Sometimes a Samoan looking at the representation of his culture’s past in works of history - no less than in the present representation by anthropologists - may wonder whether the cultural roles of such Samoan devices as the riddle, camouflage, and even propaganda and the nature of genealogy have been quite understood.

The riddle is premised on Samoan theology. God pronounced in oracular fashion and the chiefs as descendants and heirs follow suit. When a chief lusts in the confessed fashion of former United States President Jimmy Carter for your daughter he says in oracular fashion ‘I need a perch for my pigeon’; in fact, he is saying in a riddle, ‘I want your daughter to be my wife’.

Mannered language is allusive, so when I have had a gutsful of fighting and want to pick up my marbles and go home, I say allusively, ‘My blood lies in the thick bush and my body is hissed like the owl by the birds in the forest.’ Instead of responding: ‘Oh! don’t be a ninny,’ the other party parries elegantly: ‘Ah! Patience, let us cast our net once again for we may catch a sacred fish [turtle] that you can take home as a suitable trophy!’

And while waxing poetic when grateful, one might venture: ‘I cannot possibly return your hospitality, but this I will say to you: my love for you I shall not expose to the air lest it turn mouldy nor shall I put it to the ground lest the maggots get to it, my love for you I will place between my heart and my lung so that as long as I have breath it too will have life.’

Samoans, on the other hand, can be perverse in the way they name people, like Safeofafine, meaning the sanitary pad of a menstruating woman, which is a jest about a man’s origin, conceived when his mother is in period. I am told by medical friends that it is possible - but the jest was made when it was common belief that it was not.

With regard to deliberate ambiguity or doublespeak intended as camouflage, fudging, hedging bets, or protecting exclusive language and knowledge of a cabal, Samoan practitioners are as adept as any academic, lawyer or politician. Wading through oracular pronouncements, allusions, poetry, perverse nomenclature, deliberate ambiguity and doublespeak in order to identify issues, define initiative and reaction and their interplay, and motive and objective is no simple chore. It requires a good command of the language, an understanding and a ‘feel’ for the culture.

Most of the historical commentators on Samoa, for example, Otto Stuebel, George Pratt, Augustin Krämer, mention the celebrated struggle between Tui Atua Fogaolo’ula and Tui Atua Foganiutea in the fifteenth century. The aftermath of their quarrel provides a crucial link between the lady Salamasina and the district of Atua.

But the identity of the two Tui Atua is a mystery. They do not appear in the listed genealogies nor is there an explanation of who they were in the written histories. How do we begin to look for clues in the puzzle? First, we search for a link.

Fogaolo’ula and Foganiutea we find are the names of residence sites not far apart in Saletele compound; Saletele was originally part of Fagaloa, now a subvillage of Falefa. The honorifics of Saletele provide another clue: recognition of Sefaatauemana as the taupou (belle) name for all the chiefs, which is a high honour. Sefaatauemana was the name of Mata’utia Faatulou’s mother. Mata’utia Faatulou’s father Lalovimamā was the brother of Atogaugaletuitoga, mother of Tupa’i and Tauiliili. Mata’utia Faatulou was the husband of Levalasi, the lady principally responsible for Salamasina’s acquisition of the four pāpā, the royal titles of Samoa.

From this point on we have to speculate unless tapu knowledge is accessible. I am going to break tapu for reasons I shall elaborate later. Tui Atua Sefaatauemana quarrelled with Lufilufi, left Lufilufi in a huff and established her household in Fogaolo’ula. Her daughter, also named Sefaatauemana, the Tui Atua’s taupou, followed her mother and set up her household in Foganiutea. Amituana’i, a chief of Aleipata, paid court to the mother and was accepted, and after the customary formalities they became husband and wife. Shortly after, the husband, in a manner of speaking, took up with the daughter, creating friction between mother and daughter on the issue of faamoetane - taking somebody else’s husband to bed - or mulilua - two muli - rear-ends, meaning an adulterous husband. Roughly translated: who seduced whom? The nub of the issue of course was a woman (and a mother at that) scorned. The quarrel became bitter and spilled over to titles. The daughter claimed the Tui Atua title. Atua was divided and the issue became the pretext for war. The mother called on her nephews by an earlier marriage, Tupa’i and Tauiliili. The nephews responded in the name of the war goddess Nafanua. Once victory was achieved Tupa’i and Tauiliili took away the pāpā Tui Atua and gave it into Nafanua’s keeping; and, to underline dominion, the title Tupa’i was imposed on Lufilufi, who had espoused the daughter’s cause.

The pretext was somewhat bizarre and the custodians of knowledge decided to camouflage it by referring to the protagonists by the names of their residences -thus Tui Atua Fogaolo’ula and Tui Atua Foganiutea. The work of historians becomes difficult when the custodians of knowledge decide to withhold information or specifically to camouflage embarrassing allegations.

Aside from language, a thorough grasp of genealogy, honorifics and names of, for example, people, house sites, land, villages and districts, is essential. Without this, even professional historians stumble and lose themselves in the welter of claim and counter-claim and propaganda.

