SIMILARITIES BETWEEN LINCOLN AND DAVIS

Legend clouds reality. Displayed as polar opposites in popular history, American presidents Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis in fact shared several traits and experiences. Throughout their lives both men displayed exceptional intellect, uncommon kindness, resilience despite hardships, and an unbreakable commitment to principle. Arguably, the outcome of the Civil War helped make these and other attributes appear as strengths in one man and weaknesses in the other.

Unquestionably there were differences. Lincoln’s formal schooling totaled less than one year. By comparison, Davis attended prominent schools, including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Lincoln, a skeptic especially in his youth, never joined a church, although he would occasionally attend Presbyterian services with his wife. Davis, a long-standing member of his church, was far more religious. In opposition to the patient and earthy Lincoln, Davis possessed a lightning-quick temper and a preoccupation with honor. To achieve desired ends, Lincoln relied on timing and consensus, whereas Davis, the officer and slaveholder, was accustomed to being obeyed.1

Along with contrasts, there remain a number of fundamental similarities shaping and defining the two individuals who would lead their governments through a war neither wanted. The following are ten predominant similarities between Lincoln and Davis, shown in chronological order.

1. Both were Born in Kentucky

One hundred miles and less than a year separated the births of the two presidents. Just as legend states, Lincoln was born in a log cabin, but so was Davis.

In Kentucky’s southwestern reaches, near present-day Fairview, Samuel and Jane Davis welcomed their new son on June 3, 1808. They named him Jefferson in tribute to their current president of the United States. They also gave him the middle name of Finis—Latin for final, perhaps hoping this tenth child would be their last. He was.

Two seasons later, on February 12, 1809, Abraham Lincoln entered the world just south of Hodgenville, Kentucky. Second child of Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, he was named after his paternal grandfather.

Both families moved out of state a few years after their sons were born, the Lincolns first to Indiana and then Illinois, the Davises to Louisiana then Mississippi.2

Lincoln and Davis remain the only presidents born in Kentucky.

2. Both Served during the Black Hawk War (1832)

Lieutenant Davis of the U.S. Army was posted in and around northwestern Illinois when Chief Black Hawk led hundreds of Sac and Fox eastward to reclaim the area as their own. Missing out on actual combat, Davis later escorted the captured chief down the Mississippi to federal authorities in Missouri. Davis reportedly displayed much kindness to his prisoner.3

Perhaps in memory of his grandfather who was killed by a Native American, but definitely to escape his shopkeeping job in New Salem, Lincoln volunteered for the Illinois militia when the Black Hawk War broke out. He joined a company that consisted mostly of friends and neighbors. They elected him captain, a tribute he recalled later as one of his life’s greatest moments.

Lincoln’s days as an officer passed without incident, although he and his company were twice reprimanded for disobedience. After his thirty-day enlistment expired, he mustered for two more sessions as a private, but he saw no action save for “many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes.”4

Among others who served in the Black Hawk War were Winfield Scott (later ranking Union general), Robert Anderson (Union commander at Fort Sumter), Joseph E. Johnston (Confederate general), and Albert Sidney Johnston (Confederate general killed at SHILOH).

Jefferson Davis was thirty-nine years old when he sought public office for the first time. He went on to become a champion of states’ rights and the strict interpretation of the Constitution, especially in matters pertaining to slavery. When the war began, Davis was surprised he was elected to lead the new nation; he preferred a military appointment.

3. Both Suffered from Depression

It was called melancholia, depressions of the mind, and nostalgia, yet depression and other mental illnesses were beyond the understanding of early nineteenth-century medical science. Diagnoses and treatments were often faulty, and the most severe cases were simply referred to as madness.

Lincoln displayed telltale signs of clinical depression early. Friends and associates recalled his long bouts of debilitating sadness, which led some to consider him shiftless and lazy. Much of the prose and poetry he wrote throughout his life contained unrelenting self-criticism, a focus on miseries, and a preoccupation with death.

As much as Lincoln was and is celebrated as a rugged individualist honed by the backwoods of the American frontier, he hated his childhood. One of his first recollections was the sound of animals feeding on prey. He grew up loathing the process of hunting and fishing, found little joy in working the rocky fields, and lost nearly everyone close to him. Before Lincoln turned ten, his younger brother and mom had died. Before he was twenty his only sister passed away.

Still, depression came to form much of Lincoln’s behavior. To fight it, he employed his trademark wit, an iron commitment to privacy, and an often subtle but persistent ambition that fueled his success.5

Davis’s self-admitted struggle with depression emerged later in life. In his youth, little Jeff had a reputation as a dreamer and a prankster. At West Point, his fun-loving behavior cost him several demerits. Preferring to read classical literature rather than study the cold sciences of the curriculum, he graduated in the bottom half of his class.

After graduation, Davis’s physical health deteriorated. He suffered bouts of malaria (which killed his first wife, Sarah), pneumonia, anemia, boils, dyspepsia, bronchitis, rheumatism, angina, ear infections, tooth decay, a bullet wound to the foot (from the Mexican War), and facial neuralgia. The last caused crippling headaches and rendered one eye nearly blind. His physical and emotional pain often left him bedridden for weeks. Under doctor’s orders, he would sometimes take small doses of chloroform and opium to lessen the pain.6

Contemporaries of Lincoln and Davis who also suffered from enduring clinical depression included Mary Chesnut, Franklin Pierce, Samuel Clemens, William Tecumseh Sherman, Alexander H. Stephens, and Ulysses S. Grant.

4. Both Lost Sons Before and During Their Presidencies

Even during their most strained and serious moods, Lincoln and Davis were partial to the company of children, especially their own. Such a heightened fondness intensified their grief when they lived to bury two sons each. Lincoln’s second child, Edward, died of disease in 1850, just shy of a fourth birthday. Davis’s firstborn, Samuel, succumbed to illness only days before turning two in 1854. Loss would strike each man again during the Civil War.

William Wallace Lincoln was a prodigy. As a young boy he was gifted with the pen, a voracious reader, and possessed an exceptional long-term memory. In early 1862 Willie came down with fever, probably typhoid. After suffering for weeks, despite his parents’ constant care, Willie died on February 20, 1862. He was eleven years old.7

On April 30, 1864, Davis and his wife, Varina, were sharing a basket lunch in the second floor of the Confederate White House while their children played outside. Shortly after 1:00 p.m., a servant came running for the president. Five-year-old Joseph had fallen from the balcony, landing headfirst on the brick pavement twenty feet below. He was still breathing when his parents reached him. Joseph lasted only a few more minutes.

Accounts indicate both men repeated a phrase to himself on the day of his loss. Davis spoke of divine will while Lincoln lamented his son was “too good for this earth.” Each man allowed himself just one day of mourning before returning to work. Both men were visibly devastated for weeks and arguably scarred for life.8

Among others who lost children before or during the Civil War: Nathan Bedford Forrest, James Longstreet, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, and William Tecumseh Sherman.

5. Both Served in the U.S. Congress

Of the two, Davis’s pre-presidential résumé easily outweighed Lincoln’s. Elected to the House of Representatives in 1846, Davis resigned his seat to serve in the war against Mexico. Afterward his congressional and military records made him a popular choice as Franklin Pierce’s secretary of war. Elected to the nation’s upper house in 1860, Senator Davis resigned his seat once again, returning to seceding Mississippi in 1861. In a farewell address to his colleagues, he spoke of sincere hopes that his state and the other seceding states could leave the Union in peace.9

Lincoln served a single term in Congress, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. He spent much of his congressional energies attacking James K. Polk’s war with Mexico on the grounds that it was an unprovoked scheme to usurp land. Most of his fellow Whigs felt the same way. Lincoln and his constituents nevertheless approved the budget for the war’s continuation.10

In 1860 Jefferson Davis turned down an offer to run for president of the United States.

