Chapter 7

Cultivate Your Body Language

As you know, verbal language is important. And so is nonverbal language. The big secret is that what really matters is the alignment and coordination of your verbal and nonverbal communication. This is what Shakespeare meant when he advised, “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.” When your words say one thing and your body says another, you will feel uncomfortable and anxious, and you will confuse your audience and weaken your credibility, leading to more discomfort and anxiety.

An ancient Chinese proverb states “Beware of the man whose stomach does not move when he laughs.” If your stomach doesn’t move when you laugh, then your laughter seems phony and forced. Your posture, gestures, and movements can enhance your presentation dramatically, or they can sabotage an otherwise thoughtful and well-organized talk. When your body and your message are in harmony, your audience perceives you as genuine, but if there is a disparity between your words and your posture, gesture, facial expression, or voice tone, they are likely to be suspicious and less receptive.

Your body language will always be more integrated when you have clear objectives for your presentation and a strategy for making it memorable. When people aren’t clear about their objectives and haven’t organized their message, they say “um” and “ah” more frequently, and they’re more likely to have a guarded posture and to make unnecessary gestures and awkward movements. Being well prepared and focused on communicating a message you believe in will do more for your body language than anything else. Preparation and clarity of intention and message are necessary but not always sufficient for great presentations.

Why? Because most people have habits and unconscious patterns of tension that become exaggerated in front of a group, to the detriment of their effectiveness. Professional presenters work on freeing themselves from these constraining habits as they cultivate ever more articulate and powerful body language. I’ve been studying and teaching methods to cultivate this freedom during my entire career, and in this chapter, I will share with you the most powerful means I’ve discovered for finding freedom and flow in your presentations and in your life.

Presence: A One-Minute Pose or a Way of Being?

In a study entitled “Power Posing: Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance,” Amy Cuddy and her colleagues reported on their exploration of this question: “Humans and other animals express power through open, expansive postures, and they express powerlessness through closed, constrictive postures. But can these postures actually cause power?”

Their answer, popularized in Cuddy’s TED Talk, is yes.

The researchers concluded, “By simply changing physical posture, an individual prepares his or her mental and physiological systems to endure difficult and stressful situations, and perhaps to actually improve confidence and performance in situations such as interviewing for jobs, speaking in public, disagreeing with a boss.” The study also suggests that adopting more powerful body positions may “improve a person’s general health and well-being.”

Cuddy and her colleagues observed that brief power poses such as imitating the jaunty hands-on-hips stances of Superman or Wonder Woman not only help individuals who adopt them feel more confident, but they also affect the way others perceive those individuals.

In contemporary science this finding has been received as something of a revelation, whereas thespians and martial artists have been studying these effects in a detailed and practical manner for millennia.

You can change your physiology by power posing before presenting, but you’ll probably discover that unless you have a practice to make your everyday movements and posture more powerful, the effects of the short-term pose will not be sustainable. And you may look like an idiot.

Body-Message Synchrony: Aligning Your Body Language with Your Words

In Japan people greet one another with a bow. The traditional salutation in India is the namaste, a slight bow with hands in the prayer position. Hugs and embraces are common in many parts of the world. In many places, the handshake reigns. What do all these gestures have in common? They all convey the reassuring message “I am friend, not foe.” Our body language communicates reassurance, authority, confidence, and trustworthiness, or the lack thereof.

People who appear shifty or crooked are viewed with suspicion; those who are straightforward and upright are perceived as honest and strong.

In a study entitled “Attracting Assault: Victims’ Nonverbal Cues,” Betty Grayson and Morris Stein showed videotapes of people walking down a street in New York City to a group of convicted muggers and asked them to rate each person’s “muggability.” As you might expect, individuals who displayed an obvious infirmity in their movement were rated most muggable. The muggers also targeted people who moved in a stiff, slumped, awkward, distracted, or aggressive fashion. The least muggable were those with an upright carriage and a relaxed but purposeful gait.

Whenever you enter a meeting room or walk onstage to present, the audience instinctively and immediately assesses your muggability. How can you become less muggable and cultivate a more powerful presence?

Some presentation training courses aim to teach you how to fake authority through power poses, gestures, and dominance cues. It’s better to allow your true authority to emerge by cultivating body language that is natural, expressive, and authentic.

You can do this by developing body-message synchrony, ensuring that your posture, movements, gestures, facial expressions, eye contact, voice tone, volume, and inflection are in sync with your message. Start, like professionals do, with authentic passion to communicate something of value to your audience and by clearly defining your objectives and organizing a memorable message. But there’s another secret as well: professionals work at unlearning the unnecessary habits that constrain self-expression.

