Chapter 16

THE KINGDOMS OF THIS WORLD AND THE KINGDOM OF GOD

Few issues create more heat among Christians than how to be involved in the surrounding non-Christian world. Christian blood, shed by fellow Christians, shamefully inscribes parts of Church history because of this disagreement.

Chapter Thirteen outlined the broad spectrum of social teachings of Christian churches. Some theological paradigms seek a complete Christian civilization. The medieval European Catholic church is an example. Some seek only a tightly disciplined, minority movement of highly committed Christians. The Old Order Amish and the communitarian Hutterite Brethren are such movements. In addition, Chapter Thirteen looked at two theological paradigms of the relationship of Christianity to society: the Lutheran and the Anabaptist.

This chapter goes a step further. It outlines the position of the Reformed tradition (sometimes called the Calvinists) found among Presbyterians, Reformed churches, and other Christian denominations. These groups also seek to obey and follow Christ in the largest halls of societal life. But their theological paradigm is different from that of either the Anabaptist or the Lutheran. For them, the Christian movement can never appropriately exist simply as a small cell within the larger society, sealed off in its own attempt to be pure. If the Christian’s influence is only inward and spiritual, it falls short in part of its obedience to Christ. Nor can the Christian community appropriately concede as much autonomy to a whole arena of life in the way that the Lutherans do with their two-kingdom doctrine.

For Reformed Christians, the basic doctrine is the Lordship of Christ, his right of rulership over all the affairs of the world he made. Whatever concerns Christ concerns the Christian community. There is a legitimate distinction between church and state. But there is no legitimate boundary separating a sacred realm solely of concern to the Church and a secular realm solely of concern to the state. In some ways, the Calvinists have been the most “secular” of all the saints. They constantly seek to transform the so-called secular realm in the light of the will and Word of God. This has made them more active and politically involved than most other Protestant movements. The originator of many of their ideas is John Calvin (1509–1564).1

The Kingdoms of This World Shall Be Christ’s

W. Fred Graham calls Calvin the “constructive revolutionary.” By this he means to suggest that Calvin laid foundations for many of the ideas leading to the modernization of Western civilization. His pastoral and political involvements in the life of Geneva, Switzerland, hammered out a new pattern for Christian involvement in social affairs. His theology and social ethic created styles of Christian living that Puritans and other reform movements adopted. Austere as some of these Christians might seem, they created an activist Christianity, trying to apply the principles of God’s Kingdom to the affairs of this world. In fact, sociologists have seen fingerprints of the Calvinists all over modern economic, scientific, and political developments.

Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism develops a detailed argument that much of the ethos and spirit of capitalism comes from Calvin’s later followers. Robert Merton’s Science, Technology, and Society in Seventeenth-Century England claims that Puritans were formative in the early development of modern science. Their intense scientific activity grew out of their sense of Christian vocation and their views of God’s Kingdom. Others trace modern democratic forms of political life to the influence and ideas of Puritans and other activist Calvinism. Intense study and debate continue over the complex details of these hypotheses. Certainly these are not settled issues, nor was all of Calvin’s influence simply positive. Nonetheless, it is impressive to see how much evidence there is for intimate connections between Calvinism and modern economic, scientific, and political arrangements.

Calvin himself would not be happy with all the developments that claim to come from him. His own ideas are not fully modern. Yet they are a beginning point that changed much of Christendom. They continue to provide resources for a dynamic view of the Kingdom of God and of human kingdoms. Furthermore, Calvin’s own social identification with the poor and critique of the excesses of the wealthy have been forgotten by many of his modern-day followers. Successful “Calvinists” with money and power sometimes argue for social and economic positions completely opposite to those of Calvin—and they do so allegedly in his name. Calvin comes off sounding like a conservative defender of the status quo. He was far from that.2

Calvin’s central ideas about society run something like this. God created humans as good, bound together in original connections of love and equality. Those links shattered at the fall. In Christ, God begins the full restoration of right relationships among humans. The Church of Christ is the visible society of those whose relational connections unite them to one another in Christ. The Church’s own life is to be marked by this restoration. It is to have a corporate life exhibiting wholeness, justice, and love. Within and without its walls, the Church exhorts and disciplines Christians so that they will think and live Christianly in gratitude toward a loving God. This, at its best, is at the heart of the Calvinist vision. But the Church is also concerned with the social relationships of even non-Christians.

