CHAPTER ONE

TECHNO CITY; OR, DUDE, WHERE’S MY AIRCAR?

Joh Fredersen’s eyes wandered over Metropolis, a restless roaring sea with a surf of light. In the flashes and waves, the Niagara falls of light, in the colour-play of revolving towers of light and brilliance, Metropolis seemed to have become transparent. The houses, dissected into cones and cubes by the moving scythes of the search-lights gleamed, towering up, hoveringly, light flowing down their flanks like rain.—Thea von Harbou, Metropolis (1927)

They glided down an electric staircase, and debouched on the walkway which bordered the north-bound five-mile-an-hour strip. After skirting a stairway trunk marked “Overpass to Southbound Road,” they paused at the edge of the first strip. “Have you ever ridden a conveyor strip before?” Gaines inquired. “It’s quite simple. Just remember to face against the motion of the strip as you get on.” They threaded their way through homeward-bound throngs, passing from strip to strip.—Robert Heinlein, “The Roads Must Roll” (1940)

Commuting is going to be lots more fun in the future.

Where now we trudge wearily on crowded sidewalks, we’ll ride cheerfully along on slideways. Now we squeeze into crowded, squeaky trains with old chewing gum under the seats, but soon we’ll enjoy shiny silent subways that shoot passengers to their destinations with a pneumatic whoosh. We’ll no longer need to time dangerous dashes across intersections crowded with heedless automobiles when soaring sky bridges connect nearly topless towers. Forget freeway traffic jams—airspeeders will lift us off the pavement as they careen along skylanes that interweave among the towers.

These images are familiar from paintings, movies, and other visualizations of future cities. Artists know that one of the best ways to give a touch of “authenticity” to a science fiction cityscape is to fill the skies with personal flying machines. Aircars figure in the early tongue-in-cheek SF film Just Imagine (1930), in Blade Runner (1982), where the cops tool around in VTOL Spinners, and The Fifth Element (1997), where Bruce Willis is an aircabbie. If viewers thought the car chase through the streets of San Francisco was exciting in Bullitt (1968), how about an airspeeder chase through the airways of Coruscant in Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002)?

Cities are vast and complex machines for moving things around, and science fiction often suggests that movement will be slicker in the future. The idea that air avenues and air boulevards might seriously supplement or supplant surface streets goes back a century plus, to balloon ascensions, blimps, and the first powered flight. A flying car maneuvering through skyscraper canyons is an instantly recognizable sign that we are in the world of the future, and one that is especially vivid for readers and moviegoers in mundane cities whose skies are clear except for distant jetliners, occasional TV station news copters, and new law enforcement drones. Nearly a century ago, Hugo Gernsback included an aeroflyer in Ralph 124c 41+, introducing a relatively straight ancestor of George Jetson’s bubble-top aerocar. Predictions of personal flying vehicles were a post–World War II staple for Popular Science, Popular Mechanics, Mechanix Illustrated, and other hobby magazines that combined real science, exciting speculation, and home projects.1 By the end of the twentieth century, the nostalgic lament that “It’s 199- [or even 20--] and where’s my aircar?” was a meme that infected syndicated columnist Gail Collins, the Tonight Show, and the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes.

Some parts of the science fiction future have already happened. We have personal communication devices and voice recognition software, much like what fourteen-year-old Arcadia Darell used to do her home work in Isaac Asimov’s Second Foundation (1953). Smart phones do more tricks than Star Trek flip phone communicators. Imaging devices peer deep into the human body and send data to experts half a globe away, and we are working toward Dr. Leonard McCoy’s medical tricoder. Entire libraries pop up on our screens in a few keystrokes. Twenty-first-century cities have elevated people movers and monorails (not very successful), intercity maglev trains, and even occasional subdivisions built around airstrips—if not a Cessna in every garage.

The television series Futurama used science fiction clichés to satirize American society and popular culture. Among its most common features were aircars and air scooters, here ridden by Turanga Leela and Philip J. Fry. An aircar featured prominently in the show’s opening credits, swerving through the skies of New New York and crashing into a giant video screen displaying the name of creator Matt Groening. Courtesy Fox Broadcasting/Photofest © & TM Fox Broadcasting.

It is striking how easily aeroflyers fit into visions of urban futures. We don’t need to imagine cities radically transformed, but rather places that function much as they do now, but with a bit more zip and pizzazz. Aircars will be taxis and commuter vehicles and family sedans. They’ll chase criminals through the streets and engage in drag races. Because aircars are machines that instantly signal “future,” they are also tempting targets for satire. Episodes of Futurama (1999–2013), the American cartoon series from Simpsons creator Matt Groening, opens with an aircar careening wildly through the high-rise canyons of New New York before crashing into an animated billboard showing snippets of twentieth-century cartoons. The world of New New York in the year 3000 includes hover cars, pneumatic tubes rather than wheeled vehicles, wiseass robots, and spaceships that take off directly from the roof of the Planet Express headquarters, all in the interest of lampooning American culture, Star Trek, and the whole idea of better living through mechanical devices.2

MODERN AND MODERNE

Aircars are a prime feature of Techno City, my term for the future metropolis stocked with straight-line Popular Mechanics projections that imagine technological innovations and experiments as the everyday future … and as everyday, nonrevolutionary parts of such futures.3 Techno cities are places that work, where society and government have adopted and adapted to new technologies. Indeed, they often seem to work much the same way as the places where we already live. They have public and private transit and utility networks. They have hotels, shopping malls, government buildings, and neighborhoods. They have climate-controlled buildings with secure entry systems—now that retinal and fingerprint recognition locks are available in real time, perhaps it will be DNA recognition that opens the dilating door.

