Labor and

Delivery

What’s Going On with Your Partner

The entire labor process typically lasts twelve to twenty hours—toward the high end for first babies and the low end for subsequent ones—but there are no hard and fast rules. Labor is generally divided into three stages. The first stage consists of three phases.

STAGE 1

PHASE 1 (EARLY or LATENT LABOR) is the longest part of labor, lasting anywhere from a few hours to a few days (but the average is about eight hours). Fortunately, you’ll be at home for most of it. At the beginning of this phase, your partner may not even be able to feel the contractions. Even if she can, she’ll probably tell you that they’re fairly manageable. Contractions will generally last thirty to sixty seconds and come as much as twenty minutes apart. Over the next few hours they’ll gradually get longer (sixty to ninety seconds), stronger, and closer together (perhaps as little as five minutes apart).

Every woman will have a slightly different early labor experience. My wife, for example, had from six to twelve hours of fairly long, fairly regular (three to five minutes apart) contractions almost every day for a week before our second daughter was born. Your partner may have “bloody show” (a blood-tinged vaginal discharge), backaches, and diarrhea.

PHASE 2 (ACTIVE LABOR) is generally shorter—three to five hours— but far more intense than the first phase. It’s likely to last as much as ten minutes longer if you’re having a boy than if you’re having a girl. If you aren’t already there, it’s time to head off to the hospital. In the early part of this phase, your partner will still be able to talk through the contractions. They’ll keep getting closer together (two to three minutes apart), longer, and stronger. As this stage progresses she’ll start feeling some real pain. The bloody show will increase and get redder, and your partner will become less and less chatty as she begins to focus on the contractions.

PHASE 3 (TRANSITION) usually lasts one or two hours. And once it starts, you can stop wondering why they call it “labor.” Your partner’s contractions may be almost relentless, lasting as long as ninety seconds. And with just two or three minutes from the beginning of one until the beginning of the next one, there’s barely any time to recover in between. The pain is intense, and if your partner is going to ask for some drugs, this is probably when she’ll do it. She’s tired, sweating, her muscles may be so exhausted that they’re trembling, and she may be vomiting.

STAGE 2 (PUSHING AND BIRTH)

This is by far the most intense part of the process—and fortunately for your partner, it lasts only about two hours (“only” being a term that’s used by anyone who’s not in labor. Your partner would probably prefer “for-friggin-ever”). Your partner’s contractions are still long (more than sixty seconds) but are further apart. The difference is that during the contractions, she’ll be overcome with a desire to push—similar to the feeling of having to make a bowel movement. She may feel some unpleasant pressure and stinging as the baby’s head “crowns” (starts coming through the vagina), but this will be followed by a huge sense of relief when the baby finally pops out.

STAGE 3 (AFTER THE BIRTH)

Less than twenty minutes after the baby is born, the placenta will separate from the wall of the uterus. Your partner will continue to have contractions as her uterus tries to eject the placenta and stop the bleeding. See “The Placenta” on pages 249–51 for more.

What’s Going On with You

Starting labor is no picnic, for her or for you. She, of course, is experiencing— or soon will be—a lot of physical pain. You, in the meantime, are very likely to feel a heavy dose of psychological pain.

I couldn’t possibly count the number of times—only in my dreams, thankfully—I’ve heroically defended my home and family from armies of murderers and thieves. But even when I’m awake, I know I wouldn’t hesitate before diving in front of a speeding car if it meant being able to save my wife or my children. And I know I would submit to the most painful ordeal to keep any one of them from suffering. This instinct perhaps explains the adrenaline rush you’ll probably feel. A team of Scandinavian researchers took fathers’ pulses during the birth of their children and found that they went from an average of 72 beats / minute to 115 beats/minute just before the birth. But helping your partner through labor is not the same as deciding to rescue a child from a burning building.

The most important thing to remember about this final stage of pregnancy is that the pain—yours and hers—is finite. After a while it ends, and you get to hold your new baby. Ironically, however, her pain will probably end sooner than yours. She’ll be sore for a few weeks or so, but by the time the baby is six months old, your partner will hardly remember it. If women could remember the pain, I can’t imagine that any of them would have more than one child. But for six months, a year, even two years after our first daughter was born, my wife’s pain remained fresh in my mind. And when we began planning our second pregnancy, the thought of her having to go through even a remotely similar experience frightened me.

Checking Things Out When You’re Checking In

Here’s what Sarah McMoyler recommends to her students. “On the day you check into the hospital, take a few minutes to survey the room and the labor and delivery unit. You’re going to be in that room for hours and hours, go ahead and open up the cabinets to see where they keep the washcloths, gowns, bath blankets, extra pillows. While you’re at it, try to find out where the wheeled stool is (for you to sit on), the shower, the nurse call button, and the controls for the electronic bed. Most of the time the nurse will get these for you, but if she’s also busy caring for other patients, understand that she may not be able to get them as quickly as you need them.”

