The Learned Men and the Secretary

“She herself was so used to the water when she first came to France, she could not live without it, and was used to diving in overhead and ears, and to continue swimming and diving like an otter, or some other amphibious animal. And when they restrained her from this practice, when she was a little tamed and civilized, she thought her health suffered for want of it.”

-from the preface to the English translation of Mme. Hecquet’s Histoire d’une Jeune Fille Sauvage by James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, published in Edinburgh in 1768

Throughout history many human societies have indulged in the practice of swimming, but eighteenth-century France was most definitely not one of them. Plunging into a lake or river stripped down to light underclothing or even – gasp! – completely naked was simply not done. Why would a person want to do such a thing, except, occasionally, to wash off the residue of hard physical labour?

A brief dip for bathing purposes certainly wasn’t what drove Memmie LeBlanc into the water. To all accounts she was a vigorous swimmer, who exulted being in water, as the above quote attests. For the Wild Girl, swimming was the most natural thing in the world. Which meant, of course, that the habit had to be bred out of her – along with the eating of raw meat and climbing trees – and her keepers proceeded to do just that.

Over the past decade I’ve pondered the roots of my deep sense of kinship with Marie-Angelique, but our shared love of swimming was the jumping-off point. (Her propensity for climbing trees, not so much). I’m a swimmer, too. I need to be in water on a regular basis, and not in a pool (though sometimes that’s the only option) but a natural body of water. For years I’ve been swimming daily in Lake Ontario, near where I live on Toronto Island, for as much of the year as I can. For me, water is a physiological and psychology necessity. It keeps me sane. Reading accounts of the tactics used to keep Marie-Angelique out of the water filled me with dread. Barring her from swimming felt to me like a form of torture.

In her own day, the Wild Girl’s penchant for the water was one of the main factors in the sensational curiosity she aroused among the general public. But there was a smaller cohort of distinguished intellectuals, “Learned Gentlemen,” who attempted to rescue her story from the realm of myth and fairy tale and situate it in a rational, understandable context. Back in the eighteenth century, there weren’t practising “scientists” in the way we think of them now. In fact, though the present-day practitioners of hard science are somewhat loath to admit it, the roots of modern science lie in the discipline of philosophy – more specifically, what was known as “natural philosophy.” The pioneers of physics and astronomy, Newton and Galileo, both answered to the title of “natural philosopher” in their own time. (The title of Newton’s magnum opus was Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy.) And while, like modern scientists, most natural philosophers believed in the primacy of empirical evidence, they didn’t have access to the modern system of controlled experiments, which was in its infancy. The boundaries between the various disciplines were more fluid than they are today, freeing these learned men, supported by patrons or their own personal wealth, to follow wherever their eclectic interests led.

Few eighteenth-century figures had greater renown than Charles Marie de la Condamine, the first of the learned gentlemen to investigate the mysterious case of the Wild Girl. In fact, La Condamine was as much an explorer and adventurer as a natural philosopher. He was most famous for his trips to South America, where he spent ten years measuring degrees of latitude and longitude around the equator, led the first scientific exploration of the Amazon, and discovered the use of quinine, an extract of cinchona bark, to cure malaria. He first met Marie-Angelique about ten years after she appeared in Songy. By then she had learned to speak, and only traces of her life in the wild persisted. When he first heard about the Wild Girl, he was skeptical and decided to find out the truth for himself. Through several meetings over the next decade, he concluded that the basic outlines of her story were true. La Condamine was determined to bring a degree of rigour to the investigation, to put an end to the idle speculation: Was she Norwegian? Caribbean? Did she come from a tribe of cannibals? Curiously, he turned over the heavy lifting of this investigative task to a little-known person with no standing in the circle of natural philosophers. And a woman to boot.

