15

New Generations of Protestant Confessions

As we saw in the previous chapter, the magisterial movements of Lutheranism and the Reformed churches shaped the early Reformation, while the more radical movement of the Anabaptists broke away and formed new communities. We also looked at the issues that divided these three branches of Protestantism—the sacraments on the one hand, and the challenges raised against the Reformation by Anabaptists on the other—although all Protestants shared the view that churches must separate from Rome.

In this chapter we cover Protestant confessions written from around 1535 until roughly the 1560s. The Reformers who wrote these second-generation confessions now assumed that there was some theological division between the different Protestant groups. In this second phase of the Reformation, not only did Reformed, Lutheran, and Anabaptist confessions strive more and more to define their camp within the wider Reformation, but there were also confessions written in other cities and countries for the first time (e.g., in England). Our focus in this chapter, then, is how Protestant confessions continued to unify these early Protestant camps internally, expressing their central beliefs, and also how the Protestant faith began to fan out into these new regions.

Catholic apologists always claimed that Protestantism was a religion of rebellion and anarchy. They maintained that justification without works was a gateway to citizens without obedience. In response, Martin Luther was immovable when it came to any discussion of political violence.1 He advocated instead for a position of passive disobedience (refusing evil commands, but never engaging in violent resistance). Luther’s position became more entrenched after the Peasants’ War broke out in 1525, as some used Luther’s protest as grounds for overthrowing the medieval establishment. Luther responded with one of his most vicious tracts: Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants. His rhetoric was inflammatory, calling for the rebellion to be put down with as much haste and ferocity as was necessary. The problem with Luther’s position, however, was that he was himself an outlaw. Lutheran princes and pastors who affiliated with Luther could, at least in theory, be accused of sedition if the empire did not wish to go to the trouble of an excommunication trial. A connection with Luther implied guilt by association.

In the previous chapter we looked at the initial success of the Augsburg Confession (1530), as Charles V cautiously admitted that the Lutheran message was tolerable (although he fumed in private that he could not pull out the roots of heresy). Charles needed to keep the princes of Germany unified against threats from the Ottomans and France, and Melanchthon’s careful wording in that confession made it possible to avoid war between Catholic and Protestant princes. There was also the issue of Luther himself—now a celebrity and hero to Protestants around Europe (even to those who disagreed with his theology), and even a symbol of German pride. Charles knew the story of Jan Hus, whose execution in 1415 had infuriated his compatriots and forever cemented the Hussite rebellion against pope and empire. Charles did not want to make a martyr of Luther.2

The Lutherans, however, were not foolish enough to think that Charles would always have the patience of Job. Thus, the Lutheran princes agitated for a new defensive league—later named the Schmalkaldic League, since it came together at the city of Schmalkalden in 1531. The formation of this league was inherently seditious, at least in principle, since it involved imperial princes and citizens uniting under a potential banner of war.

Martin Luther by Hans Brosamer [Everett Historical/www.shutterstock.com]

The issue that perplexed them was, in fact, Lutheranism—or at least Luther’s teachings on political nonresistance. We have seen that his early position was necessary to avoid anarchy, but now it ruined any chance of forming a league in defense of the Reformation. For his part, Luther recognized the threat of war and knew that the stakes were high: if Charles were to win, he would impose Catholicism in Lutheran lands. So in 1531 Luther changed his position to allow for defensive resistance led by princes in order to repel Catholic armies, although not for outright rebellion and certainly not rebellion by private Christians. Luther argued that if attacked, if Lutheran princes gave the order, it was allowable to take up arms against the empire.3

The other critical issue at this time was that Pope Paul III called a church council to meet in 1536 in Mantua. The Lutheran and Reformed churches felt the need to offer some basis of a dispute, should they be invited. We will look later at the Reformed confession written as a response (the First Helvetic Confession), but for the formation of the Lutheran league, this was an important change of focus. Luther drew up the articles at the behest of John Frederick of Saxony, but while the articles were agreed to at Schmalkalden as part of the formation of the league, the Catholic council never materialized. The articles languished, and so in 1538 Luther published them in order to make public his mature views on all the important Reformation doctrines “if I should die before a council meets.”4 This was, in a sense, his confessional last will and testament.5

Cities of Schmalkalden in Germany and Mantua in Italy [© Baker Publishing Group]

The Schmalkald Articles revealed Luther at his polemical best (or worst, from a Catholic point of view). The balanced language of the Augsburg Confession gave way to rhetoric like that of the early 1520s, as Luther no longer believed that there could be any positive outcome to a church council with Catholics. In his preface, Luther admits that he is exasperated by the constant need to defend the Reformation before his opponents: “I suppose I should reply to everything while I am still alive. But how can I stop all the mouths of the devil?”6 One recent claim even stated that Lutherans had abandoned marriage entirely, and they now “live like cattle” together. Thus, Luther wanted one last confession, in the hope that it might somehow stop the mouths of his critics.

We can set aside the strong language of polemic, but there are several features of the Schmalkald Articles that deserve our attention. The articles are broken up into three main sections, and they open with a simple declaration that Lutherans affirm, like Catholics, the three central creeds: the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed. Because they share these in common, “it is not necessary to treat them at greater length.”7

The second section covers the “office and person and work of Christ,” or the subject of redemption. This middle section rarely pulls any punches and is the most polemical section. The pope is stated to be the antichrist, and the Mass is “nothing else than a human work, even a work of evil scoundrels.”8 Still, this section has one of the more substantial declarations on justification, in that it writes that “faith alone justifies us.” Not only do we rarely see such language from the Reformation, but we should also note how infrequently confessional (or other theological) texts mentioned it in this slogan form. Luther famously added the word “alone” to the text of Romans 3:28 (“one is justified by faith alone”) when he translated it in the 1520s, but rarely did such a phrase thunder in the sources. Here Luther states it explicitly and adds, “Nothing in this article can be given up or compromised . . . on this article rests all that we teach and practice against the pope.”9

Other than covering the typical issues of the Reformation—monasticism, celibacy, and the like—Luther states that the Mass would be the most important issue discussed at any council. The problem arose because, he admits, the Lutheran position is that the Mass is “nothing else than a human work, even a work of evil scoundrels . . . if the mass falls, the papacy falls with it.”10 Papal corruption was a critical issue to raise, but we should notice that Luther here says little of his position and only reports the issues that he holds against the Mass, mainly that it is supported by papal authority.

The third section is by far the most extensive treatment of the issues central to Lutheranism. It opens with a strong defense of the doctrine of original sin, which Luther says is “so deep a corruption that reason cannot understand it.”11 The doctrine of sin, he argues, is vital to understanding the gospel, as it contradicts the teachings of medieval theologians, who stated that the will remained free to do good works, though it was weakened apart from the sacraments. The law must come to teach sinners how wicked they truly were; and on this issue, Luther spells out one of the most important issues for later Lutheran and Reformed debates: the twofold use of the law that was becoming common in the Reformation. First, the law is useful “to restrain sins by threats and fear of punishment.” We can remember the First Use of the Law by the analogy of a bridle: the law is used not for salvation but to restrain humanity in its wickedness. In other words, this use of the law we might today describe as the political use of the law, whereby it is used to buttress civil action against murder, theft, and so forth. Few Christians today speak of biblical law in this light—or they oppose using the Bible in societies that separate religion from politics. In Luther’s day, however, this First Use of the Law was affirmed by all Christians as a rationale for political action against evil.