6. Neither Regarded African Americans as Equal to Whites

The owner of as many as one hundred slaves, the son of a slave owner, and the native of a state where half of the inhabitants were in bondage, Davis espoused the “moral good” of the institution. In Congress he called for the expansion of slavery into new territories and suggested Cuba, with its half-million slaves, was prime for acquisition.11

To the last, Lincoln was antislavery, not pro-slave. In one of the seven debates with political opponent Stephen A. Douglas, he continued to criticize slavery as a degradation of democracy and free labor. He added, however, “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” He vehemently opposed interracial marriages and African Americans holding public office, and he was skeptical of allowing minorities the right to vote or to sit on juries. Both publicly and privately, in the same vein as Thomas Jefferson, Lincoln called for the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for blacks as well as whites. Yet he also believed there existed unbridgeable differences between the two groups that would prevent them from ever living on the same social plane. In August 1862, a month before he announced his EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, he spoke with a group of free black leaders. Recolonizing outside the United States was the only path to peace for both races, he told them. “It is better for both of us,” he said, “to be separated.”12

In the 1870 elections, the man voted into Jefferson Davis’s vacated senatorial seat was Hiram R. Revels, the first African American senator in U.S. history.

7. Neither Asked to be Nominated for President

In the first century of American politics it was considered poor form to campaign for oneself. Appointments to public office were decided not by the individual but by his political constituency.

Before their party convention in 1860, Republicans at all levels began to take notice as a gathering host of newspapers promoted a coy but compelling stump speaker from Illinois. This fellow, many observed, possessed none of the abolitionist extremism, personal vices, nor prominent enemies of other potential candidates such as New Yorker William Seward or Pennsylvanian Simon Cameron. Lincoln did not request to be considered. His aspirations were for the Senate.13

The Republican National Convention was held in Chicago. With brilliant internal maneuvering, advocates and agents of Lincoln rode a wave of favorite-son sentiment to win nomination on the third ballot.14

Like Lincoln, Davis did not attend the convention that chose him, but he steered clear for very different reasons. In the spring of 1861 delegates assembled in Montgomery, Alabama, to select a provisional president for the new Confederacy. Meanwhile, Davis was at his Brierfield plantation in Mississippi, retired from politics with no ambition to return. He was, however, willing to organize Mississippi volunteers for military service should the need arise. Ironically, Davis’s display of patriotism and aversion to political gain impressed the convention considerably. They unanimously selected him as president. Although grateful, Davis later confessed that he was bitterly disappointed to have lost his chance to serve the Confederacy on the field of battle.15

Neither man chose his vice president. Lincoln had never met Maine’s Hannibal Hamlin before they were selected as running mates. Davis and Georgia’s Alexander H. Stephens were not allies before selected to serve together, and their differences intensified to hatred when the war went badly.

8. Both Condemned John Brown’s Raid

Nearly all whites in the South feared the possibility of a slave revolt. Nat Turner’s bloody 1831 uprising in Virginia, a rapidly expanding slave population, stories of slave riots in Brazil and Cuba, and the rise of radical abolitionism intensified the anxiety. In October 1859, when JOHN BROWN and a group of armed followers raided the Harpers Ferry arsenal, fear turned into outrage.

Initially, Davis joined the fury. From the Senate floor, he proclaimed the event “a murderous raid,” “a conspiracy,” and “a rebellion against the constitutional government of a State.” Had he been an extremist, Davis might have used the raid as a rallying point for Secessionists. After assisting in a senatorial investigation, he downplayed the incident. He noted there was no slave uprising. He also found no evidence of conspiracy. Davis concluded the raid was simply “an act of lawless ruffians, under the sanction of no public or political authority.”16

Lincoln, on the campaign trail for the Republican Party, attempted to depoliticize the event. Many Southern newspapers interpreted the raid as a product of Northern radicalism if not a failed full-fledged conspiracy headed by “Black Republicans.” Partial to the sanctity of law, Lincoln disapproved of Brown’s methods. Lincoln, however, knew he would lose much of his support base if he denounced Brown’s goal to end slavery. To save face, he attacked the man rather than the mission, publicly reiterating a hatred for slavery while dismissing Brown’s raid as an act of “violence, bloodshed, and treason.”17

John Brown asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass to assist in the raid. Tubman accepted the invitation then declined due to illness.

9. Both were Political Moderates

It is one of the great ironies of American history. In a time of political, economic, and social breakdown, when national passions and differences were at their highest intensity since the Revolution, the opposing sides chose moderates to lead them.

After the Democrats split into Northern and Southern factions before the 1860 presidential elections, Davis attempted to reunite the party, going so far as to ask the presidential nominees from both sections to withdrawal from the race. A compromise candidate, such as New York governor Horatio Seymour, Davis insisted, would be the only way to defeat the Republicans and maintain the Union.18

While his contemporaries warmed to the idea of secession, Davis opposed it. Much like his mentor JOHN C. CALHOUN, Davis threatened secession several times in Congress. He also knew, as Calhoun did, that leaving the Union meant losing Southern leverage within it. A separate South would have no say on tariffs, no chance to retrieve fugitive slaves in the North, and no share of the Union’s growing economic power.19

After the Union fell apart, Davis took no part in the Confederate Convention. When the convention chose him to be the provisional president, they did so on the grounds that Davis had effectively distanced himself from fire-eaters and other political extremists. Even as the new country worked to select a new flag and create a new Confederate Constitution, Davis suggested that the old flag and constitution would work just fine.20

Lincoln functioned on the principle that a radical stand left him no room to maneuver. He consistently placed himself in the center of divergent groups, a fact most prevalent during his presidency. His cabinet consisted of several political opponents. In military appointments, he granted lofty positions to ardent Democrats as well as Republicans. Historically viewed as the Great Emancipator, he refused to court the idea of ending slavery during the first year of the war. When political and military circumstances encouraged him to issue his EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, he made no attempt to abolish slavery within the four slave states still loyal to the Union. In the 1864 election he ran under the combined Republican-War Democrat banner of the National Union Party and accepted as his running mate Andrew Johnson, a lifelong Democrat from Tennessee.21

“Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can.” —Abraham Lincoln

10. Both were Accused of Wearing Dresses

A president can make an easy target for accusations, especially in times of uncertainty. Sometimes criticism stepped beyond abuse into the bizarre.

In February 1861 president-elect Lincoln traveled from Springfield to Washington by rail. To reach the capital meant passing through slave state Maryland. Lincoln had received dozens of assassination threats before and during the trek, and several sources suggested an attempt would be made on his life when he changed trains in Baltimore.22

Rather than risk altercation, Lincoln chose to pass through in the middle of the night. To conceal himself further, he wore a loose overcoat and soft wool cap. His stealthy entry into Washington only strengthened criticism, however, and some portions of a hostile press interpreted the coat to be a woman’s frock. Lincoln was accustomed to opposition, but accusations of cross-dressing were rather new.

At the other end of the war, Jefferson Davis had become a convenient scapegoat. Just before Richmond fell, Davis and a small contingent sped southward by horse and wagon. Labeled a coward, Davis intended to link up with any remaining Confederate forces to continue the fight for as long as possible.

On May 10, 1865, Davis, his wife, and two others encountered Federal troops near Irwinville, Georgia. Hearing the approaching cavalry, Davis accidentally put on his wife’s sleeveless overcoat, one very much like his own, and wore it underneath a shawl as he attempted to reach his horse. The Federals caught him soon after, overcoat and all. A vilifying rumor mill tailored the story into one involving a full-fledged dress.23

In 1861 a wool dress cost ten Confederate dollars. By 1865 rampant inflation pushed the price up to eight hundred Confederate dollars.

The erroneous report that Davis had been captured disguised as a woman provided ample fodder for many newspapers.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE CONFEDERATE AND U.S. CONSTITUTIONS

March 11, 1861—Members of the Montgomery Convention, having assembled the previous month to declare the formation of a new country, rose one by one to give their final vote on the Constitution of the Confederate States of America. Represented were six states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. Also present were delegates from newcomer Texas, which had finalized secession just ten days earlier.

Together there were fifty delegates. All were male, white, formally educated, roughly middle-aged, and experienced in civil service. Many were still fond of the old Union, notable exceptions being fire-eaters ROBERT BARNWELL RHETT of South Carolina, thomas r. r. cobb of Georgia, and louis t. wigfall of Texas.24

Starting with an ad hoc provisional constitution, the convention worked to create a permanent version, first by a committee of twelve and then through debate from the assembly as a whole. Several delegates were encouraged if not ordered by their state conventions to adhere closely to the Federal Constitution. To roam far from the original, they feared, would give the impression that this new movement was seditious and fanatical. Also, there was no time or need to reinvent something that had served them so well. Only Northern manipulation of the original Constitution, argued the Secessionists, had caused so much consternation. In what should have been seen as foreshadowing, no one seriously considered returning to the Articles of Confederation of 1777, a political experiment that floundered from disunity.25

Despite fueling angry exchanges between the delegates, the final draft received resounding approval. The convention, it appears, wished to present to the country and the world a united front. The end tally was unanimous; all fifty delegates voted to adopt the new constitution. From beginning to end it took them thirty days, less than half the time required for the creation of the one it replaced.26

Following are the top ten most significant areas in which the Confederate Constitution differed from its Federal counterpart in terms of the degree of departure and its eventual consequences on the operations of the Confederate political enterprise.27

The Confederate Constitution of 1861…

1. …Expressly Defended the Right of Slavery,

Slavery nearly derailed the Constitution of 1787. Slave and free states could not agree on the inclusion or exclusion of slavery for the country as a whole. Eventually, the Philadelphia Convention used the ambiguous term “other Persons” rather than “slaves” and delayed final decision on the institution’s fate, hoping future generations could peacefully resolve the issue.

Montgomery was not Philadelphia. Of the fifty-five members of the Philadelphia convention, 25 percent owned people. Of the fifty members of the Confederate convention, 98 percent were slave owners (although less than 30 percent of white males in the South owned slaves in 1861). Forty-eight of the fifty men were born in slave states, and thirty-three stated their profession to be “planter.” Guarantees they had requested time and again from the old Union could now be attained without opposition.

When determining the number of representatives to be apportioned per each state’s population, the Confederate version altered the infamous “three-fifths of all other Persons” clause to read “three-fifths of all slaves.”

The Confederate Constitution also retained the ban on international slave trade, much to the disappointment of ROBERT BARNWELL RHETT and a handful of others. The convention knew that to repeal the clause would eliminate any chance of international recognition from antislavery Great Britain and France, and yet the convention replaced the phrase “other persons” with “negroes of the African race.”28

In protecting a citizen’s rights from state to state, the Confederate version added “the right of transit and sojourn in any State of this Confederacy, with their slaves and other property; and the right of property in said slaves shall not be thereby impaired.” There also emerged a strengthened fugitive slave law, pledging the return of slaves “escaping or unlawfully carried” into another state or territory back “to whom such service or labor may be due.”29

Concerning the future acquisition of any new territories (conceivably from Mexico, Cuba, or parts of Central and South America), the Confederate Constitution stated, “In all such territory the institution of negro slavery,…shall be recognized and protected by Congress,” a provision powered by memories of Bleeding Kansas and the split of the Democratic Party over popular sovereignty.

Slavery was to be legal, protected, and enforced everywhere and in every state and territory to come. An irony existed that some may have seen but no one argued: In a movement founded on states’ rights, no state had a right to infringe upon the institution of slavery.

Absent from the U.S. Constitution, the terms “slaves” or “slavery” appeared in the Confederate Constitution ten times.

2. …Outlawed Nearly All Internal Improvements,

The concept of internal improvements vexed many nineteenth-century citizens, as it still does today. How was it right and just to take funds raised in one portion of the country and use it to finance projects in another? Young politicians from the developing West, like Abraham Lincoln, supported the policy. Most Southern politicians hated the idea. Rural and agrarian, the South simply did not have the fiscal appetite or the infrastructure requirements of the more urban and industrialized states to the North.30

In the old Union there wasn’t much the Southern states could do. Much like decisions concerning slavery, decisions on appropriations were destined to be predominantly unfavorable to the South if done on a national level, because the South simply did not have the votes. In 1820, slave states had lost a majority in the House of Representatives. By 1850 parity in the Senate was gone, with no indication of equaling again.

For their decades of fighting against internal improvements, the delegates still could not eliminate the practice from their new constitution. Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 3 stated the Confederate Congress could not “appropriate money for any internal improvement intended to facilitate commerce; except for the purpose of furnishing lights, beacons, and buoys, and other aids of navigation upon the coasts, and the improvements of harbors.”

In 1853 the U.S. Government bought a tract of land from Mexico for $10 million in order to build a transcontinental railroad. The orchestrator of the Gadsden Purchase was Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

3. …Deleted the Term “General Welfare,”

From the preamble, the Confederate committee of twelve omitted “provide for the common defense” and “promote the general Welfare.” The term “general Welfare” was also stricken from Article 1. The old preamble, reasoned the delegates, invited the central government to override the best judgments, interests, and inherent responsibilities of the states.

Intentionally provincial in their rationale, the omissions were also anti-egalitarian in principle. The Southern “way of life,” so often celebrated in Secessionist arguments, revolved around a kind of benevolent paternalism, where supposedly no one but wise men of education and property knew how to serve and provide for the remainder of the population. In an effort to dilute concepts of equality still further, there were motions to strike the words “We the People” from the document, a stance that was summarily dismissed as too extreme.31

How strong were “the People” in the new Confederacy? Unlike the Federal version, the Confederate Constitution had “people” typeset in lower case.

4. …Outlawed Protective Tariffs,

Of all the perceived threats upon Southern economic integrity and political honor, the most real was arguably the federal use of tariffs—the artificial increase of prices on foreign goods to protect domestic manufacturing. Many Southerners considered tariffs pointless, because the agrarian South had no great manufacturing interests to protect. More important, the South’s cash-poor economy could ill afford to pay higher prices for imported items. Nearly every yard of cloth, section of rail, plowshare, pill, pistol, and locomotive in the South came from somewhere else.32

Tariffs also stunted Southern industrial growth, as they increased the costs of drills, belts, boilers, bearings, and other basics required for transition from manual to mechanized production. The Confederacy would have none of that. In creating free trade, the convention hoped that the South would have an open and relatively inexpensive lifeline to Britain and France.

Unfortunately, as the Confederacy eventually learned, ceasing protective tariffs also liberated the Confederate government from the beefy revenues that came with them. During the war years the Union raked in more than $300 million from protective tariffs. Strangled by the blockade and unable to tariff much of anything, Confederate customhouses raised less than $4 million.33

In 1832 South Carolina threatened to secede from the United States, not over slavery, but over the federal imposition of high import tariffs.

In 1861 one Northern state and one Southern state had line-item vetoes available to their governors. The Confederate Constitution adopted the policy, empowering the presidency to reject any portion of a prospective bill the executive deemed unwarranted.

The ease with which this provision gained acceptance reflected a fiscal skepticism among the delegates. Of the fifty members, forty-five had experience in state legislatures and twenty-three had served in the U.S. Congress. Many had witnessed pork-barrel issues and questionable rider projects attached parasitically to legitimate legislation.

Veto is Latin for “I forbid.”

6. …Dictated a Single Term for the President,

George Washington declined to run for a third term, setting protocol for a self-imposed term limit for chief executives. No legal foundation existed, however, for a president to stop at two. With a collective suspicion of centralized power, the Confederate Convention imposed, “He and the Vice President shall hold their offices for the term of six years; but the President shall not be re-eligible.”

History hardly justified much concern. A majority of presidents before Lincoln hailed from the South, eight owned slaves during their presidency, and most were sympathetic to Southern interests. Longevity was not an issue, as the last eight presidents all served four years or less, due in no small part to their respective inability to calm the rough waters of sectionalism.

Yet all seven states in the convention seceded from the Union because a section of the country elected a president they did not want. This was not a group ready to take a chance on any president’s ruling for long.34

The issue of duration was eventually invalidated by fortunes of war. Apparently, the Union army and navy were also interested in limiting the Confederate presidency to a single term.

The Twenty-second Amendment added a presidential term limit to the U.S. Constitution—ninety years after the Confederate Constitution stipulated such.

7. …Overtly Mentioned God,

The phrase appeared in the Confederacy’s provisional constitution, “invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God.” The wording survived without opposition through committee and convention to appear in the preamble of the final document.

Spiritual language was nothing new in American politics. The Declaration of Independence referred to “Nature’s God,” the “Supreme Judge of the World,” and “a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence.” In the fight over slavery, defenders quoted Bible passages and opponents spoke of a law higher than the U.S. Constitution. Each session of the U.S. Congress began with an official prayer (as it still does).

Yet to include a reference to “Almighty God” into the supreme law of the land was something the original Founding Framers refused to do. The men of the Philadelphia Convention recounted medieval Rome, Bourbon France, a certain King George III, and other tyrannical regimes that claimed power by divine right. From the quills of James Madison and Thomas Jefferson came eloquent pleas for religious tolerance and an enduring separation of church from government.35

By comparison, the men of the Montgomery Convention wished to appear more evangelical in their sentiments. The image desired was that of a system still based on the mechanical logic of checks and balances but standing firm and righteous against a secular and heartless enemy.36

The national motto of the Confederacy was Deo Vindice—“God will avenge.”

8. …Eased the Process of Amendments,

Changes can be proposed to the U.S. Constitution by a two-thirds approval from the House and the Senate, or by two-thirds of the states calling for a convention. Passage requires ratification by at least three-fourths of all states.

In a compromise between the hard-line states’-rights faction and the conservative element, the Confederate Constitution allowed an amendment to be considered if only three separate state conventions called for one. In addition, the three-fourths provision for ratification was reduced to two-thirds.

In the end, easing of the amendment process had little effect on the Confederacy, as it did not live long enough to change its national law.

All twelve amendments then existing in the U.S. Constitution were incorporated into the main Articles of the Confederate Constitution.

9. …Stipulated a Self-Sufficient Post Office,

Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 7 dictated “the expenses of the Post office department, after the 1st day of March in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and sixty-three, shall be paid out of its own revenues.” The establishment of post offices also existed in the U.S. Constitution, but there was no accompanying stipulation to operate in the black. Robert Toombs of Georgia introduced the idea in committee, and WILLIAM PORCHER MILES of South Carolina added the two-year time limit in convention.

The postal clause came from a political body fully aware that money and time were two luxuries it did not possess. Revenues were expected to be scarce. There was no national income tax. The convention omitted protective tariffs, cutting off a certainly unpopular but financially helpful source of capital. The Southern Confederacy had been born from a comprehensive distaste for fiscal intrusions, yet such intrusions were sorely missed once the financial costs of warfare began to accumulate.

A self-sufficient Confederate post office was in fact achieved in less than two years, but in the effort to keep costs down, the service became notoriously unreliable.

10. …And Declared Supremacy of State over Central Government.

From the 1830s onward, the resounding chime of states’ rights rang warm in the hearts of an increasing number in the South. It long stood as a popular expression, a default response to any unfavorable decision made by the federal government. By 1860, after bloody fights over territories, national elections, and fugitive slaves, the appeal had reached much of the Southern free population.37

Moved to maintain this sanctified message of “states first,” the convention began the defining document with “We the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character.”

For all the hope and glory of state supremacy, the means were largely absent from the Confederate Constitution. The president remained commander in chief of the army, navy, and state militias. Also, the president could attain the right to suspend habeas corpus (a right the Congress granted Davis early in the war). As stated above, the executive held the power of a line-item veto. Although never implemented, Article 1, Section 7 permitted members of the president’s cabinet to hold seats within either of the congressional houses, a clause designed to offer leverage for defense of executive measures. Minting coins, forming treaties, regulating weights and measures, naturalizing citizens, plus setting and collecting levies were still in the hands of the central government and not the states.

The Confederate Constitution also replaced the idealistic phrase, “a more perfect Union,” with the pragmatic assertion, “a permanent federal government.” This suggested a centralizing rather than a confederating theme. By some interpretations the change also implied that the right to secede was an option in the Union but not in the Confederacy.38

For all the supposed clarifications and favorable alterations to this new Constitution, reality had its own purposes. Out of the frying pan and into the fire, the seceded states soon squabbled over the same issues of rights and sovereignty within the Confederacy as they had within the Union.39

There was a modicum of discussion within the convention to name the new country something other than the Confederate States. Suggestions included Chicora, Columbia, the Federal Republic of America, the Southern United States, the Gulf States of the Confederacy, Alleghenia, and Washington.

It can be said that none benefited more from secession than the Republican Party. A division of the country also divided the Democrats, who usually held the presidency and dominated the House and Senate by large margins. Over the span of the war, Republican bills passed that would have never seen the light of day had the Southern balance remained.

Alternately, the Confederate Congress struggled tremendously. The growing pains of governance, the crippling lack of revenue, and the destabilizing force of an invading enemy created a need for a powerful centralized government—the very situation Secessionists claimed they were leaving behind. To make matters worse, if the Confederacy were to fail, Southerners in and out of politics knew what was in store. They would reenter a Union far more centralized and Republican than the one they had left.

In addition to the Internal Revenue Act, Legal Tender Act, and Conscription Acts (listed in top ten firsts), the following were the most significant acts of government in domestic politics. These ten have been selected for their effect on the direction of the war and their lasting influence on the country as a whole. They are listed in chronological order of implementation.

1. Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus (U.S., April 27, 1861)

“To produce the body,” or the writ of habeas corpus, is a long-standing pillar of English common law. Without it, citizens could be incarcerated without charges, evidence, or trial. Both the U.S. and Confederate Constitutions permitted suspension of the writ in times of “Rebellion or Invasion.”

Lincoln suspended the writ immediately. With his capital resting south of the Mason-Dixon Line and bordered by Confederate Virginia and slave state Maryland, he ordered a suspension for the Philadelphia and Washington areas. In 1862 he issued another abeyance for all arrests conducted by the military. In 1863 Congress authorized the suspension for the whole of the Union.

In February 1862 the Confederate Congress granted Davis similar powers. Denying an extension in 1863, legislators gave a limited renewal of Davis’s authority in February 1864.40

Under the suspension, government officials could and did seize citizens suspected of espionage, draft evasion, inciting insurrection, desertion, trading with the enemy, and guerrilla activities, with and without evidence. Of the two sides, the Union suspended the writ with greater impunity, making an estimated fourteen thousand arrests over four years, mostly within the border states.41

Throughout the war both presidents endured a steady stream of criticism for suspending the writ, with accusations of power mongering, abusing civil liberties, and vying for permanent dictatorship. Yet Lincoln and Davis actually discouraged suspension of the writ in cases of speech, press, and assembly.42

When Chief Justice Roger Taney protested the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, Lincoln briefly considered arresting the chief justice.

2. Confiscation Act (U.S., August 6, 1861)

Between his election and inauguration, a span of just four months, Abraham Lincoln watched seven states leave the Union. After the surrender of Fort Sumter, four more departed: Virginia in April, Arkansas and North Carolina in May, and Tennessee in June. July brought a military beating along the banks of Bull Run. Four slave states still remained, and Lincoln was willing to do almost anything to keep them from joining the Confederacy. This included upholding the Fugitive Slave Law, which mandated federal cooperation in returning runaways to their owners. His adherence to the law incensed abolitionists and militarists alike.43

Forcing the issue were the slaves themselves, escaping to Union lines by the hundreds. If he instructed officers to hold on to them, Lincoln risked losing the last four slave states in the Union. If he handed the slaves back, he could surrender his base of support among free states and possibly Europe.

Republican-led Congress offered a compromise in the Confiscation Act of 1861. Slaves used by the Confederate army—for example, in the construction of forts—could be seized as property used against the Union. All other escapees would be returned.

Congress passed a second confiscation act on July 17, 1862. Along with authorizing the seizure of land and resources of those supporting armed insurrection, the act also granted freedom to slaves escaping from inside Confederate-held areas, unless their owners were loyal to the Union. Five days after the bill passed, Lincoln began a rough draft of a proclamation to emancipate all slaves in enemy territory.44

Of the 179,000 African Americans who served in the Union army, more than half came from the slave states of Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

3. Homestead Act (U.S., May 20, 1862)

Although a bill had been in the works for decades, legislation to provide government land to settlers was extremely unpopular among Southerners and, understandably, Native Americans. President James Buchanan vetoed a version in 1860, suggesting it was unwise to give away land at no cost. Yet Republicans included the idea in their party platform.

Effective opposition left with secession, and the U.S. Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862, restricting entitlement to those who had “never borne arms against the United States Government or given aid and comfort to its enemies.” Citizens could gain ownership of designated public land up to 160 acres, provided they live on and “improve” that land for five years and pay a ten-dollar fee for the paperwork.45

The act was an early form of welfare and simultaneously garnered votes and fueled rapid expansion into the Dakotas, Michigan, Minnesota, and Missouri. By 1864, with the law not yet two years old, settlers had claimed more than one million acres.

Through the Homestead Act a half-million settlers eventually received eighty million acres, an area of land more than twice the size of New York State.

4. Pacific Railway Act (U.S., July 1, 1862)

For a dozen years the federal government surveyed, debated, and coveted plans for the creation of a rail line from the Mississippi to the land, ports, and gold of California. Agreeing on the destination, Congress naturally had a division over the point of origination, and each region had valid points for arguing why it should be the eastern terminus. The North possessed a majority of the people, money, and industries, including a virtual monopoly on the production of rail iron and steam engines. The South owned the dual monarchy of King Cotton (the most lucrative U.S. crop) and the River Queen (New Orleans as the largest city west of the eastern seaboard). Of course this competition ceased with the outbreak of war.

Begun in 1862 and completed by 1869, construction of the Pacific Railway cemented Northern domination of commercial traffic, facilitated the reduction of bison herds from millions to a few thousand, and made hinterland California a prominent and populous state in a matter of years. Along with these and many other dramatic changes, Section 2 of the act foreshadowed the continuation of a known pattern: “The United States shall extinguish as rapidly as may be the Indian titles to all lands falling under the operation of this act.”46

In a show of patriotism, the corporation formed to lay down this track was named the “Union Pacific Railroad Company.”

5. Land-Grant Act (U.S., July 2, 1862)

Prior to the Civil War the best engineering colleges in the country were military schools. Students usually sought entry to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and the Virginia Military Institute for a degree in applied science. Few wanted an army career, which often consisted of frontier duty, meager pay, and little chance for promotion. Opportunities for enrollment into these schools, however, were extremely limited.

The 1862 Land-Grant Act (introduced by Congressman Justin Morrill of Vermont) offered a fundamental change in the access and application of higher learning. For every senator and representative a state possessed, a state would receive thirty thousand acres of public land. States were to use or sell this land to establish and maintain schools of industrial, agricultural, and mechanical engineering. Most of the property was in the West, whereas most of the people were in the East. Thus the act was a lopsided arrangement indeed, but it eventually proved beneficial to the whole country, including the states temporarily detached from the Union.

Of limited effect during the war, the Morrill Act eventually made higher education available to the lower economic strata. Places such as Cornell and Ohio were joined after the war by Mississippi State and Texas A&M. Nearly 150 years later, more than 100 schools are commonly referred to as land-grant colleges.47

The 1862 Land-Grant Act stipulated the inclusion of classes in military tactics and strategy. These campus courses evolved into what is now known as ROTC.

Lincoln began work on the Emancipation Proclamation during the summer of 1862. He shared it with his cabinet in late July, and the members advised that he not publish it until the Union army had won a substantial battle.

6. Emancipation Proclamation (U.S., January 1, 1863)

Motivated by a growing public antagonism toward slaveholding, and seeking a way to reduce international sympathy with the Confederates, Lincoln wrote a preliminary emancipation proclamation in July 1862. Members of his cabinet suggested he wait until a Union military victory allowed him to present the proclamation from a position of strength. When the Army of the Potomac scored a close win at the battle of ANTIETAM, Lincoln made his declaration public.48

Observers in the South and Europe regarded the edict as an attempt to incite slave uprisings. Jefferson Davis labeled it “the most execrable measure in the history of guilty man.” The LONDON TIMES was a little more vivid in its rebuke: “When blood begins to flow and shrieks come piercing through the darkness, Mr. Lincoln will wait until the rising flames tell that all is consummated, and then he will rub his hands and think that revenge is sweet.”49

Perhaps half of the Union supported the proclamation, a fourth were against, and another fourth were in between. Over time however, as Union soldiers witnessed more and more of slavery, and Northern civilians sought ways to ennoble a costly war, public backing gradually increased.50

The proclamation did not free a single slave, referring only to slaves in “states and parts of states wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion.” To help bring these areas back into the Union, the proclamation included a passage declaring freed blacks “will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”51

For slaves not in areas of rebellion, Lincoln was less generous. In December 1862 he advised Congress to create a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery in the loyal states by the year 1900.

7. Tax-in-Kind Measure (C.S., April 24, 1863)

Hesitant to tax their constituency, the Confederate Congress eventually found the government chronically short of funds and withering under inflation. To make up ground, the legislature enacted a comprehensive tax plan in 1863, hoping to put Richmond and the war effort back on stable economic footing.

The plan was rather abrupt, taxing alcohol, flour, rice, sugar, tobacco, and wool. Citizens were subject to income taxes and sales taxes up to 10 percent. Taxes were also to be levied on a myriad of professional licenses. Worst of the lot was a tax-in-kind measure, authorizing the government to seize 10 percent of all farm products.52

Designed to resolve food and supply shortages, the tax-in-kind levy worsened them. An army of three thousand government collection agents scoured the countryside, arbitrarily determining what constituted 10 percent of a family’s animals and crops. In response, farmers hid their harvests or sold them on the black market. Much of what was confiscated never made it to the intended recipients. Storing and transporting acquired goods proved to be excessively complicated, leaving untold tons of bacon, corn, peas, and beef to rot in depots.53

For their title and tactics, Confederate tax-in-kind agents were unceremoniously referred to as “TIK men.”

8. The Thirteenth Amendment (U.S., January 31, 1865)

The House and Senate passed a Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in February 1861. Had it been ratified, it would have prohibited any federal obstruction of slavery within the states. Nearly four years later a very different Thirteenth Amendment entered the House and Senate for consideration.

Introduced by Republican leaders in 1864, the brief clause stated: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Passing easily in the Republican-dominated Senate, heavy Democratic opposition in the House left it well short of the required two-thirds majority.

In the November elections Lincoln retained his office, and his party made huge congressional gains. With impending dominance over government contracts and civil service opportunities, Lincoln and his associates convinced lame-duck Democrats that it was in their best interest to support the measure. On January 31, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment passed with three votes to spare. Thunderous applause swelled throughout the chambers and lasted unbroken for several minutes. The recently finished Capitol dome shuddered as nearby batteries fired a hundred-gun salute.54

By December 1865 the required three-fourths of all states (including eight of eleven former Confederate states) ratified the amendment, removing slavery from the Constitution and the country.55

The war lasted forty-eight months. The Thirteenth Amendment consists of forty-eight words.

9. Negro Soldier Bill (C.S., March 1865)

African Americans were serving in the Union navy by September 1862. Through the EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION and other measures, recruitment into the army was in full swing by early 1863, although freedmen had tried to volunteer since Fort Sumter.56

A complicated affair for the North, arming blacks was a nonissue for the South, until attrition depleted Confederate ranks to the breaking point. As early as January 1864, Gen. PATRICK CLEBURNE openly endorsed the idea of turning slaves into soldiers. Jefferson Davis rejected the proposal without hesitation. But by November 1864, speaking before the Confederate Congress, Davis himself reluctantly suggested discussion on the matter. In Congress, among the press, and from slave owners, opposition was overwhelming.57

In the following months, support for a Negro Soldier Bill grew steadily, including an endorsement from a long silent robert e. lee. Still, the measure died in the Confederate Senate by one vote. Only Virginia, acting on its own behalf, passed a bill authorizing the formation of slave regiments.58

In the end, the effect was minimal. Virginia managed to form only a few poorly armed companies. Richmond fell before they could be sent into action. Yet the debate over the Negro Soldier Bill was an unintentional compliment to the slaves themselves, suggesting the Confederacy could not survive war or peace without their help.

In February 1865 Jefferson Davis received petitions supporting the enlistment of slaves into the Confederate army. The petitions came from Confederate soldiers stationed in the trenches of Petersburg.

10. Amnesty Proclamation (U.S., December 25, 1868)

There was no definitive end to the Civil War, no peace treaty, no Armistice Day to speak of. For all intents and purposes, the life of the Confederacy had reached its end with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. Joseph E. Johnston, however, did not officially surrender his emaciated Army of Tennessee until April 26. There was one last battle, on May 13 at Palmito Ranch, Texas—a Confederate victory.

Political milestones were just as inconclusive. Jefferson Davis was not captured until May 10, 1865. In 1870 Georgia was the last Confederate state readmitted into the Union. Federal occupation of the South did not end until 1877.

A frequently cited termination point is President Andrew Johnson’s granting a general amnesty on Christmas Day 1868. Johnson’s days in the White House were coming to an end. So as to go out in a favorable way, he would “hereby proclaim and declare unconditionally, and without reservation, to all and to every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late insurrection or rebellion, a pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason against the United States.”59

For radical Republicans taking a hard-line approach to reconstructing the South, this was one more instance where Johnson was “soft on sedition.”

When eleven Confederate states seceded, all of their U.S. senators resigned their seats, with the exception of a Unionist from Tennessee, Andrew Johnson. He remained loyal to the Union throughout the war and thus was rewarded with the vice presidency.

Although not a world power in the nineteenth century, the United States was a rising force. Having bettered the British Empire in the Revolution and the War of 1812, taken half of Mexico in 1848, and opened the ports of isolationist Japan in 1854, little seemed to stand in the country’s way. Consequently, the potent newcomer surprised much of the world when it suddenly appeared to crumble apart.

Far from occurring in a vacuum, the war in the United States was very much a multinational affair. Many American farms, railroads, plantations, mills, and banks ran on international investment. Nearly a quarter of the continent was foreign born or second generation. The American Revolution succeeded largely because of foreign intervention. If the Civil War turned into a stalemate, international relations could decide the outcome.

In chronological order, the following were the most significant transnational episodes of the war. Not surprisingly, these events involved the usual modes of international intrigue: smuggling, coercion, begging, and threats.60

1. The Confederate Quest for Diplomatic Recognition (April 1861–March 1865)

Jefferson Davis and much of the South assumed that, sooner or later, France and Britain would officially sanction the Confederacy. The European powers encouraged this assumption by declaring the Confederacy a belligerent—a de facto government engaged in a war that was not illegal. Such a declaration was one step shy of granting de jure status—complete diplomatic recognition of the government as sovereign and independent.61

Brimming with confidence, Davis was somewhat careless in selecting his diplomats. First to head the Richmond delegation was temperamental, uncouth, slave-owning, fire-eating WILLIAM LOWNDES YANCEY. Surprised by his inability to gain European approval, Yancey complained, “The antislavery sentiment is universal. Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been read and believed.” In September 1861 he resigned and headed home.62

His replacements, John Slidell and James Mason, fared little better. Reluctant participants in the TRENT AFFAIR, the two diplomats possessed neither the charisma nor the diplomatic ingenuity required to sway their hosts. In all fairness, factors of greater significance worked against them.

Napoleon III of France was nearly indifferent to the American problem, and he would make no move to recognize the Confederacy unless Britain moved first. No fans of the United States, Britain’s prime minister Lord Henry Palmerston and foreign minister Lord John Russell were nonetheless lifelong veterans of public service. Despite bouts of nationalist rhetoric and saber rattling, the two were committed to “wait and see.”