Although the elements of body language function interdependently, let’s simplify our approach to unlearning by examining each individually.

Stance

Boxers and martial artists usually adopt some kind of triangular stance so that they offer a minimal target to their opponents. The basic message of a fighter’s stance is “You can’t hit me and I’m going to hit you.” Baseball batters and golfers organize their stance so they can address the ball. Their body language says, “I’m ready to knock this sphere out of the park or onto the green.”

As a communicator you usually don’t want to give the impression that you’re preparing to whack your audience; rather, you want to convey a sense of welcoming, openness, and trust. You do this by facing your audience directly with an upright, balanced, and open stance.

A reliable basic stance is the simplest and most powerful way to cultivate poise and presence, helping you connect with any kind of audience in any circumstance. It also becomes a point of departure for graceful, expressive, confident movement.

The most challenging aspect of an actor’s training is not memorizing complex soliloquies or learning strange accents; a would-be thespian’s greatest challenge is learning to stand and move in an expansive, natural, unaffected way. Standing in an upright, balanced, and natural way is the most important element in cultivating a commanding stage presence. Here’s a wonderful way to cultivate these qualities.

STAND EASE: Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!

Drawn from ancient Chinese lineages, the following practice is the single most effective method I have discovered for developing presence and cultivating life energy. If you practice this a few minutes a day and eventually work your way up to twenty minutes daily, you’ll find that you have more energy, confidence, and ease in all your interactions but especially while presenting. Ideally, you would do this in a quiet, beautiful place. I like to practice on a hilltop near my home with a view of the river but also find that it’s an ideal activity while waiting at the airport to board a plane, or anywhere else. (You can also apply most of the elements while you’re sitting, if you like.)

STAND EASE is an acronym to help you remember the elements that make this simple practice so powerful:

Smile. Begin with a subtle smile, like the Buddha or Mona Lisa. Let the smile shine in your eyes. This shifts your physiology immediately and helps you feel more equanimity. And you’ll discover that this genuine smile also helps others feel more relaxed and comfortable in your presence.

Tongue. Gently place the tip of your tongue on your upper palate, just behind your teeth. If you say the phrase Let go aloud, you’ll notice that as you make the L sound in Let, your tongue naturally moves to this point. This is an acupuncture point that connects the energy that flows up your back with the energy that flows down your front, thereby helping you feel more balanced and at ease.

Align. Align your body around the vertical axis. That’s another way of saying “stand at your full stature.” When we’re stressed, we tend to contract and diminish our stature, and that compromises our presence and energy. While you practice standing at your full stature, always avoid locking your knees. Keep the knees soft, and remember that they are meant to be weight-transferring joints, not weight-bearing joints.

Natural. If you look at young children or aboriginal people from any culture who haven’t been corrupted by so-called civilization, you’ll notice that they are upright and aligned around the vertical axis in a natural, easy way. Sitting in chairs all day makes it easy to forget that this natural poise is your birthright.

Distribute. With your feet about shoulder-width apart, sense the feeling of your feet on the floor. Distribute your weight evenly between your feet, and between the ball, heel, and inner and outer parts of each foot. Even weight distribution gives a message of evenness and balance to your whole nervous system and supports psychophysical equilibrium.

Exhale. Exhalation encourages relaxation and stress release. Exhale by compressing your belly, lower ribs, and lower back. When under stress, people tend to gasp for air and try too hard to breathe in, over-activating the upper chest and neck muscles. Instead, breathe out from your center, and then just allow the air in through your nose gently. Breathing easily, slowly, and smoothly from your center will help you feel more centered.

Aware. Awaken and expand your awareness. Attune to everything within and around you. When we are overstressed, we tend to narrow our focus. By expanding our attention we also expand our sense of ease and the power of our presence.

Soften. Soften your eyes and your belly. Feel the weight of your shoulders and your jaw, and you’ll notice that they soften, too. Maintain your alignment, and let everything be soft.

Expand. Allow your energy and presence to expand. (As you practice STAND EASE over time, you may begin to notice an effortless and enjoyable sense of buoyancy and energetic expansion.) When you’re preparing to present, intentionally fill the entire room with your energy and presence. Create a welcoming field of vivacity. Don’t be surprised when people come up to you after you present and say something like, “Wow! I feel so energized by your presentation!”

In addition to daily formal practice of this standing meditation, you can also practice the stance in everyday life. Instead of fidgeting or checking a device when you’re waiting in line, you can practice STAND EASE. As you practice over the weeks and months, you’ll begin to discover that you feel more at home and comfortable in your body and that you can transfer that poise to social situations and ultimately to developing a powerful presence onstage.

In other words, Don’t just do something, stand there! As the Tao Te Ching advises, “In stillness the muddied water returns to clarity.” If you want to be clear and present, then practice this simple standing meditation.

Movement

The stillness you cultivate through standing meditation sets the stage for developing more grace and power in all your movements, both in everyday life and on the stage. The human brain is designed to follow movement. And when you’re presenting, you’re communicating with your audience through every movement, consciously or not. When your movements are in sync with the flow of communication, they add depth and resonance to your message. When they’re out of sync, they may sabotage your communication. For example, rocking and swaying movements might be fine if you are speaking about drunkenness or the perils of ocean travel and using these movements for illustrative purposes. But if you are just shifting around unconsciously, you may distract or even nauseate your audience.

You can discover and begin to unlearn your unnecessary, unconscious movements by watching yourself on video, ideally with the help of a supportive and perspicacious friend or colleague who will give you accurate feedback. While learning to let go of distracting movements, avoid the trap of standing frozen in place. If you are not confident in your movement, invest more time exploring the basic stance.

When you free yourself from unconscious, habitual distracting movements, you’ll discover that natural, expressive movements emerge effortlessly, like, for example, walking toward the audience to emphasize a particularly important point or moving from one side of the room, stage, or riser to the other to emphasize your connection with the whole audience.

Gestures

Many years ago, some friends and I spent a summer traveling through Italy. We arrived in Rome with a list of three recommended pensioni, inexpensive bed-and-breakfasts. The first place on our list, Pensione Rosa, had no vacancies. The second, Pensione Alberto, was also full. We asked the owner if he could tell us if we were likely to find room at Pensione Anna, the last place on our list.

Alberto responded by repeating the name Pensione Anna as he drew his sleeve, all the way from his shoulder to his fingertips, across his nose. He completed this gesture of unqualified disgust by casting a large quantity of imaginary nasal discharge violently to the floor. His gesture was so powerful that decades later if a friend mentions traveling to Rome, I’m quick to warn, “Don’t stay at Pensione Anna!”

Gestures have tremendous impact on your effectiveness as a communicator. There are two keys to making that impact positive. The first is to avoid unnecessary gestures. Change rattling, pen fondling, excessive face scratching, nose wiping, hair adjusting, and genital guarding are among the most common nervous gestures that create unintended results. Observe yourself in a mirror or on video, and pare superfluous gestures from your presentation. If you aren’t sure what to do with your hands, just allow them to rest at your sides.

The second key is to discover your natural gestural language and exaggerate it. Although you do not have to go as far as Alberto, you can increase your impact by telling your story with your hands. Let your natural gestural language emerge and expand. Just as you need to increase the projection of your voice to reach a large group, you must project your gestures.

Shyness leads many people to suppress their natural gestural expression. With appropriate feedback, however, you can overcome this self-limitation.

An executive of a Swedish shipping company provides a delightful example. In a presentation meant to describe his company’s most impressive vessel, he held his hands in front of his solar plexus no more than a few inches apart. As he watched himself on video, he realized that this was not an accurate gestural representation of his company’s flagship. His smile suggested that he understood the need to move beyond his self-imposed constraint.

In the next take, he doubled the size of his gesture. But the video clearly demonstrated that his gestural frame was still too small for the picture he intended to convey. Mustering his courage for a final take, he flung his arms to full horizontal extension while booming out the words, “We have really big tanker.” Later, when he watched the tape, he was amazed to discover that the gesture, which had felt grossly exaggerated to him, actually looked natural and appropriately expressive.

You can awaken your natural expression by watching yourself on video. Study how your exaggerated gestures complement your message. Other useful exercises include miming your presentation, experimenting with gestures in everyday conversation, and playing charades.

Shakespeare provided the essential wisdom on gesture and body-message synchrony in Hamlet, when he reminded us: “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.” For most people this means being more expressive by making bigger more dramatic gestures. Shakespeare counseled, “Be not too tame.”

Of course, some folks get carried away and overdo it, and that can distract from the power of your presence. Shakespeare warned, “Do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus.” He guides us to discover poise — the right amount of energy in the right place at the right time — by expressing ourselves powerfully and gracefully, advising, “for in the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness.” And, ultimately you discover this for yourself through your own exploration and self-reflection. In Shakespeare’s words, “let your own discretion be your tutor.”

