Australian Aboriginal Memories of Coastal Drowning

One of the most common extant mythical characters in Australian Aboriginal cultures is the Rainbow Serpent, about which innumerable stories have been told and which has been represented in artworks, perhaps most enduringly in rock paintings, for at least 6,000 years. The original Rainbow Serpent came from the sea, and upon occupying the land had many progeny that made it their home.1 Stories about the Rainbow Serpent tell of how it winds its way across the land, wrapping its coils around the hills, shimmying across or beneath the land, furrowing the plains with its sinuous body to create meandering watercourses. At rest, it is often portrayed as the landscape itself, its head and body recognised in the topography. Sometimes it is seen in the sky, whirling and diving, with lights emanating from its body bathing the lands below in a kaleidoscope of colour. The Rainbow Serpent is often portrayed as the guardian of the land, embodying the spirits of the ancestors, the essence of Aboriginal culture, zealous in the stewardship of its integrity, and sometimes visiting a terrible revenge on those who disobey the law.

Its singular form and behaviour have often led to the Rainbow Serpent of Aboriginal storytelling being characterised as a composite being, formed from different parts of real creatures. Yet other research suggests that it is almost an exact representation of the pipefish Haliichthys taeniophorus, or one of the sea horses that might have been among the more striking creatures, least familiar to local inhabitants, to have washed up on the shores of northern Australia when the postglacial sea level ceased rising 6,000–7,000 years ago. It is therefore perhaps no coincidence that this is the time at which Rainbow Serpent imagery appears in Australian rock art in its fullest developed form.2 What such research implies is that oral traditions informed artistic expression that in turn contributes to their recollection.

The idea that the enduring tradition of the Rainbow Serpent in Australian Aboriginal cultures originated with observations of a memorable event (or events) is in keeping with ideas about the origins of many myths – those that are termed euhemeristic. It would be imprudent to claim that all myths are euhemeristic since that would leave no room for human invention, but in recent decades the euhemeristic nature of many myths has become increasingly apparent. As a result, the long-assumed fictional nature of many myths has been challenged. Part of this is due to the impartial scrutiny of particular myths by scientists, especially geoscientists, which led to the demonstration that non-literate cultures had preserved information about certain events and phenomena that science had overlooked, largely because the conventionally admissible evidence appeared fragmented and difficult to reconstruct. Some examples were given in Chapter 1 – those of the Klamath stories about the death throes of Mt Mazama, and of the people of the Sirente about a meteorite fall – but there are many more. They include the linking of the Delphic Oracle in Ancient Greece to surface emissions of hallucinogenic gases,3 geological explanations for abrupt disappearances of islands in the Pacific Ocean basin,4 and even the possibility that sightings of the Loch Ness Monster in Scotland were merely expressions of the effects of strong earthquakes agitating the lake-surface water.5

While Australian Aboriginal cultures differ from many elsewhere in the world in terms of their superior replication fidelity and the longevity of their traditions, the importance of preserving memories to allow future generations to understand their people’s journeys is shared by every cultural group – literate or non-literate. Pre-colonisation Aboriginal cultures were non-literate, yet had rich oral and artistic traditions that provided vehicles for intergenerational transmission of stories. Given that these cultures have been massively altered by the Europeanisation and subsequent globalisation of Australia, we owe much of our knowledge about their original content and depth to

…curious, observant, and relatively unprejudiced individuals in all parts of Australia [who] wrote down descriptions of Aboriginal ceremonies, recorded versions of Aboriginal myths and tales and sometimes gave the texts and even occasionally the musical scores of songs. 6

However abhorrent we might today find the attitudes of many colonising peoples towards the indigenes – not something unique to Australia – we should yet be thankful that such ‘curious’ persons existed, prepared to make an effort to understand and record the wisdom of Aboriginal people before it became diluted or even forever lost. Some Anglo-Australian recorders of Aboriginal stories understood the responsibility they had for proper engagement and accurate recording. One such individual was James ‘Jimmy’ Dawson, who settled in Australia in 1840 at the age of 34 and, while running the Kangatong cattle and sheep station in Victoria, studied local Aboriginal culture. He described his approach in his 1881 book:

Great care has been taken in this work not to state anything on the word of a white person; and, in obtaining information from Aboriginal people, suggestive or leading questions have been avoided as much as possible. The informants, in their anxiety to please, are apt to coincide with the questioner, and thus assist him in arriving at wrong conclusions; hence it is of the utmost importance to be able to converse freely with them in their own language. This inspires them with confidence, and prompts them to state facts, and to discard ideas and beliefs obtained from the white people, which in many instances have led to misrepresentations. 7

Such fine words do not, of course, mean that every Aboriginal story discussed in the rest of this chapter should be uncritically regarded as an authentic Indigenous original – it would be naive to suppose so – or that the rendering of these stories captures all the nuances, indeed all the details, of the original oral tradition. Nor can it be assumed that some stories do not contain an overprint of European thought, imposed either by their Indigenous narrators (who had inevitably had some exposure to the colonisers’ culture) or by non-Indigenous recorders. Yet even with such caveats, the fact that stories from similar locations contain much the same detail suggests that they are reporting much the same thing. And, of course, the fact that stories from at least 21 locations along the coast of modern Australia, measuring some 47,000km (29,200 miles) in length, can be plausibly interpreted in the same way – as memories of a time when the ocean rose across the coastline (and never receded) – strengthens their interpretation as recalling postglacial sea-level rise, an event around Australia that ended about 7,000 years ago.

The world was plunged into the last great ice age about 90,000 years ago. As a result of falling temperatures, in many places evaporated ocean water was precipitated back on to the land in solid form – as snow or ice. Huge ice sheets developed on many higher latitude continental areas, trapping the former ocean water, which resulted in the ocean surface (sea level) beginning to fall. Around 20,000 years ago during the coldest time of the ice age – the Last Glacial Maximum – the global sea level was around 120m (400ft) lower than it is today. Then global temperatures began rising, ice started to melt and much of the water that had been trapped in terrestrial ice sheets began to be returned to the oceans, causing the sea level to start rising. As discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, this process was neither continuous nor monotonic, but for all that it had a massive transformative effect on the world’s coasts – and the peoples who occupied them. For example, one plausible estimate has it that 14m (46ft) of the coastline of northern Australia would have been (laterally) submerged every day during the more rapid periods of postglacial sea-level rise. This was surely something that would have caught the attention of coastal dwellers and made it well suited for recording in oral traditions.

Australia’s Aboriginal stories about postglacial drowning are of two types, what those tireless students of Aboriginal anthropology – Ronald and Catherine Berndt – termed ‘ordinary stories’ and ‘sacred mythology’. The first type are narratives, apparently little embellished, which may describe a time when the sea level was lower than it is today, and the shoreline of a particular part of Australia was consequently further seawards. Such narratives invariably describe what then happened, how the ocean rose, flooding familiar landscapes – places that had names and historical associations for local people – and transforming their environments and their livelihood possibilities. The second type are myths, often alluding to changes to coastal environments similar to those described in the narratives, but explaining these changes in terms of the actions of particular individuals – sometimes super human, more often non-human (like giants or god-like beings with magical powers). Both types of story can be interpreted in the same way. They report a time when the sea level rose across the land, flooding and then drowning it until it came to appear the way it does today.

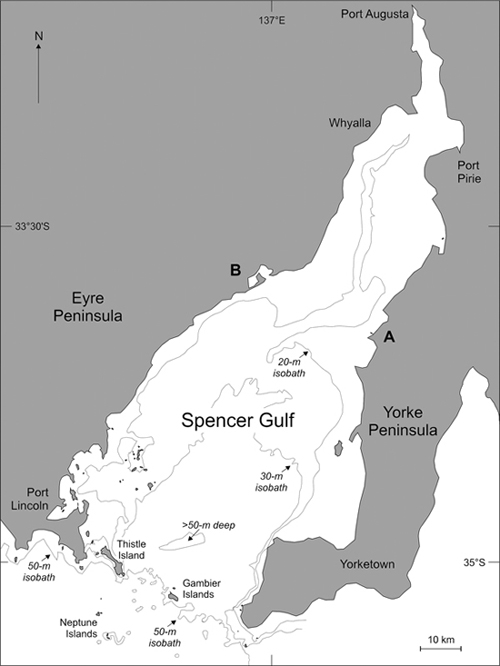

A map showing the 21 locations from which stories or groups of stories have been obtained is shown in Figure 3.1. The descriptions start in the south at Spencer Gulf.

Figure 3.1 The 21 locations along the coast of modern Australia from which Aboriginal stories about coastal drowning have been collected.

