Chapter 15

WHAT CHRISTIANS WANT IN SOCIETY

Someone once asked G. K. Chesterton what he thought of civilization. He replied, “It’s a wonderful idea. Why doesn’t someone start one?”

Christian social theory is a critical one because it includes ideas of what social arrangements ought to be. It has no blueprint for all the diverse sorts of societies and cultures of the earth. Yet it possesses several ethical norms that are transculturally valid. These can serve to develop a critique of the disorder in any social order.

Any critical social theory is interested in going beyond a simple description of social affairs. Evaluation and diagnosis of the rough edges of social relationships are an essential part of Christian thought. For these to be done well, there needs to be more than accurate, authentic description and valid explanation. Clear and coherent ethical norms are equally essential.

In one village, there was a man who went out of his way every day to walk by the clockmaker’s store. He would carefully adjust his watch to match the time on the clock in the store window. One day the owner of the store asked him what he was doing. Sheepishly, he said, “I’m the timekeeper at the steelworks. My watch malfunctions, and I need to know each day what time it is so the whistles starting and ending work are as close to on time as possible.”

Astonished, the clockmaker confessed, “I hate to tell you, but this window clock doesn’t work properly either. I have been adjusting it every day before I go home—by the sound of the factory whistle in the afternoon!”

How can one be precise about time when one’s only recourse is a malfunctioning watch adjusted to a faulty clock? Similarly, how can one be clear in thinking ethically about social issues? Christian faith claims that there are norms for human life that transcend the collection of standards set by faulty cultural notions of right and wrong. These norms are derivable from Scripture. They serve as a framework of directives useful for judging how good or bad given sociocultural arrangements are for humans.

These norms are not societal blueprints. The sociocultural systems that humans create are too numerous and diverse for one blueprint to fit all the contingencies and changes. Chapter Twelve argued that God’s relationship to culture is one of regulating preexisting human arrangements. From the patterns of that regulation, humans can see ways in which God’s character and commands are relevant for social critique. Yet it often takes much hard work and thought to show the connections between the norms coming from such analysis and contemporary social arrangements.1

Chapter Fourteen introduced the two major norms of idolatry and social injustice. False spirituality and oppressive sociality are destructive of the chief goods of human life. The acts of loving God and neighbor are the meaning and purpose of life. Cultural and social patterns often violate these standards. This chapter spells out in more detail some of the values and norms that orient Christian social practice and critique.

Christian Norms from the Microlevel to the Macrolevel

North American Christians normally start at the microlevel of the individual, the family, and the primary group when they think through ethical matters. This reflects the impact both of individualism and Protestantism on the culture. This is not a necessary way to begin. God most frequently addresses his covenant people jointly, rather than addressing specific individuals. The Bible certainly deals with individuals, but invariably it does so through the framework of the community of nations, the chosen people, and even humanity as a whole.

The overarching vision for human life is a social one. At the end of Scripture, the book of Revelation portrays the final events and arrangements. When the struggle against evil is finally triumphant, when human history ends with the return of Jesus Christ, God’s City descends to earth (Revelation 21–22). The New Jerusalem is a complete social world, working according to God’s design with God’s very presence at its center.

The Old Testament image for this is contained in the Hebrew word shalom.2 Shalom is the condition of people existing in perfected community within transformed nature. All relationships—with God, fellow humans, and nature—are harmonious and right. Justice and peace prevail in a righteous and responsible community. The word shalom conveys the idea of a holistic existence in which people are empowered, the environment flourishes, and God is gratefully acknowledged as Lord.

Normally translated by the word peace, shalom is not so much the opposite of war as of anything that disturbs the well-being of communal human existence. One of God’s names is Yahweh-shalom: “Yahweh is shalom.” Shalom refers to the full compass of goods that God gives to human life, including the gift of salvation for a broken and rebellious humanity. It includes all those things that bring hostility and tension in human relationships to an end. The New Testament describes shalom as present finally in the New Jerusalem.

