The Aging Population |

3 |

![]() Individuals aged 65 years can be expected to live an average of 18 more years than they did 100 years ago.

Individuals aged 65 years can be expected to live an average of 18 more years than they did 100 years ago.

![]() The average life span or the average expected age of older adults is 83 years.

The average life span or the average expected age of older adults is 83 years.

![]() Individuals aged 75 years can be expected to live an average of 11 more years, for a total of 86 years (http://www.health.gov/healthypeople).

Individuals aged 75 years can be expected to live an average of 11 more years, for a total of 86 years (http://www.health.gov/healthypeople).

![]() Older adults currently represent approximately 13% of the population. By the year 2030, they are expected to represent approximately 21% of the population.

Older adults currently represent approximately 13% of the population. By the year 2030, they are expected to represent approximately 21% of the population.

![]() The increase in the number of older adults in the United States is known as the graying of America.

The increase in the number of older adults in the United States is known as the graying of America.

![]() The graying of America brings about multiple issues and concerns for society:

The graying of America brings about multiple issues and concerns for society:

![]() How a majority of older adults will be viewed as members of society

How a majority of older adults will be viewed as members of society

![]() What resources will be available for older adults to live healthy and happy lives such as health care and housing

What resources will be available for older adults to live healthy and happy lives such as health care and housing

![]() The average older adult has three chronic medical illnesses that have the potential to

The average older adult has three chronic medical illnesses that have the potential to

![]() Reduce quality of life

Reduce quality of life

![]() Increase health care costs

Increase health care costs

Dividing older adults into segments allows nurses to recognize the unique differences present in each stage of older adulthood and provide more effective care.

![]() Adults aged 65 to 75 are the young-old.

Adults aged 65 to 75 are the young-old.

![]() Adults aged 75 to 85 are the old-old.

Adults aged 75 to 85 are the old-old.

![]() Those age 85 and older are the oldest old.

Those age 85 and older are the oldest old.

![]() Those who are 100 years and older are centenarians.

Those who are 100 years and older are centenarians.

![]() With the life span continuing to increase, will we need more categories in the future?

With the life span continuing to increase, will we need more categories in the future?

People are living longer for a number of reasons.

![]() Immunizations are available to prevent disease such as measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, and polio.

Immunizations are available to prevent disease such as measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, and polio.

![]() Annual influenza vaccination greatly decreases morbidity and mortality related to the flu and prevents complications of pneumonia.

Annual influenza vaccination greatly decreases morbidity and mortality related to the flu and prevents complications of pneumonia.

![]() Pneumonia vaccination is given to most older adults, especially high-risk patients—such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or splenectomies—and heart disease patients.

Pneumonia vaccination is given to most older adults, especially high-risk patients—such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or splenectomies—and heart disease patients.

![]() New diagnostic techniques assist in the early detection and treatment of disease.

New diagnostic techniques assist in the early detection and treatment of disease.

![]() Development of new medications to treat disease occurs daily.

Development of new medications to treat disease occurs daily.

![]() Improved economic conditions and nutrition.

Improved economic conditions and nutrition.

![]() Stronger emphasis on health promotion has undoubtedly resulted in decreases in both illness and death among the population.

Stronger emphasis on health promotion has undoubtedly resulted in decreases in both illness and death among the population.

Ageism is defined as a negative attitude or bias toward older adults, resulting in the belief that older people cannot or should not participate in societal activities or be given equal opportunities afforded to others. Ageism results in

![]() Lack of medical care of older adults

Lack of medical care of older adults

![]() Decreased access to services

Decreased access to services

![]() The potential for altered dignity and respect

The potential for altered dignity and respect

![]() Abandoned hopes of contributing to society

Abandoned hopes of contributing to society

![]() Policies and care decisions that are inequitable for older adults

Policies and care decisions that are inequitable for older adults

Older adults are combating ageism in a number of ways:

![]() Participating in large organizations that support older adults, such as AARP

Participating in large organizations that support older adults, such as AARP

![]() Demonstrating their continued and vast usefulness in society through volunteerism or grandparents’ raising grandchildren who would normally rely on state aid for support

Demonstrating their continued and vast usefulness in society through volunteerism or grandparents’ raising grandchildren who would normally rely on state aid for support

The foundation for ageism lies in the many myths of aging listed below:

Myth #1: Older adults are of little benefit to society.

![]() The rate of disability among older adults is steadily declining.

The rate of disability among older adults is steadily declining.

![]() Older adults are also mothers, fathers, grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, friends, and professionals such as teachers, physicians, nurses, and clergy.

Older adults are also mothers, fathers, grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, friends, and professionals such as teachers, physicians, nurses, and clergy.

![]() Older adults are of great benefit to those with whom they maintain relationships and serve in these roles.

