Words that Matter in a Harsh Land

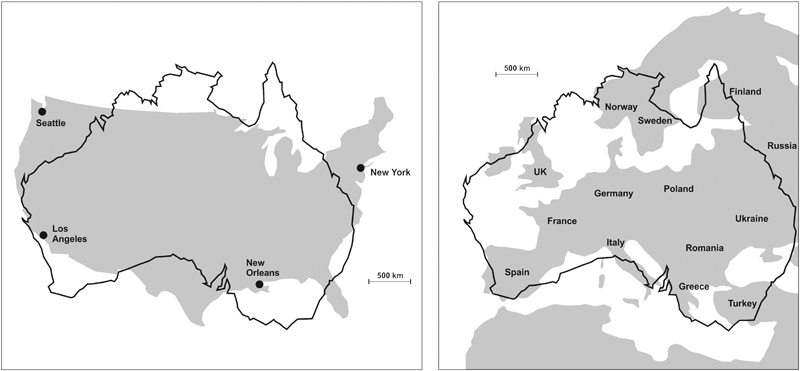

Not everyone everywhere knows as much about Australia as do Australians, although a dispassionate observer of world geography might rightly wonder why. For Australia is massive – pretty much the same size as Europe or the conterminous United States (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The size of mainland Australia compared to the sizes of the conterminous United States (left) and Europe (right).

About one-third of the continent of Australia is real desert. Most of the rest is also quite dry, making Australia, after Antarctica, the world’s driest continent. For humans bent on settling Australia, its arid heart in particular has long proved a challenge, yet the first arrivals not only traversed it repeatedly but also occupied it, establishing desert cultures that flourished for tens of thousands of years. We know little of these first people’s journeys of exploration, their successes and failures,1 but there is a far more complete record of European exploration of Australia’s forbidding interior that allows a taste of such encounters.

Consider one of the first such explorers, Charles Sturt, who – buoyed by rumours (unfounded) of an inland sea – travelled across south-east Australia in 1828–1830, reporting on the Murray and Darling river systems that dominate its drainage. Sturt barely had a good word to say about anything, it seems, finding little water (much of what he found was too salty to quench the thirst),2 and the plains ‘dreary’, barren and seemingly limitless. Sturt’s apologetic judgement of Australia’s interior was that ‘there is no life upon its surface, if I may so express myself; but the stillness of death reigns in its brushes, and over its plains’.3 Yet his belief in an inland sea lingered and he led another expedition into Australia’s dry heart in 1844–1845, reaching its geographical centre in the Simpson Desert. But there was no trace of the inland sea and, battling scurvy, he headed home.

In part, Australia owes its conspicuous dryness to its topography – it is the world’s lowest continent, with barely any land more than 1,000m (3,280ft) above sea level – which in turn is explainable by its geological history (see colour plate section). Currently the best model to explain the evolution of the Earth’s surface is one – called plate tectonics – that pictures the entire Earth’s crust as broken into a jigsaw of rigid interlocking pieces named plates, each of which is moving relative to the others. Along plate boundaries, adjoining plates may converge (often forming mountain ranges, causing volcanic and earthquake activity) or diverge (generally associated with rifting and volcanism). Sometimes two plates simply slide past one another, sticking, then periodically slipping and causing earthquakes.

Uniquely among the world’s continents, Australia lies wholly within the middle of a crustal plate, far from the main sites of geological activity where plates are created or destroyed in paroxysms of seismic and volcanic fury. And, because Australia has been so located for around 34 million years, there has been ample time for denudation to work on removing its surface irregularities, unchallenged in almost every part by the mountain-building processes that have created young topography on other continents. Yet it would be wrong to imagine that distance from plate boundaries renders the Australian continent wholly immune to geological disturbances. The continent is criss-crossed by faults along which stress from movements at distant plate boundaries may occasionally shimmy. The real wake-up call in this regard was the Newcastle Earthquake on 28 December 1989, a magnitude 5.6 event in a place long regarded as seismically inactive that prompted a new and improved awareness of earthquake risk across the continent.

While most geological activity on Earth is concentrated along plate boundaries, there are places in the middle of plates where magma reaches the Earth’s surface from within. Named hotspots, these places are commonly sites of active volcanoes and – most importantly – are usually stationary over long periods of time. This means that when a plate moves across a fixed hotspot, you get a succession of volcanoes being built: the youngest one sits over the hotspot, while the progressively older extinct ones trace the line of ancient plate movement. The best-studied example of such a hotspot chain is the Hawaiian Islands, in which two active volcanoes (Mauna Loa on Hawai’i Island and underwater Lo’ihi) lie above the hotspot; then, stretching away to the north-west for some 5,800km (3,600 miles), is a line of ancient volcanoes, each progressively older, which mark the passage of the Pacific Plate over this hotspot for an incredible 65 million years.

There are also hotspot chains in eastern Australia, formed when the plate of which the Australian continent is part moved over a series of fixed hotspots. The longest such chain is the Cosgrove Track, displaying a record of volcanic activity from nine to 33 million years ago (see Figure 6.1). But if the Cosgrove volcanoes are long dead, the same cannot be said for a cluster in the south of the continent, the youngest of which is Mt Gambier. Once thought to be of hotspot origin, recent research has proposed that this volcanic activity may instead have been caused by the reactivation of a long-dormant fault system along which magma has fortuitously been able to reach the surface. Yet such activity has barely affected the form of Australia as a whole. Today, being distant from plate boundaries and relatively unaffected by what happens there, the main cause of landscape change in Australia is erosion. This slowly lowers the ground surface and irons out its irregularities, creating massive quantities of detritus that fill those that remain, and thereby creates the vast, apparently featureless plains that dominate the interior.

Within the last 34 million years in Australia, the work of denudation – or land-surface lowering – has been assisted by the continent’s inexorable move into increasingly warmer climate zones. At the start of this period, recently separated from the continent of Antarctica (part of the ancient Gondwana continent), Australia was located in the very cold and dry high latitudes of the southern hemisphere. Since then it has steadily moved north into lower latitudes.4 While punctuated by wetter episodes, which were comparatively short-lived, the aridity that currently dominates Australia’s climate started to affect the continent about 10 million years ago, when it reached the horse latitudes: those zones of the Earth where the high-pressure atmospheric conditions result – for most of the time – in warm weather, weak winds, few clouds and above all little rainfall.

