5: TRAINING DESIGN: OBJECTIVES & CONTENT

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the main components of the training design process

- List the types of questions you should ask when designing a learning event

- Describe the reasons for setting smart learning objectives and identify the characteristics and benefits of well-written learning objectives

- Describe the different types of learning objectives that are appropriate

- Describe some of the “rules” that you should follow when developing training course content

- List the rules that should be followed when sequencing training content.

INTRODUCTION

We considered the training needs analysis process in Chapter Four. In this chapter, we move on from the needs analysis process to consider how these needs translate into learning objectives and learning content. We focus on two elements of the training design process in this chapter:

- The formulation of learning objectives

- How these learning objectives translate into content.

We also integrate key principles about how people learn as part of the design process. You can refer back to Chapter Three to refresh your memory on adult learning principles and theories.

The training design phase is concerned with preparing the blueprint for a training programme or intervention. In your real work experience, you will be asked to plan and design training activities that range from straightforward to highly complex – for example, the task could involve anything from the design of an on-the-job training activity to the design of a complex management development programme. The key decisions are essentially the same irrespective of the complexity involved. It is critical that you are clear about the key learning objectives, the content and structure of the training event that you propose to run.

COMPONENTS OF THE TRAINING DESIGN PROCESS

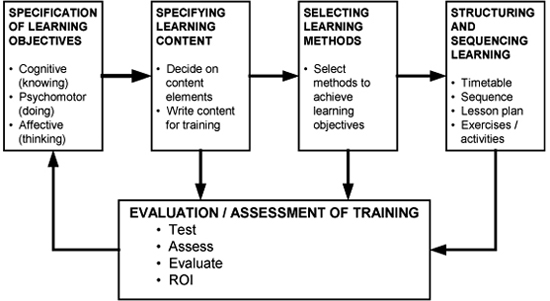

We suggest that the overall training design process can be represented in the following sequence of activities:

- Specifying learning objectives

- Specifying learning content

- Selecting learning methods

- Structuring and sequencing the training programme.

These activities fall within the systematic training model. Systematic training can be defined as “training specifically designed to meet defined needs”. It is planned and provided by people who know how to train and the impact of the training is carefully evaluated. A systematic model, however, is based on the premise that training and development is the appropriate course of action. Figure 5.1 presents an outline of the components of a systematic approach to training design.

FIGURE 5.1: COMPONENTS OF T&D PROCESS

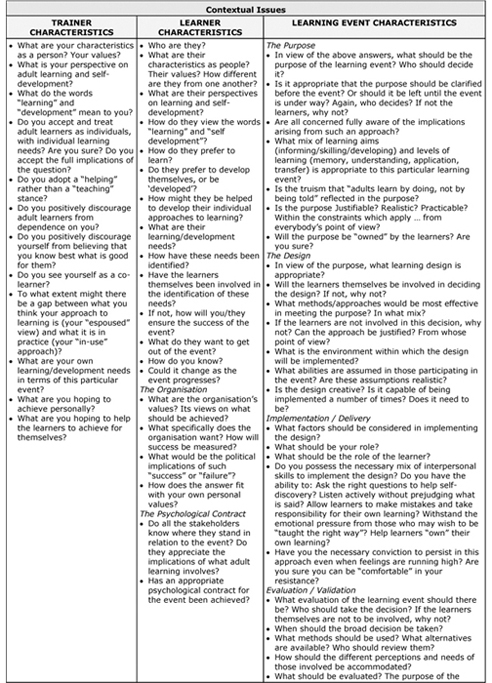

You should remember that the design of training activities is not an exact science, but involves judgement and intuition and a certain amount of “trial and error”. Figure 5.2 presents a checklist of questions that you should consider when designing a training event.

FIGURE 5.2: CHECKLIST FOR DESIGNING A TRAINING EVENT

LEARNING OBJECTIVES: PURPOSES & CHARACTERISTICS

We have already emphasised that the process of setting learning objectives is an important part of training design.

Learning objectives serve three main purposes:

- Define the desired learning outcomes that you can expect to achieve your training event

- Provide guidelines for the design of the training programme and help you with the selection of learning methods and activities

- Provide you with criteria to enable you to evaluate the training activity.

Learning objectives provide a critical link between the identification of learning needs and the actual design and delivery of learning. Well-written learning objectives should possess the following characteristics:

- They should be as clear as possible, ideally indicating the specific behaviours to be achieved

- They should be as quantifiable as possible

- They should be achievable within the time scale specified for the training.

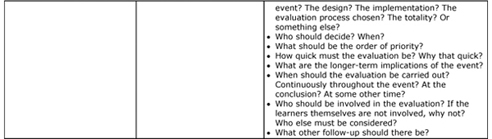

Most trainers agree on the value of setting learning objectives, although there are dissenting views. Some trainers find that rigorous objective setting makes the learning activity “too cold and clinical”, whereas others point to difficulties in composing objectives, especially those reflecting attitudinal learning outcomes.

