for news about relatives in Alice Springs.

After a while, she and Megan decided to walk over to Megan’s sister Charity, who they knew would be ‘happy for company’ and who had not yet seen the new pram either. Lydia, Megan and her daughter walked over to Charity’s, where they sat down and exchanged and discussed their news. Then they, with Charity and her daughter, walked to the shop to buy drinks. At the shop they were exchanging Alice Springs news with some people there, when all heard yelling and shouting coming from in front of the council office, where a fight had broken out. Everybody ran over to watch. As the fight died down, Megan and Charity with their daughters decided to go and visit their sister Kiara, and Lydia went back to the shop in the hope of finding her mother there.

The best metaphor to describe cruising from a personal perspective is a pinball game (albeit with a ball that has its own mind): when cruising, one is being propelled from one place to the next by a conglomerate of reasons, moving from one point of the settlement to the next, carried forward on the impulse of news and gossip, and intercepted in one’s path by others. For example Lydia, Charity, Megan and their daughters each followed their own paths of cruising: overlapping and running parallel for a while, then diverting and splitting, while simultaneously each of their paths were crisscrossed again and again by other people in the same pursuit. Unless big events, such as fights, draw the paths of many people cruising at the same time to the one place/event, each cruising individual follows their own trail. This is determined by his or her inclinations that day, through their personal networks, and their objectives. Often paths overlap, or run parallel for a while (as did Lydia’s and Megan’s and then Lydia’s, Megan’s and Charity’s) but over the span of a day each of the three women’s cruising paths would have been individual and idiosyncratic. Cruising at the level of the person is a spatial expression of personal networks and one’s reaction to ‘what is going on’; on a general level it is an activity connecting people over the course of the day. Looking at it from a perspective of the dissemination of news and gossip, it must be said that cruising is part of why the mythologised ‘bush telegraph’ works so well. Any piece of news is distributed all over Yuendumu with enormous speed as it radiates out from its point of origin along the intersecting cruising paths of individuals. It is through cruising and related practices that it can be guaranteed that any important information is known all over the settlement within minutes, which, in terms of intimacy, also means that it is hard to keep a secret in Yuendumu and everybody knows everybody else’s business.

Cruising II

From a personal perspective, the trajectories of cruising take an individual from place to place in their personal fashion. From a spatial perspective, the practice of cruising means that people’s trajectories cross and overlap in some places more than in others, making them points of convergence for a great number of individual cruising paths. At Yuendumu, the Big Shop is such a place of intensified sociality due to overlapping cruising trajectories. Since most people shop for each meal, there already is much coming and going at Big Shop. People also go there to cash in cheques they have received, to spend money they have been given, to ask people there for money, and quite simply to see who else is there already. Another such main centre is the front of the Council building on mail days, especially on paydays. People go there to pick up their cheques, and other people go to receive (demand share) money from those who received cheques. Others go because many people are there already, and it is a good place to ‘hang out’ for a while and catch up on news. Other places where trajectories meet in a concentrated manner at various times are the buildings where Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Association is housed, Warlpiri Media, the Women’s Centre, and around ‘smoko’ the front of the school. And, some camps equally become the focus of many individuals’ trajectories, the jilimi chief amongst them.

The jilimi I lived in was empty only under rare circumstances (when a death occurred in the jilimi or when, very unusually, all residents went away from Yuendumu at the same time). Many of the older women resident in the jilimi stayed there during most of the day, attracting older women from other camps to come and stay with them, marlpa-ku (for company), so that both the resident old women and the visiting old women had company. These aggregations of old women in turn attract younger women, who come past to chitchat with their mothers, aunties or grandmothers for a while, which in turn attracts more young women and children.

Paydays always meant that card games were played throughout Yuendumu.15 These games in turn attract more people to come, either as spectators or as participants, and turn into ‘gambling schools’ easily encompassing more than thirty people or so. The jilimi regularly hosted ‘gambling schools’, causing frequent tension. On the one hand, residents were happy about the diversion, participating themselves in the gambling, and enjoying watching the games when the stakes were getting high. On the other hand, after each such event complaints mounted as the camp became ‘dirty’ with so many people being hosted, who ‘just leave their rubbish’ and ‘use toilet all the time’. Moreover, these gambling schools often continued all through the day and late into the night, hindering the jilimi residents from getting any sleep. One woman or another would turn the main electricity switch off and declare that the power meter, which in Yuendumu needs to be fed by ‘power cards’ was empty — but the gamblers always saw through the trick. Getting up in the morning after a night of no sleep, with no money left and in a camp littered with soft drink cans and chips packets, caused jilimi residents on a fortnightly basis to declare ‘no more cards in this jilimi’. But, with most of them being gamblers themselves all this was forgotten the next time cruising patterns caused the jilimi to be the locus of big gambling schools.