R P Gilson, for example, writes: ‘The Samoans had no sanctions or rules restricting title succession to a specific heir - to the eldest son for example.’2 This is a serious error. There is a principle known as alii o aiga that recognises privilege or precedence accorded to the eldest male of the first official usuga (formal marriage alliance). There is a second principle known as suli sosoo, meaning precedence accorded to the immediate heirs, which one of the ranking Tupua titleholders, Galumalemana, attempted to perpetuate by creating a collective status for his immediate descendants known as aloalii, which Gilson translates as ‘princes of the royal blood’.3 Galumalemana was attempting to defeat cultural convention according to which his suli sosoo or immediate heirs’ rights were superseded by rights of the immediate heirs of his successor. To the extent that aloalii became a powerful pressure group in the politics of war and succession, Galumalemana’s objective was fulfilled. Gilson would have been spared error by the most elementary knowledge of genealogy. A cursory examination of Samoan genealogy shows that usually the alii o aiga principle is observed, i.e., the eldest male of the first formal usuga succeeds, or alternatively but less frequently, the suli sosoo, i.e., immediate heirs. The exception is where the successor is neither alii o aiga nor suli sosoo. In this case convention is subverted by mavaega (last testament), family or village preference, or by war.

Conventionally the alii o aiga is the manaia, which reinforces the former’s claim to succession. The manaia is the official head of the ‘aumaga (the formal name of the association of untitled men). The ‘aumaga is a formally recognised component of the village body politic. Manaia has the equivalent of matai status. As manaia the alii o aiga serves an apprenticeship by leading the ‘aumaga and striking bargains with other components of the body politic, for example alii and tulafale (formal grouping of chiefs), faletua and tausi (formal grouping of chiefs’ wives). Organising marriages of the manaia, like those of the principal chiefs, is a function of the village executive.

Foreign sponsors, such as merchants, land speculators, plantation owners and consuls pursuing conflicting agendas, ensured a long-lasting political hiatus. The new political equation spawned parameters which set aside centuries’ old convention. Claimants of pāpā or tafa’ifa did not found their claims on alii o aiga or suli sosoo and their advocates understandably denied the existence of sanctions or rules restricting succession. Opposing parties canvassed candidates for succession to titles as a way of winning allegiance of villages and districts. When it suited political convenience, parties promoted candidates outside the category of alii or aiga or suli sosoo. In these circumstances the parties had a stake in denying that succession was governed by rules. Today, because of the increase in members of the family, reluctance to create titles in recognition of prowess, and parameters imposed by the money economy, the principle of alii o aiga and suli sosoo is recognised by the Land and Titles Court as one criterion, but not necessarily the determining criterion. Gilson may have been influenced by propaganda or by the rationale of the Land and Titles Court.

Gilson equates the Tooā of Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi and the Tooa of Mataafa Iosefo and cites Krämer as his authority. This is again a serious mistake, that Gilson compounds by saying that Tooa is a title in Manono.4 There is no such title in Manono.

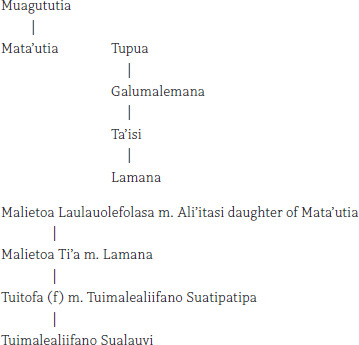

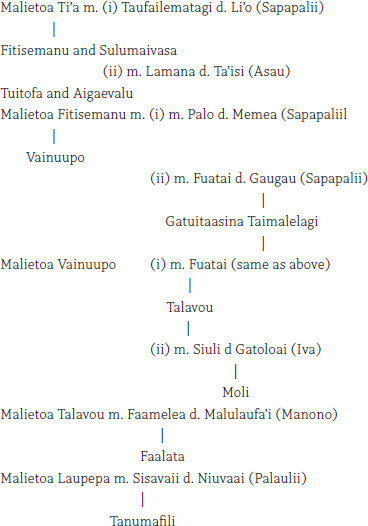

In Manono, Tooā is the taupou name of Leiataua Lesa. As to Tuimalealiifano’s Tooā, Malietoa Laulauolefolasa married Aliitasi (daughter of Mata’utia, descendant of King Muagututi’a) and sired Malietoa Ti’a, who married Lamana (daughter of Ta’isi, grandson of Tupua) and sired Tuitofa (f), who married Tuimalealiifano Suatipatipa and sired Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi. By Samoan standards the union between Tuitofa and Suatipatipa is the equivalent of a marriage made in heaven. The fact that Tuitofa, aside from being the daughter of Malietoa, was also granddaughter of Ta’isi and a direct descendant of Muagututi’a gives her (and through her, her son Sualauvi) the highest status in the Malietoa hierarchy. Her status is reinforced by the fact that the mother of her brother, Malietoa Fitisemanu, was a daughter of Li’o of Sapapalii, and the mother of Fitisemanu’s son, Malietoa Vainuupo, was a daughter of Memea, again of Sapapalii. Sapapalii is one of the two villages in which the Malietoa titleholder officially resides.