You might therefore expect that the surface of the Australian continent has been little altered from the time it first formed – but of course this is not the case. Time is the great leveller, for the Earth-forming processes of weathering and erosion, however slow they may be, are relentless. Across almost countless eons, driven by changing temperatures, wind and rain, and running water, the land surface of Australia has been worn down. A lack of processes such as volcanic eruptions and land uplift, which elsewhere in the world rejuvenate ancient land surfaces and cause lost nutrients to be replaced, has led to a situation in Australia where soils have been weathered and leached repeatedly.

Being dry, low and somewhat slothful as moving continents go does not sound like a great recommendation for the study of Australian geology, but the reality is quite different. Australia is composed mostly of continental (not oceanic) crust, and is home to some of the earliest-known rocks on Earth, formed almost 4.5 billion years ago, outcropping in the Jack Hills of Western Australia.5 In the same region, the remains of some of the very first life forms to appear on our planet are found. Known as stromatolites, they lived in colonies and built structures using carbonate extracted from seawater. There are living stromatolites in Shark Bay, yet a few hundred kilometres away they are found as fossils in rocks that formed 3.5 billion years ago, intriguingly close to the time Planet Earth came into being.6

Beneath the blanket of weathered sediment that covers most of the Australian landscape lies a complex pattern of bedrock testifying to the billions of years the continent has existed.7 Some of this bedrock represents the cores of ancient continental masses (cratons), while other bedrock consists of remains of the sediment-choked basins that accumulated around them. About two-thirds of Australia’s basement formed more than 500 million years ago.

Big land masses provide more opportunities than smaller ones for terrestrial life. Newly arrived organisms can spread out in many directions, possibly multiplying uninhibitedly at first, utilising the food sources they encounter. Food species might renew themselves indefinitely while predator population densities often remain low, below an area’s carrying capacity. Such a scenario is thought to explain why the first Australians – ancestors of today’s Aboriginal peoples – were able to successfully follow a largely nomadic way of life for more than 50,000 years; no other was needed to survive. Yet the climate of Australia also localised the possibilities for life that might otherwise be expected from its great size. Rainfall is concentrated along the continent’s fringes, leaving a vast arid interior that poses many challenges for living things – including humans. Winds that blow onto Australian shores, often laden with moisture from their cross-ocean travels, drop most of it within a few hundred kilometres of the coast, then continue blowing inland. They are dry and pick up dust as they howl across the great inland plains to the furthest inland places where, finally, the wind losing power, the dust drops to the ground, driven into dunes in the sandy deserts.8 Some of the deserts are stony – this is where renewed winds have removed the finer particles, leaving behind those it cannot readily shift.9

Compared with continents of similar size, there are not many large rivers in Australia, especially in its western half. In the centre, dry riverbeds connect series of dry lake basins that only rarely become filled with water. On such occasions, usually when a La Niña event is in progress, the desert turns green, its livelihood possibilities burgeon and its living inhabitants rejoice. When some of these lakes are brimful with water, their surfaces may become very flat and they may become almost indistinguishable from the sky when the sun is high: a phenomenon that may have given rise to legends about a vast inland sea. On his last expedition, so convinced was Charles Sturt that he would find the inland sea, he took a boat along so that he would be able to paddle across it once he found it. On 13 May 1845, an elderly Aboriginal person stayed in Sturt’s camp and was ‘greatly attracted by the Boat … the use of which he evidently understands’. Mesmerised, Sturt reported that this man ‘pointed directly to the northwest as the point in which there was water, making motions as if swimming and explaining the roll of waves, and that the water was deep’.10 Sturt’s informant is likely to have been describing the Indian Ocean, although maybe memories of times when the dry lakes periodically filled clouded his thoughts. There has never been a sea in the centre of Australia.

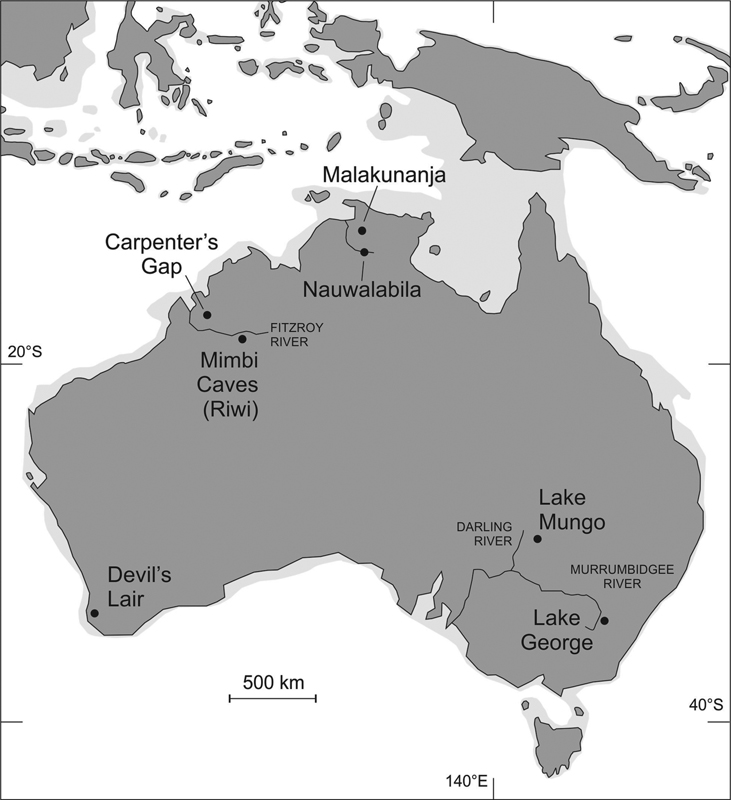

The earliest known traces of human settlement in Australia date from some 40,000–60,000 years ago and are not found along the modern coast. They are found inland, typically beneath rock overhangs or in shallow caves where people once sheltered, commonly hundreds of kilometres up river valleys from the modern coastline. So of course these places cannot be the first that people settled in Australia. They must have set foot on the land hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years earlier than the time they reached these inland shelters, but those first footprints are forever lost to us today. This is not simply because no earlier indications of a human presence in Australia have been found along its coasts, but also because at the time people arrived here first, the sea surface was much lower than it is today. The shore on which the first people landed is now under tens of metres of ocean water, probably buried by sediments washed off the land, and perhaps even grown over with reef.