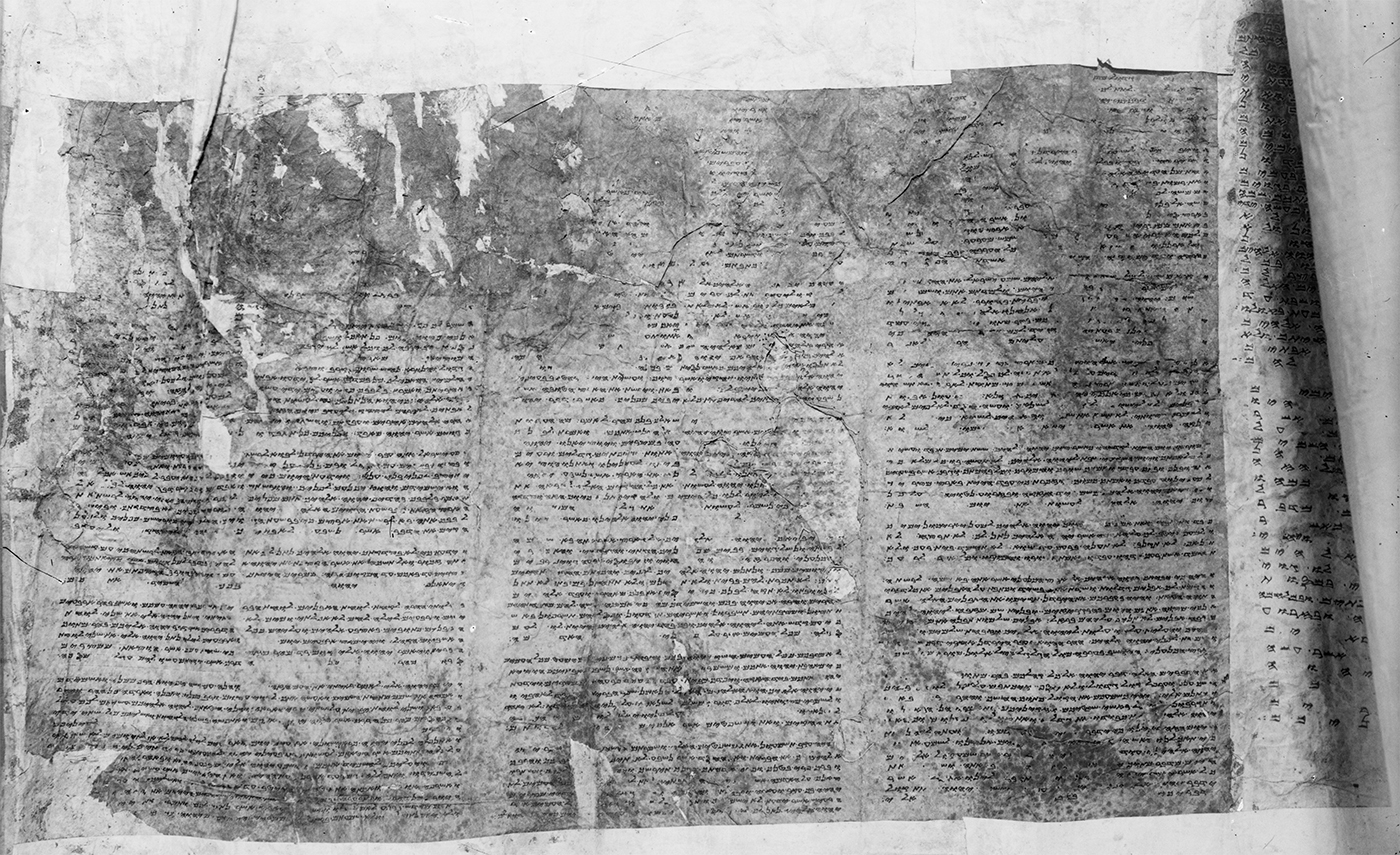

Ancient scroll of Old Testament law. Luther articulated two uses of biblical law. [American Colony (Jerusalem) Photo Dept., Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Luther next goes on to focus on the Second (and weightier) Use of the Law for salvation. “However,” he writes, “the chief function or power of the law is to make original sin manifest and show man to what utter depths his nature has fallen and how corrupt it has become.” If the first use is a bridle, the second use can be understood as a mirror. Luther argues that the law was meant to expose our self-righteousness by holding up the perfect standard. Since we fall short of this standard, we despair in our works and cling to Christ’s work in faith. This process of the law revealing sin, driving us to the cross, Luther explains, is located almost exclusively in the preached Word. This analogy of the mirror is important because it clarifies Luther’s message: he was not opposed to the law per se, but he resisted using the law as a guide for Christian living or good works. Luther’s point in this explanation is to claim that the law itself is holy, although it only reveals the ugliness in us.

Luther does not speak of a category called the Third Use of the Law, but this came into play shortly after his death and sparked debate well into the seventeenth century. The debate over the Third Use of the Law centered on the issue of how the law might be used after conversion: Was it to be used only as an instrument that revealed our guilt (Second Use of the Law), or could it ever be used in a positive sense to guide the life of sanctification (Third Use of the Law)? In other words, should the law be used only to reveal guilt and shame, or could it be appropriated into rules for living?

An analogy for the Third Use of the Law is a flashlight: the law spotlights the path that we should walk. The question was so crucial, in fact, that it received special treatment in the Formula of Concord (1577), which we will examine in chapter 17. But here it should be noted that Luther does not explicitly deal with the question, since the issue was not yet a controversy between Lutheran and Reformed theologians. Almost certainly, Luther would have rejected the notion of any positive, postconversion use of the law. Sanctification, he always stressed, came not from focusing on our righteousness but by grasping the work of Christ each day. Reformed theologians almost unanimously embraced the Third Use of the Law, and so another issue eventually came between them and the Lutherans.

The remainder of the Schmalkald Articles is much like what we have already seen from Luther. The importance of the confession, however, is that Luther wrote it just as his church was coming together as a military faction. The Schmalkaldic League fought mainly skirmish campaigns for several years to expand Lutheran territories and to gain the right to depose Catholic priests. When Luther died in 1546, however, with him died any hesitation from Charles V about ending Lutheranism. Charles was fortunate at this time, too, in that he no longer felt pressed on either side by Ottoman or French forces. He believed that the Schmalkaldic League had provoked war, and so he launched a series of campaigns (known today as the Schmalkaldic War) against the league between 1546 and 1547.12 The Schmalkaldic League, technically, had superior forces and should at least have stood its ground. However, it lacked cohesion—due in large part to having too many voices jockeying for control—and so at the Battle of Mühlberg (1547) Charles conquered the Schmalkaldic League, removing any protection for Lutheran churches.

On May 15, 1548, Charles issued the decree known today as the Augsburg Interim, which was a piecemeal declaration, although it temporarily halted the spread of Lutheranism. By this point, Charles awaited the conclusion of the Council of Trent (to be discussed in the next chapter), before enacting stricter measures. The Augsburg Interim stipulated that all Lutheran churches must restore the seven sacraments, cease preaching on justification by faith, and reinstate all former Catholic practices. As far as Charles was concerned, the Reformation was over.

With Luther gone, the obvious choice to take control was Philip Melanchthon. He had been Luther’s right hand during the Reformation, and, by this stage, no other person had helped form Lutheranism more than Melanchthon. When he received the terms of the Augsburg Interim, however, Melanchthon chose a route that managed only to undermine his credibility with Lutheran pastors and theologians: he embraced the Augsburg Interim in a bid for peace. One can appreciate his flexibility, but Lutheran pastors at the time condemned what seemed a betrayal of the Reformation. Throughout Germany, hundreds of pastors chose prison over submission, and some lost property or family members to violence. As a result, Melanchthon’s acceptance of the Augsburg Interim helped erode any support from Lutherans, allowing other theologians to rise to positions of strength. These issues resulted in the final Lutheran confessional standard, the Book of Concord, which we will look at in chapter 17.

The Spread of German Reformed Confessions

After Huldrych Zwingli’s death, Heinrich Bullinger took over as the lead voice for Zürich. Zwingli had mentored him, and he was learned, patient, and committed to the same theological principles. Bullinger always remembered the struggles that Zürich endured after the failure to achieve unity with Lutheranism, and so he was suspicious of Reformers who continued to seek confessional unity with Wittenberg. Bullinger also strove to expand the horizon of the Reformed community beyond the Swiss cantons. One recent study has noted the astonishing number of letters that Bullinger sent to other Protestant leaders, as well as how frequently other cities asked Bullinger for his opinion on church matters. For the entirety of his career, Bullinger was a senior statesman for Protestantism.13

The need in Zürich was to silence those who saw their future only through the lens of the failures of the Marburg Colloquy. Several Swiss cities, for example, had already embraced the Reformed faith, with some even adhering to Zwingli’s view of the Lord’s Supper. Swiss cities, like modern Switzerland, were shaped by different languages: Zürich, Bern, and others were German-speaking; Geneva and Neuchâtel were French-speaking. The city of Geneva and the surrounding Vaud canton were even under the authority of the Duke of Savoy (on the border of modern Italy and France). The Reformed confessions, therefore, were often based on two needs: on the one hand, they needed to continue the struggle to achieve recognition from the empire; on the other hand, they needed to unite themselves into a unified perspective—separate from Luther, yet still Protestant in message.