Eye Contact

Boxers, mixed martial artists, and other fighters aim to gain an advantage before the contest begins by establishing dominant eye contact. The eyeballing between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in the Thrilla in Manila match, and the gaze between Wanderlei Silva and Mirko Cro Cop in their first UFC battle, are among the most chilling examples. As one comment on the latter encounter expressed it, “Silva looks like he’s about to kill someone. Cro Cop looks like he already has.” (You can see original footage if you do an internet search for “best staredowns in fighting history.”)

On a much gentler and more romantic note, at the end of the Academy Award–winning film Casablanca, Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart communicate volumes of heart-wrenching emotion through what is perhaps the greatest eye-contact scene in movie history, rivaled only by the phenomenal ocularly mediated magic between Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Their portrayal of love at first sight, as their eyes meet across a fish tank, offers a defining image for that classic phrase.

Our eyes, as Shakespeare observed, are “the windows of the soul.” They express the full range of human experience, from threat and terror to intimacy and passion. Of course, in most presentations you are not trying to stare down or romance your audience. Your aim is to make contact so you can keep their interest and communicate your message. Eye contact enables you to read your audience and monitor your effectiveness. Is your audience bored? Are they confused? Enraptured? Tired? The answer is right in front of your eyes.

When you’re making a point in a conversation with a friend, you naturally watch your friend’s eyes to monitor the state of connection and to see if she’s understood what you’re saying. If her expression appears quizzical, you may ask if she has a question about what you’re saying. If your eyes wander off while your friend is speaking to you, she might ask you to return your focus to her.

Eye contact is normal and natural in everyday conversation, and professionals know that it is as well when speaking to a group. Making eye contact with members of your audience promotes a sense of connectedness and rapport that makes them much more available to your influence.

When you engage people’s eyes, you establish trust, draw interest, and access channels of influence. Although relatively easy in one-to-one communication, many speakers find it difficult to make eye contact with people in groups. This difficulty usually stems from viewing the audience as an impersonal mass. However large your audience, you can still speak to them as individuals.

If you are uncomfortable making eye contact with an audience, try this exercise. While you’re standing onstage or at the front of a meeting room, pick out the friendliest-looking people sitting to your right, your left, and straight in front. Use them as anchors for eye contact. Engage their eyes for two or three seconds at a time. By focusing on representatives from each part of the room, you give the whole audience a greater sense of your involvement and interest in them. As you become comfortable with your friendly anchors, expand your gaze to meet other members of the audience.

When you master this, try a more challenging exercise. Seek out the unfriendliest-looking people from each part of the room, and draw them out by engaging their eyes in a confident and friendly manner.

I once attempted this while giving an after-dinner speech to a group of investment bankers. The group was just finishing an elaborate meal that had begun with cocktails and proceeded through several wine-accompanied courses. As they sniffed their cognac and settled back in their chairs, I rose to deliver my remarks.

Among the many tired and distracted candidates for anchors, I chose three granite-faced bankers who seemed committed to acting as though there was no speaker. Launching into the presentation, I sought them out with my eyes, looking beyond their apparent disinterest. Halfway through the speech, two of the three shifted their positions. Their postures opened and their eyes said they were with me. The third fellow remained slumped over, arms tightly folded, expressionless.

As I began my closing, I could see from the nods and thoughtful looks that the audience, with the exception of my third anchor, was getting the message. I made one last attempt to draw him out with my eyes, to no avail. Finally, I spoke my last sentence — just as he passed out and collapsed on the floor!

I can’t guarantee 100 percent success — or that you’ll win over two out of three hostile listeners and knock the third one out cold. But you will find that natural, lively eye contact is fundamental to mastering the art of public speaking.

And you’ll prepare yourself for success in front of a group if you practice seeing with alert, receptive “listening” eyes in your everyday conversations.

Voice

When I was in junior high I’d stay awake for hours after bedtime contemplating the meaning of life and the vast emptiness of the cosmos. Why were we created? What if we didn’t exist? What happens when we die? These questions made me anxious, and to help me fall asleep I relied on a golden globe-shaped radio that I kept tuned to a station that featured what former FBI hostage negotiator and founder of the Black Swan Group Chris Voss calls “a late-night FM DJ voice.” When I remember the sound of that voice from decades ago I feel more relaxed in the present. Voss trains his students to use that voice to help put others at ease in stressful negotiations, and he emphasizes the importance of shifting one’s tone of voice as a means of directly influencing the brain, mood, and attitude of one’s counterparts.

