7

The Athanasian Creed

A Creedal Anomaly with Staying Power

In a collection of sermons by early sixth-century bishop Caesarius of Arles (in Gaul), there is a preface that reads in part, “And because it is necessary, and incumbent on them, that all clergymen, and laymen too, should be familiar with the Catholic faith, we have first of all written out in this collection the Catholic faith itself as the holy fathers defined it, for we ought both ourselves frequently to read it and to instruct others in it.” Following the preface is the full text of what we now call the Athanasian Creed, with the title “The Catholic Faith of Saint Athanasius the Bishop.”1

We should note straightaway that in this reference (recorded history’s first direct mention of the document), the Athanasian Creed is not called a creed. It is a document allegedly representing Athanasius’s “faith,” one that was meant for study by clergy and laity, not for liturgical recitation per se. It was not called a symbol until the thirteenth century; before that time it was dubbed “The Faith of Athanasius” or “The Catholic Faith.” Furthermore, the Athanasian Creed differs from others we have encountered in that it emerged neither through baptismal usage nor through conciliar deliberations. In both respects, the document scarcely seems to warrant its later categorization as a creed. And as we have already seen in chapter 1, it was not written by Athanasius. In fact, a well-known saying among creedal scholars is that there are only two things about the Athanasian Creed that are certain: it is not Athanasian, and it is not a creed. Thus, in this chapter we call the document “The Catholic Faith”2 as well as the “Athanasian Creed.” It is ironic that a document never meant as a creed, and not regarded as such until some seven hundred years after its composition, is revered as a creed today not only by Roman Catholics but also by those Protestants who affirm creeds. As we will see later in this book, most Protestant confessions that mentioned creeds included this as one of the creeds they affirmed.

What, then, is the story behind this odd document? How did it originate, and how did it take its place alongside the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds? These are the questions that we take up in this chapter.

Dispensing with the Attribution to Athanasius

As we consider the origins of “The Catholic Faith,” we should begin by justifying the now-universal belief that it was not written by Athanasius. First of all, it was written in Latin rather than Greek, and, in fact, it was not translated into Greek until at least the late twelfth century. Furthermore, there is no evidence that either Athanasius or any of his many Greek followers knew of it. The Byzantine world seems to have been largely unaware of it until the twelfth century. Third, the document’s theological terminology clearly presupposes a Western, Latin milieu and dates from a time later than Athanasius. As we have seen, the language for person and substance was still in flux in Athanasius’s time but was set by the time of this document, and as we will see later in this chapter, the document represents a later Western development in the way theology was conceptualized. Finally, the document affirms what theologians call the “double procession of the Holy Spirit”; that is, it claims that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, whereas the Nicene Creed had stated simply that he proceeds from the Father. This, too, is a Western development (if not actually subsequent to the time of Athanasius). From all of these considerations, it is clear that the document was written in a Latin theological milieu later than the end of the fourth century, and thus that its author could not have been Athanasius.3

Nevertheless, in the West, where it originated, “The Catholic Faith” was associated with Athanasius’s name and benefited enormously from his prestige. As part of the Carolingian effort to improve education, Charlemagne sought to impress on the clergy not only the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer but also “The Catholic Faith of St. Athanasius.” After the split between East and West (which we will discuss in chap. 10), the Western church began to insist that the East give attention to the Athanasian Creed. By the late fourteenth century, the West had been so successful in this endeavor that the Easterners concluded that the document was by Athanasius, although they insisted that the double procession of the Holy Spirit was a Western interpolation. But when modern Western scholarship began to question Athanasian authorship in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Eastern Orthodox Church decisively rejected the document.4 Thus, we see that the Athanasian attribution emerged in the West (as did the document itself) and was foisted on the East with only temporary success. In spite of the name, the Athanasian Creed is a Western document through and through. Athanasius himself had nothing to do with it.

The Composition and Early Use of “The Catholic Faith”

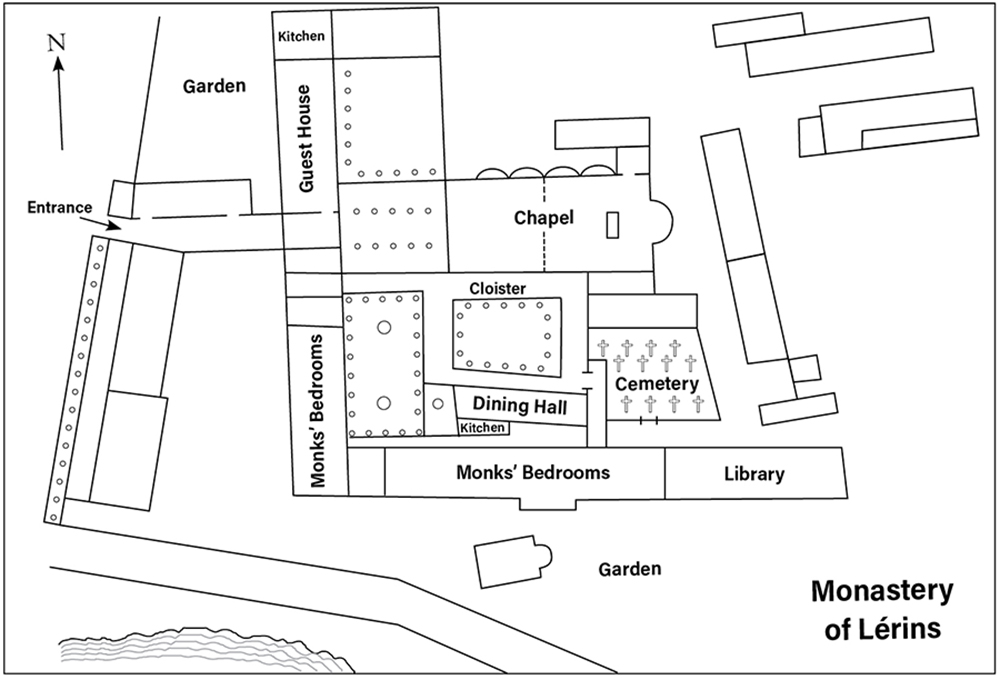

Where and when, then, did the document originate? It seems certain that Gaul was the place of writing, just as it was the place where Caesarius first quoted the document. There have been many scholarly attempts to pinpoint the location more precisely by comparing the document’s Latin style to that of Gallic writers, and to pinpoint the date by locating the theological language of the document within the flow of the trinitarian and christological controversies. These inquiries, over more than two hundred years of scholarly work, have led to a general conclusion that “The Catholic Faith” came from the orbit of the monastery at Lérins and the episcopal see of Arles. It had to have been written after the year 416, the publication date of the masterpiece On the Trinity by the North African bishop Augustine of Hippo (since it obviously depends on that great work)5 but before the end of Caesarius’s episcopate in 542 (since he quotes it in the sermon collection mentioned above). Suggested authors are Hilary of Arles and Vincent of Lérins in the early fifth century, and Caesarius of Arles himself in the sixth. J. N. D. Kelly convincingly argues for late fifth- or early sixth-century authorship by someone under Caesarius’s tutelage (but not Caesarius himself), and he concludes,

The connexion of the creed with the monastery at Lérins, its dependence on the theology of Augustine and, in the Trinitarian section, on his characteristic method of arguing, its much more direct and large-scale indebtedness to Vincent, its acquaintance with and critical attitude towards Nestorianism, and its emergence at some time between 440 and the high noon of Caesarius’s activity—all these points, as well as the creed’s original function as an instrument of instruction, have been confirmed or established by our studies. . . . Only the name of the actual author eludes us.6

Lérins Abbey [© Baker Publishing Group]

In addition to the question of the time and place of writing, another important issue is what the function of “The Catholic Faith” was. If it was not originally a creed, what was it? To answer this question, we need to go back to the collection of Caesarius’s sermons in which we first find the document. In the preface, from which we quoted at the beginning of this chapter, Caesarius indicates that “all clergymen, and laymen too” should be familiar with the faith. The focus on clergy in this assertion suggests that the initial purpose of the document was to provide a template that clergy could use to master the central theological dogmas of the Christian faith. While laypeople are mentioned, they may well have been secondary in Caesarius’s mind. Be that as it may, the document was originally meant to be studied and mastered, not to be recited liturgically. The Athanasian Creed was also cited by a council held around 670 in Autun in Burgundy (central France today). The council decrees, “If any priest or deacon or cleric cannot recite without mistake the creed which, inspired by the Holy Spirit, the apostles handed down, and the Faith of the holy primate Athanasius, he should be episcopally censured.”7 Again, we see that the primary audience of the document was the clergy.

Over time, as the prestige of “The Catholic Faith” grew, it began to be inserted into prayer books for liturgical use. This started in the late eighth century, and in the ninth century it began to be recited, and even sung, as part of the daily services. The document was still used as a tool for educating and examining clergy, but its growing place in the liturgy meant that, for the first time, it began to be regarded as a creed. By the middle of the thirteenth century, medieval writers began to speak of three creeds, and the Athanasian Creed’s place next to the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds was assured. A document written (as far as we know) by a single person rather than by a council or by the hand of liturgical development, and intended for educational purposes rather than liturgical ones, had become a creed with staying power.8

The Structure of “The Catholic Faith”

The Athanasian Creed is a masterpiece of balanced affirmations presented in almost poetic form. It consists of forty-two verses, each containing a single assertion or proposition that is directly linked to those before and after it. The verses are usually numbered, and in this chapter we cite them by verse numbers. Unlike any of the creeds we have encountered thus far, “The Catholic Faith” is not structured either around the three persons of the Trinity or around the events of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. Instead, it is organized into two major sections, one on the Trinity as a whole (vv. 3–28), rather than separate articles on each of the persons, and the other on the incarnation and life of Christ (vv. 29–41).

At the beginning and end of the document are affirmations that the faith described in these two major sections is the catholic faith (vv. 1–2, 42). Let us first look at these framing statements.

1Whoever desires to be saved must above all things hold the catholic faith.

2Unless one keeps it in its entirety inviolate, one will assuredly perish eternally.

42This is the catholic faith. Unless one believes it faithfully and steadfastly, one will not be able to be saved.9

One should notice immediately that the focus of this document is much different from any of the creeds we have seen previously. The early creeds covered in chapter 2, as well as the Nicene Creed and Apostles’ Creed later, begin with the affirmation “I believe” or “we believe,” and the focus is on the persons in whom we believe. This document begins not with someone in whom we believe, but with a body of beliefs—the catholic faith—that we must hold. Furthermore, this body of beliefs is regarded as a whole that one must “hold” and “keep” in its entirety in order to be saved. We have moved from creeds that profess our allegiance to God, to his Son, and to his Spirit (remember our mantra from the first chapter: the one to whom we belong is the one in whom we believe), to a document that commands us what to believe in order to be saved. To say it differently, we have moved from faith in someone to beliefs about something, from faith in the God who has sent his Son and Spirit for our salvation to belief in doctrines about the Trinity and the incarnation.

This shift may or may not be striking to you. As a guess, we suspect that the more familiar you are with Western theology, the less surprising (or even noticeable) this shift will be to you. Why? Because the Athanasian Creed reflects the direction that Western theology was already heading at the time of its composition. Subsequent Western theology in the Middle Ages and later continued this focus on doctrines, on things that we must (or should, or may, or do, or do not, or cannot) affirm. That shift has distinct advantages, most notably that it enables great theological precision (as is apparent from most substantial volumes of Western theology by both Catholics and Protestants). But at the same time, we should recognize what is lost in the process. Affirming truths about God is not the same thing as dedicating one’s life to God. Assent to doctrines does not necessarily imply allegiance or faith. By shifting the focus to doctrines, the Western church opened up the possibility that systematic theology might become divorced from the actual living of a life dedicated to God, his Son, and his Spirit. This divorce does not always take place, and it is surely unintentional when it does, but notice that what makes the divorce possible is the shift from persons to doctrines, from the ones in whom we believe to the things that we believe.

As we recognize that the Athanasian Creed represents a shift in the way the Christian faith is articulated, let us turn to its teaching on the Trinity and the incarnation to see how this shift plays out.

The Trinitarian Teaching of “The Catholic Faith”

The section on the Trinity (vv. 3–28) begins as follows:

3Now this is the catholic faith, that we worship one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity,

4without either confusing the persons or dividing the substance.

5For the Father’s person is one, the Son’s another, the Holy Spirit’s another;

6but the Godhead of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit is one, their glory is equal, their Majesty coeternal.

Here we should acknowledge the importance of the word “worship,” which mitigates to some degree the claim we made in the previous section. This document is not merely about concepts, about doctrines. It stresses the one God whom we worship. Remember that the Nicene Creed affirms that the Holy Spirit is “worshiped and glorified together with the Father and Son,” and the statement in verse 3 of this document that “we worship one God in Trinity” seems to be getting at the same truth. However, the very next phrase, “Trinity in unity,” shifts the focus from the persons themselves to the concepts. Verse 4 introduces the terms “person” and “substance,” and the phrasing of verse 5 clearly focuses on concepts rather than on the persons themselves. The writer could have asserted, “The Father is one person, the Son is another, and the Spirit is another.” That would have kept the focus on the persons themselves, while stressing that they are distinct as persons. But by claiming “the Father’s person is one, the Son’s another, the Holy Spirit’s another,” the writer accentuates the concept of person over the persons themselves. Interestingly, verse 7 is more successful at focusing on the persons, because it stresses what they share: Godhead, glory, and eternal majesty.

The document continues its discussion of unity and Trinity by focusing on attributes that the persons share:

7Such as the Father is, such is the Son, such also the Holy Spirit.

8The Father is increate, the Son increate, the Holy Spirit increate.

9The Father is infinite, the Son infinite, the Holy Spirit infinite.

10The Father is eternal, the Son eternal, the Holy Spirit eternal.

11Yet there are not three eternals, but one eternal;

12just as there are not three increates or three infinites, but one increate and one infinite.

13In the same way the Father is almighty, the Son almighty, the Holy Spirit almighty;

14yet there are not three almighties, but one almighty.

15Thus the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit God;

16and yet there are not three gods, but there is one God.

17Thus the Father is Lord, the Son Lord, the Holy Spirit Lord;

18and yet there are not three lords, but there is one Lord.

19Because just as we are obliged by Christian truth to acknowledge each person separately both God and Lord,

20so we are forbidden by the catholic religion to speak of three gods or lords.

Notice that to some degree this paragraph follows the pattern of earlier theology discussed in chapter 4. Treating the substance or essence of God as a set of attributes, earlier theologians taught that Father, Son, and Spirit all share each of those characteristics. So also here: Father, Son, and Spirit are each uncreated. Each is infinite. Each is eternal. Each is almighty. Thus, each is God, and each is Lord.

At the same time, however, there is a difference here. Following Augustine, the author of “The Catholic Faith” does not treat the attributes as characteristics that God has; he treats them as what God is.10 So, for example, he asserts that even though Father, Son, and Spirit are each almighty, there is one almighty, not three. An earlier theologian, or an Eastern theologian from this time period, would have been more likely to say that there are three who are almighty, but since they share all power, they constitute one God and Lord, not three. In the hands of this writer, the person-centric focus of that earlier way of speaking is transformed into an attempt to balance the concepts of unity and Trinity by asserting in a quasi-mathematical way that three persons are each almighty, but there is one almighty, not three. A new focus on concepts rather than persons, and a new emphasis on what one could call “mathematical symmetry” as a tool to deal with the Trinity, are reflective of shifts in the Western theological world after Augustine.

Having discussed the unity of the persons in this new, Western way, the author of “The Catholic Faith” turns to the relations between the persons:

21The Father is from none, not made nor created nor begotten.

22The Son is from the Father alone, not made nor created but begotten.

23The Holy Spirit is from the Father and the Son, not made nor created but proceeding.

24So there is one Father, not three Fathers; one Son, not three Sons; one Holy Spirit, not three Holy Spirits.

25And in this Trinity there is nothing before or after, nothing greater or less,

26but all three persons are coeternal with each other and coequal.

27Thus in all things, as has been stated above, both Trinity in unity and unity in Trinity must be worshipped.

28So one who desires to be saved should think thus of the Trinity.

This paragraph shows the same desire for mathematical symmetry that we have seen throughout the trinitarian section, but its main affirmations are identical to what earlier theologians had said, with one exception. Like earlier theologians and creeds, this document emphasizes the equality and eternity of the three persons. Like earlier theologians and creeds, it stresses that the Father is from nothing and the Son is from the Father, not made but begotten (see the Nicene Creed’s “begotten not made”).

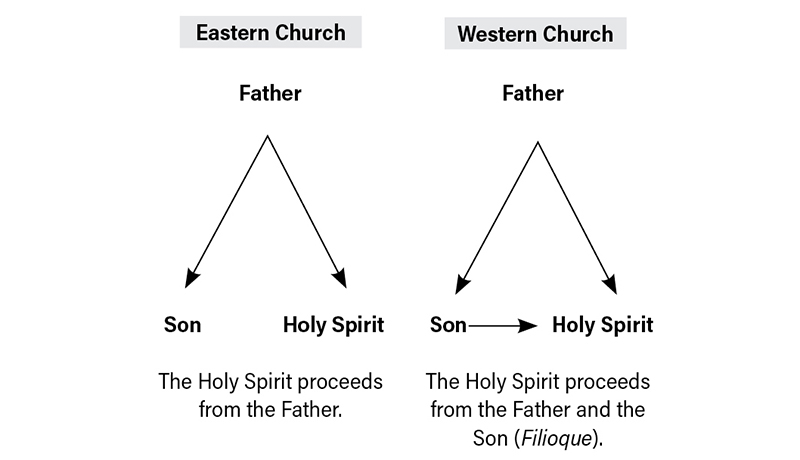

The exception, though, is that “The Catholic Faith” asserts, “The Holy Spirit is from the Father and the Son, not made nor created but proceeding.” This is an early affirmation of the “double procession of the Holy Spirit” or the Filioque. The Latin word Filioque means “and from the Son,” and both the word and the phrase “double procession” refer to the affirmation that the Holy Spirit eternally proceeds from both of the other persons, not just from the Father.11 Remember that the Nicene Creed has affirmed the procession of the Holy Spirit “from the Father,” without commenting one way or another on whether he also proceeds from the Son. In the West it was common for theologians to affirm the double procession of the Spirit, whereas Greek theologians tended either to disavow any such double procession or to use the phrase “from the Father through the Son” rather than “from the Father and the Son.”

The question of what difference it makes whether one affirms or denies the Filioque is a complicated one that later played a role in the eventual schism between the East and the West. For now, it is sufficient for us to recognize that if one denies the Filioque, the implication is that the Father, as a person, is the focus of trinitarian doctrine. The Father is uncaused, from no one and nothing. He is God pure and simple. The Son is God because of his eternal relation to the Father—he is eternally begotten from him. The Spirit is God because he, too, has an eternal relation to the Father—he eternally goes forth or proceeds from him. This way of speaking maintains the focus on the persons that we have argued was characteristic of early trinitarian theology. In partial (but by no means complete) contrast, the affirmation of the Filioque is usually related to a view of the Trinity that focuses on mathematical symmetry, the balancing of oneness and threeness. In such a model, drawing a line (metaphorically speaking) connecting the Son and the Spirit, to go along with the lines already drawn connecting the Father and Son and connecting the Father and Spirit, provides balance and helps to illustrate the equality of the persons. The debate over the Filioque thus has to do more with which model of the Trinity one uses than with the actual question of whether one can demonstrate biblically that the Spirit proceeds from both of the other persons. We will return to the question of the Filioque in chapter 10. Let us now turn to the christological teaching of the Athanasian Creed.

“The Catholic Faith” on the Incarnation

In this section of the document, the author adheres much more closely to the creedal language of those who have gone before him. The focus throughout is on the person of God the Son. While the Nicene phrase “came down” does not occur, the incarnation as an action by which the eternal Son came to earth to suffer for us is clear. The following is the first paragraph of this section:

29It is necessary, however, to eternal salvation that one should also faithfully believe in the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ.

30Now the right faith is that we should believe and confess that our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is equally both God and man.

31He is God from the Father’s Substance, begotten before time; and he is man from his mother’s substance, born in time.

32Perfect God, perfect man composed of a rational soul and human flesh,

33equal to the Father in respect of his divinity, less than the Father in respect of his humanity.

Notice in verse 30 that the first assertion regarding “our Lord Jesus Christ” is that he is the Son of God. This affirmation precedes the insistence that he is “equally both God and man” and sets the stage for the descriptions of verses 31–33. This Son of God is “God from the Father’s Substance,”12 and as such, was begotten before time. He (clearly “the same one,” although this document does not spell that out) is also “man from his mother’s substance, born in time.”13 The structuring of the paragraph around a single person, the eternal Son, who has always been God and who is now man as well, is reminiscent of the Chalcedonian Definition. Notice also the affirmation that Christ’s humanity includes “a rational soul and human flesh.” This assertion was almost ubiquitous after the late fourth century as a way of disavowing Apollinarianism.

The next paragraph is as follows:

34Who, although he is God and man, is nevertheless not two but one Christ.

35He is one, however, not by transformation of his divinity into flesh, but by the taking up of his humanity into God;

36one certainly not by confusion of substance, but by oneness of person.

37For just as rational soul and flesh are a single man, so God and man are a single Christ.

In verses 35–36 we see language almost identical to that which Vincent of Lérins earlier used to combat Nestorianism,14 as our author insists that the eternal Son did not merely indwell the man Jesus; rather, he took humanity into his own person. The body-soul analogy, while certainly incomplete, was almost universal as a description of the christological union.

Finally, “The Catholic Faith” discusses the actions of the incarnate Christ.

38Who suffered for our salvation, descended into hell, rose from the dead,

39ascended to heaven, sat down at the Father’s right hand, whence he will come to judge living and dead:

40at whose coming all men will rise again with their bodies, and will render an account of their deeds;

41and those who have behaved well will go to eternal life, those who have behaved badly to eternal fire.

Here, along with a standard recitation of the events of Christ’s earthly life, two things are noteworthy. First, the Athanasian Creed affirms the descent into hell, which by this time had been added to the Apostles’ Creed as well. Second, in contrast to the Apostles’ Creed (which merely affirms that Christ will judge the living and the dead), this document affirms the basis for Christ’s judgment: the deeds/behavior of those being raised from the dead. To Protestant ears, the focus on behavior in verse 41 may be unnerving. If we are on the lookout for anything that smacks of “works righteousness” and a denial of justification by faith, we seem to have found the smoking gun here.

Well, maybe, or maybe not. Whenever our works-righteousness antennae are engaged, we need to remember that there is a lot of “works” language in the New Testament, including references to judgment on the basis of works.15 Of course, in the big picture, what we do is the fruit of the transformation that God has already made in us through Christ and the Holy Spirit, but if biblical authors can refer to judgment on the basis of works without always painting the big picture, so can the Athanasian Creed. We should not jump immediately to condemn a writing on the basis of a statement such as this.

At the same time, Protestant fears that this document is sliding into medieval works righteousness are probably somewhat justified. The document began by insisting that in order to be saved, one has to keep “the catholic faith” (a body of doctrines). Now, at the end, it is claiming that judgment will be based not merely on assenting to the doctrines, but also on works. Here we see, at the beginning of the Middle Ages, a movement toward insisting on works in addition to faith, which later incited the reaction that we call the Reformation. But notice the logic of this movement. If one reduces faith from allegiance to a person down to assent to doctrines, then one needs to add something in order to do justice to the biblical picture of Christian life. But if one were to maintain the focus on faith as allegiance to a person (again, remember “the one to whom we belong is the one in whom we believe”), then it would be fairly obvious that such allegiance would lead to a transformed life, a life characterized by good works. In other words, the felt need to bring works into a document like this may stem from a shift away from allegiance to God, his Son, and his Spirit. The divorce of theological language from Christian life, already underway at the time “The Catholic Faith” was composed, may have contributed to what eventually was a skewed perception of the relation between faith and works by the late Middle Ages.

Conclusions

The Athanasian Creed certainly is a creedal anomaly. It was not composed by the person whose name it bears or even in the language he spoke or the part of the Christian world where he lived. It was not originally intended as a creed and only very gradually began to be used liturgically. It has rarely been accepted outside the Western Christian world and has recently fallen into disfavor even there. It is hardly used in public worship today. Yet it did have a lot of staying power and rose to the rank of the Western church’s third creed in the High Middle Ages, a position it still holds in Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism today, if nowhere else.

What are we to make of this odd document? We have seen that in spite of its unusual origin and historical pathway, it does have much to teach us. Its balanced phrases provide a simple way of emphasizing truths as complex as, for example, that Father, Son, and Spirit share the same attributes, or that the same Son is both eternal in his begetting from the Father and temporal in his birth from Mary. While it is hard to recite, it is worth reading and meditating on. That, in fact, was what it was originally meant for!

Nevertheless, there are problems with the document as well. We have seen that the trinitarian discussion in “The Catholic Faith,” while not actually at odds with the earlier creeds (Eastern and Western), does represent a significant shift in the way the doctrine of the Trinity is articulated. At the time of its writing, Western theology was beginning to strike out on its own course, and this document both reflected and, as it became more widely used, cemented that new direction. Readers of this book may disagree on whether that new direction was a good one, but it should at least be clear that the shift from focusing on the trinitarian persons as the ones in whom we believe, to focusing on doctrines, is potentially dangerous.

With the writing of the Athanasian Creed around the year 500, we bring the era of the creeds to a close, even though the Apostles’ Creed underwent some minor revisions later. In part 2 we will examine the very different ways in which the Eastern and Western churches explored the theology of the creeds from 500 to 900. As we will see, the different directions that they took eventually led to the split between East and West into what we today call Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. To that story we now turn.

1. See J. N. D. Kelly, The Athanasian Creed (New York: Harper & Row, 1964). Kelly’s work has so thoroughly settled the historical questions related to the Athanasian Creed that there has been little scholarly work on that document subsequently. Much of this chapter is indebted to Kelly’s work (as indeed much of the discussion in the previous chapters has been indebted to his work on other creeds).

2. Scholars today normally call it the Quicunque (Latin for “whoever”), which is the first word of the document as written in Latin.

3. See Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 2–3.

4. See Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 42–48.

5. We will turn our attention to Augustine of Hippo in depth in chap. 9.

6. Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 123.

7. See Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 41.

8. Today the Athanasian Creed is recited on Trinity Sunday (in May or June) in Roman Catholic and in many Lutheran churches. Its use in Anglicanism is declining, although some churches still use it on select days in the daily services.

9. Here and in the subsequent sections of this chapter we use the translation from Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 17–20. Also in CCFCT 1:676–77.

10. For a discussion of the way Augustine’s trinitarian theology influenced this document, see Kelly, Athanasian Creed, 80–84.

11. In John 14:16 Jesus describes the Father as sending the Holy Spirit, and in John 15:26 he says that he will send the Spirit from the Father. Clearly, then, both Father and Son send the Spirit into the world to accomplish his mission. But in John 15:26 Jesus also affirms that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, and this is the source of the language to that effect in the Nicene Creed. The question—which cannot be resolved merely exegetically—is whether the Son’s sending the Spirit into the world implies that the eternal procession of the Holy Spirit is also from the Son as well as from the Father.

12. Notice that this is a phrase from the Creed of Nicaea that was dropped in the final form of the Nicene Creed.

13. Even after Chalcedon it was common in the West to use the word “substance” rather than “nature” to describe the divine and human within Christ.

14. In his Excerpta, which have not been translated into English.

15. See, for example, the parable of the sheep and the goats in Matt. 25, as well as 2 Cor. 5:10 and Rev. 22:12, not to mention James 2.