God’s concern is with the whole human race. Even after the fall, humans are united by a sacred bond of fellowship. The Christian’s neighbor is any and every person who shares this planet with him or her. Christians cannot be concerned simply to perfect Christian fellowship and neglect the fellowship that is God’s will elsewhere. Yet the human solidarity God desires is not readily apparent in contemporary social orders. Rather than affirming solidarity with each other, humans spoil the order intended by God. God provides a rich bounty to bless and sustain humans, but they snatch God’s rich provision, hoarding, monopolizing, and gouging others in order to enrich themselves. Some people take more than their fair share. Then they withhold the abundance they have acquired from those with nothing. This perverts the original order of nature by breaking the ties of connectedness that God designed humans to display.

The Church is the place where the restoration to good order begins. Calvin concludes that a restored human solidarity in Christ, however, does not eliminate all the inequalities of society. For one thing, the restoration God seeks is never complete in this age. The full restoration comes only with the Kingdom of God. So the Church cannot try to suppress the hierarchy that is necessary in the continuing civic and political order. Its functioning requires the order of leadership, command, and obedience. The normal order between male and female is equality. This was the original order in the garden of Eden. Yet now humans live in a provisional order. So human relationships often continue in structures of inequality in the provisional order.

When Christians teach equality, they do not eliminate differences that exist between parents and children, professors and students, husbands and wives, or surgeons and patients. Nonetheless, living in Christ provides the basis for exercising authority without oppression and for acceptance of that authority without servility or shame. Community in the Church is intended to model a new human solidarity and care. The civil order is also to experience some of God’s restoring grace. Magistrates (judges, city councillors, mayors, presidents) and citizens are to experience a similar solidarity within the continuing hierarchy. What the Church advocates is mercy and mutual consideration in all the provisional relationships that continue to be marked by hierarchy.

Wealth and power differences often mark different strata within a given social order. Some of these are illegitimate because they express sinful exploitation. Even legitimate stratification in society is provisional. Such strata as exist are limited groupings that will be set aside by the new perfected human community inaugurated when Christ returns. Already in this age the Church is to respond to that coming new human community. The Church is to arrange its own life to match its new life in Christ. Its relationship to the larger civic community will also express an awareness of that new human community. It will seek not only to transform the inner communal relationships of Christians within the Church proper but to transform the social relations of the civic community as well.

The Church is commissioned by Christ with a freedom and authority to speak God’s Word to sinful society. The larger civic society is subject to the lordship and rule of Christ. It may not know or acknowledge this to be the case. But that does not change the reality of Christ’s kingly rulership over all human affairs. His Word is not a limited message, meant simply for true believers. It is a Word that speaks to the whole of human life and aims at claiming it back for God’s Kingdom.

The persistent tendency of sinful society is to set up illegitimate social strata and to exploit legitimate strata. Society regularly is run in accord with the self-interest of those who benefit from its social and economic arrangements. Where this is happening, the Church must speak in no uncertain terms. Where human solidarity and compassion do not govern social relationships, there the Church will speak and act prophetically within society. How it performs this speaking and acting in society is what sets apart the Christ-transforming-culture position from the Lutheran and Anabaptist approaches.