Your voice has a profound effect on your communication, whether in a negotiation or a presentation. Try a little experiment. Pick any sentence or phrase and alter its meaning by changing your tone, inflection, and volume. For example, try to make the words “Yes, I am sure you are right” mean “No, I am sure you are wrong.”

In addition to inverting the meaning of words, your voice can express an amazing range of complexities and nuances of meaning. Consider, for example, how much you may know from the tone of voice with which a friend or relative answers the telephone. Can you sometimes tell that someone is depressed or annoyed or excited and enthusiastic just from the way they say “hello”?

The tone, inflection, pacing, and volume of your voice have a powerful effect on others in all aspects of life and especially in public speaking. And in virtual presentations, your voice becomes even more important.

Let’s consider how you can use your voice to accomplish your objectives.

Expressive Variation

Do you know why you are able to fall asleep despite the rumblings of your air conditioner or the sounds of traffic passing outside the window? Your brain contains a marvelous system called the reticular activating mechanism. It tunes out repetitive noise. The same mechanism wakes you in response to a sound that stands out from a monotonous background, such as your alarm ringing.

Unfortunately for boring speakers, the reticular activating mechanism also helps an audience sleep through presentations delivered in a monotone voice. By varying your tone, inflection, and volume in coordination with your content, you send a stream of wake-up calls to your audience’s brains, dramatically increasing the impact and memorability of your presentation. So, for example, when you lower your volume and slow your pace, you can create anticipation for what you’re about to say. When you ask a question, what would it sound like if you used a questioning tone of voice? When you want to express passion, you might raise your volume. But if you do any of these exclusively, audiences will tune you out just like a rumbling air conditioner. So mix it up!

The Power of the Pause

Um, ah, the pause is, you know, uh, like, a really important part of, ah, using the, ah, voice. The average speaker is afraid to pause. As a result, most people either talk too fast or use filler noises such as um, ah, you know, and like.

In the Tao Te Ching, Chinese sage Lao Tzu reflected,

We join spokes together in a wheel,

but it is the center hole

that makes the wagon move.

We shape clay into a pot,

but it is the emptiness inside

that holds whatever we want.

We hammer wood for a house,

but it is the inner space

that makes it livable.

We work with being,

but non-being is what we use.

The pause is the hub, the hollow, that brings your words to life. Pausing gives you time to breathe, to center yourself, to think. It gives your audience the opportunity to absorb and reflect on your message. Pausing conveys confidence as it captivates your audience’s attention.

Develop your “pauseability” by recording and listening to yourself. Experiment with extending your pauses. Explore appropriate timing. Notice the frequency of filler words, and strive to eliminate them. Instead of um-ing and ah-ing, pause. Pausing at the right time has a hypnotic effect on an audience. It draws them to you. And it allows you to breathe fully and think about what you’re saying.

As Mark Twain observed, “The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective as a rightly timed pause.” Twain pays tribute to the power of the pause in poetic terms: “That impressive silence, that eloquent silence, that geometrically progressive silence which often achieves a desired effect where no combination of words howsoever felicitous could accomplish it.”

And he explains how he developed his attunement to the timing of the pause: “For one audience, the pause will be short; for another a little longer; for another a shade longer still; the performer must vary the length of the pause to suit the shades of difference between audiences....I used to play with the pause as other children play with a toy.”

I was thrilled when I discovered these reflections from Twain because they mirror my own learning and method; playing with the pause like a toy and reading the audience’s response in the moment is a delicious expression of mastery to which we can all aspire. Learning to pause appropriately onstage, online, or in front of a conference room is a simple, powerful way to establish authority and demonstrate confidence. If you want to do this with confidence when presenting, you must practice in your everyday conversations.

Integrating Stance, Movement, Gesture, Eyes, and Voice with the Alexander Technique

Your voice rides on your breath. Free breathing liberates your voice, and a balanced, expansive upright posture frees your breathing. As you develop your basic stance and ease of movement, your breathing and voice will improve. And, as noted above, pausing gives you time to breathe and make eye contact with your audience. Moreover, your brain is about 3 percent of your body’s weight, but it uses about 30 percent of your oxygen intake, so fuller, easier breathing means a more oxygenated brain, which leads to greater clarity and presence while speaking.