Turning needs statements into learning objectives is not always an easy task. It is relatively simple to write tangible objectives from statements in the psychomotor (skills) areas, but much more difficult when you are focusing on knowledge, attitudes and longer-term training needs.

We summarise some of the benefits and difficulties associated with setting learning objectives in Figure 5.3.

FIGURE 5.3: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF SETTING LEARNING OBJECTIVES

COMPONENTS OF A LEARNING OBJECTIVE

There are three main components to a learning objective, which can be summarised as:

- The required performance or action that the learners are expected to display at the end of the programme

- The standards that the learners are expected to reach

- The conditions under which they are to perform.

The following are examples of learning objectives that reflect the three components:

Knowledge Objectives |

Skill Objectives |

Affective Objectives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5.4 identifies a number of questions that you should consider to guide your analysis of a learning objective to determine its level of acceptability. A No answer to any question will pinpoint a characteristic that is missing or ambiguously stated. Clarity is judged by whether or not another person’s restatement of the objectives is consistent with your intent.

FIGURE 5.4: QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER WHEN SETTING LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1.Is it clear WHO will be performing the action?

It is not always necessary to state the “who” explicitly (the learner, the student, the trainee), unless there is potential for confusion about who is performing the action. Objectives should be written in terms of the performance outcomes you expect of the learner.

2.Is it clear WHAT the learner will be doing? Is the behaviour observable and/or measurable?

3.Is it clear UNDER WHAT CONDITIONS the learner will be performing?

There are two dimensions to this characteristic:

a) it may be appropriate to specify what the learner will be provided with during the learning event

b) it may be appropriate to describe the situation in which you expect the behaviour to occur (when conducting a CAA board meeting …; when confronted by an irate customer ...; when preparing to submit a proposal).

4.Is it clear WHAT LEVEL OF PROFICIENCY OR COMPETENCY is expected?

This may be stated in such terms as a number of percentage of correct test items, a change in score on an attitude inventory, execution of a process according to a prescribed sequence or other criteria. If time is a factor in successful performance, that may be specified as well.

5.Is it clear WHEN this behaviour is expected to be demonstrated?

This characteristic is usually stated in terms of the length of the instructional experience (at the end of a session, at the end of a week, after a certain number of practice sessions).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES: CLASSIFICATIONS & TYPOLOGIES

We will consider three models or frameworks that you can use when preparing training objectives. These hypotheses are theoretical, although they have useful application to the training area.

Bloom’s Typology of Learning

Bloom (1976) developed a categorisation of cognitive or knowledge capacities that is of considerable value to a trainer. This model has a number of benefits; in particular, it suggests a hierarchy that can be relatively easily applied to a range of training situations that you are likely to encounter.

Bloom makes three major divisions of learning objective, each called a “domain”:

- The cognitive – information and knowledge

- The affective – attitudes, emotions and values.

- The psychomotor – muscular and motor skills, but not interpersonal skills.

The Cognitive Domain (Knowledge)

This domain is based on a hierarchy ranging from mere knowledge of facts to the intellectual process of evaluation. Each category within the domain is assumed to include behaviour at the lower levels:

- Knowledge: This is based on recall and on the means of dealing with recalled information. It comprises:

- Knowledge of specifics (terminology and specific facts)

- Knowledge of ways and means of dealing with specifics (conventions, trends and sequences, classifications and categories, criteria and methodology)

- Knowledge of the universals and abstractions in a field (principles and generalisations, theories and structures)

- Comprehension: This is the ability to grasp and utilise the meaning of material. It embraces “translation” from one form to another (words to numbers), interpretation (explaining, summarising), and extrapolation (predicting effects, consequences)

- Application: This involves the ability to use learned material in new situations. It necessitates the application of principles, theories, rules etc.

- Analysis: This involves the ability to break down learned material into component parts so that the internal structure is made clear. The analysis of relationships and the identification of the parts of a whole are vital

- Synthesis: This refers to the ability to combine separate elements so as to form “a new whole”. Deduction and other aspects of logical thought are involved

- Evaluation: This concerns the ability to judge the value of material, with such judgements based on definite criteria or standards.

The Affective Domain (Attitudes and Values)

This domain is “attitudinal” in focus and ranges very widely, from heeding the simple reception of stimuli to the complex ability to characterise or value concepts. Many training activities that you will be asked to design focus on changing attitudes. Examples include developing positive attitudes to customer service, quality and health and safety. Bloom suggests that there are five major categories of attitude objectives:

- Receiving: This involves the trainer “attending” to, or heeding, messages or other stimuli. Awareness, willingness to attend and controlled attention are included here

- Responding: This involves the arousal of curiosity and the acceptance of responsibility in relation to a response

- Valuing: This involves recognition of the intrinsic worth of a situation so that motivation is heightened and beliefs emerge

- Organising and Conceptualising: This involves the patterning of responses on the basis of investigation of attitudes and values, and also the beginning of the building of an internally-consistent value system

- Characterising by value or value concept: This involves the ability to see, as a coherent whole matters involving ideas, attitudes and beliefs.

