Frequently granted the nebulous title “first modern war,” the War Between the States is also credited with birthing a multitude of maiden events. Most of these distinctions are misplaced, as the war enhanced far more than it created.

The Crimean War (1853–56) witnessed the first use of railroads and telegraphy in military operations as well as the pioneering of organized nursing. Photographers made a handful of exposures during the Mexican War (1846–48). Free blacks and slaves fought in the American Revolution (1775–83). The French employed dog tags in the early 1800s and balloon reconnaissance in the early 1700s. Rifles, grenades, land mines, and multibarreled “machine guns” had been around since the Middle Ages.1

Conversely, the Civil War was not the last of many things. Slavery remained for years in Cuba and Brazil and never ended in areas of Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In the 1950s all eleven states of the former Confederacy maintained laws of segregation. In the later decades of the twentieth century, citizens of Kansas, California, and Hawaii contemplated seceding from the Union.

Yet the war was still a vanguard event in a few cases. The following were the first of their kind in American or world history. They are ranked chronologically, although their impact upon the war and the world is left to the reader’s imagination.

1. First National Income Tax in American History (August 5, 1861)

It must have been a bitter pill for states’ rights advocates. The price of secession included the creation of a first-ever national income tax, both for the United States and the Confederacy.2

The first siphoning came from the U.S. government, enacted four months into the war. It was a dream by today’s standards. In order to increase revenue, Congress imposed a tax of 3 percent on all yearly income above eight hundred dollars, an amount well above the annual revenues for most farmers and laborers. In 1862 a new plan taxed cigarettes, liquor, stamps, inheritance, and a mountain of other items. It also expanded the income tax to 3 percent for earnings above six hundred dollars and 5 percent on the rare income above ten thousand dollars.3

Even less fond of taxation than Northerners, Confederates waited until 1862 to impose an income tax of 5 percent. By 1864 the levy was up to 10 percent. With much of its wealth in slaves and land, and a large portion of its population under occupation, the Confederacy had little to collect and no way to collect it. In the end the South financed most the war on the less invasive but highly speculative printing and borrowing of money.4

After the war, the U.S. government suspended the income tax for years but never closed the department created to enforce it. Ever since the Civil War, Americans have lived with the Internal Revenue Service.

2. First Paper Currency as Legal Tender (February 25, 1862)

By Christmas 1861 the U.S. government was nearly bankrupt. Creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of economic collapse, citizens hoarded gold and silver. Tax revenues were not due for months. Daily federal expenditures reached millions of dollars. Lincoln lamented, “The bottom is out of the tub.”5

To alleviate the immediate problem, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase demanded the issue of a paper currency. Paper money existed, from state and city banks, even shops and railroads. The system worked because most transactions were local, but Americans from all regions historically distrusted federal control over money. The U.S. Constitution permitted the minting of coins, but it mentioned nothing of paper. For the Federal government to print money was unconstitutional, or at least an abuse of power, some argued.6

Legal implications aside, lawmakers feared the public would reject a national scrip. As non-interest-bearing and unbacked by gold or silver, U.S. notes could become as worthless as the paper on which they were printed. Chase assured this money would be different.

Unlike existing paper money, or the notes the Confederate government, states, cities, and business were printing, the U.S. currency would be legal tender. With a few exceptions, citizens, businesses, and the government itself had to accept the money “for all debts public and private.” Practicality won over suspicion, and Congress passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862. The U.S. Treasury issued $150 million in notes.7

The Confederate money guaranteed nothing, except to be redeemable in silver two years after the successful conclusion of the war. In four years, the U.S. government issued $450 million in notes; which retained most of its value. The Confederacy printed $1.5 billion in notes, counterfeiters added millions more, all of which became little more than souvenirs with the fall of Richmond.8

Printed green on one side, U.S. national currency was nicknamed “greenbacks.” Printed with low-quality ink that faded after brief use, Confederate money was sometimes called “graybacks,” but the term was more often a pseudonym for lice.

3. First Battle Between Ironclads (March 9, 1862)

Neither the Monitor nor the Merrimack (rechristened the CSS Virginia) was the first iron-armored warship. France created the first seagoing ironclad in 1859, with Britain building two in 1860. Ironclad ships, however, had never faced one another in battle—until the Civil War.9

Intended to break the Union blockade, the CSS Virginia was almost as long as a football field and sported ten guns, four inches of armor, and a crew of 320. In her hull were five massive coal-burning boilers, capable of giving the “floating barn roof” a top speed of just a few knots. Launched from Norfolk, Virginia, on March 8, 1862, the slow ship quickly proved its mettle in action.

The lumbering ironclad headed for U.S.-held Hampton Roads, where three sailing ships and two steam frigates, all amply armed, blocked the mouth of the James River. Unimpressed, the Virginia rammed one ship, blasted another, and chased another aground. More than 240 U.S. sailors died that day. The Virginia took ninety-eight direct hits but experienced no damage.10

Word of the Virginia’s success sent Lincoln’s cabinet into a panic. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton feared the indomitable ship would sail up the Potomac and shell the White House. It would be prudent, Stanton insisted, to evacuate the cities on the eastern seaboard.11

That same night, a recently finished Union ironclad was towed into Hampton Roads and moored next to the grounded Federal warship. More than 170 feet long, the “cheese box on a raft” floated level with the water, except for a turret sheathed in eight inches of layered iron and holding two cannon. Faster and more maneuverable than the Virginia, the USS Monitor was just as sturdy.

Next morning the two warships hammered each other in a four-hour battle. Solid shots (each weighing more than a person) clanged against cast iron and deflected in all directions. Virginia ran aground, then freed herself. Monitor took a direct hit to its pilothouse. Each ship tried to ram the other.

Eventually the battle ended in a draw. As both sides scrambled to make more armored ships, the days of sails and masts were clearly numbered.12

The Confederacy spent $173,000 to build the Virginia. The Union spent $1.5 million just to review ironclad contractors and designs.

4. First National Military Draft in American History (April 16, 1862)

The year 1862 did not start well for the Confederacy. February defeats at FORTS HENRY AND DONELSON cost thirteen thousand men and exposed Tennessee to conquest. Failure at PEA RIDGE surrendered half of Arkansas. NEW ORLEANS, Kentucky, and northwest Virginia were all but back in the Union. New volunteers were few. ROBERT E. LEE, newly appointed military adviser to President Davis, recommended drastic measures.

In March Davis went before the Confederate Congress and proposed conscription for all able-bodied men between eighteen and forty-five. Those selected would serve three years or until the end of the war. One-year volunteers, most of them close to the end of their term, had to serve two additional years.

Legislators were furious. Not only did this violate the sanctity of states’ rights over the central government, it also illustrated the failure of Richmond to manage the resources, patriotism, and lives pledged to it since Fort Sumter. Reluctantly, two-thirds of the Congress voted for the Conscription Act, mandating eligibility of men not older than thirty-five. Exempted from the draft were skilled workers deemed invaluable, such as telegraphers, mail carriers, and train engineers, plus all Confederate and state government officials—the very men who enacted the draft law.13

Draftees were allowed to hire substitutes, but this sparked accusations of “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight.” The slogan’s intensity grew in the following draft, which exempted owners of twenty or more slaves.

The Union followed suit in March 1863. Sparking protests and riots, the draft netted only forty-six thousand of more than seven hundred thousand eligible. The rest paid a commutation fee of three hundred dollars, purchased substitutes, found exemption, or simply went into hiding. As with the Southern call-up, the Union draft coerced thousands to volunteer. The promise of bounties and choice of regiment was more appealing than being thrown into the mix and labeled a conscript.14

Among those in the Union who hired substitutes—future president Grover Cleveland, J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Lincoln’s personal secretary John Nicolay. Lincoln himself hired a substitute—John Summerfield Staple—for five hundred dollars.

5. First Production of Machine-Stitched Shoes (1862)

An enduring myth suggests that, out of necessity, the South was more inventive than the North. Creative though it was in finding alternatives, such as saving horsehair for sutures, sorghum for sugar, and dried acorns for coffee, the Confederacy never matched the Union’s eruption of innovation. In four years the Confederate Patent Office granted 266 patents, whereas its Union counterpart granted more than 16,000.15

By mail and in person, the White House and War Department received a blizzard of conceptuals, prototypes, and blueprints. Some wavered between comical and tragic, such as exploding bullets, steam-powered flying machines, weather-predicting equipment, and chemical and biological weapons. A handful of others could not be ignored, including a pair of shoes brought to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.16

There was nothing revolutionary about the footwear except for the way it was made. In 1858 inventor Lyman Blake patented a design for a specialized sewing machine. In 1862 Gordon McKay improved the design and began production with it. The machine stitched the soles of shoes to their uppers. Unexciting compared to the Gatling gun of the 1850s or the first use of chloroform in the 1840s, the invention was nonetheless a monumental achievement in that the process was previously done by hand.17

The McKay machine produced shoes cheaper, stronger, and one hundred times faster than before. Skilled shoemakers, in short supply during the war, were no longer required to fill huge army requisitions. Leased to subcontractors, McKay’s contraptions produced more than two million shoes in a year. All the while, thousands in the Confederate Army marched barefoot.18

In 1895 the United States produced 120 million pairs of shoes. More than half were made with McKay sewing machines.

6. First U.S. Medal of Honor (March 25, 1863)

Medals were not a standard part of the American military. Traditional thinking considered them undemocratic and unnecessary. Ideally, serving one’s country was to be rewarding enough. For Union soldiers, this service often meant months of morale-sapping tedium wintering in camp, patrolling occupied areas, and waiting in siege lines. Even less eventful was blockade duty. In guarding thirty-five hundred miles of coastline with hundreds of other ships, a crew could go for months without making contact with a bona fide blockade-runner.19

To bolster morale, Congress authorized the president in late 1861 to award Navy personnel a Medal of Honor in recognition of efficiency and gallantry in service. In the summer of 1862 the Army Medal of Honor was introduced (an air force version was added in 1956).

The first recipients were members of the April 1862 Andrews Raid (also known as the Great Locomotive Chase), a party of twenty-one Ohio soldiers led by Kentucky spy James J. Andrews. Stealing a train engine at Kennesaw, Georgia, north of Atlanta, the band hoped to sabotage tracks and bridges but were soon captured near the Tennessee border. Eight were eventually hanged, eight escaped, and six were exchanged. On March 25, 1863, Secretary of War Stanton awarded the medal to six of the survivors. Eventually, all received the medal save for the civilian Andrews, who was one of the eight who were hanged.20

In all, 2,625 soldiers and sailors received the medal during the war. A reexamination of all awards in 1917 resulted in more than 900 revocations, but no other war neared the number of recipients in the War Between the States. Next closest was the Second World War, with 433 decorations. Over time, conditions for its issue became increasingly stringent, and now most honorees receive the award posthumously.21

For the Confederacy, no equivalent existed. The most a soldier could receive was a promotion or a favorable review in an official report.22

The current navy Medal of Honor is almost identical to its original 1863 version, where the human figure of Discord cowers before Minerva (the Roman goddess of war), the two symbolizing the Confederacy and the Union respectively.

7. First Woman Surgeon in U.S. Military History (September 1863)

Before, during, and long after the war, a patriarchal American culture condemned the idea of women in the medical profession. Only a few medical schools accepted female students, and fewer communities allowed women doctors to practice.23

The military was no different. In 1861 medical practitioner and graduate of a Syracuse medical school Mary Edwards Walker applied for a surgeon’s commission in the Union army. Officials rejected her outright.24

Between hounding Washington officials for reconsideration, she volunteered as a nurse. She also provided assistance to families visiting loved ones in camp hospitals. Early in 1864 she finally received an appointment as an assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland, the first woman surgeon ever commissioned by the U.S. military.25

Evidence suggests her appointment may have been more for her capacities as a spy than as a doctor. In 1864, while crossing enemy lines to care for civilians, she was taken prisoner and convicted of espionage. The recipient of considerable ridicule, she served four months in a Richmond prison. Her jailers, however, acknowledged her commission and exchanged her, along with other Union surgeons, for seventeen Confederate medical personnel.26

In 1865 Mary Edwards Walker received the Medal of Honor. A review board repealed the decoration in 1917 because she was technically a civilian. In 1977 the award was reinstated, and Walker remains to date the only female recipient of the award.

8. First Time a Submarine Ever Sank an Enemy Ship (February 17, 1864)

Diving contraptions existed long before the Civil War. A fully encased one-man vessel of ingenious design tried to sink a British ship during the American Revolution by attaching a bomb to its hull. Robert Fulton experimented with below-water vessels before he began his work on steamships. Nevertheless, a submarine had never sunk a ship in wartime.27

In a fit of optimism, both Union and Confederate governments contracted for submarines. Launched in 1862, the four-man USS Alligator proved too unwieldy and never saw combat. The two-man CSS Pioneer was scuttled in New Orleans to avoid capture. The following CSS American Diver was lost while being towed out into Mobile Bay. Then there was the H. L. Hunley.28

Built in an Alabama machine shop and brought to South Carolina by rail, the Hunley was forty feet long and barely four feet wide. Engineers equipped it with two hefty hatches, tiny portals, ballast tanks, rudders, fins, and a faulty air shaft. Two of its test runs ended in disaster, drowning twelve men and its inventor in the process. Ultimately, the Hunley proved deadlier to its crew than to the enemy.29

On the night of February 17, 1864, a crew of eight crawled inside the converted boiler, an engineering wonder bobbing in the cold waters of Charleston Harbor. Huddled to one side, sitting in candlelight, the men began to operate the drive-shaft crank, and the pilot steered the submarine into the open water. From its bow projected a twenty-foot iron pole holding a ninety-pound keg of black powder, destined for the USS Housatonic out in the harbor of Charleston.

The crew of the Housatonic knew to be on watch. The Hunley and most other “secret weapons” were hardly unknown to either side. When a lookout spotted a suspicious rippling in the harbor waters, Union fears were confirmed.

Just as the alarm bells rang out, the Hunley’s spar torpedo detonated. Fire, water, wood, and bodies flew skyward. The Housatonic rolled to port. Sailors scrambled for the mast riggings as the ship sank in shallow water.30

Damaged in the attack and equipped with primitive navigation equipment, the Hunley wandered seaward and sank, drowning all 8 hands. Only 5 of Housatonic’s 155 perished, yet the Hunley had done something never before accomplished. Not until 1914 would a submarine sink another ship.31

After the war, circus mogul P. T. Barnum offered one hundred thousand dollars for the recovery of the Hunley, but no one was able to claim the prize. Not until 136 years after it went down was the famous sub found and salvaged.

9. First Assassination of an American President (April 14, 1865)

Lincoln knew full well that head of state was not a safe occupation. In his lifetime, assassins tried to kill Queen Victoria and Andrew Jackson, and succeeded in killing two czars, an emperor of Mexico, a prime minister of England, and a king of Afghanistan. In 1862 alone, assassins murdered the presidents of Colombia and Honduras. After the fall of Richmond, Jefferson Davis seemed to be the next likely target, as thousands North and South blamed the Confederate president for the war and its consequences.

It was April 14, Good Friday, just days after ROBERT E. LEE had capitulated at Appomattox. A similar surrender was expected in North Carolina, where WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN had JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON cornered. Washington, D.C., was in a festive mood.

News spread that Lincoln would be attending Ford’s Theatre that night to see Our American Cousin, a mediocre comedy. Exhausted but feeling obligated to make an appearance, Lincoln went.

Assigned to guard the presidential box were a White House footman and a policeman, the typical arrangement. Except for public speeches and on travels, Lincoln rarely had anyone guarding him. Perhaps more guards would have been present had Lincoln’s original guests accepted his invitation, but U. S. Grant and his wife had cordially declined.

As the play progressed, the policeman wandered from his post, and the footman thought nothing of allowing a famous stage actor to call on the president. Moments later, the actor blasted a .44 caliber bullet through the president’s occipital lobe.

Lincoln lived nine more hours, unconscious. Carried to a boarding house across the street, he slowly hemorrhaged to death in front of his cabinet, doctors, and his wife. At 7:22 a.m., April 15, 1865, his heart stopped.32

Since then, attackers have launched at least eight direct assaults upon the lives of U.S. chief executives. These attacks proved fatal to Civil War veterans James A. Garfield (1881) and William McKinley (1901), and to World War II veteran John F. Kennedy (1963).

Lincoln had long frequented the playhouses of the capital. On one visit to Ford’s Theatre, he partook of a play titled The Marble Heart, starring John Wilkes Booth.

A single bullet reaped horrible consequences for the South after the war.

10. First Woman Executed by the U.S. Government (July 17, 1865)

Conspiracy theories erupted after the slaying of Lincoln. The implicated included the papacy, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and the Confederate army. In flight from recently captured Richmond, Jefferson Davis was also a prime suspect. Yet there was no doubt about the hit man.

Several witnesses recognized the assassin immediately as he leapt from the president’s box. A star of Ford’s and many other theaters, John Wilkes Booth made no attempt to hide his face as he limped across the stage, brandished a dagger, and shouted, “Sic semper tyranis” (“Thus ever to tyrants,” the state motto of Virginia).

The murder investigation quickly led to Mary Surratt’s Washington boarding house, where Booth was a frequent visitor. After a few questions, police arrested the forty-two-year-old Surratt when she denied knowing Lewis Powell, alias Lewis Paine, a man who attempted to kill Secretary of State William Seward on the night of the assassination. Paine, along with several other members of Booth’s inner circle, was one of Surratt’s boarders.33

Surratt and seven men were tried in a military court. Evidence against her was speculative. Her son John was familiar with Booth. An associate of hers, John Lloyd, testified Mary spoke to him on the day of the shooting about acquiring some firearms. Otherwise, there was nothing to link her with the conspirators. A national desire for revenge, however, prompted the conviction of all eight defendants. Four were to be hanged, including Surratt.

Two days after sentencing, on a hot summer afternoon, Surratt, Powell, George Atzerodt (assigned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson), and David Herold (who helped Booth escape from Washington) entered the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison. Led to the gallows, their legs were bound. Hoods were placed over their heads. Powell begged for Surratt’s life, proclaiming her innocent. Just before the stroke of 2 p.m., the platform upon which they were standing swung away. Officials let them hang for half an hour.34

John H. Surratt, Mary’s son, fled the country and spent time in Rome. Nearly captured, he fled to Alexandria, Egypt, where he was eventually apprehended. Brought to trial in 1867, he was released for lack of evidence.

Images of charging horses, bursting cannon, and waving flags tend to inspire the imagination more easily than scenarios of financial balance sheets and cleverly worded legislation, but there is much discrepancy among historians as to the importance of battles in history. Traditionalists might condone the “Great Man Theory,” in which generals and presidents are the primary directors of fate, whereas social and economic historians often interpret battles as expressions rather than instigators of existing conditions.

Whatever the view, it is important to consider that in the case of the Civil War, large portions of the opposing sides opted for warfare to settle their differences. In turn, battles within the war played a noticeable role in determining political options, economic climate, and national morale. One Confederate soldier offered a poignant view of battles and their role: “If we don’t get at each other sometime, when will the war end?”35

Militarily speaking, cavalier strikes and spur-of-the-moment miracles did not decide the war as much as long, decimating campaigns. Within those campaigns, there were battles of considerable effect, some of which are represented below. Listed here, in chronological order, are the military engagements marking the greatest change in the nature of the war in terms of military, economic, and political consequences.

1. First Manassas (Virginia, July 21, 1861)

A close fight between green troops, First Manassas (First Bull Run) ended with a timely counterattack from the Confederates, who worked from the defensive for most of the action. Considering their inexperience, Union soldiers attacked much better than they withdrew. Rumor and roadblocks turned an otherwise orderly disengagement into a full-fledged panic, sending Confederate morale skyward.36

The popular view is to consider First Manassas a costly win for the South. Overconfidence from the victory, so the theory goes, actually lulled the Virginia theater, and the Confederacy as a whole, into a fatal complacency, while the North mobilized for a long fight. This is an odd interpretation in light of the results.

The Union did not launch another offensive toward Richmond for the rest of 1861 and several months into 1862. If the Washington area prepared for war, so did Virginia. Safe from harassment, the Confederacy’s most populous and industrialized state organized defenses and gathered munitions. The “overconfidence” of Manassas would serve the Virginia theater well, acting as the base for future victories at the SEVEN DAYS’ BATTLES (June–July 1862), SECOND MANASSAS (August 1862), the Shenandoah Valley (March–September 1862), FREDERICKSBURG (December 1862) and CHANCELLORSVILLE (May 1863).

A late arrival to the battle, one of the many famous onlookers to First Manassas was Confederate president Jefferson Davis, who briefly considered leading a group of stragglers into combat.

2. Forts Henry and Donelson (Tennessee, February 6, February 12–16, 1862)

It is easy to dismiss rivers when looking at a map. The twenty-first-century traveler rarely thinks of waterways, as they are made almost irrelevant by concrete roads and steel bridges. To a military tactician in the nineteenth century, however, the cartographer’s blue lines were formidable obstacles and potential death traps. Rivers were also highways on which an army could move deep into its opponent’s territory.

There are only three major rivers leading from the North into what was the Confederacy: the Mississippi, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee. Stemming from the Ohio River, the latter two enter northwest Tennessee a dozen miles apart. Guarding the Tennessee was Fort Henry, and holding the Cumberland was Fort Donelson.

In ten days, ULYSSES S. GRANT led a combined land and water assault upon the forts and delivered the Union its greatest victories of the war to that point. Of the two battles, Fort Donelson is by far the more famous. Maintained today as a national battlefield park, it was the larger and latter of the two contests and the site of a costly Confederate blunder. Winning the Cumberland provided a water route along the Kentucky-Tennessee border, which the Union used to take the vital rail link of Nashville.

Arguably, the Union triumph at Fort Henry was more significant. The Tennessee River cuts through the western third of its namesake, skirts the northwest corner of Mississippi, runs across north Alabama, approaches Georgia, then reenters the southeast edge of Tennessee. The Union used this river run to secure major victories at SHILOH (April 1862), Iuka (September 1862), Corinth (October 1862), and CHATTANOOGA (November 1863).

Refusing terms of capitulation to his captives at Fort Donelson, U. S. Grant received the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

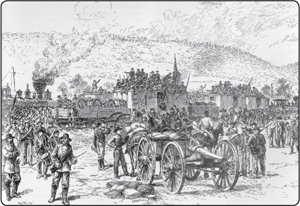

Union victories at Forts Henry and Donelson were the first good news for the North and signaled the presence of Ulysses S. Grant.

3. New Orleans (Louisiana, April 23–25, 1862)

It was by far the largest city in the South, holding more people in 1861 than Atlanta, Charleston, Montgomery, Nashville, and Richmond put together. The linchpin between the Father of Waters and the Seven Seas, New Orleans trafficked more commerce than all other Southern ports combined. The Confederacy could not give it up, let alone give it away.37

Yet several factors doomed the Crescent City. In early 1862 a Union advance toward the railroad hub of Corinth, Mississippi, forced Confederate troops out of Louisiana and into the bloodbath of SHILOH. Left holding New Orleans proper were three thousand militia, supported downriver by several small ships, one functioning ironclad, and two masonry forts—all of which was little challenge to a Union fleet of forty-three gunboats and a land force of fifteen thousand. On April 24, 1862, after shelling the two river bastions into rubble, Union Rear Adm. David G. Farragut ran his ships upriver and captured New Orleans the next day, with Gen. BENJAMIN F. BUTLER’S army close behind.

The fall of New Orleans was a crushing blow to the South, the rough equivalent to the Union losing New York City. The fact that New Orleans fell after minimal fighting made the news particularly bitter to loyal Confederates.38

In short order, the Union captured a metropolis of 180,000, gained inroads to the Confederate interior, seized the lower part of the Mississippi, and added a premium port to its blockade operations. For all of this, the Union lost 36 men killed and 135 wounded.39

The Union hero of New Orleans, Rear Adm. David Glasgow Farragut, was born in Tennessee and married a Virginian. His mother, who died when he was a child, was interred in New Orleans.

4. The Seven Days’ Battles (Virginia, June 25– July 1, 1862)

Despite the overwhelming caution of Union commander GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN during his Peninsula campaign, the Army of the Potomac had drawn within sight of the Confederate capital. HARPER’S WEEKLY predicted Richmond would fall in days if not hours. The combined armies numbered a fifth of a million men, but the Union held a two-to-one advantage.

Replacing a recently wounded JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON at the head the Confederate defenses, the heretofore unimpressive ROBERT E. LEE chose to attack. In six different battles within a week, Lee drove the Union forces back. Performing far better than their cautious leader, the Federals won most of the battles and induced twice as many casualties as they received. Consequently, many in blue were shocked to hear the command to retreat day after day.40

Overall, the Seven Days was wrought with paradox. Clearly it was a Union defeat. McClellan abandoned the offensive, plus tons of equipment—including thirty-one thousand rifles—citing he was facing overwhelming numbers. Yet Lee viewed the campaign as a defeat as well, because he hoped to bag the entire Union force. The Union won four of six battles outright, yet retreated six times. The Confederates drove the Federals back nearly thirty miles and away from Richmond, yet suffered twice as many deaths.

However, three great changes occurred. McClellan, once the darling of the Union cause, plummeted in stature. Many Northerners were so incensed by his pathetic performance that they wanted him charged with treason. In contrast, the campaign signaled the grand ascension of Lee, who beforehand had been relegated to managing coastal defenses after failing to hold northwest Virginia in 1861. For Lee’s defense of Richmond, his fellow Confederates elevated him to mythical greatness. Lastly, the campaign was one of the war’s most lethal. Altogether, more than twenty-eight thousand men were killed or wounded. Taken collectively, the Seven Days’ battles cost more lives than any other battle with the exception of GETTYSBURG.41

To hasten his army’s retreat after the Seven Days, Union commander George B. McClellan contemplated leaving all of its supplies, weapons, and ammunition behind.

5. Antietam (Maryland, September 17, 1862)

After hearing of ROBERT E. LEE’S impressive victory at SECOND MANASSAS, British foreign secretary John Russell wrote to Prime Minister Lord Palmerston: “The time is come for offering mediation to the United States Government, with a view to the recognition of the independence of the Confederates.” The date on the letter was September 17, 1862.42

Ten days later news reached London of another battle “to the northwest of Washington,” which had transpired the same day Russell had suggested a radical change in British policy. Details of the battle were not yet clear, but evidently the Union had prevailed, and Lee was falling back.

Militarily, the triumph was marginal. The Union victory near Sharpsburg broke a string of Confederate victories in the region. Loyal Northern newspapers initially called Antietam a smashing success, until they discovered that it cost of twelve thousand Union dead and wounded. The “victory,” however, allowed Lincoln to announce his pivotal EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, bringing a new sense of purpose to his country and to the war.43

For the Confederates, the defeat was initially a terrible shock. Lee would not attempt another sortie for ten months. Jefferson Davis fell into despair, as did many citizens and soldiers of his country who assumed Lee’s successes would continue unabated. In eleven hours the South lost more than eleven thousand killed and wounded, a number larger than many Confederate cities. Though many did not yet realize it, defeat at Antietam also meant the end of British plans to intervene.44

At the time of the battle, there were around thirteen hundred residents of Sharpsburg, Maryland. After the battle, dead soldiers in the immediate area outnumbered them four to one.

The stalemate at Antietam allowed Lincoln to publish the Emancipation Proclamation. It also ended the command of George B. McClellan.

6. Chancellorsville (Virginia, May 1–4, 1863)

When hearing of the Union defeat near Chancellorsville, a Northern newspaper editor could hardly believe the news. “My God! It is horrible—horrible, and think of it, 130,000 magnificent soldiers so cut to pieces by less than 60,000.” Chancellorsville was one of the most unexpected, almost unimaginable achievements of the Confederate military.45

Facing a vastly larger army and about to be outflanked, Lee ignored nearly every military axiom and divided his forces three ways. With his left, he outflanked the flankers, then crushed them between his left and his center. When his right came under attack, he gathered his divided army and defeated that advance as well.

Much of the victory was due to the blundering hesitation of Union general Joseph Hooker and the brilliant leadership of the Confederate corps commanders, particularly THOMAS J. “STONEWALL” JACKSON. Regardless, Lee’s image was the chief beneficiary, as the stoic Virginian looked as unstoppable as ever. Summing up the emotions of many fellow Unionists, Republican Sen. Charles Sumner cried, “Lost, all is lost.”46

Yet the victory cost the life of Jackson and killed or maimed 22 percent of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Rather than GETTYSBURG, many now see Chancellorsville as the high tide of the Confederacy, soon to ebb from the overconfidence Lee displayed in Pennsylvania two months later.47

During the battle of Chancellorsville, at least one Union soldier was the victim of corrupt government contractors. He discovered his rifle cartridges were filled with dirt rather than gunpowder.

7. Gettysburg (Pennsylvania, July 1–3, 1863)

An abrupt fight with legendary tales of heroism, the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere, Gettysburg captures the imagination unlike any other Civil War battle, especially when compared to the slow, extenuated grinds of the blockade, the siege of Vicksburg, or the siege of Petersburg.

Because of its size, northern location, and dramatic turns of battle, Gettysburg also invites a deluge of what-if scenarios or counterfactual history. Against countless variables, any hypotheses on different outcomes and effects are basically guesswork.48

What the battle did provide was a major surge in Union morale. Many soldiers in the Army of the Potomac felt as if the recent defeats at FREDERICKSBURG and CHANCELLORSVILLE were avenged. The army expelled Lee from the North as it had done at ANTIETAM.

Yet the Union president was less than pleased. George Gordon Meade failed to pursue his beaten opponent, allowing the Confederates to cross back into Virginia unopposed. “This is a dreadful reminiscence of McClellan,” vented Lincoln, fuming over what he viewed as a lost chance to capture the Army of Northern Virginia in total. In a scathing rebuke to Meade, he wrote: “Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.” To admonish a victorious general, however, would be to undermine the victory itself. Lincoln never sent the message.49

On the Confederate side, sympathetic journalists referred to Gettysburg as a “brief setback” if not a victory. It was in fact the deadliest battle of the war for the South. Nearly a third of the Confederacy’s largest army was gone. Desertions accelerated rapidly. Lee remained on the defensive for the rest of 1863 and never invaded the North again. Yet the loss was not total. His army would live to fight another day—another 645 days, to be precise.50

Victor of the largest battle ever fought in the United States, Union commander George Gordon Meade had been born in Spain.

Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg proved unsuccessful in routing the Union army. As a result, Lee retreated to Virginia and never again came north. In terms of the battle itself, many have emphasized it was lost by Lee rather than won by Meade.

8. The Surrender of Vicksburg (Mississippi, July 4, 1863)

On the afternoon of July 7, while working through his frustration over the limited victory at GETTYSBURG, Lincoln received a visit from a visibly ecstatic Gideon Welles. With telegram in hand, the navy secretary informed the president that Vicksburg had fallen to U. S. Grant and W. T. Sherman. Embracing the messenger and the good news, Lincoln beamed, “I cannot in words tell you of my joy over this result! It is great, Mr. Welles! It is great!”51

For months, the Union army had tried charging, digging, flanking, and shelling its way into the Mississippi town. After Grant’s army surrounded the city and laid siege for forty-seven days, the Confederate stronghold capitulated on the Fourth of July. As specifics came in, Lincoln had even more reason to celebrate. Grant had taken 31,600 prisoners and more than 170 cannon, six times Meade’s catch at GETTYSBURG. Nearby Port Hudson fell soon after, contributing 5,000 more prisoners and giving the Union control over the length of the Mississippi.52

Paris and London heard the results of GETTYSBURG a few days before learning of Vicksburg, but it was the news of the latter that sent Confederate credit on a dive. Domestically, inflation in the South accelerated, as did its military desertions.

Losing the mighty river, the Confederacy also lost connection to Arkansas, much of Louisiana, and Texas, which held more cattle and horses than any other state. For the Union, the dollar surged in strength, and the growing Midwest could once again trade with the world. The end of the Vicksburg campaign also freed up men and materiel for operations eastward, namely in Virginia and Georgia, where Grant and Sherman would launch their final grand offensives of the war.53

The Confederate commander at Vicksburg was John Clifford Pemberton, a native of Pennsylvania.

The fall of Vicksburg gave the Union complete control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in half.

9. The Wilderness (Virginia, May 5–6, 1864)

The names of Grant and Lee are frequently mentioned in the same breath, but the two generals faced each other for less than a quarter of the war. Their reintroduction (they had met briefly during the Mexican War) occurred in the thickets south of the Rappahannock River, in an area aptly named the Wilderness. The fighting was near Chancellorsville, where Lee had achieved his greatest victory a year earlier.

For two days, in close and brutal fighting, 101,000 Federals and 61,000 Confederates slashed into each other. Lee had once again stemmed a Union advance, registering over 14,000 killed and wounded while losing 7,750 of his own.54

The Union had lost in Virginia again, but rather than retreat northward and recover, Grant moved south, determined to continue the engagement until he outflanked or broke through the Confederate line. The Wilderness is most significant because it signaled the beginning of almost continual engagement that would finally terminate the stalemate in the East.

Although Grant’s plan would take eleven months to work, the immediate effect of the advance upon his troops was remarkable. Suffering yet another loss under yet another general, and losing more than twice the casualties as their opponent, the Federals were nonetheless heartened to be moving forward. One Union soldier commented, “We began to sing…We were happy.” 55

In the battle of the Wilderness, Confederate Gen. James Longstreet was wounded by gunfire from his own troops. Stonewall Jackson had been wounded by his own troops at Chancellorsville, a little over a year before and a little over a mile away.

10. Jonesboro (Georgia, August 25–September 1, 1864)

In August 1864 time was running out for the Lincoln government. Grant’s once aggressive Wilderness campaign had stalled on the outskirts of Petersburg, and all he had to show for his efforts were fifty thousand casualties. In August, Lincoln warned his cabinet by way of memorandum: “It seems exceedingly probable that this administration will not be re-elected.” Days later, the Democratic Party gathered for its national convention in Chicago, and declared the war a failure, a message heartily received by a growing peace movement in the North.56

WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN and his three armies offered no encouragement. Since May they had marched toward Atlanta from Chattanooga. On the way they lost twenty-five thousand casualties, including the life of promising Gen. James B. McPherson at the head of the Army of the Tennessee. Although under siege, Atlanta perservered.57

Then on August 25 Sherman instructed his forces to leave their trenches to the west of the city and head south. Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood declared victory, believing Sherman was retreating. Sherman instead headed to Jonesboro to cut the rail lines supplying Atlanta. After several days of denial, Hood eventually realized he was about to be trapped. In response, he set fire to his supply depots, and retreated. On September 1 Union forces moved into the city unopposed.58

At the time Atlanta was known as the “Gate City.” It lived up to its nickname for the Union. Its surrender opened the way for Sherman’s March to the Sea and a swath of devastation through Georgia and the Carolinas. More important, the fall of Atlanta was a clear indication that the war would soon end in favor of the Union. In the November elections, voters concurred. Lincoln, who was surprised to have been re-nominated by party back in June, retained the presidency by a wide margin.59

Real estate development has all but eradicated the battlefield of Jonesboro.

Schools, streets, and newborns continue to be named after beloved commanders of the Brothers’ War. Conversely, some generals are still vilified. Ranking the 1,008 generals of the Civil War depends on one’s criteria. For soldier morale, JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON may stand highest. In ferocity, few can top Nathan Bedford Forrest. GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN is among the very finest in terms of supply and organization.

The following are the best commanding generals based on their respective success in managing the primary variables of military operations, including tactics, logistics, communications, and overall strategy. Most important, they are measured for the magnitude of their contribution to the success of their side.60

1. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson (C.S., Virginia, 1824–63)

He was never wasteful with his soldiers yet pushed them farther and faster than any other commander. He won on the offensive and defensive, led forces small and large with equal precision, and used terrain and timing to defeat his opponents. With limited means, he played a major role in nearly every Confederate victory in the eastern theater. Perhaps his early departure spared him from eventual defamation, but while alive, Thomas J. Jackson had no equal on either side.

Eccentric, superstitious, and overtly pious, Jackson differed little from many other Americans of the period, but in the military, he was a complete misfit. He was aloof, humorless, awkward, and was often the target of ridicule from his unimpressed pupils at the Virginia Military Institute. Then the war started.61

To his troops he was best known as “Old Jack” or “Old Blue Light,” the latter nickname coming from the way his sky blue eyes glared in the midst of battle. He earned the title “Stonewall” while standing his ground against harsh opposition at FIRST MANASSAS. Yet it was his 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign that catapulted him into legend. From March to June 1862, with forces ranging from four thousand to seventeen thousand, far from rail and reserve support, vastly outnumbered, Jackson accomplished a military feat that remains a subject of international study. In three months he drove off three armies and held a fourth to the outskirts of Washington. His men captured thousands of men and millions of dollars in weapons and supplies, marched and countermarched hundreds of miles, and secured the upper Confederacy’s primary source of grain and cattle for the remainder of the year.62

A harsh disciplinarian, but not without purpose, Jackson was quick to punish and even execute the disobedient. The rest he pushed to the limit. Before the battle of SECOND MANASSAS, Jackson marched an entire corps of twenty-four thousand to a Federal depot at Manassas Junction, consumed or destroyed the entire cache and disappeared, covering fifty miles in two days. Figuratively and literally, Jackson created a lean fighting force, a “foot cavalry” unburdened by excess baggage, spoils, or the sickly. Few of his soldiers were fond of their taskmaster, but they were proud of the wins they habitually achieved.63

ROBERT E. LEE prized Jackson, for it was Stonewall’s men who held the field at Second Manassas, allowing Lee to move up reinforcements and win the day. In September 1862 outside Sharpsburg, Maryland, a vastly outnumbered Lee found his back to the Potomac and sixty thousand bluecoats advancing on his position. To Lee’s assistance came Jackson, marching up from his recent conquest of Harpers Ferry with two divisions, arguably sparing the great general from annihilation along the banks of the ANTIETAM. While Lee jabbed at Joseph Hooker outside CHANCELLORSVILLE, Jackson delivered a crushing left hook, marching twenty-four thousand men undetected past the Army of the Potomac then slamming into its right flank. It was a pivotal achievement and his last.

Riding reconnaissance that night, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men. Languishing on his deathbed, he received a letter from the grateful Lee: “I should have chosen for the good of the country to be disabled in your stead.”64

Early in the war, Thomas J. Jackson thought one of his officers would do well leading mounted troops, so he reassigned Jeb Stuart from the infantry to the cavalry.

2. William Tecumseh Sherman (U.S., Ohio, 1820–91)

He had lived in the South for a dozen years, owned slave servants, and detested the rise of agitating abolitionists. As a result, William Tecumseh Sherman understood the Confederacy better than most any other general in blue.65

Approachable, unceremonious, intense, and highly intelligent, Sherman led his brigade ably at FIRST MANASSAS, one of the few Union officers to do so. Yet he fell into a depression soon after, frustrated by the escalation of the war and the carnage that he was certain would come.

Transferred unwillingly to Kentucky, Sherman told the War Department it would take at least two hundred thousand troops to launch an offensive from the Bluegrass State. Word of his request leaked out, and several newspapers judged him insane. Sherman’s estimations for success were not far off, but he was acting paranoid, claiming that much of Kentucky’s civilian population were Confederate spies.66

Subsequently transferred, Sherman regained himself and his reputation after a solid performance as a division commander at SHILOH, receiving accolades from his immediate superior, ULYSSES S. GRANT. Thereafter, the two men were fast and loyal allies.

In many ways, Sherman was the antithesis of Grant. Better with organization and supply, excitable, racist, and frequently inflexible, Sherman was also a superior strategist. Grant smashed into armies; Sherman outmaneuvered them (with the exception of Kennesaw Mountain, where he lost 2,000 to the Confederates’ 270). Although he lost several battles, he knew how to win campaigns. In 1863 he helped secure the Federal rear at VICKSBURG, assisted in lifting the Confederate siege of Union troops at CHATTANOOGA, and repeated the feat immediately at Knoxville. The next year, Sherman conquered Atlanta, largely by maneuver.67

The campaign for which he is most famous (and infamous) is his late 1864 March to the Sea. Often criticized as a harbinger of “total war” that included civilians, Sherman’s strategy differed little from ROBERT E. LEE’S 1863 campaign into Pennsylvania. Lee intended to take Harrisburg, and fortune willing, the city of Philadelphia; an original version of a march to the sea. Sherman succeeded where Lee failed. And in destroying property, Sherman broke the will of the opposition without forcing the body counts of a COLD HARBOR, a CHANCELLORSVILLE, or for that matter, a GETTYSBURG.68

Before the war, Sherman was superintendent of a school that later became Louisiana State University.

3. Robert E. Lee (C.S., Virginia, 1807–70)

Feverish admirers hail ROBERT E. LEE as the patron saint of the Lost Cause, a knightly figure who rallied mortal disciples against heartless modernism. Critics accurately note that he lost a third of his men and half of his battles. Regardless of one’s position, there are general truths that endure scrutiny. Lee’s premier weapons were his corps commanders, an unsurpassed ability to anticipate his opponents’ actions, and a willingness to depart from traditional tactics. His unflinching commitment, exemplary conduct, and personal bravery in the line of fire inspired his men, his people, and his president. With inferior materiel, scant food, and dwindling ranks, “Marse Robert” repeatedly fought off the largest and best-equipped army on earth.69

It is safe to say he was not afraid to use his soldiers. To push back the Federal army from the gates of Richmond in 1862, Lee used up fifty thousand men in four months. For his brilliant 1863 win at CHANCELLORSVILLE, he lost thirteen thousand in three days. The 1864 WILDERNESS campaign halted yet another Federal invasion but cost Lee sixty thousand casualties. He was effective but expensive.

The best and the worst that can be said of Lee is that he fought for Virginia first and last. While his departure from the U.S. armed forces after a quarter-century of service is well known, many observers fail to appreciate something less obvious but just as authentic. Lee was not particularly loyal to the Confederacy either.

In 1862 Lee bolstered Richmond’s defenses with troops he removed from South Carolina and Georgia. When Jefferson Davis asked him to send reinforcements to besieged Vicksburg in 1863, he instead launched an offensive into Pennsylvania to relieve pressure on Virginia. His president once asked him where the next line of defense should be if Richmond were lost. He responded that there would be no other line.70

Yet in his fixation, Lee indirectly provided the Confederacy a great service. In protecting his home, he also protected the Confederacy’s most populous state (for both slave and free populations), its largest source of capital wealth and weapons, and a major source of its draft animals and grain. His presence forced the Union to commit a disproportionate amount of men and supplies for the protection of Washington, resources that otherwise would have been free to move upon other states. In defrocking one-time heroes like McClellan and “Fighting Joe” Hooker, outwitting John Pope and AMBROSE E. BURNSIDE, and keeping George G. Meade and U. S. GRANT at bay for nearly two years, the devout Virginian gave the South more hope and the North more despair than any other figure in the war.71

Lee’s record in major engagements: eleven wins, twelve losses.

4. Ulysses S. Grant (U.S., Ohio, 1822–85)

He was not particularly intelligent or inventive. Costly frontal assaults at VICKSBURG, THE WILDERNESS, and COLD HARBOR demonstrated an inability to learn from previous failures. He let his men die on the field or in prisons before negotiating with the enemy. Yet this unassuming man from Galena, Illinois, proved to be the only Federal commander willing to use the strongest weapon available to the Union: attrition. Arguably, he was also the only general on either side to orchestrate a truly unified war effort.72

Defeat itself did not stop him. It stopped his fellow commanders often enough: John C. Frémont, Don Carlos Buell, Franz Sigel, and Nathaniel Banks in the West, Irvin McDowell, George B. McClellan, John Pope, AMBROSE E. BURNSIDE, Joseph Hooker, and George G. Meade in the East. Through perseverance, Grant eventually triumphed in both theaters.

His unique trait of calm focus in the face of destruction was apparent in the Tennessee battles of FORT DONELSON and SHILOH. Both times, the Confederates opened offensives upon his lines. Both times, his men were not prepared. Both times, Grant himself was miles away, anticipating no imminent action. Yet both times he rode to the front and personally rallied his beaten troops, using a composed, calculating demeanor to reassure and reassess, turning defeats into hard-fought victories.73

His two great prizes, Vicksburg and Richmond, exemplified his effective use of abrasion. At first there were the preliminary rounds of reconnaissance and maneuver, followed by an exchange of fierce blows with tremendous loss of blood and no conclusive results. Rather than accept defeat in either affair, Grant resorted to strangulation by siege, letting time and superior numbers work in his favor.

After his appointment to general in chief of the Union armies in March 1864, Grant again accomplished something his predecessors and adversaries could not. He coordinated simultaneous assaults upon multiple theaters, eliminating the opposition’s ability to concentrate its defenses. Grand attacks began in Louisiana, the Virginia coast, the Shenandoah Valley, northern Virginia, and Georgia. The latter three would propel Philip H. Sheridan, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Grant himself into international fame and wither the South into capitulation in a little over a year.

When Grant lost, he usually lost to ROBERT E. LEE, to whom he could credit nine of his eleven major combat defeats.

5. James Longstreet (C.S., South Carolina, 1821–1904)

Fighting from FIRST MANASSAS to Appomattox, commander of the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, careful, stalwart, dependable Longstreet innately comprehended the precious limit of Southern numbers perhaps better than any Confederate general. His tool of choice was the counterattack, launching assaults only after weakening an opponent from the protection of a defensive stand.74

Blue-eyed, fair-skinned “Old Pete” was a man of clear kindness and few words. Good to his troops, his impressive height and sturdy build added to his image of a stolid and steady officer, an image that lasted through twenty-four years of military service: twenty for the United States and four with the Confederacy. A veteran of the SEVEN DAYS, ANTIETAM, GETTYSBURG, and THE WILDERNESS, Longstreet’s finest hours included his near-perfect infantry and artillery stand at MARYE’S HEIGHTS, his devastating counterattack against John Pope’s massive army at Second Manassas, and his assault through the Federal lines at CHICKAMAUGA.75

Lee frequently consulted him for advice, gave him premier assignments in several battles, and referred to him endearingly as “my old war horse.” Longstreet routinely performed orders with cohesive operation yet remained flexible and opportunistic once battles were in motion. Although not tremendously successful in independent command, Longstreet at the head of a corps proved to be the equal of Jackson.76

Longstreet’s granite reputation eventually crumbled, although it happened after the war. In the late 1860s he joined the Republican Party and spoke of conciliation with the victors. Consequently, several prominent Confederate colleagues reassessed his war record and openly questioned his loyalty as a Southerner. They recalled his failed 1864 siege of Knoxville, Tennessee, where he sent hundreds of men to their deaths in the deep moats of Fort Sanders, and they pointed to his apparent lethargy with troop deployment on GETTYSBURG’S second and third days.77

In response, Longstreet suggested the fault belonged to others, including his recently deceased mentor, ROBERT E. LEE. For this, Longstreet effectively erased his successes from Confederate lore.78

In 1848 Longstreet (fourth cousin to the bride) was best man at the wedding of Julia Dent and Ulysses S. Grant.

6. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart (C.S., Virginia, 1833–64)

Critics and admirers alike label him cavalier, immature, cocky, reckless. Many dilute his achievements as acts of foolish youth, made possible by blind luck and an initially inferior enemy. Jeb Stuart indeed pushed luck and limits, but his methods were far from haphazard. He worked tirelessly to create and maintain an orderly and industrious staff, removed officers he deemed ineffective, was skilled in governing artillery, infantry, as well as cavalry, and led forces from two hundred to twenty thousand to victory.79

Perhaps Stuart’s greatest contributions happened before the great battles: gathering priceless information at minimal cost. Before attacking McClellan during the 1862 Peninsula campaign, Lee asked Stuart to run reconnaissance. To oblige, Stuart and his troops rode completely around McClellan’s army, destroyed supplies, and captured soldiers. More important, he revealed just how cautious and stagnant the Army of the Potomac had become. The cost of this productive romp? Stuart lost only one of his one thousand men.80

The man called “Beauty” provided an encore before the battle of SECOND MANASSAS. Riding behind enemy lines, Stuart and fifteen hundred men destroyed supply wagons and took three hundred prisoners. They even captured Union commander John Pope’s dress coat, personal baggage, and tens of thousands of dollars in gold and greenbacks. The greatest prize was Pope’s own dispatch ledger, containing information on the Union army’s strength and disposition.81

After ANTIETAM, Stuart again circled McClellan and one hundred thousand soldiers. Stuart’s party of eighteen hundred left McClellan stunned, albeit thirty hostages and twelve hundred horses lighter. Just two of Stuart’s troops were missing after a raid of 125 miles.82

Hailed as a cavalry genius, the former infantry officer accomplished some of his most valuable work as a director of artillery and footmen. At FREDERICKSBURG, a Federal attack swept forward against THOMAS J. “STONEWALL” JACKSON and the Confederate right flank. Stuart repulsed the advance by unleashing his horse artillery upon the Union’s left flank. At CHANCELLORSVILLE, Stuart took over the Second Corps of the wounded Jackson, using infantry and artillery to force Hooker into full retreat.83

There are two incidents where Stuart is heavily (and to a degree justly) criticized. In June 1863 near Brandy Station, Virginia, Stuart staged a mock cavalry battle for admiring citizenry. Days later a real battle fell upon him. More than ten thousand mounted bluecoats swarmed down upon Stuart’s position. After attacks and counterattacks, with blasting pistols and swinging sabers, the Confederates held the field. Stuart declared it a great victory, where in reality he allowed the enemy deep within his territory and lost forever the image of cavalry superiority. Weeks later, during the Gettysburg campaign, Stuart set off on another encircling raid. He captured or destroyed supplies and wagons, but he also left Lee blind and deaf to the whereabouts of a fast-moving Army of the Potomac. Some historians blame Lee for giving Stuart vague orders. Others criticize Stuart for leaving Lee for an extended period while behind enemy lines.84

In 1864, while the Army of Northern Virginia was fighting for survival at SPOTSYLVANIA, Stuart intercepted Union cavalry a dozen miles from Richmond. As Stuart directed his men on the front lines, a retreating Federal put a bullet in his abdomen. The following day Stuart was dead at age thirty-one of peritonitis. Upon hearing the news, Lee wept repeatedly.

Reflective of his youthful chides, Jeb Stuart nicknamed fellow officer William Hullihen “Honeybun.”

7. George H. Thomas (U.S., Virginia, 1816–70)

The pinnacle of professionalism, George H. Thomas was unshakable, calculating, reserved, loyal to his men and his superiors, and probably the best defensive general on either side. He tolerated nothing but the most professional behavior from himself and others and habitually worked near the front lines. Thrice his troops saved the Union from devastating losses and twice nearly obliterated the Army of Tennessee. Yet, for being Virginia-born and hesitant to attack, he was also a target of suspicion from many in the Union, including ULYSSES S. GRANT.85

A veteran of the Seminole Wars and the Mexican War, a West Point instructor in cavalry and artillery, at six feet tall and two hundred pounds, Thomas had the look and reputation of stability. This stability was put to the test at the battle of STONES RIVER, where he was one of three corps commanders under William S. Rosecrans. On the first day Confederates forced portions of the Union line three miles backward. Federal casualties exceeded ten thousand. Union corps and divisions overlapped and melted, but Thomas exuded a calm tenacity, kept soldiers supplied with ammunition, and directed a unified withdrawal to safer ground. That night Rosecrans convened a council of his officers, and several advised withdrawal. Thomas interjected and insisted: “This army does not retreat.” The Army of the Cumberland remained, and two days later were victorious.86

Thomas repeated his performance on a much larger scale at the 1863 battle of CHICKAMAUGA, when three Confederate divisions came pouring through a breach in the Federal line. A third of the Union army broke and ran, including its commander, Rosecrans. Thomas, second in command, remained steadfast and managed to keep a majority of the Army of the Cumberland on the field. By Confederate Gen. JAMES LONGSTREET’S count, there were twenty-five assaults upon the Union gap, but the Federals reformed and retreated yet did not break. What started as a rout became a withdrawal of cohesion. Known before as Old Tom, Slow Trot, and Pap, Thomas became nationally renowned as the Rock of Chickamauga. Lincoln said of Thomas’s performance, “It is doubtful whether his heroism and skill…has ever been surpassed in the world.”87

Thomas’s finest moment came days before he was about to be removed from command. After the 1864 battle of FRANKLIN, where JOHN BELL HOOD’S Army of Tennessee suffered horrid losses by attacking Union trenches, Hood moved toward the Tennessee capital, where Thomas and sixty thousand Federals were stationed. Hood dug in and waited, hoping Thomas would attack him.

Grant hounded Thomas to strike the weakened Confederates. Telegraph after telegraph threatened Thomas with dismissal if he did not move. The Rock apologized but informed Grant that a lack of horses and two successive ice storms jeopardized any assault. Days turned into weeks, and Grant feared Thomas had become another McClellan.88

When the sun came out in mid-December, the Virginian proved he was no Virginia Creeper. Just as Grant planned to go westward to relieve him personally, Thomas sent forth fifty-five thousand men, jabbing Hood’s right flank then smashing into his left. In two days, with a supremely organized offensive, Thomas inflicted more than six thousand casualties (twice as many as he received) and pushed Hood out of Tennessee. The once great Confederate army of the west had fought its last major battle.89

In 1831 Nat Turner’s Rebellion ravaged Southampton County, Virginia. The largest slave revolt in U.S. history killed more than sixty whites in two days. Some of the residents managed to escape in time, including fifteen-year-old George H. Thomas.

8. Philip H. Sheridan (U.S., New York, 1831–88)

At five foot five inches and 115 pounds, with stout legs, tight black hair, and eyes set in a permanent scowl, the West Pointer had the physique and look of kinetic intensity. Shy as a youngster, he grew into a nervous, judgmental, sometimes vicious adult who rarely offered any measure of forgiveness. In milder terms, Sheridan was a shrewd perfectionist. He began the war as a quartermaster and commissary officer. Precise and efficient, he was also very much a soldier’s soldier. He worked relentlessly to provide enlisted men with the best weapons and rations available. A Sheridan trademark, he never shied away from a fight with fellow officers, even his superiors, if he thought they were neglecting their men.90

Achieving a field command in May 1862, Sheridan revealed a dichotomous nature. He became calm when people panicked, and furious when others were complacent. On the first day of STONES RIVER, Confederate attacks sent two Federal divisions flying rearward. Sheridan’s division resisted the onslaught. He lost all three of his brigade commanders and 40 percent of his men, the worst losses he would ever experience in the war. Yet his steady and belligerent withdrawal helped Union lines reform and eventually launch a successful counteroffensive.91

In contrast, his greatest victory and purest display of temper may have been at the October 1864 battle of Cedar Creek. Impressed by the proficient and ferocious Sheridan, Grant gave him command of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry and the responsibility of conquering the Shenandoah. The young Sheridan set in motion a scorched-earth policy, killing or confiscating livestock, burning grain, destroying barns. He even struck at the farmsteads of pacifist Quakers and Dunkers, reasoning that anything left could potentially benefit the enemy. While Sheridan was returning from a conference in Washington, some eighteen thousand Confederates under Jubal Early attacked and routed Sheridan’s thirty thousand. Sheridan arrived on the field to see his men dejected and resigned. Exploding into fury, swearing at the top of his lungs, he rode through his troops and fashioned a spirited counterattack. In an afternoon Sheridan’s men recaptured all the ground they had lost and took most of Early’s artillery, wagons, ambulances, and ammunition.92

Up to that point the Shenandoah had been where Union military careers, and thousands of Federal troops, had gone to die. In 1862 NATHANIEL BANKS, JOHN C. FRÉMONT, and Irvin McDowell failed to take it. In early 1864 Franz Sigel and David Hunter also faltered. Then, after months of ruthless destruction and a moment that became known as Sheridan’s Ride, the Valley was effectively in Union hands for good.

Sheridan would go on to lead his horse soldiers in the pursuit and capture of the Army of Northern Virginia near Appomattox Court House.93

Among the Union officers who personally witnessed Sheridan’s Ride were future presidents Maj. William McKinley and Col. Rutherford B. Hayes.

9. Patrick Cleburne (C.S., Ireland, 1828–64)

Brave, beloved by his soldiers, and one of two men of foreign birth to rise to major general in the South, Patrick Cleburne remains a sentimental favorite among Civil War historians—and for good reason. He evolved from a complete incompetent to the most adept, farsighted, and fierce division leader of the Confederacy.94

As a youth in his native Ireland, the serious and reserved fellow showed little promise. Academics were not his strong point. He served briefly in the British army with no distinction. He then immigrated to the United States in 1849 and joined the Confederate army when his adopted Arkansas seceded.

Leading a brigade at SHILOH, Cleburne’s performance was deplorable. Starting with twenty-seven hundred men, he ordered a series of attacks that made no impact upon strong defenses. The second day he was down to eight hundred, and he again attempted a reckless charge. By battle’s end, all but fifty-eight of his men were captured, wounded, missing, or dead.95

Rather than blame his superiors, he reassessed everything he knew about warfare. Coordinating with his junior officers, he paid greater attention to organization and supply. Before battle, he used sharpshooters to probe and reduce enemy positions. If an attack was ordered, he advanced using the protection of terrain and concentrated his firepower rather than simply launch a massed charge.96

Cleburne’s revised methods brought success to BRAXTON BRAGG’S otherwise dismal 1862 campaign into Kentucky. In a fight for Richmond, Kentucky, Cleburne’s men captured hundreds of Federals. At Perryville, Cleburne again pushed into enemy lines with success, until Bragg ordered a retreat. As mule- and horse-drawn wagons struggled over the hilly escape route, Bragg ordered the wagons and twenty thousand rifles therein destroyed. Cleburne instead ordered teams of men to carry the load up the steep inclines. He and his men escaped with the cache intact.97

In the New Year’s fight at STONES RIVER, Cleburne’s division was the most successful in pushing back the Union line, only to be pulled back when attacks failed on other sections of the front. When Sherman’s blue wave swept Bragg from Chattanooga in late 1863, it was Cleburne and his division who held on, refusing to budge from the north edge of Missionary Ridge. To clear this last obstacle, the Federals concentrated their forces upon him, and still Cleburne’s outnumbered and outgunned men did not give way. Only when he learned of the demise of the rest of Bragg’s army did Cleburne order a withdrawal, and while doing so fought vicious rear-guard actions against Federals three times his numbers.98

Hating the pomp and elitism often accompanying his grade, Cleburne was an odd mixture of practicality and ice-cold bravery. During standoffs in battle, he would personally roam into no man’s land to retrieve discarded weapons. In hopes of securing British and French diplomatic recognition and to strengthen the depleted army, he was the first Confederate general to propose liberating and arming slaves. Dubbed the Stonewall of the West, he received a fine compliment from a man normally averse to showering praise; ROBERT E. LEE called him “a meteor shining from a clouded sky.”99

Able to succeed in spite of serving under the likes of Bragg and LEONIDAS POLK, the quiet but driven man from Ireland did not live to see the end of the war. Cleburne was one of six Confederate generals to die at the slaughterhouse of Franklin. He was within reach of the Union lines when he was shot through the chest.100

At the battle of Richmond, Kentucky, a minié ball hit Cleburne in the side of the face, smashed two teeth, and exited past his lips. In a rare show of humor, he later joshed that he caught the Union bullet in his mouth and spat it right back out.

10. Nathan Bedford Forrest (C.S., Tennessee, 1821–77)

With no military experience and six months of formal education, this Tennessee plantation owner fused a talent for leadership with a penchant for violence and rose from a private to lieutenant general. Arch-nemesis WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN called him “the most remarkable man our Civil War produced on either side.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest was almost forty years old when he joined the Seventh Tennessee. Standing six feet two inches tall, the driven and imposing Forrest became impatient with lesser men. To rectify the situation he raised and equipped a mounted battalion with his own money. The battalion fittingly elected him their commanding officer.101

Ineloquent, barely literate, his lack of education embarrassed and frustrated him, yet it may have been one of his greatest strengths. Understanding only the basics of military tactics, he in turn communicated them in their most basic terms. As a result, his men knew quickly and exactly what to do. Common phrases included, “Get there first with the most” (attain the high ground with superior forces), “Bulge ’em” (conduct feinting attacks), “hit ’em on the end” (attack the enemy flank), or “mix with ’em” (establish close quarters and eliminate artillery opportunity).

A battle near Guntown, Mississippi, exemplified his tenets on combat. Learning that eight thousand Federals (including three thousand cavalry and eighteen guns) were coming from Memphis to subdue him and his thirty-five hundred men, Forrest assessed the situation. The area near Brice’s Crossroads was heavily wooded, which could hide his inferior numbers. He could use feints to hold the advance column of Federal cavalry until his entire force moved into place. For the Union infantry to arrive in time, they would have to march quickly through narrow, muddy roads on a brutally hot and muggy day. The Northern boys would become exhausted, strung out, and therefore susceptible to flank attacks. With the enemy so deep in his territory, Forrest could follow up any success with unmerciful pursuit.

The engagement transpired almost precisely as he predicted. Forrest’s men bagged all but two Federal cannon, nearly every wagon, plus food, weapons, horses, and more than sixteen hundred prisoners.102

In contrast, his most infamous act is undoubtedly the butchery at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. On April 12, 1864, Forrest and his men surrounded a Federal garrison stationed on the Mississippi near Memphis. After a short battle, the fort surrendered. Angered by the presence of three hundred African American soldiers among the garrison of nearly six hundred, the victorious Confederates began to kill prisoners, including the wounded. More than two hundred Federals perished, plus another one hundred were seriously wounded. Forrest lost just fourteen killed. Though the actions were excused by the Confederate government as a natural result of battle, and condemned in the Union as a massacre, evidence suggests the latter. Although not ordering the killing, Forrest expressed no remorse for the incident.103

Ingenious in limited operations, Forrest’s tangible contribution to the Confederate effort was relatively small. A common observation about this otherwise brilliant tactician was that he played a large part in small battles and a small part in large battles.

In April and May 1863 Forrest pursued a long-range Union raid into Alabama led by Col. Abel D. Streight. On May 3 he cornered his prey, roughly fifteen hundred Federals, with only six hundred men. To mask his inferior numbers from Streight, Forrest shifted a single gun in and out of sight several times while negotiating surrender terms for the Federals. After capitulating and discovering the ruse, Streight protested. Forrest replied, “Ah, Colonel, all’s fair in love and war.”

Compared to other military conflicts, the American Civil War was not unique in its display of inept military leadership. If anything, the war’s duration of four long years provided time for corrective measures. A number of underachieving generals resigned of their own accord while others progressed from mediocrity to varying degrees of competence. To monitor poor performers, Confederate officials created a Bureau of the War while the Federals constructed the sometimes helpful, sometimes libelous Committee on the Conduct of the War. Wounds, disease, and accidents pruned several more bad generals, but there remained a wide array of individuals worthy of harsh criticism.104

Perhaps hundreds of generals were less competent than the ten listed here. These ten, however, lost more ground, created more problems, squandered more time, and achieved fewer gains with more men than any other commanding officers in the war. Some failed through recklessness, others by receding. Some communicated too little while others said far too much. A few spent all of their time preparing while others prepared not at all. Each man won at least one battle. Not one indicated he knew how to win a war.

1. Braxton Bragg (C.S., North Carolina, 1817–76)

With thatch brows, dark eyes, and thistle beard, Braxton Bragg’s countenance was appropriately that of a cornered animal. To his subordinates, he was vindictive, contrary, and deceitful. In combat he repeatedly committed horrible mistakes. He ruled by fear and executed scores of his soldiers for slight infractions. Although few could question his bravery, Bragg often questioned everyone else’s, yet he maintained the trust and devotion of a powerful army buddy, Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

The tragic play began in 1862 at SHILOH, where Bragg ordered several small, unsupported bayonet charges into well-defended artillery positions. When his men were summarily slaughtered, he blamed their immediate officers. For his brazen aggressiveness, Bragg received a promotion.105

Later in 1862 Bragg initiated a campaign into Kentucky with no clear objectives. Encountering heavy opposition at Perryville, he again employed piecemeal attacks and again lost lives with no result, abandoning more than three thousand of his dead and wounded on the field. Bragg’s tactics were so inept and baseless, fellow officer Henry Heth feared Bragg had “lost his mind.”106

In overall command at STONES RIVER, Bragg finally attempted a unified attack—over completely unsuitable terrain. Several regiments became easy targets as they advanced across open ground. Others had to sift through heavily wooded areas, losing contact with their support flanks. Miraculously, his men achieved early successes, but Bragg followed up with uncoordinated forays upon the best-defended section of the enemy line. Of the eighty-eight Confederate regiments at Stones River, twenty-three of them suffered 40 percent casualties or more. According to Bragg, victory evaded him because his officers displayed neither courage nor cooperation.107