On 20 March 1802, four months into the first reported circumnavigation of Australia, Matthew Flinders, an English sea captain, steered his ship Investigator into a ‘gulph’ that was duly explored. Disappointed that this was evidently not the east coast of Terra Australis, that the water at the head of the gulf was as salty as the ocean and that despite abundant signs of habitation ‘we had not the good fortune to meet with any of the people’, Flinders contented himself with naming the place Spencer Gulf, after the First Lord of the British Admiralty at the time the Investigator was commissioned for this voyage.8

The Investigator was being watched. Even if we did not know this, we would consider it likely, of course, but we do know because local people have a memory of this landmark event. The Aboriginal people occupying the western shores of Spencer Gulf – the Nawu – have a story of a beautiful white bird that ‘came flying in from over the ocean, then slowly stopped and, having folded its wings [its sails], was tied up so that it could not get away’.9

Spencer Gulf is a triangular-shaped indentation, 300km (186 miles) in length, along the coast of South Australia, bounded on the west by the Eyre Peninsula and to the east by the Yorke Peninsula. Spencer Gulf is a graben, a fault-bounded depression that has been slowly subsiding for at least a couple of million years. Yet since the rate of subsidence – perhaps less than a tenth of a millimetre a year – is so slow, around a thousandth of the average rate of postglacial sea-level rise, it can effectively be ignored in any consideration of the stories that recall the drowning of Spencer Gulf. The Gulf is comparatively shallow, its floor buried beneath tens of metres of sediment laid down by the rivers that flow into it, as well by the periodic marine incursions – marking the terminations of ice ages of the last few million years – that have affected it. As shown in Figure 3.2, over the 300km length of Spencer Gulf, its floor drops only some 50m (165ft). Thereafter, when you cross its southern lip, the sea floor plunges rapidly downwards.

Figure 3.2 Spencer Gulf in South Australia.

The shallowness of Spencer Gulf – most of it is less than 50m (165ft) below sea level – means that it was dry for tens of thousands of years during the last ice age, for most of which people were living in Australia. Some eyewitness accounts of this time have come down to us today. The stories about a time when Spencer Gulf was dry land are part of the history of the Narungga (or Narangga) people, who have lived for millennia on the Yorke Peninsula. The earliest written account dates from 1930 and tells that the Narungga ‘had a story that has been handed down [orally] through the ages. It is a tale of … when there was no Spencer’s [sic] Gulf, but only marshy country reaching into the interior of Australia’,10 exactly what you might expect if such a low-gradient area of land were emergent today.

The story goes that some groups of the animals that occupied dry-land Spencer Gulf had disagreements with each other.11 The birds in particular ‘felt so superior to the rest of creation that they prohibited the [other] animals and reptiles from drinking at the lagoons’ that traced the axis of Spencer Gulf. Thus, the story continues, ‘began a long conflict in which many were killed, and large numbers of land-dwellers died of thirst’.12 This sounds like an analogy of a human territorial conflict, perhaps exacerbated by a prolonged drought of the kind that often affects Australia during El Niño events.

This situation caused considerable anxiety to the leaders of other groups of animals not directly involved in the conflict – particularly the emus, the kangaroos and the willie wagtails13 – so an eminent kangaroo, after a revelatory dream, was led to a giant magical thigh bone belonging to one of his dead ancestors. He pointed this at the mouth of Spencer Gulf, causing the sea to enter it, then dragging the bone behind him to create a furrow, he walked towards the head of the Gulf. ‘The sea broke through, and came tumbling and rolling along in the track cut by the kangaroo-bone. It flowed into the lagoons and marshes, which completely disappeared’, forcing the animals to live in harmony once more.14 Setting aside the metaphors, it is again plausible to interpret this as an effect of the rising postglacial sea level overtopping the lip, 50m (165ft) below the present sea level, at the mouth of Spencer Gulf, and rapidly flooding its interior, which had the fortuitous outcome of forcibly separating warring tribes.

Flinders knew that the land on either side of Spencer Gulf was inhabited, for he saw smoke from many fires, some even large enough to navigate by, and heard dogs howling at night and possibly even the sounds of human voices. The situation was quite different when he left the area to continue his circumnavigation. His next landing took place on Kangaroo Island, a 4,400km2 (1,700mi2) island some 30–40km (19–25 miles) off the mainland where in contrast: ‘neither smokes, nor other marks of inhabitants’ could he see:

There was little doubt … that this extensive piece of land was separated from the continent; for the extraordinary tameness of the kanguroos [sic] and the presence of seals upon the shore, concurred with the absence of all traces of men to show that it was not inhabited. 15

Kangaroo Island in 1802 was indeed uninhabited, since mainland Aboriginal peoples did not have watercraft that were able to successfully negotiate the often turbulent-water passages separating it from the mainland. They probably also had little inclination to try to reach it, because to the local Ramindjeri people Kangaroo Island was known as Karta – the Land of the Dead – the place to which spirits of the recently deceased travelled. And yet, as has become abundantly clear from scientific studies of Kangaroo Island, it was once home to a sizeable living human population. The earliest hint of this came from studies in the 1930s that identified stone tools scattered around a former lagoon in the island’s south, a discovery that prompted more focused archaeological interest. Several cave and rock-shelter sequences were later analysed that showed people to have been living there at least 16,000 years ago, and probably far earlier, when Kangaroo Island was attached to the Australian mainland during the lower sea levels of the last ice age.

Why, you might justifiably ask, were no people there when Flinders made landfall in 1802? To understand the reason for this, we might note that it was not just Kangaroo Island that was uninhabited at this time, but also many other smaller islands off the mainland (although not large Tasmania). The answer seems to lie in island size and its associated capacity to sustain a viable human population, particularly after sea-level rise caused ocean distances separating particular islands from mainland shores to become too long to be regularly or even easily traversed. At such a point, the islanders would have to have made a difficult decision: decamp to the mainland while they still could, or stay on their island without the certainty that they would be able to retain contact with the mainland. We know nothing of the former, but we do know that some took the second option and stayed put. Whether their descendants all subsequently died on the island, perhaps unable to access sufficient food and water during a prolonged drought, or unsuccessfully attempted to escape its confines, is unknown. However, what is certain from the archaeological evidence is that a once-thriving population on Kangaroo Island had completely disappeared by about 2,000 years ago, leaving ‘a classic mystery story’.16

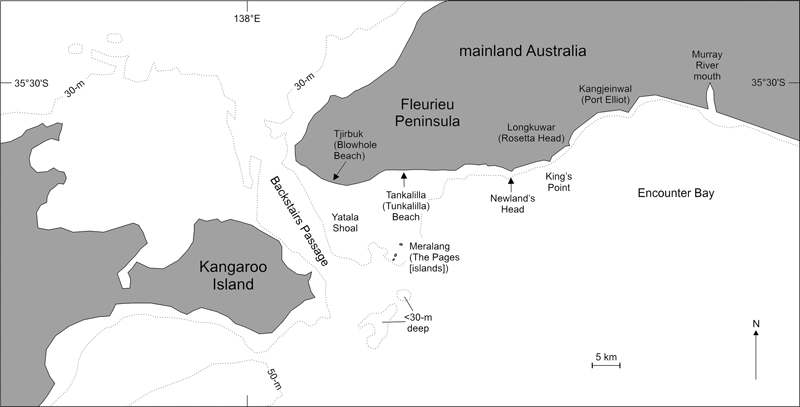

The numerous Aboriginal stories about the drowning of the shortest land connection – named Backstairs Passage – between Kangaroo Island and the Australian mainland (shown in Figure 3.3) all begin with ‘a tall and powerful man’ named Ngurunduri (sometimes Ngurunderi or Nurunderi), an ancestor to many Aboriginal groups in the region who is said to have travelled down the Murray River valley to the coast.17 Ngurunduri had two wives and, in most versions of the story, gave them cause to run away from him.18 With vengeance in mind, he pursued them from the mouth of the Murray River to Kangjeinwal, where he could hear them bathing at King’s Point.19 When he reached King’s Point he saw them at Newland’s Head, and when he reached there he saw them in the distance walking along long Tankalilla Beach. His wives spotted him coming, so began to hurry, intent on reaching the sanctuary of Kangaroo Island, which at that time ‘was almost connected with the mainland, and it was possible for people to walk across’.20 Finally, the two women reached Tjirbuk and, gathering their belongings, began to walk across to Kangaroo Island. When they had got halfway Ngurunduri reached Tjirbuk and, knowing that they sought sanctuary on the island, he roared, ‘Pink’ul’uŋ’urn ‘praŋukurn’ (Fall waters-you).21

Figure 3.3 Kangaroo Island, Backstairs Passage and the Fleurieu Peninsula.