The Psychomotor Domain (Skills)

Bloom also indicated a skill category, although it is very narrowly-focused on the development of motor skills:

- Reflex Movements: He defined these as involuntary motor responses to stimuli. They are the basis for all types of behaviour involving bodily movement

- Basic Fundamental Movements: These are inherent movement patterns, built upon simple reflex movements

- Perceptual Abilities: These assist learners to interpret stimuli so that they can adjust to their environment and are the essential foundation for skilled movement. Visual and auditory discrimination are examples

- Physical Abilities: These are the essential foundation for skilled performance. Speed, exertion and flexibility are examples that are of relevance in operator skills and computer skills

- Skilled Movements: These are the components of any efficiently performed, complex movement. They cannot be acquired without learning and require lots of practice

- Non-Discursive Communication: This comprises the advanced behaviours involved in the type of communication relating to movement, such as ballet. Movement becomes aesthetic and creative at this level of the domain. This is rarely relevant in the training context.

Some researchers have built on Bloom’s ideas and put forward more development-type categorisation – for example, Simpson proposes an alternative classification of psychomotor objectives. He suggests that there are seven categories of psychomotor objective:

- Perception: This involves the use of the learner’s sense organs in order to obtain those cues essential for the guidance of motor activity – sensory stimulation, cue selection and translation (of sensory cases into a motor activity)

- Set: The state of readiness for the performance of a certain action – mental, physical and emotional states

- Guided Response: This necessitates performance under the general guidance of an optimal performance model and involves imitation, trial and error

- Mechanism: The ability to perform a task repeatedly with an acceptable degree of proficiency

- Complex, Overt Response: The performance of a task with a high degree of proficiency

- Adaptation: The use of previously-acquired skills so as to perform novel tasks

- Origination: The creation of a new style of performing a task after the development of skills.

Rackham and Morgan (1997) provide a very useful classification of interpersonal skills that can be used by the trainer to write interpersonal skill learning objectives:

- Seeking/Giving Information: Asking for/offering facts, opinions, or clarification from/to another individual or individuals (you ask your supervisor about the meaning of a new work rule)

- Proposing: Putting forward a new concept, suggestion, or course of action (you make a job enrichment suggestion to your supervisor)

- Building and Supporting: Extending, developing, enhancing another person’s proposal or concept (in a departmental meeting, you suggest an amendment to someone’s motion)

- Shutting Out/Bringing In: Excluding/involving another group member from/into a conversation or discussion (in a departmental meeting, you ask a quiet member to give his/her ideas)

- Disagreeing: Providing a conscious, direct declaration of a difference of opinion, or a criticism of another person’s concepts

- Summarising: Restating in a compact form the content of previous discussions or considerations (before giving your comments in a departmental meeting, you summarise the arguments that have been presented).

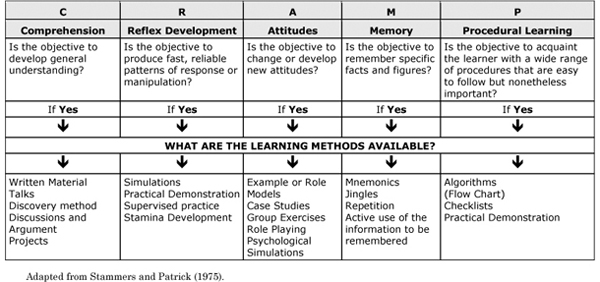

THE CRAMP MODEL

Stammers and Patrick (1995) suggest a model of learning objectives, which they call the CRAMP model. They identify five components to the model:

- Comprehension: The development of general understanding (Bloom’s cognitive domain)

- Reflex Development: The production of fast, reliable patterns of response or manipulation (Bloom’s psychomotor domain)

- Attitudes: The changing or development of new attitudes (Bloom’s affective domain)

- Memory: The recall of specific facts and figures (Level 1 of Bloom’s cognitive domain)

- Procedural Learning: Acquainting the learner with procedures that are easy to follow (Level 2 of Bloom’s cognitive domain).