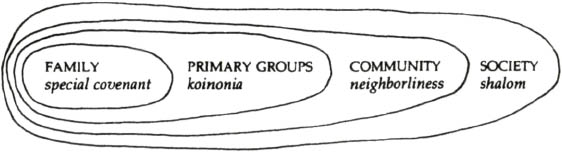

Jack and Judith Balswick take shalom to be the widest perimeter of God’s intention for human good.3 It encompasses all the other norms for social relationships and structures. Within that large perimeter, they place the Christian norms of covenant, koinonia, and neighborliness. Each norm focuses on a different level of social organization without being exclusively limited to that level.

Covenan

As the imagers of God, humans can expect the governing principles for life to reflect the God who made them. Covenant refers to the unqualified commitment of love that God graciously offers his people. He makes a covenant with Noah (Genesis 6:22), with Abraham (Genesis 15:18, 17:7–9), with David (2 Samuel 7), and so on. Jesus inaugurates the New Covenant by the sacrifice of his life on the cross. His faithful loyalty is pledged without conditions (as there would be in a contract) placed on the fulfilling of certain stipulations and terms by the other partner.

The Balswicks see covenant as involving four elements. Together these provide a guiding framework for human community, especially in the family. At its heart, covenant means a committed, firm connectedness between people, be it husband and wife, parents and children, or wider ties of kinship and friendship. The initial commitments people make in human affairs may be partial, based on fantasies and illusions; they may be only conditional. Yet the ideal is that individuals come to the place where they are committed to those in their inner circles in the way that Jesus is committed to them—without reservation, without selfishness, without limits. This is the heart of relationship: loving and being loved.

Grace (unmerited favor) is the atmosphere for that committed relatedness. It means that people live with each other on the basis of forgiveness, not law. Law demands perfection if people are to retain the rights of relationship. Legalism chokes the spontaneity and freedom necessary for healthy relationships. Grace means people work out roles and relationships so that the order and regularity that give shape to shared humanity serve the needs of all. Humans process the shortcomings and events that damage or threaten the relationship by means of the severe mercy of authentic forgiveness.4 Grace frees people for responsible, committed relationship.

Empowering is the third element in covenant. It refers to the actions and effects of interaction that create mature social relationships. Empowering “is the process of helping another recognize strengths and potentials within, as well as encouraging and guiding the development of those qualities.”5 This does not mean controlling or enforcing a certain way of doing things. It is a reciprocal, mutual recognition and enhancement of each other in a relationship. People are thereby enabled to serve and give themselves out of the strengths that God develops in them. This is not codependence but a healthy interdependence. It involves being loyal and supportive even when differences and adversity threaten to undermine the commitments that individuals have to each other.

Intimacy is the norm for communication in human social relationships and the final element in covenant. Humans possess a unique ability to know and be known, granted as part of their amazing linguistic capabilities. In the garden, Adam and Eve were fully transparent and open to each other and God. They were naked and unashamed (Genesis 2:25). In the fallen world, one experiences the effects of sin in one’s masking of true feelings and the difficulty in knowing each other. People are fearful because their social relationships are not structured by the commitment and grace of covenant. So they hide from each other and from themselves. Love, forgiveness, and empowering foster the conditions for deep levels of communication and intimacy.

Jesus made these sorts of actions and commitments toward his disciples. He loved them to the very extent of giving his life for them. He accepted and forgave them when they deserted him in his hour of need. Grace infused his every touch and look at sinful human beings. His forgiveness and love were not manipulative. He set people free and empowered them to live without fear or shame. Regardless of their social origins or the stigma that society attached to them (as Palestinian society did to prostitutes, tax collectors, and lepers), Jesus’ actions gave them new beginnings. He opened himself to them on the deepest levels, telling them all that the Father told him. This intimacy and communication were like none they had ever experienced before. Was it any wonder that his life changed all of human history?

