Smoke is the spice that is not on your spice rack. There are three sources of smoke in outdoor cooking: drippings, fuel, and wood.

Drippings of juices and fats, often laden with spices, vaporize when they hit hot surfaces, fly up, and land on the food, imparting aroma and flavor.

Fuel is the material that combusts to produce the heat. An electric grill produces no smoke or gases. A gas grill, when properly adjusted, produces water and carbon dioxide but no smoke. Charcoal is wood that has been preburned and converted to carbon. When it is just firing up it can produce a lot of billowing smoke, but when it is fully engaged and burning hot there is only a little smoke, unless the wood was not fully carbonized in the production process. Wood pellet cookers burn pure wood sawdust compressed into pellets and they produce wood smoke, more at lower combustion temperatures. Finally, there are logs, which produce the most complex and interesting aromas and flavors.

Wood smoke is the essence of barbecue. When we aren’t burning logs as fuel, we can get wood smoke by throwing wood onto our grills and smokers, even if they use electricity or gas.

How Smoke Flavors Meat

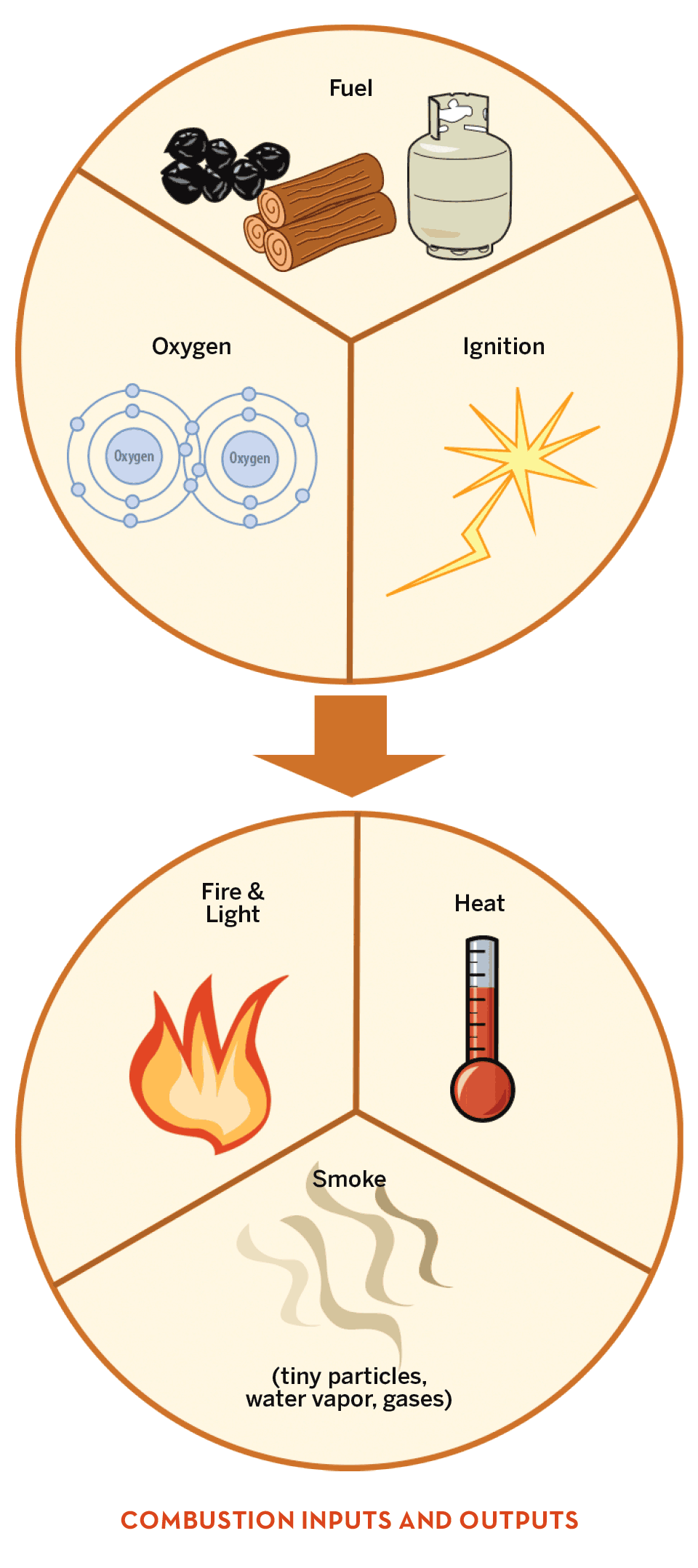

Wood combustion starts to take place in the 500 to 600°F range and requires significant amounts of oxygen. The actual temperature depends on the type of wood, how dry it is, and other variables. Let’s call the average combustion point 575°F for the sake of discussion. The heat of ignition drives water and flammable gases out of the wood, and many of them burn if there is enough oxygen. The combustion of these gases is what produces flame. If all the gases combine with the oxygen, the flame appears blue, as in a well-tuned gas grill, and there is no smoke. If the gases don’t burn completely, the flame glows yellow or orange. If unburned gases escape, they cool and turn into part of the smoke.

Smoke is complicated stuff, and there are different types. Smoke from burning wood contains as many as one hundred compounds in the form of microscopic solids, including char, creosote, ash, polymers, water vapor, and phenols, as well as invisible combustion gases such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen oxides. When these compounds come into contact with food, they can stick to the surface and flavor it. Most of the flavor comes from the combustion gases, not the particles, and the composition of the gases depends on the composition of the wood, the temperature of combustion, and the amount of available oxygen.

As smoke particles and combustion gases touch the surface of wet foods like meats, they dissolve, and some are moved just below the surface by diffusion and absorption.

Building up smoke flavor on the surface of food takes time. A thin skirt steak cooks in minutes, so it will take on less smoky flavor than a 2-inch-thick ribeye steak will. A ribeye will have a less smoky flavor than a 3-inch thick turkey breast, and a 4-inch thick beef brisket cooked low and slow for 12 hours will pick up a ton of smoke.