There is an undeniable separation of church and state according to Calvin. Yet both exist under the single Lordship of Jesus Christ. So the Church cannot avoid being active in its relationship toward the state. On the other hand, the state cannot dictate to the Church. To allow civil rulers to rule the Church as well is a confusion that damages the mission and identity of the Church. The temporal cannot subordinate the spiritual. Yet the spiritual must seek to transform the temporal in the light of the eternal order of God’s Kingdom.

For Calvin, the Church has four principal tasks in service to the state. It prays for political authorities, encourages them to defend the poor and weak against the rich and powerful, calls on their help in promoting true religion (even to enforce ecclesiastical discipline), and warns the authorities when they are at fault. Many non-Calvinist Christians would probably happily agree with the first two duties and with the last. Yet all sense a problem with the third task of asking political authorities to promote true religion. It is here, in fact, that Calvin displayed some of his most dramatic failures of Christian love and compassion. Nonconformists in Geneva were silenced, expelled, and, in a few cases, executed. To be fair to Calvin, his own efforts at insisting on mercy and compassion in civil affairs were often frustrated by political authorities.

By insisting that the Church could warn political authorities when they were at fault, Calvin laid the foundation for modern notions of free speech. He also went a step further than Luther as to what can appropriately be done when the political authorities stray far from civic righteousness. Luther was content to allow resistance to evil and obedient suffering. Calvin permitted revolt and rebellion at times. Calvin cared deeply for the poor and the refugee. He pressured the government and sought laws to protect the weak and curb the flagrant conspicuous consumption of the rich. Yet he did not advocate revolutions of the hungry and the poor on their own behalf.

If these people are to revolt, according to Calvin, they must first find allies among the lower government officials. Rebellion or revolution is legitimate only when led by the lower magistrates against higher corrupt ones. These legitimate political officials in the lower ranks must agree with the poor and oppressed that the government has subverted its God-given duties. Then, if the corruption will not be cut out, revolt may be the only recourse. Even violence can thus be a legitimate Christian act when it restores a corrupted state to its true functions.

For his day, Calvin advanced dramatically new ideas about wealth and poverty, as well as about commerce as a means to wealth. For Calvin, wealth is not a necessary sign of God’s favor and election to heaven. Weber’s portrait of the latter-day Calvinist and capitalist, viewing worldly commercial success as a sign of God’s favor, represents a departure from Calvin’s ideas. Such “Calvinists” forget and distort what Calvin himself said about wealth and poverty and their place in God’s restored human community.

If wealth does not signal God’s election, neither does poverty serve as a proof of God’s displeasure and election to hell. Both in fact are spiritual opportunities and dangers. Both wealth and poverty are channels of grace from God. They are means by which people can demonstrate the human solidarity that comes from authentic faith. Yet the wealthy, for the most part, reject the grace that God bestows with their wealth. Instead, they idolize their possessions, making it virtually impossible for them to enter the Kingdom of God. God calls them to use their wealth for the benefit of the commnunity, especially the poor.

The rich abundance that comes from God is to be used according to a rule of love, not a rule of asceticism. Asceticism is no more a proper response to wealth than is luxurious self-indulgence. If people keep too little and deny themselves too severely, they put themselves in bondage to their own untended appetites and eventual ill health. They must keep enough of what God gives them to live simply. But the poor are God’s messengers in society, placed here to check on the faith and charity of those with means who claim to walk with God. The well-to-do are to give out of their plenty to these messengers of God. If instead they indulge in extravagances and conspicuous consumption, they put themselves in bondage to the passions of the sinful self and to mammon. The poor help free the rich from the idolatry of money by giving them the opportunity to break with its power.

The simple act of giving, however, is not enough. The charity that serves to boost the prestige and name of the giver is well known. So is the charity that reflects no more than giving a pittance off the top of a fortune. Giving is to be done on the basis of compassion (the rule of love), even when it might cut seriously into one’s own comfort. Such giving must not demean the poor, for one is giving to one’s brothers and sisters. Giving is not only to show but to foster a restored human solidarity in love and equality.