The Balswicks see this covenant ideal as focused first on the family. Ideally, it is there that humans learn commitment, grace, empowerment, and intimacy. It is there that these actions can be practiced in their deepest forms. Christian social thought will measure family structures and role relationships in part by these Christian normative principles. Within the Christian Church, the norms of ideal role relatedness within the family extend also to those who are one’s spiritual brothers and sisters.

Koinonia

Koinonia is a Greek word referring to the relationships of a group of people united by sharing a common identity and purpose. It points at the level of social organization that is larger than the exclusive, kinship-based family and smaller than the inclusive, territorially based nation-state. Such organizations include church congregations, labor unions, professional associations, clubs, recreational organizations, and fraternities or sororities.

The closest knit group at this level is the primary group. It is the small circle of people with whom one has face-to-face relationships involving personal disclosure and emotional identification. These sorts of groups shade off into the social network of weak connections often called a secondary group. Here members share a more specific common purpose and identity and may have face-to-face dealings without strong emotional bonds. Larger organizations are secondary groups, honeycombed with primary groups. Research indicates that most people are able to sustain strong primary ties with a maximum of twenty-five to thirty other individuals.

The New Testament portrays the koinonia ideal in terms of the church. Jesus says that people are to transcend the exclusivity of their family ties by considering all who belong to God as similar to their own kin. He says:

“Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” And pointing to his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Matthew 12:48–50)

Both Peter and Paul indicate that the Church is the “household of God” within which humans are sons and daughters of God and hence spiritually kin with each other. Significantly, the chief social format for the early church was the house church. This was a small congregation of fifteen to forty people meeting in the home of a well-to-do member. This format maintained the group size most effective for creating strong ties among people.6

Koinonia was also at work in the larger Jerusalem church. It included many members from the Jewish diaspora, Galilean-derived disciples, and Jerusalem-based converts. This diverse membership developed a financial crisis. For many to stay in Jerusalem and be taught the witness about Jesus by the apostles meant they needed food and housing. Yet they were in a location where they were not employed or propertied. In response, local Palestinian Christians with property began selling their possessions and providing materially for those of their spiritual family without means. This became a fulfillment of the economic ideals articulated by Jesus.7 It also served as a prototype (not a blueprint) for the sort of koinonia (sharing, fellowship) that Christians were to extend to each other elsewhere.

In the Christian vision, one’s most intense and demanding obligations are to one’s families of origin and orientation (1 Timothy 5:3). Yet Christians are also obligated beyond normal cultural expectations of how people are to care for others in their primary groups. The New Testament makes it clear that Christians have special obligations to those who with them are a part of the household of God (Galatians 6:10). Christians are also obligated to those, Christian or not, with whom they come to have strong connections.

Many of the problems of modernity stem from the weakening of primary group ties. Social evils like racial discrimination, substance abuse, addictive behavior, the neglect of the elderly, alienation, and delinquency flourish in mass societies where such ties are exceedingly weak. Part of the task of Christian community is to foster primary groups where caring flourishes. Here people can discover unconditional love and a sharing of the life journey that will help them cope with many of the deficiencies of modernity.

Neighborliness

The outer limits of secondary groups include people who are recognized as members of one’s civic community (village, town, city, country) but with whom one has few dealings. One may relate to them casually, perhaps around an economic transaction. Yet being fair and efficient in such transactions does not exhaust the responsibility that one’s connection to these people carries. One also acknowledges their common humanness when one comes to their aid in times of crisis or special need. This ideal is set out in Jesus’ famous parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37).

If Christians’ clearest obligations are to those with whom they stand connected by the strong ties of kinship (real or spiritual) and of common primary group membership, they cannot escape the obligation that comes from their general connectedness to all other humans. People are more willing to sacrifice resources, alternative commitments, and energy for their own family than for a stranger. Parents may well bankrupt themselves to save their child. They will not bankrupt themselves and their immediate family to help an anonymous child, though they may well give substantial, even sacrificial gifts to help. The degree of help may not be the same, but the principle of connectedness is.