Hithering and thithering

Before going on a trip, no matter whether a hunting trip for a few hours or a trip to a place 500 kilometres away for a week, the car(s) to take the travellers drive(s) around Yuendumu, from one camp to the shop, to another camp, back to the first one, and so on usually for at least half an hour, often much longer. Although every anthropologist I know who has worked in central Australia is aware of this practice, and often impatient with it, I could find neither a name for it nor any anthropological discussions of it. In my notebooks I called this practice ‘hithering & thithering’, which I abbreviated in entries to ‘h&t’, so that there are daily entries such as ‘2 hours of h&t before we got out’.

‘H&t’ used to drive me crazy. I failed to understand its internal reasoning and its purpose, interpreting it instead as ‘disorganised’ behaviour. All that is needed for a hunting trip, I thought, is a car, people, crowbars, water, and some food (just in case). Considering that logistically this should be quite easy to organise, initially I used to despair about the amount of time it took from having the first person hop into the car to finally being out on the road. It took me a while to get used to ‘h&t’, and even longer to fully comprehend its meanings. Largely, this impatience was due to me, as the driver, having a different idea about the purpose of driving to that of the passengers. Focussing on the destination of the trip, ‘h&t’ became a chore, something that invariably and inevitably happened before we ‘hit the road’. While driving around Yuendumu impatient for getting to where we were heading, I did not at first realise that ‘h&t’ was as much part of the trip as was driving from Yuendumu to X. The first time I realised this, significantly, was when I was a passenger myself in a car driven by another Kardiya person in preparation for a trip to a site west of Yuendumu. All of a sudden, I was the one giving instructions as to which camp we needed to drive to next, that another stop at the shop had become necessary, and so forth. After this, I began paying more attention to ‘h&t’, and started seeing it as an end in itself, not only as part of the exasperating preliminaries to a trip.

Any kind of trip away from Yuendumu requires ‘h&t’. I focus here on hunting trips, but the general points are true independently of destination and purpose. A hunting trip often is ‘planned’ in advance by people suggesting ‘we might go hunting, might be tomorrow?’ hoping that something will develop out of it. Planning to go hunting first of all poses the problem of where to go hunting. Even if the initial suggestion is ‘we might go hunting at Wayililinypa, full up with yam’,16 this needs to be confirmed, okayed, and verified. Povinelli (1993) has described the ‘language of indeterminacy’ that permeates the decision-making of Belyuen women as they ‘decide’ where to go hunting and what for. She notes that an ‘important dimension to the sociality of hunting is the relationship among knowledge claims, responsibility – culpability, and authority – status’ (1993: 685), drawing out the fields underlying women’s hesitancy in determining the cause of action. The situation at Yuendumu is identical. The decision of where to hunt is not one easily made and partly underlies the ‘hithering and thithering’ illustrated in the following case study.

