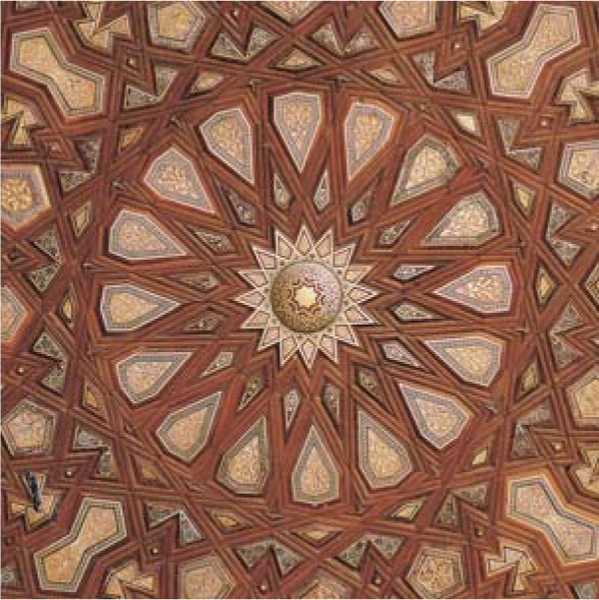

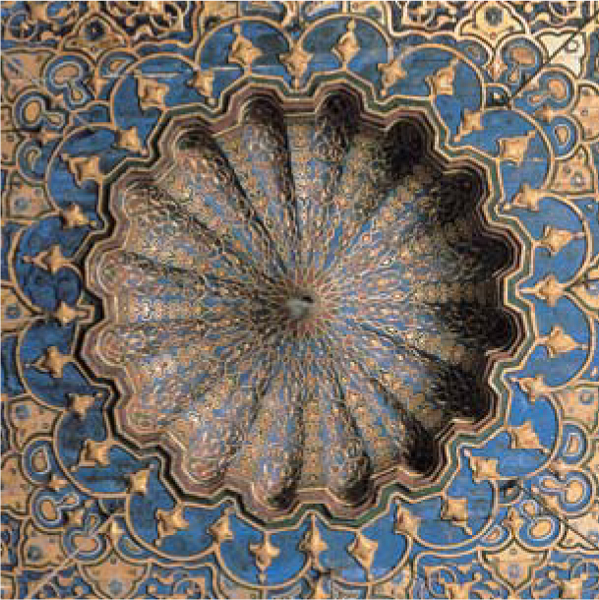

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, mihrab, Cairo.

Salah El-Bahnasi, Medhat El-Menabbawi, Mohamed Abd El-Aziz, Mohamed Hossam El-Din, Tarek Torky

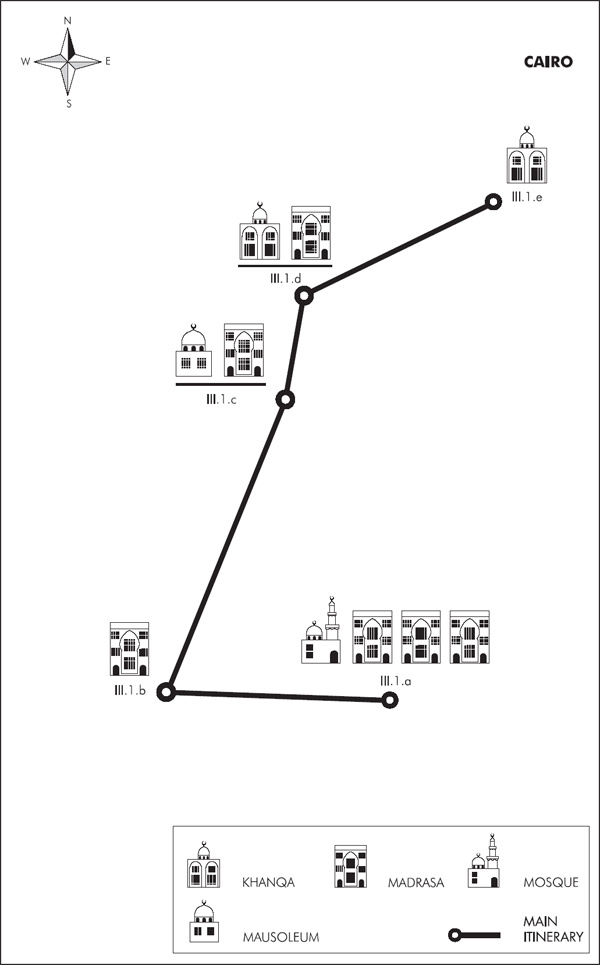

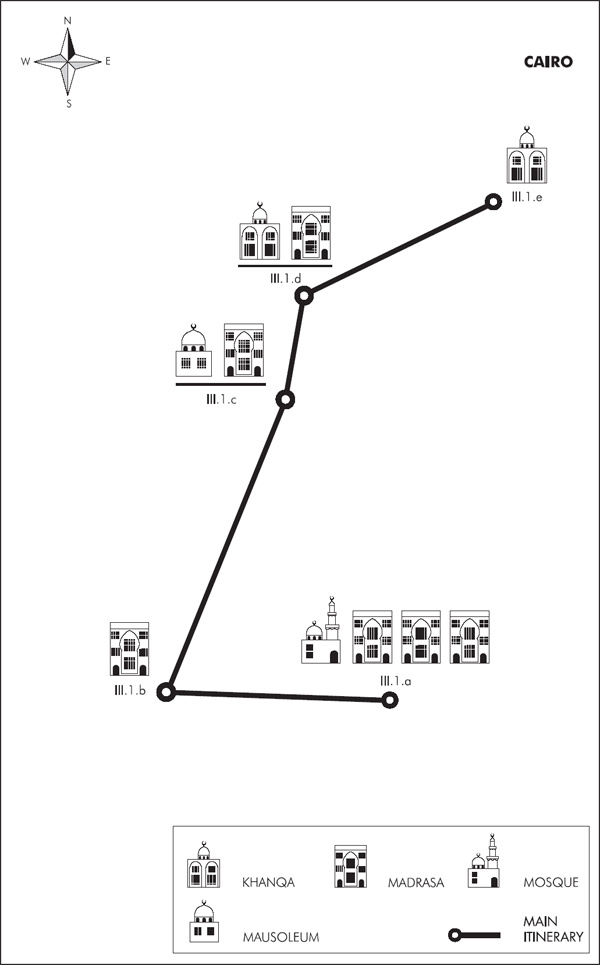

III.1.a Mosque of al-Azhar and its Mamluk Madrasas

III.1.b Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri

III.1.c Complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun

III.1.d Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq

III.1.e Khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, mihrab, Cairo.