Then the ocean rose, drowning Backstairs Passage, and ‘churned’, drowning the two women and carrying them southwards, where they were turned to stone, forming the Meralang (islands). The larger of these three islands is the older woman, the next in size the other, and the smallest the basket she threw off in a vain attempt to survive. In most accounts, the water rise is portrayed as catastrophic, a ‘terrible flood’ in an 1873 version,22 ‘tempestuous waves’ in another.23 This detail may well have been added as a plausible explanation of how Backstairs Passage – formerly remembered as traversable – became inundated. But its drowning is the key point of all these stories, many of which tell that after Ngurunduri’s wives were literally petrified, he travelled to Kangaroo Island … but not on foot. It seems that because the crossing was now permanently underwater, Ngurunduri dived into the ocean and swam to Kangaroo Island, from which he eventually ascended to Waieruwar – the sky.24

Any route across Backstairs Passage today involves ocean depths of more than 30m (100ft). It might have been possible to cross by walking, wading and perhaps a few short swims when the sea level was 32m (105ft) lower than it is today; the Yatala Shoal, which is less than 10m (33ft) deep today, may have been a critical staging post. Yet it would take a sea level that was 35m (115ft) lower than it is today for a land bridge to be fully emergent here. So the most parsimonious interpretation is that the wealth of Aboriginal stories about the crossing of Backstairs Passage dates from a time in the past when the sea level was this much lower.

Much of the south coast of Australia comprises massive bays formed by an alternation between rocky headlands and long, crescentic sweeps of windswept sandy dune-backed beaches that often impound – except during occasional floods – some of the rivers that sluggishly drain this part of the continent. One such bay is MacDonnell Bay, a place where the land is said once to have extended much further out to sea. There is only one version of the Aboriginal story that describes and explains what happened. It belongs to the Bunganditj people and recounts how this land then appeared: ‘a splendid forest of evergreen trees, including a wattle out of which oozed a profusion of delicious gum, and a rich carpet of beautiful flowers and grass’.25 Unfortunately, the forest was owned by a man who detested trespassers, so when one day he found a woman up a wattle tree stealing gum,26 he told her he would drown her for her crime:

Filled with rage, he seated himself on the grass, extended his right leg towards Cape Northumberland (Kinneang) and his left towards Green Point, raised his arms above his head, and in a giant voice called upon the sea to come and drown the woman. The sea advanced, covered his beautiful land, and destroyed the offending woman. It returned no more to its former bed, and thus formed the present coast of MacDonnell Bay.

If, again, this strikes you as a bit far-fetched, then consider that a bare-bones story about the effects of the rising sea level drowning this coastline may not have been considered sufficiently memorable for oral transmission across many generations. Yet a story with a moral would last much longer, for then storytellers would understand its importance for proper behaviour while listeners learnt that disobedience is inevitably punished.

There is no mistaking this story for a flood story or even the recollection of a giant wave (like a tsunami), for the sea ‘returned no more to its former bed’. This detail, so common in the Aboriginal coastal drowning stories outlined in this chapter, is invariably absent from the flood stories that are part of the oral traditions of coastal cultures in most other parts of the world.

The story from MacDonnell Bay is vague about exactly how much land might have been lost. So if we suppose that it refers to a time when the sea level was 15m (50ft) lower than it is today, then the ‘splendid forest’ might have covered an area of land extending 50–70m (165–230ft) offshore. Alternatively, had the sea level been 50m (165ft) lower at the time of the story, the land might have extended several hundred metres out to sea, perhaps indeed ‘as far as the eye could carry’.

The next stop on our journey around the coast is at the doorstep of Melbourne, one of Australia’s largest cities, which is built around the mouth of the Yarra River. Melbourne is sited where it is because of the proximity of the 1,930km2 (745mi2) almost-enclosed harbour of Port Phillip Bay, which opens today to the Southern Ocean only through a narrow 2km (1¼ mile) wide passage (The Rip). In the heyday of cross-ocean trade, long before Australian cities were connected to one another by road, the shelter afforded to ships by such an extraordinary place was valued hugely (Figure 3.4).

The skeleton of Port Phillip Bay developed millions of years ago, when land was uplifted along the seaward side of what was then a sizeable coastal inlet, effectively blocking it off from the sea; on the western side the Bellarine Peninsula is a horst, an upthrust block, while along the southern and eastern sides successive phases of movement along the Selwyn Fault produced the Nepean and Mornington Peninsulas respectively. Enclosed and with several rivers debouching into it, over time Port Phillip Bay has become choked with sediments, mostly washed down by rivers but supplemented with wind-blown material and, particularly in its southern parts, marine sands washed in by waves. Yet when the sea level dropped during the last ice age, Port Phillip Bay – which is no deeper today than 25m (82ft) below sea level – dried out. The rivers cut channels through the exposed sediments and found their way to the sea. When the sea level rose once more after the last ice age ended, some of those former outlets became plugged by massive amounts of sediment, so that even when the ocean surface had risen above the level of the floor of Port Phillip Bay, it remained dry. Later, of course, the sea forced its way through at least one of those sediment plugs – that is where The Rip is today – and flooded the Bay, but it is also possible that subsequently it became blocked again and Port Phillip Bay dried up once more, even though the ocean surface was higher than its floor.27

Compared to many other accounts, most Aboriginal stories describing how Port Phillip Bay appeared when it was dry and how it was later inundated are matter of fact and apparently unembellished, suggesting that they may recall exactly such a comparatively recent drying-up event. Alternatively, such stories might recall the time when the rising postglacial sea level did drown the Bay, a memory that was reinforced by a more recent such event.

Figure 3.4 Port Phillip Bay.

In 1841, Georgiana McCrae, daughter of the 5th Duke of Gordon, moved from her native Scotland to Port Phillip (as Melbourne was then known), and four years later built a house in the shadow of a granite monolith – Arthur’s Seat – at the southern end of the Mornington Peninsula. By displaying ‘friendly curiosity and an unusual willingness to understand tribal customs’ of the resident Bunurong Aboriginal people, McCrae – an inveterate diarist – was able to record a wealth of information, peppered with verbatim quotes, about their way of life and their stories about Port Phillip Bay.28 She wrote:

The following is an [Aboriginal] account … of the formation of Port Phillip Bay: ‘Plenty long ago … men could cross, dry-foot, from our side of the bay [in the east] to Geelong [in the west].’ They described a hurricane – trees bending to and fro – then the earth sank, and the sea rushed in through the Heads, till the void places became broad and deep, as they are today. 29

A decade or so later, on 9 November 1858, in his submission to a Committee of the Legislative Council enquiring into the condition of Aboriginal peoples, one William Hull recalled that various Aboriginal groups ‘say that their progenitors recollected when Hobson’s [Port Phillip] Bay was a kangaroo ground – they say “plenty catch kangaroo and plenty catch opossum there”’, a condition that could have obtained only if the Bay was dry land. Hull went on to add that his Aboriginal informants had told him that ‘the river Yarra once went out [to sea] at the Heads, but that the sea broke in, and that the Bay became what it is [today]’.30

Another historical recollection was collected in the 1950s and recalled that in pre-European times, the Aboriginal people at Dromana were accustomed to cross dry Port Phillip Bay to hunt at Portsea and Queenscliff; in doing so, they had to ‘walk a little, swim a little’.31 And then there is a mythical story handed down among the Kulin Aboriginal people which explains that

…Port Phillip was once dry land and the Kulin were in the habit of hunting kangaroos and emus there. One day the men were away hunting and the women had gone off collecting roots and yams, while some young boys, who had been left behind, were playing in the camp. They were hurling toy spears at each other, just like their fathers did. In the camp there were some wooden troughs full of water, and one of the spears upset one of these … this was no ordinary bucket, but a magic one, and it held a tremendous amount of water, which came rolling down engulfing all the land. 32

In order for Port Phillip Bay to become dry, the sea level outside The Rip would have to be at least 9–12m (30–40ft) lower than it is today.

East from Port Phillip Bay and Melbourne lies the coast of Gippsland, the closest part of the mainland to Tasmania, today Australia’s largest offshore island. Gippsland is a low-lying region also characterised by alternating rocky headlands and long sandy beaches. It lies along the northern side of Bass Strait, which for much of the time people have lived in Australia was dry land – the Bassian Land Bridge – that allowed people and animals to move freely between the two. The postglacial sea-level rise is known to have progressively drowned this land bridge, the last tenuous connection being severed about 14,000 years ago, thereafter consigning the people of Tasmania (and islands in the Bass Strait) to progressively increasing isolation from their mainland cousins.33

Along low-lying coasts like that of Gippsland, the effects of the postglacial sea-level rise would have been particularly dramatic, so it is unsurprising that there is an Aboriginal story recalling them. The story belongs to the Kurnai people and recalls that

…long ago there was land to the south of Gippsland where there is now sea, and that at that time some children of the Kurnai, who inhabited the land, in playing about found a turndun [a musical instrument], which they took home to the camp and showed to the women. ‘Immediately,’ it is said, ‘the earth crumbled away, and it was all water, and the Kurnai were drowned.’ 34

Unwittingly the Kurnai children had broken an important taboo, for the turndun was only for men’s use; its discovery by children and handling by women invited retribution. Like enduring oral traditions in many cultures, the use of retribution as an explanation of why things happen is common in Aboriginal cultures, probably because adults felt an ethical imperative to pass on morality stories to their young that would not have been applicable to neutral ones.