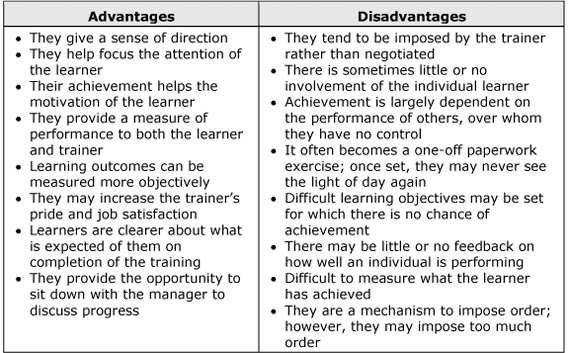

CRAMP is a very useful model, because it specifies the methods that are most appropriate for each type of objective. For example, if the objective is comprehension, then it is appropriate to use projects, written materials, talks, manuals, discussion and argument. If the objective relates to attitudes, then the trainer should use role-plays, psychological simulations, group exercises, case incidents, scenarios and role models. Figure 5.5 provides an illustration of this matching process.

FIGURE 5.5: THE CRAMP MODEL & LEARNING METHODS

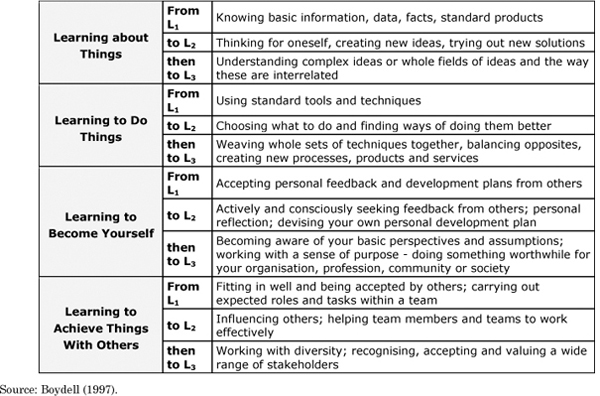

BOYDELL’S MODEL OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Boydell (1997) takes an alternative approach, suggesting that the trainer needs to consider both the type of learning and the level of learning.

Types of Learning

Learning About Things

Learning about things is broadly speaking about “knowing”. This covers a broad spectrum of knowledge and understanding, including memorising or being aware of basic information, data, facts, existing explanations, rules and standard procedures. At a deeper level of learning about things, it encompasses the following:

- The ability to think for yourself

- To create new ideas

- To create possible new solutions to “problems”

- To use questioning and insight to create new solutions where none currently exist

- Thinking things through, collecting and analysing data, drawing conclusions, are all part of this level of knowing about things.

Deeper still is the ability to understand whole fields of ideas and the way these are interrelated, by having a holistic overview of the way different sets of information or ideas are connected together. A specific example here is the ability to see how the various functions and departments of your organisation are part of a larger whole, and how are they all interdependent.

Learning to Do Things

“Learning to do things” is concerned with skills and techniques that can be used to facilitate management, control processes, enhance productivity and quality and thus improve customer satisfaction and increase profitability or value for money when using public funds.

This type of learning involves dealing with relatively standard, routine “programmed” tasks, by selecting and applying the appropriate technique. All organisations have many standard processes that are often written down in various procedure manuals.

However, “doing things” gets more complex when tackling “problems”. Faced with a variety of techniques, you have to know which are appropriate for your particular situation, and to what extent it or they will need modifying to suit your own unique circumstances. This involves, for example, decision-making, processing information, evaluating alternatives, choosing solutions and allocating responsibility for implementation. Doing these sorts of things requires initiative and the courage to step into the unknown and to take risks when the outcomes are uncertain. This is very different from simply following standard procedures.

A further level of complexity arises when you need to weave whole sets of techniques together, so that they become interconnected and co-ordinated, thus creating new processes, products and services. Doing this requires competencies such as organising, co-ordinating, mental resilience and the ability to cope with uncertainty, to balance the requirements of competing alternatives, to see things in terms of “both this and that”, rather than the relatively simple terms of “either this or that”. For example, a successful manager has to be able to learn both to lead and to hold themselves in the background, both to be dynamic and be reflective, both to be confident and to be humble, both to be able to keep a close relationship with their staff and to keep a suitable distance.

Learning to Become Yourself

As well as “learning to do things”, managing requires us to “learn to be”. It can be described as becoming yourself, to develop your own unique style of managing and to achieve your full potential. It is therefore important to develop the ability to assess yourself, so that you can identify your strengths and under-utilised opportunities, as well as aspects that need to be strengthened and developed further. A basic requirement is to learn to accept feedback from others and to see how this can form the basis of a personal development plan.

As you develop further, you don’t just wait for feedback but seek it actively and consciously, both from others and by reflecting on your own behaviour, thoughts, feelings and your intentions. From this, you can prepare your own development plan.

Gradually, this will increase your self-confidence, your awareness and your realistic appreciation of your own abilities. This will also enable you to re-examine critically your value system and draw conclusion(s) for yourself, to judge critically your own motivation, work habits and ethical values. Once we become conscious of our own deep values, beliefs and assumptions, we can also become aware of what we really want to achieve in life. We get a feeling for what our sense of purpose is and do something worthwhile not only for ourselves but also for our organisation, profession, community or society.