Techno City is often simply background for a story whose plot interest is elsewhere, an example of the framing technique that Robert Heinlein famously developed in the late 1930s and 1940s by inserting references to new technologies and customs into descriptive passages without offering elaborate explanations. These are obviously science fiction cities, reached by space travel or projected into the future—but their look and feel can be quite homey. They are like regular cities with enough new gizmos and spicing of technological change to signal that we are in a different time-place. Of course you get from one hotel floor to another with a bounce tube—how else would you do it? Of course newspaper pages turn themselves—hardly worth more than a passing nod of attention (especially since the pages of my daily paper now turn themselves on my iPad).

Here is an example from Heinlein’s story “The Roads Must Roll,” first published in Astounding in 1940 and widely anthologized as a Golden Age classic. The action takes place along the Diego-Reno roadtown, a vast moving highway that links the Los Angeles-Fresno-Stockton-Sacramento corridor. The “road” is a set of parallel moving slideways that step up from five miles per hour at the edge to a hundred miles per hour at the center. Using power from Solar Reception Screens, the United States has developed conveyor roads to save the nation from the unsustainable costs associated with maintaining 70 million automobiles (for perspective, the nonfictional United States actually had more than 250 million registered vehicles in the early twenty-first century). Solar-powered factories flank the roads and are flanked in turn by commercial districts, and then housing that is scattered over the surrounding rural landscape.

After this quick sketch, Heinlein drops his interest in the “city” part of roadcities. The plot involves a wildcat action by road maintenance technicians for the Stockton segment. Adherents of a radical worker ideology, they shut down the road, causing havoc among thousands of commuters. The federal officials who control the roads under the auspices of the military retake the Stockton office and quash the strike. The narrative choices met the expectations of Astounding readers, with attention to the physics of slideways, celebration of the disinterested engineer, and a slam at organized labor—a hot-button issue only five years after the organization of the CIO in 1935 and three years after the success of its controversial and technically illegal sit-in strike against General Motors.

Had he wished, Heinlein could have developed roadcities more fully. As early as 1882, Spanish designer Arturo Soria y Mata had proposed using railroads as the spine of what he called Cuidad Lineal, an idea that he illustrated with a scheme for a fifty-kilometer ring city around Madrid and a proposal for a linear city from Cádiz to St. Petersburg. The highly eccentric Edgar Chambliss advocated for a Roadtown from the 1910s to the 1930s, conceiving it as a row of Empire State Buildings laid end to end on top of an “endless basement” for service conduits. He got a friendly hearing from New Deal officials but no serious take-up.4 Meanwhile, Soviet planner Nikolai Miliutin in the 1930s suggested decentralizing industry in exurban corridors sandwiched between roads and rail lines and flanked by housing; the result was to be industrial efficiency, easy commutes for workers, and elimination of invidious class distinctions between center and periphery—a sort of urban industrial version of King Arthur’s round table. A decade later, Le Corbusier sketched a similar sort of linear industrial city (without acknowledging any predecessors).5

The idea resurfaced in the United States after World War II as automobiles began to draw tightly centered downtowns outward along highway corridors. Journalist Christopher Rand in 1965 suggested that Los Angeles had a spine rather than a heart, commenting that the Wilshire-Sunset axis rather than downtown functioned as the urban core. He was channeling architect Richard Neutra, who soon after arriving in Los Angeles from Europe sketched “Rush City Reframed,” consisting of traffic corridors lined with slab high-rises—quite like the unfortunate Robert Taylor Homes that would march alongside Chicago’s Dan Ryan Expressway from 1962 to 2007. The thought experiments have kept on coming, such as the Jersey Corridor Project of Princeton University architecture professors Michael Graves and Peter Eisenman, proposed in 1965 at the start of their high-profile careers. Living in what was beginning to emerge as the Princeton area Edge City, they suggested bowing to the inevitable by connecting Trenton to New Brunswick with two parallel megastructures sandwiching and surrounded by strips of green, since “a linear city is the city of the twentieth century.”6

The urban ordinary is a pervasive foundation through Heinlein’s work in the 1940s and 1950s. The protagonists in “The Roads Must Roll” stop for a meal at Jake’s Steakhouse No. 4, which comes complete with crusty proprietress and two-inch slabs of beef. In The Door into Summer, written in 1956, he projected protagonist Daniel Boone Davis thirty years into his future from 1970 to 2000. Because Heinlein’s interest was time travel paradoxes, he depicted a Los Angeles that still worked pretty much the same as the twentieth-century city, but with some new laws and customs. In Double Star (1956), guests in the Hotel Eisenhower do indeed use bounce tubes rather than elevators, but the hotel rooms are numbered by floors, just like twentieth-century hotel rooms.