While you’re getting the lay of the land, be sure to locate the ice chip maker, the snack bar, and the place where they keep those warmed-up blankets. And make a special point of introducing yourself to the nursing staff. Let them know about any special concerns your partner might have. Does she have any allergies? Did she have a bad pregnancy experience sometime in the past? Is she afraid of needles? And tell them about your goals—in particular, your desire to be as involved as possible—while also letting them know that you’d love their input and advice. This is a great time to ask questions. They really are on your side, and they know a ton about labor and delivery. The warmer your relationship with the medical team, the smoother the whole experience will go.

Staying Involved

Being There—Mentally and Physically

Despite your fears and worries, this is one time when your partner’s needs— and they aren’t all physical—come first. But before we get into how you can best help her through labor and delivery, it’s important to get a firm idea of how to tell when she’s actually gone into labor, and what stage she’s in once she’s there.

Helping Her Cope

Throughout labor and delivery, your focus should be on your partner. But because childbirth is such a female-intensive thing, a lot of guys don’t really understand how important they are to the process. The reality is that you’re absolutely indispensible. Yes, there are doctors and nurses and midwives running around all over the place, but your partner is really counting on you most of all to help get her through this. Your being there—and being actively involved—can make a big, big difference. Women whose partners are supportive during labor and delivery tend to have shorter labors and report experiencing less pain. They also have a more positive attitude toward motherhood.

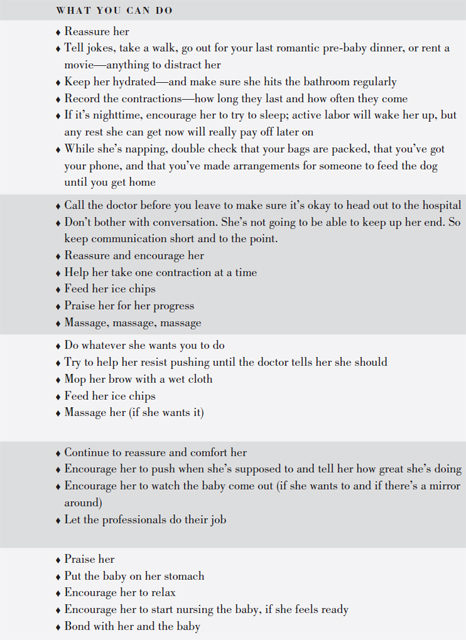

Here are a number of ways you can help your partner cope throughout the labor and delivery. Some of these are drawn from The Best Birth, which I wrote with a wonderful childbirth educator named Sarah McMoyler (a bit more about Sarah’s approach—called the McMoyler method—can be found on page 184).

- Remind her to slow her breathing down. Just taking in long, deep breaths—inhale for five seconds, exhale for five seconds—can be very calming.

- Encourage her to moan during the contractions and rest in between. Screaming isn’t very effective in coping with pain, and neither is the patterned breathing taught in many childbirth prep systems. Instead, go for low, growly, guttural sounds—deep and loud—the kind of sounds you’d make if you tried to lift a car. This is no time to be dainty or to worry about what the people in the next room—or on the next floor—will think. They’re probably making plenty of noises of their own.

- Help her relax. People coping with pain often clench their jaws, make fists, tense their shoulders, or hold their breath. None of this helps. In fact, it does more harm than good.

- Get in her face and be direct. ( This may seem a little aggressive, but it really does work.) In early labor, lock eyes with her and tell her what to do: unclench your jaw, un-fist your hands, drop your shoulders, breeeeeeathe. . . . As labor progresses, skip the words and just show her what you want her to do by letting your body melt, unclenching, and moaning. Doing this is especially important between contractions. Staying tense—or tensing up in anticipation of the next uterus-wrenching contraction—will make it harder for her to recover during those all-too-brief breaks.

- Offer sips of water, ice chips, and cold compresses.

- Offer a massage. Back, hands, feet, or whatever she’d like (if she wants anything at all). Sometimes, when massage is annoying, sustained counterpressure can be just the ticket. Ask her which helps more: high or low on the back, or closer to the tailbone.

- Verbal anesthesia. Tell her she’s doing a great job—it means a lot more coming from you than from a nurse she doesn’t know. Simple things like “Great job!” or “Stay with it” are remarkably effective.

- Make sure she hits the bathroom at least once every hour. If she’s not peeing that often, she’s not drinking enough.

- Get her up and moving around. Being upright, if at all possible, makes gravity kick in and help the baby descend. Walking around keeps her body in motion and maximizes the effect that relaxin (a hormone that does just that) can have on the pelvic joints. You may be able to do this during the contractions in early labor. But once she’s deep into active labor, do it between contractions.

STAGE 1

PHASE 1 (EARLY OR LATENT LABOR) Although the contractions are fairly mild at this point, you should do everything you can to make your partner as comfortable as possible (back rubs, massages, and so forth). Some women may tell you exactly what they want you to do; others may feel a little shy about making any demands. Either way, ask her regularly what you can do to help. And when she tells you, do it. If taking a walk makes her feel better, go with her. If doing headstands in the living room is what she wants to do (fairly unlikely at this point), go ahead and spot her. The easiest way to tell whether she’s really in labor is to watch the contractions. If they’re getting longer, stronger, and closer together, it’s the real deal. If not, take it easy. You should be recording the contractions anyway, because when you call her practitioner to ask whether to come down to the hospital, he’ll want to know what’s been going on.