Jesus says that people are obligated to the stranger (and hence also to future generations). Within their powers to help, Christians are to do to others as they would have others do to them. They cannot turn away from the starving or those pressed down by injustice. They are to love their neighbor as themselves (Matthew 19:19).8 Jesus ties the sense of the proportion of help to a sympathetic principle. Christians are not to give each person what he or she deserves but what they creatively can imagine that they would need were they in the other person’s shoes.

Further, Jesus ties that creative self-sacrifice to the concrete person who may (inconveniently) show up with a real need. The neighbor (Jesus’ word is singular) is that person presented to the Christian here and now. Yet neighbor love for this individual may well involve Christians in group actions seeking better laws or institutions in the service of all individuals. While Jesus’ command focuses on an individual, it is not individualistic. It seeks the common well-being of the whole world. Yet it does not do so abstractly. The neighbor ethic requires Christians to make every human being special. Christians cannot sacrifice this or that so-called expendable individual in the service of the masses, the proletariat, or progress. Jesus’ transcendence of nationalism, gender, race, and ethnicity in this command makes it one of the most powerful engines of social justice in human history.

Balswick and Morland diagram these social ideals in this fashion:9

LEVELS OF SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND BIBLICALLY PRESCRIBED IDEALS

These are useful and helpful summary guidelines for the evaluative norms followed in Christian social evaluation. In practice, they need to be much more detailed in order to be applicable and fruitful for analysis and for strategies for change. Nonetheless, this description suggests starting points for thinking Christianly about various concrete social orders.

What is missing in this discussion so far is the larger nation-state and the global perspective. There is a very long tradition of political philosophy and legal discourse within Christian thought. Political theology is one of the fastest-growing areas of contemporary theological writings. Issues of liberation theology, Marxist-Christian dialogue, Third World theological reflection, massive global poverty, and the militarization and arming of the world’s nations lie at the center of this development.

The remainder of this chapter focuses on the Kingdom of God as the central New Testament notion with clear political overtones and implications. For two millennia, the Kingdom of God has served as the central hope and image for the comprehensive conformity of collective existence to the will of God.

The Kingdom of God and Social Hopes

Matthew summarizes Jesus’ preaching simply: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (4:17). Mark sketches the central message in similar words: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news” (1:15). Luke (and the book of Acts) repeatedly speaks of the Kingdom of God as the central theme of Jesus (Luke 4:43; 9:2; 11; 12:32; 22:29; Acts 8:12; 28:23).

This notion of Kingdom was familiar to first-century Jews. The Old Testament portrayed God as Israel’s King.10 The Hebrew word for kingdom (malkuth) refers to the abstract dynamic or idea of reign, rule, or dominion (Psalms 145:11, 13; 103:19). In Isaiah 52:7, the “good news” is defined as the announcement, “Your God reigns” (NIV, NRSV) or “Your God is King” (NEB).

The New Testament also sees the Kingdom (Greek, basileia) of God as God’s reigning activity (Luke 19:12; 23:42; John 18:36; Revelation 17:12).11 The Kingdom of God is God acting as king in the world. It means the active exercising of rule whereby God sustains creation and brings about God’s goals and victory in human hearts and history.

This notion is what unites the Old and New Testaments. The single thread joining them is the anticipation of the coming Kingdom in the Old Testament and the announcement of its arrival in the New. There are a variety of difficult issues that surround a proper understanding of God’s Kingdom in its various aspects and ramifications. We agree with F. Dale Bruner’s analysis and summary of that Kingdom in terms of the four aspects that define its chief implications.12

1. The Kingdom of heaven or Kingdom of God is the entirely future new world. When Christians pray, “Thy kingdom come,” they pray for the new heavens and new earth. They pray for the end of history, the final vanquishing of evil, the second coming of Jesus Christ. This Kingdom represents the kingly activity of God most fully known in heaven come to be present in the same way on earth. When this Kingdom comes, it unleashes unearthly forces. It is beyond human reach or acquisition. Christians pray for it to come because it is something people cannot build or realize on the basis of their human efforts. In the fullest meaning, the Kingdom of God comes with the end of the current age.