Older adults are of great benefit to those with whom they maintain relationships and serve in these roles.

![]() Older adults are one of the nation’s greatest and most underutilized resources in that they make up a large volunteer pool that saves states and governments funds in unpaid services.

Older adults are one of the nation’s greatest and most underutilized resources in that they make up a large volunteer pool that saves states and governments funds in unpaid services.

![]() The number of older adults providing care to grandchildren continues to rise and supplies a significant amount of care that would normally fall on state government for support.

The number of older adults providing care to grandchildren continues to rise and supplies a significant amount of care that would normally fall on state government for support.

Myth #2: Older adults don’t pull their weight in society.

![]() Older adults who receive Social Security and Medicare paid into the system from which they are now drawing.

Older adults who receive Social Security and Medicare paid into the system from which they are now drawing.

![]() While many older adults retire, many others do not. In 2002, 13.2% of older Americans were working or were actively seeking work. A Gallup poll of 986 older adults reported that only 15% of older adults wished to retire, and the vast majority wanted to work as long as possible.

While many older adults retire, many others do not. In 2002, 13.2% of older Americans were working or were actively seeking work. A Gallup poll of 986 older adults reported that only 15% of older adults wished to retire, and the vast majority wanted to work as long as possible.

![]() Ageism in the workplace or sickness and disability may prevent older adults from working, although they may wish to.

Ageism in the workplace or sickness and disability may prevent older adults from working, although they may wish to.

![]() Older adults are also raising their grandchildren in record numbers because parents are

Older adults are also raising their grandchildren in record numbers because parents are

![]() Ill (related to HIV and other chronic illnesses)

Ill (related to HIV and other chronic illnesses)

![]() Abusive

Abusive

![]() Alcoholic or drug addicts

Alcoholic or drug addicts

![]() Incarcerated

Incarcerated

Myth #3: Older adults are cranky and disagreeable.

![]() The continuity theory supports that individuals move through their later years attempting to keep things much the same and using similar personality and coping strategies to maintain stability throughout life. Thus, cranky old people were probably cranky young people, too.

The continuity theory supports that individuals move through their later years attempting to keep things much the same and using similar personality and coping strategies to maintain stability throughout life. Thus, cranky old people were probably cranky young people, too.

![]() The average older adult has three chronic illnesses. Sickness—especially cognitive disorders—may alter an older adult’s personality.

The average older adult has three chronic illnesses. Sickness—especially cognitive disorders—may alter an older adult’s personality.

Myth #4: You can’t teach old dogs new tricks.

![]() Older adults are never too old to improve their nutritional level, start exercising, get a better night’s sleep, stop drinking and smoking, and improve their overall health and safety.

Older adults are never too old to improve their nutritional level, start exercising, get a better night’s sleep, stop drinking and smoking, and improve their overall health and safety.

![]() Older adults are increasingly returning to school and increasing their level of education. Many colleges and universities allow older adults to attend classes for low or no charge. In fact, 17% of older adults have a bachelor’s degree or more.

Older adults are increasingly returning to school and increasing their level of education. Many colleges and universities allow older adults to attend classes for low or no charge. In fact, 17% of older adults have a bachelor’s degree or more.

![]() Keeping intellectually active is regarded as a hallmark of successful aging.

Keeping intellectually active is regarded as a hallmark of successful aging.

Myth #5: Older adults are all senile.

![]() Memory losses are common in older adulthood, but are often falsely labeled as dementia.

Memory losses are common in older adulthood, but are often falsely labeled as dementia.

![]() The development of dementia is not a normal change of aging, but a pathological disease process evolving from neurological, vascular, infectious, metabolic, or degenerative processes or through trauma.

The development of dementia is not a normal change of aging, but a pathological disease process evolving from neurological, vascular, infectious, metabolic, or degenerative processes or through trauma.

![]() Dementia is a chronic loss of cognitive function that progresses over a long period of time.

Dementia is a chronic loss of cognitive function that progresses over a long period of time.

![]() Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older adults, making up about half of all dementia diagnoses.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older adults, making up about half of all dementia diagnoses.

![]() There are approximately 4.5 million U.S. residents with Alzheimer’s disease.

There are approximately 4.5 million U.S. residents with Alzheimer’s disease.

Myth #6: Depression is a normal response to the many losses older adults experience with aging.

![]() Recent research on depression indicates that there is more to the development of depression than the experience of loss.

Recent research on depression indicates that there is more to the development of depression than the experience of loss.

![]() The nature versus nurture controversy has uncovered the role of neurotransmitters in the development of depression among older adults.

The nature versus nurture controversy has uncovered the role of neurotransmitters in the development of depression among older adults.

![]() Because of the many physiological changes in aging of older adults, this population is more susceptible to the effects of altered neurotransmission than any other age group.