Despite a sometimes grueling speaking schedule, I have never lost my voice. I apply a method that gives me access to the natural, expressive, and authentic use of my voice and body language. This same method is also an effective means for developing self-knowledge, changing habits, and transforming fear. It is called the Alexander Technique, named after its founder, F.M. Alexander. Alexander Technique teachers use their hands in an exquisitely subtle manner to give their students an experience of ease of movement and freedom from the unconscious and unnecessary tension that interferes with breathing, vocal usage, and stage presence. Frank Jones, former director of the Tufts University Institute for Psychological Research, describes the technique as “a means for changing stereotyped response patterns by the inhibition of certain postural sets” and as “a method for expanding consciousness to take in inhibition as well as excitation (i.e., ‘not doing’ as well as ‘doing’) and thus obtaining a better integration of the reflex and voluntary elements in a response pattern.”

My favorite description of the technique was offered by Gertrude Stein’s brother Leo, who called it “the method for keeping your eye on the ball applied to life.”

The technique is taught at the world’s premiere theater and music schools, such as the Juilliard School and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. It’s a trade secret of many of the world’s great performing artists, including Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Sting, John Cleese, Mary Steenburgen, Sir Georg Solti, Sir Paul McCartney, Deborah Domanski, John Houseman, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Hal Holbrook, Sigourney Weaver, David Hyde Pierce, Bernadette Peters, and Sir Ian McKellen.

When I began my speaking career, I was usually the youngest person in the room. The Alexander Technique gave me a sense of poise and presence that allowed me to hold my ground in interactions with people senior to me. Now I’m often the oldest person in the room, but I usually have the most energy and the best posture, thanks to this technique.

In addition to daily practice of STAND EASE you can also cultivate a stronger, clearer presence by studying the Alexander Technique. Ideally, you would take private lessons with a qualified teacher and/or attend a workshop, but in the meantime, here is a simple practice that can help you get started.

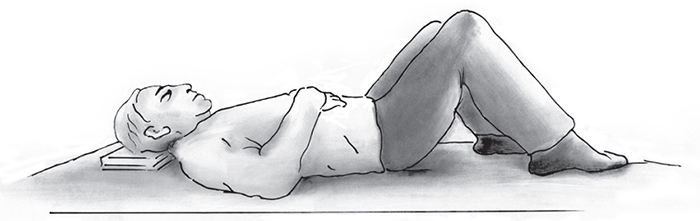

The Balanced Resting State

All you need to benefit from this procedure is a relatively quiet place, some carpeted floor space, a few paperback books, and fifteen to twenty minutes.

Begin by placing the books on the floor. Stand approximately your body’s length away from the books, with your feet shoulder-width apart. Let your hands rest gently at your sides. Facing away from the books, look straight ahead with a soft, alert focus. Pause for a few moments. Review the elements of STAND EASE.

Breathing freely, become aware of your feet on the floor, and notice the distance from your feet to the top of your head. Keep your eyes open and alive, and listen to the sounds around you for a few moments.

Then, moving lightly and easily, ease yourself down to the floor. Supporting yourself with your hands behind you, place your feet on the floor in front of you, with knees bent. Continue breathing easily.

Let your head drop forward a bit to ensure that you are not tightening your neck muscles and pulling your head back. Then, gently roll your spine along the floor so that your head rests on the books. The books should be positioned so that they support your head at the place where your neck ends and your head begins. If your head is not well positioned, reach back with one hand and support your head while using the other hand to place the books in the proper position. Add or take away books until you find a height that encourages a gentle lengthening of your neck muscles. Your feet remain flat on the floor, with your knees pointing up to the ceiling and your hands resting on the floor or loosely folded on your chest. Allow the weight of your body to be fully supported by the floor.

Rest in this position. As you rest, gravity will lengthen your spine and realign your torso. Keep your eyes open to avoid dozing off. Bring your attention to the flow of your breathing and to the gentle pulsation of your whole body. Be aware of the ground supporting your back, allowing your shoulders to rest as your back widens. Let your neck be free as your whole body lengthens and expands.

After you have rested for fifteen to twenty minutes, get up slowly, being careful to avoid stiffening or shortening your body as you return to a standing position. To achieve a smooth transition, decide when you are going to move, and then gently roll over onto your front, maintaining your new sense of integration and expansion. Ease your way into a crawling position, and then up onto one knee. With your head leading the movement upward, stand up.

Pause for a few moments. Listen. Again, feel your feet on the floor and notice the distance between your feet and the top of your head. You may be surprised to discover that the distance has expanded. Review STAND EASE. As you move into the activities of your day, avoid compromising this expansion, ease, and overall uplift. In other words, be mindful, and free yourself from the habits of hunching over your steering wheel while driving, clasping your toothbrush with a death grip, craning your neck and narrowing your shoulders to manipulate your cell phone, or raising your shoulders to slice a carrot in the kitchen. As you cultivate more mindful and graceful movement in daily life, you’ll discover that doing so supports a much greater sense of ease and poise when you’re in front of a group to present.