So can we know where and when the first Australians actually became Australian, or when the first human footprint appeared on Australian shores? We can use various methods to get approximate answers to these questions, including the reconstruction of the easiest series of sea crossings from Asia, or genetic tracing or even historical linguistics, which tell us where in Australia the majority of extant Aboriginal languages originated. All this is discussed later, but it is sensible to begin our quest for the first Australians by looking at the places where they first manifested themselves.

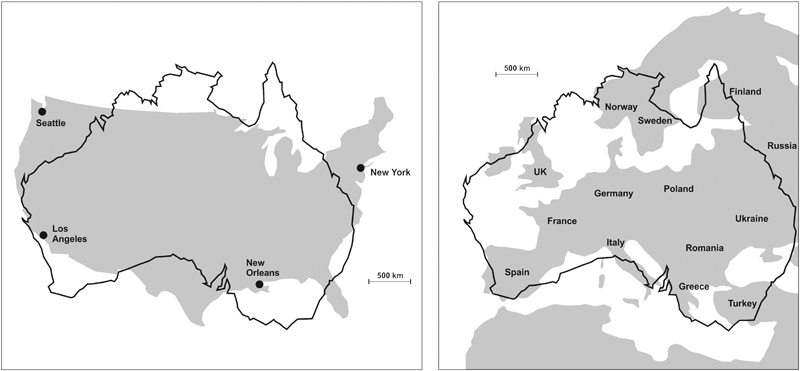

Determining ages for the earliest human settlement sites in Australia suffered for a long time from being beyond the reach of radiocarbon dating – approximately 40,000 years – but within the past 25 years newly developed techniques have been applied to diagnostic material from ancient sites that allow their ages to be accurately determined. Several such early sites are discussed below; their locations are shown in Figure 2.2.

In northernmost Australia are found a number of ancient sites, notably the two rock-shelter sites of Malakunanja,11 and Nauwalabila (in the somewhat alarmingly named Deaf Adder Gorge). Dates for the deposition of sand containing the oldest human-made stone tools (artefacts) at Nauwalabila range from 53,000 to 60,000 years ago,12 while those at Malakunanja are sandwiched between sediment layers dated to 45,000 and 61,000 years ago respectively.13

The earliest Australians used tools they made from stone, and perhaps shell, which they would have discarded when they ceased to be functional (or cherished) – like we often throw away things we no longer need or want today. Stone tools often endure the ravages of millennia, and should we find them today, we can often work out how long ago they were used – and thus approximate the time when their users occupied a particular place. So much of the calibration of ancient tool-using human history in Australia and elsewhere has come from working out the chronologies of tool evolution.14

Figure 2.2 Locations of some of the earliest known human settlement sites in Australia and New Guinea first occupied at least 40,000 years ago. The lighter-grey shaded area was dry land at the time people first arrived in Australasia from island South-east Asia about 65,000 years ago, when the sea level was about 70m (230ft) lower than it is today.

The Devil’s Lair site in south-west Australia is within a large limestone cave, 5km (3 miles) from the modern coast. The lower parts of the cave are packed with sediments containing evidence for a human presence, including stone tools, bones and – critically for precise age determination in such ancient contexts – charcoal preserved in ancient hearths. The oldest (deepest buried) of these is found almost 3.8m (12ft) below the surface of the cave floor and has been dated to about 45,470 years ago. However, there are other indications of a human presence in layers below this hearth, suggesting that the first human occupation of this cave was at least a few thousand years earlier.15

Limestone caves are also sites of early occupation within the catchment of the Fitzroy River in north-west Australia. The Mimbi Caves include a cave named Riwi in which at a depth of just 65–70cm (25–28in) were found two hearths dated to more than 40,000 years ago. At the Carpenter’s Gap rock shelter, 200km (125 miles) away, the sediment fill is full of well-preserved charcoal, showing that human occupation occurred here about the same time.

Finally, on mainland Australia there is the remarkable discovery of a human skeleton on 26 February 1974 in a sandbank on the shore of Lake Mungo (part of the dry Willandra Lakes system). The body had been laid in a shallow grave, then sprinkled with powdery red ochre before being buried. The first studies to date the bones used various methods and suggested that this man – Mungo Man – died sometime between 61,000 and 62,000 years ago.16 More recent research shows conclusively that this was an overestimate. The earliest unequivocal signs of a human presence in the Lake Mungo area are from sands in which stone flakes – which could only have been created by people deliberately banging one piece of rock against another – are found; they bracket human arrival in the vicinity at between 45,700 and 50,100 years ago.17

The first Australians used fire, burning wood to form ash and charcoal. Some fires were wide ranging, intended to clear woodland of its undergrowth to flush out animals, expose vegetation and stimulate regrowth to which prey animals would then be attracted. Other fires were for cooking, the ubiquitous hearths or fire pits, the remains of which are often found buried within the sediment fills of caves and rock shelters where some of the first Australians once lived. As is the case with the remains of any carbon-rich life form, the age of charcoal can be determined precisely using radiocarbon dating, giving us insights into exactly when a particular tree was alive: often a reliable proxy for the time when the humans who burnt it occupied a particular place.18

As can be deduced from the occupation ages of inland sites discussed above, it seems likeliest that people occupied most of Australia 40,000–60,000 years ago, but there have been suggestions that their arrival was far earlier. The most common type of supporting evidence is that from concentrations of charcoal within long sediment cores from lake beds or the shallow ocean floor, which point to an unusually high incidence of bush fires at a particular point in time, suggesting (yet not proving) the arrival in a landscape of people who burnt the vegetation in order to access food.19