Overall, Calvin’s economic ethic means that anything contributing to the impoverishment of a part of society is evil. He had particularly harsh words for those engaged in monopoly and speculation, making money off the misery of others. His ethic, however, does not undermine private property. Private property really is private. But what makes it legitimate are the uses to which it is put. Private property must be used for the common good of society. The modern notion that one has a right to do whatever one wishes with private property is foreign to Calvin’s vision. He affirms the individual and individual rights without falling into the trap of extreme individualism.

Calvin was a pragmatist in all these matters. What he sought was the rule of love in human affairs. Laws and political restrictions are a legitimate and necessary means to curb the abuses of human selfishness. Humans will never live in a perfected society with completely unselfish people before the coming Kingdom of God. But human affairs can be arranged to curb selfishness, encourage human solidarity, and develop compassionate relations in the remaining hierarchies of wealth and power. Government interference is legitimate insofar as it promotes the general good and happiness of people in society. So the state serves to guard against business interests milking the populace. Yet the state itself cannot become an economic liability to its citizens either. Neither business nor government has unlimited rights to secure for itself the wealth created in society. Nor does the private individual have unlimited rights in property to hoard goods or to live a wastrel life of conspicuous consumption while other people starve.

In contrast with most thinkers of his day (including Luther), Calvin approved commerce as natural to the ways in which humans relate to each other. Exchanging goods is how God’s provisions for human needs get distributed throughout society. For Calvin, no human activities are free from the corruption of evil (including farming, theologizing, pastoring, and politicking). Commerce is not in a different moral universe from “spiritual activities.” Commerce is as good a form of work as any other human activity. And work is a necessary part of people’s God-given task in society.

In spite of the curse pronounced by God on human labor, people are given the gift of work by God. To be sure, work is a fallen good. Yet each person must make a choice of occupation. Any occupation is relatively good, provided it is not banned or condemned by the Word of God. The goodness of any occupation or work is measured by the degree to which it serves the common good. Work is to benefit the whole Church and the larger global human community. When people do not work, they disobey God. Work does not mean a salaried job but activity that creates goods or performs services vital for other people’s well-being. Whatever denies work to human beings corrupts the very structure of their existence and must be resisted. Work must, thus, be undertaken in conditions that are safe and not oppressive. God’s will does not allow abusing the work of others.

So far as wages are concerned, no one deserves what he or she gets, whether as employer or employee. What one gets comes through the goodness and grace of God. Nonetheless, those who hire others for their labor are responsible for paying a just wage. A just wage is not based on the legal minimum that one can get away with when compensating a worker. It must be based on the norm of equity, rooted in the command, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” The employer must put himself or herself in the place of the worker and seriously consider what he or she would want to receive in order to be supported in a life of dignity. Because the ultimate wages come from God, what the employer actually is doing is paying out God’s wages to God’s servants. Not to pay proper wages is to defraud and embezzle from God.

Self-interest in matters of wealth is so powerful that something more than good religious ideas about working conditions and wages is needed. Employers (and employees) are often blinded by their own selfishness. Thus, binding contracts expressing agreements are necessary. So are laws dealing with general wage structures. Both of these measures are useful for defending against common inequities and injustices. The rule of love is the basic norm for Christians in civil life as in churchly affairs. Laws regulate human arrangements and ensure a measure of genuine justice in the context of human selfishness. However, Christians cannot take what is legal as the measure or standard of their own conduct. What is legal may be prohibited to the Christian because it falls short of the law of love.

One implication of these ideas is that pastors and Christian leaders should seek to speak to and influence every realm of human life. There is no part of the world that does not belong to God and is not subject to his Lordship, even in its rebellion. While Calvin and his followers accept the distinction between church and state, they refuse the false line between the sacred and the secular. Calvin’s vision was ahead of his own time, however much some of his ideas are now behind the present times. Fred Graham is correct when he says:3

[Calvin’s] ability to distinguish the spiritual and the temporal was uncommon for his day; his refusal to allow the spiritual to be subject to the temporal was uncommon to Protestantism in his day; his ability to suffuse the temporal with the values of the spiritual without robbing the former of its identity is instructive for our day.