Sualauvi was accorded Tama Sa status, the highest honour that can be given to the female line, and named Tooā, which gave him precedence over any other link and parity with the Malietoa titleholder. The allied Aana and Atua districts, exhausted by the long-drawn-out war of the 1850s and wary about the uneasy peace that followed, invited Sualauvi to be their champion. Sualauvi became in turn the Tui Aana, Vaetamasoalii Gatoaitele, and was poised to acquire the Tui Atua title when he fell ill and died. Because of his status the Malietoas did not oppose his acquisition of the Tuamasaga pāpā (Gatoaitele and Vaetamasoalii). Revealingly, missionary and consular commentators were indifferent to Sualauvi, preferring to focus on Malietoa Talavou, Malietoa Moli or Laupepa.

To the foreign commentators the principal determinant was commerce. Commerce was equated with Apia and control of the municipality. The main qualification for kingship was the wherewithal to acquire and retain control of Apia. Pāpā and the politics associated with pāpā were irrelevant so long as they did not impinge on the commercial imperative. Apia, situated in the middle of Malietoa territory, gave the Malietoa cause an advantage. George Turner, the missionary and author, premised his political involvement on this advantage.

Names and genealogy matter again in the case of Mataafa Iosefo’s Tooā. The mother of Mataafa Iosefo was the daughter of Futi, the foremost orator in Manono. Leiataua, principal chief of Manono through marital ties with the Malietoas, acquired the name Tooā for his taupou. As we have seen, both Malietoa and Leiataua’s taupou name is Tooā. Futi Mataafa’s grandfather was a descendant of Leiataua Lesa. Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi’s Tooā refers to Malietoa’s Tooā; Mataafa’s Tooā refers to Leiataua’s Tooā. Mataafa’s Tooā is no less distinguished in history and politics, given the role of Manono in the Samoan polity.

Manono ascendancy was at its peak by the time of Tamafaigā’s death in about 1828. Tamafaiga and his allies had defeated the Malietoas and subdued Atua/Aana. It is therefore unlikely that Aana, which had held the malo jointly with Atua for centuries, would be Tamafaigā’s ally as suggested by Gilson at the time of the former’s assassination.5

Taking pāpā away from Lufilufi and Leulumoega was not unprecedented. That part of Savaii represented by Tonumaipe’a title holders achieved as much just before the Salamasina era. Consistent with the Tonumaipe’a tradition, Tamafaigā did not assume the Tafa’ifa title. Tafa’ifa was irrelevant to the substance of power.

Now the manner of Tamafaigā’s death roused his adherents to a frenzy. Tamafaigā’s last moments were described by John Williams:

Immediately the beads were from his neck they struck him a blow with a sharp axe which severed it from his body; after which they carried him into the house, cut off his legs and his arms and parts of his generation. They then cut off his tongue, assigning their reasons as follows: they cut off his legs for gadding about to other peoples’ settlements, they cut off his hands for seizing other peoples’ property and dragging off their wives, they cut off his parts for having connexion with other men’s wives and they cut out his tongue for his intolerable insolence.6

There was proud Aana, defiant and alone. For centuries she had wielded power as the malo and yet in recent times had alienated her traditional allies in Atua and Savaii. Malietoa and his party saw the Tonumaipe’a bandwagon developing and decided to throw in their lot with the predictable winners. It was not, as some say, a war of succession but a war of revenge and reprisal. The atrocities perpetrated by the victors are evidence in support. To the extent that it was a war of revenge it was therefore more the Manono regime’s war than, as commonly believed, Malietoa’s. Malietoa was the defeated opponent who joined the malo party of Manono and Sa Tonumaipe’a to redeem the honour of the mutilated Tamafaigā and simultaneously validate the impugned legitimacy of the associated Nafanua religion and tradition. The Manono regime was blessed by Nafanua and Tamafaigā was her designated high priest. The manner of Tamafaigā’s assassination reflected on Nafanua religion, as was intended by the assassins and their supporters. The ferocity of the reprisals was accordingly deliberate and premeditated - it was meant to restore legitimacy to a religion whose mana was threatened by sacrilege committed against the person of the anointed.

The big issue after the war was power, not titles. The malo represented the party in power, and the malo was in Manono, not in Sapapalii. The dilemma facing the Malietoa party was how to wrest the malo from Manono without alienating Manono. The dilemma was illustrated by the Manono invitation to Malietoa to join them in Luatimu, the main malae in Manono, to deliberate on a successor to Tamafaigā. Malietoa declined by saying that there should not be another Tamafaigā. A second invitation, more imperious in tone, followed the refusal of the first invitation. Malietoa was invited to join the rest of the malo in paying tribute to the skull of Tamafaigā. Malietoa declined again on the ground that there was only one Lord - Jehovah, in Heaven. Manono felt insulted, declared war and appointed a special mission to assassinate Malietoa. Against the wishes of his sons, Malietoa made peace overtures and war was avoided.

