ROBBEN ISLAND MAXIMUM SECURITY PRISON

JUNE 1964–MARCH 1982

Within hours of being sentenced to life imprisonment, Nelson Mandela and six of his comrades were taken from their cells in Pretoria Local Prison, handcuffed, and driven to a nearby military air base. They arrived on Robben Island early the next morning, Saturday, 13 June 1964. Denis Goldberg, the only white accused convicted with them, remained in Pretoria to serve his sentence – apartheid laws decreed that he was forbidden from being incarcerated with black prisoners.

This was Mandela’s second time in Robben Island maximum security prison; his few weeks as a prisoner there in mid-1963 had prepared him for the harsh conditions, and he counselled his comrades on the importance of keeping their dignity intact.

Soon after he and three others had arrived his previous time on Robben Island in May 1963, prison guards barked orders for them to walk briskly in twos, herding them like cattle. When they continued walking at the same pace, the guards threatened them. ‘Look here, we will kill you here – and your parents, your people, will never know what has happened to you,’ Mandela recalled them saying. He and Steve Tefu, a prisoner who belonged to the PAC, then took the lead, maintaining their own pace. ‘I was determined that we should put our stamp clearly, right from the first day we must fight because that would determine how we were going to be treated. But if we gave in on the first day, then they would treat us in a very contemptuous manner. So we went to the front and we walked even more steadily. They couldn’t do anything, they didn’t do anything.’40

Conditions on Robben Island were brutal. The prisoners were only allowed to stop doing hard labour fourteen years later in 1978, and until then their existence on the island was stark and cruel, lightened only by their own attitude, as well as visits and letters from family.

In the beginning, the food was barely ediblei and divvied up according to racist policies. Breakfast for African prisoners was 12 ounces of maize meal porridge and a cup of black coffee, so-called coloured and Indian prisoners got 14 ounces of maize meal porridge with bread and coffee.41 There were no white prisoners on the island.

‘We were like cattle kept on spare rations so as to be lean for the market,’ prisoner Indres Naidoo writes. ‘Bodies to be kept alive, not human beings with tastes and a pleasure in eating.’42

The weather conditions on the island were extreme – ‘blistering hot in summer’ and in winter ‘bitterly cold, raining or drizzling most of the time’, recalled former prisoner Mac Maharaj.43 In the beginning, African prisoners had to wear short pants and sandals year-round, whereas Indian and coloured prisoners were issued with long pants and socks.i Prisoners were given a thin jersey on 25 April, which was taken away again on 25 September.44 There were no beds for the first ten years – prisoners slept on the concrete floor on a sisal mat with three ‘flimsy’ blankets.45 It was so cold in winter, they slept fully clothed. For the first ten years, Mandela and his colleagues bathed with cold water.

Throughout the week, prisoners were put to work in the yard, breaking stones with hammers. On the weekends, they were locked in their cells for twenty-three hours a day, unless they had a visitor. At the beginning of 1965, they were set to work digging in the lime quarry.ii It was gruelling work, and the glare of the sun on the white limestone seared their eyes. For three years, repeated requests to the prison authorities for dark glasses were rejected. By the time permission was given, the eyesight of many of the prisoners, including Mandela’s, had been irreparably damaged.

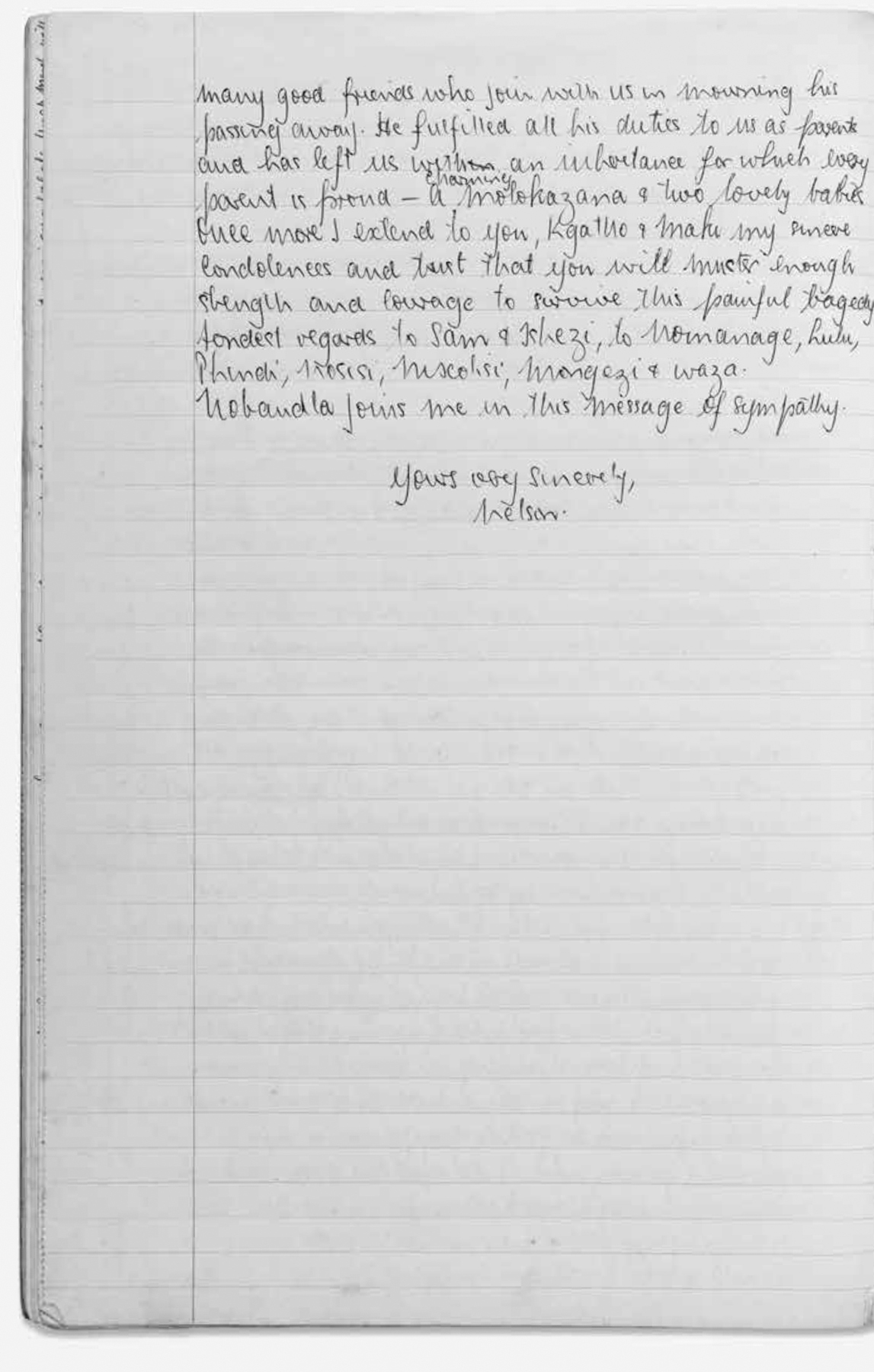

In 1968, Mandela’s mother, Nosekeni, died, and he was refused permission to bury her. The following year, his eldest son, Thembi, was killed in a car accident, and this time his plea to be at the graveside was ignored. He was forced to stand on the sidelines while friends and relatives played his role in the burials. His letters during this period spell out his raw anguish over these tremendous losses.