Calvin was thoroughgoing in his concern for all affairs of human life, including government. He understood the gospel as something irrevocably concerned with the world in all its affairs. The Church is involved with and concerned for the full range of affairs over which the Lordship of Christ extends. Calvinism through the centuries shows a persistent tendency to involve its followers in the political order, for better or worse.

A Contemporary Expression of Calvin’s Social Doctrine

By many accounts, the greatest Protestant theologian in the twentieth century is the Swiss Reformed thinker, Karl Barth (1886–1968). Some of his ideas are controversial and clearly contestable. There are places where evangelicals disagree most sharply with him. But his resistance to the Nazis in Germany gave him a distinct view on the relationship between the Church and the contemporary state. In 1935, while a professor at the university in Bonn, Germany, he refused to take the required oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler. He was removed from his government teaching post. From Switzerland, he maintained close relations with the Christian resistance, the Confessing Church of Germany, which he helped bring into being. Over the years he wrote extensively about the Christian’s responsibility for the state and civil society.

Barth was a Reformed theologian who followed many of Calvin’s basic ideas. He agreed with Calvin that Christians cannot leave the larger social order alone. Christ claims all of one’s life, not just one’s heart. Spelling out what this means is a complicated, prayerful responsibility of the total Christian community. Furthermore, it can be done properly only when Christians place themselves in solidarity with the poor and the weak. Only then do they place themselves in solidarity with Christ, who himself was poor and weak.

The foundation for any sort of Christian ethics, according to Barth, is theological. To discern the political responsibility of the Church, Christians must have a theological understanding of the state and politics. Only then can they spell out how to act Christianly in the political arena.4

For Barth, the primary understanding of the Kingdom of God (the heavens) is as a transcendent, future reality. This being the case, no this-worldly sociopolitical reality can be identified as God’s Kingdom. The discontinuity between God and the world means that faith can identify no principle, program, party, or structure directly with God’s action. God’s action is God’s action. The actions and principles of this world are of this world. The Kingdom of God does not come through the activity of human beings. Nor is the Church to be considered that Kingdom, as advocates of Christendom or a Christian civilization often do.

Nonetheless, the distance between God and the world is overcome by Jesus Christ. It is he who stands at the center not only of the Church but of the world.5 There is no limit or boundary to the Kingdom of God. It has invaded this age and made its presence known in Jesus Christ. The fact that the Church is peculiarly commissioned to announce the objective facts of Christ’s reconciliation in the world is a sign that there is a preliminary sanctification of this world. Both the Church and the state are “orders of reconciliation,” established by God’s grace in the time that stands between the resurrection of Christ and his coming again.

Reconciliation is in fact the central sociopolitical event of world history. It objectively grounds the Church as the realm of those who have obediently heard the Word of God. And reconciliation establishes the state as the realm that provides an external, relative degree of justice, freedom, and peace within which the Word can be proclaimed. Both church and state have tasks given them by God to accomplish for the good of all human beings.

In Barth’s thought, the two realms of the Christian community and the civil community can be distinguished, even if both are rooted in the reality of the Kingdom of God. They each have a distinct commission to fulfill. The Church is the gathered community of people who come together by virtue of their common, conscious knowledge of Jesus Christ. The Church’s commission is the direct service of the Word of God, the dissemination of a message that it alone is given and knows.6 So the Church is always preeminently concerned with the study, purity, and proclamation of God’s Word to all the world.