Because of the many physiological changes in aging of older adults, this population is more susceptible to the effects of altered neurotransmission than any other age group.

![]() Depression rates are highest among older adults with coexisting medical conditions.

Depression rates are highest among older adults with coexisting medical conditions.

Myth #7: Older adults are no longer interested in sex.

![]() Because sexuality is mainly considered a young person’s activity—often associated with reproduction—society doesn’t usually associate older adults with sex.

Because sexuality is mainly considered a young person’s activity—often associated with reproduction—society doesn’t usually associate older adults with sex.

![]() Recent surveys have shown that approximately 30% of older adults had participated in sexual activity over the past month.

Recent surveys have shown that approximately 30% of older adults had participated in sexual activity over the past month.

![]() Nurses and other health care providers do not assess sexuality, and few intervene to promote the sexuality of the older population.

Nurses and other health care providers do not assess sexuality, and few intervene to promote the sexuality of the older population.

![]() Reasons for nurses’ lack of attention to sexuality of older adults include lack of knowledge as well as general inexperience and discomfort.

Reasons for nurses’ lack of attention to sexuality of older adults include lack of knowledge as well as general inexperience and discomfort.

![]() Although it is true that some older adults have bad personal hygiene, this is definitely not applicable to the majority of the population.

Although it is true that some older adults have bad personal hygiene, this is definitely not applicable to the majority of the population.

![]() The numbers of odor-producing sweat glands diminishes as people age, leading to less perspiration among older adults.

The numbers of odor-producing sweat glands diminishes as people age, leading to less perspiration among older adults.

![]() Urinary and bowel incontinence—or the involuntary loss of urine and feces—occurs more commonly among older adults.

Urinary and bowel incontinence—or the involuntary loss of urine and feces—occurs more commonly among older adults.

![]() Both urinary and bowel incontinence are pathological changes of aging that result in loss of bladder or sphincter control and are highly treatable.

Both urinary and bowel incontinence are pathological changes of aging that result in loss of bladder or sphincter control and are highly treatable.

![]() Increased attention to older adults’ care will likely result in improved management of hygiene, incontinence, and associated disorders.

Increased attention to older adults’ care will likely result in improved management of hygiene, incontinence, and associated disorders.

Myth #9: The secret to successful aging is to choose your parents wisely.

![]() This phrase from the popular work of Rowe and Kahn (1998) on successful aging leads society to believe that little can be done to slow the aging process, because it is all set out in a nonmodifiable genetic plan dictated by lineage.

This phrase from the popular work of Rowe and Kahn (1998) on successful aging leads society to believe that little can be done to slow the aging process, because it is all set out in a nonmodifiable genetic plan dictated by lineage.

![]() While genetics are responsible for some parts of the aging process, they become less and less important as older adults age.

While genetics are responsible for some parts of the aging process, they become less and less important as older adults age.

![]() The role of environment and health behaviors significantly replaces the role of genetics in determining the onset of normal and pathological aging.

The role of environment and health behaviors significantly replaces the role of genetics in determining the onset of normal and pathological aging.

![]() Rowe and Kahn (1998) report that approximately one-third of physical aging and half of cognitive function is a result of genetic input from parental influences. That leaves two-thirds of physical aging and half of cognitive function to be influenced by environmental factors and health behaviors.

Rowe and Kahn (1998) report that approximately one-third of physical aging and half of cognitive function is a result of genetic input from parental influences. That leaves two-thirds of physical aging and half of cognitive function to be influenced by environmental factors and health behaviors.

![]() Many older adults, especially centenarians (those who have reached the age of 100), report that the key to successful aging is to enjoy and get satisfaction from life.

Many older adults, especially centenarians (those who have reached the age of 100), report that the key to successful aging is to enjoy and get satisfaction from life.

Myth #10: Because older adults are closer to death, they are ready to die and don’t require any special consideration at the end of life.

![]() This myth often leads health care professionals to offer less aggressive treatment for disease and to neglect essential components of end-of-life care for older adults.

This myth often leads health care professionals to offer less aggressive treatment for disease and to neglect essential components of end-of-life care for older adults.

![]() While death among older adults may occur after a long life, older adults are not necessarily ready for it.

While death among older adults may occur after a long life, older adults are not necessarily ready for it.

![]() The end of life is a difficult time for many older adults, but it also presents the opportunity to complete important developmental tasks of aging.

The end of life is a difficult time for many older adults, but it also presents the opportunity to complete important developmental tasks of aging.

![]() Nurses can play an important role in helping older adults to complete these developmental tasks that can make the difference between a good and a bad death.

Nurses can play an important role in helping older adults to complete these developmental tasks that can make the difference between a good and a bad death.

An unprecedented shift has taken place in the cultural backgrounds of the U.S. population, with the number of White older adults decreasing relative to increased numbers of Hispanic, African American, Asian, and other cultural groups.