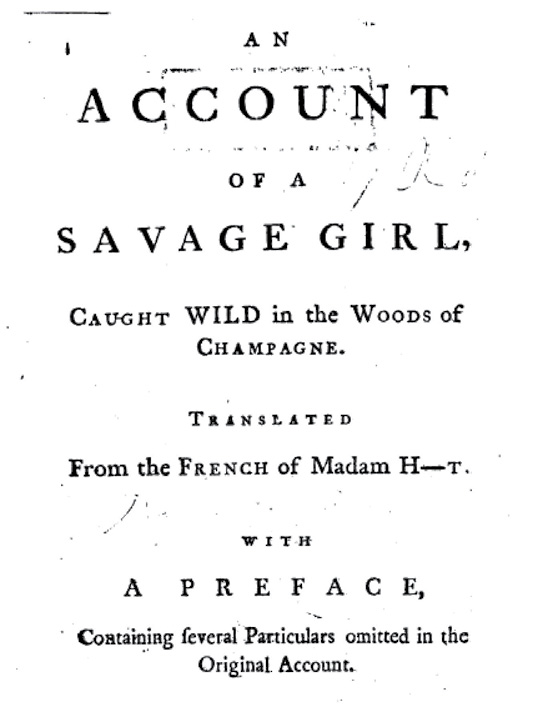

Marie-Catherine Homassel Hecquet is one of those people whom history remembers only for her association with someone far more interesting. Her biography of Marie-Angelique LeBlanc, Histoire d’une Jeune Fille Sauvage Trouvée dans les Bois a l’age de Dix Ans, published in 1755, was for many years regarded as the definitive account of the Wild Girl’s life. And yet Hecquet’s contribution to unravelling the mystery of the Wild Girl has been minimized; her role reduced to something like a glorified secretary to La Condamine. Hecquet herself did little to counter this impression. As she wrote in her preface, “This narrative has been drawn up under the immediate inspection of M. de la Condamine, whose curiosity and accuracy in matters of this sort is well known.” Even now, speculation persists that Hecquet simply provided a pseudonym for the true author, who was La Condamine himself. Aside from being an example of garden-variety eighteenth-century sexism, it may have had more to do with the fact that the Histoire was Hecquet’s first book, and the only one published in her lifetime. The imprimatur of someone with La Condamine’s status was no doubt crucial to the work being taken seriously.

Whoever conducted the interviews or did the actual writing, the Histoire d’un Jeune Fille Sauvage is an impressive piece of work. The range of questions Hecquet posed and her attention to detail go a long way toward making order of the strange saga. She is careful not to gloss over areas of uncertainty and cautions that in some cases Marie-Angelique might be conflating her own memories with details suggested to her by others. Overall, Hecquet succeeds in constructing a plausible narrative, by modern standards as well as those of her own time. The first pages of the book are drawn from the early eyewitness accounts and recount the much-told tales – the killing of the dog, the grabbing and eating of the raw chicken. The book states that early observers were “of the opinion that she was about nine years of age,” which, as we’ll see, is a detail that became the source of some controversy. The book also documents the Wild Girl’s many attempts to escape in the early days after she was discovered. In one, she is found asleep in a tree, on a bitterly cold night, which gives rise to the legend of her extraordinary tolerance for cold temperatures.

From the hearsay of third-person testimony, Hecquet moves on to the findings of her own interviews, in which Marie-Angelique details her vague recollections of her early life, her travels with an unnamed companion, and a harrowing account of being fired upon by a hunter while swimming across the Marne. Trees, Marie-Angelique tells Hecquet, were their refuge from predators, cradling them to sleep at nighttime and providing watchtowers to survey their surroundings from a distance. Before she acquired language, whenever Marie-Angelique was asked about her mother or father, she would point to a tree.

Here is found one of the most striking elements of the Wild Girl’s story; an account of her fierce brawl with her unnamed companion arguming over a chapelet – a rosary they found on the ground. This event is one of the first incidents Marie-Angelique told Hecquet about, recounting in great detail how she struck the other girl on the head, causing a bleeding wound which she quickly tried to stanch with the skin of a frog. “After this,” Hecquet notes with understatement, “they separated.”