For example, when Charles V summoned the Diet of Augsburg and requested that the Lutherans submit a statement of their faith, the major Swiss cities worked feverishly to avoid being frozen out of any decision by Charles. If the Lutherans were granted protection, the Reformed churches wanted protection too. Their efforts produced the Tetrapolitan Confession—named for the four (tetra) cities that composed the assembly: Strasbourg, Konstanz, Memmingen, and Lindau. The confession was almost entirely the work of Martin Bucer (1491–1551), working in collaboration with Wolfgang Capito (1478–1541). Capito served as pastor in the important Swiss city of Basel, and there he had befriended Zwingli while also corresponding with Luther. Capito, therefore, was committed to working with both sides, though he favored the Reformed critique of Luther’s view of the sacraments.

Bucer, however, spent his career working to unite the various sides of Protestantism.14 His passion for unity was personal as much as temperamental, since it was Luther who had converted him. While serving as a Dominican monk, Bucer had attended the Heidelberg Disputation, where he witnessed Luther’s agitation for reform. Within a year Bucer had arranged to have his vows annulled before fleeing to Strasbourg. Bucer, in other words, was both a defender of Reformed theology and forever indebted to Luther for his faith. He also believed that the two sides could eventually agree, given enough time and conversation. For this he was mistrusted and even scorned by leaders from both Lutheran and Reformed camps.

The central issue, of course, was the Eucharist. Bucer did not agree with Luther’s commitment to the physical presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper, but unlike Zwingli, he was not committed to the idea that the bread and wine were only a memorial, which seemed to deny Christ’s presence altogether. Indeed, the word “truly” would be ideal for understanding Bucer’s position: Christ is truly present, truly offered, and truly there. This was not an attempt to play the middle but was instead based on Bucer’s concerns about both sides. He shared Luther’s concern that the language of memorialism locked Christ away in heaven, separated from the sacraments; he also believed that the Zwinglian position would be better if it were strengthened to stress what was in, rather than what was not in, the Lord’s Supper. Over the years, the churches of Strasbourg were frustrated by the Zwinglian position—at one point accusing Zwinglians of having a “Christless Supper”—but in these early days hope remained for Protestant unity. If they strengthened Reformed language on the sacraments, Bucer assumed that it would persuade those in Wittenberg.

The Tetrapolitan Confession, then, offered to the Diet of Augsburg a new Reformed articulation of the sacraments, although Bucer and Capito chose their words carefully. They first framed the struggle for the Reformation by noting that “since about ten years ago”—roughly since the Diet of Worms—“the doctrine of Christ began to be treated with somewhat more certainty and clearness.”15 Catholic teaching in the medieval church, since it focused on works, had confused the issue, so it was evident that the Reformers needed to stress the doctrine of justification without works during the early Reformation. Now the Reformed camp instead wished to underscore that “these things we shall not have men so to understand, as though we place salvation and righteousness in slothful thoughts in the mind, or in faith destitute of love, which they call faith without form.”16 The confession contended that their message was precisely the same as Augustine’s teaching on “faith . . . efficacious though love,” although they stressed that love itself is a gift of the Holy Spirit.

The confession focused next on practices that Protestants had thrown out of their churches: monasticism, mandatory fasting, and other patterns of life that implied the necessity of good works. They had also removed images from the church, because Catholics so abused them and they contravened the biblical teaching on worship. However, unlike Zwingli, the Tetrapolitan Confession did not see a sharp separation between spiritual and physical categories, because “the church lives here in the flesh, though not according to the flesh.”17 Perhaps the most striking feature of the confession, however, is its statement on the Lord’s Supper that offered a closer relationship between physical and spiritual eating. It admits that “adversaries proclaim that our men change Christ’s words [to mean] that nothing save mere bread and mere wine is administered in our suppers.” In language that must have come from Bucer, the confession stresses instead that God “deigns to give his true body and true blood to be truly eaten and drunk.”18

In the end, the Tetrapolitan Confession lasted only a year. It was never seriously considered (or even read) at Augsburg, and so it failed at its purpose immediately. To make matters worse, the language of the confession was rather dense—a feature of Bucer’s writings in general—and at times the meaning was not clear.

Bucer and other Reformed leaders had more goals, however, and they continued to seek a stronger footing for Reformed theology. The number of Reformed confessions continued to swell, and in the early 1530s, two were particularly noteworthy: the First Confession of Basel (1534) and the First Helvetic Confession (1536). Today, these two confessions can create confusion—along with the more widely adopted Second Helvetic Confession—because all three are confessions from Basel, though two are titled the “first” confession and two include the word “Helvetic.” But the Basel confession was written for needs different from the Helvetic confessions, and all three had different sets of authors. These three confessions were an important pivot for Reformed churches.

The First Confession of Basel was written by Oswald Myconius (1488–1552). He based his text on a shorter confession written by Johannes Oecolampadius, a leading early Reformer who had succumbed to the plague in 1531. The occasion for this confession was the slow pace of reform in the city of Basel, which had officially embraced the Reformation as early as 1524 but did not outlaw the Mass until 1529. Some in the city doubted whether the Reformation would last. Tensions in the city also erupted in one of the most violent riots of the Reformation, as an angry mob destroyed many of the images and statues in Basel’s churches. Oecolampadius and Myconius were tireless in their efforts to restore order and further reform, and they were inspired by the work of Zwingli in Zürich. They feared Anabaptist fervor, and now that the city was willing to embrace the Reformation, they needed a simple confession to pass the city council. The confession was offered and accepted on January 21, 1534.

The First Confession of Basel has twelve basic affirmations, all relatively straightforward. One unique feature is the explicit connection of the doctrine of election to the doctrine of God—a standard feature of later Reformed scholastic theology, but not typical at this point, since most early Reformers discussed election only under the rubric of salvation. After an orthodox statement about the Trinity and God’s creation of the world, the article states that God chose people to salvation before he created the world. Under this rubric, the act of God’s election appeared to rest on creation itself, independent of the fall of humankind. In earlier confessions, by contrast, the topic was discussed under the subjects of the freedom of the will and original sin, which focused only on the question of how one came to faith. As we will see in chapter 17, these issues were raised again during the Reformed-versus-Arminian struggle in the seventeenth century.

Of course, as with many Reformed confessions around this time, the central focus is on the sacraments. The authors admit that the critical issue is a proper understanding of Christology, since it is the foundational doctrine for understanding the Lord’s Supper. Like Zwingli, the confession states that Christ is “united with human nature in one person” but that “he ascended into heaven with body and soul where he sits at the right hand of God.”19 We should note that, by this point in the Reformation, the comment that Christ was seated at God’s right hand was a bedrock assumption in Reformed churches. This language, of course, is not about heaven, or even about Christ’s authority; it is a statement to identify that Christ is located somewhere (at the Father’s right hand) and that somewhere has a physical space, making it impossible that his finite body can come to be physically in the Lord’s Supper. The confession appeals to this doctrine twice, both in the context of the sacraments, and concludes, “Water remains truly water, so also does the bread and wine remain bread and wine in the Lord’s supper, in which the true body and blood of Christ is portrayed and offered to us. . . . However, we do not enclose in the bread and wine of the Lord the natural, true, and essential body of Christ.”20

The First Helvetic Confession was drawn up by Bullinger and Leo Jud after Pope Paul III had called for a church council. The context, then, was not an effort to begin the Reformation but to send an official statement of faith to the long-awaited Catholic council. The opportunity to give a single confession of the Reformed faith, however, proved tempting, and so on January 20, 1536, Bucer and Capito (as well as representatives from Bern) joined the meetings—making this the first attempt to unite the largest and most important cities of the Reformed movement into one confessional entity. Indeed, the opening statement of the confession described its framers as “churches banded together in a confederacy.”21

The most crucial factors at the First Helvetic Confession meetings were the roles that Bucer and Capito played in the language of the confession—roles that eventually led to the confession’s demise. Bucer, as we have seen, was concerned about the reputation of the Reformed faith. The Tetrapolitan Confession had done little to repair the reputation of Reformed churches among Lutherans, and so Bucer’s presence was crucial. Eyewitness accounts after the session, in fact, admitted that both Bucer and Capito stressed the need for broader language about the orthodoxy of Reformed theology, as well as more exact language on the sacraments, so as not to give credence to the opinion that Charles should deal only with Lutherans.