John Williams in 1832 reported on the incident, having arrived three months after it happened. Williams paraphrased the reports of resident missionaries. Vaovasa, the designated head of the assassination squad, had killed a favourite daughter of Malietoa. Vaovasa had abducted the girl. John Williams writes:

The young girl would not accede to his wishes and all the people raised their voices against Vaovasa saying it was a bad thing in him to take so great a lady to wife, with this he took his club saying if he did not have her no one else should and struck her a blow on the head which split her skull in two and killed her instantaneously. Old Malietoa has never forgotten this. His sons also urged this upon him but he said he was determined if possible now he had become a Christian to end his days in peace.7

Instead of ifoga - the ritual pleading for pardon - Manono invited Malietoa to come to Manono and pay tribute to the skull of Tamafaiga. In pursuing their objective, the Malietoa party judiciously decided to avoid confrontation using other avenues, for example, advocacy of the London Missionary Society (LMS) missionaries, and the status of Tafa’ifa and the title Tonumaipe’a. Missionaries decided that the best attempts at central government could be made through a Malietoa; and therefore foreigners speaking on behalf of commerce, religion or governments were encouraged to parlay with the Sapapalii regime. In effect the malo in Manono should be bypassed.

Unable to wean the malo from Manono, and unwilling to fight for it, the Sapapalii regime indulged in gesture politics. They claimed the Tafa’ifa for Malietoa Vainuupo. Tafa’ifa symbolised the Salamasina inheritance and implicit in this inheritance is the claim to the malo. There was no attempt to establish this claim inside the relevant regions, Atua/Aana. If there had been, the missionaries assuredly would have reported on it. In its rivalry with Manono, the Sapapalii regime was consciously trying to establish credentials with foreigners who were already a factor and foreseeably an increasingly important one in the political equation. In contrast Manono’s focus was in seeking a successor to Tamafaigā.

The Sapapalii regime negotiated a marriage between Talavou, son of Malietoa Vainuupo, and a lady of Tamafaigā’s family in Manono. Through this marriage Talavou acquired the title Tonumaipe’a, at the instigation of Manono. Because Talavou resided in Sapapalii and later became Malietoa, Sapapalii claimed first call on the loyalty of the Tonumaipe’a people. Manono power-wielders were not unaware of the nuances of Sapapalii posturing. Whereas they were prepared to provoke a confrontation in the early 1830s, the military reverses in the late 1830s and throughout the 1840s caused them to be circumspect and less inclined to break the alliance. Manono was reduced to underlining a point by espousing a religion other than that of the LMS or provoking hostilities as a way of regaining waning power and prestige through prowess in war.

Notwithstanding severe military setbacks in the 1850s and 1860s and the shifting of the capital to Apia, Manono persevered in the belief that the malo remain in Manono. In 1889, whilst Malietoa Laupepa was in exile, Mataafa losefo was installed as Malietoa by the opponents of the Tamasese regime. Manono does not have an Ao or pāpā; the next best course was to make Mataafa their Tama Sa by naming him Tooā. Thus, the latter became Malietoa Tooā. By this gesture Manono was asserting its status as malo. After his defeat in Fale’ula in 1893 Mataafa retreated to Manono. Commentators mistake the move as seeking refuge. He was not. He was indulging in residence politics. He was flinging a challenge to his opponents: ‘I am Tooā Tama Sa of Manono, residing in Luatimu, the seat of the malo!’ The representatives of foreign powers read the situation correctly and sent warships to fetch Mataafa. Warships implied recognition that Mataafa was not an impotent refugee but a potential threat or menace.

Residence politics emanate from the cultural significance attached to residence. The essential attributes of a Samoan chief are among other things kava cup name, taupou, manaia, and residence. The site, stone formation and height of a house specify status. The residence name commemorates a landmark occasion in family history. The emblems of the family god and family icons, such as remains of ancestors and trophies of war, were buried under the principal pillar in the middle of the house. The ultimate punishment short of killing or execution is razing the residence - an act known as mu le foaga, literally ‘setting the nest afire’.

When therefore Mataafa losefo withdrew from Mulinuu in 1893 and set up house in the official residence of Malietoa in Malie, he was issuing a challenge: ‘I am Malietoa Tooā, residing in the official residence of Malietoa.’ Attempting mediation between the two parties was futile. Malietoa Laupepa’s claim to kingship was through the title Malietoa. In the context of faasamoa, Laupepa cannot be Malietoa while a claimant resides in the official residence of Malietoa.

The conclusions we can draw are these: the Tooa of Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi and the Tooā of Mataafa cannot be equated, and knowledge of genealogy is crucial in analysis. There are political nuances in a claim to a title and physical occupancy of a residence.

Generally, honours originate from a mavaega (last testament) or the patronage of a pāpā holder or a Malietoa. The custodians of these honours are Tumua and Pule. The beneficiary is required by custom to demonstrate appreciation by making a ritual presentation of fine mats, tapa, mats and food to the originator of the honours and to the village and district for recognising the honour in honorifics and in the hierarchy of titles. Honorifics can be equated to the College of Arms. They are, and have been, the standard test for claim and counterclaim.

According to one tradition (incidentally accepted by both Gilson and J W Davidson) Malietoa Vainuupo’s mavaega provided that the Tafa’ifa should die with him; the pāpā Tui Aana should go to Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi and the pāpā Tui Atua to Mataafa Fagamanu; the successor to the Malietoa title, Taimalelagi, Vainuupo’s brother, would become Tupu o Salafai and by implication heir to the Pāpā o Fafine, that is Gatoaitele and Vaetamasoalii.