During early labor, it’s okay for your partner to keep her strength up, so light eating—salads, soups, and so on—is fine. And drinking water during early labor is crucial. No matter what your partner does, you should eat and drink something. You need to keep your energy level up too, and you’re not going to want to try to make a dash to the snack bar between contractions. Finally, try to get some rest. Don’t be fooled by the adrenaline rush that will hit you when your partner finally goes into labor. You’ll be so excited that you’ll feel you can last forever. But you can’t. She’s got some hormones (and pain) to keep her going; you don’t.

PHASE 2 (ACTIVE LABOR) One of the symptoms of second-phase labor is that your partner may seem to be losing interest in just about everything—including arguing with you about when to call the doctor. After my wife’s contractions had been two to three minutes apart for a few hours, I was encouraging her to call. She refused. Many women, it seems, “just know” when it’s time to go. So chances are, if she tells you “it’s time,” you should grab your car keys. That said, you’re going to be in regular contact with your partner’s practitioner, and if he or she thinks it’s time to come in, that trumps your partner’s desires to stay home.

One of the biggest hints as to whether your partner is in active labor is whether she can walk and talk through the contractions. If not, she most likely is. If you’re still not sure whether the second phase has started, here’s a pretty typical scenario that may help you decide:

| YOU: | Honey, these contractions have been going on like this for three hours. |

| I think we should head off to the hospital. | |

| HER: | Okay. |

| YOU: | Great. Let’s get dressed, okay? |

| HER: | I don’t want to get dressed. |

| YOU: | But you’re only wearing a nightgown. How about at least putting on some shoes and socks? |

| HER: | I don’t want any shoes and socks. |

| YOU: | But it’s cold out there. How about a jacket? |

| HER: | I don’t want a jacket. |

Get the point?

Another common symptom of second-phase labor is an uncharacteristic loss of modesty. Birth-class instructor Kim Kaehler says she can always tell what stage of labor a woman is in just by looking at the sheet on the bed (when the pregnant woman is in it). If she’s in phase one, she’ll be covered up to her neck; in phase two, the sheet is halfway down; by phase three (see below), the sheet’s all the way off.

Once active labor has started, your partner shouldn’t eat anything unless her doctor specifically says that it’s okay (she probably won’t be allowed to eat anything after getting admitted to the hospital). If she ends up needing any medication or even a Cesarean, food in her stomach could complicate matters.

PHASE 3 ( TRANSITION) Whenever laboring women are portrayed in TV shows, they almost always seem to be snapping at their husband or boyfriend, yelling things like “Don’t touch me!” or “Leave me alone, you’re the one who did this to me.” I think I’d internalized those stereotypes, and by the time we got to the hospital I was really afraid that my wife would behave the same way when she got to the transition stage, blame me for the pain, and push me away. Fortunately, it never happened. The closest we ever came was when my wife was in labor with our second daughter. The only place she could be comfortable was in the shower, and for a while I was in there with her, trying to talk her through the contractions as I massaged her aching back. Then she asked me to leave the bathroom for a while. Sure, that stung a minute —I felt I should be there with her—but it was clear that she had no intention of hurting me.

Unfortunately, not every laboring woman manages to be as graceful under pressure. If your partner happens to say something nasty to you or throws you

unceremoniously out of the room for a while, you need to imagine that while she’s in labor her mind is being taken over by an angry rush-hour mob, all trying to push and shove their way onto an overcrowded subway train. Quite often, the pain she’s experiencing is so intense and overwhelming that the only way she can make it through the contractions is to concentrate completely on them. Something as simple and well-meaning as a word or a loving caress can be terribly distracting.

So what can you do? Whatever she wants. Fast. If she doesn’t want you to touch her, don’t insist. Offer to feed her some ice chips instead. If she wants you to get out of the room, go. But tell her that you’ll be right outside in case she needs you. If the room is pitch black and she tells you it’s too bright, agree with her and find something to turn off. If she wants to listen to the twenty-four-hour Elvis station, turn it on. But whatever you do, don’t argue with her, don’t try to reason with her, and above all, don’t pout if she swears at you or calls you names. She really doesn’t mean to, and the last thing she needs to deal with at this moment of crisis is your wounded pride.

STAGE 2: PUSHING

Up until the pushing stage, I thought I was completely prepared for dealing with my wife’s labor and delivery. I was calm, and, despite my occasional feelings of inadequacy, I knew what to expect almost every step of the way. The hospital staff was supportive of my wanting to be with my wife through every contraction. But when the time came to start pushing, they changed. All of a sudden, they were in control. The doctor was called, extra nurses magically appeared, and the room began to fill up with equipment—a scale, a bassinet, a tray of sterilized medical instruments, a washbasin, diapers, towels. (We happened to be in a combination labor / birthing room; if, in the middle of pushing, you find yourself chasing after your wife, who’s being rushed down the hall to a separate delivery room, don’t be alarmed. It may feel like an emergency, but it probably isn’t.)