The state is commissioned also for the service of God but not for the direct or conscious service of the Word of God. Its service is to provide a social order of outward justice, peace, and freedom. These are not the justice, peace, and freedom of the Kingdom of God. Rather, they are the promise of these things in the midst of the chaos of the kingdom of the world.7 The state accomplishes this commission only by recourse to physical force or to the threat of such force. This is what is learned, not only from direct experience, but from Romans 13. The state bears the sword and exercises power, not just authority. The essence of the state, however, is not power. Its essence is justice. But justice only occurs in a sinful world by the state resorting to power.8

The Church claims the state for this service of God by prayer, by vocal advocacy, by refusing to obey the state when it is disobedient to God, and by sending its members into the highest offices of the state. Yet in claiming the state for the service of God, it does not seek to turn the state into the Church.9 Nor is the state to seek to turn itself into the Church. The Church cannot take the Kingdom of God into the state or expect the state to become the Kingdom of God. What it seeks from the state is that the state fulfill its divine purpose and destiny. It must be committed to justice in principle (a “justice state”) and must provide a relative degree of actual justice in its day-to-day functioning (a “just state”).10 It is to be the servant of God that Paul pictures in Romans 13:1–7, limiting and punishing the evil while encouraging and rewarding the good. It is to be a parable or promise of the Kingdom of God by reflecting on a human scale and in a limited way the qualities of God’s Kingdom. In its limited, flawed, even fallen way, the state can to some degree function in ways that will remind people of what the Kingdom of God is like.

Barth claims that what Christians need to do is actively engage themselves at every level of civic and political life. They alone consciously know the divine commission and task of the state. The modern state is secular and does not openly acknowledge the Word of God as its rule and guide. So Christians must be thoughtfully present in the civic arena, pressing for and advocating policies and decisions in line with justice, peace, and freedom. Part of this presence will be as elected or appointed officials.

For Barth, this does not mean that there ought to be a Christian political party or a Christian platform. In the civic arena, Christians seek the priorities and principles of the Kingdom of God. They wish the state to mirror in limited ways what the Kingdom of God is like. But that happens only through the regular course of debate and legislation where the ideas of Christians must compete with and succeed over many other ideas. The Christian is present in the civic arena as a citizen. There the discourse is not about the Bible and the Word of God. It is about what will further the common good of all citizens.

So Christians, having discovered principles of justice, peace, and freedom from their own deep study of Scripture and society, enter the civic arena “anonymously.” They come to speak as citizens with no special privileges or even special insight other than the general knowledge of the state’s divine commission. God does not give Christians detailed blueprints for political and social action. They will not quote Scripture as authoritative in this realm, for it does not have that status in the civic arena. Nonetheless, Christians will seek valid arguments, persuasive in a secularized civic arena, for social changes that will enhance and encourage the rule of human solidarity and love.

The reality of sin in this age means that the state, no less than the Church, can be subverted and that it will not function to fulfill its divine commission. The state can become an antistate, a state of chaos rather than order (just as the Church can become an antichurch that proclaims the word of the human instead of the Word of God). Because of the objective fact of Christ’s reconciliation and triumph over the principalities and powers, however, this age will not see either the full face of the state as the Beast (Revelation 13) or the Church as the Antichrist. The powerful triumph of Christ on the cross objectively limits the ability of church and state to be subverted from their God-given tasks.

For these reasons, any particular, empirical state functions somewhere between the New Jerusalem (the Kingdom of God) and Babylon (the state as the Beast). One must always exercise discernment and wisdom in determining whether the actual government one faces has enough justice in it to legitimate its continued existence. If it is committed in principle to justice and struggles in practice to deliver justice to its citizens, Christians will seek to reform and correct it by all peaceful means. If a state in principle is no longer committed to justice (as happened in Nazi Germany) and even acts to punish the good and reward the evil in practice, then the Christian may revolt against it even by violent means. It no longer is a state but has become an antistate, a government of disorder and injustice in principle and in practice.