There is actually no such title as Tupu o Salafai. The standard work on honorifics was written by the LMS, principal prop of the Malietoa party. In the Sapapalii honorifics the Tusi Faalupega refers to Malietoa: Susū mai lau susuga Malietoa na faalogo i ai Samoa (Greetings to His Highness Malietoa to whom Samoa listens) and refers to Feagaimaleata (Sapapalii) and Tualagi (Malie) as the residence of Malietoa. There is no mention of a Tupu o Salafai. References to the Malietoa title are similar in the Malie honorifics. Gilson claims that the first Tupu o Salafai was Tamafaigā. Neither in the Savaii nor in the Manono honorifics is there acknowledgement of a Tupu o Salafai. Every title, including the highest, possesses as of right certain attributes. A claim about the existence of a title lapses in the absence of these essential attributes.

What then does the Tupu o Salafai in the Vainuupo mavaega mean? Firstly, it represented a claim to Savaii overlordship. Secondly, to reinforce status, particularly for the perception of outsiders, there had to be a claim to be tupu insofar as the word equated with kingship.

In the Manono-instigated wars of the 1840s and early 1850s in which Malietoa Taimalelagi participated, most of Savaii were either opponents or, like Faasaleleaga, neutral. The claim to overlordship was sometimes no more than a claim. The claim to Savaii overlordship seemed to be premised on Safotulafai pre-eminence.

Davidson, who accepts it, says: ‘The orators of Safotulafai the political centre of Faasaleleaga and Sale’aula that of Gaga’emauga constituted Pule. The former of these groups was the more important and to some extent spoke for the whole of Savaii.’8 Yet the vaunted pre-eminence of Safotulafai is inconsistent with the dominance of the Tonumaipe’as from the Salamasina era up to Tamafaigā’s time. George Turner, one of the principal proponents of overlordship, attributed the political divisions of Savaii-Itu o Tane and Itu o Fafine to alleged bravery or cowardice of Savaii participants in the 1830s war.9 Davidson followed the Turner version: ‘In the 19th century the Itu o Taoa came to be called the Itu o Tane (side of men) and the Itu o Fafine (side of women) in reference to the alleged bravery and cowardice of the men of the two regimes, respectively, in a war against Aana in 1830.’10 The proposition becomes untenable once it is established that the Tamafaigā domain was mainly on the Itu o Fafine. The political division of Savaii precedes the 1830s’ war by centuries. The division into Itu o Tane and Itu o Fafine originates from a Uea initiative to seek marital alliances. The Tui Uea’s daughter could not find a husband on the eastern side of Savaii because eligible men were either married or betrothed. An eligible husband was found in the Aopo/Asau area. Hence the names Itu o Tane (side of men) and the Itu o Fafine (side of women - the eligible men were committed to women). The political division of Savaii integrates with early settlement of the island.11

If pre-European Samoan history was not written, it was nevertheless recorded by honorifics, words and names, or specifically their origin. Take Mata’utia Faatulou, meaning ‘Mata’utia, excuse me’. For political reasons Mata’utia’s sponsors Leifi and Tautolo eventually persuaded their reluctant ward to marry his high-ranking first cousin Levalasi. Mata’utia was reluctant because of the consanguinity tapu on marriage between children of brother and sister. Before indulging his husbandly duties he had to say tulou - ‘excuse me’ - because he was breaching the consanguinity tapu, thus becoming known as Mata’utia Faatulou. When Levalasi gave birth to a clot of blood, Leifi and Tautolo assumed a curse because of a breach of tapu. They determined to assassinate Mata’utia and replace him as husband of Levalasi with another suitor from Atua. They murdered Mata’utia and the aftermath was a cataclysmic change in the course of Atua history. Levalasi, who had come to love her husband, was inconsolable. Fearful of reprisals from Levalasi’s family, Atua built a pyre in which the two culprits Leifi and Tautolo were burnt alive. Satisfied by the taulaga (human offering) Levalasi’s brothers Tupa’i and Tauiliili did not exact reprisals; but Levalasi was returned to Leulumoega, where subsequently Salamasina became her adopted daughter and heir.

Another example is Laauli or Laailepouliuli, meaning ‘a step into the dark night’. In this case Gatoloai, daughter of Tunavaetele, became pregnant by her own brother ‘Alimanaia. To avoid public disgrace, the father offered his daughter in marriage to Malietoa Itualagi. Gatoloai bore a son by her brother and the child was named Laauli: ‘A step into the dark night’. Laauli was willed by Malietoa Itualagi to succeed him as Malietoa. Malietoa Laauli married Gauifaleai and produced Gatoaitele. Gatoaitele married Sanalala of Safata and sired Vaetamasoalii, Atogaugaaletuitoga and Lalovimamā. Atogaugaaletuitoga married Tonumaipe’a Sauoaiga and sired Tupa’i, Tauiliili and Levalasi. Because Malietoa Laauli sired only daughters, he adopted Falefatu who succeeded him. Gatoaitele quarrelled with Falefatu and insults were exchanged - the incestuous grandparents and the fact that Gatoaitele was not even an heir of Malietoa were all mentioned. The quarrel became the pretext for war.