![]() The United States currently functions under a health care system known popularly as the Western biomedical model.

The United States currently functions under a health care system known popularly as the Western biomedical model.

![]() This model forms the basis of beliefs about health care in the United States.

This model forms the basis of beliefs about health care in the United States.

![]() The model is based on scientific reductionism and is characterized by a mechanistic model of the human body, separation of mind and body, and disrespect of spirit or soul.

The model is based on scientific reductionism and is characterized by a mechanistic model of the human body, separation of mind and body, and disrespect of spirit or soul.

![]() Increased cultural diversity predicts a change in the manner in which traditional Western medicine is accepted in the United States and the need to understand other models of health and healing.

Increased cultural diversity predicts a change in the manner in which traditional Western medicine is accepted in the United States and the need to understand other models of health and healing.

![]() Thus, new interest is being shown in the dominant healing practices of other cultures, including:

Thus, new interest is being shown in the dominant healing practices of other cultures, including:

![]() Herbal medicine

Herbal medicine

![]() Acupuncture

Acupuncture

![]() Massage therapy

Massage therapy

![]() Biofeedback

Biofeedback

![]() Yoga

Yoga

![]() Tai chi

Tai chi

![]() Stress reduction

Stress reduction

![]() To fully understand how cultural shifts affect the way in which health care is accessed and accepted in society, it is first necessary to understand a few terms.

To fully understand how cultural shifts affect the way in which health care is accessed and accepted in society, it is first necessary to understand a few terms.

![]() Culture refers to the way of life of a population or part of a population. Culture also reflects differences in groups according to geographic regions or other characteristics that comprise subgroups within a nation.

Culture refers to the way of life of a population or part of a population. Culture also reflects differences in groups according to geographic regions or other characteristics that comprise subgroups within a nation.

![]() Acculturation is defined as the degree to which individuals have moved from their original system of cultural values and beliefs toward a new system.

Acculturation is defined as the degree to which individuals have moved from their original system of cultural values and beliefs toward a new system.

![]() Ethnogerontology is the study of the causes, processes, and consequences of race, national origin, culture, minority group status, and ethnic group status on individual and population aging in the three broad areas of biological, psychological, and social aging ( Jackson, 1985).

Ethnogerontology is the study of the causes, processes, and consequences of race, national origin, culture, minority group status, and ethnic group status on individual and population aging in the three broad areas of biological, psychological, and social aging ( Jackson, 1985).

Cultural competence is necessary for providing excellent nursing care for older adults of all cultural backgrounds. Purnell (2000) and Campinha-Bacote (2003) identify four stages of cultural competence.

![]() Unconscious incompetence is common to beginning nurses and is manifested by the assumption that everyone is the same.

Unconscious incompetence is common to beginning nurses and is manifested by the assumption that everyone is the same.

![]() Conscious incompetence occurs as the nurse begins to understand the vast differences between patients from many cultural backgrounds but lacks the knowledge to provide competent care to culturally diverse patient populations.

Conscious incompetence occurs as the nurse begins to understand the vast differences between patients from many cultural backgrounds but lacks the knowledge to provide competent care to culturally diverse patient populations.

![]() Conscious competence is the stage when knowledge regarding various cultures is actively obtained, but this knowledge is not easily integrated into practice, because the nurse is somewhat uncomfortable with culturally diverse interventions.

Conscious competence is the stage when knowledge regarding various cultures is actively obtained, but this knowledge is not easily integrated into practice, because the nurse is somewhat uncomfortable with culturally diverse interventions.

![]() Unconscious competence occurs when nurses naturally integrate knowledge and culturally appropriate interventions into practice (Campinha-Bacote, 2003).

Unconscious competence occurs when nurses naturally integrate knowledge and culturally appropriate interventions into practice (Campinha-Bacote, 2003).

The National Center for Cultural Competence was developed to increase the capacity of health care and mental health programs to design, implement, and evaluate culturally and linguistically competent services. The following steps are recommended:

![]() Examine personal beliefs and the impact of these beliefs on professional behavior.

Examine personal beliefs and the impact of these beliefs on professional behavior.

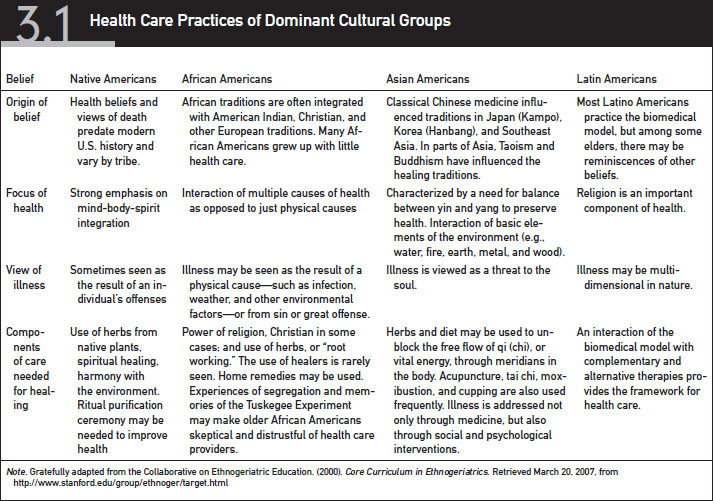

![]() Acquire knowledge regarding commonly encountered population-specific health-related cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors. These practices are listed in Table 3.1.