Learning to Achieve Things with Others

The fourth type of learning is “learning to achieve things with others”, which is where outcomes cannot be fully measured in terms of what individuals “take away”, but rather by what is created together. Team-working is a good example here, as carrying out your excepted role within a team requires teamwork and co-operation with other team members. It also requires using your best abilities in meetings, workshops and so on.

As well as team-working, another example is managers who, with increasing experience, need to be able to help other members perform to the best of their ability, thus showing leadership by inspiring and leading others. This way of working calls for the ability to work with diversity – working with people whose backgrounds, values, beliefs, skills, attitudes, language, customs, norms are different from ours. Therefore, learners need tolerance and respect for different personalities, cultures and opinions, and the ability to cohabit and co-operate in heterogeneous national, ethnic and cultural environments.

In fact this can be quite difficult – for example, engineers see personnel specialists as soft and out of touch with “real” issues. Personnel specialists on the other hand, see engineers as narrow-minded and mechanistic. Whether we are in finance, marketing, sales, public relations, research and development, we tend to see ourselves as “normal” and to have negative stereotypes about others.

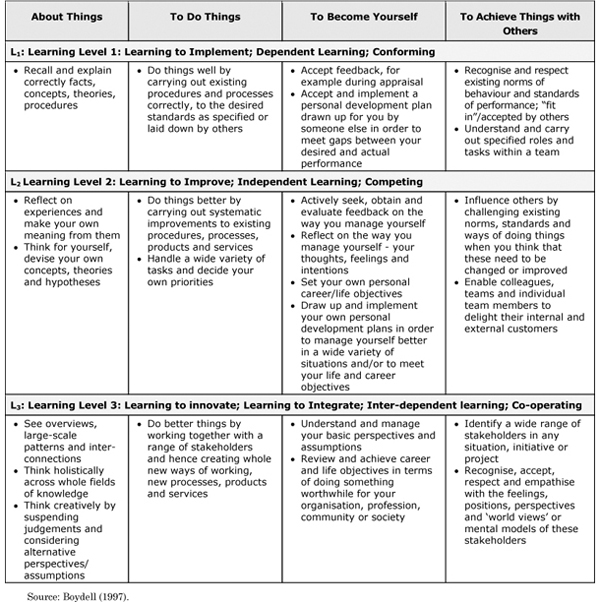

Levels of Learning

Each of the four types of learning progresses through three levels, starting from being relatively simple and gradually deepening and becoming more complex. We call these Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 learning, or simply Levels L1, L2 and L3.

Level 1 (L1) is about getting things “right”, according to currently accepted ideas, procedures, norms, etc. At its best, this level enables you to perform, to do things well, and to meet current accepted standards. These standards usually come from outside, from someone else other than yourself, such as your boss or an expert, or already accepted procedures.

At Level 2 (L2), you are now thinking and acting for yourself. This requires a much more independent form of learning than L1. Being taught (the essence of L1 learning) is not appropriate here. We need to use processes that involve you, the learner, in thinking for yourself, making your own meaning from your own experiences, of the situations you find yourself in, or the puzzles with which you are grappling. Therefore, learning is less off-the-job and more on-the-job, using the very issues that you are concerned with as the vehicles for learning.

Level L2 moves us on from implementing into improving and pushing out the frontiers of what we do already. It is an incremental approach, involving a wide range of gradual, partial and incremental changes. Where more radical changes are involved, we need a third type of learning: (Level 3 – L3).

FIGURE 5.6: LEVELS OF LEARNING

Large-scale change, by its very nature, involves large numbers of people such as a wide range of stakeholders who, as the word indicates, have a “stake” or interest in the organisation and its changes. Levels L1 and L2 learning cannot on their own handle this type of situation. It is not possible to manage large-scale change through using a standard formula or recipe (L1). Such situations are far too complex for simplistic approaches. Neither will the continuous improvement approaches of L2 be adequate here. The essence of this level of learning is to make incremental improvements to what already exists, rather than creating something new, which is what L3 is about. We therefore sometimes refer to this third level as innovating. In this way, we go from learning to do things better (L2) to learning to do better things (L3).

Level L3 is often also called integrating, because you need to be able to connect together different sets of ideas, perspectives, processes and people. You are moving from the somewhat individualistic stance of independence in L2 to one of interdependence and of being mutually connected and supportive. This level of learning therefore needs to go beyond “thinking for myself” to ways of working together and “thinking with each other”.

Figure 5.7 provides a summary of the types and levels of learning.