Since there is just the one story from Gippsland and since it is so vague about where the coast once stood, we can only speculate about this and the associated level of the sea. If we assume that the story recalls a time when the shoreline lay some 50m (165ft) seaward of its present position, then the sea level might have been around 20m (65ft) lower. If the Gippsland shoreline was 100m (330ft) further out, then the sea level would have been closer to 50m lower than it is today. This information is key to estimating minimum ages for such stories, something that is explained at the end of Chapter 4.

From Gippsland, we head up the east coast of Australia to Botany Bay, the place where Captain James Cook first landed on 29 April 1770, which is now part of the sprawling city of Sydney. The description of Botany Bay by Joseph Banks, naturalist on Cook’s voyage, was so glowing that 18 years later it was the place where Governor Arthur Phillip was instructed to establish Britain’s first penal colony in Australia. It did not take Phillip long to realise its unsuitability for this purpose – its marshy foreshore, and the lack of fresh water and a secure anchorage – so he swiftly shifted the nascent penal colony to Sydney Cove, one of several bays that eventually became the settlement of Port Jackson. We are left to wonder why initial reports about Botany Bay were so wrong. Consider the experience of Captain Watkin Tench, whose books about the first four years of the Port Jackson settlement are among the most informative from that era. Criticising Banks and the other ‘discoverers of Botany Bay’ for noting that its fringes were ‘some of the finest meadows in the world’, Tench noted that ‘these meadows, instead of grass, are covered with high coarse rushes, growing in a rotten spungy [sic] bog, into which we were plunged knee-deep at every step’.35

Yet despite such an unpromising description, Botany Bay has a Aboriginal story, owned by the Dharawal people, that talks about how the Bay formed as a result of sea-level rise. It tells of a time long ago when the Bay was mostly dry land, the floodplain of the Kai’eemah (today’s Georges River). So grateful were the Dharawal for having such a fine place to live that one day the decision was made to travel into the hinterland to give thanks to the Creator Spirit for this. The younger members of the community were not happy at the prospect of travelling into such ‘rough land’, so in the end only the ‘knowledge holders’ went, leaving a warrior named Kai’mia behind to look after the others. After several days, huge waves washed into the mouth of the Kai’mia, ‘destroying much of the swampland … used for food gathering’. Fleeing inland, Kai’mia and the youngsters were pursued by giant waves, eventually taking refuge in a cave. Kai’mia tried persuading his charges that they should give thanks to the Creator Spirit for having saved them, but one retorted that they now had nothing to be thankful for – ‘the waves have taken away what we had’. Then the cave collapsed, burying all its occupants except Kai’mia, who crawled away to die, his trail of blood marked by the flowering of the Gymea Lily – a plant with blood-red tips. When the knowledge holders returned, they followed the trail of the Gymea Lily back to the cave, but were too late to rescue those buried inside. Sadly, they ‘returned to their homeland to find that what they had known was no longer. Instead of the swamps, there was a great bay, and where the Kai’eemah had met the sea there was [sic] high mountains of sand’.36

Today, Botany Bay has been transformed beyond recognition – Sydney’s airport is located on its shore – so the most reliable guide to its original form is the chart made by Captain Cook in 1770. This shows that the entrance to Botany Bay was then 5–9 fathoms deep, a range of 9–16m (30–50ft), the depth at which the ocean surface would need to be for Botany Bay to be dry land – as the Dharawal recall it once was.

The bay just south of Botany Bay is Bate Bay, where ‘Mister’, perhaps one of the last of the Gunnamatta Aboriginal people who once occupied the area, passed on his reminiscences in the 1920s. One of his stories was about how ‘in the early days the sea was a lot further out, and his people used to gather ochre there’, at a place he identified as being about 4km (2½ miles) east (seawards) of Jibbon Headland.37 If the ‘4km’ is taken literally, the modern ocean depth here is about 50m (165ft); more likely, the stated measure was unintentionally vague, perhaps much less than 4km, so the depth to which this memory refers is more likely 5–20m (16–65ft) below today’s ocean surface.

Further north from here, off the mouth of the Brisbane River, lie two elongate islands – Moreton and North Stradbroke in English, Moorgumpin and Minjerribah respectively pre-colonisation. Moreton and North Stradbroke Islands are formed predominantly from sand, typically a ‘bedrock’ of hard indurated dune sand overlain by a veneer of younger unconsolidated sand, all of it deposited along the shores of these islands by waves that had carried it from the south. During the last ice age, when the sea level was lower than it is today, these islands were joined to the Australian mainland. Therefore at the time of the earliest evidence for their human occupation – about 20,000 years ago at Wallen Wallen – no cross-sea journeys were required. Yet by about 7,000 years ago, the sea level had risen so much that both islands were effectively cut off from the mainland, and their inhabitants thereafter developed traits distinct from their mainland counterparts.

The Aboriginal people who live on Moreton Island are known as the Nughi, those in the northern parts of North Stradbroke as the Noonukul, and both groups are part of the Quandamooka nation. Stories about times in the past, when the geography of these islands was quite different from what it is today, include both mythical and factual varieties. The sole known representative of the former comes from a time when the two islands were one. It involves a Noonukul man named Merripool who had the power to control the winds, something he carried around in a magic bailer shell.38 Envious of such power, the Nughis plotted to steal this shell, but Merripool was informed of their plan and

… called the four winds to come to him … He called for many days and nights and his voice became louder and louder … [until] the winds blew so hard that they caused the water to cut Moorgumpin [Moreton] away from Minjerribah [North Stradbroke].39

In a detail that perhaps expresses the ecological consequences of separation, the story continues by saying that when the animals on Moreton Island realised what was about to happen, they all moved to North Stradbroke Island, leaving the Nughi people on Moreton Island solely dependent on the sea for their food.

Evidence of a factual memory of a time when Moreton and North Stradbroke Islands were apparently not as far apart as they are today comes from the account of Mary Ann, an Aboriginal woman who was interviewed in 1907, when she was ‘very old’, and who remembered that when she was young ‘a small island’ existed between the two on which ‘bopple bopple’ trees grew.40 She also recalled that at the time the Noonukul elders could themselves recall a time when the people of North Stradbroke Island might converse ‘quite easily’ across the gap with the Nughis on Moreton Island.41

On 17 May 1770, Captain James Cook gave the world the first written account of these islands. He named the bay in which they are found Moreton Bay, noting in his journal that the land forming the islands he ‘could but just see it from the top mast head’. Interestingly, he did not record there being two islands here and it is possible that at this time the islands were joined, forming a continuous strip of land.42

Sand islands are notoriously changeable in form and many periodically merge or become severed from their neighbours because of changes in the amount of sand being supplied to their shores by waves – rather than any change in the sea level. So while the stories about Moreton and North Stradbroke Islands are certainly intriguing, they do not necessarily require – as do most other stories related in this chapter – the sea level to have been lower than it is today. That said, we know that the islands were connected when the sea level was lower 9,000 years or so ago, so perhaps the possibility that these stories are recollections of that time should not be too hurriedly dismissed.43

In a similar vein, the next places along the Australian coast for which there is an Aboriginal tradition of a time when islands were not islands are Hinchinbrook and Palm Islands, off the central Queensland coast. Hinchinbrook and Palm Islands are quite different, with the former being much larger than the latter and much closer to the mainland. Palm Island today lies about 25km (16 miles) offshore. The people of this area have a story about a distant ancestor of theirs named Girugar, who travelled across the area giving key places the names by which they are still known and – most critically for our purposes – walking across to Hinchinbrook and Palm Islands (and nearby islands) without getting his feet wet.44 The only way that this could be accomplished would be if the ocean surface were at least 22m (72ft) lower than it is currently.