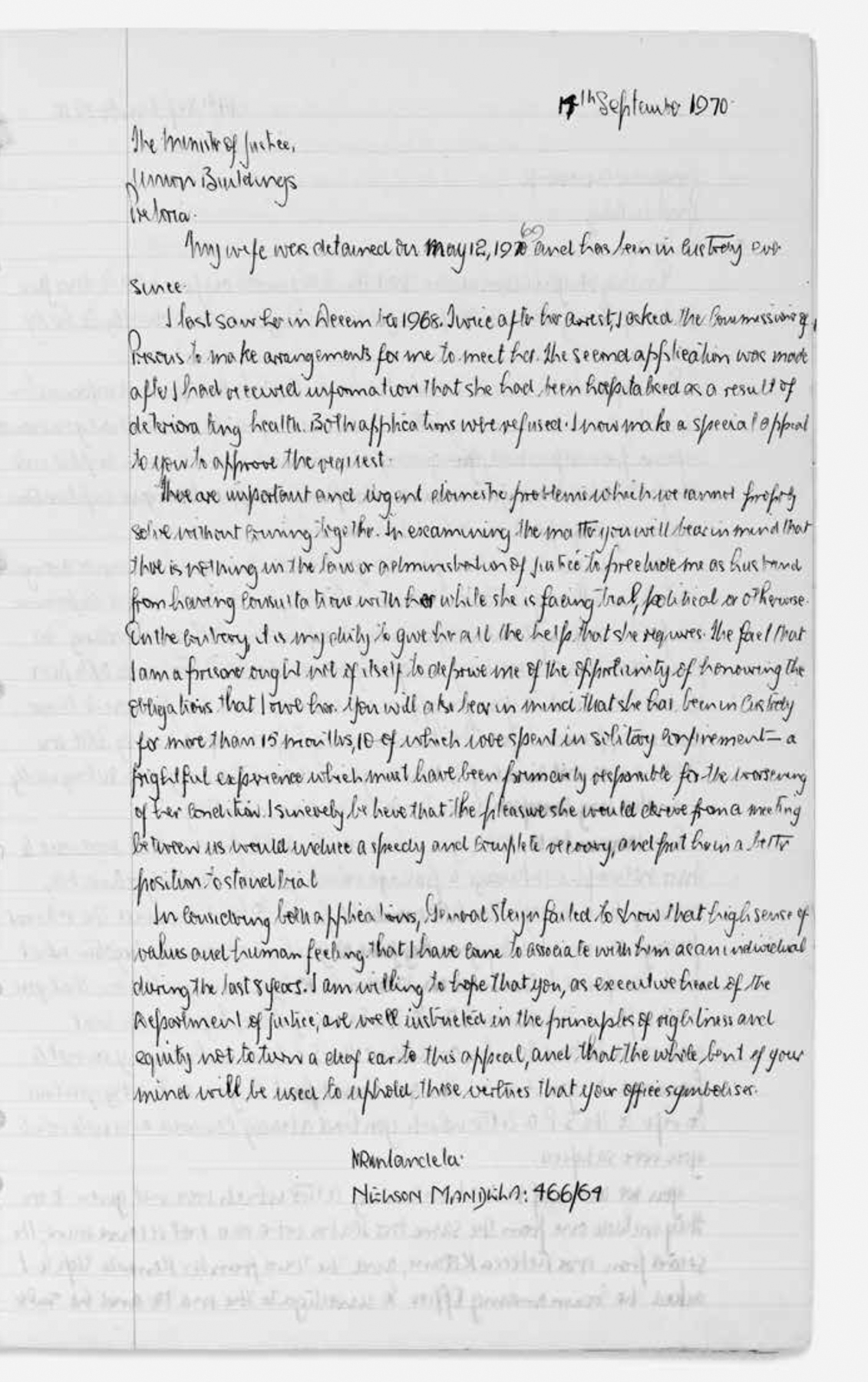

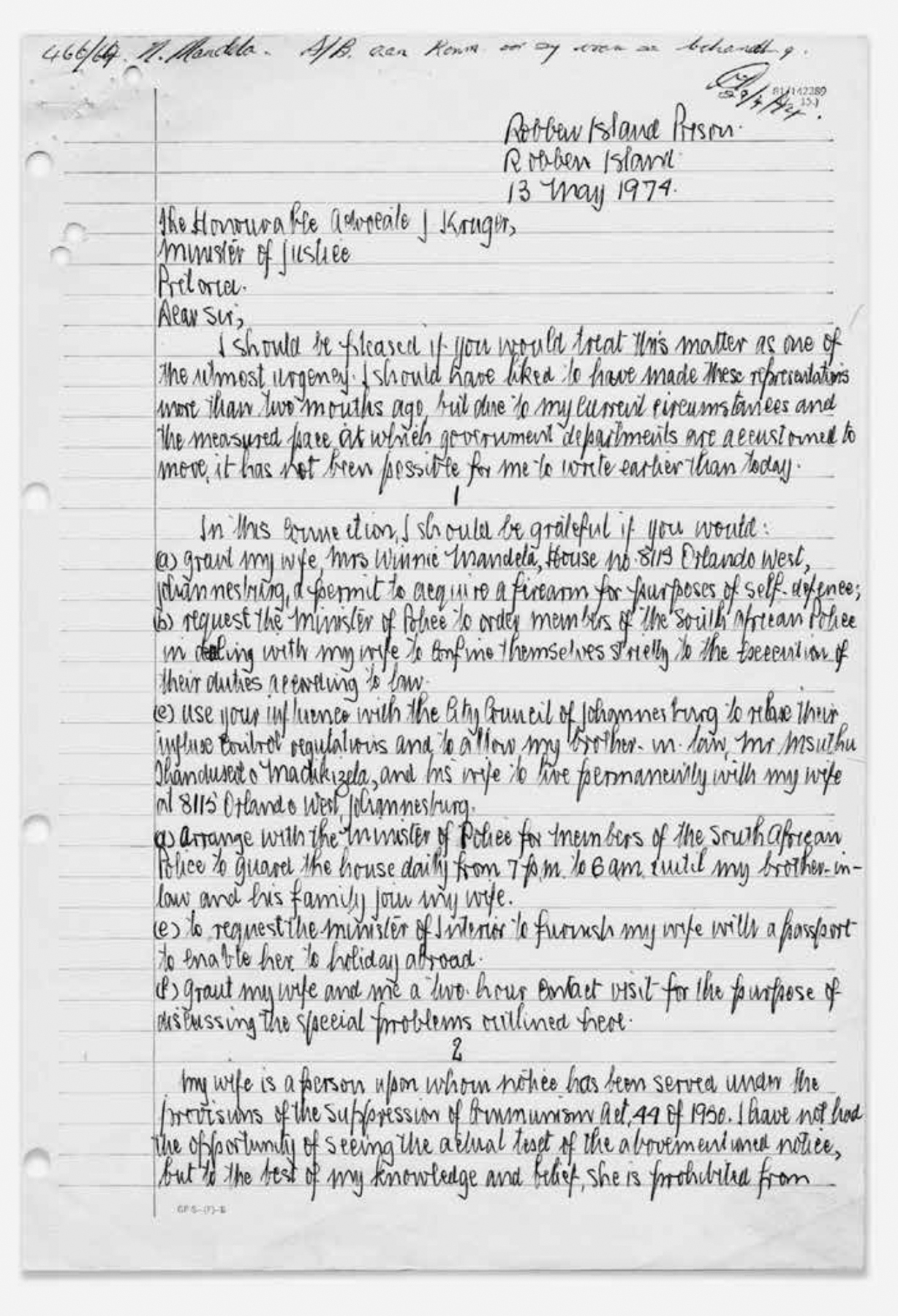

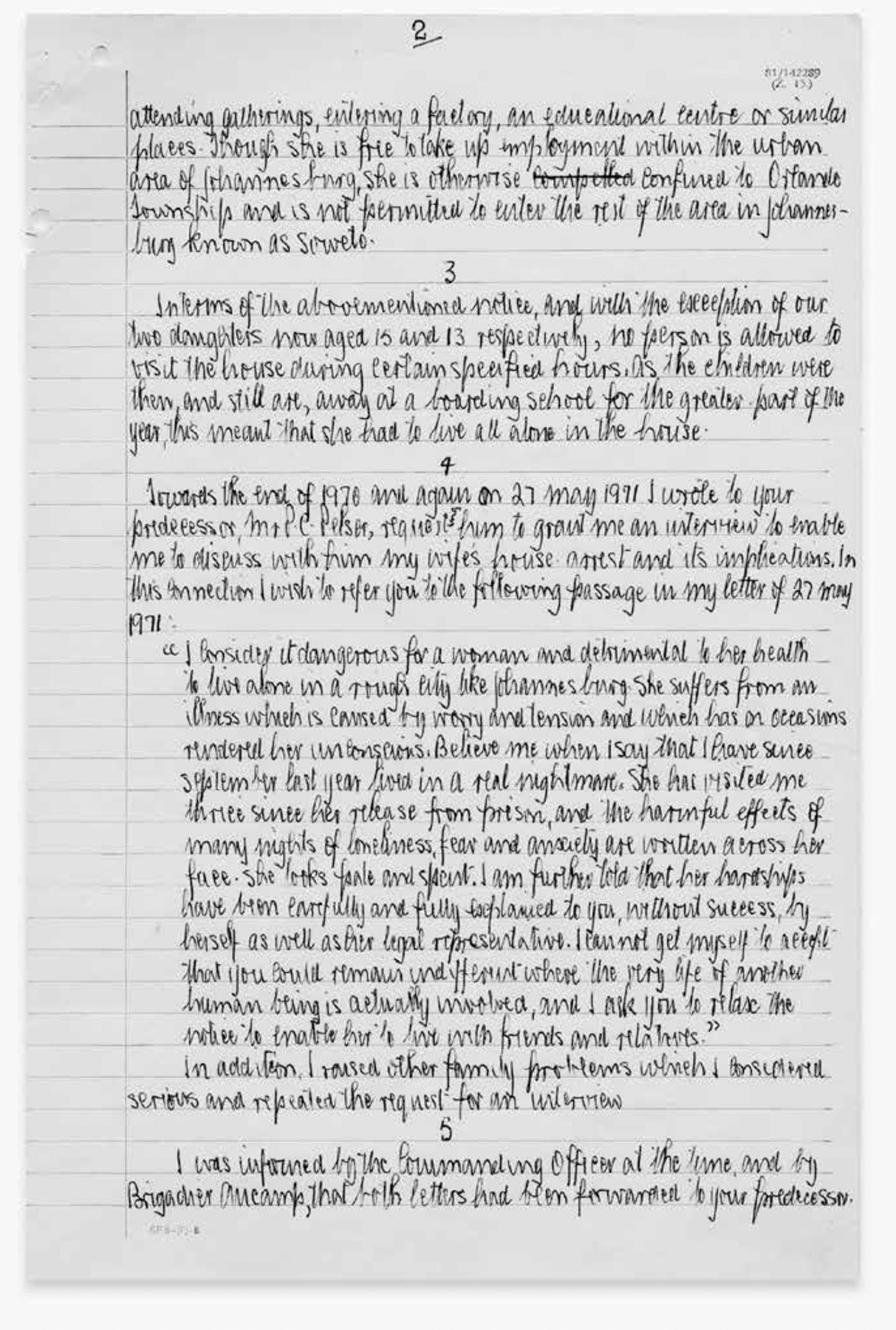

Around the same time, his beloved wife Winnie was detained by police and spent fourteen months in custody. His letters to her and others about her imprisonment demonstrate his frustration and anguish at not being able to help her or his children during this nightmare.

He kept up a regular correspondence with prison authorities to assert his rights as a prisoner, and even went as far as to demand the release of himself and his comrades or to be treated as political prisoners of war (see his letter to L. Le Grange, the minister of prisons and police, 4 September 1979, page 383).

In 1975, on the initiative of his comrades, he began to secretly write his memoirs with the assistance of Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, and two other comrades and prisoners, Mac Maharaj and Laloo Chiba. The plan was for the autobiography to be published abroad in time for his sixtieth birthday on 18 July 1978. On his release in late 1976, Maharaj smuggled off the island, hidden within the covers of notebooks, a transcribed version of the manuscript. When part of the original manuscript was discovered buried in a tin near the prison block in 1977, Mandela and his comrades had their study privileges withdrawn from the start of 1978. The manuscript, however, made it to London, but it was not published until 1994 as Long Walk to Freedom.

To Frank, Bernadt & Joffe, his attorneys

[Stamp dated 15.6.64 with word in another hand reading ‘Special’ in Afrikaans]i

Messrs Frank, Bernadt & Joffe

85 St George’s Street

Cape Town

Dear Sirs,

RE STATE V NELSON MANDELA & OTHERS

We should be pleased if you would kindly advise our attorney, Mr Joffe, of Johannesburg that his clients in this matter, with the exception of DENIS GOLDBERG, are now in Robben Island.