Myth Creosote in smoke must be avoided at all costs.

Busted! Pitmasters think creosote is the boogeyman because they’re confusing it with creosote from coal tar: the black stuff used to preserve telephone poles and railroad ties. Despite the similar name, coal-tar creosote is chemically distinct from wood-tar creosote.

Wood-tar creosote is always present in charcoal or wood smoke, and a few of its components—specifically guaiacol, syringol, and some phenols—are crucial contributors to smoke aroma, flavor, and color in foods. Without creosote, the meat might as well have been boiled.

Creosote is the Jekyll and Hyde of smoke cooking. On the Dr. Jekyll side, it contributes positively to the flavor and color of smoked foods and acts as a preservative (smoking meat was used for preservation before refrigeration). On the Mr. Hyde side, if the balance of chemicals in creosote shifts, it can taste bitter rather than smoky. The trick is getting the balance right.

When you smoke low and slow at temperatures like 225°F, many smokers require you to control the fire by damping the oxygen supply. This moves the fire below the ideal combustion zone, creating black smoke, soot, and bitter creosote. The best smokers combust at a high temperature to create the ideal flavor profile.

Smoke and Food

Think of smoke as a seasoning, like salt. Use too much, and you can ruin the meal.

In a smoker or grill, after combustion, the smoke rises and flows from the burn area into the cooking area. Some of it comes into contact with the food, but most goes right up the chimney and very little deposits on the food.

Around every object is a stagnant halo of air called the boundary layer. Depending on airflow and surface roughness, the boundary layer around a piece of meat might be a millimeter or two in thickness. When smoke particles approach the meat’s surface, small ones follow the boundary layer. Only a few of the larger ones touch down. We’ve all encountered a similar phenomenon while driving: Gnats follow the airstream over the windshield, while larger insects leave sticky green splats at the point of impact.

To demonstrate the way smoke sticks to food, we did some experiments. We painted three empty beer cans white. We filled one can with ice water and left another empty, and both went into the smoker. The control sat on my desk. After 30 minutes, both cans in the cooker had smoke on the surface, but the colder can had a lot more. That’s because cool surfaces attract smoke, a phenomenon called thermophoresis. Another factor was at play. The cold can also attracted water in the atmosphere and in the combustion gases, which condensed and ran down the can. Smoke particles stick better to wet surfaces.

Similarly, if meat is cold and wet, it will hold more smoke. As the meat warms and dries out, smoke bounces off. It’s the same reason a cold mirror holds on to steam from a hot shower.