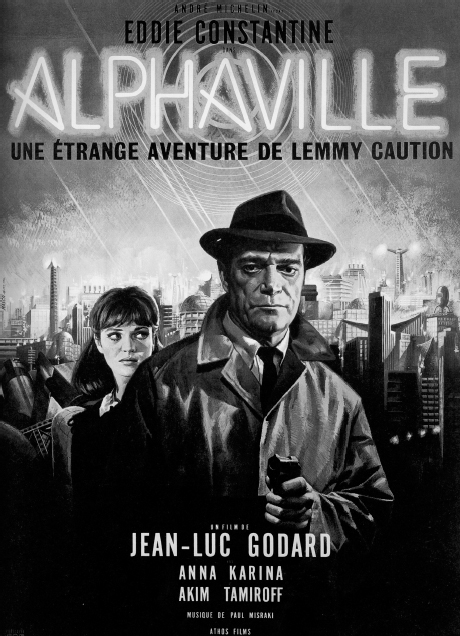

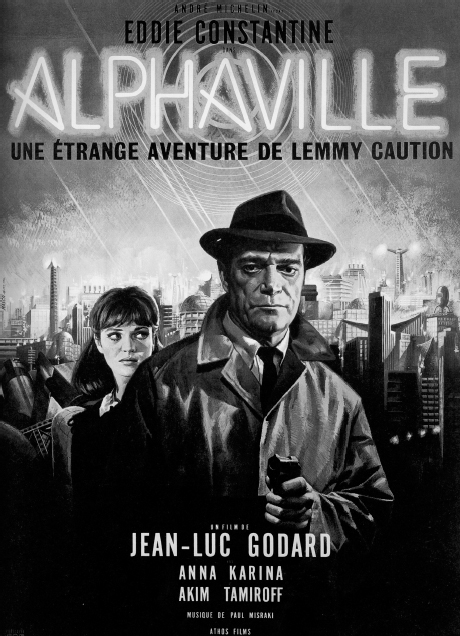

The urban ordinary is also a powerful presence in films set on near-future Earth and Earthlike places, where the “shinier” parts of the contemporary cityscape stand in for cities to come. Jean-Luc Godard used the high-rise towers of the brand-new La Défense district of Paris to represent an extraterrestrial city in Alphaville (1965). Office buildings and shopping malls in Los Angeles and Washington, DC, are the 2054 future in Minority Report (2002). Contemporary Los Angeles plays the role of future cities in In Time (2011), and LA and Irvine office buildings stand in for the mid-twenty-first century in Demolition Man (1993). In Total Recall (1990), portions of Mexico City do duty as a city of 2084.

These cinematic choices show the lasting cultural resonance of the art moderne and streamlined styles of the mid-twentieth century. Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition in 1933 and the New York World’s Fair of 1939 used similar architectural rhetoric to signify progress during the troubled times of the Great Depression. In the midst of postwar prosperity, the organizers of the Century 21 Exposition in Seattle in 1962 made the same choices—the Space Needle is a kissing cousin of New York’s Trylon and Perisphere. The aesthetic road took one fork to the glistening aluminum-and-glass skyscrapers of the 1950s and 1960s, another to the exuberant atomic age / space age “googie” architecture of motels, bowling alleys, and drive-in restaurants. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Oral Roberts University campus from the 1960s echoes the cardboard Buzz Corey spaceport that I assembled on my bedroom floor in 1952.

The ability of the sleek side of twentieth-century design to represent the future has an uncomfortable implication. Embedded is an unspoken assumption that cities aren’t changing all that much or that fast. The last two generations, suggest several observers, have seen few innovations that have fundamentally changed the character of urban areas. Tyler Cowan has called it “the great stagnation,” Peter Thiel has complained about “the end of the future,” and Neal Stephenson about “innovation starvation.”7 Urban areas changed drastically from 1840 to 1940, but perhaps not so much since then. Most adults in the 2010s could be transported back to the 1940s and still get along—at least if their dads had made sure they learned how to drive a stick shift. Elevators no longer need operators for the mind-numbing work of opening doors and calling the floors, but they are still elevators. Traffic lights still cycle back and forth between red and green. I write on a two-year-old laptop, but I charge it with electricity from Columbia River dams and transmission lines that predate World War II. Even implementation of “big data” to create “smart cities” is being applied to old functions like better traffic-light cycles and more efficient siting of firehouses.

Jean-Luc Godard shot the science fiction film Alphaville in the modern buildings of Paris, but the advertising poster placed the main characters in front of a much more futuristic skyline. This is one of the most common designs for science fiction book covers and film advertising, used in movies as different as Metropolis and Logan’s Run. Courtesy Janus Films/Photofest © Janus Films.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment of expectations has involved the impacts of electronic communication. The advent of personal computing and Internet connections in the 1980s spurred great expectations for urban decentralization. Soon, proclaimed the enthusiasts, crowded cities would be obsolete. Production workers would operate machinery by remote control, and professional workers would relocate to their favorite seacoast, mountain valley, or small town. Well, a bit of that has happened: radiologists can read X-ray results at a distance, college students can win big bucks with online poker, and soldiers can operate drones from consoles an ocean and continent away from their West Asian targets. Nevertheless, cities have continued to grow in both developed and developing nations. Superabundant flows of information turn out to favor greater centralization of decision making because on-site managers are less essential. The result has been the solidification of a global urban hierarchy topped by what sociologist Saskia Sassen calls global cities—New York, London, Tokyo, Paris, Hong Kong, and their ilk. Meanwhile, the centers of many old industrial cities like Birmingham (UK) or Chicago look just as good as or better than they did fifty years ago with the benefit of changing generational tastes and massive reinvestment.

SKYSCRAPER CITY

If real cities haven’t lived up to techno-hype, the science fiction fixation on the sleekest of cityscapes to signal the future raises an interesting question about the technological city. The visual choices of film designers suggest, by and large, that the future will be not only shiny but also tall, a place where glass-and-steel towers frame urban airways through which the aircars weave. This is an imaginative leap, for cities over many millennia were far wider than they were high. Limited to five or six stories by construction technologies and the willingness of people to trudge up stairs, they draped over the landscape like slightly lumpy pancakes. Over the last 150 years, cities have been rethought and sometimes rebuilt in ways that prioritize height over breadth. Indeed, the vertical city of the real twenty-first century—Hong Kong, New York, Shanghai, Dubai—is itself a radical reimagining of traditional cities. In turn, science fiction has taken skyscraper districts as the most common jump-off for even bigger, higher, and denser cities of the future. For one example take Bruce Sterling’s description of future Singapore in Islands in the Net (1988): “Nightmarishly vast spires whose bulging foundations covered whole city blocks…. Storey after storey rose silent and dreamlike, buildings so unspeakably huge that they lost all sense of weight; they hung above the earth like Euclidean thunderheads, their summits lost in sheets of steel-gray rain” (215).