So the Christian and the community of Christians carry the responsibility of seeking the transformation and reformation of the larger civic community, including the state. Christians cannot be unconcerned and uninvolved in a realm where God is concerned and involved. If Christians are citizens of the Kingdom of God, they will also become motivated, compassionate, courageous change agents in the kingdoms of this world. If their hearts are transformed and obedient, their hands and feet will move to care for the hurt and impoverished in their societies.11 But how? Is there a Christian or biblical philosophy of change?

Christian Approaches to Social Change

The Anabaptists typically see the transformationist approach to society as prone to fall into the arrogance of attempting to manage history and into the folly of using sinful means (coercion) to do so. The Calvinists, they say, have a history of failure because they overestimate the degree to which the state and the larger civic community can be transformed this side of the coming Kingdom of God. The transformationists normally reply that the Anabaptist approach borders on a counsel of despair. Much more can and has been modified by Christians’ active political involvement in social change than the Anabaptists recognize. Even if the effort at transformation fails, it must be made in obedience to and solidarity with the universal Lordship of Christ. But their debate will probably not be settled in this lifetime.

Whatever one’s conviction about the appropriate biblical approach to social involvement, it is clear that all Christians need great wisdom and understanding. The Bible stresses wisdom and discernment in human affairs because these affairs are so complicated that simple formulas cannot handle them. Besides, the human beings who occupy positions within social structures are of infinite value and often fragile creatures. They need to be handled with care. This takes change agents of maturity, love, and discernment. Unfortunately, people don’t become such agents by learning a dash of management theory, a trace of sociology, a pinch of change agentry, and a bushel of political policies. It happens through one’s concrete immersion in the lives of real people who are struggling to survive in the immensely varied worlds of wealth and poverty, power and oppression, sophistication and illiteracy.

The disagreements and strategies of social change can be categorized roughly by a few key distinctions and questions. Virtually all Christians believe that they can do something about the world they live in. They can certainly intercede for its hurts and pray for its compassionate healing. They can pray for God’s forgiveness on those who do evil to them and bless those who persecute them.

But many feel that there is much more that Christians can do to live out their faith as whole people. They do not exist simply as devout Christians cordoned off in holy huddles. They are also parents, teachers, social workers, health care professionals, truck drivers, secretaries, executives, politicians, sales clerks, poets, musicians, and athletes. They are most definitely in the world. Many of the deficiencies of the Christian movement are not due to the Church not being fully Christian. Many are due to the fact that Christians are not thinking and living Christianly in the world.

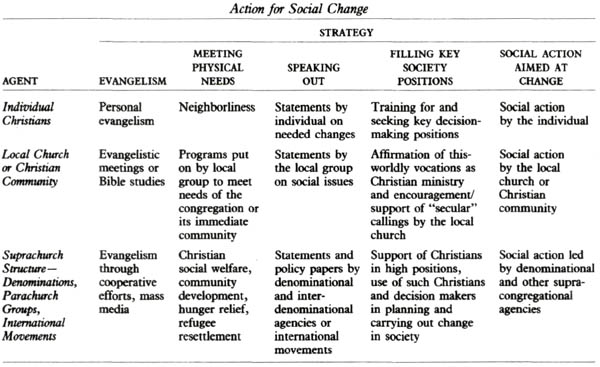

When humans confront the awesome and frightening disintegration of the social fabric of modern industrial orders, they must do so as Christians possessing a variety of options for social change and transformation. The following chart summarizes the major options in terms of two major distinctions: who is to bring Christian influence to bear (the agent of change) and what sorts of actions will be used to effect change.12

The agents of change may be individual Christians, seeking through personal action to bring about greater justice, peace, and freedom in their own small circles of life. Some Christians argue that this is the only legitimate way in which the Church should be involved in the world. It ought to equip individual Christians with motives and insight and send them forth to live as Christians in the world. But the Church has no further responsibility or duty toward the larger social order.