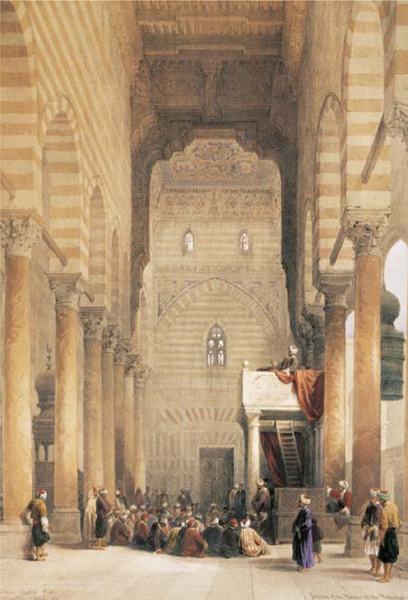

Inside the Mosque of Sultan al-Ghuri, Cairo (D. Roberts, 1996, courtesy of the American University of Cairo).

The Mamluk era saw the rapid growth of Cairene educational institutions to which numerous learned men and academics were attracted. With the construction of institutions such as madrasas and khanqas, sultans and amirs contributed significantly to the growth of intellectual activity.

With the Crusader threat over and the risk of Mongol invasion contained, Egypt enjoyed a period of great security. She proved an attractive destination for learned men from all four corners of the Islamic world, in particular for those arriving from her eastern and western regions, areas that had suffered at the hands of both the Mongols and Crusaders. At the same time, the Christian Reconquest of the Muslim territories of Al-Andalus (Spain) was gaining ground, causing many Muslims to emigrate to a safe haven in Egypt.

Conditions were to coalesce such that Egypt became “place of residence for ulemas and a resting place for the most virtuous travellers” as al-Suyuti (b. 849/1445) writes. In the 8th/14th century al-Balawi the Maghrebi traveller, and one of the great Cadis of al-Andalus to visit Cairo during the reign of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, described Egypt as: “the source of knowledge” and that “while in Cairo there was nothing more than what is known as al-maristan (III.1.c) it alone is sufficient, for this majestic palace was among the most astounding palaces, for its beauty, elegance and spaciousness”.

In the first half of the 8th/14th century the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta also vis-sited Egypt. He observed great activity in the field of sciences recording what he saw in his book of travels. The competition between sultans and amirs to surpass each other with each new building and the importance of the khanqas in the spread of scientific knowledge resulted in new advances. Each khanqa was devoted to a different ethnic group of Sufis (the majority of non-Arab origin) who were Muslim mystics of culture, instruction and good manners and who attempted to return to their original spirituality.

The famous Tunisian philosopher, Ibn Khaldun, came to Egypt where he lived until his death (b.784/1382, d.809/1406). He finished writing his works there and took on the administration of the khanqa of Sultan Baybars II al-Gashankir (III.1.e) in the year 792/1389 writing the following about Egypt:

“… palaces and iwans shine on her face, khanqas and madrasas flourish in harmony, and the full moon and stars shine on her ulemas. Thus the waqfs multiplied, and those thirsty for knowledge grew in numbers, her masters encouraged by the high wages, and people came to her from Iraq and the Maghreb in search of science”.

In the time of the Mamluk Sultans, learned men came from Egypt and were warmly received by her governors, who offered friendship and hospitality and provided accommodation in accordance with their visitor’s status. History books mention Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun’s friendship with the historian Abu al-Fida and record how Sultans Barquq, al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, Jaqmaq, Barsbay, Qaytbay and al-Ghuri were passionately interested in the meetings of learned men and writers. Barsbay had the historian Badr al-Din al-‘Ayni sit next to him and tell him the history of the Ottomans while al-Ghuri showed great generosity towards learned men and their sciences. The founding documents of waqfs testify to this interest. Those who made donations to the pious foundations specified in the documents exactly how their contributions were to be invested and the salaries that learned men and masters were to receive.

This growing interest in learning resulted in the appearance of numerous encyclopaedias, both in areas of the humanities and in applied sciences. Among them we find historical encyclopaedias such as al-Suluk li-ma‘rifat duwal al-muluk (History of the Ayyubids and the Mamluks) by al-Maqrizi; al-Nujum al-zahira fi muluk Misr wa al-Qahira (History of Egypt from the Arab Conquest to the Mamluk Era) by Abu al-Mahasin Ibn Taghri Bardi; Bada’i‘ al-zuhur fi waqa’i‘ al-duhur (History of Egypt in the Mamluk Period, with particular reference to Cairo) by Ibn Iyas. There are translations including Wafayat al-a‘yan (Biographical Dictionary of Noted Egyptian Ulemas and Learned Men from the Muslim World) by Ibn Khalikan; al-Daw’ al-lami‘ li-ahl al-qarn al-tasi‘ (Bio-graphical Dictionary of Egyptian Ulemas and Learned men from the Mamluk Period) by al-Sakhawi; al-Nahl al-safi by Ibn Taghri Bardi and ‘Aqd al-juman fi tarikh ahl al-zaman by al-‘Ayni, to name but a few.

Lessons inside the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, Cairo (D. Roberts, 1996, courtesy of the American University of Cairo).

Among the literary encyclopaedias the following are most notable: Subh al-a‘cha fi sina‘at al-incha’ by al-Qalqashandi and Nihayyat al-arb fi funun al-adab (History of Egypt and the Islamic East from the Beginning of Islam to the Mamluk Period) by al-Nuwayri. In addition, Ibn Manzur collated his dictionary Lisan al-‘arab and al-Busiri wrote his popular poetic work al-Kawakib al-durriyya fi madh khayr al-barriyya known as al-Burda. Other major works exist such as al-Intisar li-wasitat ‘aqd al-amsar and Masalik al-absar fi mamalik al-amsar by al-‘Umari on matters of geography including descriptions of different countries, their topography, the nature of their people and origins of their wealth.

Political writings include Athar al-awwal fi tadbir al-duwal by Hassan Ibn ‘Abd Allah al-‘Abbas, as well as other valuable works of which the heads of neighbouring States ordered copies.

In the sciences of religion and jurisprudence, commentaries and exegesis of the Qur’an and Sunna came to light. The most noted ones are: Fath al-bari bi-charh sahih al-bukhari by the imam Ibn Hajr al-‘Asqalani, who dictated the text in the khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir (III.1.e).

The Egyptian renaissance in the search for knowledge was not merely limited to the Humanities, but also prevailed through the many learned men well versed in medicine, astrology and other specialist fields of knowledge. Interest in astrology and astronomy was evidenced by the sobriquet “al-miqati” (he who determines the use of a time) adopted by many academics of the period. It was common knowledge by then that astronomy established the months of the year, determined the beginning of prayers as well as other religious duties such as fasting or pilgrimage, all with great precision.