The confession opens with a statement on both the authority and the interpretation of the Scriptures. The Bible’s interpretation “ought to be sought out of itself, so that it is to be its own interpreter, guided by the rule of love and faith”—a rejection of the Anabaptist belief that the Spirit gives guidance when one is personally reading the Bible. The article goes on to affirm patristic writings as perhaps an even greater source than some admitted previously in Reformed circles: “From this interpretation [of faith and love], so far as the holy fathers have not departed from it, not only do we receive them as interpreters of the Scripture, but we honor them as chosen instruments of God.”22 The language is restrained, describing the fathers as mere instruments and not authorities in themselves, but it nevertheless casts Reformed theology as faithful to early creedal orthodoxy.

A few issues besides the sacraments are notable in the First Helvetic Confession. Perhaps the most striking addition—one that had not been mentioned in a Reformed confession previously—is the article on free will, which begins by affirming that humans as the image of God have a free will: “We ascribe freedom of choice to man because we find in ourselves that we do good and evil knowingly and deliberately.” This concept is important to grasp if we are to understand later debates on free will between Calvinists and Arminians. When it came to basic free choice outside salvation, the Reformed camp always affirmed this as part of its teaching.23 However, when looking at the central issue of free will—the question of our ability to choose God by our power—the framers of the confession (like all early Protestants) denied that we had such free will after the fall: “to be sure, we are able to do evil willingly, but we are not able to embrace and follow good (except as we are illuminated by the grace of Christ and moved by the Holy Spirit).”24 The issue of free will, in other words, depends on what one has in mind when one affirms or denies human freedom. If the question is about our choices day by day, especially our choice to sin, then the First Helvetic Confession confirms this freedom. When it comes to our choice to place our faith in Christ, however, the framers of the confession denied human capacity to do so and saw faith as a gift of regeneration given by the Holy Spirit. In chapter 17 we will see the importance that this issue had subsequently.

Naturally, the confession spends most of its space explaining the nature of the Lord’s Supper (as well as baptism), focused as always on the nature of Christ’s incarnation. The confession chose the most forceful language to date of any Reformed confession, stating that sacraments are “significant, holy signs of sublime, secret things.”25 The article affirms that the bread and wine are signs—just as Zwingli and Bullinger always stressed—but it goes on to say that “they are not bare signs, but they are composed of the signs and substance together.” The choice to use the word “substance”—a key term in medieval teaching on the Eucharist—was meant to rule out a caricature of Zwingli’s teaching on the sacraments. In a deft balancing act between Bucer and Bullinger, the framers conclude,

In regard to the Lord’s Supper we hold, therefore, that in it the Lord truly offers His body and His blood. . . . We do not believe that the body and blood of the Lord is naturally united with the bread and wine or that they are spatially enclosed within them, but that according to the institution of the Lord the bread and wine are highly significant, holy, true signs by which the true communion of His body and blood is administered and offered to believers.26

The confession then concludes with a plea that Reformed churches no longer be condemned for devaluing the sacraments.

The First Helvetic Confession was the most unified of the early Reformed confessions not only because so many Reformed leaders took part in drafting it but also because it signaled a new effort among some leaders to distance themselves from Zwingli. Bullinger later bristled at the notion that Zwingli’s teachings were inferior, and he contended as well that he didn’t knowingly sacrifice anything when Bucer and Capito requested this new language. So the First Helvetic Confession was plagued by the fact that Bucer seemed afterward to have been less than clear about his objectives. Bullinger had intended only to explain the Zwinglian position, but some viewed the confession as a departure from Marburg. As a result, the relationship between Bucer and Bullinger was poisoned.

One more confession arose because of Bucer’s efforts to unite Lutheran and Reformed sides: the Wittenberg Concord of 1536. As one scholar noted, Bullinger by this point joked that the Latin origin of Bucer’s name must mean “to vacillate.”27 Following on the heels of the First Confession of Basel, Bucer and Capito attempted to write a confession with those in Wittenberg. Bucer felt optimistic after the result of Basel, but he may have felt that the issue just needed a Reformed voice to start the conversation. Surprisingly, he managed to get Luther and Melanchthon on board, and Melanchthon drafted a set of articles for their meeting. Both sides gave some ground. The Reformed party agreed not to use the offending Zwinglian word “memorial,” though they minced no words about “the Zwinglian teachers” who strove “to introduce their error.”28 Luther as well briefly allowed that the presence of Christ was offered “with the bread and wine,” and both sides rested the confession on the language that Christ’s body and blood were “truly” offered.29

The Wittenberg Concord perhaps aspired to too much, especially when the unity between Lutherans and Reformed churches was only on paper. Bucer and Capito spoke for none of the Reformed churches the way Luther and Melanchthon could speak for the Lutherans. Once the confession was finished, the only party that appreciated it was the Lutheran faction. Some German Reformed cities rejected it, and nearly all Swiss churches scoffed at its language. An ironic twist was that Bucer’s ministry in Strasbourg naturally led the city to embrace the Wittenberg Concord—although pastors in the city later began to interpret it in a Lutheran manner. By 1549, the situation was such that Bucer was no longer welcome there, and he accepted Thomas Cranmer’s offer to teach in Cambridge. Bucer died there in 1555.

Rise of French Reformed Leaders

The legend of John Calvin (1509–64) has grown with the telling. Historians regularly find it necessary to remind students of Calvin’s actual role in the Reformation, which was not as the founder of the Reformed faith, nor even the dominant influence on early Reformed churches, at least in his lifetime. Instead, Calvin was a second-generation Reformer, whose reputation was at first minimal in some Swiss regions, but he increased in stature by the end of his life. The publication and expansion of the Institutes, of course, made Calvin one of the most influential Reformers on future generations. However, today there is a host of dubious assumptions about Calvin and Calvinism, predominantly in the English-speaking world, and especially after the Reformed-versus-Arminian fights in the seventeenth century.

John Calvin [Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons]

This is not to say that Calvin was unimportant, but that his importance was not as the sole founder of the Reformed movement. Instead, he was one of the many Reformed leaders to shape the future of their confessional identity. Indeed, perhaps the most pivotal role that Calvin played in his lifetime was his participation in talks to unite the Zwinglian Reformation to the other Reformed cities, first in the Swiss cantons and then in other parts of Europe.

The German Reformed communities sprouted quickly and since 1531 had spread to capture new cities such as Basel and Bern. The French-speaking Swiss cantons, however, had been marginalized during these years, due to the barriers of language and culture as well as the vagaries of local political authority. In the early 1530s, this all began to change. The Vaud canton managed to free itself from the authority of the House of Savoy, opening the door to reform in these cities. Bern played a key role in this and often initiated the reform efforts in nearby French churches. Indeed, in 1536, Bern marched a small army to the city of Geneva and annexed it. Some in the city were happy to unite with Bern, and some even hoped to see reform.30

Cities of the Swiss Reformation [© Baker Publishing Group]

Bern needed French-speaking leaders to bring the Reformation to these cities. To do so, the city relied on two men: Pierre Viret (1511–71) and William Farel (1489–1565).31 Both had a reputation for being fierce in their convictions—Viret was once almost stabbed to death by a Catholic priest—and not a few times both were blamed for problems stemming from their being too severe with city officials. Still, their German-speaking counterparts in Bern were willing to tolerate these problems because Farel and Viret had successfully brought the Reformation to both Neuchâtel and Lausanne in the early 1530s. The relative isolation of Viret and Farel, though, explains why they were eager to recruit the young John Calvin.

As the Reformation grew in these French-Swiss cities, there arose the need to draft their own Protestant confession. Like Zürich, Basel, and Bern, they needed this so that cities could ratify their conversion to Protestantism; so in 1536, the first of these confessions was drafted, the Lausanne Articles. The meeting was led by Farel and Viret, though records tell us that Calvin attended the session and argued for a few points. The publication of the first edition of the Institutes that same year provided Calvin some measure of authority in the sessions.