Here, as elsewhere in the book, Hecquet cautions that Marie-Angelique’s recollections may not be completely reliable, due to the passage of time and the fact that she was only able to describe events after she’d learned to express herself in French. But one thing about which Hecquet expresses no doubt is Marie-Angelique’s horror of being touched by men. The book recounts a number of incidents in which she shrieks at men who approach too closely, in particular one whose face she slaps with a piece of raw meat, nearly knocking him off his feet. Hecquet speculates this fear might stem from a “dread of ill usage” Marie-Angelique had experienced sometime in the past – a euphemism for what we now call sexual assault.

There is much discussion of Marie-Angelique’s health problems, which both she and Hecquet attribute to the forced “taming” and change of diet to which she was subjected. Marie-Angelique tells Hecquet that in one of her convent stays, the nuns refused to let her outside because she wasn’t sufficiently cured of her desire to swim and climb trees. In fact, these two activities proved to be the most difficult of her wild habits to shed, which should have been no surprise. For all that her European overlords considered swimming and climbing trees “unseemly in a girl,” these activities clearly had been a normal – and enjoyable – part of her previous life.

At their very first meeting, Hecquet notes that Marie-Angelique appears to be in delicate health, and also learns that her financial future is uncertain, due to the death of her long-time patron, the Duc d’Orleans. Hecquet expresses great concern for Marie-Angelique’s future well-being, but Marie-Angelique assures her that Divine Providence protected her during her time in the forest and will continue to shield her from harm. Hecquet, a person of devout, even austere piety, is deeply moved by Marie-Angelique’s words, taking them as proof that the savage has truly adopted Christianity.

Hecquet continually probes, without much luck, into Marie-Angelique’s recollections of her early life. But one memory she summons up turns out to be pivotal: Marie-Angelique tells of an encounter she once had, while swimming, with a “huge animal swimming with two feet, like a dog,” with “large, sparkling eyes” and short black hair. Hecquet is certain that the creature is a seal and seizes on this to support her argument that Marie-Angelique “is of the Esquimaux nation2, which inhabits the country of Labrador, lying to the north of Canada.” Other details bolster her thesis, such as Marie-Angelique’s taste for raw fish and her propensity for diving into cold water. Despite Hecquet’s demurrals elsewhere in the book that, given the passage of time, the Wild Girl’s memories are “very little to be depended on,” the vividness of the seal-image convinces her of the Wild Girl’s northern origins.

Hecquet had gleaned a good deal of her knowledge of life in North America from her childhood friend Marie-Andre Regnard Duplessis de Saint-Helene, a nun who emigrated to New France and became Mother Superior at the Hotel-Dieu in Quebec. Though few of Hecquet’s letters have been preserved, Duplessis’ side of the correspondence contains detailed descriptions of the manners and customs of various native groups. The clincher, for Hecquet at least, was Marie-Angelique’s reaction to a collection of Indigenous dolls sent to her by Duplessis. Upon seeing them, Marie-Angelique immediately gravitated to the two figures – a male and a female – in Inuit dress. She told Hecquet they looked familiar, that she was sure she had seen people like them before.

Duplessis’ letters certainly suggest that she had more than a passing knowledge of Inuit life, and she gets many details right, such as their practice of eating raw seal and sewing sealskins for garments. Yet Hecquet chooses to quote this excerpt from Duplessis’ letter of October 30, 1751: “The Esquimaux are the most savage of savages. Though the manner of the other indigenous nations appears extraordinary, they still retain some tincture of humanity. But among the Esquimaux, an almost incredible barbarism universally prevails. They are a nation of Anthropophagi, who devour men whenever they can get them.”