FIGURE 5.7: DOMAINS & LEVELS OF LEARNING

WRITING LEARNING OBJECTIVES

In order for learning objectives to be effective, they must satisfy certain criteria. In particular, they should:

- Be realistic: The objectives that are set must be attainable. They must not be so straightforward that there is no element of challenge nor so overwhelming that their achievement seems hopeless to the learner

- Be relevant: If the objectives are to have any meaning, they must be seen to have direct relevance to the job or personal situation. This can mean either that they will have an impact on work performance now or in the future, or that they will have some influence on the learner’s personal development

- Be positive: If objectives are to have direct relevance, they must also be of benefit to the individual. Consequently, objectives are drafted to provide a positive outcome rather than stipulating what a learner will no longer do as a result of attending a programme

- Be certain: Vague objectives are not objectives. Objectives should clearly specify who will achieve what, by when and under what circumstances. They should also state how success will be measured and any cost or time constraints involved

- Be justifiable: No matter how laudable the learning objectives of a programme are, the true measure of their success is seen by organisations in financial terms. Unless it can be demonstrated that the organisation will receive some return on its investment in the training, the programme may be considered as an unnecessary drain on resources

- Have a learning focus: Objectives relate to the knowledge, skills and attitudes that the organisation wants to enhance

- Be brief: Minimise the objective to a single sentence that is precise and limited

- Use action verbs: Use action verbs that allow for easy measurement and observation

- Be capable of evaluation: Objectives should provide a way to measure success by building in a standard of expected performance

- Guide content: Objectives should help the trainer concentrate on most relevant themes when preparing content.

DEVELOPING TRAINING CONTENT

The learning objectives you set determine the content you will include in your training programme. The trainer can often identify content that is related to the learning objective but not essential to it. Content should be assessed in terms of what must be learned to achieve the objective. The trainer needs to prioritise and determine what should be included and what could be included.

Working Out Content

In the absence of a job analysis and information on training needs, there are two techniques that can help the trainer to work out course content. Both are equally useful and it is usually a question of using the technique that feels most comfortable. However, we point out that a proper and systematic training needs analysis is a core component of the systematic training process.

Learning Maps

Learning maps (sometimes referred to as “mind-maps”) are an effective and easy way to assemble information about a subject. The difficulty in trying to collect information is that we tend to try and put it all down in a logical step-by-step format but continually have to revise it as new elements and ideas spring to mind. Learning maps recognise that learners do not think in logical steps, that there is often a constant stream of unconnected bits of information flowing from learners’ minds and that the trainer should capture it in that format. This can be facilitated in the following way:

- Start by drawing a picture, word or phrase at the centre of a page to stand for the topic

- Take the main ideas associated with the subject as they occur to you and let them branch out from the central idea. Express these branches as key words, pictures or symbols. Build up the overall “map” as thoughts occur with sub-branches coming out of main branches. This process more accurately reflects how we think and does not seek to funnel ideas into a logical, step-by-step sequence

- Draw connections between areas with lines or arrows. Use colour, if possible, to create a visual impact.

You may want to re-draw the map later; this is okay and helps it lodge in your memory. The map should represent the sum of knowledge, thoughts and ideas about the subject and can be added to or developed at a later stage without any difficulty. Because of the visual nature of the map, it is much easier to see connections between ideas or spot areas that are in need of development.

Horizontal Plan

As the name suggests, this process seeks to lay out the content of the training in a highly visual manner but with a potential flow built-in. The idea is to identify the headings and sub-headings of the subject and build the content around this plan. This process again makes use of the random thought patterns that occur when developing training material. One very simple and practical way of doing this is:

- Use “Post-it” notes to capture the key words or phrases that describe a section of content and stick them to the wall. Continue this process, until you have identified a large number of items

- Start to move them around, grouping them into related subject areas. Lay the groups together left to right in a line

- Identify subject headings for each group of notes and write that on a note above the group

- Start to shape the flow of the material by moving groups/subject areas around.

Again, this is quite a visual way of representing the sum total of information on a subject. It is also flexible and adaptable.

Sequence and Timing of Training Content

Once you have decided on the content that is appropriate to achieving your learning objectives, the next decisions you have to make are:

- What is the sequence of the content?

- What time should be allocated to each component of content?

Training content is usually sequenced in a logical order to reflect the training needs. Learning order is an important issue. Learning one task may be impossible or difficult until another is learned. Learning one task before another, even though not required, may facilitate learning the second task. Learning two tasks or content areas together may be feasible.

Sequencing is a necessary activity. Some tasks may have to be scheduled in a particular order. Others may prove helpful if scheduled in a particular order. Other areas of content may be scheduled in any order without consequence to themselves or to remaining tasks/content areas. You will be guided in making sequencing decisions from the results of your training needs and task analysis outputs.

You may find a number of patterns:

- Some areas of content/tasks may be subordinate to others. Some tasks may be subordinate to several others. Some may be neither but simply follow one another in performance

- In some situations, it may be appropriate to schedule subordinate content or tasks first because they are considered prerequisites. In other situations, subordinate tasks are scheduled first because that sequence will facilitate the learning process

- Tasks performed early are scheduled to be learned early, whereas the alternative is that tasks performed late are scheduled to be learned early

- The performance sequence and learning sequence may differ. Sequencing is more likely to be effective, the more accurately you have identified prerequisite issues and content/task relationships.