The mechanically powered safety elevator, thanks to Mr. Otis, is one of the two great transportation inventions from the century of steam, along with track-and-vehicle combinations like railroads and streetcars. Combined with the development of steel-frame building construction, the elevator gave Paris the Eiffel Tower and New York and Chicago the first skyscrapers, helping to make the towering office building a visual clue and then cliché for visualizing the future.

The change was not instantaneous. It took time for an aesthetic keyed to seeing magnificence and power in great horizontally spread buildings to transform into the admiration of the vertical. In the nineteenth century, architects designed and developers filled new downtowns with “business blocks.” Four- to six-story cubes and oblongs, they were meant to impress with their solidity. The best were magnificent structures like the Pension Office in Washington (now the National Building Museum) and Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building in Chicago, a massive cube with a slender campanile tower that anchored Michigan Avenue. These were buildings that covered and held ground, defining their importance by lateral reach.

The new apartment blocks that housed the bourgeoisie of Vienna and Paris after 1870 were of the same architectural species. Four or five floors high, they extended in solid, never-ending rows along the avenues and boulevards. In the walkup city, the first floor above ground-floor shops was the prime location—the piano nobile for Italian town houses and palazzos, the bel étage in French apartments. Inverting the modern association of height and hierarchy, the top floor was despised for its cold and inconvenience, not valued for nice views, relegated to servants and starving artists.

The evolution of skyscrapers and a skyscraper aesthetic from this very different starting point is a story told time and again. From the 1890s to the 1930s the vertical gradually conquered the horizontal. The Metropolitan Life Building of 1909 was still a solid block with a now more substantial tower. The Woolworth Building, which took away the title of world’s largest building in 1913, shifted the relative importance of base and tower. The big three that followed—the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building, and the RCA Building—drew all their appeal from the vertical. In the nineteenth century, “skyline” had meant the natural horizon of country vistas. Only in the 1890s did writers commonly apply it to the horizon line of downtown buildings (the first such citation in the Oxford English Dictionary comes from George Bernard Shaw in 1896).

The high tower has endured as the symbol of modernity and urban importance. If New York and Chicago had skyscrapers, dozens of smaller cities wanted them too. Nebraska and North Dakota completed high-rise state capitols in the early 1930s. Los Angeles (1928) and Buffalo (1931) built high-rise city halls. Before the Great Depression hit, the Baltimore Trust Building reached thirty-four stories, Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning reached forty, and the American Insurance Union tower in Columbus, Ohio, reached forty-six. “Des Moines is ever going forward,” reported one of its newspapers. “With our new thirteen-story building and the new gilded dome of the Capitol, Des Moines towers above the other cities of the state like a lone cottonwood on the prairie.”

It was an easy step from Des Moines to Zenith, the fictional amalgam of Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and Kansas City where Sinclair Lewis placed thoroughly modern real estate salesman George F. Babbitt in his 1922 novel. As the novel opens and Babbitt has yet to stir in his new Dutch colonial house in the new upscale suburb of Floral Heights, “the towers of Zenith aspired above the morning mist; austere towers of steel and cement and limestone, sturdy as cliffs and delicate as silver rods. They were neither citadels nor churches, but frankly and beautifully office-buildings.” As Babbitt tells the Zenith Real Estate Board, their city is distinguished by “the Second National Tower, the second highest business building in any inland city in the entire country. When I add that we have an unparalleled number of miles of paved streets, bathrooms, vacuum cleaners, and all the other signs of civilization … then I give but a hint of the all round unlimited greatness of Zenith!”

With the aspiring constructions of Des Moines, Cleveland, and Zenith in the background, the last century has seen an imaginative three-way interaction between real buildings that have reached taller and taller, grandiose proposals from the drawing boards of ego-rich architects, and often beautifully rendered cityscapes from the easels of visionary (or hallucinatory) artists.

In the 1920s Le Corbusier—one of most self-confident of the design utopians who shaped twentieth-century ideas about cities—created a series of schemes for high-rise cities: a diorama and drawings for a “City for Three Millions” in 1922, the Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) in 1924, and in 1925 the Voisin Plan for central Paris, which would have carried modernity to a shocking logical extreme. Artists struggled to stay ahead of the curve when technological capacity grew and architects could let their minds out-roam the practical and politics (not even Baron Haussmann could have done that to Paris).