Tuamasaga was divided. Malie led the Falefatu faction and Afega the Gatoaitele faction. Gatoaitele sought the assistance of her grandsons Tupa’i and Tauiliili to redeem family honour. Tupa’i and Tauiliili responded in the name of the war goddess Nafanua. Falefatu was defeated and by way of taking status away from Malietoa and Malie, the title Tupa’i was imposed on Tuana’i to underline suzerainty. The new pāpā Gatoaitele, named after the grandmother, was created in the name of Nafanua and presented to the latter’s keeping. The residence of the new pāpā was in Afega. Malie, the seat of Malietoa, and Afega, the seat of Gatoaitele, share the honours anomalously as Tumua - so that in honorifics you may refer to Lufilufi or Leulumoega (other Tumua) individually but protocol requires that you refer to both Afega and Malie as ‘Tuisamau and Auimatagi’. There is more than one version of the establishment of the pāpā Gatoaitele but the origin and meaning of the name Laauli is a key factor.

In Safata, a quarrel between Satunumafono and Lealataua over the distribution of fine mats became casus belli. Sanalala sought the assistance of his grandsons. Tupa’i and Tauiliili intervened in the name of Nafanua. Victorious, Tupa’i and Tauiliili imposed the title Tupa’i in Vaiee (Safata) as a symbol of their authority and created a new pāpā named after their aunt Vaetamasoalii. As instructed the pāpā was given over to Nafanua’s keeping. This was the peak point in the Nafanua-Tonumaipe’a ascendency. Victory in war denoted superiority in arms and, as an axiomatic corollary, superiority of the sponsoring god. Nafanua became the national goddess and Tonumaipe’a was her prophet. The Nafanua religion became so ingrained in the national psyche that from John Williams to the present day Christians deliberately integrate the Christian message with the Nafanua mythology.

Krämer says of Turner:

Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi was close to holding all four titles about the year 1869, as only part of Atua was loyal to Mataafa and part of Tuamasaga stood out. The position at that time is easy to understand, when one considers that in spite of Sualauvi and in spite of Tumua, the subsequent Malietoa Laupepa had been declared King on the 24th January 1868 through the influence of the missionary Turner and the English Consul.12

Krämer charged Turner with being a political partisan, but Krämer was a political partisan himself. Krämer was a highly competent ethnologist and his work is deservedly respected. Yet through the auspices of the German network in Samoa, he became committed to the Mataafa cause; he was given a brief to advocate this in the kingship court case in 1898. Thus notwithstanding its acknowledged merit, Krämer’s study is occasionally compromised. Two brief examples illustrate this.

In his genealogical table Krämer lists a separate and distinct Tui Atua line which ends with Mataafa Tupua.13 There is no justification for a separate Tui Atua line as distinct from the Salamasina Tui Aana line. Mataafa’s claim to pāpā honours is through Tupuivao and Tupua who are of the Salamasina Tui Aana line. At the peak of his career Mataafa Iosefo styled himself ‘Mataafa Tupua’, acknowledging thereby that his claim to kingship was through the Tupua connection. The separate Tui Atua line is a clear attempt to bolster Mataafa’s claim. In the absence of justification, this seems to be the inescapable conclusion. In this instance Krämer was more partisan than scholar.

Krämer frequently refers to Tui Atua Paitomaleifi and Tui Atua Mataafa Faasuamaleaui. In his genealogical tables and in other references, Nofoasaefa is listed as only Tui Aana. Yet in his outline of history at the beginning of the first volume Krämer says of the rivalry between Paitomaleifi and Mataafa, ‘Paitomaleifi seems to have been defeated in that struggle’, and then goes on to say ‘Nofoasaefa now took the field against the conqueror, Mataafa, in order to obtain the Tui Atua title’. He mentions the line up of support and battle and says ‘Mataafa was defeated and Nofoasaefa became Tui Atua’14. Again he was more partisan than scholar. And it is my impression that Gilson and Davidson, because they lacked the Samoan language and overlooked the relevance of genealogy, names and honorifics, were too dependent on political participants like Turner and Krämer.

In 1898, Faalata, son of Malietoa Talavou, was the claimant to the Malietoa title on the Mataafa side. Shortly after Mataafa withdrew his candidacy for kingship the Germans established their administration. Mataafa became Alii Sili and Faalata was recognised from 1900 until his death in 1910 as Malietoa by his peers, the German administration, genealogist W. von Bulow, and by the people generally. Malietoa Tanumafili returned to Samoa from Fiji following the death of Malietoa Faalata. Gilson and Davidson omit the ‘Malietoa’ when referring to Faalata.

In the struggle between Talavou and Moli/Laupepa neither Gilson nor Davidson mentions the main issue of contention. Malietoa Fitisemanu, sired by Fuatai, Taimalelagi who succeeded Malietoa Vainuupo. Malietoa Fitisemanu’s son (by a different lady) Malietoa Vainuupo sired Malietoa Talavou by the same Fuatai. Moli and later Laupepa’s supporters claimed that Talavou was ineligible because he was the issue of sopotofaga, meaning ‘intrusion into the royal bed’. The case against Talavou’s claim and later the latter’s son Faalata was based on the issue of sopotofaga.

Was the omission deliberate? If it was, I suspect it was motivated either by respect for the title or courtesy towards the current titleholder.