Acquire knowledge regarding commonly encountered population-specific health-related cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors. These practices are listed in Table 3.1.

![]() Aid in the development of culturally competent policies within the health care institution.

Aid in the development of culturally competent policies within the health care institution.

![]() Conduct competent cultural histories to determine the basis of the client’s health care beliefs and practices.

Conduct competent cultural histories to determine the basis of the client’s health care beliefs and practices.

![]() Remember to ask about the patient’s use of complementary and alternative therapy.

Remember to ask about the patient’s use of complementary and alternative therapy.

Theories of Nursing, Aging, Family, and Motivation

Nursing theory is comprised of a group of related concepts that guide practice. It is abstract (not measurable) and an essential component of professional knowledge base. Nursing theory contains four concepts:

![]() Person

Person

![]() Environment

Environment

![]() Nursing

Nursing

![]() Health

Health

Nursing grand theories are abstract, connect and relate the four main concepts of nursing, are not generally measurable, and are not usually used to guide research. Examples of nursing grand theories are:

![]() Nightingale (1859)—enhancing the body’s reparative processes by manipulation of noise, nutrition, hygiene, light, comfort, socialization, and hope.

Nightingale (1859)—enhancing the body’s reparative processes by manipulation of noise, nutrition, hygiene, light, comfort, socialization, and hope.

![]() Benner and Wrubel (1989)—caring as a means of coping with the stressors of illness; caring is central to the essence of nursing.

Benner and Wrubel (1989)—caring as a means of coping with the stressors of illness; caring is central to the essence of nursing.

![]() Orem (1971)—caring and helping clients to attain total self-care.

Orem (1971)—caring and helping clients to attain total self-care.

![]() King (1971)—communication to help clients reestablish positive adaptation to the environment. Supports that the nursing process is defined as a dynamic interpersonal process between the nurse, client, and health systems.

King (1971)—communication to help clients reestablish positive adaptation to the environment. Supports that the nursing process is defined as a dynamic interpersonal process between the nurse, client, and health systems.

![]() Watson (1979)—promoting health, restoring the client to health, and preventing illness.

Watson (1979)—promoting health, restoring the client to health, and preventing illness.

![]() Roy and Andrews (1999)—identifying types of demands placed on the client, assessing adaptation to demands, and helping clients adapt. The adaptation model is based on physiological, psychological, and sociological adaptive roles.

Roy and Andrews (1999)—identifying types of demands placed on the client, assessing adaptation to demands, and helping clients adapt. The adaptation model is based on physiological, psychological, and sociological adaptive roles.

![]() Neuman (1982)—assisting individuals, families, and groups in attaining and maintaining maximal level of total wellness by purposeful interventions. Stress reduction is the goal.

Neuman (1982)—assisting individuals, families, and groups in attaining and maintaining maximal level of total wellness by purposeful interventions. Stress reduction is the goal.

![]() Leininger (1991)—transcultural theory as a unifying domain for nursing knowledge and practice, providing care consistent with nursing’s emerging science and knowledge with caring as a central focus.

Leininger (1991)—transcultural theory as a unifying domain for nursing knowledge and practice, providing care consistent with nursing’s emerging science and knowledge with caring as a central focus.

![]() Henderson (1966)—focusing on the need to work independently with other health care workers assisting the client to gain independence as quickly as possible.

Henderson (1966)—focusing on the need to work independently with other health care workers assisting the client to gain independence as quickly as possible.

![]() Peplau (1952)—developing interaction between the nurse and client.

Peplau (1952)—developing interaction between the nurse and client.

![]() Rogers (1970)—maintaining and promoting health, preventing illness, and caring for and rehabilitating ill and disabled clients through the humanistic science of nursing to help people develop into unitary human beings.

Rogers (1970)—maintaining and promoting health, preventing illness, and caring for and rehabilitating ill and disabled clients through the humanistic science of nursing to help people develop into unitary human beings.

![]() Abdellah and colleagues (1960)—providing service to individuals, families, and society to be kind and caring but also intelligent, competent, and technically well prepared to provide this service; involves 21 nursing problems.