Medicine was also studied in several places such as the maristan (hospital) of Qalawun (III.1.c) or the Tulunid Mosque where Sultan Lajin held classes, which in 696/1296 ten pupils attended. Such was the reputation of Egyptian doctors that Ottoman Sultan Bayazid I sent an envoy to the Mamluk Sultan Barquq requesting an experienced doctor and some medicine. Among contributions to this science in the Mamluk period is that made by Ibn al-Nafis (7th/13th century) of his description of pulmonary haematosis. The results of his studies put an end to the greatest mistake made on inter-ventricular communication by the Greek doctor Galenus (129-201). While his discoveries were completely ignored in Europe, Ibn al-Nafis had in fact anticipated two European doctors by almost three centuries; Miguel Servet, doctor and theologian (1511-1553), who confirmed the theory of pulmonary circulation and the Italian doctor and anaesthetist Realdo Colombo (1516-1559), who had refuted Galenus’ theory on cardiac physiology. Ibn al-Nafis composed his encyclopaedia al-Chamil fi al-tibb and it is said of him that not another man on the face of the earth could match him in his time.

A religious tutor known as Abu Haliqa was among the most famous doctors of the time who had studied medicine in the hospital of Qalawun. Other well-known names were the sultan’s doctor Ibn al-‘Afif, whose manuscript on prescriptions for the treatment of intestinal problems is now preserved in the Museum of Islamic Art while Shams al-Din al-Qusuni and Abu Zakariya Yahya Ibn Musa were famous for their understanding of bone disease.

The Mamluk Sultans’ great interest in medical science was closely related to treatment centres called maristan. The traveller al-Balawi, visiting Egypt in the 7th/14th century, described the Qalawun hospital furniture as rivalling that of palaces of amirs or caliphs. There was a section in the hospital for treatment using music, provision for which was set out in the waqf document as commissioned by Qalawun stipulating that: “every night four musicians were to make themselves present with their instruments to play the lute and to watch over the sick”. The singers also repeated suplications and short prayers at night from the minaret “to relieve the sick of their illnesses and insomnia”.

Al-Dumayri collated an encyclopaedia on veterinary science, Hayat al-hayawan al-kubra, in which the majority of known animals were studied and described in minute detail. Shahab al-Din Abi al-‘Abbas, who died in 684/1285, was widely recognised in these times for his scientific treatise Kitab al-istibsar fi-ma tudrikuhu al-absar on the subject of the rainbow. It was written expressly on Sultan al-Kamil’s request as he wished to send it to Emperor Frederic, and it is thought to be one of the first studies to deal with such an important subject in the field of physics. Such wealth of information provides us with a clear picture of the state of science and learning in Mamluk Egypt.

S. B., M. H. D. and T. T.

III.1.a Mosque of al-Azhar and its Mamluk Madrasas

Al-Azhar Mosque is located on al-Azhar Street in the area of the same name, opposite the Mosque of al-Husein.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00. in summer)

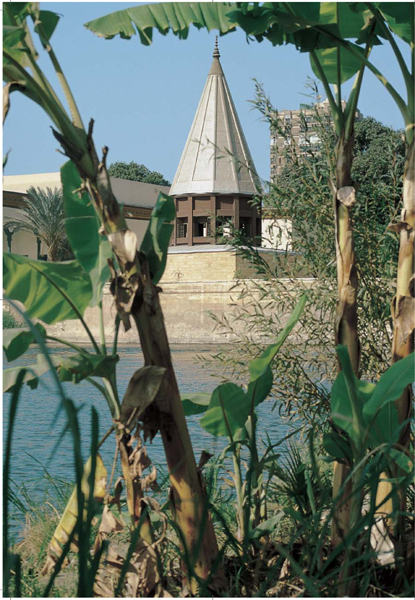

Mosque of al-Azhar, view with dome of the Madrasa of al-Gawhariyya, Cairo.

The Mosque of Al-Azhar is both the oldest and largest university in the Islamic world with students from all the Muslim countries studying there. Al-Azhar Mosque was commissioned by the Imam al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah, Prince of Believers, the fourth Fatimid Caliph and the first to govern Egypt. It was also the first mosque to be built in Cairo by General Gawhar al-Siqilli.

Work began in 359/970 and was completed two years later. As the Mosque of ‘Amr Ibn al-‘As was to Fustat, and the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun to al-Qata’i‘, so the founder intended the Mosque of al-Azhar to be to the city of Cairo, her congregational mosque. Al-Azhar was also designed for another purpose; the instruction, to a small group of pupils, of Shi‘ite jurisprudence.

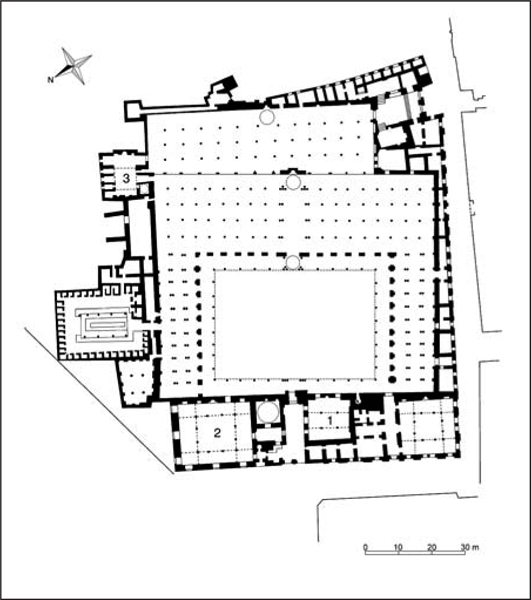

Masque of al-Azhar, plan, Cairo.

1. Madrasa of al-Taybarsiyya

2. Madrasa of al-Aqbughawiyya

3. Madrasa of al-Gawhariyya.

The building originally covered only half the surface area it occupies today though it was later enlarged, rooms were added, and successive renovations carried out until it reached its present size. The mosque was first built with a central courtyard and porticoes on three sides. The sanctuary comprised five aisles parallel to the qibla wall, while the north and south porticoes had three aisles each, the arcades around the courtyard resting on brick pillars. While the north west wall had no arcade, the main door was located in its centre, and it is believed to have projected out from the main wall. The original minaret rose up above this north west wall and another two doors were located one on the south east and another on the east walls.

The central aisle in the qibla hall, with the mihrab at the end, is wider and taller than the others. The arches of this aisle run perpendicular to the qibla wall and are decorated with Kufic inscriptions and various floral motifs, the only original decorations the mosque still preserves today. The mihrab, also dating back to the original Fatimid construction, is ornamented with Kufic inscriptions. The dome above the prayer hall is a later construction of Mamluk times, (9th/15th century) and replaces the earlier Fatimid dome. During the reign of Salah al-Din and of the Sunni Caliphs al-Azhar Mosque was closed, for it was considered a centre of propaganda of Shi’ite doctrine.