Such an idea was mooted in 1997 for the Queensland coast following analysis of an offshore core,20 but was more famously proposed earlier when sediments from the floor of Lake George, just outside Canberra, Australia’s capital city, were analysed. Lake George is usually mostly dry these days, but its form shows clearly that it was once a lake. A core 72m (236ft) long drilled into its sediment fill allowed scientists insights into its environmental history going back at least 4.2 million years. For our purposes, the critical layer (Zone F) is packed with charcoal – in stark contrast to most of the rest of the core – and was dated as having formed on the lake floor about 120,000 years ago.21 Huge excitement greeted this discovery as commentators interpreted it as implying the first human occupation of Australia to have been far, far earlier than anyone else had hitherto suggested. Yet this age is an outlier among early proposed ages for human occupation of Australia, and for this reason is today widely regarded as wrong. Had it been correct, it would be expected that confirmatory ages from other sources would have since been forthcoming, which is not the case.22

A similar story of early human occupation comes from what is today Papua New Guinea, which was – because of a lower sea level – contiguous with the Australian mainland for most of the time people have lived there. A key site is the Huon Peninsula in the east of the main island. Due to its long-term uplift, this peninsula appears like a giant staircase, each step representing a coral reef that formed at a particular time. Stone axes with distinctive ‘waists’ for easy handling are found in sediments associated with the reef that formed at least 40,000 years ago, showing that people using this comparatively sophisticated technology were present in the area at this time.23

Thus while there is solid evidence suggesting that people were living in Australia and Papua New Guinea 40,000–60,000 years ago, most of the sites where their presence has been detected lie well inland of the modern coast. This seems a bit odd if you forget that, at this time, the sea level was much lower than it is today, so that the Australian coastline would have been much further out to sea. Australia would have been bigger, connected to the main island of New Guinea and closer than it is today to the islands of South-east Asia, from which we know the first Australians came. Perhaps these first settlers started their journeys on the coasts of Borneo or Java, ‘hopping’ by boat from island to island across the straits to reach the Australasian mainland. For this reason we might expect to find the oldest sites in Australasia somewhere in western New Guinea or northernmost Australia.

This inference seems borne out by the early age – perhaps as much as 65,000 years ago – for the occupations at Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, but even these sites would have been significantly inland at the time of first settlement, so that they were likely to have been occupied long after people first set foot in Australia. Just how long the lag was is of great interest – and worth a bit of conjecture. Given that the first arrivals were probably accustomed to feeding themselves from coastal ecosystems, it is plausible to suppose that settlement of the interior did not become a priority for several generations, perhaps only after coastal population densities increased, thereby increasing pressure on proximal food resources. It seems more likely that we are looking at a few thousand rather than a few hundred years, so if we accept that the earliest dated occupations are close to 60,000 years ago, then a time for initial human arrival of 65,000 years ago appears plausible.24

Many of those who have studied Indigenous Australian cultures argue that for most of the time they have existed in Australia, they remained isolated from the rest of the world’s people. In almost every part of the continent, Aboriginal cultural practices and languages show clear signs of having evolved without the outside interference – the cross-cultural syncretism – that can often be so readily unpicked in cultures elsewhere. The reason for the extraordinary isolation of Australian Aboriginal cultures for so many tens of millennia is likely to lie in geographic isolation – and the fact that ocean gaps proved more formidable barriers to potential migrants than they evidently had for the first arrivals. Such inferences have been confirmed by studies of DNA in skeletal remains.25

In 2012, a discovery was made that shook the foundations of the long-held belief in the cultural isolation of Australia. When the first written accounts of Australia appeared in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many made mention of a distinctive wild, pointy-eared dog – the dingo – that was used by Aboriginal people as a hunting companion (although latterly it has become the scourge of sheep herds). At the time of European colonisation of Australia in 1788, the dingo was everywhere on mainland Australia except the offshore island of Tasmania. This observation proved critical to understanding when the dingo arrived in Australia. It could not have been, as was once assumed, as the ocean-going partner of the first human arrivals, for then it would surely have joined them in Tasmania, crossing the Bass Strait land bridge when the sea level was lower than it is today. The last time the ocean rose across the Bass Strait, cutting off Tasmania and its human inhabitants from the rest of Australia, was about 14,000 years ago.26 We can therefore infer that, give or take a few millennia, the dingo was not present on mainland Australia at this time.

This intriguing scenario, which implies that the dingo must have been a significantly later arrival than the first Australians, is borne out by research into dingo DNA. The diversity of this within modern Australia is consistent with the dingo being introduced sometime between 4,600 and 18,300 years ago.27 Put this conclusion alongside another that argues for an episode (well before European contact) of ‘substantial gene flow’ between Australian Aboriginal people and those of the Indian subcontinent, and it is tempting to imagine a small fleet of people and their companion animals (including dingos) sailing south-east from Tamil Nadu, headed perhaps for Sri Lanka or Indonesia, being swept off course and fetching up on Australian shores. While the dingos multiplied in this new land, the human migrants became absorbed into Indigenous Australian cultures, eventually becoming indistinguishable from the original occupants except for the telltale signs in their DNA.28

More is known about a later period of pre-European contact: that between the Aboriginal peoples of northern Australian coasts and the Macassar people of Sulawesi Island (Indonesia), who came in fleets bent on collecting sea cucumbers (trepang) – a delicacy in great demand in China – beginning around 1637. Evidence of their cultural impact comes from the representation in Aboriginal (Yolngu) rock art of the distinctive perahu (vessels) of the Macassar but, despite setting up processing stations for boiling and drying the sea cucumbers, they left little long-term imprint on Aboriginal Australia.29

When we talk of isolation and contact in an Australian context, we need to remind ourselves of scale. The continent is vast, the great majority of its Indigenous peoples remained largely isolated from the rest of the world for tens of millennia, and the local contacts had generally localised cultural impacts; that is, at least, until the arrival in 1788 of the first group of foreigners bent on staying in Australia – the British.

To understand the context, it helps to step back a few hundred years.

