10

Creedal Dissension and the East-West Schism

In the year 858, Constantinople was abuzz. Patriarch Ignatius had been on the episcopal throne for eleven years, but the Byzantine empress Theodora and her son Michael, both of whom supported Ignatius, were losing power. There were rumors that Bardas (Theodora’s brother) was involved in an incestuous relationship with his daughter-in-law, and when Ignatius publicly condemned Bardas, the ax fell on both the patriarch and the empress who had appointed him. Theodora was ousted in a coup, and Bardas took power as Caesar while leaving Michael nominally in power as emperor. Whether Ignatius was forced out by appropriate procedures or in some more underhanded way is not clear, but a legitimate patriarchal election followed, and a young layperson with a brilliant mind, a stellar education, and very good political connections was chosen as the next patriarch of Constantinople. His name was Photius.1

Ignatius was not without supporters, and they were livid about the replacement of their champion, a holy man with a genuine spiritual heart, with the aristocratic and perhaps a bit-too-well-connected Photius. One of Ignatius’s fans, the monk Theognostos, sneaked out of Constantinople (wearing secular garb rather than his monastic habit, to avoid detection) and made his way to Rome. There he became the source of (very likely distorted) intel about Caesar Bardas and Patriarch Photius, intel that he dutifully fed to Pope Nicholas I. Unlike the East, the West had a long-standing tradition barring the elevation of a layperson to the episcopacy without his first assuming a lower clerical rank, and Pope Nicholas therefore was inclined to side with Ignatius in the contested election. At the same time, Nicholas was primarily concerned about the question of whether the newly converted tribes in Illyricum (modern Bulgaria) would come under the jurisdiction of Constantinople or of Rome. The West had recently won one such jurisdictional battle, as the Moravians (in modern Slovakia) had allied with Rome and the Franks, even though they were Slavic and had gained a written alphabet for their language through the work of Byzantine missionaries, Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius. Nicholas was hoping for a similar outcome with the Bulgarian tribes, and he tried to use the disputed election as leverage to gain jurisdiction over Bulgaria. He wrote a courteous letter to Photius, to which the new Constantinopolitan patriarch responded by declaring that the East did not acknowledge the validity of any such prohibition against elevating laypeople to the episcopate.

Both Moravia and Illyricum were in dispute between the Franks and the Byzantines. [© Baker Publishing Group]

At this point, the lid blew off the pressure cooker, and long-simmering tensions boiled over. Eventually, the tensions led to a schism between East and West that persists to the present day, and history later granted Photius the dubious distinction of playing the pivotal role in that schism. In the East he is known as Photius the Great. In the West he has long been regarded as the originator of the “Photian heresy.” How did Photius bring about such an enormous rift in the church? And what does this have to do with the creeds and confessions? To answer these questions, we need to back up, gather together various threads of the story that we have already considered, and then return to the conflict between Photius and Nicholas.

The Emerging Political Rivalry between Constantinople and Rome

We saw in the previous chapter that since Rome was the only patriarchal see in the Latin-speaking world, it was easy for Latin Christians to regard Rome as possessing authority over other episcopal sees. In the East, as we have also seen, the presence of four patriarchal sees (Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and Constantinople) meant that a pattern of shared authority naturally developed, and it was more difficult for any single episcopal see to claim unique authority over others. As a result, although in theory Rome believed itself to hold authority over all of Christendom, the popes rarely tried to assert that authority over the Eastern church. (Gregory the Great’s refusal to grant the patriarch of Constantinople the title “ecumenical patriarch” was a noteworthy exception.) But by the early ninth century, the political tension between Rome and Constantinople had become increasingly severe, for several reasons.

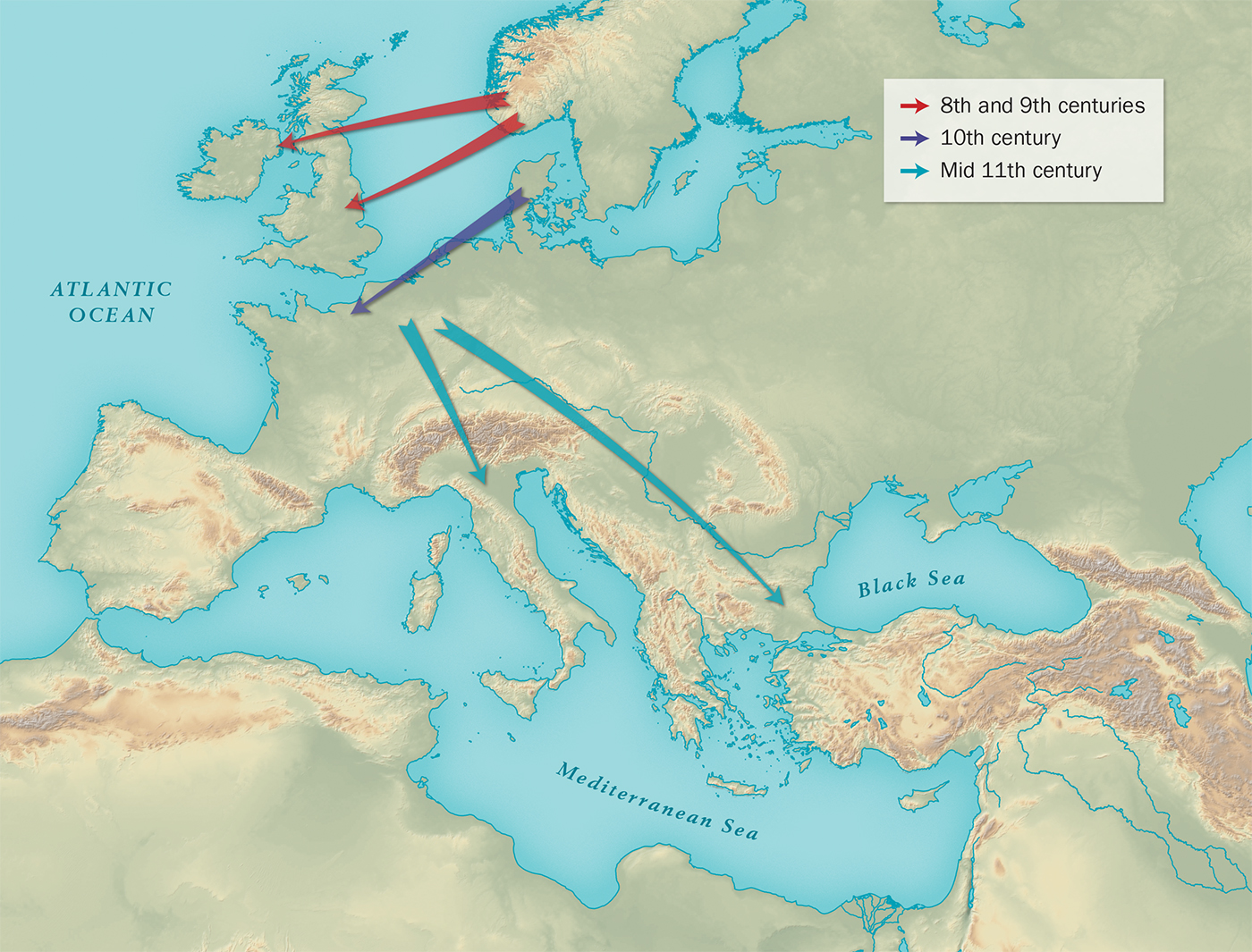

First, the rise of Islam redrew the map of the Christian world. Christianity in Latin North Africa was destroyed, leaving the Western Christian world without its erstwhile intellectual center and forcing the Latin church to move northward and westward, deeper into the Frankish realms and Britain, and eventually into the Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands today) and Scandinavia. In the East, Egyptian and Syrian Christians had to adapt to second-class status within newly Muslim kingdoms, and even the patriarchal sees of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria had to function in Muslim-ruled environments. This left Constantinople as the only Eastern patriarchal see that functioned in tandem with a Christian imperial government. Thus, the situations of Rome and Constantinople—cities whose episcopal sees also wielded political power that was almost unchallenged—became more similar, and rivalry between them began to emerge.

The early expansion of Islam [© Baker Publishing Group]

Second, the rise of the Franks, to which we have alluded at several points in the previous chapters, was accompanied by an increasingly close alliance between the Frankish government and the papacy. After Charles Martel’s victory over Muslim forces at the Battle of Tours in 732, his descendants Pepin the Short and especially Charlemagne worked so closely with the papacy that the Frankish capital of Aachen (in northwestern German today) became a virtual “new Rome,” paralleling Constantinople as new Rome in the East. This Franco-Roman alliance brought about a new flourishing of education, scholarship, and the arts in Western Europe, the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century. This renaissance heightened tensions between East and West because it meant that Byzantium was no longer the undisputed center of Christian civilization. The regions of Europe north of the Alps—once the home of “uncivilized” tribes so backward that they posed no threat to the high culture of Constantinople—were now becoming an intellectual and cultural force to be reckoned with, and Byzantium did not always welcome the flourishing of its younger sibling with enthusiasm. This, too, added to the growing tension and rivalry between Rome and Constantinople.

Third, the increasing power and prestige of the papacy in the Western Christian world was accompanied and justified by appeals to documents that were believed to date from the early Christian centuries but that had actually been composed more recently.2 In about 500, forged documents appeared that insisted no council (not even an ecumenical council) was valid unless approved by the pope. In the ninth century, even more spectacular forgeries emerged, the Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals (which professed to be papal letters from the fourth through eighth centuries) and the Donation of Constantine (allegedly a letter from Constantine himself to Pope Sylvester, granting him the imperial buildings in Rome and authority over the Western world as he prepared to move the capital to Constantinople). These forged documents stressed papal supremacy very strongly and served to bolster that conviction in the ninth-century Frankish world. Pope Nicholas accepted them without question and used them to justify a view in which the pope held power over the entire Christian world.3 Thus, while the rise of Islam and the Frankish (Carolingian) renaissance helped to pit Rome against Constantinople, it was the Western view of papal power that proved to be the flashpoint igniting the combustible mixture. This brings us back to the disputed election of 858.

Nicholas, Ignatius, and Photius

After Photius’s dismissive response to the papal letter, Nicholas sent two emissaries to Constantinople in 861. Their main concern was to gain papal jurisdiction over the Bulgarian tribes, but their major argument—directed not at Photius himself but at Emperor Michael, whose Caesar had secured Ignatius’s removal—was that an emperor could not depose a patriarch without appeal to the Roman see. Michael replied that while the resolution of dogmatic issues required Roman participation (in other words, doctrinal matters could not be established by merely regional synods; they required participation from the whole church), there was no dogmatic issue at stake here4 and therefore no need to consult the pope. Nevertheless, Michael agreed to a retrial of Ignatius before the Roman legates, as a courtesy to Nicholas. At this trial, Ignatius was less than polite to the Roman emissaries, and not surprisingly, they and the council gathered around them ruled against him and in favor of Photius. But they could not prevail on the East to relinquish its claim to Bulgaria, and, in fact, soon after this Michael actually invaded Bulgaria, forcing its prince, Boris, to convert to Byzantine Christianity rather than Roman. Nicholas was furious and used his emissaries’ diplomatic failure as an excuse to sack them and to hold a synod of his own in Rome in 863, at which Photius was deposed and Ignatius “reinstated.”

At this point, things quickly went from bad to worse. Michael wrote what may have been the most outlandish letter in Byzantine diplomatic history,5 in which he evidently ascribed Pope Nicholas’s reinstatement of Ignatius to the ignorance of a backwater politician, while again arguing that the pope had no right to intervene in the internal affairs of Constantinople. Nicholas countered with a long justification of papal supremacy over all affairs—procedural and liturgical as well as doctrinal—of the whole church. He also held out an unexpected carrot: if both Ignatius and Photius would come to Rome with their supporters, Nicholas himself would hear the dispute. Naturally, this invitation was ignored.

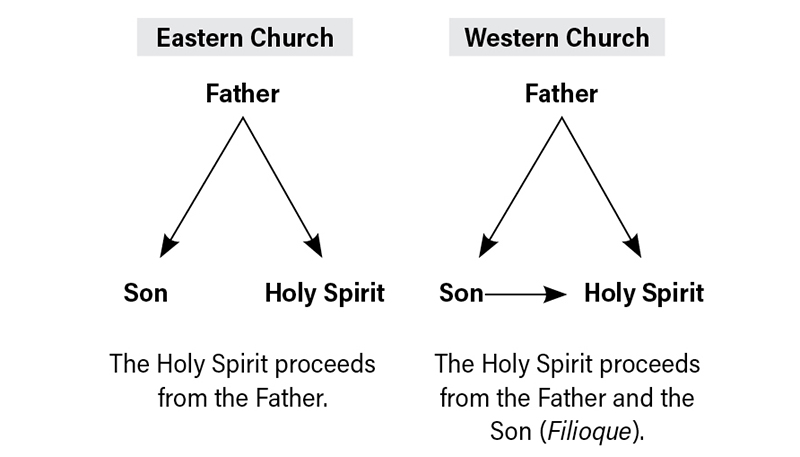

At this point, it should be clear that the controversy was about questions of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, especially about whether the primacy of the pope extended to the point of his being able to intervene in internal matters of procedure in other sees. The tension was astronomical, but it was about ecclesiastical politics, not really about doctrine. In fact, we should remember that part of Michael’s justification for not consulting Rome on the matter was that no doctrinal issue was at stake. Again, we wonder, what does this have to do with the creeds? At this point, in about the year 865, the answer to that question had to be “Nothing.” But then Photius introduced into the controversy the most devastating of all charges: the Roman see’s support of Ignatius in the struggle was worthless, because Rome was heretical. It had accepted the heretical notion that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and from the Son. Thus, with a single blow he raised the stakes of the controversy and made it into a theological debate, indeed even a creedal debate. In the process, he also bequeathed to the controversy the name by which it is normally known: the Filioque controversy. We have deliberately withheld that name up to this point in order to show how thoroughly this dispute began as a political, jurisdictional clash, not a doctrinal one. But now it became a doctrinal dispute, or at least it was being dressed up as one. So we need to turn back to the Filioque and to the way Photius used the issue against the West.

The Filioque as a Wedge Issue

In 866, Photius wrote an encyclical letter to the Eastern Christian bishops,6 laying out his case against the Western church. His initial criticism of the West had to do with the Bulgarian tribes and showed the degree of ill will that now overshadowed the situation:

For that nation had not yet been honoring the true religion of Christians for two years when impious and ill-omened men (for what else could one of the pious call them?) arising from the darkness (for they sprang from the Western regions), alas—how shall I narrate the rest? These men fell upon the nation newly established in piety and newly formed, like lightning or earthquake or a hailstorm, or rather, to speak more appropriately, like a solitary wild beast, and with feet and teeth, that is with the pressure of a shameful way of life and corrupt doctrine, ravaged and violated (as far as depended on their own audacity) the vineyard of the Lord, beloved and newly planted.7

The key phrase here is “shameful way of life and corrupt doctrine,” and the way of life he criticized had to do with matters of Christian practice on which the West differed from the East. The Westerners fasted on Saturday but proscribed fewer foods during the Lenten fast, did not allow presbyters to marry, and repeated the rite of chrismation in certain circumstances.

The “corrupt doctrine,” of course, was the Filioque. After listing the differences in practice, Photius wrote, “Besides the aforementioned nonsense, they even attempted to adulterate with bastard ideas and interpolated words (O scheme of the devil!) the holy and sacred creed, which holds its undisputed force from the decrees of all the ecumenical councils; they make the novel assertion that the Holy Spirit proceeds not from the Father alone but also from the Son.”8 Here we see the charge that the Westerners had interpolated the Nicene Creed, which certainly was true. As we have seen, the word Filioque made its way into the creed in Spain prior to the end of the sixth century. By stating that the creed held its force from the decrees of all the ecumenical councils, Photius alluded to one of the key reasons for opposing the Filioque. Whatever one may think of the theology of the Spirit’s procession, the Nicene Creed was approved by an ecumenical council—the Second in 381—and reaffirmed by all subsequent ecumenical councils without the Filioque. Therefore, it was reasonable to argue, as the Eastern church did, that it could be amended only through another ecumenical council.

The Filioque controversy

This point serves to highlight the difference between the Nicene Creed and other creeds, as well as the different attitudes toward creeds in East and West. As we emphasized earlier in this book, the Nicene Creed was the only creed formally approved by the entire church, a fact that placed it in a different category from even the Apostles’ Creed. Such a universally approved statement should not be tampered with, according to the Eastern church. So to the East, the issue was not just the theological question of whether the Spirit proceeds from both other persons of the Trinity; it was at least as much the question of whether and how one could legitimately modify the creed. The West, in contrast, saw the issue as being merely the theological question, and perhaps part of the reason for this was that the major creed to arise in the West, the Apostles’, was well known to have undergone a long period of development. As a result, the idea that a change might be made in order to articulate a theologically accurate point was not objectionable on creedal grounds in the West.

Photius then launched into a long tirade against the theology of the Filioque. His arguments were many and at times descended to the level of caricaturing the Western understanding, whether intentionally or not. Nevertheless, his basic idea was that affirming the double procession of the Spirit implied that there were two principles or sources of deity, and this amounted to placing the Father and the Son in opposition to each other as separate deities.9 This is surely not what any Western theologian has ever meant, because one could, and many did, insist that the Father is indeed the sole source of deity while still arguing that the Son is involved in the Spirit’s eternal procession. The Spirit proceeds from the Father with the involvement of the Son or through the Son. This was, in fact, what Maximus the Confessor had proposed in the seventh century, as a way of reconciling the Eastern and Western views on the matter.10

As a purely theological matter, the question of the Spirit’s procession might well have been one on which East and West could have come to terms without splitting the church. But, as our discussion has shown, and as Photius’s severe caricature of the Western position also demonstrated, he was not interested in coming to terms. The Filioque was not actually the source of the controversy that bears its name, or even the main issue of that controversy. Rather, the dispute was about jurisdiction over the Bulgarian tribes and about Rome’s right to intervene in internal, nondoctrinal matters in Constantinople. The Filioque was simply a wedge issue, which Photius inserted into the controversy late in the day in order to rally the East to oppose the West, and in the process to affirm him (rather than Ignatius) as the proper patriarch of Constantinople.11

The “Fate” of the Filioque

In 867, Photius held a small synod that deposed Pope Nicholas for the “crimes” that he had laid out in his encyclical letter the previous year. But in the same year, both Caesar Bardas and Emperor Michael were murdered, and Michael’s adopted son Basil assumed the throne even though he had been Bardas’s murderer and was suspected of being involved in the plot against Michael. Later that year, Pope Nicholas died (amazingly, with no foul play involved!) and was replaced by Hadrian II. This sweeping changing of the guard in both East and West left Photius in a greatly weakened political position, and synods in both Rome and Constantinople in 869–70 ruled him deposed and Ignatius reinstated as patriarch. The Constantinopolitan council (belatedly) affirmed the Seventh Ecumenical Council and the primacy of the pope in all matters, doctrinal as well as ecclesiastical. This council is today regarded by Roman Catholics as the Eighth Ecumenical Council, and the Catholic Church has continued to name its own councils as “ecumenical” up to the present time. The Filioque is absent from the acts of this council.

Again, however, the death of crucial players led to a change in the situation. Pope Hadrian died in 873 and was replaced by John VIII. Ignatius died in 877, after recommending that Photius (with whom he had been reconciled) replace him. Emperor Basil agreed, but this created a delicate need to gloss the acts of previous councils so as to bring about Photius’s reinstatement without seeming to undermine the authority of church councils. So yet another council was held in Constantinople in 879, which secured (with some difficulty) Photius’s legitimacy and left the question of jurisdiction over the Bulgarians in the hands of the emperor. At the council, the Nicene Creed was read out without the Filioque, and a condemnation was pronounced on those who would venture to add to the creed.12 Thus, the act of interpolating the creed was explicitly condemned, although the theology of the double procession per se was still not addressed.

Again, we need to recognize that the issue of the Spirit’s procession was never central to the so-called Filioque controversy, and, indeed, it was not central to the later breach in fellowship between Rome and Constantinople either. It has remained an issue of theological contention up to the present, and Photius’s arguments about the negative implications of affirming the double procession have provided many Eastern theologians with justification for remaining separate from the West.13 But in none of the flare-ups of controversy between East and West was it ever the main source of tension.

Low Points of a Growing Schism

During these complicated political maneuverings from 858 to 879, there was a brief period in the 860s during which Rome and Constantinople were technically out of fellowship with each other while the former affirmed Ignatius and the latter Photius as the rightful patriarch of Constantinople. This brief schism was a harbinger of things to come, as tensions between East and West continued to escalate from the ninth through thirteenth centuries. There were several other tense points along the way to the Great Schism that are worth describing briefly, even though they took place after the year 900, when this part of our book technically ends.

In the middle of the eleventh century, friction between Rome and Constantinople again reached a critical point, largely because of the Viking invasions of Europe in the ninth through eleventh centuries.14 The Norsemen from Scandinavia—accomplished sailors and fierce warriors—violently captured and subdued vast territories in the British Isles, northern France, the Low Countries, and Germany.15 By the middle of the eleventh century, they were threatening regions in southern Italy and even took Pope Leo IX captive in 1053. Since some churches in southern Italy were Greek-speaking and under the jurisdiction of Constantinople, both East and West had a stake in warding off the Viking threat. At the same time, a new slate of issues on which Eastern and Western practice differed rose to the surface, dominated by the question of whether the Eucharist should be celebrated with unleavened bread (as in the West) or leavened bread (as in the East).

In the spring of 1054, Pope Leo IX dispatched a delegation of three legates, led by Cardinal Humbert, to Constantinople. Humbert knew both Greek and Latin, but he was a headstrong man with little interest in diplomacy and thus a rather poor choice for the assignment. To make matters worse, Leo died while the delegation was en route, thus leaving Humbert technically without papal authority for his demands. Humbert was convinced that papal supremacy and Roman worship practice were both universal, and during the political negotiations he insisted on both of these. He also raised the issue of the Filioque through the outlandish claim that the East’s removal of the word from the creed made it guilty of heresy. In spite of Humbert’s intransigence, the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX had advised Patriarch Michael Cerularius to be tactful, and he tried to do so as long as he could. But not surprisingly, the negotiations quickly broke down.

Viking invasions [© Baker Publishing Group]

On July 16, 1054, Humbert and his two fellow legates went to the great cathedral Hagia Sophia, but instead of worshiping with the Greeks, Humbert placed a bull of excommunication on the altar, directed at Michael Cerularius and his supporters (not at the whole Eastern church). The document praised the emperor but accused the patriarch of many liturgical sins and, of course, of deleting the Filioque from the creed. A deacon tactfully removed it from the altar and handed it back to Humbert outside the church, and Humbert threw it on the ground as he and his associates hastily left the city. Eventually the bull found its way to Cerularius, who had it translated into Greek and reported to the emperor. Constantine IX had the Latin legates recalled to the city, and when they refused to explain their actions, he authorized Cerularius to pronounce an anathema. Cerularius called a hasty synod on July 24, 1054, which anathematized the authors of the bull, and subsequent hearsay insisted that the synod had actually condemned the entire Western church.

Historians disagree about the significance of these mutual anathematizations. While many point to 1054 as the date of the schism between East and West, others correctly recognize that the fateful event of that year was only one among many low points in the worsening relationship between the churches and that Christians at the time did not see the event as the source of the rift between them. Perhaps the best way to regard the saga of Humbert and Cerularius is to see 1054 as a convenient symbolic date in the middle of a four-hundred-year history of worsening separation between what came to be known as the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic communions. However much significance we ascribe to 1054, though, it is clear that (again!) the issue of the Spirit’s double procession played only a very minor role. Far more important, yet again, was the issue of papal supremacy over the entire church.

Be that as it may, as the eleventh century progressed, there was a far greater menace than separation between the churches looming in the Eastern Christian world. The Turks, a warlike people from central Asia, began to move into what we today call the Middle East, defeating the Arabs in Syria and Palestine, thus taking control of the Holy Land and moving into Asia Minor,16 thus threatening the Byzantine Empire. In the spring of 1095, at a small council in Piacenza (northern Italy) headed by Pope Urban II, a delegation was received from the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenos. This delegation asked for Western help in fighting off the Turkish menace, and its arrival set off the chain of events leading to the First Crusade. In November of that year, Pope Urban preached his famous sermon rallying people to the Crusade, and the first ships left in the spring of 1096. We will return to Pope Urban and the Crusades in chapter 12, but for now, only two aspects of the Crusades are directly relevant. The first is that among the many motivating factors, a prominent one was the desire to bring aid to the Greek Christians and thereby to help heal the relationship between Rome and Constantinople. Granted, it was the emperor, not the patriarch, who had asked for aid, but even so, Urban and many others in the West thought that the East might respond to magnanimous aid from the West by submitting to the pope and shoring up the precarious relationship. The Crusades began as—among other things—an attempt to bring military aid to besieged Christians in Constantinople.17

The conquest of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 [Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons]

The other aspect that is relevant to the story of the East-West schism was a tragic series of events that unfolded in the year 1204, as the Latins readied for the Fourth Crusade. In 1201–2, Venetian merchants (who stood to gain much from Latin control of the Middle East, because it would mean much easier trade with Asia) had engaged in a massive shipbuilding program to accommodate the huge contingent of Crusaders promised. When only about a third of the expected thirty-five thousand men turned up in Venice in April 1202, and thus far less money was available to pay back the shipbuilders, the endeavor was instantly in enormous debt. To repay that debt, the Crusaders were forced to attack and plunder Christian cities on the way to the Holy Land, until word came from Alexius IV (the former Byzantine emperor who had been sacked in a coup) that if they would capture Constantinople and restore him to the throne, he would make the patriarch of Constantinople subservient to the pope. With extreme reluctance, but seemingly little choice in view of the overwhelming debt they faced, the Crusaders turned the sword on the Byzantine capital. It fell on November 24, 1204, and the spoil was used to pay off the merchants. A Latin kingdom was established with a puppet patriarch, and although Pope Innocent III condemned the attack, he did not try to hide his delight that now all of Christendom was officially under his jurisdiction.18 The Byzantines recaptured Constantinople in 1261, but the Byzantine Empire never again regained its former glory. Eventually Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, and a half-millennium of Turkish rule over southeastern Europe began.

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 was essentially the final straw in relations between East and West. There were two major councils in the high and late Middle Ages that sought to repair the rift, one in Lyons (southeastern France) in 1274 and the other in Ferrara and then Florence (north-central Italy) in 1438–39. At both of these councils, and especially at the latter, significant progress was made on the Filioque, but the Western contingents also insisted on Eastern submission to the pope and compliance with Western liturgical practices. The memory of 1204 was fresh enough, even in 1439, that no assertion of papal supremacy ever gained a hearing in the East again. In the case of both councils, the agreements signed by the Eastern delegates were solidly rejected back in Constantinople.19

Conclusions

The schism between East and West was hardly the first split in church history, nor was it the longest-lasting one, since the christological schisms predated it by half a millennium and are also still ongoing today. But the split between Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches was the largest split in Christian history, sundering the vast majority of the church universal into two disunited halves. Furthermore, if one accepts the judgment that we have offered here—that the Filioque played only a minor role in the schism and would not, on its own, have split the church—then it becomes apparent that this was a rift occasioned by differences in practice and questions of papal authority, rather than doctrine per se. In fact, even when the Filioque was the issue, it was not so much the theology of the double procession per se that divided but the question of whether it was permissible to alter a creed approved by an ecumenical council. Thus, even the Filioque controversy itself was as much a matter of ecclesiastical authority as it was a doctrinal dividing line. That the rift was not about doctrine means that in some ways, this was the saddest split in Christian history.

Whatever date one gives to this schism, it is clear that the Greek and Latin churches had more or less separate histories from the thirteenth century forward. The West continued to address and develop the issues that had been important in Augustine’s thought, especially the sacramental mediation of grace and the relation between grace and human action. It also continued to press the issue of papal supremacy, now with little to check the growing role of the pope in all areas of society, since the churches that pushed back against the supremacy of the papal office were no longer in the picture. Eventually, all of these issues found their detractors, and the result of growing internal Western disagreement on these issues was the Protestant Reformation.

At the same time, the East followed its own path, only rarely responding to major Western developments.20 But as the Reformation broke, it became apparent that the Eastern Orthodox and the Protestants had at least one thing in common, an opposition to claims of absolute supremacy for Rome. This common starting point led to some tentative explorations of potential unity between Protestant Christianity and Eastern Orthodoxy and to the writing of Orthodox confessions of faith that in some ways parallel the great Protestant confessions. Thus we will have occasion to return to the Eastern Christian world in part 4 of this book. For now, though, we turn to the West and concentrate on medieval Roman Catholicism in part 3.

1. For the extended story of the Photian schism, see Henry Chadwick, East and West: The Making of a Rift in the Church, from Apostolic Times until the Council of Florence, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 95–184.

2. During the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century, Lorenzo Valla demonstrated that these documents were forgeries, and this demonstration helped set the stage for the Reformation. See Lorenzo Valla, On the Donation of Constantine, trans. G. W. Bowersock, The I Tatti Renaissance Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008).

3. See Chadwick, East and West, 95–102.

4. This was not quite true, since one of the issues was the fact that the West had been slow to recognize the authority of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, which led the East to wonder whether the Westerners actually favored iconoclasm. They didn’t.

5. We write “may have been” because the letter is not extant. We know it only through Nicholas’s reply.

6. Translated in CCFCT 1:298–308.

7. Photius, Encyclical Letter to the Bishops of the East 4, in CCFCT 1:299.

8. Photius, Encyclical Letter to the Bishops of the East 8, in CCFCT 1:300.

9. Photius, Encyclical Letter to the Bishops of the East 9–23, in CCFCT 1:300–303. See also the helpful summary of Photius’s argument in A. Edward Siecienski, The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy, Oxford Studies in Historical Theology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 101.

10. See Siecienski, Filioque, 74–86.

11. Some historians manage to tell the story of this controversy without even mentioning the Filioque. See, for example, F. Donald Logan, A History of the Church in the Middle Ages (London: Routledge, 2002), 92–97.

12. See Siecienski, Filioque, 104.

13. For example, the great twentieth-century Russian Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky calls the Filioque “the primordial cause, the only dogmatic cause, of the breach between East and West.” The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1976), 56.

14. For these events, see Chadwick, East and West, 206–18; Logan, History of the Church, 80–88, 116–18; Siecienksi, Filioque, 113–15.

15. After they conquered Normandy in France, the Norsemen were sometimes called Normans, and their move from Normandy into England is referred to as the Norman Conquest.

16. It is ironic that the land we call Turkey today had no Turkish peoples in it until the eleventh century. In fact, the Turkish migration and conquest meant that Asia Minor went from being almost 100 percent Christian (and ethnically, mostly Greek) in the year 1000 to being 90 percent Muslim (and ethnically mostly Turkish) by 1500.

17. For the rest of the story, see Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, 2nd ed., Yale Nota Bene (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

18. See Riley-Smith, Crusades, 149–60.

19. See Siecienski, Filioque, 134–38, 152–72.

20. The most significant such instance was the fourteenth-century controversy between Barlaam, a Greek monk trained in Roman circles, and Gregory Palamas, who represented and defended more traditional Greek monastic practices against Barlaam’s Western-influenced innovations. This controversy led to Gregory’s articulation of the essence-energies distinction in describing God, one of the hallmarks of modern Eastern Orthodox theology. See John Meyendorff, introduction to Gregory Palamas: The Triads, Classics of Western Spirituality (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1983), 1–22; Lossky, Mystical Theology, 67–90.