Figure 5.8 summarises a number of guidelines and principles that you should follow when sequencing training content.

FIGURE 5.8: GUIDELINES FOR SEQUENCING THE CONTENT OF YOUR TRAINING PROGRAMME

- Consider the need to get the attention of the trainees. Trainees learn only when they pay attention to training. Their motivation stems from some benefit or value on the training. This has implications for initial training content.

- Trainees only believe, listen to and learn from materials that they consider being influential or credible. Materials are influential/credible if they are based on expertise and are attractive to trainees.

- Trainees learn most easily when the training content is put in a context of something they already know and is taught using familiar concepts and terminology.

- Trainees learn best, when, in addition to having ‘hooks’ for the training content, they have a mental set or posture of the overall content before they go into details. Trainees receive a mental picture when provided with an overall structure of the new information at the beginning of the training.

- Trainees can perceive only limited amounts of information at one time. Research generally reveals this capacity to be seven meaningful pieces of information, plus or minus two pieces.

- Trainees can perceive and remember longer amounts of information if the information is grouped or chunked.

- It is prudent to start from existing knowledge, skill and attitude.

- If trainers have limited experience of training, then it is appropriate to place easily learned tasks early in the learning event.

- Trainees learn better from training materials that combine text and illustrations. Word messages can be enhanced or made more understandable by the use of illustration.

- Trainees learn ideas better when they are presented with examples of those ideas.

- Content sequence can be organised in the following ways; known-unknown, concrete -abstract, general, particular observation – theory - reasoning, simple – complex, overview – detailed.

- Introduce broad concepts and technical terms that have relevance throughout the training, early on in a programme.

- Continuity of content is generally more effective than a series of unconnected activities.

- If trainees are to learn, it is not sufficient for the materials to merely explain the information well. Trainees must have opportunities to respond to the information, or practice the skills being taught.

- The sequence of content should include opportunities for learners to ask questions about the information or should provide exercises that require trainees to practice the skills.

- Ensure that you mix sessions to ensure that there is a balance of passive and active components.

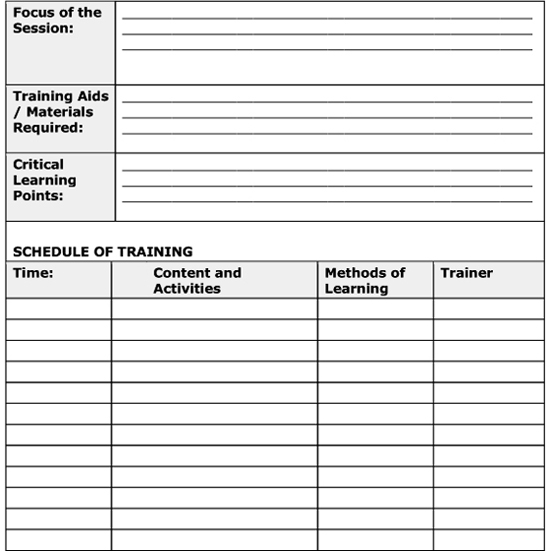

The second issue you need to consider when sequencing content is the time you should allocate to each component of content. This activity can be undertaken in the form of a daily session plan. Figure 5.9 provides an example of such a plan.

We identify four key components that you should consider.

- Focus on the Session: You should specify the primary purpose of the session, which will be determined by the learning objectives you set

- Training Aids / Materials: You should specify what materials and/or training aids you require in order to deliver the training programme

- Critical Learning Points: This is a very important component that helps you to focus on the priority content areas that you wish to include

- Schedule of Training: We will say more about this issue in the next chapter. For now, you should sequence the training content along the lines we have indicated earlier. You should also pay attention to the following issues:

- Make sure that you allow sufficient time to introduce the programme, identify the objectives and include an icebreaker, in order to create a positive learning environment

- Alternate theory/information sessions with skill/practice sessions. The former should be 20-30 minutes in duration; the latter can be longer, depending on the number of participants

- Be aware of the session immediately after lunch. This should, where possible, be a practice session or involve an activity that allows the trainees to participate in the learning process

- Allow sufficient time to review the learning and provide a summary of key learning points.

FIGURE 5.9: A DAILY SESSION PLAN

COMMON ERRORS IN TRAINING PROGRAMME DESIGN

We conclude this chapter with some pointers on the main errors that are made when designing training programmes. It is a frequent, but not advisable, situation that you may not know what your learners need to achieve. As a result, you may design a “know what” learning event when you should be designing a “know how” event. At worst, the learning event may be counter-productive. Equally, you may not make the objectives clear to the participants at the outset.