The nurses told my wife what to do, how to do it, and when. All I could do was watch —and I must admit that at first I felt a little cheated. After all, I was the one who had been there right from the beginning. My baby was about to be born. But when the most important part finally arrived, it looked like I wasn’t going to be anything more than a spectator. And unless you’re a professional birthing coach or a trained labor and delivery nurse, chances are you’re going to feel like a spectator, too.

As I watched the nurses do their stuff, I quickly realized that simply holding your partner’s legs and saying, “Push, honey: that’s great” isn’t always enough. Recognizing a good, productive push, and, more important, being able to explain how to do one —“Raise your butt . . . lower your legs . . . keep your head back . . . curl up around your baby like a shrimp . . .”—are skills that come from years of experience.

But just because you feel like a spectator doesn’t mean you actually have to be one. Your partner needs you to be there, to support her, to encourage her— not in another corner of the room or hiding behind a camera, but right there with her. If you back away at this critical time, she may feel abandoned— even though she’s surrounded by professionals. So let the medical team take the lead, but hang in there and ask them how you can be involved (ideally this was a question you should have asked when you first got to the hospital. See “Checking Things Out When You’re Checking In” on page 240 for more).

STAGE 2: BIRTH

Intellectually, I knew my wife was pregnant. I’d been to all the appointments and I’d heard the heartbeat, seen the ultrasound, and felt the baby kicking. Still, there was something intangible about the whole process. And it wasn’t until our baby started “crowning” (peeking her hairy little head out of my wife’s vagina) that all the pieces finally came together.

At just about the same moment, I also realized that there was one major advantage to my having been displaced during the pushing stage: I had both hands free to “catch” the baby as she came out—and believe me, holding my daughter’s hot, slimy, bloody little body and placing her gently at my wife’s breast was easily the highlight of the whole occasion.

If you think you might want to do this, make sure you’ve worked out the choreography with your doctor and the nurses before the baby starts crowning. (See “Birth Plans” on pages 197–202 for more information.)

Your partner, unfortunately, is in the worst possible position to see the baby being born. Most hospitals, however, have tried to remedy this situation by making mirrors available. Still, many women are concentrating so hard on the pushing that they may not be interested in looking in the mirror.

If you were expecting your newborn to look like the Gerber baby, you may be in for a bit of a shock. Babies are generally born covered with a whitish coating called vernix. They’re sometimes blue and frequently covered with blood and mucus. Their eyes may be puffy, their genitals swollen, and their backs and shoulders may be covered with fine hair. In addition, the trip through the birth canal has probably left your baby with a cone-shaped head.

All in all, it’s the most beautiful sight in the world.

After the Birth

THE BABY

Your baby’s first few minutes outside the womb are a time of intense physical and emotional release for you and your partner. At long last, you get to meet the unique little person you created together. Your partner may want to try nursing the baby (although most newborns aren’t hungry for the first twelve hours or so), and you will probably want to stroke his or her brand-new skin and marvel at his or her tiny fingernails. But depending on the hospital, the conditions of the birth, and whether or not you’ve been perfectly clear about your desires, your baby’s first few minutes could be spent being poked and prodded by doctors and nurses instead of being held and cuddled by you.

One minute after birth, your baby will be given an APGAR test to allow the medical staff a quick take on your baby’s overall condition. Created in 1953 by Dr. Virginia Apgar, the test measures your baby’s Appearance (skin color), Pulse, Grimace (reflexes), Activity, and Respiration. A nurse or midwife will score each category on a scale of 0 to 2. (A bluish or pale baby might get a 0 for color while a very pink one would get 2; a baby who’s breathing irregularly or shallowly might get a 0 for respiration while one who’s breathing well, or crying loudly, would get a 2.) Most babies score in the 7 to 9 range (just on principle, almost no one gets a 10—unless it’s the child of someone the medical team knows). The test will be repeated at five minutes after birth.

Shortly after the birth, your baby will need to be weighed, measured, given an ID bracelet, bathed, diapered, footprinted, and wrapped in a blanket. Some hospitals also photograph each newborn. After that, most hospitals (frequently as required by law) apply silver nitrate drops or an antibiotic ointment to your baby’s eyes as a protection against gonorrhea. Although these procedures should be done within one hour of birth, ask the staff if they can hold off for a few minutes while you and your partner get acquainted with your baby.

If, however, your baby was delivered by C-section, or if there were any other complications, the baby will be rushed off to have his or her little lungs suctioned before returning for the rest of the cleanup routine (see pages 263– 65 for more on this).