Smoke Flavor Is Almost All on the Surface

Smoke particles glom on to the surface of foods. They may dissolve and penetrate a bit below the surface but rarely more than ⅛ inch into the microscopic fissures and valleys of the meat, because their molecules are too large. Meats are especially hard to penetrate.

Myth The more smoke you see, the better.

Busted! Actually, the opposite is true. Billowing white smoke may mean there’s a new pope, but the barely visible wisp of blue smoke is the holy grail to low-and-slow pitmasters.

If gas or charcoal is your fuel, start with less wood than you think is needed as you are learning your cooker. Very tight, efficient smokers like kamados will need much less wood than a gas grill that is heavily ventilated.

The Smoke Ring

Smoked meats, like the brisket shown on page 17, often have a pink layer directly below the surface, nestled neatly under the crust. This is called the smoke ring. Alas, every year thousands of restaurant customers send back meat, especially chicken and turkey, claiming it is undercooked because it is pink. It is not underdone. Smoke rings have long been emblems of authentic wood-smoked barbecue. Backyarders know they have arrived when they make their first smoke ring. Barbecue aficionados look for smoke rings to prove the meat was wood smoked.

4 Secrets to a Smoke Ring

No matter what cooker you use, the secrets to a great smoke ring are all related to moisture:

1. Maintain high humidity in the cooker to keep a moist surface on the meat that will attract smoke. A water pan helps.

2. Maintain a steady, low temperature of about 225°F to minimize drying on the surface of the meat.

3. Add water manually by basting or spritzing the meat. Spritzing with apple juice or vinegar is a popular method.

4. Start with cold meat. Water vapor will condense on the cold surface like it does on a beer can on a sultry July day.

Myth A smoke ring is caused by billowing smoke.

Busted! You can actually make a smoke ring without smoke! Myoglobin, which is naturally reddish pink, often turns gray when heated. But some compounds can prevent myoglobin from changing color. Curing salts, which have nitrites and nitrates, make corned beef and hams permanently pink. In competitions, unscrupulous cooks have been known to sprinkle curing salts on meat to fake a smoke ring.

When smoking meats, invisible gases nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) mix with wet meat juices and basting liquids and lock in the color of myoglobin. However, the dissolved gases cannot diffuse very far beyond the surface of the meat before the interior heats up. This dooms the myoglobin in the interior to its usual gray fate. As a result, pink smoke rings usually go only about ⅛ to ¼ inch deep.

As the meat cooks, the surface of the meat begins to dry and less smoke sticks to the surface. That’s why putting a pan of water in a smoker helps create a smoke ring by giving the gases more moisture to stick to. In fact, some smokers, called water smokers, have built-in water pans.

Myth After an hour or two, meats stop taking on smoke.

Busted! Meat does not have windows that shut as it cooks. If the surface of the meat is cold or wet, more of the smoke sticks. Usually, late in the cooking, the surface gets pretty dry, and when the coals are not producing a lot of smoke, we are fooled into thinking the meat is somehow saturated with smoke. Throw on a log for smoke and baste or spritz the meat, and the meat will start taking on smoke again. Just don’t overbaste or aggressively spray, because in seconds you can wash off the smoke that took hours to build up.

Buying Wood

The key to producing great-tasting smoke? Great wood. Hardwoods, fruitwoods, and nutwoods are the best woods for most types of cooking because they have compact cell structures and burn slowly and evenly. Steer clear of softwoods such as cypress, fir, hemlock, pine, redwood, spruce, and cedar. The wood from coniferous trees contains a lot of air and sap, which makes it burn fast, produce unpleasant flavors, and pop, crackle, and spark. Food cooked over some of these woods has been known to make people sick.

You want wood that’s been properly dried. Fresh-cut wood has a lot of water in it—up to 50 percent by weight—so it produces a lot of steam as well as funky flavors and aromas during combustion. Even dried wood is rarely totally dry, with perhaps 5 to 20 percent water left, but some water is OK. Of the remaining mass, about 38 percent is cellulose (a type of carbohydrate), 38 percent is hemicelluloses (carbohydrates and sugars), 18 percent is lignin (a polymer that strengthens the wood and is responsible for most of the wood flavor and aroma), and 1 percent is minerals. The actual percentages will vary depending on how the wood was dried, the species and subspecies of the tree, its age, and the soil and climate in which it was grown. The minerals are especially important because they affect the smell and taste of the smoke.

Hardwoods, fruitwoods, and nutwoods are the best woods.