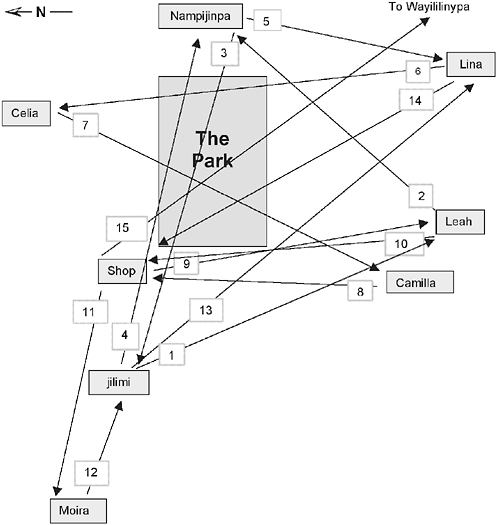

Yams were in season at Wayililinypa and Leah from South Camp had suggested to me a few days earlier that we could go hunting ‘might be anytime’, i.e. when it suited. A few days later in the jilimi during breakfast, I recalled her invitation and announced my plan to take her up on it that day. Polly and Celeste asked if they could come along marlpa-ku (for company). ‘Sure’, I said, and they and Neil hopped into the Toyota. The four of us drove over to South Camp to pick up Leah. She suggested that we also take her daughter Rita, her sister Eva, and her young grandson Marcel. From Leah’s camp, now eight of us in the car, we drove over to East Camp, to the camp where a number of Nampijinpa women at that time lived. Wayililinypa is their country and we wanted to let them know that we were going there. Most of them had already left to go hunting themselves earlier that day, but Lina and Delilah Nampijinpa had not got a lift and were keen on going too. Polly said in that case she would stay behind so there would be enough room for them. We drove back from East Camp to the jilimi in Inner West Camp to drop off Polly and then returned to East Camp to pick up Lina; Delilah had already gone to her camp to pack. Lina’s crowbar was at her husband’s camp in South Camp, so we drove there from East Camp to pick it up, and then on to North Camp to fetch Delilah and two of her little granddaughters. While at Delilah’s camp in North Camp, Neil chatted to one of the boys there and heard that Camilla had bought a new video, so he asked to be dropped off at her place in East Camp where they were watching it (also, the car by now was not only full to the brim, but full with women. Neil chose a polite way of opting out of the trip). After dropping him off in East Camp, we went to the shop so everybody could buy drinks and oranges, and ran into Moira who asked whether she could come along.

There were now ten people in the car (some of them large women), and some discussion ensued about what to do. Moira’s hunting skills are legendary and she would be fun to take along, so it was decided that Eva, who ‘is cripple anyway’, might as well stay behind. We drove back to South Camp to drop off Eva, back to the shop to pick up Moira and then to West Camp where she was living to pick up her crowbar. On the way back we stopped at our jilimi in Inner West Camp to get our own crowbars and the big jerry can for water, only to discover that somebody had borrowed it. Lina said she had one in South Camp so we went there and got her jerry can, returned to the shop to fill up with diesel and then were on our way to Wayililinypa.

Figure 16 shows the paths we took during this ‘h&t’ for a short hunting trip mapped onto a mud map of Yuendumu. Drawing a map of the paths a car follows during the ‘h&t’ before any one (hunting) trip, one inevitably comes up with something similar to this, namely, a representation of a finely spun web connecting a number of camps and other places distributed over several of Yuendumu’s Camps, and often spanning over the whole geography of the settlement. The Oxford English Dictionary translates the expression ‘to hither and thither’ as ‘to go to and fro; to move about in various directions’. And rather than disorganisation being the root of this practice, it is the purposeful moving about in various directions, the tying of connections, that underlies it.

Figure 16: ‘Hithering and thithering’

The actual paths taken and the connections created through them are important, as is the activity that takes place at each stop. Usually a stop, for example, at a camp so crowbars can be picked up, involves intense discursive activity between the people in the car and the people in the camp. During these brief (and sometimes not so brief) periods, all sorts of ‘essential’ information is exchanged, and if need be new decisions pertaining to the planned trip are made. The people in the car broadcast their intentions, the anticipated itinerary the trip will take, the intended composition of people going, ideas about the time of return and so on. From the people in the camp they receive similar information about other trips in preparation, as well as any other news and gossip the people in the camp have received from others passing by on their respective itineraries of cruising and ‘h&t’. Information about other hunting parties as well as other gossip is ‘exchanged’ and updated in turn at the next stop so that within the one hour or so of ‘h&t’ both the people in the car as well as most people in camps at Yuendumu will have been filled in on anything that there is to know. This is one reason why ‘h&t’ often includes quick stops at any of Yuendumu’s organisations and institutions, to quickly inform those who are at work of something just found out that may concern them.

To believe ‘hithering and thithering’ is caused by lack of organisation is to utterly fail to understand this practice, which fulfils a range of vital purposes. It is a central social practice shaping both social relations and the everyday. It underscores the fact that approval needs to be sought for most actions, however implicitly, e.g. in the case study approval needed to be sought for the purpose and destination from those people responsible for the country the trip was going to be made to. The ‘h&t’ in the first instance informs all people with a right to know of the intended trip and gauges its acceptability in terms of destination, itinerary and composition of people going. Highlighting the importance of this approval seeking is the fact that regularly after a bit of ‘h&t’ the planned destination and/or itinerary and/or the composition of people in the car change. It is not uncommon at all to start off with four people in a car planning to go hunting out east and end up with seven other people going west instead. ‘Hithering and thithering’ is about connecting people and places. The map in Figure 16 outlines the paths taken, and presents a visual image of the web thus spun during one particular episode of ‘h&t’. Realistically, what needs to also be taken into account is the fact that simultaneously to us driving around, other cars with other people in them were occupied in the same activity, as well as the numerous paths taken by people involved in cruising. If one were to draw a map of the entire extent of ‘h&t’ and cruising taking place at Yuendumu during one hour, the illustration would be black with lines, underscoring the intensity of lived sociality and the multitude of social interconnections interweaving with each other at Yuendumu during the day.