There is a possibility that Mr B FISCHER, QC., who led the defence team is now holidaying in the city, and we would be grateful if you would advise him if his whereabouts are known to you.

Yours faithfully

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA

Bram Fischerii was a white Afrikaner advocate who defended Mandela and his colleagues in the Treason Trial of 1956 to 1961iii and in the Rivonia Trial. But more than that, he was a comrade and a good friend. He first visited the Rivonia trialists on Robben Island in 1964 to confirm their earlier decision not to appeal their conviction and sentences.

Mandela and some of his colleagues had known Fischer and his wife, Molly, well and had spent many joyful hours at their home in Johannesburg. But on that prison visit when Mandela asked after Molly, Fischer turned and walked away. After he had left the island, a senior prison official told Mandela that she had drowned when their car left the road and plunged into a river. The major gave permission for Mandela to write Fischer a condolence letter. It was never delivered.

The letter to Fischer is formal, befitting correspondence from a prisoner to his lawyer – and in this case from a prisoner who was also a lawyer. As prisoners held a special dispensation to write to their legal advisors, it would have been preferable not to create the impression that it was a personal letter, which he may not have had permission to write.

In 1965, Fischer was arrested and tried the next year for furthering the aims of the Communist Partyi and conspiring to overthrow the government. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. While in Pretoria Local Prison he was diagnosed with cancer and fell badly in 1974. The authorities finally bowed to public pressure and released him to his brother’s house from which he was forbidden from moving. He died in 1975 and the Prisons Department had him cremated. His ashes have never been located.