Convinced of Marie-Angelique’s Esquimaux origins, Hecquet proceeds to cobble together a narrative of how the girl might have been brought to Europe, how her ship landed in the Netherlands, and how she and her unnamed companion spent months – perhaps years – making their way through the Ardennes Forest to the Champagne district. She ends the book with several appendices, which include Marie-Angelique’s baptismal record of June 16, 1732 and extracts of letters written by witnesses a couple of months after her appearance in Songy. One of the letters states that Marie-Angelique appeared to be about eighteen years old, which Hecquet dismisses as an error. The same letter refers to the Wild Girl’s “lively blue eyes” – the sole mention of her eye colour in any of the surviving accounts, and a curious detail in light of the belief that she was an indigenous North American.

The Lawyer-Linguist and the Forbidden Experiment

If Hecquet was overshadowed by La Condamine, the one who really stole her thunder was James Burnett, Lord Monboddo. Like Hecquet, Burnett was introduced to Marie-Angelique by La Condamine and met with her a full decade after the publication of Hecquet’s Histoire. Burnett was a prominent Scottish lawyer, and a high point of his legal career was his role in the Douglas Cause, a scandalous inheritance dispute involving false identities and a French rope dancer that gripped Europe in the 1760s. But today he’s most remembered for his connection to the poet Robert Burns. Smitten with Burnett’s daughter Elizabeth, Burns was a frequent houseguest at Monboddo Castle, the family manor near Aberdeen, which still stands today. The poet praised Elizabeth’s beauty in several poems and letters and wrote a famous Elegy upon her untimely death at the age of twenty-four.

Like many learned gentlemen of the eighteenth-century, Burnett’s true interests lay less in his day job and more in natural philosophy, and the new ripples of thought it generated in the European world-view. He took part in the intellectual circles in Edinburgh during the period historians refer to as the Scottish Enlightenment. Burnett carved out a territory for himself in the study of languages and was an early pioneer in the field of linguistics. His magnum opus, entitled On the Origin and Progress of Language, was published in 1774. He was intrigued by accounts of the Wild Girl and seized upon an opportunity to meet her on a Douglas Cause-related trip to Paris in 1765. With his clerk, William Robertson, serving as translator, Burnett conducted a number of interviews with Marie-Angelique. When he returned to Scotland, he had Robertson translate the Histoire, adding a preface that he wrote himself, and he published the English edition in 1778. In the book, Burnett acknowledges his debt to La Condamine and refers to himself in the third person as a “Scotch gentleman of distinction.”

When someone writes a preface to a book it’s usually to praise it, but Burnett didn’t follow the etiquette on that point. In fact, he wasted no time getting around to his main agenda, which was to challenge Hecquet’s view that Marie-Angelique was Esquimaux. His argument relied on his own area of expertise, linguistics, but he also drew on the findings of his own interviews with Marie-Angelique, which expand upon and in some cases – in his words – “correct” statements in the Histoire. His preface mentions only in passing the “hot country” stopover that Marie-Angelique’s ship was supposed to have made before sailing to Europe. His greater interest is in the “cold country” from which she came, for on that point he is in agreement with Hecquet. He believed Marie-Angelique indeed came from a northern country, but he is certain that she herself is not of the Esquimaux nation. His first line of argument is based on her appearance; she has fair skin and smooth features, unlike the Esquimaux who are, “by the accounts of all travellers the ugliest of men, of the harshest and most disagreeable features.” (Sounds like he got his information from the same people as Mme. Duplessis.) There’s a certain poignance when he talks about the forbidden activities Marie-Angelique found it so hard to give up: In her home country, “the children are accustomed to the water from the moment of birth, and they learn to swim as soon as to walk… They are also taught very early to climb trees; a child of a year old there is able to climb a tree.”