Abdellah and colleagues (1960)—providing service to individuals, families, and society to be kind and caring but also intelligent, competent, and technically well prepared to provide this service; involves 21 nursing problems.

Several categories of theories have been developed to describe why people age. Biological theories explain that the reason people age and die is because of changes in the human body (e.g., the Hayflick theory). Biological theories include

![]() DNA error

DNA error

![]() Accumulation of free radicals

Accumulation of free radicals

![]() Protein cross-linkage

Protein cross-linkage

![]() Wear and tear

Wear and tear

![]() Cell division time-out

Cell division time-out

![]() Immunity

Immunity

![]() Waste accumulation theory

Waste accumulation theory

Psychological theories support the idea that an older adult’s life ends when he or she has reached all of his or her developmental milestones. Psychological theories of aging include those of

![]() Maslow—self-actualization

Maslow—self-actualization

![]() Jung—self-realization

Jung—self-realization

![]() Erickson—integrity versus despair

Erickson—integrity versus despair

Moral/spiritual theories support the idea that once an older individual finds spiritual wholeness, this transcends the need to inhabit a body, and he or she dies. These theories include

![]() Tornstam’s theory of gerotranscendence

Tornstam’s theory of gerotranscendence

![]() Kohlberg’s theory of self-transcendence

Kohlberg’s theory of self-transcendence

Sociological theories explain that when an older adult’s usefulness in roles and relationships ends, death occurs.

![]() Disengagement theory explains that as relationships change or end for older adults, through the process of retirement, disability, or death, a gradual withdrawing of the older adult is evidenced. Less engagement in relationships and social activities is seen, and while new relationships may be formed, these relationships are not as integral to life as previously necessary.

Disengagement theory explains that as relationships change or end for older adults, through the process of retirement, disability, or death, a gradual withdrawing of the older adult is evidenced. Less engagement in relationships and social activities is seen, and while new relationships may be formed, these relationships are not as integral to life as previously necessary.

![]() Activity theory indicates that social activity is an essential component of successful aging. When social activity is halted because of death of loved ones, changes in relationship, or illness and disabilities that affect relationships, aging is accelerated and death becomes nearer.

Activity theory indicates that social activity is an essential component of successful aging. When social activity is halted because of death of loved ones, changes in relationship, or illness and disabilities that affect relationships, aging is accelerated and death becomes nearer.

![]() Continuity theory proposes that people age who most successfully carry forward the habits, preferences, lifestyles, and relationships from mid-life into later life and predicts strategies people will use to progress into old age.

Continuity theory proposes that people age who most successfully carry forward the habits, preferences, lifestyles, and relationships from mid-life into later life and predicts strategies people will use to progress into old age.

Family theory provides a framework for understanding human behavior and improving relationships in order to assist individuals, families, communities, and organizations work through major life issues. In older adulthood, major life transitions include

![]() Retirement

Retirement

![]() Relocation

Relocation

![]() Loss of spouse and other family members and friends

Loss of spouse and other family members and friends

![]() Financial constraints

Financial constraints

Effectively functioning families with good communication are critical to helping older adults make transitions smoothly and decreasing the risk of depression and other negative effects of stress. Poorly functioning family processes leave older adults at risk for ineffective coping. These families may benefit from family therapy as well as individual therapy.

![]() Key family theories include those of Freud and Bowen.

Key family theories include those of Freud and Bowen.

Motivational theory is generally associated with workplace employment and the desire to develop more effective employees.

![]() Herzberg’s hygienic needs theory focuses on the need to avoid discomfort and achieve personal fulfillment through maintaining good relationships, work conditions, salary, status, security, and a satisfying personal life.

Herzberg’s hygienic needs theory focuses on the need to avoid discomfort and achieve personal fulfillment through maintaining good relationships, work conditions, salary, status, security, and a satisfying personal life.

![]() McGregor’s X-Y theory focuses on whether people are lazy or ambitious.

McGregor’s X-Y theory focuses on whether people are lazy or ambitious.

![]() Adams’s equity theory focuses on patterns of fairness.

Adams’s equity theory focuses on patterns of fairness.

![]() McClelland’s motivational theory centers on motivational power.

McClelland’s motivational theory centers on motivational power.

In relation to older adults, motivational theory can be more specifically applied to changes in behaviors needed to improve health, for example:

![]() Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation

![]() Alcohol withdrawal and abstention

Alcohol withdrawal and abstention

![]() Nutritional changes

Nutritional changes

![]() Weight loss

Weight loss

![]() Exercise

Exercise

![]() Sleep hygiene

Sleep hygiene

Motivational theories support that it is critical to determine the motivational factor in order to change behavior. Thus, the determination of a critical end result and continuous feedback toward that result are important factors changing health behaviors among older adults. Researchers in motivational theory have identified the following potential motivators:

![]() Desire to avoid negative result of behavior

Desire to avoid negative result of behavior

![]() Achievement of a goal

Achievement of a goal

![]() Recognition of activity

Recognition of activity

![]() Health behavior itself

Health behavior itself

![]() Responsibility

Responsibility

![]() Advancement or progress

Advancement or progress

![]() Personal growth

Personal growth

Health promotion activities may be centered on these potential motivators to enhance compliance and success.