What they saw was a British public remarkably pro-Union. As much as the LONDON TIMES promoted the Confederacy, the London Economist, Edinburgh Review, and others were virtually anti-South. English bankers and businessmen held interests in Union shipping, railways, and factories. The working poor had little sympathy for “Slaveownia.” For many Britons, they had their own empire to run, and there was little interest in provoking the wrath of America once again.63

The biggest block to recognition was the intermittent success of the Union army. Palmerston and Russell were considering mediating an end to the war when the Army of the Potomac edged the Confederates in the battle of ANTIETAM. Lincoln’s following EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION brought slavery to the forefront of the discussion, an institution Britain disdained even more than the pesky United States. In the summer of 1863 mediation again came under consideration until the Union appeared destined for eventual success after victories at GETTYSBURG and VICKSBURG. That August the Confederate Secretary of State JUDAH P. BENJAMIN all but gave up on foreign recognition, and so did pro-South politicians in Britain.64

Reportedly, only one nation ever diplomatically recognized the Confederacy: the German Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

2. The Blockade (April 1861–April 1865)

In April 1861 Lincoln declared a “blockade” of Southern ports. His verbiage surprised foreign merchants and public officials. Under international law, a country blockades another country, it closes its own ports. For a man normally careful with his declarations, Lincoln had, in so many words, recognized the Confederacy as an independent nation.65

International law also considers a blockade legal only when it is effective, that is to say, when “might makes right.” At the time of Lincoln’s statement, the Union navy consisted of only a few dozen functioning ships, many of them stationed in far-off waters. The Confederacy had thirty-five hundred miles of coastline, ten major ports, and hundreds of inlets, sounds, and bays. For months private vessels both foreign and domestic continued to pierce the Union’s quarantine. Lincoln appeared to be losing both a military and a legal battle.66

Yet armed with a superior industry and led by industrious Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, the Union began to achieve success on the waters. By late 1862 the Union had more than four hundred ships and twenty-eight thousand men monitoring Southern shores. In opposition the Confederacy mustered just thirty armed vessels and a few thousand sailors.67

For adventurous merchants, blockade running turned from a sport to a pitfall. In 1861 only one of ten runs failed. By 1865 the U.S. Navy caught half of all departures, convincing foreign navies to shy away from intervention. In the end, might did make right.68

Among the Confederate blockade-runners was a lightning-quick sailing ship called America, winner and namesake of the first cup race in 1851.

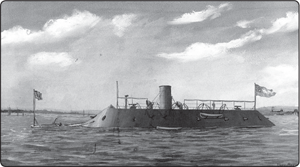

CSS Virginia was designed first and foremost to break the Union blockade.

3. British Manufacture of Confederate Cruisers (June 1861–September 1864)

By the end of June 1861 France, Britain, and Spain declared neutrality toward the Civil War. This declaration permitted the selling of arms and ships to belligerents under international law. Immediately the Confederacy contracted British shipbuilders to construct seafaring cruisers.

British law, though, forbade selling armed ships to belligerents. Builders sidestepped the restriction by constructing unarmed cruisers, taking them out on “test runs” in open waters, then equipping them with weaponry in the Azores or the Bahamas. The Confederacy received some eighteen cruisers in this fashion.69

Designed to seek and destroy Union merchant vessels, three of these seagoing raiders were conspicuously lethal. The CSS Florida captured or sank thirty-six commercial ships, the CSS Shenandoah another forty, and the CSS Alabama an astounding sixty-six before being cornered and sunk near Cherbourg, France.70

U.S. citizens lost millions of dollars in ships and cargo. Insurance rates and import prices rocketed. Shipping companies refused service or sailed under foreign flags. Under the definition of “high seas,” “belligerents,” and “warfare” in international law, the Confederate raids were all above board.

Despite fervent efforts from its navy, the Union failed to stop the Confederate raiders. Nevertheless, the government did sue Britain for damages. In a landmark case, arbitrators finally settled the Alabama claims in 1872, awarding the U.S. government $15,500,000 in British gold.

While raiding ships in the Pacific, the crew of the CSS Shenandoah did not hear of its country’s defeat until August 1865—four months after the fact. The crew surrendered the vessel in Liverpool, England, on November 6, 1865.

4. The Cotton Embargo (September 1861–April 1865)

The plan seemed simple enough. Much of Britain’s industry and exports involved processed cotton, and more than 70 percent of its raw cotton came from the southern United States. If Britain lost access to its white fiber, reasoned many Southern lawmakers, the British Empire would have to intervene on behalf of the South or face economic implosion.71

To speed up the process, Richmond discouraged farmers from growing cotton. Planters converted their fields to other crops. Some state and local governments made it illegal to grow or sell the staple altogether.72

Ultimately, a multitude of conditions torpedoed the plan. First, the 1860 harvest was one of the best ever, and British warehouses were filled with the surplus. Even as stocks dwindled and factories shut down, the laboring poor of England backed the Union cause, blaming the shortage on the aristocratic Confederacy. By 1863 new supplies came in from Egypt, India, and Brazil as well as several tons smuggled out of the South. Last but not least, much of Britain saw the self-imposed embargo as blackmail, a tactic they found less than palatable. Historian Charles Hubbard poignantly observed that, in the end, no one was more dependent on cotton than the South.73

In 1860 the number-one U.S. export was cotton. By 1862 cotton exports were at 2 percent of prewar levels.

5. The Trent Affair (November 1861–January 1862)

On November 8, 1861, Capt. Charles Wilkes of the USS San Jacinto captured and detained two men from the mail steamer Trent off the coast of Cuba. Neither pirates nor sailors, the men Wilkes seized were former U.S. Senators John Slidell of Louisiana and James Mason of Virginia—two Confederate envoys on their way to seek diplomatic recognition from Britain and France.74

The Northern public celebrated the great catch, Congress gave Wilkes its official thanks, but Lincoln worried. Forcibly removing passengers from an unarmed ship in international waters was a blatant disregard for international law. The United States went to war with Britain in 1812 over such high-seas impressment.75

Lincoln’s fears proved warranted. When the British government heard of the capture and the ensuing celebrations in the North, an already volatile anti-American lobby in Britain called for war.76

The British cabinet under Lord Henry Palmerston demanded the immediate release of the prisoners, payment of reparations, and a formal apology. More than eleven thousand British troops were dispatched to Canada. Likewise, hawkish members of the U.S. Congress spoke of invading the northern provinces. Money markets crumbled. The American sectional crisis appeared to be at the threshold of becoming a world war.

Measuring the situation, Lincoln saw little hope. To give in to British demands would make him appear weak and malleable. To resist would invite a two-front war. In typical fashion, he chose a middle path. Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward quietly released Mason and Slidell, and Britain received a sum of money. Yet there would be no apology, as Wilkes had captured the men without orders. Congress angrily tolerated the decision, while Lincoln’s critics had a field day.77

When news of the compromise reached war-fearing London, the reaction was somewhat different. Church bells rang out, people cheered in the streets, and crowds sang to peace and the monarchy.78

There was no functioning transatlantic telegraph cable until 1866, a device many believed would have diffused hostilities over the Trent Affair in minutes rather than months.

6. France in Mexico (December 1861–May 1867)

Although the United States was not politically stable, its neighbor Mexico was faring even worse. A series of civil wars had left Mexico fragmented and indebted. On December 8, 1861, more than six thousand Spanish troops landed at the gulf city of Veracruz, followed soon after by smaller contingents from Britain and France. They seized the customhouse intent on recouping the millions owed their governments and citizens.79

Over time the Confederate and Union governments noticed something peculiar: The French were not leaving. On the contrary, a few hundred French soldiers became a few thousand, then tens of thousands. Napoleon III, emperor of France, had long harbored dreams of creating a foothold in Central America. With the United States distracted, he soon took control of half of Mexico.80

Instead of being praised for bringing order to the area, Napoleon was soon on the receiving end of open hostility. Mexican president Benito Juárez attempted to save the country by armed resistance. The Lincoln government also threatened military intervention after the conclusion of its own war. The Confederacy initially offered to assist the French in exchange for diplomatic recognition, but when the deal faltered, Paris envoy John Slidell warned of a combined Union and Confederate invasion force sweeping the French from the Western Hemisphere.81

Fearing reprisals both in Mexico and in Europe, the French began a gradual withdrawal in 1866. Their puppet emperor, Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, stayed behind, much to his misfortune. In May 1867 Juárez and his soldiers captured Maximilian, tried and convicted him, and executed him by firing squad.82

In May 1862, at the city of Puebla, the liberal Mexican government scored an unlikely victory against the French army. Although the one-day engagement did not drive the foreigners out, it did serve as a rallying point for future success. Mexico still celebrates that battle, fought on Cinco de Mayo.

7. The U.S.-Russian Alliance (1862–65)

Both Confederate and U.S. diplomats struggled to find allies during the war, but no major power appeared willing to choose sides. Then the Union found support from a most unlikely source.83

Lincoln had been a long-time critic of the Romanov dynasty. Before his presidency, when lamenting the anti-immigrant movement in the United States, he wrote, “I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure.”84

In 1862 Russia was still a Romanov dominion, but surprisingly Czar Alexander II pledged his unilateral support to the Lincoln administration. If France or Britain entered the war against the Union, vowed Alexander, Russia’s position would be made clear in a “decisive manner.”85

In the autumn of 1863 Alexander gave credence to his words when the Russian Imperial Navy staged simultaneous visits to the harbors of San Francisco and New York. The act was far from altruistic. During the Crimean War (1853–56), France and Britain had battled the czar’s fleet in the Baltic. Expecting another fight, Alexander sent his warships to America, simultaneously sparing his ships and flaunting a newfound partner.

Regardless of the motivation, the effect solidified Union prestige and morale. If Britain and France were not going to join the North, they were certainly less likely to oppose it hereafter. For seven months the Russian navy remained, and its thankful hosts treated the crews with overt hospitality. Few were more pleased with the imperial presence than U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, who wrote in his diary, “God bless the Russians.”86

Lincoln did not send his best men to St. Petersburg. His first ambassador was Kentucky abolitionist Cassius M. Clay, who became fond of street fighting with the Russian locals. Next was Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s inept and corrupt first secretary of war, who quit promptly after meeting the czar. Cameron’s replacement? Cassius Clay.

Russian ships visited New York and San Francisco in 1863 as a show of support for the Lincoln administration.

8. The Catholic Question (November 1863–January 1864)

By 1863 the contest had clearly become one of attrition, which did not bode well for the South. The Union outpopulated the Confederacy more than two to one. In terms of white males of military age, the ratio was almost four to one.

Immigration was the major reason for the disparity. Nearly 30 percent of the North was foreign born, compared to just 9 percent of the South. Despite the outbreak of war, the trend continued. Hundreds of thousands still sailed into the harbors of New York, Boston, and elsewhere each year, replenishing the North with fresh workers and soldiers.87

Then, in the summer of 1863, Pope Pius IX wrote his cardinals in New York and New Orleans and called for peace. The news came as a ray of hope for the Confederacy. The majority of the huddled masses coming into the Union were from Catholic regions of Europe—Belgium, France, southern Germany, Ireland, and Italy. Jefferson Davis immediately sent a diplomat to Rome.

Envoy Ambrose D. Mann reached the pope in November 1863. In his hand was a letter from Davis, describing the unspeakable slaughter of Catholics in the New World. The Confederate president implored the pontiff to discourage Catholics from coming to America, or at least to deter them from volunteering to fight. He added: “We have offered up at the footstool of our Father who is in Heaven prayers inspired by the same feelings which animate your Holiness.”88

The pope was visibly moved and offered to write a letter in response for the world to see. Mann was ecstatic. Rome had “all but recognized” the Confederacy.

The dream, however, ended with the pope’s response. Although addressed to the “Illustrious and Honorable Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America,” there was no mention of official recognition, no request to stop Catholic immigration, and no restriction on Catholics serving in the Union armed forces. The letter contained nothing except a repeated request to end the war.89

Over the course of the war there were more foreign-born Catholics in blue than there were Virginians in gray.

9. Canada and Confederate Raiders (January 1862– November 1864)

Of the possible escalations of the war, a border war between the North and British North America was the most likely. From the Revolutionary War to President James Polk’s threat of “54-40 or Fight,” the American-Canadian boundary had been an arena of international hostility.90

High-ranking Confederates were hoping to foment this hostility into open warfare. Others, including Jefferson Davis, wanted to respect Canadian neutrality and still use the provinces as a staging area for raids. To this end, Davis sent several well-funded operatives to Toronto and other points north.91

Rumors foretold of inevitable sabotage in Buffalo, a Confederate legion of five thousand men headed for Maine, an army of thirty thousand from Poland bound for Nova Scotia, but nothing happened. Some of the more substantive threats—such as a plot to rescue prisoners of war from Johnson Island in Lake Erie and an attempt to start riots in Chicago during the 1864 election—were real. Cracked codes and Canadian detectives, however, uncovered schemes before they could take form, at least until autumn 1864.92

On October 20 a party of twenty or so Confederate raiders left Montreal and sifted into St. Albans, Vermont. Once there, they robbed three banks of two hundred thousand dollars, stole horses, murdered a civilian, and attempted to set the town on fire. A posse chased them into Canada, and it looked as if the South would get its two-front war.

Nothing of the sort transpired. Canadian sympathy for the South faded fast, and the provinces clamped down on subversive behavior. Even the most anti-Union citizens of British North America did not want to support guerrilla warfare, especially at the risk of facing a Union army of a half million.93

Before the war there were at least twenty thousand Southerners living in Canada. Nearly all of them were former slaves.

10. The Kenner Expedition (March 1865)

In December 1864 Jefferson Davis sent Louisiana congressman Duncan F. Kenner on a secret diplomatic mission to Europe. Kenner was to offer the emancipation of Confederate slaves in exchange for recognition.

Kenner’s assignment illustrated the grave condition of the Confederacy. Davis knew that under his constitution, only the individual states could grant emancipation, not the executive branch. Making matters worse, Davis never consulted the states over the plan. It is unknown what he would have done had either London or Paris agreed to the offer.

As it turned out, Davis had no decision to make. With all Southern ports blockaded, Kenner had to travel north incognito and sail out of New York Harbor, losing valuable time. He did not reach Paris until March 1865. Once there, Kenner listened to a reluctant Napoleon III defer to Lord Palmerston. With the Confederacy on its last legs, Kenner rushed to London and the prime minister. After hearing the offer of quid pro quo, Palmerston offered a snide retort, suggesting the Confederacy never proved itself in control of its alleged borders. Palmerston’s cynicism became fact when Richmond fell two weeks later.94

Confederate congressman Duncan Kenner was one of the largest slave holders in the South, possessing more than four hundred persons at the start of the war.