‘I’amafana was the King to whom gods and men rallied’ said Pratt. Krämer quoted Pratt’s high opinion in concurrence. Brother Henry claimed that I’amafana was the son of Galumalemana.15 The conventional view is so pat and unreal that a reanalysis is sorely needed in order to give us an insight into the long turmoil which came after I’amafana’s death.

King Galumalemana was well on in years and Nofoasaefa as alii o aiga (equivalent to dauphin) behaved as if he were king. He was ruthless, tyrannical and a cannibal. His enemies were determined to thwart his succession. They decided that a marital link with the powerful Tuimalealiifanos of Falelatai might help to attain their objective. Galumalemana gave his assent and the only other problem was, ‘Is the old man up to it?’ Sauimalae, the new wife’s first issue, was originally named ‘Ua’uapuaa and later Saipa’ia (now an Aloalii title in Satapuala): ‘Ua’uapuaa meaning ‘the pig hoeing into the ground making the noise ‘ua ‘ua’ and Saipa’ia meaning ‘ineligible to be anointed’. The origins are irrelevant to our present purposes.

Aware of his father’s inadequacy, Nofoasaefa decided to neutralise his enemies’ designs by taking to bed the father’s wife. It is permissible in custom for the son to substitute in the inadequacy of the father. For example, Aiolupo son of Lilomaiava substituted for his father to produce the famous Lilomaiava Tamaaleaitumaletagata. His name very tellingly means ‘the issue of the ghost and the mortal’. But it is permissible only with the consent of the father and the orators of Tumua. In the absence of that consent Nofoasaefa’s conduct was the grave breach known as sopotofaga: intrusion into the royal bed. Sauimalae became pregnant and when asked by whom, responded ‘O tae lava o le alii’; ‘It is by shit of the royal personage’ - and hence the name of the founder of the aloalii title of Si’upapa, Lepa, Taeoali’i.

Nofoasaefa’s enemies worked on the king emphasising the breach of tapu and the gratuitous insult to the father. Sauimalae became pregnant for the third time. Coinciding with her third pregnancy was the mavaega of the dying Galumalemana. Nofoasaefa’s enemies knew they could not derail the Nofoasaefa bandwagon and as a last resort persuaded the king to reciprocate perversity with perversity by putting a blight on Nofoasaefa’s right to succeed by designating the child in Sauimalae’s womb (who was after all Nofoasaefa’s son) as the successor. As expected the designation could not be implemented at the king’s death and Nofoasaefa succeeded by Tumua’s designation (saesae laufa’i) and common consent of aloalii (lalagofaatasi). Lalagofaatasi, meaning ‘common consent’, became Sa Tupua’s cup name. The union between Nofoasaefa and Sauimalae was formalised. Shortly afterwards a son was born. When the boy was presented to Nofoasaefa, he said, ‘He is born after our union is formalised and therefore he is not ulu ‘ela’elā’; meaning, literally, ‘A fishy smelling substance in the head’, which according to Samoan belief identified the bastard - but an i’a mafanafana (warm fish freshly cooked) i.e., he is legitimate. Hence his name I’amafanafana, shortened to I’amafana.

After Nofoasaefa’s death, I’amafana’s candidacy for kingship was opposed by Tupolesava, whose candidacy was supported by Tualamasalā, both halfbrothers of Nofoasaefa. Despite Galumalemana’s designation, Tupolesava claimed that I’amafana should not succeed because he was illegitimate and an issue of sopotofaga. Because I’amafana won and was much loved there was a public relations campaign to camouflage the details of his origin.

Lufilufi and Leulumoega were at loggerheads on the issue of successor to I’amafana on the decease of the latter. Lufilufi pre-empted further discussion by withdrawing to Atua and conferring the Tui Atua title on Safeofafine, the alleged son of I’amafana. Leulumoega was aggrieved on two counts. Safeofafine was not, according to Leulumoega, a son of I’amafana, thus his name. Acquisition of Tafa’ifa was traditionally initiated by Leulumoega conferring the Tui Aana and climaxed by Lufilufi conferring the Tui Atua. The argument deteriorated into a long, destructive armed struggle, culminating in the defeat and death of Safeofafine at a critical battle on the Aana/Tuamasaga boundary.

Claimants to the Tafa’ifa title gave their support to one party or another on the understanding that their claims were thereby improved by favourable fortune in war. The division within the ranks of the ancien régime and the resultant chaos and confusion provided Manono and Tamafaigā with the opening to exploit a weakened and vulnerable opponent. The threads then which link I’amafana’s alleged last testament and Malietoa Vainuupo would have to weave through thirty years (1800-1830) of constant warfare and the varying fortunes of about four or five claimants to Tafa’ifa. The conventional view of I’amafana’s last testament must be exposed to objective historical analysis to determine what is sustainable by the evidence and what is mythology concocted to promote a particular political purpose.

The biggest riddle, speaking as a Samoan, is within ourselves. Can or should we tell all we know about Samoan history and culture for general historical examination? The missionaries have imposed a Victorian prudishness on the national psyche to the extent that we have acquired a colossal hang-up about ourselves and our culture. We have succumbed to a sanitised version of Samoan history, whether alien or indigenously authored, because it portrays an idealised Samoa. There is a strong sentiment about defending this idealisation. There is an awful fear that if all is told, the Palagi will think less of us. Hence the penchant to camouflage, condense and edit.