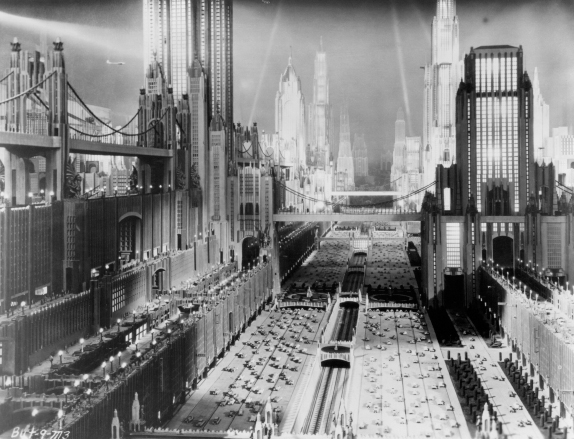

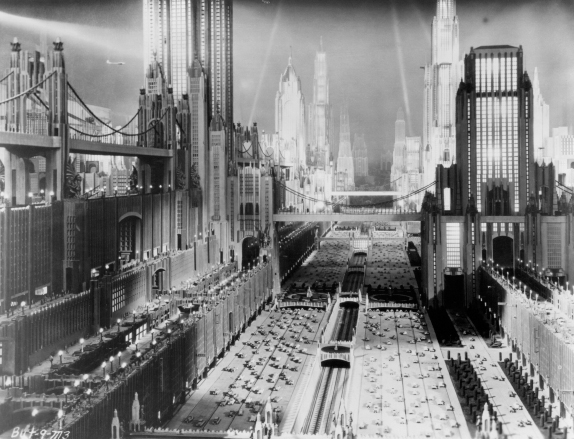

Meticulously constructed and articulated, the miniaturized city used for shooting the background for the 1930 film Just Imagine had a counterpart at the end of the decade at the New York World’s Fair, where General Motors exhibited a scale model of a freeway-and-suburb metropolis of the future. Courtesy Fox/Photofest © Fox.

Artists struggled to stay ahead of the curve. The most prominent in the United States was New Yorker Hugh Ferriss, who staged a “Drawings of the Future City” exhibit in 1925 and followed with drawings for “Titan City,” or New York from 1926 to 2026, exhibited at Wanamaker’s department store. His drawings celebrated technological progress with ziggurat towers and sweeping searchlights illuminating urban canyons. The images can seem dark and foreboding, but General Electric and Goodyear advertisements adopted the same imagery, as did the miniaturized “Gotham” set for Just Imagine.

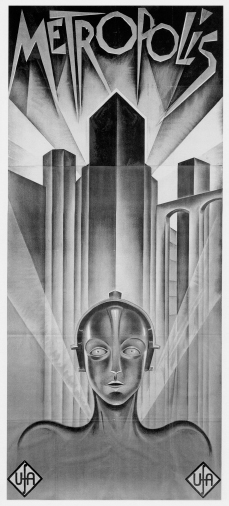

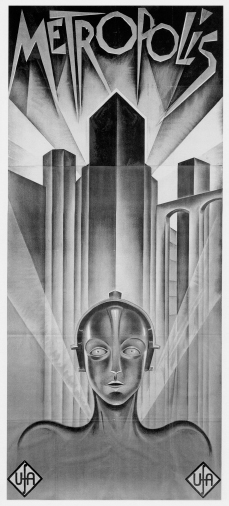

Rockefeller Center is a close steel and stone relative.8 The Ferriss vision was echoed in the sets and backdrops for the silent movie classic Metropolis (1927), inspired by director Fritz Lang’s first visit to New York, and anticipated the style of Batman’s Gotham City.9

The backdrops for Fritz Lang’s seminal film Metropolis reference thirty years of visionary depictions of New York and similar cities. Realistic skyscrapers rise next to fantasy architecture that recalls Pieter Brueghel’s 1563 painting of the Tower of Babel, while traffic speeds across precarious elevated highways and railways and aircraft dodge through the concrete canyons. Courtesy UPA/Photofest © UFA.

Dial forward to 1956, when Frank Lloyd Wright proposed a mile-high skyscraper (“The Illinois”)—four times the height of the Empire State Building. It would have climbed 528 stories, with fifteen thousand parking stalls and 150 helicopter parking slots. A half-century later, the world was catching up to both Wright and Bruce Sterling with stand-alone super-skyscrapers in Taipei, Kuala Lumpur, and most recently Dubai, where the Burj Khalifa soars more than a half mile high. Critic Witold Rybczynski draws direct parallels in engineering and design from “The Illinois” to the Burj Khalifa: use of reinforced concrete, a tapering silhouette, a tripod design, and “a treelike central core that rises the full height of the building to become a spire”—all in all a sort of stalagmite form to bring a touch of fantasy to the common corporate glass-and-metal box.10

This poster for Metropolis stresses the eerie and the fantastic, with the machine-human version of the heroine Maria backed by an abstracted skyline framed by the beams of searchlights. Courtesy UPA/Photofest © UFA.

This poster for the French release of Metropolis highlights the gigantic scale of the emerging megacity, multiplying the sort of step-back skyscrapers that filled Manhattan after the city’s 1916 zoning ordinance. Courtesy UFA/Photofest © UFA.

In the real estate business, hype and high-rise go together: there are the real buildings we have just mentioned, ambitious but serious designs that don’t quite get off the ground, and exuberant entries into design competitions by big names like Paul Rudolph, Paolo Soleri, and Rem Koolhaus that are little more than thought experiments in the style of architectural science fantasy. From there, it’s an easy segue to artistic renditions of future cities. The difference: without needing even a cursory bow to engineering realities and financial possibilities, visual artists can assemble a thousand Burj-Khalifas into a single super-metropolis.

I examined two websites that have assembled future city art: One offers “45 incredible futuristic scifi 3D city illustrations” and the other “100 imaginative cities of the future artworks.”11 By my eyeball categorization, 106 of the images are vertical cities that rise to wild and giddy heights, compared to only 14 low-rise cities that stretch to distance horizons, 9 floating, hanging, or orbiting cities untethered from a planetary surface, and 16 images that combine the horizontal and vertical in ways that most resemble actual twenty-first-century cities with downtowns and suburbs. That is nearly a three-to-one margin for the vertical in the minds of artists of the fantastic—who also prefer the view from above or afar to depictions with a viewpoint in the midst of the urban action.