Others consider the local church congregation as an important agent of social action. Thus, they see ministry radiating from the congregation into the world, setting up soup kitchens and food distribution centers, sponsoring refugee families, hosting clothes closets for the poor, lobbying against social evils. Others move a step further and see the denomination or even transdenominational organizational structures as appropriate actors for social change.

Then there is the spectrum of possible actions that can be taken to produce changes in the social world. Evangelism seeks to bring the Kingdom of God to the hearts of people. It invites intimate, personal changes in a person’s life. Conversion of the heart serves as the basis for conversion of life, thought, and habit. Most Christians would also argue that the action of direct relief of those suffering is mandated by Matthew 25. Extending the cup of cold water, clothing the naked, feeding the hungry and housing the homeless, visiting the prisoner and caring for the sick—these are all appropriate actions Christians can take in this world.

More controversial are the last three sorts of action listed in the chart: speaking out and making pronouncements on social arrangements, seeking to place Christians in pivotal positions of power, and taking direct, confrontational social action. Pronouncements, especially those made by denominational or transdenominational agencies, always provoke the ire of Christians who do not agree with them. Some churches reject the idea that one can be a Christian military general, police commissioner, or even president. Others see direct (even nonviolent) protest or action as beyond the boundaries of Christ’s commission.

We are not attempting here to prescribe the correct answer so much as to display the range of options used by Christians of different stripes in the some two-hundred-odd countries where they reside. For the Reformed Christian, all of these options are legitimate tools in fulfilling the secular duty of the Church and seeking social transformation. The critical question is what each of these agents and actions can accomplish in moving the world toward higher levels of justice, peace, and freedom.

As in the case of the Anabaptist and Lutheran traditions, the sociological vocation is an important and valued one among Reformed Christians. Sociology serves to clarify the changing structures of societal life to which Reformed Christians seek to apply the law of love and justice. Sociology is a modern-day extension of the sort of social analysis that Calvin himself conducted as part of advocating a civic order that served the common good. It is another opportunity for the transformationist impulse to be put into practice. In this case, the transformationists seek a sociology integrally related to glorifying God by thinking Christianly. To think and live Christianly here is to relate Christ’s Lordship to social reality. For Christians, this is a calling worthy of our lives.

But how can Christians take what they know of Christ’s Lordship and of societal structures and bring about authentically Christian social analysis? That is the topic of the last chapter.

NOTES

1. William J. Bouwsma, John Calvin: A Sixteenth-Century Portrait (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); W. Fred Graham, The Constructive Revolutionary: John Calvin and His Socioeconomic Impact (Atlanta, GA: John Knox, 1971); Alexandre Ganoczy, The Young Calvin (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1987); John T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954).

2. The following section is heavily indebted to Graham, The Constructive Revolutionary.

3. Graham, The Constructive Revolutionary, p. 158.

4. Karl Barth’s Knowledge of God and the Service of God (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1938), pp. 219–239, and Against the Stream (New York: Philosophical Library, 1954), “The Christian Community and the Civil Community,” are excellent, succinct statements of his theology of the state and the church.

5. Barth, Knowledge of God, p. 221.

6. Barth, Against the Stream, pp. 15, 22–23.

7. Barth, Knowledge of God, p. 221.

8. John D. Godsey, ed., Karl Barth’s Table Talk (London: Oliver and Boyd, 1963), P. 75.

9. Barth, Against the Stream, p. 30.

10. John Howard Yoder, in Karl Barth and the Problem of War (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1970), pp. 50, 125, notes the important distinction in Barth between the gerechte-Staat (“just state”) and the Rechtstaat (“justice state”).

11. Nicholas Wolterstorffs Until Justice and Peace Embrace (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1983) offers a fine example of a Reformed theology blended with sociological world systems analysis to suggest priorities for Christian transformational action.

12. This chart is based on Jack Balswick and J. K. Morland, Social Problems, p. 314. What this chart adds is the action of seeking occupational positions that provide societal leverage for effecting certain sorts of social change.