You may be able to scrounge decent wood from forests or orchards whose owners will let you gather dead trees, branches, and prunings. Just make sure you get clean wood, free of pesticides, mold, mildew, and rot, all of which could be toxic or impart off flavors to your food.

A local cabinetmaker or flooring installer will often have a wide range of scraps of kiln-dried, tight-grained chunks, chips, and sawdust. Choose hardwoods like oak, cherry, and maple. Make sure the wood is pure hardwood, untreated and unstained. If you thank your supplier with a slab of ribs now and then, you might get a lifetime supply of free wood.

The best method is to buy wood specifically intended for smoking. It is available in many forms: logs, chunks, chips, pellets, bricks, bisquettes, and sawdust.

Logs. Many small companies sell logs for fireplaces, usually by the cord or face cord. A cord is 128 cubic feet, or a neatly stacked pile about 4 feet high, 8 feet long, and 4 feet deep (usually cut into 2-foot lengths). A face cord is one third of a cord. You want a reputable dealer who can be trusted when he says the wood is apple, cherry, or whatever. You can buy smaller bundles in hardware stores, at campgrounds, and even in convenience stores, but you really can’t be sure what is in the bundle, no matter what is on the label.

The quality of the meat, the spice rub, the sauce, and the temperature affect the final taste profile far more than the name on a bag of wood.

The wood should be dry, with a low percentage of bark. Wood is dried two ways: drying naturally outdoors for at least a year, or drying in an oven called a kiln. Kiln-dried wood is much more expensive. If you’re buying freshly cut wood, you can dry it yourself. Try to store it off the ground (stacking it on old shipping pallets works well) and keep it under a cover that will protect it from rain and snow. The shorter the length of wood, the faster it dries. Properly stored, firewood can be kept for years.

-

Chunks. Wood chunks from golf ball to fist size are fairly easy to find in hardware stores. They burn slowly and steadily, and often a chunk or two is all that is necessary.

Chips. About the size of coins, chips are also common and easy to find in hardware stores. They burn quickly, and you may find that you need to add them frequently during the cooking cycle. They burn hot and fast, creating blue smoke (see below).

Pellets. Food-grade pellets are compressed sawdust extruded into long, pencil-thin rods that are broken into bits about ½-inch-long. They contain no binders, glue, or adhesives. When wet, they revert to sawdust immediately. Pellets can be a good concentrated source of smoke flavor on charcoal or gas grills and smokers.

Pellets for household heating should not be used for cooking because they may include pine or binders, and because the machines used to make them are lubricated with petroleum. Food-grade pellets, on the other hand, include only hardwoods, and the manufacturing equipment is lubricated with food-grade oil. They usually come in 10- to 40-pound bags.

Most pellets are made from oak, a stable-burning wood. If the label says hickory, the pellets are usually less than half hickory and the rest is oak, a fact that does not always appear on the label. These products are easy to measure and control. They burn for only about 20 minutes at 225°F, so get your meat on the cooker before adding the pellets.

Blocks. Similar to the pellet is the block. Wood chips and sawdust from lumber mills are compressed into blocks about 3 to 4 inches on each side. They come in a variety of flavors. I have had very good luck with them on a number of smokers.

Bisquettes. A variation on compressed sawdust, bisquettes are designed for the Bradley Smoker. They look like small brown hockey pucks and are stacked and gravity-fed into the smoker.

Sawdust. Sawdust burns so quickly that it’s rarely used for barbecue. A few small stove-top smokers use smoldering sawdust for a light smoke flavor. You can often get sawdust from cabinetmakers.

Specialty wood. Some manufacturers like Weber and Char-Broil sell perforated aluminum pans containing the wood flavor of your choice. Kingsford also makes a “briquet” that is not charcoal but pure wood.

Which Wood?

When you are using wood as your primary fuel, which wood you choose is crucial for both heat and flavor. It’s much less important when you are throwing a few chips or chunks into a pile of charcoal or onto a gas grill or pellet smoker.

For me, wood flavor can be broken down into two simple categories:

Mild. Alder, cherry, grape, maple, mulberry, oak, orange, pecan, and peach. Best for foods that are not heavily seasoned or sauced.

Strong. Apple, walnut, hickory, mesquite, and whiskey barrel. Best for strong-flavored foods with lots of spice or sauce or for food that cooks quickly, like fish or thin cuts of meat.