Training not Aimed at the Target Audience

Unless you have clearly analysed your training needs and considered the characteristics of your learners, the training you design may be inappropriate. It may be:

- Too easy, so that the learner’s time is wasted: they knew it all already. It may be difficult to persuade them to attend future events in the same programme

- Too difficult, so that the participants do not learn. The trainer may not explain jargon or other long words, or he/she may assume that participants know more than they do

- Irrelevant, such as giving a history of the company to an audience waiting to learn about the use they can make of a new product.

Wrong Medium of Presentation

Inexperience may lead you to rely too much on one method or make an inappropriate selection given you learning objective. For example, you may use:

- A lecture instead of an illustrated presentation. Immediately after the event, participants remember only about 20% of what they hear. This may double, if participants can both see and hear, but not if the trainer talks to, and about, his visual aids while participants are trying to read them

- A presentation instead of a demonstration and practice

- Most trainers love the sound of their voices, but participants learn skills only when they are given an opportunity to perform and practice them

- Still pictures where a cutaway model, video or film would be more effective. If the trainer wants to explain the working of a car engine, then a cutaway model is ideal.

Poor Organisation and Presentation

A whole host of problems may arise here. The main errors include:

- Material presented in an order that is illogical to the audience. If the trainer wants to demonstrate how a car is assembled, it will probably be clearer to learners if the instruction begins at final inspection and they are talked through the process backwards. They will then see how the parts contribute to the whole

- Visual aids not in the right order when needed, or even upside down. Nothing puts an audience off faster than to see a trainer searching through a pile of overhead projector transparencies for the one he/she wants next

- Visual aids illegible to all accept the front row.

- Reading a learned paper intended for publication. Trainers cannot read and address the audience simultaneously. If you have to give a paper, then present it, and use the written version to check that the argument is followed.

Insufficient Preparation

An experienced trainer may get away with a few notes. A person making a presentation, however, needs to be word perfect. A trainer whose audience can see that he is improvising loses credibility. Here are some of the more common problems:

- Poor logistics: Learners have all suffered from poor logistics at one time or another when attending learning events.

- Poor instructions on how to reach the venue: Half the group arrives late

- Room too large or too small: The audience is too scattered to form a group or so crowded that it is uncomfortable

- Room too hot or too cold for comfort

- Too much noise outside the room: The audience is distracted

- Poor acoustics: The speaker cannot be heard at the back

- Seats too hard or too soft

- Too early a start for learners to reach the venue on time

- Sessions too long: The learners’ attention wavers or they become too tired to learn

- A late finish: Learners leave early or cease to pay attention

- Coffee and tea late or cold

- Coffee and tea noisily prepared in an adjoining room, so that learners stop paying attention

- Breaks too short for people to finish their discussions and/or eat their meals

- Visual aids not available when needed

- Unsuitable accommodation for the final test

- Instructor assumes that “teacher teaching = learners learning”.

Poor Pacing

A very common fault is that trainers insist on presenting too much material for learners to absorb. Learners learn at their own pace, which can be fairly slow. Pressing on regardless will leave the audience reflecting on the last two points made, and eventually opting out altogether. Trainers may then have the choice of reaching some of their objectives fully or all of their objectives incompletely.

Bad Timing of the Learning Event

People will not appreciate an earlier start to the day than they would normally have. Likewise, if a trainer organises a training event on Friday afternoon, participants will be thinking of their weekend instead of the subject.

The Belief that Telling or Exhortation Alone Will Change Behaviour

It is very difficult to persuade employees to adopt safe practices. For example, it requires a law, or at least an enforceable rule, to make them wear hard hats or safety glasses. Managing directors who tell staff that they must all work harder if the company is to survive will have little effect, but presented with the hard facts of impending closure, the employees are likely to respond to the threat to their jobs.

BEST PRACTICE INDICATORS

Some of the best practice issues that you should consider related to the contents of this chapter are as:

- Base your learning objectives on a thorough training needs analysis process

- Involve the learner in the process of formulating learning objectives. This will ensure better buy-in to the learning intervention

- Be clear on the type of learning that is involved. Are you concerned with emphasising the learner’s knowledge, developing skills or changing attitudes?

- Be sure to specify the target behaviours that you wish to develop and use an appropriate action verb. Specify a statement of the content using a noun to describe the task and provide a statement of the conditions and the standards

- Decide on the best sequence in which to present your training content. You should be aware of the need to orient the learner, to present, to demonstrate and explain, to ensure that the learner observes and practices application of content and to get the learner to apply the content

- Be aware of the limitations of your learners when you sequence your content and when you make decisions about the amount of content

- Use your course time effectively. Decide what activities can be completed as part of pre-course work

- Each session of training should have a clear focus and a set of critical learning points associated with it

- Objectives have three key components – the learning or performance, the standard and the conditions of learning – that you should continuously keep in mind

- Your training content should reflect the learning objectives you set

- You should divide your course into clearly identifiable sessions.