On reinstating the Abbasid Caliphate in Cairo, Sultan Baybars found affinity with the ulemas, cadis and al-faqihs and turned the Qur’an, the hadith (prophetic tradition), religious and other sciences into core subjects of education and culture.

After almost 100 years of neglect, Baybars successfully reinstated Friday prayers in the Mosque of al-Azhar in 665/1267 and restored it to its former glory of the first mosque of Cairo. Of the restoration work carried out under him, only the fine stucco around the upper part of the Fatimid mihrab still remains.

In 873/1468 Sultan Qaytbay ordered the main door to be demolished and replaced with the more ornamental one with the floral decoration and Kufic script that we see today. He also had a minaret added which rose above and to the right of the door. This intricately designed and elegantly decorated minaret is characteristic of the Qaytbay period.

Towards the end of the Mamluk era, Sultan al-Ghuri ordered a second minaret to be built, which was completed in 915/1510. Placed to the right of the minaret commissioned by Qaytbay, it is noted for its extraordinary height, the highly original blue ceramic arrows encrusted in the second section of its shaft and its double (or twin) finial, similar to that of the Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur, (I.1.f).

The minaret is characterised by its double staircases separated by a wall, which lead to each of the minaret tops crowned by bulbiform finials. Qusun (736/1336) and the Azbak al-Yusufi (900/1495) minarets are the only ones in Cairo with a double-staircase construction.

M. M.

Madrasa of al-Taybarsiyya

The madrasa is located within the mosque, to the right of the entrance. It now houses a collection of the most precious and rare manuscripts of the al-Azhar library.

Mosque of al-Azhar, Madrasa of al-Aqbughawiyya, mihrab, Cairo.

Amir ‘Ala’ al-Din Taybars, khaznadar (treasurer) and captain of the armies during the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad, had this madrasa built and consecrated as a mosque annexed to al-Azhar. It contains a watering trough and an ablutions fountain and the amir founded courses there for the al-faqihs of the shafi’i and maliki legal schools.

The gilt ceilings brought innovation to the building and the elegant marble work has a finely crafted frieze representing small mihrabs, a style of ornamentation that can be seen with even finer detail on the main mihrab. The latter dates back to the early Bahri Mamluk era, a masterpiece of Mamluk art.

Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri, minaret, Cairo.

The madrasa was completed in 709/1309 and in 1167/1753 during the Ottoman era, Amir ‘Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda had its main wall renovated.

Madrasa of al-Aqbughawiyya

The madrasa to the left of the entrance is located within the mosque founded at the beginning of the 20th century by the Khedive (or Viceroy) ‘Abbas Hilmi II. It now houses the al-Azhar library with its collection of priceless manuscripts and Qur’ans.

Amir ‘Ala’ al-Din Aqbugha, ustadar (private tutor) to al-Nasir Muhammad, had this madrasa built in 740/1340. Original elements of the construction are preserved in the entrance, qubba wall, mihrab and minaret. The minaret was the second one in the building to be built of stone, after Sultan Qalawun’s minaret. Prior to this, minarets were built of brick.

Both the minaret and the madrasa were built by the master Ibn al-Suyufi, head architect to the court of al-Nasir Muhammad.

Madrasa of al-Gawhariyya

Located in the far west of al-Azhar Mosque.

Amir Gawhar al-Qunquba’i al-Habashi, khaznadar (treasurer) to Sultan al-Ashraf Barsbay had the smallest of al-Azhar’s three madrasas built. The layout has a durqa‘a surrounded by four iwans. The durqa‘a is paved in coloured marble with a lantern ceiling above. Its doors are of wood with ebony and ivory inlay, while the windows are inlaid with coloured glass.

Turning left on entering al-Gawhariyya from the main al-Azhar Mosque is the mausoleum where its founder was buried in 844/1440. The outside of the dome is noted for a floral lattice design carved into the stone, its exquisite ornamentation is recognised as a milestone in the development of dome ornamentation in the Mamluk era.

M. M.

III.1.b Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri

This madrasa, also called a mosque, is located on al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street on the crossroads with al-Azhar Street. Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer)

Mukhtass the Eunuch, cupbearer to Sultan Qansuh Abi Sa‘id (r. 904/1498-905/1499), undertook the building of a mosque on the site of the present day madrasa. With Sultan al-Ghuri’s accession to the throne in 906/1501, he ordered Mukhtass’ arrest along with the confiscation of his wealth, and demanded a large sum of money in addition. Mukhtass, having no other source of money, gave up the land and the building with all that it contained as part of the sum demanded.

Sultan al-Ghuri ordered the buildings on the land to be destroyed and acquired neighbouring properties thus extending the plot. He had shops built on the ground floor to expand the commercial value of the site, which came to be known as al-Ghuriya. Al-Ghuri took particular care in his choice of marble to decorate the building, completed in 909/1503. The architect excelled himself in the ornamentation of the cruciform building, leaving not a single corner untouched. Not only the lintels, but the intrados, voussoirs and archways, too, were carefully sculpted with inscriptions and floral motifs.

Along the top of the façade on al-Mu‘izz li Din Allah Street, a Qur’anic inscription in naskhi script sings the praises of the Sultan: “man of the sword and the pen, of wisdom, of science … ”.

The madrasa is on the corner with al-Azhar Street. Its main entrance, on the corner of the building, is reached by a double staircase, one rising in al-Mu‘izz li Din Allah Street the other in al-Azhar Street. Its monumental entrance is crowned by a tri-lobed arch with several rows of muqarnas, an original geometric formation, and the Sultan’s circular emblem in the spandrels.

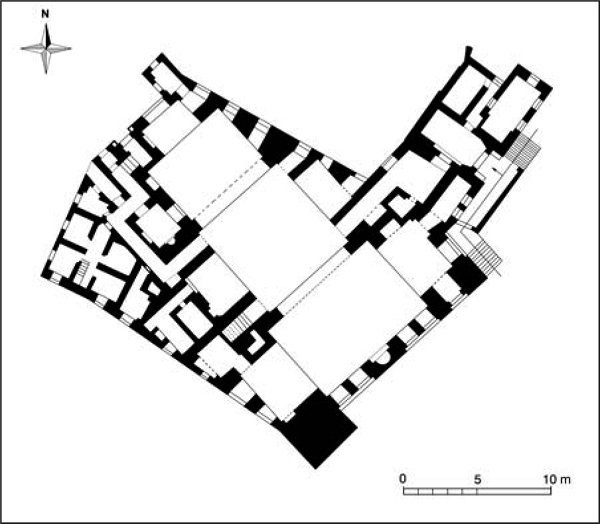

Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri, plan, Cairo.

Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri, partial view of the façade, Cairo.

A bent passageway with a muzammala leads from the entrance derka to the square inner courtyard, around the upper part of which are four rows of gilt wooden muqarnas. Up to a height of 2 m., the walls are panelled with vertical strips of coloured marble. A frieze bearing a floral Kufic inscription runs around the top of the panelling, written in a black paste inlaid in the white marble. The students received their classes in the four iwans located on the edge of the courtyard and lodged in rooms on the upper floors.

Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri, mihrab, detail of the arch, Cairo.

Madrasa of Sultan al-Ghuri, wooden minbar, detail, Cairo.

The qibla iwan is the largest of the four and opens onto the courtyard through a pointed horseshoe arch supported on jambs crowned with stone muqarnas in the form of capitals. The iwan is dominated by the finely ornamented marble mihrab crowned by a pointed arch resting on white marble columns. The minbar to the right of the mihrab is made of small interlocking pieces of wood forming geometric shapes inlaid with ivory and mother of pearl. The iwan opposite the qibla opens onto the courtyard through a pointed arch with its apex meeting the ceiling. It is noted for the wooden dikkat al-muballigh platform suspended half way up the span of the arch, which rests majestically on wooden brackets painted with inscriptions and gold floral motifs.

In the far south east corner of the madrasa the minaret base rises up from the top of the façade, which is crowned by a row of fleur-de-lys. The three sections of the minaret shaft are separated by wooden balconies, which are supported on delicate stone muqarnas. The original ceramic chequered decoration on the third section has now been replaced by painted ornamentation of a similar design. The unusual upper section was originally built of stone and had four “heads” crowned with bulbiform finials. Soon after its construction, the weight of this unique element proved too much and it started to lean to one side, the minaret threatening to collapse. Sultan al-Ghuri decided to reduce the heads from four to two, and they remained that way until the 12th/18th century when they were again replaced with five wooden finials as we see them today.

Sultan al-Ghuri was the last of the great patrons of architecture among the Mamluk Sultans in Egypt. His buildings reflect his will to improve certain urban areas, in particular in favour of education and science. The historian Ibn Iyas reveals his enthusiasm for the madrasa in the following sentiment: “this is a splendid building, of magnificent elegance … This madrasa is one of the wonders of our era”.

M. M.

III.1.c Complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun

The architectural complex of Sultan Qalawun is on al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street on the other side of al-Azhar Street, opposite the Muhib al-Din (Bayt al-Qadi).

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer). Mausoleum and hospital opening times are from 08.00 until sunset. The complex is currently undergoing restoration work and visitors are not allowed inside.

When serving Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari as an amir, Qalawun fell ill and was treated in the maristan (hospital) of al-Nuri in Damascus. So impressed and pleased was he by the hospital that he vowed to build a similar institution some day in Cairo, should God favour him by making him Sultan of Egypt. Soon after acceding to the throne in 678/1279, he bought the land and buildings from the owners of a plot of land, which had at one time partly belonged to the Fatimid West or Small Palace. He had the hospital built there as part of this large complex, which was also to include a madrasa and mausoleum.

Complex of Sultan Qalawun, main view, Cairo.

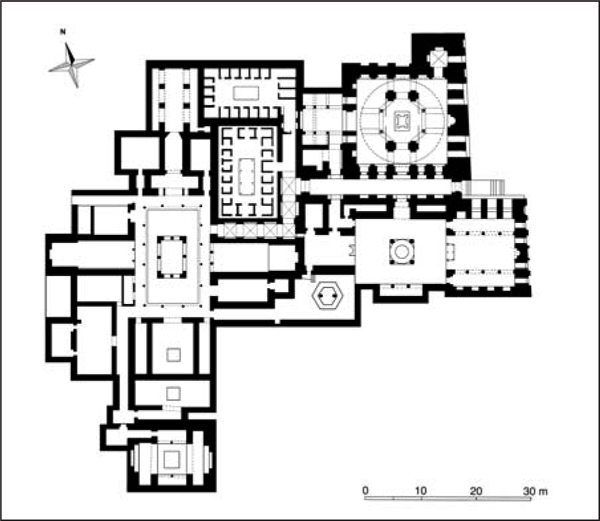

Complex of Sultan Qalawun, plan, Cairo.

Work began in 683/1284 and was completed in the uncommonly short period of time of a year and a month. The historian al-Maqrizi relates several anecdotes on the subject of its construction. He recounts how the man in charge of the building used to force passers-by to carry building materials into the complex. The news spread quickly through the city and soon people stopped going past the site.

Complex of Sultan Qalawun, mausoleum interior, Cairo.

This building complex is said to mark the beginning of a new style of construction for great architectural complexes. These comprised buildings of different sizes according to their uses – a model, which would soon become the predominant one in later Ottoman architecture.

The choice of location for this impressive construction on the western side of al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street was partly due to the need for the qibla, madrasa and qubba walls to coincide on the same street façade. The structural importance of this north-south artery since Fatimid times constituted another decisive factor in its location.

The architect provided access to the three buildings through a single doorway facilitating security of the building and from there into a long bent passageway measuring 5 m. in width. The entrance portal is formed of two superimposed arches over the door lintel, the first of which is slightly pointed while the second is a horseshoe arch. It is the first entrance portal of its kind in Mamluk architecture in Cairo.

The façade measures 67 m. in length along the street with subtle variations in design separating the mausoleum, to the right and set back some 10 m. from the street, from the madrasa to the left, which stands further forward. The architectural detail of the mausoleum indicates that this is where most care was taken with the housing of the tomb. At the end of the entrance passageway to the right, a domed derka leads to an open, arcaded courtyard. On passing through a wooden mashrabiyya screen crowned by one of the most impressive stucco ornaments still preserved intact, we reach the magnificent qubba of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun and his son al-Nasir Muhammad. The large dome rising above the mausoleum rests on an octagonal drum supported by four columns, and between them, four paired pillars – one of the elements most associated with Syrian influence. With its varied ornamentation, encrusted with mosaics, the mihrab is said to be one of the most splendid examples of Islamic architecture.

To the left of the passageway two entranceways lead to the madrasa – a central courtyard surrounded by four iwans. The sanctuary iwan is the largest of the four. The foundation documents stipulate that the students’ rooms should be located around the iwans, and the al-faqihs’ lodgings on the upper floor.

The southeast iwan has three aisles separated by arcades, perpendicular to the qibla wall, the widest aisle being the central one. Here the layout is clearly influenced by the Christian basilica model.

Little remains of the hospital located at the end of the passageway. Nevertheless, historical sources and archaeological excavations have revealed a considerable amount of information regarding its layout.

It continued to be used as a working hospital until the mid-13th/19th century, though today two large iwans are all that remain of the original building. The Ministry of Waqfs built a specialist eye hospital on the site of the rest of the building in 1915.

With the complex built over the remains of the Fatimid Western Palace, archaeological excavations have also uncovered fragments of wood on which musicians, dancers, fishing and hunting scenes were carved during the Fatimid era. These fragments were placed facing the walls, for such figural representations were considered blasphemous in that era. Nowadays, they can be seen in the Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo.