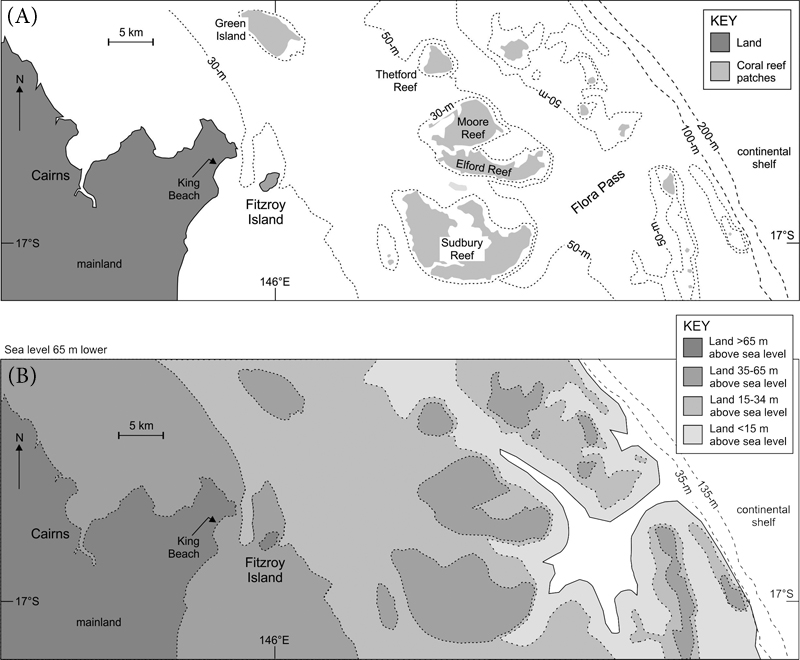

In his 1980 opus The Languages of Australia, Robert Dixon, an indefatigable recorder and analyst of Aboriginal languages, noted how ‘many tribes along the south-eastern and eastern coasts [of Australia] have stories recounting how the shore-line was once some miles further out; that it was – on the north-east coast – where the [Great] barrier reef now stands’.45 Inscribed on the World Heritage List, the Great Barrier Reef – the only living thing on Earth that is visible from outer space – lies off the east coast of tropical Australia. Around its southern extremity its outer edge is some 200km (125 miles) offshore, but farther north, in the area around Cairns, this is a mere 40km (25 miles) seawards of the modern coast. As shown in Figure 3.5, the ocean floor between the modern shoreline and the reef edge is comparatively shallow, with patches of reef separated by deeper water passages. Drop the sea level a few tens of metres and these patch reefs become hills and the intervening passages become valleys, a gently undulating landscape that would have terminated during the last ice age 20,000 years ago in sheer cliffs – today’s reef edge – around the base of which the waves would have crashed resoundingly.

Cairns is built on the traditional lands of the Yidinjdji people, who also claim title over much of the submerged land extending to the edge of the Great Barrier Reef, for many parts of which they have names and about which they know stories. The most widely reported story about coastal drowning in this area was first written down between 1892 and 1909 by the Reverend Ernest Gribble, when he was in charge of the Yarrabah mission station. Gribble wrote of the tradition concerning a man named Goonyah, who by catching a forbidden species of fish angered the ‘Great Spirit’ Balore. In an attempt to drown Goonyah and his family, Balore caused the sea to rise. The humans fled to the mountaintops, where they heated large stones and rolled them down the slopes, something that checked the advance of the rising waters; ‘the sea, however, never returned to its original limits’.46 A later version of this story, collected in the vernacular (Yidin) language by Robert Dixon, also included the detail that the Yidinjdji had tried in vain to stop the unwanted rise of the ocean across the lands on which they had long depended for sustenance.47

Another story collected from the Djabuganjdji (Tjabogai-tjanji) people in the late 1920s from Double Island, just north of Cairns, recalls a time ‘when the coral reef was all scrubland’ and a blue-tongued lizard, of the kind common in eastern Australia, ‘travelled to the edge of the deep dark waters and caused the sea to bubble up till it covered the reef and arrived at its present position’.48

Echoes of the time long ago, when the area between the modern coastline around Cairns and the edge of the barrier reef were 40km (25 miles) or so away, are also found in the names of places in the Yidin language.49 Key is that the Yidin word for island is daruway, which also means ‘small hill’. The Aboriginal name for Fitzroy Island is gabar, which means ‘lower arm’, a reference to the time when it was a mainland promontory enclosing a river valley. There was once an island named Mudaga halfway between Fitzroy Island and King Beach, named for the pencil cedar trees (Polyscias murrayi) that grew there when it was emergent. Finally, the Yidinjdji recall a time when Green Island was formerly four times larger than it is today, something that would be expected were the sea level lower.

Figure 3.5 Cairns and the Great Barrier Reef, today (A) and during the last ice age (B).

For Green Island to have been four times larger than it is today, the sea level might need to be 5–10m (16–33ft) lower, but Fitzroy Island could not have been the ‘lower arm’ of a mainland promontory unless the sea level was at least 30m (100ft) lower. Yet if we accept the stories about the Great Barrier Reef being dry or even ‘scrubland’, the sea level would need to have been 40–50m (131–165ft) lower. And if indeed the Aboriginal people of the area knew a time when the shoreline was where [the edge of] ‘the barrier reef now stands’, then this would have to have been when the sea level was a staggering 65m (210ft) lower than it is at present.

Our next stop along the Australian coast is on the shores of its largest indentation, the Gulf of Carpentaria. During the last ice age, when the sea level was more than 120m (400ft) below today’s level, this part of Australia was connected to New Guinea to the north. At the centre of the land bridge lay a great freshwater lake – Lake Carpentaria – around which the people and animals of the area flocked.50 The rising sea level after the ice age ended saw the progressive inundation of this land bridge, the eventual conversion of the freshwater lake to the saltwater gulf, and the appearance of islands within the Torres Strait that today separates Australia from Papua New Guinea.51 The progressive submergence of this well-populated land bridge would of course have driven many groups of people outwards to seek new land from which they might subsist.

The languages spoken by Aboriginal groups in most parts of Australia around the time of its European colonisation all belong to the same language family (Pama-Nyungan), which is thought to have spread across most parts of the continent some time within the past 3,000 years or more. What is key for our purposes is that this dispersal appears to have originated somewhere around the now-submerged land bridge between Papua New Guinea and Australia, and it is plausible to suppose that its outward spread from here was driven by sea-level rise. Some corroboration of the precise and quantifiable linguistic argument may be found in Aboriginal stories about ‘lost lands’, now-submerged homelands from which ancestral mainland populations came. The geographical details about where these homelands were located are typically vague, but one that is told by the Yolngu people of eastern Arnhem Land, who occupy part of the western shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria, states that the ancestral land named Bralgu was located ‘somewhere in the Gulf of Carpentaria’, perhaps therefore a direct memory of the translocation of people from part of the submerging land bridge.52

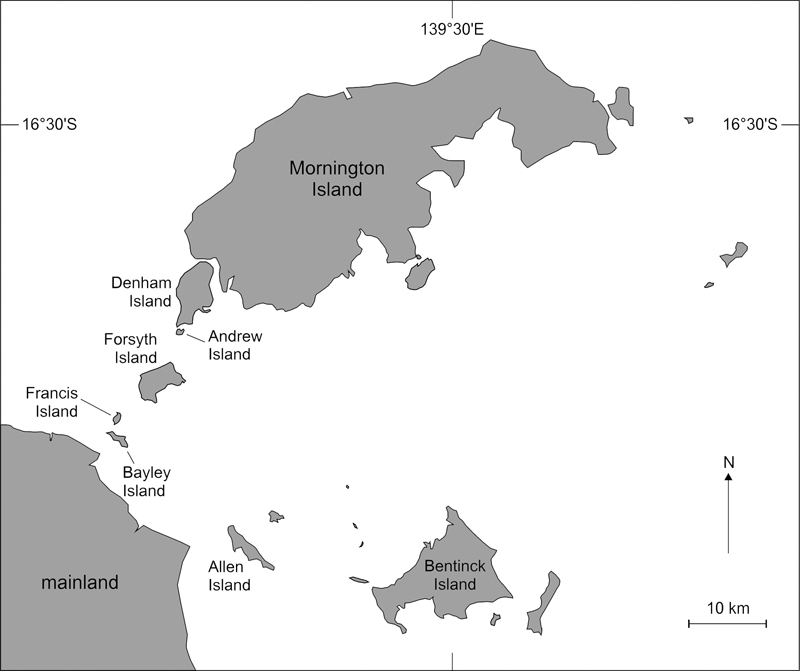

Our focus is on islands lying off the coast within the modern Gulf of Carpentaria, principally the Wellesley Islands (Figure 3.6), which would have formed only after the sea level rose across the former mainland fringe. The earliest written version of the oral tradition was produced by Dick Roughsey of the Lardil people in the early 1970s, who explained that:

In the beginning, our home islands, now called the North Wellesleys, were not islands at all, but part of a peninsula running out from the mainland. Geologists … thought that the peninsula might have been divided into islands by a big flood which took place about 12,000 years ago. But our people say that the channels were caused by Garnguur, a sea-gull woman who dragged a big walpa or raft, back and forth across the peninsula. 53

The Lardil also remember that the Balumbanda, one of their clan groups, originally came from the west along that peninsula before it was ‘cut up into islands’.

Figure 3.6 The Wellesley Islands, southern Gulf of Carpentaria.

Later research focused on Lardil stories dated to more than 5,000 years ago, about how channels formed that isolated the Wellesley Islands from the mainland.54 A fuller version of the Garnguur (kankurr) story told by Roughsey explains that the seagull woman sought to punish her brother Crane for failing to look after her child, so she dragged her large raft back and forth across the land that connected Forsyth Island to Francis Island until the deep-water channel (more than 10m/33ft deep) that exists there today was formed. The sweet-potato woman, Puri, who was fleeing from Crane, is said to have created the passage (named purikal) between Forsyth and Andrew Islands. The narrow channel between Denham and Mornington Islands is said to have been created by a shark panicked by lightning.