To Bram Fischer,53 his comrade and advocate in the Rivonia Trial

2nd August 1964

Dear Mr Fischer,

You will recall that when you visited the Island last time, you discussed with Major Visser whether it would be permissible for you to arrange for me to receive the South African Law Journal.

I have to date not received the journal and I thought it advisable to remind you about the matter, should pressure of work have made it difficult for you to make the arrangements with Juta’s & Co.

I have also not received the lecture from Wolsey Hall, London, and the law books and I would be pleased if you would kindly check up with Mr Joffe.ii

Yours faithfully

[Signed NRMandela]

Prisoner no. 466/64

Advocate A Fischer, S.A,.

c/o Innes Chambers,

Corner Von Brandis & Pritchard Sts.

Johannesburg

Throughout his imprisonment Mandela perservered with the law studies toward his LLB that he had begun as a young man in 1943. Although he was permitted to practise as an attorney with only a diploma in law, he had set his heart on achieving this goal when he was an activist studying at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. He started his three years of legal articles at the firm Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelman within weeks of enrolling as a student, and a year later he joined the ANC when he helped to found its Youth League. From 1944 he was married to his first wife, Evelyn Mandela, and quickly the family grew, stretching his meagre finances to the limit. His application to the university in December 1949 to rewrite the final year exams he had already failed three times was rejected.

Even after passing the attorneys’ admission exam on 8 August 1951, he pushed to continue his LLB. Despite his leading role in the Defiance Campaign of 1952i he tried again to persuade the University of the Witwatersrand to take him back, until, on his thirty-fourth birthday, I. Glyn Thomas of the University wrote to him saying he had been excluded from classes until he paid the £27 he owed.

While imprisoned at Pretoria Local Prison in 1962 he signed up to London University to continue his studies, and faced challenges at every turn. Studying at night after almost eight hours toiling in the quarry, digging out lime from 1965 to 1978, was not his biggest obstacle. His correspondence reveals that he often did not receive the correct study materials or not on time. The scenario he would sketch for university officials from the University of London, and during his subsequent studies through the University of South Africa, went on for many years. He finally achieved the degree in 1989, months before his release from prison.

To the commanding officer, Robben Island

30th November 1964

The Commanding Officer

Robben Island

URGENT

I must pay today Rd 16.0 to the Cultural Attache, British Embassy, Hill Street, Pretoria, in respect of examination entry fees for Part I of the Final LL.B of the University of London.

Last month I wrote to the university for the entry forms and to my wife for the necessary funds. On the 9th of this month, I wrote a further letter to the Cultural Attache for the forms. In neither case have I received an acknowledgement or reply.

I am writing to ask you to wire today Rd 16.0 to the Cultural Attache and to ask him to send me the forms for completion. I may not have sufficient funds for this purpose, and Ahmed Kathrada, Prisoner No. 468, would be prepared, subject to your approval, to cover the entry fees and costs of the telegram.

As the entries for these examinations close today, I shall appreciate it if you would kindly treat the matter as extremely urgent.

Nelson Mandela

[Signed NRMandela]

Prisoner no. 466/64

[A note in English in red pen and in another hand] I have no objection to the wiring of the R16.00 but I am not prepared that prisoners can borrow money from each other. [Initialled and dated 30.11.]

Mandela studied the Afrikaans language in prison in search of a better knowledge of the history and culture of the ruling National Party and its followers. He believed this would help him to communicate more effectively with his enemy.

It worked. It assisted in breaking down barriers with prison guards and later with government officials and even the country’s president, P. W. Botha.i

Here, while making the point that legitimate requests are often ignored, he is reiterating his plea to be able to prepare for his exams by studying past papers of an organisation which promoted Afrikaans, an official South African language from 1925, as well as asking for back copies of an Afrikaans-language women’s magazine, Huisgenoot.

To Major Visser, prison official

[Stamp dated 25.8.1965]

Major Visser,

During the inspection on the 14th August 1965, I tried to speak to you but you did not give me the opportunity of doing so. While the inspection was in progress Chief Warder Van Tonder, who accompanied you, promised to tell you that I had some requests to make, but you left without seeing me. I am now writing to you because the matter has become urgent.

1. I am preparing to write an examination on the 29th October 1965. In March this year and early in May, I had made written applications to the Commanding Officer for leave to order old examination papers from the Saamwerk-Unie of Natal as part of my preparation for this examination. You have repeatedly assured me that you have written to the SWU and ordered the required papers and that you awaited their reply. Although the examination is now 2 months away I still have not received the papers.

2. I owe the University of South Africa the sum of R40.0 being the balance of fees for an Honours Degree course which I had planned to write in February 1966. In terms of the contract this amount must be paid before the 1st September 1965. On the last occasion I discussed the matter with you, you informed me that you had written to the university. A few days ago, I received the account for this amount and I am anxious to have the matter finalised before it is too late. In this connection I might add that I ordered my study books from Messrs Juta & Co. I asked them to order them if they did not have them in stock and to advise me when they would have them available to enable me to plan my work. I have not heard from them and I would be glad if you would kindly advise me whether the matter has been attended to.

3. You also told me that you had ordered the old Huisgenooti numbers I required for purposes of study and I wish to remind you that I have not yet received them.

4. Several times last year and early this year I applied for a loan of books from the State Library and for enrolment forms. I have not heard from them.

I am seriously considering whether in view of the difficulties I have mentioned above, I should write the forthcoming examinations, and I should be pleased if you would give me the opportunity to discuss the whole matter with you.

[Signed NRMandela]