Seeing the Baby

Some hospitals have very rigid rules regarding parent/infant contact—feeding may be highly regulated and the hours you can visit your child may be limited. Others are more flexible. The hospitals where all three of my children were born no longer have a nursery (except for babies with serious health problems). Healthy babies are expected to stay in the mother’s room for their entire hospital stay. There are even hospitals that permit the new father to spend the night with mom and baby. Check with the staff of your hospital to find out their policy.

THE PLACENTA

Before our first child was born it had simply never occurred to me (or to my wife, for that matter) that labor and delivery wouldn’t end when the baby was born. While you and your partner are admiring your new family member, the placenta—which has been your baby’s life support system for the past five months or so—still must be delivered. Your partner may continue to have mild contractions for anywhere from five minutes to about an hour until this happens. The strange thing about this stage of the delivery is that neither you nor your partner will probably even know it’s happening—you’ll be much too involved with your new baby.

Once the placenta is out, however, you need to decide what to do with it. In this country most people never even see it, and those who do just leave it at the hospital, where it will either be destroyed or, more likely, sold to a cosmetics company (there are actually a surprising number of placenta-based beauty products). But in many other cultures, the placenta is considered to have a permanent, almost magical bond with the child it nourished in the womb, and disposal is handled with a great deal more reverence. In fact, most cultures that have placenta rituals believe that if it is not properly buried, the child—or the parents, or even the entire village—will suffer some terrible consequences.

In rural Peru, for example, immediately after the birth of a child, the father is required to go to a far-off location and bury the placenta deep enough so that no animals or people will accidentally discover it. Otherwise, the placenta may become “jealous” of the attention paid to the baby and may take revenge by causing an epidemic.

In some South American Indian cultures, people believe that a child’s life can be influenced by objects that are buried with its placenta. According to researcher J. R. Davidson, parents in the Qolla tribe “bury miniature implements copied after the ones used in adult life with the placenta, in the hopes of assuring that the infant will be a good worker. Boys’ placentas are frequently buried with a shovel or a pick, and girls’ are buried with a loom or a hoe.” In the Philippines some mothers bury the placenta with books as a way of ensuring intelligence.

But placentas are not always buried. In ancient Egypt, pharaohs’ placentas were wrapped in special containers to keep them from harm. And a wealthy Inca in Ecuador built a solid-gold statue of his mother—complete with his placenta in “her” womb.

Even today, the people of many cultures believe that placentas have special powers. A lot of women—including many in the United States—believe that placentophagy (ingesting cooked or dried placenta) can reduce or eliminate postpartum depression. In other parts of Peru placentas are burned, the ashes are mixed with water, and the mixture is then drunk by the babies as a remedy for a variety of childhood illnesses. Traditional Vietnamese medicine uses placentas to combat sterility and senility, and in India, touching a placenta is supposed to help a childless woman conceive a healthy baby of her own. In China, some believe that breastfeeding mothers can improve the quality of their milk by drinking a broth made of boiled placenta, or speed up labor by eating a piece of it dried.

This sort of placenta usage isn’t limited to non-Western cultures. In medieval Europe, if a child was born with a caul (with the amniotic membranes over his head), the placenta would be saved, dried, and fed to the child on his tenth birthday. If it wasn’t done, it was believed that the child might become a vampire after death.

Whatever you and your partner decide to do, it’s probably best to keep it a secret—at least from the hospital staff. Some states try to regulate what you can do with a placenta and may even prohibit you from taking it home (although if you really want to, you can probably find a sympathetic nurse who will pack it up for you). We deliberately left our first daughter’s placenta at the hospital. But we stored the second one’s in our freezer for a year before burying it, along with the placentas of some of our friends’ children, and planting an apple tree above them. Twelve years later, at her bat mitzvah, we ate some of the apples from that tree. And yes, they tasted perfectly fine.

Dealing with Contingencies

Unfortunately, not all labors and deliveries proceed exactly as planned. In fact, most don’t. The American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists estimates that more than 30 percent of babies are born by Cesarean section. And well over half of mothers who deliver vaginally are medicated in some way. As with so many other aspects of your pregnancy experience, having good, clear information about what’s really going on and what the options are during labor and delivery will help you make informed, intelligent decisions about how to handle the unexpected or the unplanned. The key to getting the information you need is to ask questions—and to keep on asking until you’re completely satisfied. Find out about the risks, the benefits, and the effects on your partner, as well as on the baby. The only exception to this rule is when there’s a clear medical emergency. In that case, save your questions for later.

Here are a few of the contingencies that can come up during the birth and how they might affect you, your partner, and the baby.

PAIN

If you’ve taken a traditional Lamaze or Bradley childbirth class or read many pregnancy books (and even if you haven’t), you and your partner may be planning to have a “natural” (medication-free) childbirth. Unfortunately, natural childbirth often sounds better—and less painful—than it actually turns out to be. According to Marci Lobel, Ph.D., director of the Stony Brook Pregnancy Project at Stony Brook University, “Popular books written for pregnant women often understate the degree of pain experienced during birth, and may overstate the effectiveness of childbirth preparation in reducing pain.” And think about all those childbirth images you’ve seen in movies and on TV. The pain looks unbearable, but it never lasts any more than a few minutes.