Burnett’s ace in the hole was his familiarity with North American Indigenous languages. Having established that Marie-Angelique came from what is now Northern Quebec, on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay, he determines that her people were speakers of the Huron language. From explorers’ reports, Burnett had gleaned that Huron speakers had difficulty forming labial consonants, and made many “guttural consonants, with very little use of the tongue and none at all of the lips.” These characteristics match up with Marie-Angelique’s own memories and his observations of her speech patterns. Burnett says that the use of Huron was “very widespread over all the continent of North America.” In fact, like the broader Iroquoian language family of which it is considered a subgroup, Huron was spoken in the Great Lakes region, but probably did not extend as far north as Hudson Bay. So, though Burnett’s argument may have been a bit of a stretch, given the state of knowledge and eighteenth-century mapmaking, it’s not surprising.

Burnett and Hecquet were asking the same three key questions about Marie-Angelique: Who was she? Where did she come from? How did she end up in the woods in France? They may have arrived at different conclusions, but they both appear to have succumbed to what we now call confirmation bias. Like many who encountered the Wild Girl, Hecquet decided early on that Marie-Angelique was Esquimaux and built her case around that. Given that many of her queries were likely what we would consider “leading questions,” it’s hard not to conclude that Hecquet overplayed her hand. Burnett, who was ostensibly of a more rigorous, empirical bent, nevertheless bent his observations to fit his own linguistic bias.

Burnett had an even broader agenda in studying the Wild Girl. More than a decade after his interviews with Marie-Angelique, he met and studied another, even more famous savage child; Peter the Wild Boy of Hanover, found in the forest in northern Germany in 1725. In his later writings Burnett hypothesized that feral children like Marie-Angelique and Peter might provide science with a glimpse of humankind’s original nature; our primitive state before we acquired language. This quest had a long history that predated Burnett and his eighteenth-century colleagues. The most notorious was the attempt by the Emperor Frederick II, in the year 1211, to discover what he called “the natural language of God” – the language that the Deity would, presumably, have imparted unto Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Frederick ordered that a group of newborn babies be taken from their mothers and raised by nurses in an atmosphere of complete silence. The nurses were allowed to feed, bathe, and clothe the children, but forbidden to prattle or communicate with them in any way. The outcome of this experiment was disastrous. None of the babies survived past childhood, and all perished without ever uttering a single word.

The emperor’s bizarre venture came to be known as the Forbidden Experiment, and it had come to be considered completely unethical well before Burnett’s time. But the desire to observe humans in this “state of nature” persisted and explains much of the abiding fascination for feral children among eighteenth-century thinkers. Here were humans who, having been isolated from human contact from their earliest days, offered an opportunity to observe nature in itself, freed from civilizing influences. Unlike the babies in Frederick’s Forbidden Experiment, the situation of feral children had been brought about by happenstance, and so didn’t pose the same moral dilemma. (Some of these ethical questions are explored in the fascinating 2018 documentary Three Identical Strangers, about triplet infant boys raised apart in a chilling, modern-day version of the Forbidden Experiment.)

Burnett’s studies of feral children were part of his lifelong quest to “trace the progress of our species through all its various stages, to mark by what degrees we have passed from the animal to the savage, and from the savage to the civilized man.” In this he is considered to be a proto-Darwinist, an early proponent of the notion of evolution. Burnett was one of a number of eighteenth-century natural philosophers who toyed with the idea of evolution, including Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. (Charles Darwin’s breakthrough was not the theory of evolution per se but the discovery of how it worked, via Natural Selection.) Like many pioneers, Burnett made mistakes, some of which turned out to be howlers. He was mocked mercilessly by contemporaries for his theory that humans had once had tails, and Samuel Johnson ridiculed his idea that orangutans could be taught to speak. The decline of his late-life reputation provided a bit of poetic justice for Hecquet, who is still dismissed by modern-day commentators for her lack of credentials. In the final analysis, both Burnett and Hecquet did the best they could with what they had to work with, and it’s fascinating that both of them turned out to be partly right about Marie-Angelique’s origins. But it would take another three centuries for the full story to emerge.

2 Because discussion of her nationality appears so frequently in both French and English sources, in this book I use the French version of the now-discredited term “Eskimo.”