The sheer number of channel-cutting stories here suggests that the gradual submergence of the land connection between the Wellesley Islands and the mainland was witnessed by people who found the process so disruptive, so literally life-changing, that it became a conspicuous element of their oral traditions. Yet for a land connection to be re-established, it would only be necessary for the sea level to be 5m (16ft) lower, although a 10m (33ft) fall would see the peninsula reappear. Exactly how sea-level changes affected human settlement of these islands – something that is key to understanding how old the stories might be – is as yet uncertain. While it is likely that people occupied the area during the last ice age when the ‘islands’ were contiguous with the mainland, we cannot be sure whether people stayed on the embryonic islands as the rising sea level was starting to separate them from the mainland – which is what some channel-cutting stories suggest – or whether they retreated to the relative security of mainland shores at this time. There is evidence favouring both views.55

Moving west from the Gulf of Carpentaria we come to the north-facing coast of Australia, much of which is called Arnhem Land. Perhaps because it is further north than almost every other part of the continent, it has a wealth of Aboriginal traditions and stories that are likely to be some of the earliest in Australia. The four groups of drowning stories in this area all involve offshore islands – Elcho, the Goulburn group, Cape Don and the Tiwi (Bathurst and Melville) Islands. It is perhaps no coincidence that such stories are found predominantly along the coast of Australia where the continental shelf exposed during the last ice age was widest – and where, consequently, the subsequent rise of the sea level was most noticeable. One authority estimated that during this period ‘on the gently sloping northern plains [of Australia] the sea inundated five kilometres of land annually’.56 Not only is this kind of change blatant, but its effects on the way people lived, what they could eat and with whom they had to compete for food and territory undoubtedly left enduring marks on the contemporary evolution of Aboriginal societies in this part of Australia.

Elcho Island is separated from the mainland today by a narrow strait that would be passable, albeit circuitously, were the sea level 5m (16ft) lower than it is today, and fully emergent if the sea level were 10m (33ft) lower. Two extant stories about such a time are known, one about an Elcho resident named Djankawu who tripped while walking along the beach, accidentally thrusting his walking stick into the sand and ‘causing the sea to rush in’.57 The other tells of the Ancestresses, magical beings who, whenever they needed to cross to Elcho, made a sandbar that vanished once they had completed their crossing.58

Further west off the Arnhem Land coast lie the Goulburn Islands, comprising South Goulburn (Warruwi) and North Goulburn (Weyra). One story, which is perhaps an echo of the time when Warruwi was joined to the adjacent mainland, concerns a man named Gundamen who wanted to cross from the latter to the island. Afraid of the deep water, he was helped by a woman with magic powers who called out ‘mubin, mubin, murbin!’, which caused a land bridge to emerge just long enough for him to cross.59 Another story is more detailed and recalls a time when only a small creek named Mandurl-mandurl separated Warruwi from Weyra. The creek teemed with fish, and the local people would set their nets (yalawoi) in it overnight and pull them up full in the mornings. For all this, a man named Gurragag rarely succeeded in catching any fish in Mandurl-mandurl, so one day he cut down a huge paperbark tree (waral). It fell into the creek with such an enormous splash that seawater poured in, creating the ocean gap between the two islands that is today some 7km (4½ miles) wide.60 If such stories recall a time when these islands were in fact closer to the mainland and to each other, then the sea level would have to have been 17–20m (56–65ft) lower than it is today.

The people of coastal Arnhem Land ‘possess names for and maintain intimate knowledge of places far out at sea that are known to have been above sea level 10,000 years ago’, an extraordinary yet undeniable fact that has become the basis for a large-scale marine-protection strategy for this part of the Arafura Sea.61 For example, the inhabitants of the Goulburn Islands know of two submerged islands – Lingardji and Wulurunbu – thought to be the sites of shoals about 20km (12 miles) east of Weyra that now lie in waters 9–11m (30–36ft) deep. How could these people have such intimate knowledge of a submerged landscape unless their ancestors had once walked across it, witnessed its submergence and consigned their memories of it to posterity?

Moving west along the coast of Arnhem Land, we come to Cape Don, the western extremity of the Cobourg Peninsula, which has been occupied by the Arrarrkbi peoples for tens of thousands of years. They have stories about how one group of their ancestors once occupied an offshore island named Aragaládi that is now underwater. One story tells that a sacred rock (maar) on the island was accidentally bumped one day, causing so much rain to fall that the island became submerged: ‘children and women were swimming about … [they] had no canoe to enable them to cross over in this direction to the mainland at Djamalingi (Cape Don) … trees and ground, creatures, kangaroos, they all drowned when the sea covered them’.62 This story perhaps combines memories of large waves like tsunamis and their effects on coastal peoples in this area with the story of an island being submerged, a common situation with similar oral traditions in the island groups of the Western Pacific Ocean.63

There is another story about the disappearance of Aragaládi that is more entwined with other oral traditions of Arnhem Land Aboriginal peoples, particularly that of the Rainbow Serpent. For this story has Aragaládi as part of a giant snake, one of its coils conveniently (and intentionally) raised above the ocean for people to live upon. But when its inhabitants knocked the maar, the snake drew its coil underwater, swallowing all the people: ‘she made the place deep with sea water. Those first people became rocks. Nobody goes to Aragaládi now.’64

The Mayali people, who now live inland east of the Alligator River (see Figure 3.7), also have a tradition that the first people in this part of Australia – the Nayuyungi – came from the sea between the Cobourg Peninsula and the Goulburn Islands. This is also possibly a distant memory of an inhabited island that was submerged by postglacial sea-level rise, compelling its inhabitants to relocate to the mainland.

The key point here is that along the Arnhem Land coast, likely to be the longest continuously inhabited part of Australia, as well as the one with the broadest continental shelf to be drowned by postglacial sea-level rise, there are numerous extant stories (and probably many more forever lost) that tell of islands off the coast that were once inhabited but are now submerged. This is just what would be expected in such a geographical situation that experienced rapid sea-level rise over several millennia, yet it is impossible to know the minimum depth that the sea level would have to have been in order for these islands to have been emergent. If we assume, without any real evidence, that Aragaládi Island was once the shoal some 150km (93 miles) east of the Cobourg Peninsula, then the sea level would have had to be 9–15m (30–50ft) lower than it is today for habitable land to be exposed there.65

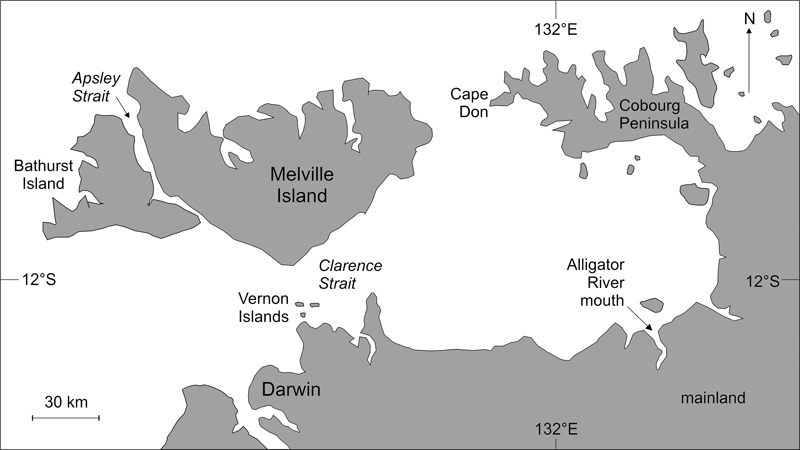

The next stop on our tour of the Australian coast is a group of sizeable offshore islands – the Tiwi Islands – where traditions tell of the apparent isolation of their populations as the sea level gradually rose. Better known as Bathurst and Melville Islands (Figure 3.7), they lie a minimum of 25km (16 miles) off the Australian mainland near the northern city of Darwin. It is to the water gap known today as Clarence Strait that Tiwi stories about the apparent cutting off of these islands from the mainland refer.

Figure 3.7 Location of Bathurst and Melville Islands (the Tiwi Islands), Cape Don and the Cobourg Peninsula.

The stories begin in the Tiwi ‘time of darkness’, before Bathurst and Melville were ‘born’ as islands, a time when the land ‘contained no geographical features, animals or humans’.66 Then, from within the earth – meaning from what may have been becoming the mainland (rather than the islands) – came an old blind woman named Mudangkala (or Murtankala), who crawled with her three children along what is now Clarence Strait until they reached Melville Island. Critically, water followed the group as it moved northwards: ‘the flow of water continued to increase and is today known as Clarence Strait … [Mudangkala] continued to move over the land known as Bathurst Island till finally water flowed on to form what is now known as Apsley Strait’.67 These stories may be memories of one of the last significant human migrations from the Australian mainland to the Tiwi Islands, the references to blindness perhaps signifying the uncertain nature of Mudangkala’s destination, and those to crawling indicating the difficulty of crossing a partly submerged land bridge.

For anyone in the past attempting to travel from the mainland to the Tiwi Islands without the use of watercraft, the Vernon Islands (Potinga to the Tiwi people) would have been key ‘stepping stones’. One Tiwi story recalls that the Vernon Islands were once attached to the southern part of Melville Island at a place called Mandiupi, but then, ‘as a result of an earthquake in the distant past’, the connection was broken.68 Such a story illustrates the issue of the plausibility of oral traditions well. In order to expect a tradition – like the instinctively improbable ‘breaking-off’ of islands – to be duly repeated through future generations, it may need some explanation. Not associating the story with a sea-level rise, perhaps the storyteller added the detail about an earthquake simply to make it credible. For an earthquake could not possibly have caused the Vernon Islands to break off from Melville, but a rising sea level would have swamped the connection, giving the same apparent result.

Other aspects of Tiwi society, from its language to its uncommon matrilineal society, make it distinct from mainland Aboriginal societies, something that is ascribable to physical and cultural isolation imposed by postglacial sea-level rise.69 In addition, there are various aspects of Tiwi Island terrestrial ecosystems that also point to the effects of isolation.70 So for how many years have the islands been isolated, and how long is it since Mudangkala made her last desperate crossing of Clarence Strait? We have to wait until the end of Chapter 4 for a precise answer to these questions, but for now it seems that isolation would have occurred when the ocean around the Tiwi Islands was at least 12m (40ft) lower than it is today, a time in the past when – through a combination of walking, wading and short swims – it would probably have been possible to reach them from the mainland. When the sea level was 20m (65ft) lower, it is likely that someone could have crossed without getting their feet too wet, although the likely route would have been tiresomely circuitous.71

Moving further west into north-west Australia, it is surprising, given this region’s demonstrably long history of Aboriginal occupation and its extraordinary legacy in rock art (throughout the Kimberley and Pilbara regions in particular), that there are not more stories about coastal drowning here than there are. In fact, there is just the one group of stories – about Brue Reef (discussed below) – but there are also two intriguing studies that demonstrate the massive impact which postglacial sea-level rise had on the Aboriginal inhabitants of this region.

The first of these studies concerns the baobab tree (Adansonia gregorii), which is native to north-west Australia as well as parts of Africa. In Australia it is usually called the bottle tree, and for thousands of years it has been prized by savannah-dwelling Aboriginal groups for food, medicine and shelter from the sweltering conditions in which it thrives, typically from the coast to the desert fringes. Parallel lines of research into baobab gene flows and into the routes along which the various words for baobab among Aboriginal groups passed allow it to be plausibly shown that these trees, once confined to the (now-submerged) continental shelf of north-west Australia, were probably carried inland and intentionally dispersed as the sea level rose in this area.72 The clever idea behind this scenario is that the oldest (genetically less diverse) types of baobab are found along the coast, where the people also have the fewest words for the tree (and its component parts). Further inland there is greater genetic baobab diversity and a far greater range of names for the tree. These two observations suggest that people living with baobabs along the now-drowned continental shelf, recognising their great value, carried their fruit pods with them as they were gradually forced inland by the rising waters. In addition to deliberately planting the baobab inland, they also introduced it to inland Aboriginal groups that, quickly convinced of its value, dispersed it even more widely.

The second study used Aboriginal rock art to plot the course of postglacial sea-level rise in the Dampier Archipelago (Murujuga). The earliest rock art here dates from the time during the last ice age when the sea level was so low that today’s islands were part of a mountain range some 160km (100 miles) inland from the coast. With the rise of the postglacial sea level, the area was gradually transformed – from inland to coastal to offshore islands – but the people stayed put, adapting their livelihoods to the changes that the sea level (and climate) imposed on them. They recorded these changes in their rock art that is fortuitously etched through a veneer of rock varnish into the weathered surfaces of the gabbro and granophyre boulders that are scattered about the Murujuga landscape in vast numbers. They look like scree but have in fact weathered out of the underlying bedrock in the places where they are found now, unmoved for perhaps millions of years. Thus, the rock art dating from when the area was far inland shows examples of inland fauna like macropods (kangaroos and wallabies), but in the rock art from the time the shoreline had reached the area, engravings of fish and other sea creatures are dominant.73

Stories about Brue Reef are well known among the Bardi and Jawi peoples of the Kimberley coast.74 Lying about 50km (30 miles) off the mainland and uncommonly isolated, Brue Reef is said once to have been a habitable island named Juljinabur; today it is awash at high tide. The gist of the various stories is that Juljinabur was inhabited by a person called Jul and his greedy kinfolk (munjanggid), who had become cannibals. One day, in fruitless pursuit of a turtle, a Jawi family from Tallon Island (Jalan), 100km (60 miles) to the south, found themselves drifting in a swift current (lu) towards Juljinabur. To save the Jawi family from being eaten, Jul hid the people on the island for a few days, and when his kinsfolk’s attention was diverted, sent them back to Jalan in a double-hulled canoe (inbargunu). Unfortunately, the munjanggid got wind of what had happened, and there was a big fight that precipitated the sinking of the island and its conversion to the inter-tidal reef it is today.

For a community sufficiently large to be organised and competitive to have lived on Brue Reef, this 12ha (30 acre) island would have had to be at least 4m (13ft) above the ocean surface. Such a vision becomes altogether more believable if we suppose that the sea level at the time Jul and his predatory kin lived was perhaps 10m (33ft) lower than it is today.

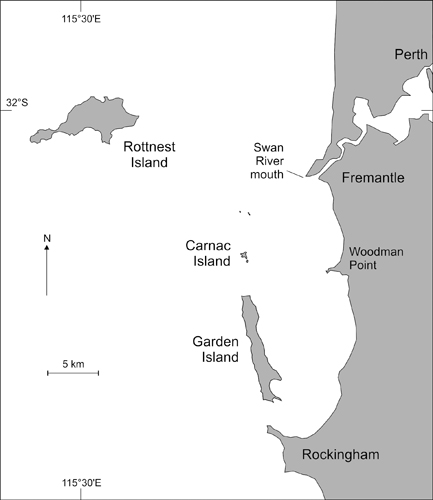

We now move down the coast of Western Australia to the city of Perth, founded in 1829 on the banks of the Swan River, the traditional land of the Noongar people. Off its mouth lie three islands – Rottnest, Carnac and Garden – that are said once to have been connected to the mainland (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8 Off the mouth of the Swan River, Western Australia, lie the islands of Rottnest, Carnac and Garden.

There appears to be just one extant version of this story, although it has been repeated numerous times in different contexts. It is a good example of the narrative type of story, and was in fact recorded merely as part of an appendix in George Fletcher Moore’s 1884 Diary of Ten Years Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia, which – notwithstanding its gung-ho title – amply demonstrates the author’s sympathetic understanding of Aboriginal culture. The story goes

… that Rottnest, Carnac and Garden Island, once formed part of the mainland, and that the intervening ground was thickly covered with trees; which took fire in some unaccountable way, and burned with such intensity that the ground split asunder with a great noise, and the sea rushed in between, cutting off these islands from the mainland. 75

It is probable that Moore, ‘a religious man of strong convictions’ according to his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, spiced up the original narrative; the image of the ‘ground splitting asunder with a great noise’ has biblical resonance and is probably not an authentic detail of the Aboriginal story. Yet the bare fact of these islands – Rottnest is now some 20km (12 miles) offshore – having once been part of the mainland is something that is consistent with many other stories discussed in this chapter for other parts of the Australian coastline. So how might it ever have been so?

As for Kangaroo Island and several other islands off the Australian mainland, it has long been known that people lived on Rottnest (or Wadjemup) – the largest and highest of the three islands – in pre-colonial times, yet it was uninhabited at the time of the first written accounts of it. The first estimate of the date of the earliest human occupation of Rottnest was based on measurements of the ages of land-snail shells within ancient sand dunes burying artefact-bearing soils, and was calculated as being in excess of 50,000 years ago – and perhaps as long ago as an improbable 125,000 years. As is often the case, recent research has established a more probable time for the formation of the artefact-bearing soils as between 10,000 and 17,000 years ago.76 Were this the case, then Rottnest would not have been an island but would have been attached to the mainland because of the lower sea level. The reason why Rottnest had no Aboriginal people living there at the time of European colonization of Australia is probably similar to those of its offshore islands. Either a residual population stayed there after the island was cut off from the mainland and died out because of a lack of resources and its inability to survive periods of extreme weather, particularly drought on limestone Rottnest, or the place was abandoned as it was becoming an island because its inhabitants feared a future in isolation. Justifiably so.

If we accept the detail in the story that Moore recorded about the land connection being ‘thickly covered with trees’, it does suggest that it was well above the high-water mark and perhaps significantly beyond the reach of sea spray. This condition would be adequately met were the ocean surface 10m (33ft) lower than it is today, although a narrower, meandering land connection between Rottnest and the mainland would also have existed when the sea level was just 5m (16ft) lower than it is today.