Ending the day: firewood

As the day comes to its close, the intensity of sociality lessens and subsides gradually. The focus shifts from settlement-wide interactions to spatially and socially more concentrated ones. I discuss this refocus to domesticity at the end of the day by examining issues surrounding the gathering of warlu (firewood).17 The example of firewood underscores this refocus as well as the previously made point about the often-occurring fractionisation of camp residents and reinforces issues about relatedness negotiated over commodities. Negotiations revolving around firewood are a central everyday occurrence at Yuendumu.

Only a small number of camps/houses, populated by people in their mid-twenties and younger, use firewood rarely, while almost all other camps use firewood regularly, and many of them depend exclusively on firewood for both cooking and warmth. Firewood is not available within walking distance of the settlement, and transport is necessary to acquire it — making it a valuable and often scarce commodity in high demand. The Council, CDEP, and the Old People’s Program all have commitments towards providing Yuendumu residents with firewood; however, this is a task often neglected. Camps whose residents are overwhelmingly old and/ or female, which are in the main also the camps most heavily dependent on firewood, have particular difficulties in obtaining amounts adequate to their needs, due to a lack of access to transport. Residents in these camps have to rely on being able to persuade relatives owning cars to help them, which may put strains on these relationships, especially in winter, when daily firewood trips become necessary to meet all the needs for warmth and cooking. The negotiations revolving around firewood throw light on sharing, asking, distribution, and conflict. Starting with the rare examples of two situations of an abundance of firewood and what happened, I work towards the more ‘normal’ scenario of firewood supply being scarce but present, concluding with examples of social tensions being expressed through negotiations about firewood ‘ownership’.

The social limitations on the capability to accumulate

While stopping in the jilimi, I was involved in daily trips for firewood, both for the jilimi and for a number of other camps in which resided people I was working with. In the winter of 1999, as it became colder and colder, requests for firewood trips increased to such an extent that they hindered me from doing other work. The jilimi residents, more aware of this than others, suggested I borrow a large trailer so that I could get a week’s supply for them which would help free me up to do other work. We went out three times with the trailer, piling it up high each time, resulting in an enormous amount of firewood in the jilimi. Very pleased with the thought of at least no more jilimi firewood trips for a while I was able to spend the day elsewhere in Yuendumu following up other issues. By the time I returned to the jilimi in the late afternoon all the firewood had disappeared. Getting such an enormous amount in fact meant that it lasted less time than a small pile normally did. This was because all the neighbours of the jilimi, like us dependent on firewood and undersupplied, saw the enormous pile and many came over to ask for ‘just a little’. The news that there was a huge pile of firewood in the jilimi spread like wildfire and people from a bit further away came too. Nobody could be refused any firewood, on two accounts. First, the jilimi had heaps, and therefore giving a little to others was the only decent thing to do. Second, since many others had received ‘their share’, nobody else who asked could be refused. By late afternoon we had nothing left ourselves, and I had to go out again to get some more.

It is simply not possible to store a large supply of something that is in demand by others for one’s own use. My frustration about firewood that day was paralleled earlier by Joy’s frustration about butter. She declared: ‘I will not buy butter again. I eat a little and then, put it in the fridge, somebody will eat it. Leave it outside the dogs will eat it or it will melt in the sun. Buying butter is a complete waste. Someone will take it anyway.’ The point in both cases is that if one has more than one needs for immediate use, others will use it. The traditionalist hunter-gatherer literature has for long argued whether one or the other of two preferred moralities underlie this phenomenon (see among many others Bird-David 1992; Hawkes 1993; Hiatt 1982; Ingold et al. 1988; Lee and DeVore 1968; Sahlins 1972; Testart 1987; Williams and Hunn 1981; Woodburn 1982). Is this simply a manifestation of an altruistic ethic of generosity or is it a more calculated sharing of things in abundance with a view to receiving returns later when in need? This argument was developed further by Peterson (1993; 1997) who argued for a reconsideration of the meaning of ‘generosity’ and postulated the practice of ‘demand sharing’ to be essential to any understanding of such activities.18 This often overlooked practice not only sheds light on vernacular ideas about generosity but is an intrinsic element of Aboriginal social life as interpersonal relations are structured around it. Peterson says:

Demand sharing is a complex behavior that is not predicated simply on need. Depending on the particular context, it may incorporate one, some or all of the following elements. It may in part be a testing behavior to establish the state of a relationship in social systems where relationships have to be constantly produced and maintained by social action and cannot be taken for granted. It may in part be assertive behavior, coercing a person into making a response. It may in part be a substantiating behavior to make people recognize the demander’s rights. And, paradoxically, a demand in the context of an egalitarian society can also be a gift: it freely creates a status asymmetry, albeit of varying duration and significance. (Peterson 1993: 870–1)

The case of what happened to the jilimi’s huge pile of firewood in the middle of winter when everybody around was complaining about their lack of firewood incorporates all the above-mentioned elements. The residents of the jilimi felt there was no option but to respond to all demands made on them for firewood until they were out of firewood themselves — in the light of the huge pile previously visible to all who came past, the only polite way to refuse further requests was to be able to say honestly that there was ‘nothing left’ and therefore nothing to give. This giving of firewood did indeed create asymmetry, and return demands by jilimi residents over the next weeks were generally answered (often not in kind, as there are many things to demand). It was a peculiar situation, however, since such a ‘flaunting’ of a scarce good is rather unusual, and stimulated increased requests from others for a share to such an extent that nothing was left for jilimi residents themselves. This example contrasts starkly with the following case.

A few weeks later that winter, CDEP organised some firewood runs, involving the labour of a number of men and a large CDEP truck. They dropped off truckloads of firewood at specific camps, chosen because of their residential composition, which put them in a higher ‘need’ category than other camps. Because of its large proportion of older women, our jilimi was one of the recipient camps, as was the jilimi right next door to it. This created a situation where two neighbouring camps in Inner West Camp each received a truckload of firewood while none of the surrounding camps received any (this situation was mirrored in other parts of Yuendumu). The CDEP objective was made public and everybody knew that this particular firewood was for ‘the old and needy’ only. Demand sharing happened to a much smaller degree and these truckloads of firewood lasted for a little over a week.

During this time Celia came from Willowra for one of her frequent stays in the jilimi. She had gathered some firewood on the way to Yuendumu and brought this with her. The day after her arrival she took me aside and asked whether we could go on a firewood trip. I replied that there was a large pile there and why did she not use some of that? ‘No,’ she answered, ‘that one CDEP warlu [firewood], it belongs to the jilimi, I can’t use him’. Celia and I went out to get her some firewood, which she kept in a small pile next to her yunta.

During this time Celia often used and sat around other residents’ breakfast and dinner fires (fuelled by CDEP firewood). However, she used her own wood for the warmth fire at night, thus making implicit statements both about different uses of different types of firewood and about her relationship to the jilimi and its other residents. Her refusal to use for her own purposes the firewood delivered by CDEP for the jilimi, of which she was a resident, makes an interesting contrast to the almost public demand sharing which consumed the above described pile of jilimi firewood within hours. Hers was a declaration both about her independence (not using the wood of ‘the old and needy’) as much as about her usual residential status. Being from Willowra meant that although she regularly stayed in Yuendumu, she did not use the wood provided for Yuendumu old people by Yuendumu CDEP, fully aware of the implications this would have had for her if fights had arisen. Further, this is a case of firewood being distinguished into different kinds, the CDEP pile being reserved for specific people and purposes, and her own one allowing her to use it as she pleased.

My firewood, your firewood, our firewood

Often, the jilimi had one pile of firewood only, which all residents used. As long as relations in the jilimi were amicable this worked well. However, when tensions arose this became ‘visible’ by people’s behaviour towards firewood before they were verbally aired. An increasing number of piles of firewood in the one camp indicates that things are running less smoothly than is ideal. I discuss three separate firewood trips to illustrate the relationship between firewood and sociality.