For best results, make the Balanced Resting State a daily practice. You can do it when you wake up in the morning, when you come home from work, or before retiring at night. If you don’t have fifteen to twenty minutes, you can still benefit by investing five to ten minutes. The procedure is especially valuable when you are preparing to give a presentation, since it effortlessly helps you manifest an upright, easy poise.

The Balanced Resting State

In her critically acclaimed 2008 debut with the Santa Fe Opera, in the role of Princess Zenobia in Handel’s Radamisto, lyric mezzo-soprano Deborah Domanski began one of her arias while rolling along the stage floor after being launched from an unfurling carpet. When asked how she was able to project her voice so that it could be enjoyed in the back rows of the packed 2,200-seat outdoor theater, Domanski explained, “My daily practice of the Balanced Resting State and lessons with my Alexander Technique teachers make all the difference.” Twelve years later Domanski sings with even richer tone and more multidimensional coloratura, all with less effort and greater stage presence. Her secret? “My voice teacher, the legendary actress and vocalist Beret Arcaya, is also an amazing Alexander Technique teacher. She’s thirty years older than me, and she sings beautifully. She’s taught me how to access ever greater freedom of movement and breath and the result is that singing gets easier and my voice is more reliable.” Domanski, who also teaches voice and stage presence to professional singers and public speakers, adds, “When people stop trying too hard and learn to allow the voice to float on the breath like a surfer rides a wave or an eagle rides a thermal, they’re often amazed at the quality of the sound that emerges.”

DOSE: The Easy-to-Prepare Elixir to Transform Fear

Balanced Resting State and the STAND EASE meditation, practiced daily, are two of the simplest and most effective means for strengthening your presence through upright, aligned body language. And if you study the Alexander Technique, you’ll be tuning your public speaking instrument like Yo-Yo Ma tunes his cello.

Nevertheless, despite everything you’ve practiced, acute fear can still arise as you anticipate giving a presentation, and I want you to be prepared with a few more simple, practical methods for overcoming it. Fear releases powerful hormones into your bloodstream, with corresponding muscular contractions. This reaction, called the fight-or-flight response, is instinctive. Nature designed it to mobilize us to escape from, or fight with, would-be predators.

Before or during speaking engagements, however, it’s not good form to dash out of the room or to physically assault the audience. So most speakers just sit there, tightening up and stewing in their own stress juices as they wait their turn. I call this sitting in the CAN, an acronym that stands for cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine. These are the stress biochemicals that are streaming through your system when you experience stage fright.

DOSE is an acronym for the biochemicals that you can access to get those butterflies into formation: dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins, which are sometimes known as the “happiness chemicals” or the “angel’s cocktail.”

How can you get out of the CAN? Give yourself a DOSE! Here are a few ways to do that.

Work Out

The simplest and most effective thing you can do to adjust your physiology is to work out before you present. If possible, arrange to do vigorous exercise earlier in the day when you are scheduled to speak. You’ll get the most benefit from an intense activity that makes you pour sweat. Hitting a heavy bag or whacking a racquetball or pickleball are ideal movements. By acting out the activities of running and hitting, you release the dammed-up energies of fight-or-flight and shift into flow.

If you can’t make it to the gym, then instead of basting in anxiety, find a private space and do some of the following pre-presentation warm-ups. You will metabolically transform your stress juices into happiness chemicals and begin to release the corresponding patterns of muscular contraction.

Shadowbox

If you can’t run, hit a heavy bag, or pound a ball against the wall, try shadowboxing. Dance around and throw some punches for three minutes. You’ll be surprised at how much better you feel.

Make Funny Faces and Laugh Loudly

Fear can lead you to take your presentation, and yourself, far too seriously, leading you to freeze your face into a rigid, zombie-like mask. Do what professional actors do, and save face by making funny faces. Stand in front of a mirror and make the most fearful look you can muster. Experiment with a full range of extreme expressions. Try anger, surprise, sadness, and joy. Finish by making the stupidest faces imaginable. Let your jaw slacken as your tongue hangs out. Then deliver the first few minutes of your presentation in this slack-jawed silly manner. Besides encouraging a more lighthearted attitude, these exercises mobilize your face and make you look and feel more relaxed and expressive. If you practice looking like an idiot before you present, you’re less likely to look like one while you speak.