Our funeral rites are now a caricature of the original because of a fear of straying from an alien ethos. There is no Garden of Eden, a fall and redemption in traditional Samoan religious belief. Life is a journey towards Pulotu and a struggle against the gods. In our traditional funeral rites we do not mourn death, we celebrate life. We chant about our victories against the gods - nothing deferential or mea culpa-like. Tattooed men are already dressed, according to our beliefs. The tattoo and ritual are focused on the private parts of men. We flaunt in ritual our power to procreate. The gods have taken one, but so long as we can reproduce we triumph. It is roughly the equivalent of the Christian challenge ‘Death, where is thy sting?’ but perhaps more convincing.

Some of the loveliest poetry and the most powerful imagery in the Samoan language are contained in the marriage and consummation chants that have been relegated to the closet by missionary bias. Pratt was sufficiently impressed to translate some into Latin. Sadly, these chants are still very much in the closet although the missionaries can hardly be blamed for this. A pity because the marriage (tini) and the consummation (fisi) chants and the funeral rites are some of the most reliable records of our cultural history.

I am breaking tapu for two reasons. Firstly, sanitisation of the myths, claims and counter-claims needs exposure to sunlight and clean air. Secondly, as Samoans we should not be embarrassed about our ancestors or apologetic about Samoan history and culture. The warts and lows in Samoan history, real or so-called, are explicably human. How then can we homines sapientes, not specifically Samoans, begin to cope with the riddle or riddles in Samoan history? First, foremost and last by recognising:

1. That Turner was a political partisan as are the Malietoas.

2. That Krämer was a political partisan as are the Mataafas.

3. That Robert Louis Stevenson was a political partisan as are the Tuimalealiifanos.

4. That Tupua Tamasese is a political partisan whether or not he is conscious of it.

For indeed we have to be sceptical about our own as well as other people’s work.

In criticising Gilson and Davidson, I can’t resist asking myself, ‘Am I debunking for its own sake? In the inner recesses of my mind is there lurking a hang-up I am not readily conscious of?’ In the search for perspective and balance I remind myself of Tennessee Williams’s lines:

We are the geeks and gooks of creation;

Believe-It-or-Not is the name of our star.

Each of us here thinks the other is queer

And no one’s mistaken since all of us are.16

1. Explanatory Gafa

1. Selaginato m. Vaetamasoa

Tui Aana Tamalelagi

2. Tonumaipea Sauoaiga m. Atogaugaletuitoga

Tupa’i - Tauiliili - Levalasi

3. Lalovimamā m. Tui Atua Sefaatauemana

Mata’utia m. Levalasi

2. Tuimalealiifano Sualauvi - Gafa

| Fofoaivaoese | Tapusatele |

| | | | |

| Taufau | Tapufautua |

| | | | |

| Faumuina | Sifuiva |

| | | | |

| Fonoti | Fuimaono |

| | | | |

| Muagututi’a | Tupua |

| Tamasese Line | Mataafa Line |

| | | | |

| Tupua | Tupua |

| | | | |

| Galumalemana | Luafalemana |

| | | | |

| Nofoasaefa | Salainaaloa |

| | | | |

| Maeaeafe Mataafa | Faasuamaleaui |

| | | | |

| Moegagogo | Mataafa Filisounuu |

| | | | |

| Tamasese Titimaea | Mataafa Fagamanu |

| | | | |

| Tamasese Lealofi | Mataafa Iosefo |

1The article was originally published in The Journal of Pacific History 29(1) (1994) pp. 66-79. This chapter contains minor revisions by Tui Atua.

2R. P. Gilson, Samoa 1830-1900: The politics of a multi-cultural community (Melbourne 1970), 59.

3ibid. 60.

4ibid. 117 fn 5.

5ibid. 70.

6Richard M. Moyle (ed.), The Samoan Journals of John Williams 1830 and 1832 (Canberra 1984), 2.

7ibid. 2.

8J. W. Davidson, Samoa mo Samoa (Melbourne 1967), 27 fn. 9.

9George Turner, Samoa a hundred years ago and long before (London 1884), 255.

10Davidson, Samoa, 27 fn.

11Gatoloai Faana Peseta S Sio, Tapasa o Folauga i aso afa: Compass of sailing in storm (Apia 1984), 99.

12The 1991 edition of Augustin Krämer’s The Samoa Islands cited by the Journal of Pacific History as the source for this quote was at the time of the republication of this article as a chapter for this book no longer in print. The same quote -although slightly paraphrased -is to be found, however, in the later republication of Augustin Krämer’s The Samoa Islands. This is to be found at: Krämer, A., The Samoa Islands (Translated by Dr. Theodore Verhaaren) Vol I. Auckland: Polynesian Press, 1994, p. 275.

13Augustin Krämer, The Samoa Islands (Engl. trans., Utah 1991), I, 934.

14ibid. 391.

15Krämer, Samoa Islands, 392; Br Henry, History of Samoa (rev. ed. Apia 1979), 121.

16Williams, T. 2002. “Carousel Tune”, In The Collected Poems of Tennessee Williams. Roessel, D. and Moschovakis, N. (Eds.). New York: New Directions Books. p. 60.