Future city drawing and paintings of the twenty-first century are strikingly similar to “King’s Dream of New York,” an image included in King’s Views of New York (1908–9). Moses King was a prolific compiler of guidebooks and pictorial portraits of Boston and New York, combining text with hundreds of photographs. New York, the American Cosmopolis: The Foremost City of the World was a typically immodest title from his busy publishing enterprise. In his rendition, Broadway is a concrete canyon, the real Singer Building is dwarfed by higher towers connected by sky bridges, and blimps and dirigibles swarm the sky.12

INSIDE THE TOWERS

The artists highlight the point that is implicit in proposals for unbuilt super-duper skyscrapers: height itself is the techno feat. Whether created by Frank Lloyd Wright or a computer artist, what makes the building or city a speculative fiction is the assumption of building technologies that can scale up the typical individual Chicago skyscraper to something bigger than currently possible. From the building that depends on particular machines for circulating people, air, and water among multiple floors (the real skyscraper of 1890–1920), the science fiction imagination moves to high-rise cities that depend on the sets of machines assembled in currently impractical ways.

British writer Ian Whates invites readers to visit “the city of a hundred rows” in City of Dreams and Nightmares (2010).13 The setting is Thaiburley, a high-rising city of a hundred levels or “rows.” To a traveler from the rural hinterlands, “the towering city walls were just as magnificent and awe-inspiring as imagination had painted them. The closer the city grew, the more its sheer scale became apparent” (176). The elite live at the top in the City Above, and hardscrabble folks dwell at the bottom in the cavernous City Below. Communication is by stairs, by escalators that span segments of a dozen or fifteen levels, and elevators that are paired so one goes up while the other down. These lifts span a limited number of levels, and you have to get off and cross to another platform to get to the next stage (think about riding multiple cog railways and cable cars to reach the summit of the Schilthorn or the Jungfrau in Switzerland). Much of the space of the Rows is interior rooms and dwellings, but each level has terraces that open to the air … you can fall off!

Whates tries to imagine Thaiburley as a fully articulated city. There are food supply levels, Shopping Rows, and a ground-level Market Row that has spread beyond the base of the city. “From Streets Below to the Market Row / From taverns and stalls to the Shopping Halls” goes a nursery rhyme. Further down, beneath the Market Row, are subsurface levels for the poor in “the vast cavern which housed Thaiburley’s lowest level” (56). Here are bazaars, aliens, street gangs, a river that provides power (and carries away waste), docks, factories, and “the Ruins” where there are taverns, whores, workers, bargemen, and beggars. Routes to the City Above are lucrative and claimed by groups and gangs who charge tolls. It is not clear how the basic large-scale supply of the City Above is organized, but there are scavengers called Swarbs (Sanitation Workers and Refuse Burners) who string nets to catch things and people that fall.

Even taller than Thaiburley is Spearpoint, the physical and conceptual pivot for Alastair Reynolds’s Terminal World (2010). It is a towering city in the shape of a cone, with a relatively wide base, a curved taper to higher levels, and then finally a spire that goes beyond habitable levels. Its footprint at the base is fifteen leagues across, narrowing to one-third of a league across at fifty leagues above the ground, whence it keeps rising into the vacuum (86). At this scale, it is big enough to house thirty million people (101).

To complicate the impressive techno feat of enormous height, Reynolds throws in weird physics. In horizontal bands are zones in which different levels of technology are physically possible: from bottom upward are Horsetown, Steamville, Neon Heights, Circuit City, a cyborg zone, and the Celestial Levels (whose “angel” inhabitants have evolved the ability to fly). People live in complexes of buildings on the surface of the tower and partway into the interior. Connections are by mechanical funiculars and by a railroad that runs on a curving ramp that circles and recircles the tower like the Tower of Babel in the images of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Gustave Doré. Horsetown encircles the base and spreads beyond it onto the surrounding planetary surface.

Despite their gargantuan height, Thaiburley and Spearpoint share a family resemblance with Burning Bright and Alphaville. Super-tall city buildings are cool, but height itself is not essential to the plot element of social hierarchy. Reynolds could just as well have imagined a horizontal city of concentric rings with different physical principles, with status declining from center to edge as in preindustrial cities. Whates has a lot more fun with the City Below than with the City Above, telling what is basically a story of cops, street gangs, and young people on the run through back alleys and abandoned buildings. Nor does the inevitable physical complexity of these tower-cities play an important role. Apart from describing the transportation systems, the authors do not take all that much effort to imagine how such cities might actually work as artificial ecologies. There are workshops and shops and apartments inside Spearpoint and Thaiburley, but they are ordinary spaces, and the exciting action takes place on the outsides of the structures as bodies are pitched or fall to their death and characters flee and are chased by air, stairways, and funicular railways that cling to the surface.

Although Spearpoint is an extravagant science implausibility, it was easy for writers in the later twentieth century to draw on the commonly accepted critique of massive public housing projects as alienating environments that nurtured social problems—whether U.S. examples like the infamous Pruitt-Igoe buildings in St. Louis or the sterile working-class apartment blocks of Paris or Moscow—and project social breakdown. Thomas Disch set his grittily detailed novel 334 (1972) in a subsidized twenty-one-story building at 334 East Eleventh Street, New York. In the 2020s its three thousand residents are supervised by a paternalistic bureaucracy, cope with malfunctioning elevators and deteriorating services, scam social workers to survive, and take refuge in drugs, television, and meaningless violence. As science fiction scholar Rob Latham has pointed out, Disch’s near-future New York embodies much of the analysis of neo-Marxist geographers like David Harvey and Manuel Castells. Except for the elderly isolated in upper floors, residents are free to use the city around them, but only on the terms set by the structures of power and authority.14

Robert Silverberg and J. G. Ballard, in contrast, set novels entirely within high-rise buildings and use those settings to explore the impacts of concentrated and claustrophobic living on individuals trapped inside and unable to escape to freedom or adventure. Silverberg’s The World Inside (1971) is pure science fiction, positing a world in which seventy-five billion humans live in megabuilding “urban monads”—urbmons—that could be characterized as cheerful dystopias. Ballard sets High-Rise (1975) in a skewed present in which an expensive condominium tower in the London Docklands erodes all social bonds and turns its residents into murderous sociopaths. In both books, however, the tall building is both a technological accomplishment and something more, a presence that conditions and drives individual behavior as much as the Alaska wilderness changes Buck from domestic pet to feral creature in Call of the Wild.