If I were forced onto a desert island, I’d want three types of wood: apple chunks for steady smoke flavor, cherry chunks for a pretty reddish color on the bark of the meat, and apple chips or pellets for quick smoke during short cooks.

I cannot state this more emphatically: The quality of the meat, the spice rub, the sauce, the cooking temperature, and the meat temperature affect the final taste profile far more than the name on a bag of wood.

Myth It’s important to match the wood to the meat.

Busted! Books and websites love to publish tables proclaiming, “Applewood goes with pork, maple with chicken, hickory with beef.”

Humbug. I laugh at all the guides that attempt to describe different wood flavors. They remind me of the florid descriptions that wine critics use. Think about it. Apple might taste one way on pork but it will taste entirely different on beef or turkey.

What kind of hickory? Shagbark hickory or pignut hickory? Bark or no bark? Logs? Wood chunks? Wood cured for three years or less than a year? How much wood did you add? How hot was your fire?

Shagbark hickory logs from the Finger Lakes will taste different than barkless pignut hickory chunks from the Napa Valley.

I’ll admit that mesquite is so strong it is pretty easy to taste. And on some foods, like delicate fish, wood differences are more obvious. But most of the time, the smoke flavor is lost under the flavor of the meat, rub, and sauce. And frankly, that’s OK with me. Smoke should just be another instrument in the orchestra, not the soloist. Bottom line? Stop obsessing over which wood to use. Just pick one and stay with it for a while. Keep the variables to a minimum. Once you have everything else under control you can try experimenting with different woods.

The Quest for Blue Smoke

Not all smoke is created equal. When it comes to cooking, we want thin, pale-blue smoke if possible. The smoke color depends on the particle size and how it scatters and reflects light to our eyes. Pale-blue smoke particles are the smallest. Pure white smoke consists of larger particles. Gray smoke and black smoke are produced when the fire is starving for oxygen and the smoke particles become large. Dark smoke can result in bitter, sooty food that tastes like an ashtray.

Billowing white smoke is common when you just start the fire, and when the fuel needs lots of oxygen. It does not taste bad, but it is not as good as blue smoke. If you are cooking something hot and fast, like a steak, white smoke is a great way to get some smoke flavor on the food in a hurry. Otherwise, go for blue.

Sterling Ball, a champion pitmaster who owns the famous Ernie Ball guitar string company, describes the art of making blue smoke as similar to tuning a guitar: “You need control of your tools, the pit, fuel, oxygen, fire, heat, and practice.” Here are some tips on how to get blue smoke.

Keep your cooker clean. Carbon buildup, soot, creosote, and sticky grease on the inside of your cooker can create greasy smoke. Often that grease is loaded with the bad kind of creosote.

Use aged wood. If wood is your heat source, use aged and dried wood. Green woods have more sap, burn irregularly, and impart different flavors than aged woods.

Avoid wet wood. Keep the wood out of the rain. Some pitmasters will put logs on top of their smoker to evaporate excess water before adding them to the fire.

Build a small, hot fire. Low-smoldering wood creates dirty smoke, while hot fires burn off any impurities. You want to see flame coming from the wood. That means that you need a lot of oxygen. Open your exhaust vent so the hot air rising through the chimney draws in air through the intake vent. Open the chimney wide or close to it. Don’t let your embers sit in ash; keep them on a grate above the bottom of the firebox. Knock ash off occasionally and, if necessary, remove the excess. If coals are choking for lack of oxygen, they will burn incompletely and can coat your food with gray soot. If that happens, get the meat out, rinse it, adjust the fire, and put the meat back on.

Allow the pit to warm up. Start the fire at least an hour before the food goes on. Adjust your airflow and get the temperature, fire, and smoke stabilized. Warm the walls of the cooker. It is harder to get blue smoke in a cold environment. Warm walls will also prevent greasy buildup.

Start the fuel on the side. Add mostly hot coals. If you are cooking with wood, start burning it on the side and add only glowing embers. If you are using charcoal, use briquets. Lump charcoal is often not completely carbonized and can create more smoke than briquets. Remember, properly burning charcoal doesn’t produce much smoke, but when you first light charcoal it produces lots of smoke. I use a chimney starter to start briquets.