In addition, there is evidence to suggest that the layout of the building was a divided one with different sections for men and women in each of the care units of the hospital. This design resembles that of the al-Nuri Hospital in Damascus. The hospital had 100 beds available shared among the areas of surgery, fractures, intestinal disorders, ophthalmology, neurology, psychology, as well as out-patients, isolation for contagious diseases, a pharmacy, store rooms for instruments and other rooms for various other services.

In addition, medicine was taught in the hospital, which also had a library. The main hall, previously one of the halls of the Fatimid Palace, was used as an observation room and for post-operational intensive care.

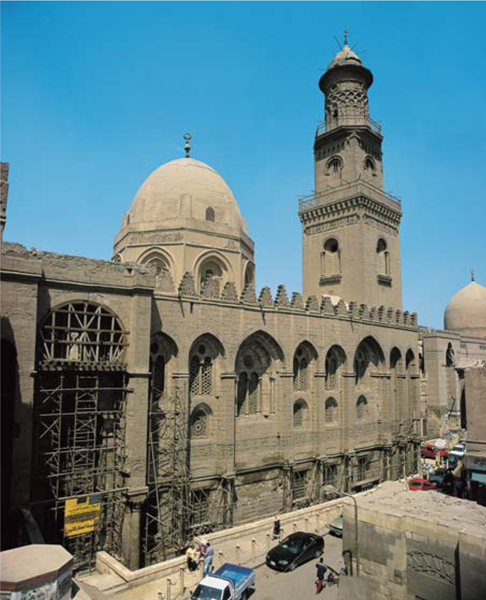

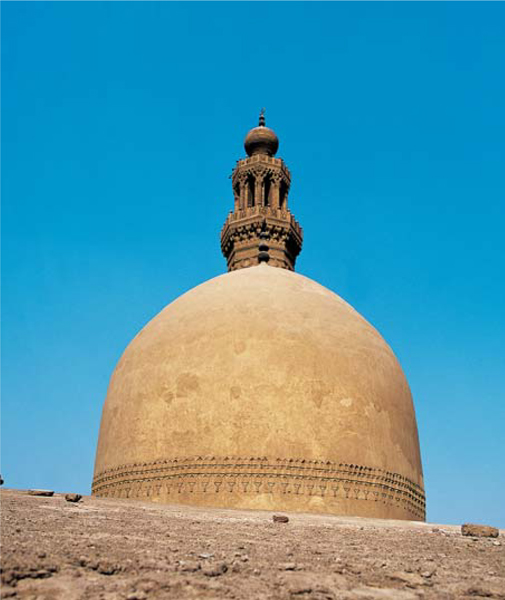

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, dome and minaret, Cairo.

The minaret on the eastern edge of mausoleum wall has three sections, which become successively narrower. The first two sections are square-based while the third is circular. This is the work of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, son of Qalawun, who commissioned its building in 703/1303 to replace an earlier minaret destroyed by an earthquake that year. The upper part of the first section bears an inscription commemorating this act and mentions the founder, his titles, and the date of its construction.

S. B.

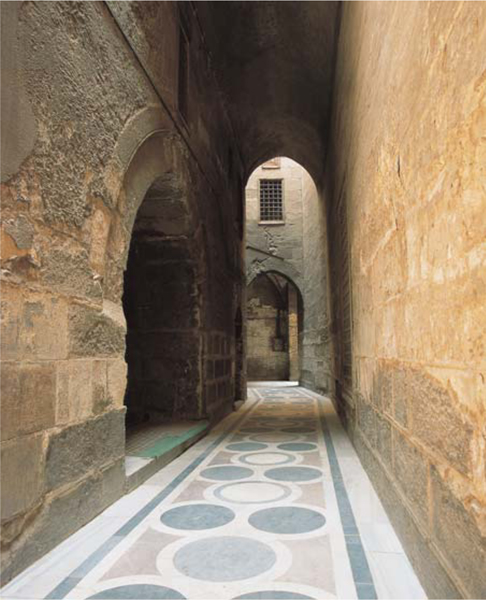

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, passageway between khanqa and derka, Cairo.

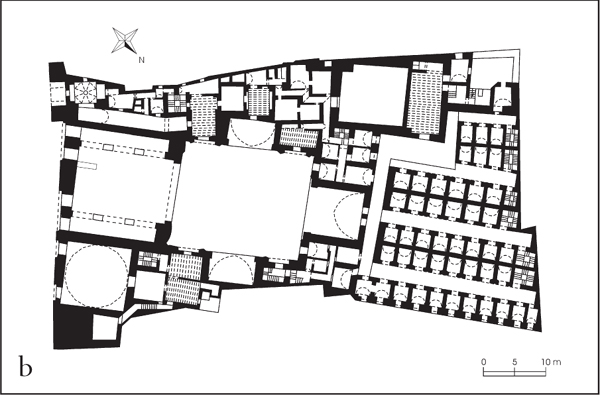

III.1.d Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq

The Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq are located on al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street next to the Sultan Qalawun Complex.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

Sultan Barquq, known by the name barquq (meaning plums) for his protruding eyes, acceded to the throne in the year 784/1382, the first Circassian Sultan of Egypt. Amir Jarkas al-Khalili supervised the building of the khanqa and madrasa, which took two years to complete between 786/1384 and 788/1386. The great master Shihab al-Din Ahmad Ibn Tulun was the chief architect, the son of a family with a long history in the profession, who were well known for several buildings in Egypt and the al-Hijaz. In the Mamluk era architects were held in great respect by sultans; Ahmad Ibn Tulun’s marriage to the sultan’s daughter reflects the respect bestowed upon him and his noted position in the courts.

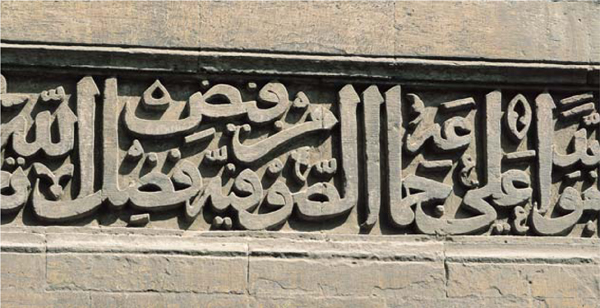

The main façade on the west side of al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street, similar to the Complex of Qalawun, stretches from the minaret in the north west to the monumental entrance in the south east. Most notable are the vertical recesses along the length of the façade, and the windows on street level covered by bronze grilles. The windows, crowned by marble lintels with their voussoirs interlocking, are in the ablaq technique. The upper part of the building has pointed arches framing the windows with their wooden mashrabiyya screens displaying perfect geometric shapes formed by small pieces of turned wood. The madrasa wall differs from the mausoleum wall in a few aspects, but its length is unified in the cresting across the top of the façade and the magnificent inscription carved in stone on a level with the third floor.