Because your partner is the one who is experiencing the physical pain, defer to her judgment when considering ways to manage it. This doesn’t mean, however, that you don’t have anything to say about the issue. As labor progresses, your partner will become less rational and less able to make big decisions. So it’s up to you to be her advocate, to make sure she has the kind of birth she wants (or at least as close to it as you can get). That’s why I strongly suggest that the two of you have some thorough discussions about her attitude toward medication before she goes into labor, so you know whether she’d want you to suggest it when you get concerned or wait until she requests it. You might also want to come up with a code word that means “I really want drugs NOW.” Some women may scream for the doctor (or you) to “do something about the pain” but not really want drugs.

If you do end up having a discussion about medication sometime during labor, make sure you do it in the most supportive possible way. It’s painful to have to watch the one you love suffer, but starting an argument when she’s in the middle of a contraction isn’t a smart idea (and you’re not going to resolve anything anyway). Despite the fact that most women get some kind of chemical pain relief, many women feel that taking medication is a sign of weakness, or that they’ve failed—as women and as mothers. It’s as if having an unmedicated childbirth is part of the transition to womanhood. In addition, some childbirth preparation methods view medication as the first step along a path that ultimately leads to Cesarean section. Neither of these scenarios is, by any stretch of the imagination, the rule. If you check into the hospital with a pregnant partner, and leave a few days later with a no-longer-pregnant partner and a healthy baby, you win. It shouldn’t matter at all how it happened, as long as it was medically necessary (and it almost always is).

I’m not suggesting that your partner should use—or that she’ll even need— pain medication. But whatever you do, knowing a little about your options is always a good idea (see “Whew! That’s a Relief ” on pages 252–54).

Whew! That’s a Relief

There is, as Sarah McMoyler puts it, “a big difference between coping and suffering.” Despite all the emphasis on natural (unmedicated) childbirth these days, more and more women seem to be opting for some kind of chemical pain relief during labor and childbirth. Actually, there’s evidence that women have been searching for alternatives to natural birth ever since they were first introduced in the 1840s, says obstetric anesthesiologist Donald Caton, author of What a Blessing She Had Chloroform: The Medical and Social Response to the Pain of Childbirth from 1800 to the Present.

Women today have literally dozens of options that fall into to two basic categories: regionals, which reduce or eliminate pain only in certain parts of her body, and systemics, which will relax her whole body.

REGIONALS

These medications work only on specific regions of the body, hence the name. The most common of all regionals (and of all childbirth-related pain medication, for that matter) is the epidural, which is usually administered during active labor (the second phase of the first stage), when the pain is greatest.

Your partner will have to lean over or curl up on her side while an anesthesiologist numbs her lower back; inserts a medication-carrying catheter into the “epidural space” that’s just outside the spinal cord, between it and the membrane that surrounds it; and tapes it to her back.

Epidurals are widely considered the safest and most effective labor painkiller available. They kick in almost immediately and will block the pain of your partner’s contractions while still leaving her awake and alert. Perhaps most important, they don’t “cross the placenta” (affect the baby).

Until just a few years ago, epidurals carried the risk of decreasing maternal blood pressure or reducing the woman’s ability to feel when to push (which could slow down the course of labor), as well as causing headaches and nausea. And a lot of people thought that epidurals increased the risk of a Cesarean or instrument birth. But as of recent years, anesthesiologists are better able to fine-tune the dose, all but eliminating these risks. A growing body of research shows that women who have epidurals aren’t any more likely to have a C-section or instrument birth; better yet, epidurals may actually move labor along more quickly. By blocking the pain, the woman can get a well-deserved break (sometimes even a nap), so when it’s time to push, she’ll be refreshed and strong.

Another problem with epidurals used to be that, since they numb the lower body, women were confined to their beds for the duration. But a new “walking epidural” is being introduced that will offer the same pain relief and allow at least some mobility, so ask your partner’s practitioner whether it’s available at your hospital.

While you’re asking about the latest innovations, find out whether PCEA (patient-controlled epidural anesthesia) is a possibility. The way it works is that the anesthesiologist gets the epidural up and running and then allows the patient to adjust the amount of medication she gets (within reason). As with any kind of patient-controlled medication, patients don’t use nearly as much as a doctor would have given them. Seems that just knowing relief is a button-push away decreases the need.

Other less-common regional options include the pudendal block (an injection given into each side of the vagina that deadens the vaginal opening), the paracervical block (an injection into the area around the cervix that relieves pain from dilation and contractions), the spinal block (injections into the fluid around the spinal cord in the lower back—it’s similar to an epidural but doesn’t last as long and carries a slightly greater risk of complications).

SYSTEMICS

This type of whole-body pain relief includes sedatives, tranquilizers, and narcotics such as Demerol and fentanyl, which are usually given as injections or added to existing intravenous (IV) lines. It also includes general anesthesia, which knocks the recipient out completely and is rarely used, except when performing an emergency Cesarean.