Calvin went on to see Farel again when the young Reformer stopped off in Geneva, and with enough arm-twisting (Farel threatened divine condemnation if Calvin were to abandon them and lead the French-Swiss Reformation alone), Farel convinced Calvin to stay. The relationship with city officials quickly soured, due in large part to Farel’s and Calvin’s insistence on using their own confessional standard. The problem was that Bern had annexed the city and already ordered Geneva—and Farel and Calvin—to abide by the Bernese confession. Historians have never fully understood why, but the two French Reformers decided to make a stand by drafting their own text. When city leaders balked, Calvin and Farel took the radical step of barring these men from Communion, effectively excommunicating them without a hearing. Calvin and Farel were given just a few days to leave the city or face arrest.

This painful moment in Calvin’s life ultimately thrust him into the ongoing confessional struggle within the Reformed community. He made his way to Strasbourg, where Bucer nursed the wound to Calvin’s pride and managed to smooth things over with Bern. This was not an easy task. The delicate issues in Geneva made it seem that Farel and Calvin had spoiled the Reformation before it had begun, but Bucer knew that the primary problem was that Farel and Calvin spurred one another into rash decisions. The two were now separated, and Calvin was given a home, sharing a garden with the Bucer household. Bucer even managed to find a wife for Calvin. When he returned to Geneva, Calvin was the same principled campaigner for reform, but he was not the brash man of his early years.

The proximity of Calvin to Bucer was crucial, since we have already noted the increasingly strained relationship between Bullinger and Bucer. While the two never publicly condemned each other, Bullinger grew wary of Bucer’s efforts to build bridges with Lutherans. Although ecumenical in motive, these overtures revealed a flaw in Bucer’s theology. Many now recognized Calvin’s skill as a writer and defender of the Reformed perspective, especially since he had published the Institutes. But would Calvin be a figure like Bucer, or would he find common ground with Zürich?

The answer to this question came in the 1540s after Calvin had returned to Geneva and established himself there as the leading voice in the French-Swiss church. By 1549, it was clear that Zürich and Geneva would need to spearhead a statement of unity on the sacraments. The dark cloud hanging over the Zwinglian view was not bad enough to ruin their churches, but the Reformed faith needed to speak with one voice, especially now that other cities and countries were looking to the Swiss for theological leadership. Bullinger’s views had also matured. He retained many of the essential points that Zwingli held on Christ’s two natures, his sitting at the right hand of the Father, and the need for the presence of the Holy Spirit. But he had also found it wise to emphasize more the positive value of the sacraments, even to the point of asserting that Christ was truly there for our nourishment.

Calvin and Bullinger exchanged letters for some time until November 1548, when Bullinger sent a list of twenty-four articles that could form the basis of an agreement. Calvin then traveled with Farel to Zürich in May 1549—now with twenty articles that Calvin had recently used to argue his case in Bern. The final document, the Zürich Consensus, was a fascinating work of harmonization.32 The agreement was ratified eventually in Lausanne, Basel, and Bern, an act that drew together for the first time the entire Swiss region into a united Reformed movement. Still, it should be noted that consensus confessions such as this succeeded when they allowed both sides to retain their unique views—and the Zürich Consensus did just this. Zürich still leaned more heavily toward Zwinglianism, while Calvin would always stress a view of real presence closer to that of Bucer. But the threat of theological war between the two—or an equally frosty relationship between Calvin and Bullinger—was now gone.

The Zürich Consensus offers first a new assessment of the sacraments, calling them the “appendixes to the gospel”;33 that is, they are not the focus of Christian devotion but its support. The framers stress that the real fruit of salvation comes by being united to Christ, but without the Zwinglian predilection to distinguish physical and spiritual benefits. The articles then go on to highlight the ongoing role of Christ as our High Priest, adding that he pours life into us by his Spirit and so unites us to his resurrection as to bring about all good works. This “spiritual communion,” they argue, is primarily focused on our union with Christ.34

The agreement next describes the sacrament not merely as an oath (as Zwingli had), but as “marks and badges of Christian profession,” which create a different effect by taking the focus away from the believer. The sacraments “incite us to thanksgiving and exercises of faith.”35 And then they add a delicately worded explanation of how this is to be understood: “For although they signify nothing that is not announced by the Word, yet it is a great benefit that there are cast before our eyes, as it were, living pictures which influence our senses in a deeper way, as if leading us up to the thing itself. . . . It is also a great benefit that what God has pronounced with his mouth, is confirmed and ratified as if by seals.” This was a striking statement, retaining Bullinger’s desire to avoid confusing the bread and wine with the actual benefit of the Spirit, while adding newer language that drew the two sides together. The suggestive notion of the elements as “living pictures” or the ratification of something sealed in us also balances Christ’s real presence without making the elements themselves the main focus. Article 22 then goes on to “reject therefore those ridiculous interpreters who insist on what they call the precise literal sense of the solemn words of the supper—This is my body, this is my blood.”36 This statement meant that not only were the two sides united; they also found an agreement so that the Lutherans were no longer the focus of their energy.

One final confession we should consider is the French Confession of 1559 (later ratified officially in 1571),37 since it was the first Protestant statement for the French Reformed churches. It was also the only lengthy confession on the substance of the Reformation that John Calvin played a significant role in drafting. The authors based the confession on an earlier document beseeching the French king to halt persecution in that country. Persecution continued nevertheless, but now that the French-Swiss had begun to expand their influence internationally, the French requested aid from Calvin and Theodore Beza (1519–1605) in drafting a complete confession. The eight articles from the original text were converted into thirty-five, and the result was one of the most mature confessions of the first two generations of the Reformation, especially in its carefully balanced language and attention to detail. Calvin was likely the hand behind the smooth style, since the text bears a resemblance to his tight, humanist prose. The way each article builds on the previous one and anticipates the next is exceptional. This type of arrangement had been used in some confessions, but not always consistently. The maturity of the French Confession does not mean that there are no questions raised from its language; but this was a confession that was beginning to describe not just a set of positions but a fully orbed theology with a confessional identity.

The framers of the French Confession were careful to affirm the Reformed line on the sacraments, but in a fashion that was becoming the Genevan perspective on the subject—namely, they did not take the Zwinglian position, but neither did they abhor it; they saw fruit in the work of Bucer to create a bridge to Lutheranism, but they didn’t insist on it. The confession opens with a simple statement on the nature and attributes of God. Here the stress is laid on the unity of God as a “sole and simple essence,” rather than beginning with a trinitarian formula of any kind. The second and third articles then address the issue of how we come to know this one God: through the order of creation (article 2) and finally through the sixty-six books of the Bible, which are listed by name (article 3). The confession also stresses that other authorities are inferior to the Scriptures, but it affirms the three official ancient creeds “because they are agreeable to the word of God.”38

The confession then takes an unusual tactic in that it gets to trinitarian language only after these other matters are clarified. Perhaps because of this, some phrases suggest a less-than-traditional approach to trinitarian orthodoxy. As we saw in chapters 4 and 7, the early church primarily approached the subject of God by focusing on persons rather than essence. The French Confession places the stress first on the oneness of God, “this one and simple divine being.” The confession continues:

The Father . . . the first cause in order, and the beginning of all things: the Son, his wisdom and everlasting Word; the Holy Ghost, his virtue, power, and efficacy. The Son begotten of the Father from everlasting, the Holy Ghost from everlasting proceeding from the Father and the Son; the three persons not confused, but distinct, and yet not divided, but of one and the same essence, eternity, power, and equality.39

This language certainly is within the bounds of orthodoxy, and there is nothing here that overtly denies the Nicene Creed. But the confession is suggestive of the popular way in which Western and, by extension, Protestant theology has laid stress on the one essence before discussion of the three persons and has relegated any discussion of the persons to the role each person plays in salvation. The confession, therefore, refers to God in the next article as “three coworking persons” in the act of creation. The language of the Father as the “first cause” demonstrates the use of Aristotelian categories to describe God, which had been present in the early church and became increasingly common after the thirteenth century.

The most detailed and developed discussion in the French Confession, however, relates to the sacraments. As with other Reformed confessions, the treatment of the sacraments depends on an initial affirmation of Christology. In Jesus Christ, the framers write, “[Christ’s] two natures are inseparably joined and united, and yet nevertheless in such a manner that each nature retains its distinct properties.” In other words, there is a set of attributes that pertains to the different natures (e.g., omnipotence to the divine, hunger to the humanity), but these are united first and primarily in the person of Christ. The confession stresses the need for a distinction without separating the two: “the human nature remained finite . . . and also Jesus Christ when he arose from the dead gave immortality unto his body, yet he never deprived it of the verity of its [human] nature.”40 From this basis, the confession argues a consistent line about both sacraments: they, too, must be distinguished between the physical and spiritual natures. And yet the confession can make bold claims that the Eucharist “feeds and nourishes us truly with flesh and blood” and is not merely “shadows and smoke.”41 Only after this strong affirmation does the confession clarify that “he is now in heaven, and will remain there til he comes to judge the world,” and so it is “by the secret and incomprehensible virtue of his Spirit [that] he nourishes and quickens us with the substance of his body and blood.”

But we say this is done in a spiritual manner; nor do we hereby substitute in the place of effect and truth an idle fancy or conceit of our own, but rather because this mystery of our union with Christ is so high a thing, it surmounts all our senses . . . in short, because it is celestial, therefore, it cannot be apprehended but by faith.42

The confession thus incorporates some of the newer Reformed language about the Lord’s Supper. In other words, its framers assert that a Zwinglian denial of the spiritual value of the bread and wine—although the French admitted that they were symbols—would be akin to denigrating the humanity of Christ in an effort to elevate his divinity. Rather, the French Confession stresses that we can speak of separation (bread and wine versus the presence of the Holy Spirit), but the language here affirms that we do take his flesh and body, and only then goes on to distinguish what the eating means.

The French Confession was an important step toward a more developed set of Reformed confessions, which we will look at in chapter 17. But the confession itself was relatively marginalized, due in large part to the resistance of the French crown to the Reformation. The confession was edited and affirmed at the National Synod at La Rochelle in 1571.

The Start of the English Reformation

If one were to search for the least likely country to embrace the Reformation, England would be at the top of the list. Almost immediately, Henry VIII responded to the Reformation with a mixture of anger and condemnation.43 He had in his service two men who ensured that Lutheran seeds had no chance to grow: John Fisher (1469–1535) and Thomas More (1478–1535).44 Fisher served from within the church, examining clergy and writing books against Luther’s theology, while More served from the court for the same purpose. Both were learned men, known for their piety, and neither saw any value in the Protestant faith. The church corruptions so common in some European countries—sexual license and lavish spending—did not occur with much frequency in England. It was not easy, then, to point to overwhelming and obvious examples of the need for reform. Henry and his Catholic supporters, therefore, were a bulwark against the encroachment of Lutheranism into England. Indeed, historians can count on one hand the number of people in England who sympathized with Protestant theology in the early years. If this would grow into Protestant England, it was at this stage only a mustard seed.

The problem that led to the formation of the English Protestant church was a dynastic crisis for Henry VIII. His family was the Tudor dynasty, which had taken the throne by force when Henry’s father had defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. Henry VIII had been second in line for the throne—his older brother, Arthur, had died young in 1502, leaving behind his Spanish wife, Catherine of Aragon.45 Spain was among the most powerful countries in Europe, and the new Tudor dynasty was not about to send Catherine home. So papal dispensations were secured, allowing Henry to marry Catherine. Such a marriage was forbidden in canon law, but for situations where hereditary monarchies were at stake, the pope normally accommodated, and did so in this case.

As Henry struggled against Lutheranism in England, he soon grew suspicious that something was wrong. By the mid-1520s, Catherine had suffered numerous miscarriages, provoking in Henry the fear that God was punishing him. In the end, he decided that the trouble lay in his marriage to Catherine—and he found Leviticus 18 to be a clear judgment against sexual relations with one’s sister-in-law. Henry soon convinced himself that the pope should never have given a dispensation for the marriage. Indeed, historians have pointed out that, of all the options available, Henry chose the most difficult: the claim that the pope had no authority to dispense with the Levitical law.

Henry went on to marry a total of six wives, but this was not because of the king’s libido. Nor was he merely stamping his foot to get his way. If Henry were to die without an heir, the Tudor house would likely fall, or at least England would plunge into civil war. Henry used every resource at his disposal to get an answer from Rome. After the pope used stall tactics and then refused to render a verdict in the matter, Henry was embarrassed enough to launch an attack on the church itself. To show an example to others, he also executed his two advisers in the fight against Protestantism—Fisher and More—since both opposed the annulment of his marriage to Catherine. Henry also had the entire English clergy accused of sedition (using an obscure fourteenth-century statute forbidding any petition to foreign authorities).46 And, finally, he fell in love with Anne Boleyn—a woman known to identify with some Protestant teachings, and a shrewd woman who refused Henry’s advances without a commitment to marriage. So in 1534, blameless only in his own mind, Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England.

Despite his protest over Roman authority, Henry was overall a poor Protestant. True, several of his actions could have suggested he was inching toward evangelical faith. He attacked the monasteries in 1536, he outlawed many traditional practices, and he even allowed known evangelicals to serve under him. Thomas Cromwell (1485–1540) and Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556), both Protestant by the time of Henry’s divorce, learned how to move Henry toward new ideas that favored evangelical opinion, such as the publication in 1549 of the first official English translation of the Bible (the King’s Bible).47 But no one ever managed to convince Henry of anything like justification by faith, married clergy, or removal of the veneration of saints. On these and other issues, Henry consistently supported traditional medieval views, though after 1534 he denied the very papal authority needed to justify these practices. As one contemporary argued, Henry VIII seemed in effect to be throwing a man from a tower and ordering him to stop halfway down.

Portrait of Thomas Cranmer by Gerlach Flicke [Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Others in England, such as Cranmer, had moved all the way down from the tower. In the early days of the Reformation, Cranmer would have sided with Henry VIII and the Catholic leaders, if more as a humanist than merely a conservative. But he was critical of the Reformation, finding Luther’s message to be obviously heretical—and scholars have discovered his copy of a book by Luther, in the margins of which Cranmer scrawled his angry responses. By the time Henry’s troubles with the pope began, however, Cranmer had moved irrevocably into the Protestant faith, far beyond Henry’s attempts to remain Catholic without a pope. Swiss Reformer Simon Grynaeus visited from Basel in 1531, and he and Cranmer struck up a friendship. By this point, if not well before, Cranmer had sided with the Lutheran message of faith. The following year, while on official duty in Europe, Cranmer met Lutheran pastor and theologian Andreas Osiander (1498–1552), and he took the radical step of marrying his niece. In his mind, and now in his bed, Cranmer had thrown in with Luther.48

Once back in England, Cranmer chose the path of accommodation and patience rather than protest and martyrdom. This feature of his life made Cranmer one of the more curious figures of the Reformation: serving like Daniel in the court of a hostile king, who with the right strokes to his ego might be led to agree with reform measures, or, just as quickly, could order his adviser’s execution.49 The populace, too, was relatively unaccepting of even Henry’s stance on papal authority, since there arose a serious rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace (1536–37), which strove to restore everything about the traditional church, including obedience to Rome. Cranmer worked slowly and haltingly under Henry, though scholars are now aware that his hesitation was based not on conservative theology but on the need to survive.

This tense relationship between Henry and his court—some gritted their teeth against reform while others encouraged it—created the context for the first confession of the new Anglican church.50 This was the Act of Ten Articles (1536), drafted by those in the court, though Henry had a heavy hand in editing the last version. The theology of this confession, however, was unique in the history of the Reformation (or ever since). The articles stitch together a variety of themes, both Catholic and Protestant, to create a mismatched identity. Some elements have an echo of Protestantism, such as the opening words that affirm the Scriptures and three primary creeds (Apostles, Nicene, and Athanasian) as the basis for all doctrine. Other articles, though, continue to support doctrines found in none of these ancient sources, since the pope had promulgated them later by his authority.

For example, the Act of Ten Articles allows for only three sacraments: baptism, Eucharist, and penance. Baptism is affirmed in a traditional sense as an action necessary for the infant. Still, in opposition to Luther, the next article states that baptism is regenerative and washes away original sin. Lutheran confessions, of course, mention that baptism is the source of faith—either then or later in the infant’s life—but all Protestant confessions state categorically that original sin remains. The Eucharist, too, is said to be the physical body and blood of Christ, although there is neither an appeal to transubstantiation nor a Lutheran understanding of Christology, only a mere affirmation of this position. The third sacrament is the most peculiar, as it explicitly continues most of Catholic practice. Contrition, confession, and satisfaction—the Act of Ten Articles requires each of these practices in the English church. Since confession and penance were the material cause of Luther’s reformation, it is hard to see in these articles any trajectory toward Protestantism.

The Act of Ten Articles was perhaps the greatest example of Henry’s reformation. When he died in 1547, however, the stage was set for England to leap aggressively in a Protestant direction. For all of Henry’s desire for traditional piety, he seems to have ignored the education of the heir he had worked so hard to produce, Edward VI. The boy king—as he became known—was educated by Protestant humanists, who saw to it that Edward would embrace the essentials of the Protestant message. Edward was only nine when crowned, making him a minor and unable to rule directly over England until the age of eighteen. As a result, evangelicals in court coordinated a victory in Henry’s last hours, ensuring that the legislative board that would govern England for Edward would be composed entirely of Protestants, including Cranmer.

In 1547, then, England entered one of its most volatile phases during the Reformation. It would not be an overstatement to say that when Edward took the throne, England was still a Catholic nation, now run by a Protestant regime.51 There was also the issue of what authority a governing board had when the king was still a minor. Henry had envisioned the board’s role as only to keep the country running, but the governors of England saw an opportunity for reform, and they embraced it.

The reform efforts were centered especially on the subject of worship. Henry VIII had attacked the wealthiest monasteries, suspecting rightly that these were the central places that could resist the king and inspire Catholic loyalty among the people. Those who accepted the Royal Supremacy, however, remained until Edward’s reign, and the evangelical leaders had them removed. All public places of Catholic worship—not churches, but places such as votaries and other shrines—were taken down. Cranmer also issued two editions of the Book of Common Prayer (in 1549 and 1555), the first designed to introduce Protestant worship to England, the second going further in its language. The new Anglican form of worship now had only two sacraments, a clear statement of justification by faith, and no liturgical language that might point Christians to either their own works or the veneration of the saints. In perhaps an indication of the public commitment to the Catholic faith, there were two riots by angry laity in 1549.

If the English church had a liturgy that expressed Protestantism, it also needed a confession. So, in June 1553, a royal mandate was issued that commanded use of the Forty-Two Articles in England. They were the work of Cranmer, and their message is overwhelmingly Protestant, although they take no noticeable side in the Lutheran or Reformed debate on the sacraments. Like many Protestant confessions, the articles begin by listing the commitment to creedal orthodoxy. The articles, therefore, affirm the Trinity and Christology. Next, they made it clear that the Bible alone is the source of doctrine, though in the next article they affirm the three creeds because their contents are confirmed in the Scriptures. Regarding other Catholic beliefs, the articles state that belief in purgatory, enforcing celibacy for priests, and basing church decisions on the authority of church councils are rejected by the Anglican faith.

The articles then cover the usual topics of Protestantism, affirming the ongoing nature of original sin, that justification is by faith, and that good works (before or after conversion) should not be the basis for assurance. On free will, the confession takes the same position as Lutheran and Reformed confessions, in denying free will to choose God by our efforts and by affirming that salvation is due to God’s eternal election of sinners (predestination). One of the more striking views of the Forty-Two Articles is on the Lord’s Supper, which it interprets in a Reformed way, similar to the views held by Bucer, Calvin, and others who were non-Zwinglian. The bread and wine are said to be “not only badges and tokens” but “certain sure witnesses, and effectual signs of grace.” As we have argued in this chapter, this was a common second-generation Reformed position and not as close to Catholicism as the Lutheran position. There is no focus on the physical eating of Christ’s body and blood, but rather the article states that God uses the Lord’s Supper to “work invisibly in us.”52 To emphasize this view, the article adds that the bread and wine should never be gazed at or lifted up in such a way as to be regarded superstitiously.

The Forty-Two Articles were a crucial step for Anglicanism, but not during Edward VI’s reign. The boy king died within a month of the royal mandate, and he was succeeded by his half-sister, Mary Tudor, a devout Catholic. Mary was the daughter of Catherine of Aragon—tossed aside by Henry, then reinstated in the royal line behind Edward.53 Mary viewed her mother’s struggle to save her marriage to Henry and her death while Henry was married to Anne Boleyn as the fight of a martyr. Mary Tudor, therefore, quickly overturned the mandate for the Forty-Two Articles, leaving them to be reintroduced only later in the sixteenth century when Elizabeth I came to the throne.

It is important to understand where Anglicanism fit within the wider Reformation landscape. The major issue was deciding which phase of the English Reformation to biopsy, and which voice, which text, would become the leading example of Anglican identity. None of these questions were decided in the sixteenth century—if they are even decided today—but for each person leading the Edwardine reformation, the goal was always to embrace Protestantism without necessarily embracing the antagonism between Wittenberg and Zürich.54 Far from seeking a midpoint between Catholic and evangelical, men such as Cranmer wished to stand as a middle way between Luther and Zwingli.55

Later Anabaptist Confessions

We round out this chapter by looking at a few Anabaptist confessions from the later Reformation. There are only a handful of texts from this period, due in large part to the persecution of Anabaptists throughout Europe. The radical communities that might have drafted confessions, therefore, were often fighting merely to survive. Many fled to safer lands, such as those in the eastern part of Europe. The Anabaptist confessions that we will consider come primarily from these regions.

As we have seen, the radical impulse that shaped all Anabaptist communities did not result in their sharing the same theological outlook. Some certainly were Protestant on almost every major issue, especially the issues of scriptural authority and justification by faith. Others, however, were more suspicious of traditional creedal orthodoxy because they believed that these creeds emerged only after the papacy had corrupted the church. If the church had come to adopt erroneous views about baptism and political power, could it not have come to spurious views of Christology and the Trinity as well?

We can see this radical doubt about the ancient creeds in the teachings of Laelius Sozzini (1525–62), who was considered to be the founder of the heresy of Socinianism.56 Sozzini, born in Siena and the son of a famous lawyer who played a role in Henry VIII’s request for an annulment, eventually moved to the Swiss regions and immersed himself in the Reformed movement. The reputation he gained was mixed, as some found him a warm companion and others considered him a pest. Sozzini continually raised doubts about creedal orthodoxy. Although some still trusted him, Calvin and others had doubts about his opinions. A few years later, he sent Calvin several questions that seemed to indicate that he now openly doubted the Trinity and the Chalcedonian Definition. Bullinger, therefore, intervened and asked Sozzini to draft a personal confession on these issues. The result was Sozzini’s Confession of Faith in 1555.

The text is concise and not based on any articles or declarations—at least not the kind found in most confessions. Sozzini’s language, while confessing a desire for charity, is nevertheless laced with a degree of antagonism (perhaps driven by his frustration at having to write a confession in the first place). He opens the confession admitting that as a child he had learned the Apostles’ Creed, and he acknowledges that it is ancient and used by all Christians. “But I have lately read others also,” he continues, referring to the Nicene Creed, “and attribute all the honor I can and ought to.” He then states that he recognizes “the terms Trinity, persons, hypostasis, consubstantiality, union, distinction, and others of the kind are not recent inventions, but have been in use for the last thirteen hundred years.” The point, Sozzini asks, is whether these terms are necessary for all Christians as an issue of salvation, or whether they served a purpose only in the early church (only “necessary for the fathers”).57 He lists several heresies that he does not teach—belief in three separate gods, two distinct persons of Christ, Arianism—and he even denies by name the teachings of Servetus, who had been executed in Geneva for heresy in 1553.