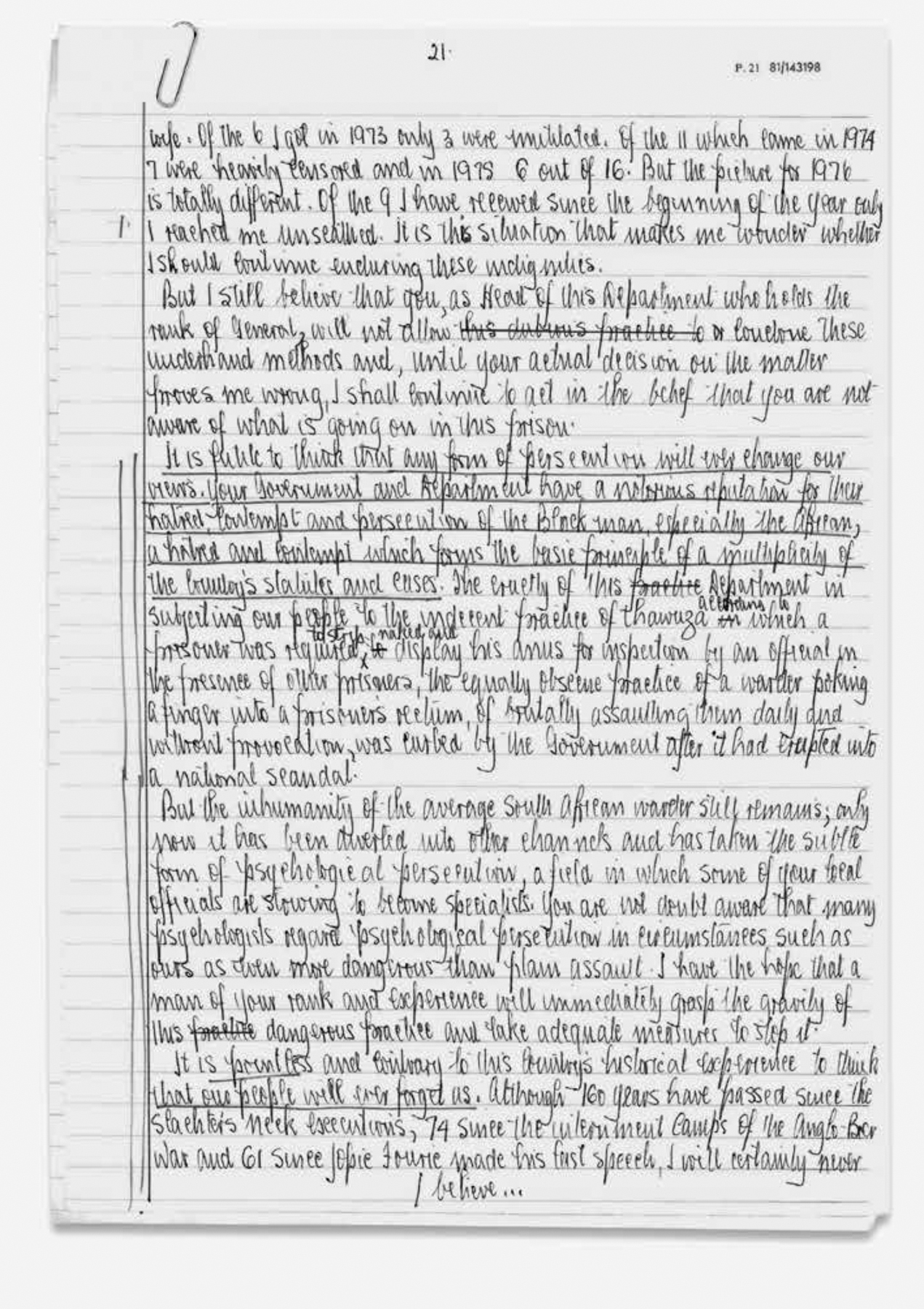

To the commissioner of prisonsii

The Commissioner of Prisons

PRETORIA

I am grateful for the concession you made on the 13th October 1965, when you informed me that you had no objection to us exchanging study books among ourselves. This relief will considerably reduce the expenses for prescribed textbooks, which most of us cannot afford, and will make available to all those who are studying more adequate sources of information and reference.

If the privilege to study is to be of any value, certain conditions are absolutely essential. Their importance applies to all students, especially to those who have to pursue their courses by correspondence and, therefore, lack the all-important direct communication between teacher and student. Academic assistance in the form of recommendation of literature, exchange of ideas, constant and personal review and criticism is implied amongst the students who have the opportunity of direct and free communication with their teachers and fellow students. Indeed correspondence colleges, as well as the University of South Africa, try in some measure to eliminate the obvious disadvantage suffered by their students by arranging annual vacation schools and emphasizing their importance to students.

For prisoners preparing themselves for the same examination as people who are able to take advantage of such vacation schools and other forms of direct and unrestricted communication with their tutors, other experienced academicians and other students, the permitting and encouraging of mutual assistance among prisoners themselves would be a reasonable measure of compensation and entirely compatible with the Prisons Act. Such mutual assistance would involve free discussions on [the] part of [the] prisoner with others who are able to assist him. This would apply especially where he is studying language, law and the Humanities. Discussion sharpens one’s interest in any subject and accordingly inspires reading and corrects errors. The cumulative effect of all this would be to facilitate the retention in the mind of what has been read.

Moreover, the preparation of exercises and essays for others to correct and advise on would be a constant stimulus to the student who otherwise could not have a proper check on his progress. In both respects, prisoners, particularly in this prison, are at a tremendous disadvantage and one in which they will never attain parity with other students outside to whom are available adequate facilities. In this connection I would point out that in 1963, while at the Pretoria Jail, I started a language course and I took advantage of the prison school there. I found it very helpful in correcting my mistakes and in enabling me to pick up the language fairly quickly.

To allow us free discussion and the other forms of assistance discussed above would, taken together with the concession you have already made, go a long way to remove our present difficulties. In this regard I would like to repeat the undertaking I made to you on the 13th instant that we will endeavour not to use the concessions you have already granted, as well as those you may still grant, for any improper purpose.

Finally, I would like to refer to your decision rejecting the request I made on the 14th March 1965 relating to the account for the eye test. No reasons were furnished for the refusal and I am consequently unable to give you fresh reasons to support my request. I would, however, ask you to reconsider the matter afresh and grant me the relief asked for.

[Signed NRMandela]