Silverberg wrote the linked stories that constitute The World Inside in 1970 and 1971, at a time when both the public and science fiction were obsessed with the threat of overpopulation. In good SF fashion, Silverberg decided to reverse the expectations and explore the possibilities of a society in which population growth was applauded—requiring vast buildings to house the multitudes and, in turn, elaborate systems of social regulation to maintain order. The social reversal draws directly on the sexual revolution of the baby boomer generation: urbmon society encourages sex for procreation from the early teens, has no nudity taboo, and promotes open promiscuity, with every woman theoretically available to any man. The structures that house the busy billions similarly extrapolate then-current urban thought. They are grouped in clusters with names like Chipitts, Sansan, and Wienbud (in Europe)—terms coined following publication in 1961 of Jean Gottmann’s Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States, which described the Boston-Washington corridor as an emerging urban superregion. Silverberg began thinking about the structures themselves by projecting familiar New York skyscrapers, but he soon found Paolo Soleri’s fantastic schemes for grotesquely gigantic self-contained arcologies that would concentrate human beings and free up the natural landscape (Soleri’s Arcology: The City in the Image of Man is one of the most misnamed books ever).

Urban monads are indeed arcologies. An urbmon tapers upward from a relatively wide base to allow space for factories and supporting machinery on the lower levels. Each towers an identical one thousand floors high, divided into forty-floor cities that take their names arbitrarily from historic cities. In Urbmon 116 of the Chipitts cluster, where the stories take place, Reykjavik is on the bottom and Louisville is on the top. The original intent was fifty families per floor, but the population growth that the society so vigorously encourages means that most floors have more like 120 families, each crammed into an apartment that has been reduced to a single room. A relatively successful academic on a high floor has ninety square meters for six people, who use efficiently designed inflatable, wall-mounted, and built-in furnishings and appliances. The result is roughly eight hundred people per floor, thirty-two thousand per city, and eight hundred thousand per building. When Urbmon 116 reaches close to nine hundred thousand, it is time to hive off excess people to join with the extras from other towers to populate a brand-new urbmon.

Urbmonites never go outside, and many never stray beyond their own city except on school field trips. One character looks down at the manicured surroundings: “Below her are the tapered structures that hold the 40,000,000+ people of this urban cluster. She is awed by the neatness of the constellation, the geometric placement of the buildings to form a series of hexagons within the larger area. Green plazas separate the buildings. No one enters the plazas, ever, but their well-manicured lawns are a delight to behold from the windows of the urbmon” (49). Beyond the lawns, 90 percent of the continent is devoted to agriculture, with strangely primitive villagers operating vast industrial farms in exchange for manufactured goods from the cities—much like Soleri’s scheme to free the landscape of nasty human beings.

This is a world of literal social climbing. The cities are stacked by status, from administrators on the top floors to maintenance workers at the bottom. Nightwalking is the socially sanctioned practice of males finding casual sex partners by prowling corridors and entering random apartments. To nightwalk in higher cities is to aspire; to nightwalk in lower cities is to go slumming. Sociocomputator Charles Mattern explains to a visitor from Venus that they try to encourage contact between cities. “Sports, exchange students, regular mixed evenings. Within reason, that is. We don’t have people from the working-class levels mixing with those from the academic levels, much. It would make everyone unhappy, eh?” (29). Another character moves through Urbmon 116 as the liftshaft carries her upward in her imagination. “Up through Reykjavik where the maintenance people live, up through brawling Prague where everyone has ten babies, up through Rome, Boston, Edinburgh, Chicago, Shanghai, even Louisville where the administrators dwell in unimaginable luxury” (49).

Silverberg uses the massive physical presence of the urbmon as both the cause and the representation of inexorable social inertia. Several of the component stories deal with misfits whose vague dissatisfaction leads them to challenge the system. One commits suicide, and other “flippos” are summarily disposed of—arrested and immediately tossed down a recycling chute. Others find ways to reconcile themselves to their lives. Even the discontented understand and appreciate the vast inter-connectedness of urbmon society. One misfit realizes, when describing Urbmon 116, that it is “a poem of human relationships, a miracle of civilized harmony” (207). A drug-tripping musician envisions the intricate connections: “For the first time he understands the nature of the delicate organism that is society; he sees the checks and balances, the quiet conspiracies of compromise that paste it together. And it is wondrously beautiful. Tuning this vast city of many cities is just like tuning the cosmos group [a musical combo]: everything must relate, everything must belong to everything else” (90).

The result, even as world population continues to rise from seventy-five billion toward ninety billion, is equilibrium. The final paragraph takes an irenic tone: “Now the morning sun is high enough to touch the uppermost fifty stories of Urban Monad 116. Soon the building’s entire eastern face will glitter like the bosom of the sea at daybreak. Thousands of windows, activated by the dawn’s early photons, deopaque. Sleepers stir. Life goes on. God bless! Here begins another happy day” (256). This ending repeats much of the book’s opening paragraph, which starts: “Here begins a happy day in 2381” (15). We have come full circle to reaffirmation and stability.

If Silverberg’s urbmons are vast machines for maintaining social equilibrium and keeping people happy, not so the building in J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise, where stasis has no chance against chaos. Pity the ambitious and luckless Britons who have bought apartments in the brand-new tower within sight of the City of London. Set in the present of the 1970s, this is a book that has to work its way into the science fiction realm, and succeeds with devastating results. Things start a bit tense in the new building because of buried tensions between middle-class people on the lower floors and higher-status residents at the top. Upper levels have dogs, lower levels have children. Top-floor residents treat children as an intrusion and exclude them from an upper play area and pool to which they are supposed to have access. Everyone understands that there is a rough upper/middle/lower division (66–67).

The building itself is tiny compared with urbmons or Spearpoint, with two thousand residents in one thousand apartments in a forty-story high-rise. Nevertheless, it sucks people into its vortex. The building is largely self-contained; the entire tenth floor is a retail concourse with supermarket, liquor store, hair salon, bank, school, pools and other recreation areas. In the beginning (the story starts after the building is occupied), residents commute to work, pick up their mail, and watch news on the telly. Quickly, however, the outside world loses its salience. Men cease to leave the building for their jobs. Moms keep kids home from school, hunkering in shuttered apartments. Even the strongest personalities find that they can’t leave, even when they claim that is what they want. The police and other public authorities oddly ignore the building even as its parking lot fills with smashed and abandoned cars.

Tensions breed chaos over three short months. Trouble starts with a lot of noisy partying, as if all the residents are having simultaneous midlife crises. Small incidents soon escalate into random violence. The water supply fails; electricity goes out floor by floor; garbage piles up. Management ceases to respond to complaints. Residents of adjacent floors cluster into clans for self-defense and battle in the interior corridors with makeshift weapons. Each floor tries to block adjacent stairwells and guard elevator lobbies. Soon the clans fragment into small clusters of apartments. “The clan system, which had once given a measure of security to the residents, had now largely broken down, individual groups drifting into apathy or paranoia. Everywhere people were retreating into their apartments, even into one room, and barricading themselves away.” There are groups of wilding women, probably cannibalism, and finally everyone for him or herself. The last three survivors can look across the abandoned parking lot to see the same process starting in a newer tower.

High-Rise is barbed satire that skewers Britain on the verge of the Margaret Thatcher years, when the gospel of free markets impoverished the public sphere, and when the Docklands district would go through cycles of real estate boom and bust—although not as disastrously as the High-Rise high-rise. Ballard offers a dubious psychological explanation for the breakdown (the building is like a mother that allows residents to turn into uncontrolled two-year-olds). A better analogy is to see the building as a version of the generation starship (see chapter 4). Indeed, Ballard describes it both as a spaceship and as “a small vertical city, its two thousand inhabitants boxed up into the sky” (15). There are strong parallels to the generation ship in Brian Aldiss’s Non-Stop (1958), where the command deck (building management) has ceased to function and society has devolved to tribal warfare within confined spaces. What is different is the external resolution and rescue that Aldiss provides. Ballard has no such hope, giving us, perhaps, Non-Stop meets Lord of the Flies.

Skyscrapers are particularly tempting techno feats that still fascinate after 120 years. Exciting visions of towering supercities from the early twentieth century influenced not only the golden age science fiction writers of the 1930s and 1940s but also the boomer generation who grew up with those stories as part of their SF universe. Some readers and writers have since repudiated it, but others have recapitulated or incorporated it into new work. The choices that designer Syd Mead made for Blade Runner very explicitly invert the techno-utopianism of Hugh Ferriss. William Gibson’s early story “The Gernsback Continuum” from 1981 is both homage and critique of the visions of golden age science fiction. Its gentle satire posits an alternative history in which the world of the pulp covers breaks through into “reality,” providing fleeting visions of cars like an “aluminum avocado with a central shark-fin rudder jutting up from its spine” and a city that mirrors that in Metropolis: “Spire after spire in gleaming ziggurat steps that climbed to a central golden temple tower ringed with the crazy radiator flanges of the Mongo gas stations…. Roads of crystal soared between the spires…. The air was thick with ships: giant wing-liners, little darting silver things … mile long blimps, hovering dragonfly things that were gyrocopters” (8–9). Gary Westfahl comments that the story “pays fond tribute to the now-quaint prophecies of science fiction writers and futurists of the 1920s and 1930s, and ponders how their visions still influence residents of the future they failed to predict.”15

The exaggeration of these already larger-than-life buildings can authenticate otherness, as in thousands of drawings and paintings of future cities, but it can also call the whole idea of a bright urban future into question. In The Futurological Congress (1971; translated 1974) the brilliant Polish writer Stanislaw Lem sends his recurring character Ijon Tichy to a scientific meeting held at the Costa Rica Hilton, which rears 164 stories into the sky and offers bomb-free rooms and the luxury of an “all-girl orchestra [that] played Bach while performing a cleverly choreographed striptease.” At the meeting, convened to address seven world crises (urban, ecology, air pollution, energy, food, military, political), a Japanese delegate presents plans for the housing of the future: “eight hundred levels with maternity wards, nurseries, schools, shops, museums, zoos, theaters, skating rinks and crematoriums … intoxication chambers as well as sobering tanks, special gymnasiums for group sex (an indication of the progressive attitude of the architects), and catacombs for nonconformist subculture communities” (21). Seventeen cubic kilometers in volume, the completely self-contained building would reach from the ocean bed to the stratosphere. A scale model was already at work recycling all its waste products into food. The outcome of techno city may not be techno utopia, says Lem; it may be artificial bananas, ersatz wine, and synthetic cocktail sausages.