Communication with older adult clients is often complicated by many factors. Some factors that may result in a nursing diagnosis of impaired communication include

![]() Hard of hearing

Hard of hearing

![]() Dysphagia

Dysphagia

![]() Dementia

Dementia

In working with older adults, effective communication is essential and is the responsibility of the health care provider. Outcomes of successful communication include

![]() The client being able to communicate effectively with health care providers.

The client being able to communicate effectively with health care providers.

![]() The client utilizing alternative communication methods to convey his or her meaning.

The client utilizing alternative communication methods to convey his or her meaning.

![]() The client being able to correctly understand messages conveyed by health care providers.

The client being able to correctly understand messages conveyed by health care providers.

Interventions to aid in effective communication include

![]() Assessing the client’s receptive abilities—can the older adult understand what you are communicating?

Assessing the client’s receptive abilities—can the older adult understand what you are communicating?

![]() Assessing the client’s expressive abilities—can the older adult communicate his or her needs and desires?

Assessing the client’s expressive abilities—can the older adult communicate his or her needs and desires?

![]() Identifying the client’s sensory impairments that affect his or her communication, such as

Identifying the client’s sensory impairments that affect his or her communication, such as

![]() Hearing impairments

Hearing impairments

![]() Aphasias

Aphasias

![]() Visual impairments

Visual impairments

![]() Facing the client directly and speaking slowly, clearly, and concisely

Facing the client directly and speaking slowly, clearly, and concisely

![]() Demonstrating the skill or activity that you would like to communicate to the older adult

Demonstrating the skill or activity that you would like to communicate to the older adult

![]() Using interpreter services as necessary

Using interpreter services as necessary

![]() Using paper, pencil, or computer communication when necessary

Using paper, pencil, or computer communication when necessary

![]() Validating the client’s understanding of messages by asking him or her to repeat what was said

Validating the client’s understanding of messages by asking him or her to repeat what was said

![]() Being alert for nonverbal signs of behavior, especially in cognitively impaired older adults

Being alert for nonverbal signs of behavior, especially in cognitively impaired older adults

![]() Providing older adult with yes/no choices

Providing older adult with yes/no choices

![]() Providing easy instructions in short, simple sentences

Providing easy instructions in short, simple sentences

![]() Using physical cues and gesturing

Using physical cues and gesturing

![]() Limiting choices to reduce confusion

Limiting choices to reduce confusion

The Alzheimer’s Association (2008) recommends a number of assessment questions and communication tips, which are displayed in Table 3.2. Assessment of specific receptive and expressive abilities is needed in order to understand the patient’s communication difficulties and facilitate communication.

Teaching-Learning Theories and Principles

Teaching refers to transference of knowledge, and learning results from an educational experience aimed at improving knowledge and skills or changing behaviors. Behaviorist theories focus on immediate and consistent positive feedback of good behaviors implemented as a result of the teaching-learning process. Negative behaviors associated with the process are ignored. Practicing the right behavior repeatedly is critical.

Cognitive teaching-learning theories focus on an active learning approach aimed at developing human insight. Goal setting and attainment are the underlying principles of this teaching-learning process.

Constructivist theories surround an engaging process that combines both behaviorist and cognitive strategies to promote effective teaching and learning. The foundation for learning is built on students’ past experiences.

![]() Although many myths of aging lead health care providers to avoid teaching in this population, older adults are capable of gaining new knowledge and changing behaviors even at very advanced ages.

Although many myths of aging lead health care providers to avoid teaching in this population, older adults are capable of gaining new knowledge and changing behaviors even at very advanced ages.

![]() Older adults have many heterogeneous educational experiences and learning styles that require individualization of teaching strategies.

Older adults have many heterogeneous educational experiences and learning styles that require individualization of teaching strategies.

![]() Identifying an older adult’s learning style and individualizing one’s teaching methods accordingly is important for successful teaching and learning to take place.

Identifying an older adult’s learning style and individualizing one’s teaching methods accordingly is important for successful teaching and learning to take place.

![]() Health literacy is defined as the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services necessary to make appropriate health care decisions.

Health literacy is defined as the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services necessary to make appropriate health care decisions.

![]() Low health literacy occurs frequently in older adults, who also tend to be those most in need of health services. Health literacy requires that older adults not only be able to read information, but understand what they are reading, hear instructions, calculate medications, and communicate questions.

Low health literacy occurs frequently in older adults, who also tend to be those most in need of health services. Health literacy requires that older adults not only be able to read information, but understand what they are reading, hear instructions, calculate medications, and communicate questions.

![]() Low health literacy often impacts the ability of older adults to fully understand medication instructions and health interventions.

Low health literacy often impacts the ability of older adults to fully understand medication instructions and health interventions.

![]() Low health literacy disrupts a client’s ability to effectively prepare for diagnostic tests, make follow-up appointments, and maintain health.

Low health literacy disrupts a client’s ability to effectively prepare for diagnostic tests, make follow-up appointments, and maintain health.

![]() Health literacy is a significant factor in noncompliance with health care treatments and medications.

Health literacy is a significant factor in noncompliance with health care treatments and medications.

![]() Clear communication has the capacity to assist those with low health literacy to maintain health.

Clear communication has the capacity to assist those with low health literacy to maintain health.

With the increased population of older adults, there is a great need to increase the number of competent geriatric-educated nurses. Although nursing was the first profession to develop standards of gerontological care and provide a certification mechanism to ensure competence, gerontological nursing has been slow to gain recognition as a nursing specialty. While an increased number of nursing programs offer courses in geriatric nursing or integrate best geriatric nursing practices throughout programs, geriatric nursing is still not a popular specialty area among nursing students.

Some of the terms associated with nursing and the elderly are used interchangeably.

![]() Geriatric nursing refers to the nursing care of older people with health problems or those requiring tertiary care.

Geriatric nursing refers to the nursing care of older people with health problems or those requiring tertiary care.

![]() Gerontological nursing includes health promotion, education, and disease prevention (primary and secondary care).

Gerontological nursing includes health promotion, education, and disease prevention (primary and secondary care).

![]() Gerontic nursing, although not a commonly known term, encompasses both of these aspects of nursing care of older adults.

Gerontic nursing, although not a commonly known term, encompasses both of these aspects of nursing care of older adults.

The American Nurses Association first recognized geriatric nursing as a specialty in 1966. Standards to guide the practice of gerontological nursing were first published by the American Nurses Association in 1976 and later revised in 1987 and 1995. Several organizations specialize in geriatric nursing.

![]() The National Gerontological Nursing Organization was developed in 1984 to support the growth of knowledge related to gerontological nursing science.

The National Gerontological Nursing Organization was developed in 1984 to support the growth of knowledge related to gerontological nursing science.

![]() The Gerontological Society of America, the American Society of Aging, and the American Geriatrics Society are multidisciplinary organizations that support aging knowledge and research.

The Gerontological Society of America, the American Society of Aging, and the American Geriatrics Society are multidisciplinary organizations that support aging knowledge and research.

Abdellah, F. G., Beland, I. L., Martin, A., & Matheney, R. V. (1960). Patient-centered approaches to nursing. New York: Macmillan.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2008). Tips for better communication. Retrieved March 24, 2008, from http://www.alz.org/living_with_alzheimers_communication.asp

Benner, P., & Wrubel, J. (1989). The primacy of caring: Stress and coping in health and illness. Kent, OH: Addison-Wesley.

Campinha-Bacote, J. (2003). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services (3rd ed.). Cincinnati, OH: Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates Press.

Collaborative on Ethnogeriatric Education. (2000). Core curriculum in ethnogeriatrics. Retrieved March 20, 2007, from http://www.stanford.edu/group/ethnoger/target.html

Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. (2000). Try this: Best practices in nursing care to older adults. New York: Author. Retrieved March 20, 2008, from http://www.hartfordign.org

Henderson, V. (1966). The nature of nursing. New York: Macmillan.

Jackson, J. J. (1985). Race, national origin, ethnicity, and aging. In R. Binstock & E. Shanas (Eds.), Handbook of aging and social sciences (pp. 264–268). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

King, I. M. (1971). Toward a theory for nursing: General concepts of human behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Leininger, M. (1991). Transcultural nursing: The study and practice field. Imprint, 38(2), 55–66.

Neuman, B. (1982). The systems concept and nursing. In B. Neuman, The Neuman systems model: Application to nursing education and practice (pp. 3–7). Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Nightingale, F. (1859). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not [With an introduction by Barbara Stevens Barnum and commentaries by contemporary nursing leaders. 1992, Commemorative edition]. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.

Orem, D. E. (1971). Nursing: Concepts of practice. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Peplau, H. E. (1952). Interpersonal relations in nursing. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Purnell, L. (2000). A description of the Purnell model for cultural competence. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 11(1), 40–46.

Rogers, M. E. (1970). An introduction to the theoretical basis of nursing. Philadelphia: FA Davis.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1998). Aging. Aging, 10, 142–144.

Roy, C., & Andrews, H. (1999). The Roy adaptation model (2nd ed.). Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange.

Watson, J. (l979). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.