It was 13 February in the year 1772 and two French ships – the Fortune and the Gros Ventre – moved cautiously through the morning fog in the southern Indian Ocean when, unexpectedly, land was sighted. This was a cause for celebration, for the ships’ commander, Yves de Kerguelen-Trémarec, had been charged by King Louis XV of France to find the land mass, Terra Australis, which many European thinkers of the time believed lay in the Southern Ocean. The land found by Kerguelen looked bleak and was clearly an island, uninhabited and obviously devoid of the economic possibilities the French hoped Terra Australis might yield for their benefit. But Kerguelen named it after himself and – despite failing to land – confidently declared it an outlier of Terra Australis and hightailed it back to France to report his landmark discovery to his King.30 Delighted no doubt that France had discovered what explorers from other European nations had hitherto failed to find, Louis sent Kerguelen back to his eponymous island to make its link to the fabled southern continent explicit. Unfortunately, no amount of imagination could colour this canvas, and Kerguelen returned to France in 1775, confessing the isolated island to be ‘as barren as Iceland, and even more uninhabitable and uninhabited’, and clearly no continent either, information that incensed Louis and led to Kerguelen’s imprisonment.

Where had this belief in a vast southern continent, Terra Australis, pregnant with economic promise for expansionist eighteenth-century European powers vying with one another to build the largest global empire, come from? As far as we know, the belief originated with the Greek mathematician Eratosthenes who – more than 2,000 years ago – calculated the size of the oikoumenē (inhabited world) to be just one-quarter of the size of Planet Earth. Since the Earth rotates uniformly rather than wobbling, he reasoned, the supposedly heavier continents must be evenly distributed. Thus there must be three other chunks of land of similar size elsewhere on the Earth’s surface that balanced the distribution of land and sea. The southern hemisphere was effectively unknown to classical scholars of this period in Europe, so they made maps showing a vast southern continent (named Antichthones), which they regarded as inaccessible because of the apparent impossibility of traversing the equatorial regions separating it from Europe.

While many such ideas became sidelined in Europe for about a millennium following the decline of the Roman Empire, they were enthusiastically rediscovered by Renaissance thinkers and aspirant explorers between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Some voyages of exploration at this time led to European discoveries of southern lands that were taken as corroboratory evidence of the existence of what became known as Terra Australis. These included the landing on Tierra del Fuego in southernmost South America by Ferdinand Magellan in 1520, the earliest written account of New Zealand by Abel Tasman in 1642, and of course Kerguelen’s incautiously overstated description of his eponymous island in the 1770s.

The shattering of the belief in Terra Australis, and the attendant abandonment of the Greco-Roman belief in Antichthones that underpinned it, came when Captain James Cook anchored the Resolution at Spithead (England) at the end of his second circumnavigation on 29 July 1775 and made haste for the Admiralty in London. Cook reported how his ships had repeatedly traversed the Pacific Ocean, from east to west and from north to south, and had found no trace of a large continental mass answering the description of Terra Australis. The verdict was accepted, and a chapter in the history of European exploration and understanding of the world closed.

Of course, the situation might have been quite different had the continent of Antarctica, which is located pretty much where Eratosthenes placed his Antichthones, been discovered earlier. But the dangerous seas and inhospitable climate in the southern polar regions put off many potential explorers, and it was not until the 1820s that anyone landed on the ice shelf surrounding this frozen southern continent. The realisation that it fringed a huge, ice-covered continent came decades later, by which time all thoughts of the oikoumenē as a serious explanatory tool for understanding the configuration of land and ocean on our planet had been abandoned.

Even though its first recorded circumnavigation took place in 1802 –1803, Australia was never seriously taken to be Terra Australis – it stretched too far north and not far enough south. But for Matthew Flinders in 1814, this was evidently as good as it was going to get, so he named the land Australia. By this time, a British settlement had been established for 26 years at Sydney Cove, today part of Australia’s largest city. Britain had declared Australia to be Terra Nullius (no-one’s land), available for the taking, a ruling used to justify land grabs and the displacement or worse of Indigenous Australians from places their ancestors had occupied for millennia. As is the case with any large-scale cultural contacts, those between Australian Aboriginal peoples and European settlers were varied, but dominated by ones that were confrontational in which the former generally lost out. Yet within the first 100 years or so of European arrival in Australia, there were also instances where settlers learnt to respect Aboriginal peoples’ wisdom and familiarised themselves with it. In several instances this led to written compilations of contemporary Indigenous knowledge, including many of the stories described in Chapter 3.

Colonisation and globalisation both played a role in the subsequent subordination of Aboriginal cultures in Australia, and it is inevitable that much of the traditional knowledge they possessed before 1788 – which had been accumulated over tens of millennia – has been forever lost. Yet the part of it that remains is sufficient to allow the impartial observer insights into the impressive scope and longevity of ancient Aboriginal wisdom, foremost perhaps among that to which we, as a species, have authentic access today.

When we look back in time from the high point that human culture has attained, it is tempting to suppose that our early ancestors lived simple lives, most of which were spent acquiring sufficient food to feed themselves and their dependants, and that they had no time for what we today might describe as leisure pursuits. Half a century ago, this view pervaded much scientific thinking about early human history, but in recent decades there has been ample cause to re-evaluate such ideas. One example is provided by the inescapable conclusion that, as discussed in Chapter 1, the ancestors of the first Australians must have crossed a succession of ocean gaps as much as 70km (43 miles) across in order to reach Sahul (Australasia) from Sunda (South-east Asia). Such trips could not have been accidental or unplanned. To have succeeded, they must have required knowledge of watercraft construction and navigation, and even – you would think – some anticipatory planning for surviving when a foreign shore was reached. Such enterprises required cooperation between people, with particular individuals being assigned different roles. This would have entailed language and a degree of human cognition comparable to our own for people 65,000 years or more ago – something that Western science once viewed as impossible.

Another area in which scientists have traditionally underestimated the ability of our ancient ancestors concerns their artistic abilities. Until the challenges associated with reliably dating rock art were effectively overcome some 25 years ago, claims of its great antiquity were invariably treated sceptically. Yet with the advent of radiocarbon dating using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) techniques capable of determining the age of tiny quantities of carbon, it has been demonstrated that surviving rock art in parts of Africa and Europe was created more than 30,000 years ago.31 Survival is of course key and it undoubtedly requires a particularly fortuitous series of events to preserve rock art this long. In Australia, the oldest dated rock art is a charcoal painting that fell face-down from the ceiling of the Nawarla Gabarnmang rock shelter in Arnhem Land and was then buried beneath cave sediments for 26,913–28,348 years. Mud dauber wasp nests built over the head-dress of a ‘mulberry-coloured human figure’ painted on a rock face in the Kimberley region allowed determination of a minimum age for the artwork of 16,400 years ago,32 the earliest dated image currently known in Australia.