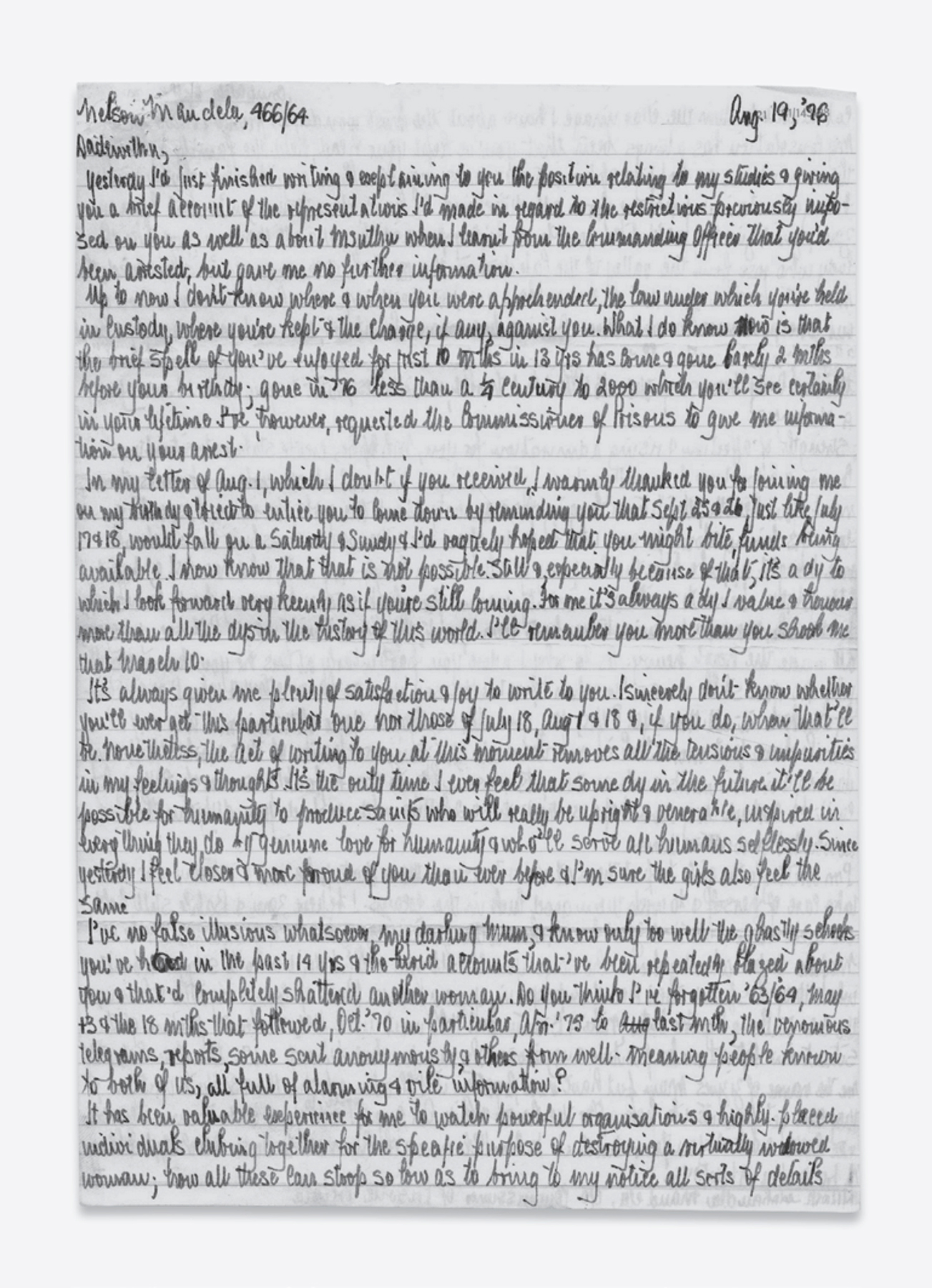

Apart from the letters they were allowed to write to officials and their lawyers, prisoners could only initially write to direct family members. In the beginning it was one letter of 500 words every six months. They were also only allowed one family visit every six months. Children over two years old could only visit their fathers when they turned sixteen. By the time of Mandela’s first imprisonment in 1962, his five children – two boys and three girls – were aged between twenty-three months and seventeen years old. He mentions all five in this letter: Thembi, Makgatho (Kgatho), Maki (Makaziwe), Zeni (Zenani) and Zindzi (Zindziswa). The first three were born during his first marriage to Evelyn Mase and the youngest two during his marriage with Winnie Madikizela.

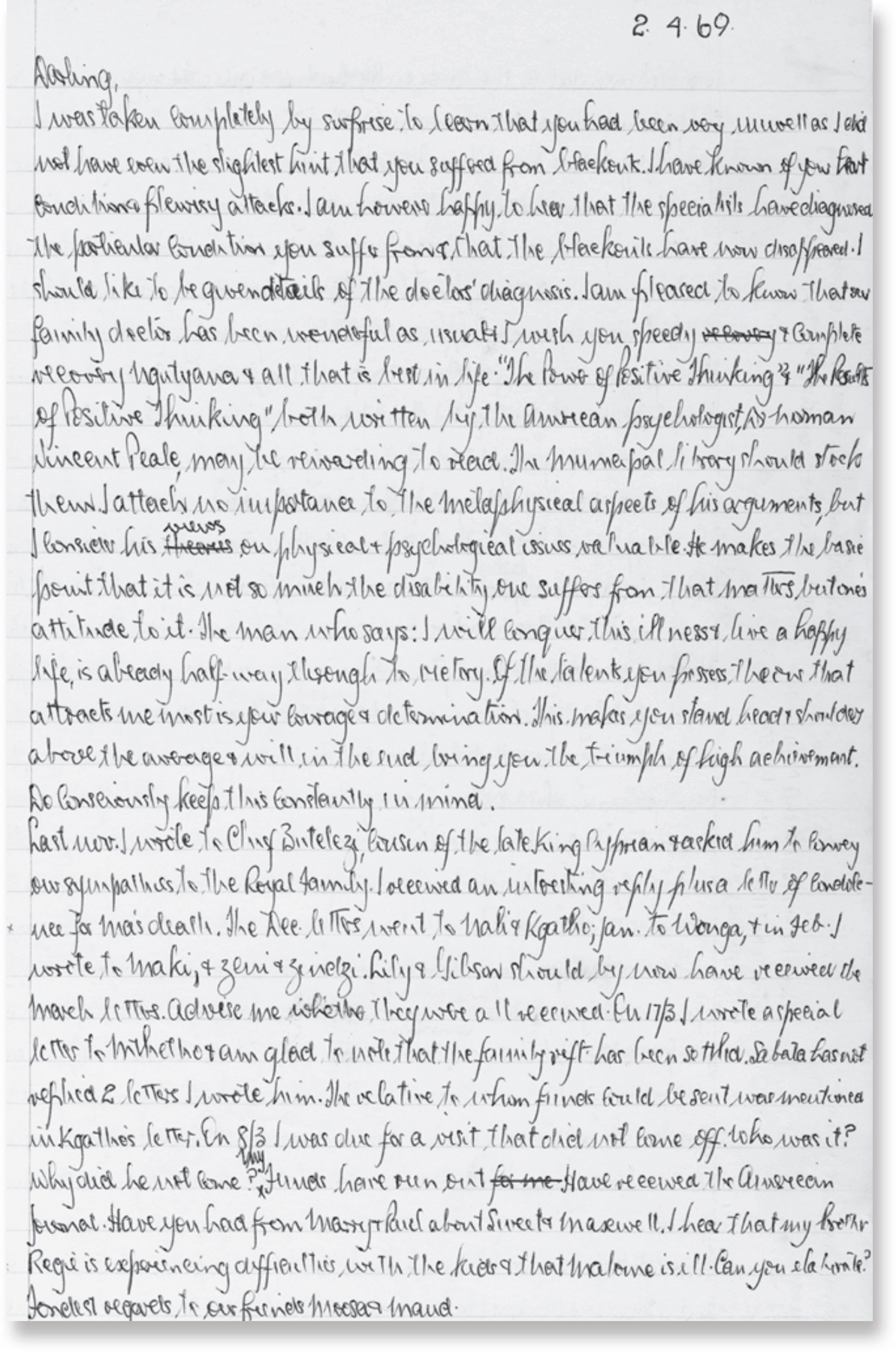

To Winnie Mandela,i his wife

[In another hand it says ‘Special letter’]ii

When replying put at the top of your letter “Reply to special letter”iii

NELSON MANDELA No 466/64

17 February 1966

Darling,

I should be pleased if you would kindly instruct Messrs Hayman & Aronsohn not to proceed with the action against the Prison Authorities.

On the 8th February 1966 I had an interview with the Chief Magistrate of Cape Town who came on the instruction of the Secretary for Justice. He asked me to give him an affidavit relating to any complaints or representations that I wished to make on my treatment. I was unable to give him an affidavit, but I gave him a written statement in which I indicated that I was anxious to take advantage of the opportunity of repeating my representations to higher authorities. I pointed out, however, that I would like to consult my attorney on the matter.

On the 14th February I had another interview, this time with the Commissioner of Prisons, in the course of which he promised to put my requests to the Minister of Justice. It has been my attitude right from the beginning to endeavour to explore all the channels available within the Department. I accordingly decided to take advantage of the opportunity of my representations being placed before the Minister. I should, therefore, be pleased if you would kindly advise Miss Hayman of this arrangement and instruct her not to proceed, to her know that I am very grateful for her prompt action and I shake her hand very warmly. You also acted with equal speed for which I compliment you.

I have now received Niki’si 2 telegrams and was shocked by the news of C.K’sii illness and greatly relieved to learn of his recovery. Do write and tell him that I wish him complete recovery and many years of good health and prosperity. The Commanding Officer has given me permission to receive a letter from Niki, and I should be pleased if you would kindly tell her to write.

I have passed the Hoër Afrikaanse Taaleksamensiii and have now enrolled for Afrikaans-Nederlands Course 1iv with the University of South Africa. The fees and cost of text books have been prohibitive and my funds have run out. Tell G. Please do not pay from your account.

Your Xmas card could not be traced Mhlope.v I hope you received my January letter. I had written to Nkosikazi Luthulivi on New Year and I got an inspiring reply. I will keep it for you.

The law exams begin on the 13 June, the day before our 8th wedding anniversary. This is a very difficult period of hard and heavy swotting. It will be such a relief when it is all over at last. I hope you have not abandoned your studies and that in your next letter you will be able to report progress.vii

My love to Niki and Uncle Marsh,viii Nali,ix Bantux and hubby, Nyanyaxi and all our relatives and friends. Do tell Nali to pass my regards to Sefton.xii

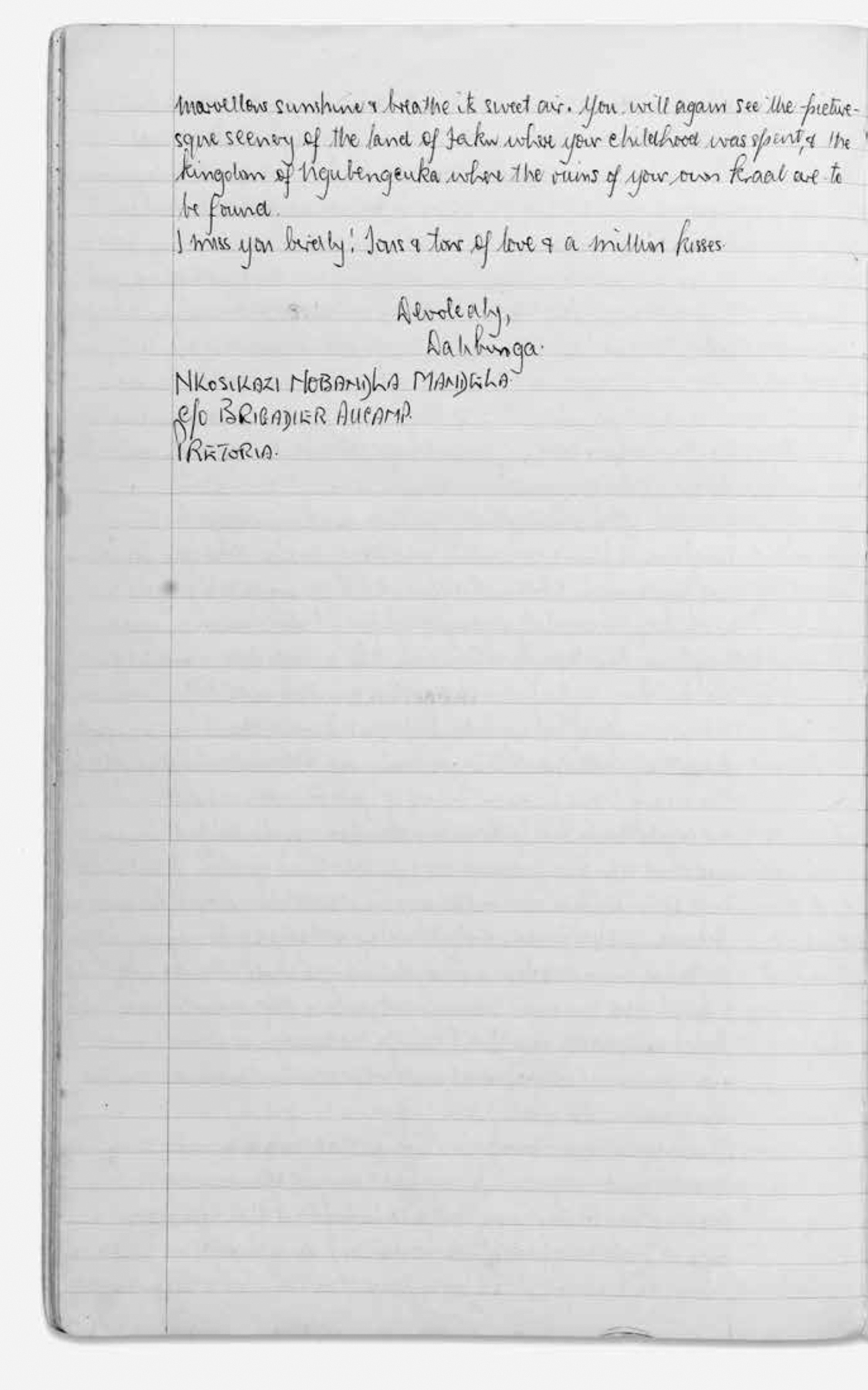

Tons and tons of love to you darling and a million kisses. Tell Thembi, Kgatho, Maki, Zeni and Zindzixiii that I miss them very much and that I send my love.

Devotedly,

Dalibunga

Nkosikazi Nobandla Mandela,

House no 8115, Orlando West,

Johannesburg

Still struggling to receive study materials, Mandela writes directly to the registrar of the University of South Africa, using the man’s native tongue of Afrikaans. This letter implies that he is aware he has the right to make such an enquiry and also displays that he has managed to maintain the dignity the prison system conspired to place from his reach. He would also have been aware that this letter would make clear to officials, particularly those in the censors’ office, that he was not prepared to give up this battle.

To the registrar, University of South Africa

[Translated from Afrikaans]

22 August 1966

The Registrar,

University of South Africa,

PO Box 392

Pretoria

Reference no MB072

Dear Sir,

Please be so good as to allow me to postpone the AFRIKAANS-NEDERLANDS exam till next year. I am struggling to obtain some of the prescribed books and I believe it to be dangerous to attempt the exam without these books.

Sincerely,

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON R.i MANDELA

To the secretary, American Society of International Law

31.8.66

The Secretary,

American Society of International Law,

2223 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

WASHINGTON D.C. 2008

20008

Dear Sir,

I have not received the July 1966 issue of the American Journal of International Law. Presumably because my subscription has lapsed.

I would have enclosed with this letter the annual subscription fee but I unfortunately do not know what amount is due because a friend had originally paid for me.

I am preparing to write an examination in Public International Law shortly and I should, therefore, be pleased if you would kindly advise me by return of post whether the subscription has expired and the amount now due.

Yours faithfully,

[Signed NRMandela]

To the commanding officer, Robben Island

NELSON MANDELA 466/64.

8th September 1966.

The Commanding Officer,

Robben Island

I have broken the lens of my reading glasses and I should be pleased if you would kindly arrange for the glasses to be sent for repairs to Dr Sachs of Cape Town who prescribed them.

Kindly deduct the costs of repairs from my account.i

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA

It is unclear whether this was a smuggled letter as the addressee, Cecil Eprile, was not a member of Mandela’s family, or whether by that stage he was permitted to write to friends. Eprile was a friend of Mandela and had been editor of the Golden City Post, a Johannesburg newspaper aimed at black South Africans. Eprile’s son, Tony, is convinced his father never received this letter. It was written at the time the Eprile family had left South Africa for London where Cecil worked as editor-in-chief of Forum World Features. They settled in the United States in early 1972.