2. The Kingdom of God advances with the increase of the unadulterated Word of the Kingdom. The Protestant Reformation stressed this element. The chief means by which God’s Kingdom extends itself in this world is through the spoken Word of the gospel. The Word reaches people’s hearts and elicits faith. The Word of God’s kingship tells humans how to live and thus change history. That Word gives people hope in the final revelation of God’s Kingdom when heaven comes to earth. The future coming Kingdom is present now in truth and power when the Spirit makes the good news effective in more and more hearts and arenas of life.

3. The Kingdom of God is God’s rule in the hearts of men and women. Wherever Jesus rules in human hearts, the kingly activity of God is present. This is the sense of the Kingdom that pious and revivalist Christians have found most congenial. It focuses not on the change of worlds (from this age to the eternal age) or on changes in this world (social reform or revolution). Rather, the relevant changes are those that take place in the inner person of the individual believer. In announcing the Kingdom, Jesus called for people to turn their inner thinking and life activity around (to repent). When they do, they enter the Kingdom by submitting to God’s rule within their hearts.

4. The Kingdom of God is God’s presence in history. Wherever God’s presence is effective and active, peace and justice reign in human society. If the King is present in one’s heart, God will activate one’s hands and feet. The believer will not be passive. Rather, he or she will join with others to help God’s will be done on earth (not just in his or her heart) as it is in heaven. The social gospel movement and liberation theology underline this side of the Kingdom of God.

So the Kingdom is not simply a gift that comes at the end of history. Nor is it just the effective Word of God’s kingship, received by repentance and faith (as Christians do in their hearts). It is something to be lived out as Christians band together to bring increased peace and justice to the peoples of the earth. Human beings may not be able to build God’s Kingdom, but they can bring their own kingdoms more in line with God’s Kingdom. Today’s social worlds can reflect in a limited way the social perfections of God’s Kingdom.

In summary, “(1) the Kingdom in the full sense comes with the end of the age; (2) the major present agent of this kingdom is God’s Word, which awakens (3) the obedient response to it; then this obedient response—faith issuing in love—(4) works in and through groups and structures for justice in the world.”13 Because Christians already participate in the Kingdom of God, they are able as believers to modify their behavior and involvement in the kingdoms of this world. Christians can evaluate those human kingdoms against the elements of God’s kingly activity and rule that are described in Scripture.

Chapter Fourteen dealt with the two major structuring principles of God’s Kingdom. In God’s Kingdom, there is nothing superior to God. God’s name is hallowed and God’s will is obeyed. His loving care and covenant commitment render all evil null and void. No authority, power, or imperative structure can resist God’s reign. The great illusion that anything is more loving, more powerful, more beneficial, or more important than God vanishes. To see the true and living God is to be done with all false spirituality and foolish idolatry.

Furthermore, in God’s Kingdom humans are the object of God’s perfect, loving, and preserving activity. God is the supreme Good Samaritan, who seeks all those wounded by the evil that entered this world with sin. God is the great Shepherd who seeks lost sheep. The Lord is the suffering Servant who takes on the sin and guilt of all in order to end them. None can draw on God’s power to mistreat fellow humans. The Holy Spirit does not allow indifference or vengeance to control human behavior. God is the one who loves the neighbor as God’s self. The heavenly Father gives his unique Son to save humankind from its inevitable destruction.