Despite the vast size of the minaret, it is well proportioned with its three octagonal sections. The uppermost section is open (gawsaq) and crowned with a bulbiform finial. The interlaced circles carved in stone and originally covered in marble make for remarkable ornamentation on the middle section. It is the only example of its kind ever built.

A double staircase ascends to the main entrance. The doors are faced in bronze with geometric motifs in relief, which combine with the inlaid floral motifs in silver to form a lattice. The name of Sultan Barquq can be read in the 18-pointed stars.

The red-and-white stone domed derka leads to the khanqa courtyard along a winding passageway open at each end and paved in coloured marble.

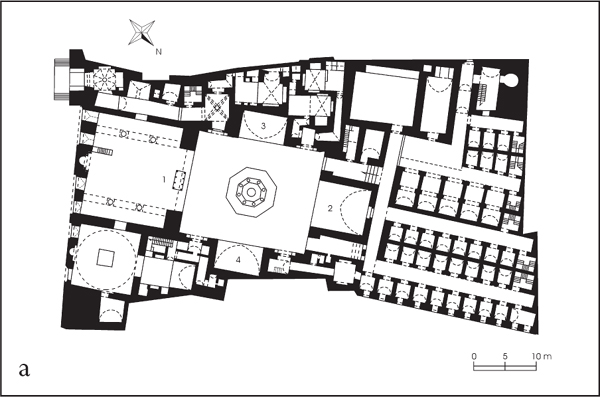

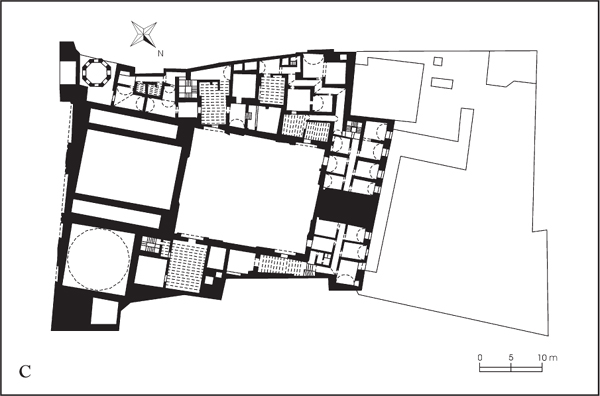

The layout of the building is the resulting blend of two styles; the cruciform madrasa with courtyard and four iwans, with the hypostyle mosque plan as we see in the south east iwan, divided into three aisles perpendicular to the qibla wall. The mihrab is flanked on either side by two niches high up on the wall with barred windows and decorated with coloured marble panelling and mother-of-pearl inlay. On one side is the wooden minbar, work of Sultan Jaqmaq (r. 842/1438-857/1453), and on the other the wooden Qur’an lectern, a masterpiece of craftsmanship inlaid with ivory. Across the entrance to the iwan is the marble dikkat al-muballigh supported on eight marble columns. The splendid ceiling decoration of this iwan displays a blue background with floral images and gilt inscriptions, contrasting with the remaining three iwans, covered by pointed barrel vaults. The north western and largest iwan was built using the mushahhar technique of alternating courses of coloured stone.

Khanqa and madrasa of Sultan Barquq, Cairo.

a. Ground floor:

1. Hanafi doctrine.

2. Shafi’i doctrine.

3. Maliki doctrine.

4. Hanbali doctrine.

b. First floor.

c. Second floor.

Classes on exegesis and Qur’anic recitation were taught in this khanqa along with hadith, the prophetic tradition, from the four legal rites. The qibla iwan was reserved for the hanafi doctrine, the rite followed by the Sultan, the north west for shafi‘i and the two side iwans for the maliki and hanbali doctrines.

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, mihrab and minbar, Cairo.

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Barquq, qibla iwan, detail of ceiling, Cairo.

The north west iwan has two passageways leading to the students and Sufis’ rooms, kitchen, water-well and ablutions hall. On the same side of the courtyard a door in the north west corner leads off to three rooms for the al-faqihs, (shafi’i, maliki and hanbali). In the opposite corner a door leads to stairs to the upper floors, where the hanafi faqih lived, and where there are more lodgings for the students as well as other rooms.

The mausoleum, in which the father and sons of the Sultan were buried, can be reached from the prayer hall. It is covered by a dome resting on pendentives of seven rows of gold muqarnas.

The centre of the courtyard is occupied by a fountain, its wooden dome supported on eight slender columns. In the south east corner of the courtyard a door leads off to several rooms on three different floors where the Sultan and his family lived during the various religious festivities. This residence, annexed to the khanqa, is in fact one of the building’s most unusual features.

M. M.

III.1.e Khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir

The khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir is located on al-Gamaliyya Street. Follow al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street towards Bab al-Futuh and turn right along Darb al-Asfar Street, which leads to the front of the monument.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

In 706/1306, two years before Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir acceded to the throne, building on the khanqa started on the site of the former Fatimid chancellery. It was officially opened in the Holy month of Ramadan 709/February 1310. Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir was, however, forced to give up the throne when al-Nasir Muhammad returned from Syria to rule for the third time. Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad promptly had Baybars al-Gashankir arrested and beheaded. On al-Nasir Muhammad’s orders the khanqa was closed and did not reopen until 18 years later 726/1326.

Khanqa and Madrasa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir, dome and minaret, Cairo.

The khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir is the oldest surviving example of its kind. As the waqf document states, this khanqa was destined to hold 400 Sufis, 100 of which were residents, and another 100 soldiers and sons of amirs. This document also provides us with information about “staff” provisions linked to this type of establishment. The staff consisted of two faqihs (one Hanafi and the other Shafi‘i) two reciters, a key keeper, one person in charge of maintenance, one in charge of damping down the building to keep it cool, another in charge of distributing water, a lamplighter, a cook, one person in charge of weights and measures, one to help with bread making, two helpers for making soup, an eye doctor and one to lay out the dead. There were additional employees for the residence and the tomb. Their salaries were paid with income from waqf properties, including lands in Egypt and al-Sham.

Khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir, entrance, Cairo.

Khanqa of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir, qubba mihrab, detail on panelling, Cairo.

The khanqa measures 68 m. in length and runs perpendicular to al-Gamaliyya Street; the façade is shared by the mausoleum and the main-entrance wall. The entrance is covered by a half vault of muqarnas and is crowned with a round arch, displaying an innovative development in architectural practices. Two niches have been added above the marble benches in the centre of the side wall. Round arches resting on marble columns built in the ablaq technique rise above them.

Half way up the façade, a band bearing a naskhi inscription runs the length of the building mentioning the khanqa as a waqf foundation for Sufis and specifying the full name of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir. The word “sultan” is missing, believed to have been removed by Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, (see the right hand side of the mausoleum wall).