Around 15km (9 miles) off the south-west corner of Australia lie two prominent rocks. Named the White-topped Rocks, perhaps because they are plastered with seabird excrement, they are a well-acknowledged aid to navigation in these sometimes unsettled waters. There is a single Aboriginal tradition, perhaps collected as early as 1844, about these rocks that goes as follows:

… in those olden days there was a large plain extending from the main land out to the White-topped Rocks, about nine miles [14km] out from Cape Chatham. On one occasion two women went far out on the plain, digging roots. One of the women was heavy with child, and the other woman had a dog with her. After a while they looked up, and saw the sea rushing towards them over the great plain. They both started running towards the high ground about Cape Chatham, but the sea soon overtook them and was up to their knees. The woman who had the dog picked it up out of the water and carried it on her shoulders. The woman who was advanced in pregnancy could not make much headway, and the other was heavily handicapped with the weight of the dog. The sea, getting deeper and deeper, soon overwhelmed them both, and they were transformed into the White-topped Rocks, in which the stout woman and the woman carrying the dog can still be seen. 77

The critical omission, common in giant-wave (tsunami) stories, that the sea did not subsequently retreat from the land it inundated, implies that this story may also be an authentic memory of coastal drowning in this area. If this is indeed the case, then for the sea floor between the mainland and the White-topped Rocks to have been dry, the sea level would need to have been 55–60m (180–200ft) lower than it is today.

The next example, further to the north-east, comes from Oyster Harbour, a tidal inlet with a narrow, deep entrance – a smaller version of Port Phillip Bay (described earlier) – which is shown in Figure 3.9.

Figure 3.9 Oyster Harbour.

The story comes from Captain Collet Barker, an army officer who in 1829 became commander of the military settlement at King George Sound, now the town of Albany. Barker was an energetic recorder of Aboriginal place names and traditions, in which context he recorded the only known such story about the origin of Oyster Harbour.78 It begins with a woman going into the ‘bush’ to search for food and calling out to her husband, who was sitting by their cooking fire. When she found a particular type of snake, a ‘Quoyht’ as rendered by Barker, the man was happy, but when she returned empty-handed, her stomach full of this great delicacy, he became enraged. He struck her, broke her leg, then ran away:

She becomes sick & dragging herself along in the line where the King’s River now runs, reaches Green island, where she dies … Her body became putrid & an easterly wind setting in is smelt by a dog at Whatami ... He follows her track & arrived at the place, commences scratching, which he continues so long that he digs a great hollow & the sea comes in & forms Oyster Harbour.

Like the story relating to Port Phillip Bay, this one may echo events far more recent than the period of postglacial sea-level rise – but it may not. It may simply be that the narrow entrance to Oyster Harbour became blocked, as such narrow gaps often do, as a result of which the inlet dried up, a situation that might have continued for so long that local people regarded it as normal. Then, perhaps during a storm, the entrance was breached and the ocean poured in. Alternatively, it might be more like the situation at Spencer Gulf, where the rising sea level overtopped the entrance to a lowland, perhaps marshy area, and flooded it rapidly.

In the first, more conservative scenario, the sea level would not need to be any different from today’s, but it would have to have been at least a few metres lower for the latter to be true; an ocean surface 4–10m (13–33ft) below its present level would adequately account for the progressive flooding of the area, and the formation of the inlet and its later submergence.

The next story is very similar, reflecting the prevalence of coastal inlets with narrow entrances along this part of the Australian coast. At Bremer Bay, a brackish-water lagoon named Wellstead Estuary is blocked at its seaward entrance by a barrier beach, a thick plug of sand through which water can slowly seep, but which effectively prevents the ocean from reaching the estuary and vice versa. Many such barrier beaches formed when the sea level was rising after the last ice age, with waves driving sand into massive heaps at the heads of bays like Bremer Bay. Such barriers can endure for thousands of years, and in some parts of the world they have long been populated. Parts of iconic Cape Cod in Massachusetts, USA, for example, where many houses are built on unconsolidated barrier beaches, are likely this century to experience ‘widespread and catastrophic destabilization … resulting in significant land losses and salinization of freshwater environments’ as a result of sea-level rise.79

Similar to today, at the time of the Aboriginal story about Bremer Bay there was ‘a large shallow lake not far from the sea’. The local people were spearing so many fish there that the birds were going hungry, so their leaders – the willie wagtails – implored Marget, a water spirit, to help. Innately indolent, Marget declined to assist, so

… a number of the Willy Wagtails got a long, slender stick, and drove it into one of the mud springs near the lake … The stick slowly sank in the ground … and disappeared, but they got another thicker stick and put it on the top, and did the same thing over again. This time the bottom stick touched the sea which ran under the lake and the water gushed up and ran into the lake.

Stirred into action by the birds’ initiative, Marget went to their aid so that ‘the sea bubbled and roared through the hole in the lake made by the long sticks’. But the people were not deterred by what had happened, so the willie wagtails again pestered Marget, ‘who made the hole bigger … and the sea roared in harder than ever, making the lake overflow’, which caused people to flee the area.80

Barrier beaches are occasionally breached, invariably re-forming subsequently, so the existence of a sizeable plug of sediment at the entrance to Wellstead Estuary today is no proper measure of either its longevity or its stability. Such breaches may occur during floods or storms, and certainly do not require a sustained change in ocean level. That said, the details in this narrative about there having once been a lake into which the sea roared are consistent with the sea level rising above a particular threshold and entering for the first time an area of low ground, occupied perhaps by a freshwater marsh that local people valued as a source of sustenance. A sea level around 3m (10ft) lower than today would have rendered such a scenario true.

Almost at the end of our circumnavigation of Australia, we now move east again to one of its most forbidding coasts, that of the Nullarbor Desert.81 The word Nullarbor is not an Aboriginal one, but derives from Latin and means ‘no trees’, still an accurate characterisation of the appearance of this extraordinary landform that covers a bit over 2,000km2 (772mi2), about the size of Kansas, USA, or England and Scotland combined. The limestone geology of the Nullarbor surface tells us that it was originally a part of the ocean floor that, around 14 million years ago, was pushed upwards above the ocean surface. Exposed for the first time to the agents of subaerial weathering and erosion, especially wind, its surface irregularities became smoothed and it began to look as it does today – a vast, flat, treeless plain stretching as far as the eye can see in every direction.82 Except south.

The southern fringe of the Nullarbor, where it meets the sea in the Great Australian Bight, forms a spectacular set of steep cliffs 50–90m (165–295ft) high, which – in most places – drop to the edge of the ocean itself. There is no coastal flat, just pockets of fallen rocks waiting to be pulverised and removed by the waves that smash relentlessly into the bases of these cliffs, causing them – over many hundreds of years – to slowly recede. The only significant exception to this along the 800km (500 mile) length of the Nullarbor coast is the Roe Plains, a low coastal flat that affords us a glimpse of how the area looked when the sea level was lower during the last ice age.83

Aboriginal people have occupied the Nullarbor for tens of millennia, their societies evolving a resilience to the harsh conditions that few others could emulate. The Wati Nyiinyii (or Zebra Finch) people of the Nullarbor have a tjukurrpa (oral story) that tells of an old man journeying through the desert, deliberately uprooting every mallee eucalypt tree he comes upon. This was something that threatened the survival of the entire community, for Aboriginal people wanting to drink would often dig up part of the long roots of the tree, and chop them into short lengths before draining the water they contained into bark containers: a practice that would not kill the tree yet would slake their thirst.84 Uprooting a mallee was reckless, and in the story all the water that was lost as this perverse old man continued on his way drained into the ground, just what happens in limestone country, ‘creating a huge flood to the south’, where the Nullarbor cliffs lie. The Wati Nyiinyii were obliged to travel en masse to the coast at Eucla to try and stop the encroaching flood:

The Wati Nyiinyii then pour over the Eucla escarpment, rather like an army of ants … Once the Wati Nyiinyii reach the sea, they begin bundling thousands of spears to stop the encroaching water. These bundles were stacked very high and managed to contain the water at the base of what is today the Nullarbor (or Bunda) cliffs. 85

This story may be a recollection of a time when the sea level was lower and a great plain, now covered with ocean, stretched out from the base of the Nullarbor cliffs. As the sea level rose, local groups like the Wati Nyiinyii could not fail to see what was happening: ‘individuals thirty years old might have lived through the destruction of a mile [1.6km] of their coastal territory’.86 Searching for an explanation they sought, as is common, one involving inappropriate life-threatening behaviour that deserved retribution. Yet so concerned were the Wati Nyiinyii at the loss of land that they may have attempted various practical and supplicatory responses, the former including construction of a wooden fence (with spears used as pickets) to try and halt the ‘encroaching water’ at the cliff foot.

Given the imprecision of the story and the comparatively gentle slope of the sea floor beyond the Nullarbor cliffs, it is difficult to know how far offshore the shoreline might have been at the time when the Wati Nyiinyii first noticed it moving landwards. Were the sea level 10m (33ft) lower, the shoreline would be several kilometres further south here; were the sea level 50m (164ft) lower, the shoreline would lie tens of kilometres off the modern shoreline.