While Celia was still staying in the jilimi, I went on a firewood trip with her, Joy, and two other women from two camps in East Camp. We drove to an area north of Yuendumu through which a bushfire had recently gone (in the desert, firewood collection is easier after a bushfire, not only because the spinifex grass is burnt down but also because large and heavy trees, wood from which burns longer than the dry wood normally gathered, are more easily breakable). I parked the car and the four women and I went off in different directions in search of good firewood. About half an hour later, I loaded up my wood and then drove past their respective piles and we loaded them unto the back of the Toyota, all the while making sure that wood from different piles did not mix. I first dropped off the other two women and their piles at their respective camps, then we drove to Joy’s divorced husband’s camp where she dropped off half of her pile. As Joy moved between his camp and the jilimi (mostly sleeping in the latter and eating in the former), she was responsible for firewood in both. Then we drove to the jilimi and unloaded our piles in three separate locations: Celia’s next to her yunta along the eastern fence of the jilimi yard, Joy’s wood on the eastern side of the verandah, where her yunta was located at the time, and mine in front of the kitchen for the use of the remaining jilimi residents.

A second firewood trip later that week did not end quite so peacefully. This time, I dropped off Polly, Nora and Celia half way on the road to Mt Allan, where I was heading with Pearl to collect her pension cheque.19 On the way back we picked up the others and loaded the wood they had gathered onto the back of the Toyota. Nora had standard firewood only, while Polly had also gathered some wood for producing artefacts to sell on a planned trip to Melbourne, and both Polly and Celia had found some extra heavy long-burning firewood. While I was loading the wood onto the Toyota all three women gave minute instructions as to where to put it, which was basically that each woman’s logs were to be put as far away as possible from the others’. When we arrived in the jilimi, a fight broke out between Polly and Celia, with accusations flying about wood theft. While they were fighting, Nora proceeded to unload, and (accidentally?) took some of the coveted heavy wood, in turn drawing her into the argument as well. The yelling and screaming over that particular load of wood, containing lots of ‘this one’s my wood’, ‘that one’s your wood’, stands in stark contrast to the idea of demand sharing in connection to firewood described above. This particular case of fighting over firewood was fuelled by the emotions about a trip to Melbourne. Originally all three women were to go on the trip but earlier that morning the Kardiya woman who was organising the trip had told them that there was only enough money for Polly to travel. Celia’s and Nora’s anger, due to their disappointment about not being able to go, and some envy because Polly was, did not get played out verbally. Instead the emotions about it were transferred to the issue of ‘wood ownership’.

Lastly, as often as there were separate piles of firewood in the jilimi, we had only one communal pile. This happened when relations between residents were relaxed and amicable. On these days, people from different yunta came on the one firewood trip and the firewood was randomly piled onto the Toyota and then unloaded as one pile somewhere central in the jilimi — for everybody’s use. The use of and negotiations about firewood thus parallel other markers of the nature of social relations: ideally, firewood is shared by all within the jilimi. Just as often, though, rifts in social relations are expressed through the separation of firewood into different piles for the uses of different social fractions.

Night-time, daytime and webs of sociality

The state of restfulness of the night stands in stark contrast to the intensity of daytime social engagement. During the day, the boundary of the jilimi (and for that matter, that of any other camp) is highly permeable, accommodating flows of visitors in and out of the jilimi as well as residents’ own movements. Daytime social practice, rather than being camp-focussed, is about social engagement settlement-wide. This engagement takes an elliptical course, beginning slowly in the morning with a camp internal reordering for breakfast and first inter-camp visitation, then increases steadily to heightened hive-like activity with which the settlement ‘hums’ during the day, to the diminishing volume of interactions toward the evening with a refocus on domestic matters. Individual camps and the settlement space complement each other in terms of being locales of social interaction. During the day and throughout the settlement, webs of sociality are created, lived, and reinvented, which are at night ‘recorded’ in the sleeping arrangements in individual yunta in the camps. The settlement thus needs to be factored into any discussion of ‘domestic space’ as it operates as a daytime extension of Yuendumu’s camps.

During the day and across the settlement, webs of sociality are created through social practices that are part of the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking. These webs of sociality are incessantly spun, maintained, broken, repaired, expanded, and renewed through the crisscrossing paths of mobility. People are constantly on the move, cruising and ‘hithering and thithering’, interconnecting with others, exchanging, discussing, finding out, thus creating the ‘feel’ of immediacy. Intimacy is drawn upon and generated by connecting people along the lines of damper distribution, visiting, through exchanges of gossip and news, co-cruising, and being in the same places. Lived out together in daily interaction and social practice, the values of mobility, immediacy and intimacy engender the very stuff that makes the Yuendumu everyday so distinct. As a result, Yuendumu as the physical manifestation of a remote settlement is a space which is neither fully part of the Western series of building–dwelling–thinking nor fully part of the Warlpiri series of building–dwelling–thinking, but one that encapsulates the intersection of both.