Besides taking the edge off the contractions almost immediately, one of the major advantages to systemic medications is that your partner can use them from the very beginning of labor. They may relieve a lot of her anxiety and won’t usually have much of an impact on her ability to push or sense her contractions.

On the downside, though, these medications affect your partner’s entire body and can cause a wide variety of side effects, including drowsiness, dizziness, and nausea. In some ways, these drugs do less to remove the pain than to make your partner simply stop caring about it. Even worse, since they go right into your partner’s bloodstream, they also “cross the placenta,” meaning that at birth, the baby could be drowsy, unable to suck properly for a short while, or, in rare cases, unable to breathe without assistance. Fortunately, those symptoms go away pretty quickly on their own. There’s also a drug, Narcan, that can reverse these side effects.

Interestingly, your partner’s use—or nonuse—of pain medication may have an impact on you as well. For most expectant dads, anything that makes our partners more comfortable and hurt less is great. But besides that, medication can also reduce the stress and make the whole experience more pleasant for us. In a study of how a laboring woman’s use of epidurals affects her partner, Italian researchers Giorgio Capogna and Michela Camorcia found that “fathers whose partners did not receive epidural analgesia felt their presence as troublesome and unnecessary.” On the other hand, when the mom did have an epidural, fathers’ feelings of helpfulness were tripled. They were also more involved during the labor and felt less anxiety and stress.

For other guys, though, reducing her pain may be a source of disappointment—in a twisted, yet understandable, sort of way. We’re supposed to be there to help her through the pain, the thinking goes, but if she doesn’t need us to do that, maybe she doesn’t need us at all. In other words, reducing the pain may also reduce the father’s sense of usefulness and importance. A word of advice: if your partner wants some pain medication, support her. There are plenty of other ways to be helpful.

EXHAUSTION

Pain isn’t the only reason your partner might need some chemical intervention. In some cases, labor is progressing so slowly (or has been stalled for so long) that your practitioner may become concerned that your partner will be too exhausted by the time she needs to push. This was exactly what happened during the birth of my middle daughter. After twenty hours of labor and only four centimeters of dilation, our doctor suggested pitocin (a drug that stimulates contractions) together with an epidural (see pages 252–53). This chemical cocktail removed the pain of labor while allowing my wife’s cervix to dilate fully and quickly. I’m convinced that this approach actually prevented a C-section by allowing my wife a well-deserved breather before she started pushing.

INDUCED LABOR

Any time after forty weeks of pregnancy, your baby is officially fully baked. They don’t always get this piece of news, though, and are sometimes reluctant to come out. There are all sorts of supposedly surefire ways to bring on labor, and you’ll start hearing every one of them as soon as you mention that the baby is late: eat certain kinds of salad dressings or vinegars, eat spicy food, go on long walks, drink cod-liver oil, and more. There is actually some research suggesting that sex may help: nipple stimulation and your partner’s orgasm may trigger some contractions, plus semen has prostaglandin in it, which is similar to the gel or pill that’s used to induce labor. And, as Lissa Rankin puts it, “Messing around with the cervix can trigger contractions and get things started.” But before you try any kind of home remedy, check with your practitioner to make sure it’s safe.

If your partner’s due date is long past, your practitioner may decide that things have gone on long enough (this will happen about two months after your partner reached the same conclusion), and he’ll suggest jump-starting the labor with pitocin (a chemical version of oxytocin) or Cytotec (a type of prostaglandin). Some people claim that pitocin results in more painful labors and increases the Cesarean rate, but just as many disagree, saying that all pitocin does is produce normal labor.

Other Common Birth Contingencies

FORCEPS OR VACUUM

If your partner’s cervix is completely dilated and she’s been pushing for a while, but the baby refuses to budge, her practitioner may suggest using forceps—long tongs with scoops on the end (imagine salad tongs that are big enough to pick up a coconut)—to help things along. It used to be that the very word forceps struck fear into every expectant parent’s heart. But today they’re used only to gently grasp the baby’s head to guide it through the birth canal. Some forceps deliveries will leave the baby with bruises in the temple or jawline area for a few days or a week. In very rare instances, permanent scarring or other damage can occur. In addition, your partner will need additional medication and may require a larger-than-normal episiotomy (see below).

In some cases, instead of forceps, doctors may be able to use a vacuum-type suction device that attaches to the top of the baby’s head, to move the baby around in the same way.

The doctor may also suggest using forceps or vacuum if the baby is in distress and a vaginal birth needs to be sped up, or if your partner is too exhausted (or medicated) to push effectively. Keep in mind that most OB/ GYNs are trained in either forceps or vacuum extraction, not both. Used appropriately, forceps and/or suction can sometimes prevent the need for a C-section.