There are Christians who take all of this to mean that they are commissioned to establish or bring in the Kingdom by their own efforts (although inspired by the Spirit, to be sure). This attitude has had both an evangelical and a liberal phase. Many evangelical Protestants in the first half of the nineteenth century were postmillennialists. They believed that gradual social reforms brought on by the leavening effect of Christian conversion would perfect society. When social changes reached a certain level of justice and peace, a thousand years of continuous social and international harmony and prosperity would begin. At the end of this thousand years (postmillennial), Christ would come, setting up his Kingdom. The major means to achieve this aim were the conversion of sinners and the joining together of likeminded Christians in movements to abolish such evils as slavery, prostitution, and alcohol.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the major North American Christian groups who still advocated a sort of postmillennial view were Protestant liberals and those in the Social Gospel movement. The liberal version identified the Kingdom of God with the abstract principles of love, peace, and justice. These they saw as coming inevitably through the workings of evolution, education, and Western civilization.

The Social Gospel movement was far more realistic and activist than that of the liberals. Those who embraced it did not simply wait for the Kingdom to evolve into being as the social Darwinists thought it might. They saw the massive, growing ills of the city. To solve them meant actively tackling them from many sides, using legal reforms, economic transformations, and the creation of new social structures and educational institutions. Concerted social action was essential to create new structures of justice, which the conversion of human hearts alone could not accomplish. The movement spoke of converting social structures as a parallel to converting individuals. Followers sought to do God’s will on both the individual and social levels.

What all three of these groups share is the idea that humans can bring in the Kingdom by a series of appropriate collective activities. Unfortunately, this represents a one-sided understanding of the Kingdom. The common mistake is the idea that human activity can bring in or establish God’s Kingdom. The Lord’s prayer indicates that God is the one who brings and builds God’s Kingdom. Christians can only wait for it, pray for its coming, seek it, and turn their lives about and enter it when it is near.

What these groups got right was the notion that God’s coming Kingdom has profound implications for the sorts of social arrangements to be tolerated by citizens of the Kingdom. It also profoundly influences the kingdoms that human beings build. If God’s Kingdom is one of justice, of shalom-peace, and of righteousness, what should human kingdoms be like? How do the kingdoms of this world relate to the Kingdom of God? Our answer is given in the next chapter.

NOTES

1. Christopher J. H. Wright, An Eye for an Eye: The Place of Old Testament Ethics Today (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1983); Alan Verhey, The Great Reversal: Ethics and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1984); and Stephen Charles Mott, Biblical Ethics and Social Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982) present the issues covered here.

2. See “Peace” in Colin Brown, ed., The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Vol. 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1976) pp. 777–780.

3. Balswick and Balswick, The Family: A Christian Perspective on the Contemporary Home (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1989); Jack Balswick and J. Kenneth Morland, Social Problems: A Christian Understanding and Response (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1990), p. 49.

4. Lewis Smedes, Forgive and Forget: Healing the Hurts We Don’t Deserve (New York: Harper & Row, 1984); Walter Wangerin, Jr., As For Me and My House: Crafting Your Marriage to Last (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1987); David Augsburger, Caring Enough to Forgive/Caring Enough Not to Forgive (Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 1981).

5. Balswick and Morland, Social Problems, p. 53.

6. Robert Banks, Paul’s Idea of Community (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1980).

7. Halvor Moxnes, The Economy of the Kingdom: Social Conflict and Economic Relations in Luke’s Gospel (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1988).

8. F. Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Vol. 2: The Churchbook: Matthew 13–28 (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1990), pp. 704–706.

9. Balswick and Morland, Social Problems, p. 55.

10. John Bright, The Kingdom of God: The Biblical Concept and Its Meaning for the Church (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1953).

11. George Ladd, Jesus and the Kingdom (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964) and A Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974); Leonhard Goppelt, Theology of the New Testament, Vol. I (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981), especially Chap. 2.

12. Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Vol. 1: The Christbook: A Historical-Theological Commentary: Matthew 1–12 (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1987), pp. 119–125, 243–247.

13. Bruner, Matthew, Vol. 1, p. 125.