The khanqa is a regular shaped building on an irregular plot of land. Its rectangular central courtyard is open and it has four iwans. The south east iwan is the largest and was reserved for the teaching of the shafi‘i doctrine. One of the most unusual aspects of this building is the inclusion of a mihrab in each of the side iwans. There are cells for the Sufis surrounding the stone-flagged courtyard.

The burial qubba is particularly noted for the unusual decoration of its mihrab, which comprises small alternating stone-and-shell paired colonettes in an arch formation with their spandrels decorated with leaf motifs in relief. On the opposite side bordering the street, there is a room in which special classes on the prophetic tradition (hadith) were taught.

The minaret above the main entrance has three sections (square-based, circular and gawsaq), each separated by a balcony supported on several rows of muqarnas. The minaret is crowned with a ribbed finial known as mabkhara for its incense burner shape, originally decorated with green ceramic tiles or faience.

M. M.

WAQF ORGANISATION IN THE MAMLUK ERA

Mohamed Abd El-Aziz

Waqf meaning to stop or to immobilise, also expresses in Islam the act of donating personal belongings as charitable endowments; devoutly bequeathing property to the needs of the religious community, humanitarian needs or for public service. A bequest or donation might constitute wealth in terms of lands or real estate, which once bequeathed, could not be sold, bought, possessed, inherited, given away or mortgaged. Its profits were destined to the upkeep of charitable works or actions in accordance with the conditions set out by the benefactor.

Like many other peoples, the Arabs already knew of the waqf system in its broader sense long before the birth of Islam. The Ka‘ba, al-Aqsa Mosque and churches on the tip of the Arabian Peninsula did not belong to any one person as private property, but rather were used by all followers of many different religions. The waqf is based on one of the religious principles set out by Islamic jurisprudence: compulsory almsgiving, proof of which is the Hadith (or prophetic tradition of Muhammad). According to Islamic law “when somebody dies his acts die with him, unless one of the three following circumstances occur, he leaves an ongoing charitable act, he leaves a teaching which is of benefit to mankind, or that he leaves a son who calls upon God in his name”.

The Arab conquest of Egypt heralded the arrival of the Islamic waqf system, the constitution of which was an act believed to bring man closer to God. From the beginning of the Islamic period Muslims adopted the custom of setting up waqf foundations, a tradition which was to proliferate in Egypt. Her oldest waqf was founded in agricultural lands in the first century of the hijra. Built in 68/687 during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Marwan, it was known as the waqf of the Garden of ‘Amr Ibn Mudarrak in Giza. Under Caliph Hisham Ibn ‘Abd al-Malik an institution was founded, considered to be the first of its kind both in Egypt and other Islamic countries, dedicated to the administration of these foundations and whose supervision was carried out by the Cadis, known as the “Ministry of Waqf”.

Khanga of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir, detail of the naskhi inscription mentioning the building as a waqf foundation, Cairo.

The Mamluk era was considered the Golden Age of the waqf system in Egypt. Cultural, social, political and economic factors all played a significant role in the spread and rise of the system, which was in turn influenced by the popularity of the very system that it promoted.

For those Mamluk Sultans who came to power by non-orthodox means, and were thus considered foreigners by native citizens of Egypt, the waqf system provided them with a method of gaining the acceptance of the local people and of promoting their government. Thus, many pious foundations were set up through donations such as land and real estate. Donations such as these were either from the donor’s own property or from public funds, to provide drinking water, education (primary schools), hospitals or other services such as the distribution of food to the poor or the laying out and burying of the dead.

It was due to the waqf system that the Mamluk Sultans and men of the State also achieved another objective – avoiding the confiscation of their property. It is worth remembering at this point that, with few exceptions, sultans did not rule by hereditary succession and that the newly invested sultan would frequently confiscate the belongings of his predecessor. Thus, through funds raised by waqf properties and independent of any changes that might occur in the future, the Mamluks guaranteed an income for themselves and for their descendants.

There were two types of waqfs: the first was a family endowment set up by the benefactor and which upon his death would be run by his descendants; and on their death, by a charitable foundation. The second was a charitable foundation, set up and run by a charitable institution. The Mamluk period saw the spread of a third type of waqf, a mix of the former two. In its founding deeds it clearly indicated that once the expenses of the charitable foundation had been paid, any surplus should go back to the founder and on his death to his descendants.

Among the economic factors that encouraged the Mamluk Sultans and the inhabitants of Egypt in general, to turn their property into charitable endowments was the fact that such properties were exempt of taxes and fees, for they were considered to belong to “dead” hands. Furthermore, on donating property to a pious foundation, they were freed of their legal obligations of almsgiving and the waqf system became in itself a means of almsgiving. Another reason for the increase in waqfs during the Mamluk era was the creation of an administrative foundation (diwan al-hashriyya) to deal with the property of those who died without descendants.

During the Mamluk era religious activity assumed unprecedented levels. Some of the motives for such activity are related to the origins of the sultans and amirs (slaves and not Arabs) and the education they received. Other reasons are connected with the general policy of strengthening the ties between the court, the state and religious institutions. These sultans founded many religious institutions, madrasas, khanqas and retreats, as well as mosques in order to strengthen religious unity and to help them put their varied pasts, origins and race behind them.

The pious foundation played an important role in maintaining mosques and in spreading the Faith. The institution made an enormous contribution to the spread of Sufism in Mamluk Egypt and part of the profits were invested in supporting Sufis who lived in isolation devoting themselves to prayer.

In addition many of the benefactors included a clause in the deeds of their foundation that part of the profits were to be invested in helping those who could not afford to carry out the religious duty of making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

The waqf, to a considerable extent, also supported the sultans’ ability to defend Islam and its lands. Citadels and forts were built on the borders to prevent attacks by Crusaders and to gather together the necessary troops, arms and equipment for their defence; hence the building of the Citadel of Qaytbay in Alexandria and the tower in Rosetta.

The increase in scientific activity in Egypt during the Mamluk period was directly related to the spread and consolidation of this system. The profits of such establishments were the principal source of income for the majority of madrasas and primary schools for orphans. As such, had it not been for such abundance of resources, scientific activity and the spread of religion during the Mamluk period would never have occurred.

The waqf system also provided a significant impulse to the development and great achievements attained by Egyptian Islamic Art, and promoted the conservation of ancient buildings, which have survived to our day. Masterpieces of Islamic Art as well as documents on the constitution of waqfs describing the buildings and their contents in minute detail have provided us with a wealth of artistic terms. Furthermore, the system guaranteed the future of the artisans and their skills, as well as the progressive development of different arts, for much of their income came from waqfs. Waqf foundations were generally the property of the rich and thus their conservation and the continuity of their use and enjoyment was guaranteed for both religious and civil foundations.