EPISIOTOMY

An episiotomy involves making a small cut in the perineum (the area between the vagina and the anus) to enlarge the vaginal opening and allow for easier passage of the baby’s head. Only a decade or so ago, the episiotomy rate for women delivering for the first time under an obstetrician’s care was 70 to 90 percent. The thought was that a controlled cut would help women avoid bowel, urinary, and sexual problems after delivery. But recent research has shown that episiotomy may actually increase the risk of those problems. Today, the episiotomy rate is under 20 percent. Overall, about 70 percent of first-time moms will have a small, spontaneous tear. The phrase “spontaneous tear” sounds absolutely frightening to me, but it turns out that with an episiotomy, the flesh can tear even more. So as contradictory as it might seem, those tears are preferable (and less painful) than a routine episiotomy. But the procedure may be legitimately indicated if:

- The baby is extremely large, and squeezing through the vagina might harm the baby or your partner.

- Forceps are used.

- The baby is breech (see below).

- The practitioner can see that numerous tears are going to happen.

BREECH PRESENTATION

If a baby is breech it means that the head is up and the butt or feet are pointing down (only 3 to 4 percent of single babies are born this way, but about a third of all twins are). Actually, there are several different types of breech births: frank breech means that the baby’s feet are straight up next to his head and the baby will come out butt first. Complete breech means that the butt is down and the baby is “sitting” cross-legged. Footling breech means that one or both feet are pointing down. There’s little you can do to prevent your baby from getting into any position he or she wants to. But most doctors in the United States will not deliver breech babies vaginally. This means that if the baby can’t be turned, usually through a nonsurgical process called “external version,” it’s going to be delivered by C-section.

ELECTRONIC FETAL MONITORING (EFM)

EFMs have been around since the early 1970s, and today, they’re used in 85 percent of births. They come in two flavors: external and internal.

The external variety is a rather complicated machine—complete with graphs, digital outputs, and high-tech beeping—that gets strapped to your partner’s abdomen. It’s used to monitor your baby’s heartbeat and your partner’s contractions.

Fetal monitors are really pretty cool. Properly hooked up, they are so accurate that by watching the digital display, you’ll be able to tell when your partner’s contractions are starting—even before she feels them—and if she has an IUPC (intrauterine pressure catheter, which is a tube that lies next to the baby and measures contraction strength), you’ll actually be able to tell how intense they’ll be. In one fascinating study, researchers Kristi Williams and Debra Umberson found that most expectant fathers like fetal monitors—partly because by getting information we feel like we’re really involved. “By observing and communicating the changing intensity of the contractions, these men believed that they were able to provide valuable information to their wives,” they wrote. “This creates a role for husbands to play in labor and delivery that is, from their perspective, more important than merely providing support and encouragement.”

Notice the use of the phrases “these men believed” and “from their perspective.” Williams and Umberson also found that women often perceived the monitors as a nuisance and the information they provided not particularly helpful. After all, they’re getting the same information anyway, but in a slightly different way: it hurts like hell. And the monitors don’t always reflect reality. The contraction may look like it’s over on the screen, but it can be far from over for her.

So be careful. These monitors may help you guide your partner through the contraction. But think long and hard before saying something like “Ready, honey? Here it comes—looks like a big one” (unfortunately, I know whereof I speak).

In many hospitals, laboring women are routinely hooked up to external fetal monitors as soon as they check in. The nurses will take readings for half an hour or so and, assuming all is well with Mom and baby, they’ll take the monitor off and just hook it back up every hour during labor. If, however, she has an epidural or is on pitocin, she’ll need continuous monitoring. Ditto when it comes time to push.

Internal fetal monitors come in two varieties: an electrode attached to the baby’s scalp, and the IUPC mentioned above. If your practitioner feels that it’s important to keep closer tabs on the baby’s heart rate, your partner will get one or both of these internal monitors.

less there’s some compelling reason why you need it (if there have been signs of fetal distress, for example), you and your partner will be a lot better off with as little monitoring as possible. Here’s why:

- There’s too much room for misinterpreting the results. One study had four doctors interpret fifty different tracings. The four concurred only 22 percent of the time. Worse yet, two months later, when the same docs were asked to evaluate the same tracings, they interpreted more than 20 percent of them differently.

- It can scare the hell out of you. When my wife was hooked up to a fetal monitor during her first labor, we were comforted by the sound of the baby’s steady, 140-beats-per-minute heartbeat. But at one point the heart rate dropped to 120, then 100, then 80, then 60. Nothing was wrong—the doctor was just trying to change the baby’s position—but hearing her little heart slow down that much nearly gave my wife and me heart attacks. If your partner’s practitioner believes that monitoring is medically necessary, turn the volume down (better yet, all the way off ).

- Fetal monitoring was originally implemented in the hope that it would prevent cerebral palsy. But despite the very best of intentions, it has led to an increase in C-sections and instrument deliveries. And, ironically, it didn’t do anything for cerebral palsy either—the rate has stayed the same for the past fifty years. The moral of the story is that the doctor might see something happen to the baby on the monitor, get worried, and operate. In a lot of cases, what looks like fetal distress on the tracing (the printout generated by the monitor) ends up going away on its own.

Notes: