CHAPTER Three

How Trauma Affects Young Children’s Brains and Their Ability to Learn

The child behaviors that challenge and puzzle educators are often the only tools a child has for processing adverse experiences. The behaviors also indicate what is happening in the brain. While a discussion of such a complex topic as brain development is beyond the scope of this book, understanding basic ways trauma can affect a child’s brain can help you as you partner with families and others to find the most effective ways to support children’s healthy growth and development.

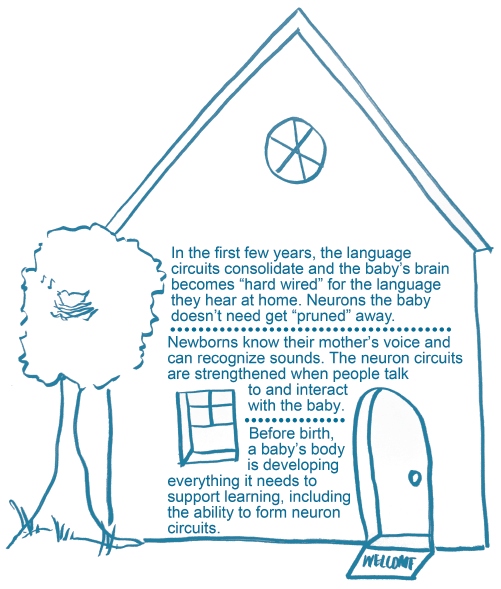

Figure 1. Just like a house, brain functions are built level by level.

Brain Circuits and Connections

Brain development is not a straightforward march along a set pathway. It is an interactive process in which genes provide a blueprint and experiences customize the brain to function in its particular environment (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. b; Sorrels 2015).

Neuronal connections, or circuits, build over time from simple connections into more complex interactions. In the first few years of life, “more than 1 million new neuronal connections form every second” (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. b). There is a reason the process of brain development is known as “brain architecture” (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. b): the process is similar to building a house, and it starts with a strong foundation (see Fig. 1).

Neuronal connections are either strengthened by repeated use or discarded if they are not needed. The process of discarding underused neuronal connections is called pruning and represents the brain fine-tuning the connections to be as adaptable as possible in response to environmental stimuli. A flexible brain can better take in and process information and adjust to thrive within the environment (Rotshtein & Mitchell 2018).

Experience and Brain Connections

A child’s early experiences—such as sensory input and the ability to explore and interact with the world—play a huge role in determining which connections are strengthened and which are pruned (Rotshtein & Mitchell 2018). For example, if a child is not exposed to rich and varied vocabulary or allowed to actively explore the environment, some of the neuronal networks needed for cognitive or academic learning may be pruned away (Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019). In the first few years of life, the brain is creating the foundation for all future learning, including social, emotional, and communication skills, by building strong neuronal connections that allow the brain to take in and use information and build on existing patterns and knowledge. Having a healthy, supportive environment is critical to this process since it allows the brain to physically develop.

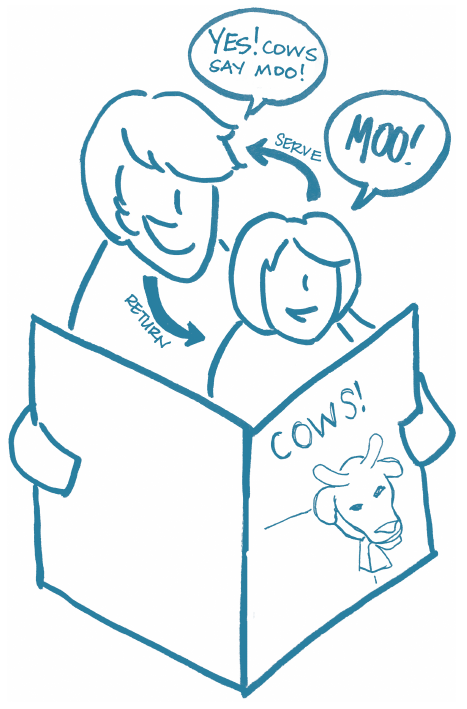

For example, one way neuronal connections are strengthened is through serve-and-return interactions between a child and another individual (see Fig. 2). These occur when an infant or young child babbles, gestures, cries, or otherwise engages with people and objects around them and an older child or adult responds through eye contact, words, physical contact like hugs, or other responsive actions. At the brain level, this back-and-forth strengthens the neuronal connections; at the behavioral level, the interaction builds crucial communication and social skills (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. d). Without this environmental feedback, young children may not develop these skills, because the neuronal connections aren’t strengthened and may eventually be pruned if they are underused. This means there is not as robust a foundation for developing future skills.

Figure 2. A serve-and-return interaction.

Responding to Stress

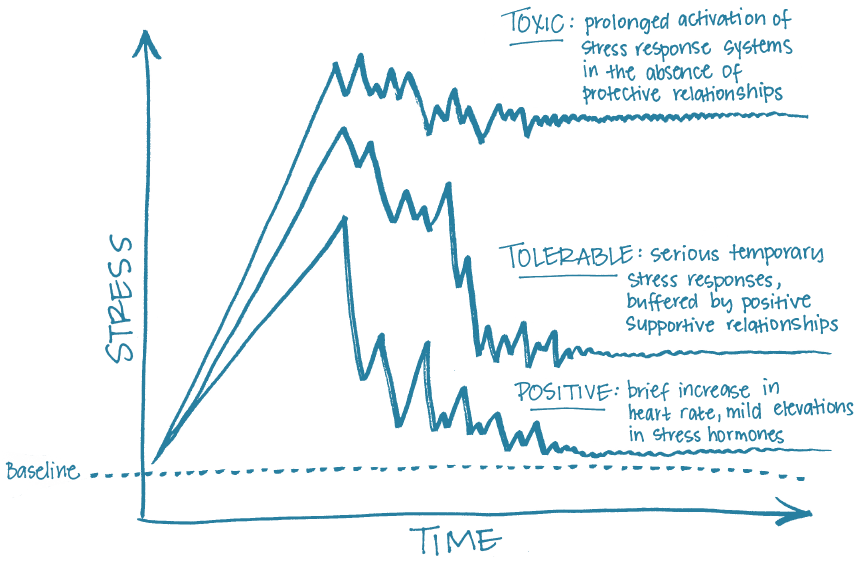

Adults not only help shape a child’s brain development through the interactions and experiences they provide, they also play an important role in helping children learn how to react and deal with difficult situations and develop a healthy stress response. Normal stress responses are brief, allowing the body to return to its natural state or baseline. For example, a child who is momentarily startled or frightened by someone saying “boo” may experience an increase in heart rate and breathe more rapidly. For most children that will last for only a few moments, and then they will return to their usual state of regulation.

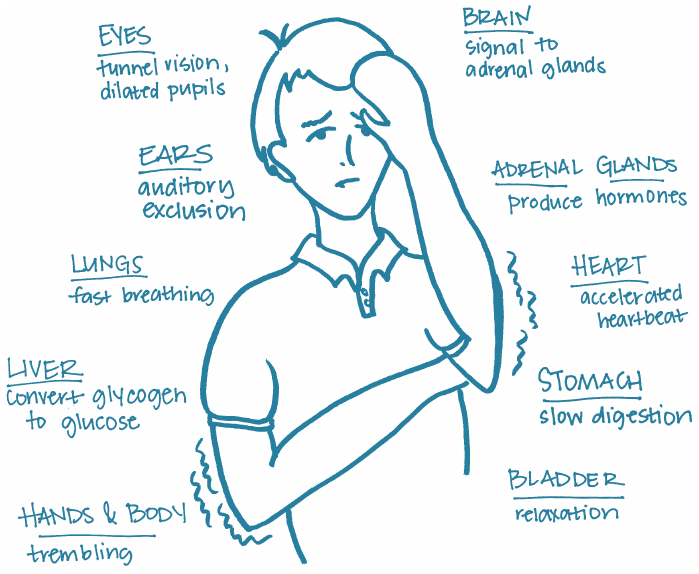

Figure 3. The body’s reactions to stress.

States of prolonged stress in children may occur after more severe traumas, like threat of physical or emotional harm, a severe injury, or the death of a loved one. At these times, a child’s body reacts by increasing the heart rate and blood pressure and releasing stress hormones (see Fig. 3). The longer the impact of the trauma, the longer these reactions last (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. e).

Learning to cope with these physiological changes in a healthy way is critical for children so they gain the skills they need to respond to stress or discomfort and can adapt and remain in control of their reaction. Children develop these skills by having caring adults model healthy reactions to stress and provide safe spaces where children can practice these skills. For example, you might encourage a child who is feeling angry to pound playdough, do some jumping jacks, or punch a pillow. Help the child find what works for them. When you teach a child how to deal with the stress in healthy ways, and the underlying conflict is resolved, the child’s body can adapt and return to its baseline state. Strategies for helping children regulate their emotional state are detailed in Chapter 4.

If trauma is complex or repeated, like physical or emotional abuse, and if supportive adults aren’t consistently present to help the child due to factors like neglect, family separation, mental illness, or substance use, a child’s body can experience a sustained stress response, known as toxic stress. In response, the brain sends signals for the body to take action in one of these ways: fight, flight, or freeze (Texas Children’s Hospital 2019). Instead of focusing on building healthy, strong neuronal connections—including those relating to the development of higher-order thinking skills—the brain puts its energy into a protective response (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. b). Figure 4, on the next page, illustrates the difference between the types of stress response.

Figure 4. Types of stress response.

The Impact of Trauma on Development and Learning

If toxic stress is not alleviated or a child does not receive treatment, the child is at risk for developmental and learning deficits now and for problems in learning, behavior, physical health, and mental well-being into their adulthood (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. e).

Early trauma may lead to documented social and emotional difficulties, such as feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, low self-concept, poor social skills, anxiety, depression, and pessimism. Physically, trauma may interfere with present growth and development and predispose children to lifelong health challenges.

“Effects of Trauma on Development,” lists possible developmental and learning consequences of toxic stress on young children’s cognitive, language, social and emotional, and physical abilities.

What Toxic Stress Looks Like in Early Childhood Programs

In an effort to escape danger and return to a pretrauma safe state, the brain triggers a fight (confront the threat), flight (run away), or freeze (shut down) response. The children in your program may display symptoms of trauma that reflect any of these responses. Though these symptoms may look like intentional misbehavior, they are children’s biological responses to the traumas they have endured.

The following behaviors are common signs of toxic stress in very young children (Children’s Bureau 2016; Government of Western Australia, n.d.; NCTSN 2008b; Nemeth & Brillante 2011; Sorrels 2015). Keep in mind that children may exhibit some of these signs, to a lesser degree or over a shorter time period, for reasons other than trauma.

Effects of Trauma on Development

Area of Development or Learning |

Consequences of Trauma |

Cognition and academic learning |

Can prevent a child from focusing attention, sequencing thought, and solving problems. Diminishes confidence and can affect ability to enter and sustain dramatic play scenarios. |

Language and communication |

Affects development of vocabulary, processing of language, communication, self-talk, and conversational skills. |

Social and emotional development |

Interferes with development of social skills, including respecting boundaries, not being able to take others’ perspective into account, and resolving conflict. Can also disrupt the sense of trust and security or cause a child to be in a constant state of fear or anxiety. |

Physical development |

Can lead to delays or stunted gross motor and fine motor development and negatively affect body awareness and muscle tone. |

Fight Behaviors

❯ Self-harm, such as biting oneself, pulling one’s hair, banging one’s head: Three-year-old Colton gets easily upset when there are changes in the program’s routine. When there is a substitute teacher, he goes to a corner of the room and starts hitting his head against the wall. He refuses to be soothed or calmed by the new teacher.

❯ Inconsolable or rage-filled crying and tantrums: When 4-year-old Antonio’s friend John tells him he doesn’t want to play with him, Antonio starts crying and yelling at John that he hates him. Antonio’s crying intensifies and lasts for the rest of free play, despite other friends and his teachers trying to redirect his attention.

❯ Inability to be soothed or calmed down: When the building Merry is working on in the block corner falls, she collapses into a heap on the floor and sobs. Her teacher, Ms. Cunningham, hugs Merry, who continues sobbing in her arms for a long time.

❯ Hitting, biting, and other aggressive behavior: When 3-year-old Shana’s friend Paul asks to use the easel she is painting at, Shana hits Paul and shoves the easel toward him, knocking him over.

❯ Verbal abuse of others: When Lamar joins 6-year-old David outside during kindergarten recess, David turns to him and yells, “Get off. I’m playing here, Stupidface. I didn’t tell you you could be here!” Every time Lamar tries to play in the area, David continues yelling at him and calling him names. When a teacher intervenes, David says, “He’s dumb and ugly. He can’t play with me.” This behavior continues for several recess times.

❯ Rude or defiant behavior: When 4-year-old Nathan’s teacher announces that it’s time to clean up while he’s still building with blocks, Nathan announces, “You can’t tell me what to do. You’re not the boss of me.” He continues to build with the blocks despite several verbal warnings. When the teacher comes over to intervene, Nathan kicks the blocks toward her and runs out of the room.

❯ Need for more control: Four-year-old Julian is operating the mouse while sitting at the computer working on a drawing program with Seseko. Seseko asks Julian to use a coloring option to change the background. Without looking at Seseko, Julian grits his teeth and announces, “No. I’m in charge. I have the mouse, so I can do what I want.” When Seseko protests, Julian shoves her aside and announces, “I’m the boss. I can do whatever I want. You need to listen to me.”

❯ Inappropriate sexual behavior or play: While playing in the dramatic play center, 4-year-old Ramon picks up a girl doll and a boy doll. He then puts the boy doll on top of the girl doll and moves the boy doll up and down over the girl doll while laughing.

Flight Behaviors

❯ Separation anxiety from family or program at arrival or departure: Four-year-old Eduardo cries every morning when his mom drops him off at school, even after being in pre-K for several months.

❯ Regression in skills previously mastered: When 3-year-old James arrives at his program, he turns to his teacher for help taking off his jacket and gloves, activities he was able to do until last week.

❯ Loss of bladder control (enuresis): Five-year-old Samanda has started wetting her pants for the first time all year.

❯ Physical complaints that seem unrelated to illness or accident: Five-year-old Keisha tells her teacher that she has a stomachache nearly every day before going home.

❯ Significant changes in eating patterns: Four-year-old Dougie sits at the table with everyone in his family child care program for lunch, but for the last few days he has refused to take a bite of any of the foods being served.

❯ Significant changes in sleep patterns: Three-year-old Liam lies down on his mat at rest time, gets up to get a toy, lies down again, says he forgot to brush his teeth even though he already brushed them, lies down again, gets up to drink water, and then goes and sits at a table.

❯ Worries about their own or another’s safety: Five-year-old Brandy tells her teacher about the drawing she just completed: “The mommy is staying home with her little girl. If she leaves the house, something bad will happen to the little girl.”

❯ Heightened vigilance and inaccurate perception of danger: Six-year-old Cecily hears a loud car exhaust sound and runs to take cover.

❯ Increased fearfulness: Three-year-old Montana wakes up from her nap crying and tells her teacher, “There was a monster in the room who was going to eat me.”

❯ Mood swings and personality changes: While marching with instruments outside, 4-year-old Marcus happily shakes maracas to the music. Then, without instigation, Marcus throws the maracas on the ground and starts complaining the activity is dumb.

❯ Repetitive play that re-creates traumatic events and is unproductive, not providing relief or further upsetting the child: Following a recent tornado, 4-year-old Giacinta builds a barn out of blocks. Then with a whooshing sound she yells, “Take cover!” and knocks her construction down with one swoop of her arm. She repeats this play over and over throughout the morning, bringing in small dolls and having the “mommy” doll pick up the “baby” doll and run away.

❯ Expressing worry that the trauma will recur: During morning meeting on the anniversary of the date his mother was severely injured in a car crash, 5-year-old Yahir announces that no one should get in a car today.

❯ Negative thinking in worst-case scenarios: When his teacher suggests that 6-year-old Dev join his friends in play on the outdoor equipment, Dev mutters, “They don’t want to play with me. They hate me. No one likes me.”

❯ Frequent talk about death and dying: While putting on a puppet show with two friends, 3-year-old Brooklyn suggests that the frog puppets go to the funeral for their babysitter who died. When one of the children suggests the puppets go to the movies instead, Brooklyn insists that funerals are more important. No matter what play scenarios the other children begin, Brooklyn always turns it toward a funeral.

Freeze Behaviors

❯ Muteness, refusal to talk: Every day at morning meeting, Ms. Sanchez goes around the circle and has everyone tell the group one thing they would like to do today. Whenever it’s Marta’s turn, she says nothing. Ms. Sanchez encourages Marta to say something, but Marta sits silently, staring at her teacher with her mouth clenched.

❯ Limited eye contact: When her favorite school bus driver greets her, 6-year-old Keine bows her head and refuses to look him in the eye and give him a big smile as she typically does.

❯ Withdrawal from activities: Five-year-old Emma sits quietly at the morning meeting with her hands in her lap. She stares blankly out the window and doesn’t move her head or eyes when the teacher asks for a volunteer to feed the classroom fish.

❯ Difficulty forming friendships: Before going on a nature walk, Mr. Lopez asks the class to find a partner to hold hands with on the walk. As the children pair up, 5-year-old Carmelo just stands there, not making eye contact with anyone. Seeing Carmelo standing alone, Mr. Lopez asks Emmit to be Carmelo’s partner. Emmit goes over to Carmelo and extends his hand. Carmelo just stands there as Emmit grabs his hand.

❯ Ignoring directions, not listening, or refusing to participate in activities: While baking bread in a small group, the teacher asks 4-year-old Emilia to proof the yeast by putting it in the bowl of water and sugar on the counter. Emilia takes the package and empties it on the counter. The teacher corrects her, telling her that she needs to clean up the poured yeast and then put another packet in the water. Emilia looks at her teacher and walks away from the cooking center.

❯ Quick to give up or unwilling to try new things: Five-year-old Curtis is working on a puzzle at a table. He puts one piece in and picks up a second piece. He tries it in one spot, but it doesn’t fit. He pushes the puzzle away and retreats to the library area.

❯ Over- or under-reacting to physical touch: When it’s time to go outside to play, a parent volunteer sees 6-year-old Zara struggling to put on her jacket. The parent walks over to Zara, reaches toward her, and says, “Here, Zara, I can help you.” Zara instantly recoils and moves out of reach.

❯ Overreacting to sounds or textures: While having family-style lunch, Ms. Cella passes the food around the table. She encourages 4-year-old Trinity to try some ramen. Trinity reluctantly puts a forkful in her mouth and immediately spits it out: “It’s too wiggly and slimy. It feels yucky in my mouth.”

❯ Overly dependent on others: Four-year-old Carola often insists that her teacher help her with tasks that she could easily do herself. When a parent volunteer attempts to get out her cot for rest time, Carola snaps at her, “I want Ms. Knight to help me. She knows how to do it.”

❯ Lack of self-confidence: While playing outdoors, Mr. Louis asks 6-year-old Connor to catch the ball with him. Connor softly replies, “I can’t do it. I can’t do anything.”

Some children exposed to toxic stress will exhibit just one or two signs while others will show multiple symptoms. It is important to remember that you are not responsible for confirming whether a child is dealing with toxic stress or providing any sort of diagnosis. These signs and examples can help you recognize that sometimes behaviors are a result of trauma, not a child’s intentional misbehavior or temporary circumstances. If you see these types of challenging behaviors, you can begin to help the child regulate their emotions using the strategies presented in Chapters 4–7.

A Path Forward

Understanding how children’s brain development and trauma are related and being able to identify what sort of physical, emotional, and social cues a child may exhibit if they are having a traumatic response will focus your efforts on helping the child in the moment. In addition, knowing some basics about brain development and the influence of early experiences will give you the tools to help others, such as family members, administrators, or lawmakers, understand the critical importance of TIC. The next few chapters will give you specific strategies to incorporate into your program to support children and families.