The central point for Sozzini is that he believed these controversies to be niceties of the Christian faith—important to theologians but not necessary for salvation. The theme throughout the confession is that Sozzini worries about the liberty to raise questions on doctrine. He also worries that punishment for not embracing doctrinal language found neither in the Bible nor in the Apostles’ Creed is a step too far. One might say that Sozzini was radical about what constituted enough assent to doctrine for salvation. He saw the doctrine of the Trinity, Christology, and all other subjects derived from the ancient creeds as nonessential, so long as one held faith in Christ’s work on the cross. He treats the Apostles’ Creed as the earliest and only necessary creed:

I will never suffer myself to be deprived of this holy freedom of inquiring from my elders and disputing modestly and submissively in order to enhance my knowledge of divine matters; for there are not a few passages in the Scripture, the interpretation and exposition of which, by the doctors even who are entitled to eternal honor, are by no means satisfactory.58

Sozzini eventually made his way to Poland, where religious liberty was protected. Although he had not, by 1555, broken with the Swiss Reformed movement, Sozzini and his nephew Faustus Sozzini (1539–1604) eventually did so. The two not only later rejected trinitarian and christological teachings from the creeds but also helped establish the community known as the Polish Brethren, who later gave rise to the Unitarian movement. The groups in the eastern part of Europe were committed to the imminent return of Christ. This apocalyptic stance increased their desire to foster moral purity, a commitment to the Bible alone (with no creeds), and the practice of immersion as a sign of public commitment to the community.

In 1574, the Polish Brethren drafted their Catechesis and Confession of Faith. The text was far more radical than the 1555 statement by Laelius Sozzini, although he and Faustus had influenced the author of the confession, Georg Schomann, who served in the Minor Church in Kraków. The community had split over not only the more radical antitrinitarianism of the Sozzini family but also the teachings of Jan Łaski (1499–1560).

The confession and catechism were hard for those outside the Polish Brethren circles to interpret. The text rarely speaks overtly in the language of a confession, and instead answers almost all questions with a series of biblical citations. Indeed, the most common question asked of the reader is either “Where is it said?” or “Where is instruction?” followed by a set of verses quoted at length. It is crucial to note, however, that important passages of the Bible either are not mentioned or are reinterpreted to fit within an antitrinitarian formula. John 1 is a sufficient example for us to see this point. Typically, this passage was and is read as evidence for trinitarian orthodoxy (“The Word was with God, and the Word was God”). However, in the Polish confession, the verse is reworked to mean that the Son is merely used by God as an instrument of salvation. There is, therefore, “the one God the Father” only “who is most high.”59 The Polish Brethren base their radical commitment to the Father alone on the Shema from Deuteronomy 6:4, “Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God is one.” This passage opens the entire confession, and it is evident throughout each article that only the Father is to be considered truly God.

For example, when asked about Jesus as the Son of God, the next question states boldly, “He is a man, our mediator with God.”60 The text continues at length with scriptural proofs that Christ was a prophet, priest, and king, but it claims that nothing in the Bible points to his sharing divinity with the Father. Christ, then, could equally be described as Lord, though he was only a mediator, part of the created order. One question, for example, asks only, “Where is God said to have created this Jesus Lord and Christ?” The Brethren affirm their view with a long series of verses about Jesus being enthroned by God or glorified by God. The confession ultimately suggests that Christ is to be approached through “adoration and invocation,” which harkens to the language the Catholic Church used to describe pious interaction with Mary and the saints.61 Jesus, then, is our Master, but he is not God come in human flesh. The Holy Spirit is also explicitly denied worship or glory, and instead is described as “energy” or “power” of God.62 Shifting focus, the remainder of the confession and catechism focuses on the moral life, discipline from the community for sin, and how to pray to God the Father (but never to Jesus), since the logic of the confession stresses that Christians must focus on “imitating his steps . . . that we may find rest for our souls.”63

A notable contrast to the Polish confession was the Transylvanian Confession of Faith from 1579. The churches in Transylvania (present-day central Romania) were divided over matters similar to those in dispute in Poland, and even the king, John Sigismund, embraced a Unitarian position. The area was quick to embrace the Reformation, with cities divided equally in their adoption of Lutheranism or the Reformed position. Perhaps as a result, these cities maintained a position on religious freedom equal to that in Poland, although the role of the monarch in supporting Unitarianism had a strong appeal, especially among the upper classes. This confession, then, addresses the issue of Christ’s divinity in a brief statement (only a page or two in a modern printing). The first article states that “the genuine sense of Holy Scripture” requires believers to refer to the Son as truly God. Echoing language of the early creeds, they admit that Jesus “is to be worshipped and adored.”64 The confession mentions nothing about the Holy Spirit, though this may derive from the fact that Christology was its sole focus. In other ways, though, the confession walks the same radical path as other Anabaptist statements: Scripture alone, not creeds or historical orthodoxy, is to govern all our speech. The authors, therefore, refuse to use any language of hypostasis or persona, or to speak positively of Nicaea, Constantinople, or any of the ancient councils. Instead, they base their christocentric belief (though not necessarily trinitarian belief) on their reading of the Bible alone.

Conclusions

In this chapter we have seen a few differences between second-generation Protestant confessions and the earlier confessions discussed in the previous chapter. The most notable change from the earlier to the later confessions was the increasing sense of identity within each tradition, as the various forms of Protestantism continued to chart their own path over time. There are few signs that Lutheran and Reformed churches were still seeking to unite confessionally by the second generation. Luther was in the twilight of his years, leaving his final statement before he passed in 1546. The Reformed churches no longer wanted Wittenberg’s approval, but they were rapidly gaining ground in other parts of Europe. And finally, the Anabaptists had found an oasis in the eastern regions of Europe, and they no longer wrote as churches under the lash but as free citizens of Christ who wanted to govern themselves.

In spite of this increasing confessional identity, these later confessions give few hints of what had shaped them internally, either through controversy or theological development. Each group had been shaped into a tradition, but none had yet been tempered by trials into the form that it later showed. As a result, much of what we might expect is absent in these second-generation confessions. The Reformed confessions say nothing about the covenant or the Sabbath, and only little about predestination. Lutheran confessions speak of grace and justification, but do not give voice to the controversies on the Third Use of the Law or the ubiquity of Christ. Anabaptist confessions sketch only a very simple summary of their unique community life. And in the Anglican communion there was only the scant Forty-Two Articles—and with the reign of Mary, these were cast out of England. Perhaps the best way to understand Protestant confessions during this phase is to say they were maturing but not yet matured.

In the next two chapters we will explore some of the reasons these four traditions began to reach maturity. In chapter 16 we will look at Catholic and Orthodox responses to the Reformation—responses that made the schism with Rome permanent and closed off even a relationship with the Orthodox Church. Chapter 17 will then look at the trials and successes in each Protestant tradition, as the various groups wrote more detailed and more substantive confessions that capped off the first era of Reformation confessions.

1. For Luther’s views on rebellion, see Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 2, The Age of Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

2. A good recent book on Charles V, especially on the issues of international politics, is William S. Maltby, The Reign of Charles V, European History in Perspective (London: Palgrave, 2004).

3. For more on this, see Ryan M. Reeves, English Evangelicals and Tudor Obedience, c. 1527–1570, Studies in the History of Christian Traditions 167 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), chap. 1. On Luther’s change of mind, see Skinner, Age of Reformation, 206–38.

4. Theodore G. Tappert, trans. and ed., The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1959), 289. Also in CCFCT 2:122.

5. This is echoed in William R. Russell, Luther’s Theological Testament: The Schmalkald Articles (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995).

6. Tappert, Book of Concord, 289. Also in CCFCT 2:123.

7. Tappert, Book of Concord, 292. Also in CCFCT 2:125.

8. Tappert, Book of Concord, 293. Also in CCFCT 2:127.

9. Tappert, Book of Concord, 292. Also in CCFCT 2:126.

10. Tappert, Book of Concord, 294. Also in CCFCT 2:127.

11. Tappert, Book of Concord, 302. Also in CCFCT 2:134.

12. On this war, see Philip Benedict, Christ’s Churches Purely Reformed: A Social History of Calvinism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002).

13. Bullinger has been neglected for too long by historians, though thankfully a lot of recent work has been published on him. See especially Bruce Gordon, The Swiss Reformation (Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 2002); Bruce Gordon and Emidio Campi, eds., Architect of Reformation: An Introduction to Heinrich Bullinger, 1504–1575, Texts and Studies in Reformation and Post-Reformation Thought (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004). For a basic but authoritative survey of his life, see David C. Steinmetz, Reformers in the Wings: From Geiler von Kayserberg to Theodore Beza (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 93–99.

14. On Bucer, see Martin Greschat, Martin Bucer: A Reformer and His Times (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2004); David Wright, Martin Bucer: Reforming Church and Community (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).