It is, however, certain that earlier Australians created rock art and that this was part of a range of symbolic expression that may even have come with the first arrivals. In support of this, worn ochre crayons made some 40,000–60,000 years ago have been found at both Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, although it is unclear what they were used for. Yet from here it is only a small step towards supposing that, in addition to their maritime and artistic accomplishments, the first Australians used language in a similar way – to celebrate and codify their culture and to accumulate an oral record of their history. It is generally supposed that at most only a few languages would have been spoken by the first Australians (perhaps even just one), but that as time went on and their descendants spread across Australia, the numbers of different languages increased. At the time of the first record, around the start of the nineteenth century, a group of languages known as Pama-Nyungan (PN) was spoken across about 80 per cent of Australia, while non-PN languages were spoken only in parts of its north and north-west.

Such a history of language development and diffusion laid the foundations for Australian Aboriginal cultures to encode important observations of natural phenomena in their oral traditions, and also to develop methods of passing these on from generation to generation in ways that proved both effective and sustainable. While (as we shall see shortly) many observations were recorded in ways that were readily understandable hundreds or even thousands of years later, other observations were mythologised, perhaps because they might otherwise have seemed too implausible – and therefore unimportant – to later generations. Thus was born the Dreaming (Tjukurrpa),33 the rich and varied world of the mind within which Aboriginal people’s culture has long been grounded, and which is believed to exist in parallel with the tangible one and renders the past ‘far beyond the memory of any person, but conserved in the collective memory of the whole community’.34

Before the advent of literacy, the Dreaming of Aboriginal Australians served the same function as a library does for literate people today. It contained ‘books’ that could be read only by those who had been taught to ‘read’ them. Among those books were technical manuals explaining the practicalities of surviving in Australia’s harsh environments, where to find water and food, and how to teach your children and grandchildren to read. Yet in the Dreaming Library were also books of geography that explained the character of the landscapes with which a particular community had interacted and the changes they periodically underwent. These changes might also be recounted in the history texts in the Dreaming Library, emphasis being placed on memorable events that tribal ancestors had witnessed: events that may have included volcanic eruptions, meteorite falls, extreme waves, prolonged droughts and – central to the stories in Chapter 3 – the drowning of once-dry lands along Australia’s coastal fringe.35

Reading a book on the shelves of the Dreaming Library required one to listen to a person who kept the books in their minds. Such people would be those who were older, and who had once been inculcated with this knowledge by their elders. Ethnographic information suggests, quite plausibly, that there were formalised processes in Aboriginal peoples’ cultures for teaching younger people how to read these books and retain the information in their minds, ready one day to pass on to their own offspring. These processes manifest themselves most commonly as adults having a cultural responsibility to pass on the ‘law’ to youngsters. Yet it is clear that in Indigenous Australian cultures there are also inbuilt mechanisms to ensure that the law as transmitted is accurate and complete; omissions or errors in content could have fateful consequences for subsequent generations. Take as an example that a man (A) teaches the law through a series of traditional stories to his son. It is then incumbent on A’s daughter’s son, who is taught the law through a different patriline, to check that his maternal uncle (and his children) has the stories right.36 Such cross-generational checks for accuracy and completeness ensured – as far as possible – that each successive generation had the stories correct and was therefore as well equipped as possible to survive.

The innate conservatism of Aboriginal peoples’ cultures in Australia is also likely to have played an important role in the effective multi-generational transmission of tribal law. Many Aboriginal people expressly state the imperative of telling a story the correct way, something that not only ensures its content is accurate, but also that the ownership of the story (and with it the responsibility to pass it on through the patriline) is made explicit. Particular family lines often have their own stories. While these may be heard by others for whom they are not principally intended, those people do not own these stories and understand that they have no right to retell them.

Many books were read (from memory) out loud, and some were supplemented by performance (dancing and clowning).37 Sometimes the stories in the books were sung, the tunes of the songs prompting the singer’s recollection of the words.38 Rock art was used to reinforce such messages, to be enduring reminders (or mnemonics) of key details from which observers with sufficient base knowledge might then reconstruct the rest of the narrative. Other forms of Aboriginal peoples’ artwork had similar functions;39 an extraordinary map of waterholes in the central desert, initially thought to be a purposeless, solely artistic design, is shown in the colour plate section.40 This map illustrates the purpose of much Aboriginal art – as an essential aid to surviving in a harsh land.

For hunter-gatherers to survive in Australia, particularly through times of more than usual climate-driven stress, they needed to intimately understand the environment they occupied and the full spectrum of livelihood possibilities it represented. Probably this was a lesson Aboriginal societies learnt the hard way – that anything less than intimacy might invite disaster, perhaps in the form of the death of an entire community through starvation or thirst. So the landscape and the climate shaped culture, forcing it to be conservative rather than innovative, and in doing so it ensured that formidable bodies of traditional knowledge – the Dreaming Library – were taught anew to every new generation as comprehensively and as accurately as they had been to previous ones.

The wisdom that underpinned the traditional ways of Aboriginal Australians was something that European colonists of Australia were generally slow to acknowledge.41 Like colonising people in other situations who were certain that their ways of interacting with environments in order to feed themselves were superior to those of the colonised – and who had the weaponry to support this view – most of the new arrivals in Australia after 1788 became contemptuous of Aboriginal knowledge.42 They were resolute in their belief, for example, that the kinds of seasonal interactions with temperate landscapes that had been developed in their native Europe were applicable to Australia. And why should this not be so?

The answer lies in the fact that ‘Australia is the only continent on Earth where the overwhelming influence on climate is a non-annual climatic change’ – the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO).43 This means that for the vast majority of the continent, annual (seasonal) cycles of change are dwarfed by those superimposed by ENSO. When, every three to five years or so, Australia enters an ENSO-negative phase (an El Niño event), drought affects most parts. In the distant past, successions of such droughts were sometimes severe enough to force temporary Aboriginal peoples’ abandonment of Australia’s driest inhabited parts.44 Today they entail water stress on farms, especially within the broad transition zones separating the wetter coasts from the parched interior and, increasingly, water shortages for people in the country’s densely populated urban areas. Conversely, when Australia is affected by an ENSO-positive phase (a La Niña event), things frequently become much wetter than usual; often the dry centre of the continent is given several prolonged soakings, sometime sufficient to bring forth plant life in places where one might otherwise never have suspected it to be lying dormant. From this long acquaintance with the vagaries of the Australian climate, its Aboriginal inhabitants evolved land-use practices and techniques for accessing water that were unfamiliar to European colonists, many of whom inevitably undervalued or ignored them. A couple of examples illustrate the point.

It was natural for many of the earliest Europeans to judge the potential of Australian landscapes for agricultural production through the lens of their experience. One key analogy for some of the earliest British observers of Australia was the presence of the grassland areas along its east coast. On 1 May 1770, James Cook and others made an excursion onshore from HMS Endeavour

… into the Country which we found diversified with Woods, Lawns and Marshes; the woods are free from underwood of every kind and the trees are such a distance from one another that the whole Country or at least a great part of it might be Cultivated [for food crops] without being obliged to cut down a single tree. 45

This view was echoed by Sydney Parkinson, illustrator aboard the Endeavour, who was the first to draw the analogy between this landscape and ‘plantations in a [English] gentleman’s park’.46 As more was written about the Australian landscape, so its remarkable yet puzzling patchwork nature was increasingly remarked upon. In the early 1840s, Henry Haygarth described his discovery of the Omeo (Omio) Plain in Victoria:

The gloomy forest had opened, and about two miles before, or rather beneath us … lay a plain about seven miles in breadth. Its centre was occupied by a lagoon … On either side of this the plain, for some distance, was as level as a bowling-green, until it was met by the forest, which shelved picturesquely down towards it, gradually decreasing in its vast masses until they ended in a single tree … By what accident, or rather by what freak of nature, came it there? A mighty belt of forest, for the most part destitute of verdure, and forming as uninviting a region as could well be found, closed it in on every side for fifty miles; but there, isolated in the midst of a wilderness of desolation, lay this beautiful place, so fair, so smiling, that we could have forgotten hunger, thirst, and all the toils of the road, and been content to gaze on it while light remained. 47

It was not long before more prescient writers came to recognise that these landscapes were human-made, created by Australia’s Aboriginal peoples to provide them with a regular source of food. Writing in 1848, Sir Thomas Mitchell explained it clearly:

Fire, grass, kangaroos, and [Aboriginal] human inhabitants, seem all dependent on each other for existence in Australia; for any one of these being wanting, the others could no longer continue. Fire is necessary to burn the grass, and form those open forests [grassland-savannahs – the gentlemen’s parks], in which we find the large forest-kangaroo; a person applies that fire to the grass at certain seasons, in order that a young green crop may subsequently spring up, and so attract and enable him to kill or take the kangaroo with nets. In summer, the burning of the long grass also discloses vermin, birds’ nests … on which the females and children, who chiefly burn the grass, feed. But for this simple process, the Australian woods had probably contained as thick a jungle as those of New Zealand or America, instead of the open forests in which the white men now find grass for their cattle, to the exclusion of the kangaroo, which is well-known to forsake all those parts of the colony where cattle run. 48

Over tens of millennia, Aboriginal peoples learnt how to manipulate the landscapes of Australia to optimise their food-producing capacity. Within a few decades, in several places European settlers had undone this relationship, seduced by the Arcadian appearance of the grassland savannahs. They paid the price as – it could be argued – modern Australians continue to do today. For Aboriginal burning of the savannahs every few years was not only designed to maintain food supply, but also to avoid much bigger natural ‘burns’. Due to the climatic dominance of El Niño droughts, much of the Australian vegetation catches fire every seven years or so; it has evolved to do so. Yet the size of these natural fires depends on the amount of dry fuel load lying on the forest floor – what Cook called ‘underwood’ – for if there is a lot, the fire will burn fiercely and widely, threatening all living things. Aboriginal people knew this and understood that by deliberately burning these areas every two to three years, underwood would be prevented from accumulating sufficiently to fuel catastrophic bush fires.

Not able or willing to recognise Aboriginal ingenuity, many early commentators on Australia saw instead a people who were neither sedentary nor farmers – the assumed hallmarks of civilised society – so concluded the country to indeed be Terra Nullius (nobody’s land). This provided a legal basis for colonists to drive Aboriginal peoples off lands from which they had subsisted for thousands of years; it was a short-sighted view,49 which failed to acknowledge that nomadism was far better suited to Australia’s environmental and climatic context than sedentism:

Nomadism was clearly an adaptation to tracking the erratic availability of resources as they are dictated by ENSO. Nomadism has a great cost, for possessions must be kept to a minimum. The Aboriginal tool kit was thus rather limited, consisting of a number of usually light, mostly multi-purpose implements. Investment in shelter construction is likewise constrained by such a lifestyle, for there is no point in building large and complex structures when ENSO may [abruptly] dictate that the area be deserted for an unknown period at any time. 50

Land from which Aboriginal peoples were displaced was commonly ‘bought’, then fenced – two alien concepts for Indigenous Australians – and used to graze sheep or to systematically plant crops. It was no longer deliberately and routinely burnt, which opened the door to periodic catastrophic bush fires of the kind that annually raze massive parts of Australia today.51

In addition to fire, water is the other key to sustaining life in Australia. The Aboriginal people of Australia’s deserts not only had maps of waterholes (see colour plate section), but were far better equipped than later settlers to access water where there appeared to be none. One nineteenth-century story recollects that a European travelling through the Western Desert was close to perishing from thirst; ‘at the last gasp, he came to a clay-pan which, to his despair, was quite dry and baked hard by the sun’. He gave up hope, but not so his Aboriginal companion:

… who, after examining the surface of the hard clay, started to dig vigorously, shouting, ‘No more tumble down, plenty water here!’ Struggling to the side [of his companion], he found that he had unearthed a large frog blown out with water, with which they relieved their thirst. Subsequent digging disclosed more frogs, from all of which so great a supply of water was squeezed that not only he and his [companion], but the horses also were saved from a terrible death! 52

Such Aboriginal people were adept at recognising telltale marks made by these water-bloated frogs on the sides of clay pans, in which they might bury themselves for more than a year. Another technique involved stamping on the surface of the clay pan and listening for the faint croaks of the aestivating frogs below its surface.53 Yet despite such time-honoured ingenuity, the search for water by Aboriginal peoples during prolonged droughts was sometimes hopeless.54

We have seen how over the course of perhaps 65,000 years Aboriginal people evolved a fine-tuned understanding of how to live well from Australia’s natural environment.55 Given that the complex, area-specific information – the law – could not expect to be effectively learnt anew by each new generation, Aboriginal Australians formalised instruction that was quality assured, allowing the effective cross-generational transmission of the Dreaming Library. But how long might this knowledge be expected to endure before its essence became obscure?

Probably all of us have had pause to wonder at some point about the apparent superstitions of our parents’ generation or earlier. For me, it was the seemingly meaningless imperatives about never walking beneath a ladder leaning against a wall, or fully expecting days, nay weeks, of bad luck should a black cat cross my path. When I was growing up, I was understandably sceptical, even contemptuous, of such beliefs, but now I wonder whether in fact they might represent legacies of practical advice, once passed down from one generation to the next as a protection from harm. I cannot today comprehend what legacy the ladders and black cats might denote – and I do not believe my parents did – but of course this does not mean that these stories do not represent such a legacy.

Every culture in the world has such legacy stories, many of which – particularly those with spiritual dimensions – have come to define particular groups. In richer societies where global networks dominate the local ones, most such stories are today mere anthropological curiosities. Yet in many poorer parts of the world, where people depend more on local than on global networks, such stories are important keys to unlocking local knowledge. Consider the 3,000 people who live on Savo Island (Solomon Islands, South-west Pacific Ocean), the top third of an active andesitic volcano that has erupted spectacularly three times since ad 1567. The people of Savo have many stories about the precursors of eruption that helped their ancestors evade its worst effects. These stories include the filling with water of the usually dry volcanic crater, an increase in geothermal activity and – intriguingly – the shrinking of the island through wave erosion of the loosely consolidated volcanic sediments produced by the last eruption. The stories tell that once the coastline has been eroded back to the foot of the hills, then another eruption is due – a unique empirical chronometer for eruption recurrence.

From this and many other examples, it is clear that the utility of such stories and the information they contain is context specific. As long as the people of Savo remain on their island, dependent on its abundant natural resources, knowledge of when their way of life is periodically threatened by eruption will be maintained. But as soon as people living on Savo become detached from the local, perhaps through the introduction of imported foods and digital communication networks (as is happening throughout the Pacific Islands), then local knowledge of that kind will inevitably be devalued and replaced by a dependency on external knowledge. This is likely to involve scientific ways of predicting and warning of imminent eruptive activity.

A good example of the enhanced vulnerability of comparatively isolated communities in poorer countries following loss of traditional knowledge for coping with disaster is the smong tradition of Simeulue Island (Indonesia). This tradition teaches that when the ground shakes, people should drop everything and run for the hills, because a massive wave – a tsunami – is likely to soon sweep across the coast. The smong saved countless lives on Simeulue during the great Indian Ocean Tsunami in December 2004, which involved waves of 10m (33ft) high, whereas the death toll along neighbouring coasts where there were no such traditions was far greater. In the aftermath of this phenomenal tsunami, there was a flurry of global interest in improving scientific early-warning systems of such events in order to reduce their human impact. Yet even if that communication were optimal, it would still take at least 15 minutes, probably much longer, from the time of the earthquake to the earliest time people in danger zones could receive the first warning. That would not have been much use on Simeulue in 2004, for the first wave washed over the coastal settlements just 10 minutes after the earthquake was felt. The smong and similar culturally embedded traditions are clearly superior for communities closest to the epicentres of such massive earthquakes.56

For Aboriginal Australians, occupying an ocean-bounded continent in effective isolation from the rest of the world for perhaps 65,000 years, the cultural context may have evolved only very slowly compared to other, less isolated parts of the world. This meant that the content of important stories would not necessarily attenuate in the way it might in more rapidly evolving cultures with more permeable borders. In other words, geographical isolation is key to cultural homogeneity, which in turn nurtures the development of effective and enduring strategies for coping with environmental stresses.

Yet if cultures have been remarkably static in Australia for much of the last 65,000 years or so, the same cannot be said of environments. It is probable that Aboriginal knowledge stories were adapted to environmental change, with the books in the Dreaming Library being periodically revised. Key to this is appreciating how slowly much of this change occurred, giving successive generations of the peoples of the land ample time, you would think, to adapt their stories to the changing conditions.

When we cast our gaze back across the last 65,000 years of our planet’s history, the single most significant event to have occurred in every part of the world was the last ice age. Not only was it cooler than it is today, with the ocean surface being correspondingly lower, but in much of tropical Australia the coldest times of the last ice age were also drier. Already adapted to life on the second-driest continent, many Aboriginal groups evidently found ice-age aridity too much to cope with, for they are known to have abandoned some of the continent’s most arid areas during the coldest and driest part of the last ice age, their former inhabitants clustering into refugia where there was sufficient water and food for them to survive.57

When the ice age ended, Australia’s climate became warmer and wetter, and its inhabitants reoccupied almost every corner of this vast continent.58 It is likely that most of the Aboriginal stories to have survived until today, discussed in the next chapter, were refashioned during this time of climatic amelioration to reflect the new environmental conditions and the concomitant possibilities they presented for human survival. It is also probable that some of the environmental processes that gave birth to these new conditions – like the rise of the ocean surface – became etched into Aboriginal storytelling, an essential element of the law that provided people with a context for understanding the range of new environmental possibilities. It is to these transformative processes that we now turn our attention, one type of which – sea-level rise – is the principal subject of the Aboriginal stories related and analysed in the next chapter.