Making funny faces is also a reliable way to make yourself laugh, and laughter is one of the best ways to stimulate endorphin production and transmute stress.

Listen to Your Favorite Uplifting Music

On his way to the arena, and in the locker room before the game, LeBron James, and many of his colleagues, enjoy their favorite tunes on headphones. High-performing athletes in every sport know that the right music helps gear them up to perform at their best. The same thing is true for public speaking. A study recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explains what James and his colleagues know through experience: listening to the music you love will make your brain release more dopamine.

Enjoy Some Aromatherapy and Chocolateopathy

The scents of lavender and vanilla stimulate the production of endorphins, and so does dark chocolate. Dark chocolate is a great “pregame snack” for presenters, and a whiff of lavender or vanilla is a proven mood booster. You can even find dark chocolate infused with lavender and vanilla. Have a little before you speak, and then plan to have more when you’re done as a celebration. Anticipating celebration raises dopamine levels significantly.

Connect with the Audience Informally

As we learned in an earlier chapter, arriving early for your presentation allows you to meet members of your audience. Besides the benefit you get from discovering what may be on their minds, you’ll also find that if you can connect with a few people, making genuine eye contact, exchanging smiles, handshakes, and ideally hugs, you feel so much more relaxed and connected with the audience before you begin. The interpersonal connection releases oxytocin and helps you and the audience feel more at ease.

As you get out of the CAN and give yourself a DOSE in the manner prescribed above, you’ll find yourself using much more natural, poised, and expressive body language.

Eva Selhub, former clinical director of the Benson-Henry Center for Mind Body Medicine and a leading expert on stress and resilience, comments, “These simple practices can help you gain control of your own biochemistry so you can access a sense of well-being, and a more open state of mind, that will translate into more ease and clarity during a public presentation. The stress hormones and stress systems that are normally overactivated when an individual feels threatened or disconnected are kept in check, therefore inhibiting the detrimental and harmful effects of stress and the associated by-products, thus allowing for more social connection and attraction.”

She adds, “My endorsement of these practices is more than just my opinion as a scientific researcher; it’s also based on my experience as a professional public speaker myself.”

Here is one more practice to help you be at your best when you speak publicly.

Getting the Stress Out of Your Bones

In a recent study published in the journal Cell Metabolism, Gerard Karsenty and his colleagues share their research into the role of our bones in the stress response. Karsenty explains that our bones release the hormone osteocalcin in response to acute stress. The study included measuring osteocalcin levels in subjects who were experiencing stage fright.

Standing meditation aligns and strengthens the bones, and that may be part of why it’s so effective in generating an abiding sense of calm. A complementary practice evolved over thousands of years is particularly useful in preventing or reversing the fightor-flight response. It’s called Bone Marrow Cleansing. Here’s the simplest version that can help you get the stress out of your bones just before you go onstage.

Adopt your best standing posture, and apply STAND EASE for thirty seconds. Begin by gently shaking your whole body, bouncing up and down while keeping your feet on the floor. Kindergarten teachers call this “getting your wiggles out,” and it happens to be an ancient energy-harmonizing practice that is also ideal for grown-ups. You get the most benefit, however, if you do it as a child would, with abandon. What are you abandoning? Overseriousness, anxiety, and osteocalcin! Bounce and shake for about a minute, and in the last twenty seconds go all out and add some sighing and blithering sounds for maximum benefit. Then come to complete stillness. Do STAND EASE for thirty seconds. You’ll feel your hands and much of the rest of your body tingling in a pleasurable way.

Next, as you inhale through your nose, reach out and up toward the sky with palms up. Look up to the sky, and form the intention of gathering the creative, healing energy of the universe. As you draw the breath in, your lower belly expands. Then as you begin to exhale through either nose or mouth, you look within as your palms turn to face the Earth, with the intention of washing your whole being, right through to your bone marrow, with the creative, healing energy you just gathered. Wash through your whole body, and release any remaining stress, tension, and osteocalcin into the Earth. Repeat for seven cycles.

All these practices will help you get out of the CAN and give you a DOSE. To get the most benefit, and to prepare yourself for long-term success in mastering the art of public speaking, maintain a daily practice that promotes the integration of body, mind, and heart. In this chapter I’ve shared with you much of what I’ve learned and what I myself practice. In addition to working out, listening to beautiful music, and enjoying dark chocolate, I do the STAND EASE meditation and apply the Alexander Technique and the Balanced Resting State every day so that when I present it’s easy to feel poised and present.