Use good thermometers. As with everything in barbecue, getting blue smoke is all about temperature control. Cooks who say they don’t need thermometers are either seasoned old-timers who learned at the foot of a master and have been doing it for years, or they’re macho knuckle draggers.

Cook on indirect heat. If the meat drips on the fire, water and fat will burn and make greasy, pungent smoke. These drippings can create flavor, especially for short, fast cooking, but for long, low cooking, they can create dark smoke. Keeping the meat in indirect heat means fewer flare-ups.

try small chips or pellets. On some cookers chips and pellets combust and disappear quickly, but they burn hot and fast and make better-quality smoke. Chunks smolder and produce dirtier smoke.

Use your senses. It’s hard to see the color of the smoke at night, but the smell should be sweet, with meat and spice fragrances dominating. The smoke aromas should be faint and seductive.

Use the right amount of wood. The amount you need may vary according to your preferences, how tight your cooker is, the type of fuel, the thickness of the meat, and if you use chunks, chips, or pellets. Pellets are especially good for measured amounts. On a charcoal grill, start with 4 to 6 ounces of wood by weight for turkey and chicken. Use 8 ounces of wood for ribs, and no more than 16 ounces for pulled pork and brisket. Start with 2 to 4 ounces when you put on the meat and add another 2 ounces when you can no longer see smoke. On gas grills, double the amount. The proper amount depends on your cooker.

Practice. Do dry runs without food in your smoker until you can anticipate when more fuel is needed. Know how to adjust the airflow, and know how to react when the smoke starts going bad.

Take notes. Weigh the wood before you add it and write down amounts and times so you can adjust it the next time you cook.

Myth Soak wood chips and chunks for the most smoke.

Busted! To test whether soaking wood is effective, we weighed some wood chips and chunks on a digital scale. Then we soaked them in room-temperature water for 12 hours. Then we removed them, shook off the surface water, patted the exterior lightly with paper towels, and weighed them again to see how much water had been absorbed. Large chunks gained about 3 percent by weight and small chips about 6 percent. That’s not much. Chips absorbed more because they have much more surface area than chunks.

To see just how far water penetrates into wood, we soaked three pieces of wood (a solid block of oak, a chunk of cherry, and a chip of cherry) for 24 hours in water mixed with blue food coloring. We then rinsed the surfaces, patted them dry, and photographed the exteriors. Then we cut the wood in half. As you can see in the photos below, the dye discolored the surface only a little and entered the interiors only where there were cracks and fissures. The rest of the wood was bone-dry.

There’s another good reason not to soak your wood: If you toss dripping-wet wood onto hot coals, the water on the surface of the wood cools off the coals. The key to good outdoor cooking is to hit a target temperature and hold it there.

Wet wood will not rise much above 212°F until the water steams off. Only after the water evaporates and the wood warms to the combustion point at about 575°F does it produce smoke. Most of that white stuff you see when you throw wet wood on the fire is steam.

Finally, I emailed fifteen top competition teams. Not one of them soaks their wood.

Smoke Bombs

This method is ideal for when you are cooking for a long time and getting under the grate will be tricky. This is one case when I advocate for wet wood.

Get two disposable aluminum pans. Add dry wood to both. Pour enough water in one to cover the wood and put both pans in the cooker. The dry pan will start to smoke quickly. About 15 minutes after it is all consumed, the other pan will have dried out and begun smoking.

Troubleshooting Chips and Chunks

Sometimes wood chips burst into flames. This can actually be good. With flames, you get clean combustion and blue smoke. You go through a bit more wood than when it smolders, but you get better flavor. However, the heat of the burning wood can drive your temperature too high. To prevent this, make a smoke packet by wrapping the wood in aluminum foil. Use heavy-duty foil or two or three layers of regular foil and poke holes in it. Then put the pouch on the grill as close to the heat as possible. Make several pouches in advance. When one has burned up, throw another one on. Another option is to use a small aluminum pan with holes poked in the bottom. You can even put the wood in a small cast-iron frying pan.

Smoking with Herbs

I have a small herb garden, and at the end of the season, I always have a few unpicked oregano and basil bushes. I cut them above the roots and stick them in paper bags to dry. Then I crumble them and throw them on the grill after the food is on. They burn fast and add exotic aromas. I use them mostly when cooking fish and shellfish on my gas grill, since they cook quickly and don’t have time to absorb slow-smoldering hardwood smoke. You can also smoke with tea leaves and spices, as is popular in China.