To Cecil Eprile,i a friend and former Golden City Post editor

[in another hand] 46664 Nelson Mandela

466/64

11/2/67

Dear Cecil,

I need R150.00 for studies; may I exploit you. During the last 4 years I parasited on Winnie. She has been out of employment since April ’65 and I haven’t the heart to squeeze her further. Last year she sent me R100.00 and it has all vanished.

I must also burden you with yet another of my personal problems. My son, Makgatho, was expelled from St Christopher’s, Manzini, apparently after a student strike there. Luckily he managed to secure a first-class pass in the Junior Certificate, and I believe he now attends a local school. I fear that the sudden change may affect his progress and standard of performance. He may also be feeling lonely and unhappy here because all his sisters and friends are over there. Could you try and help him be readmitted or fixed up in another boarding school there. He is a clever fellow and should be able to catch up with others even though he may return late. I believe his health has recently become indifferent and it may be that, in the circumstances, it is considered advisable that he should not be far from Baragwanath Hospital. Perhaps it may be better to call him to your office and discuss the matter with him first and ascertain his views on the matter. You may also have a chat with Winnie; anyway I leave the matter in your able hands.

I was sorry to learn of the death of Nat,i it was a cruel blow for we regarded him with a great deal of affection. He was a man of undoubted competence and an asset to us all. Often, after reading his articles, I came away with the feeling that indeed, the pen was mightier than the sword. I hope you found somebody just as capable to replace him.

I was happy to know of the rapid growth and expansion of the enterprise you have piloted so skilfully, as well as of your own progress and achievement. I know that all of this will be embarrassing to you. But [there is a water stain over the word] the consolation that I will not be there to see you blush. As for myself I feel on top of the world in more senses than one. I am keeping well and fit in flesh and spirit and am looking forward to the day when I will again see you enjoy once more the happy moments we have spent together in the past.

My fondest regards to you and Leon and tons of love to your wifeii and Zelda.iii

Sincerely,

Nelson

PS: Please tell Winnie that in arranging the next visit, she must give preference to Madiba or Makgathoiv if she will not be coming down in person.

N

Cecil Eprile Esq,

c/o Mrs Winnie Mandela

House no, 8115 Orlando West

Johannesburg

To the commanding officer, Robben Island

27th February 1967

The Commanding Officer

Robben Island.i

I am preparing to write an examination on the 10th June 1967. Entries for this examination ought to have been received by the British Embassy by 1st December 1966. I handed in the entry forms early in November 1966 with a request that the forms together with the sum of R8.00 be sent to Pretoria.ii In spite of several enquiries I made, I am still uncertain whether my entry has now been approved.

In February 1966 I ordered prescribed text-books from a London book firm to prepare for this same examination, and although I had been assured that the money to cover the cost of the books as well as postage had been sent, I never received them. In October last year I placed another order for the same books and I still have not received them, a fact which has seriously handicapped me in preparation for the forthcoming examination. In September 1966 I had ordered from the same book firm a number of text books but my letter was posted without the necessary amount for the payment and postage of these books. I subsequently received an accountry from them after they had sent the books on credit.

I had also written to the Registrar of the University of London and requested that R1.00 be enclosed in my letter. I have received no reply to this letter either.

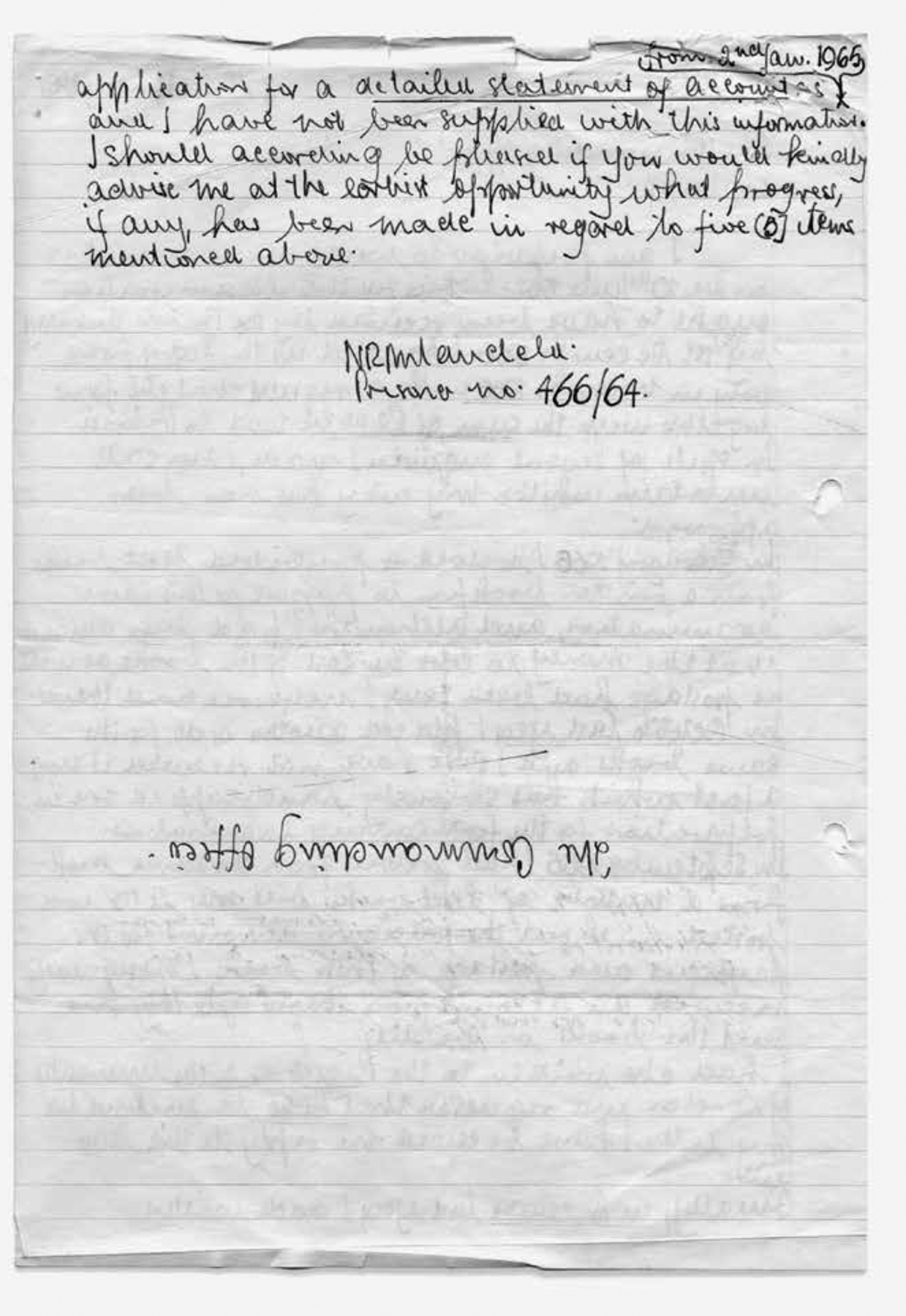

Finally, in December last year, I made written application for a detailed statement of account as from 2nd January 1965 and I have not been supplied with this information. I should according[ly] be pleased if you would kindly advise me at the earliest opportunity what progress, if any, has been made in regard to five (5) items mentioned above.

[Signed NRMandela]

Prisoner no. 466/64

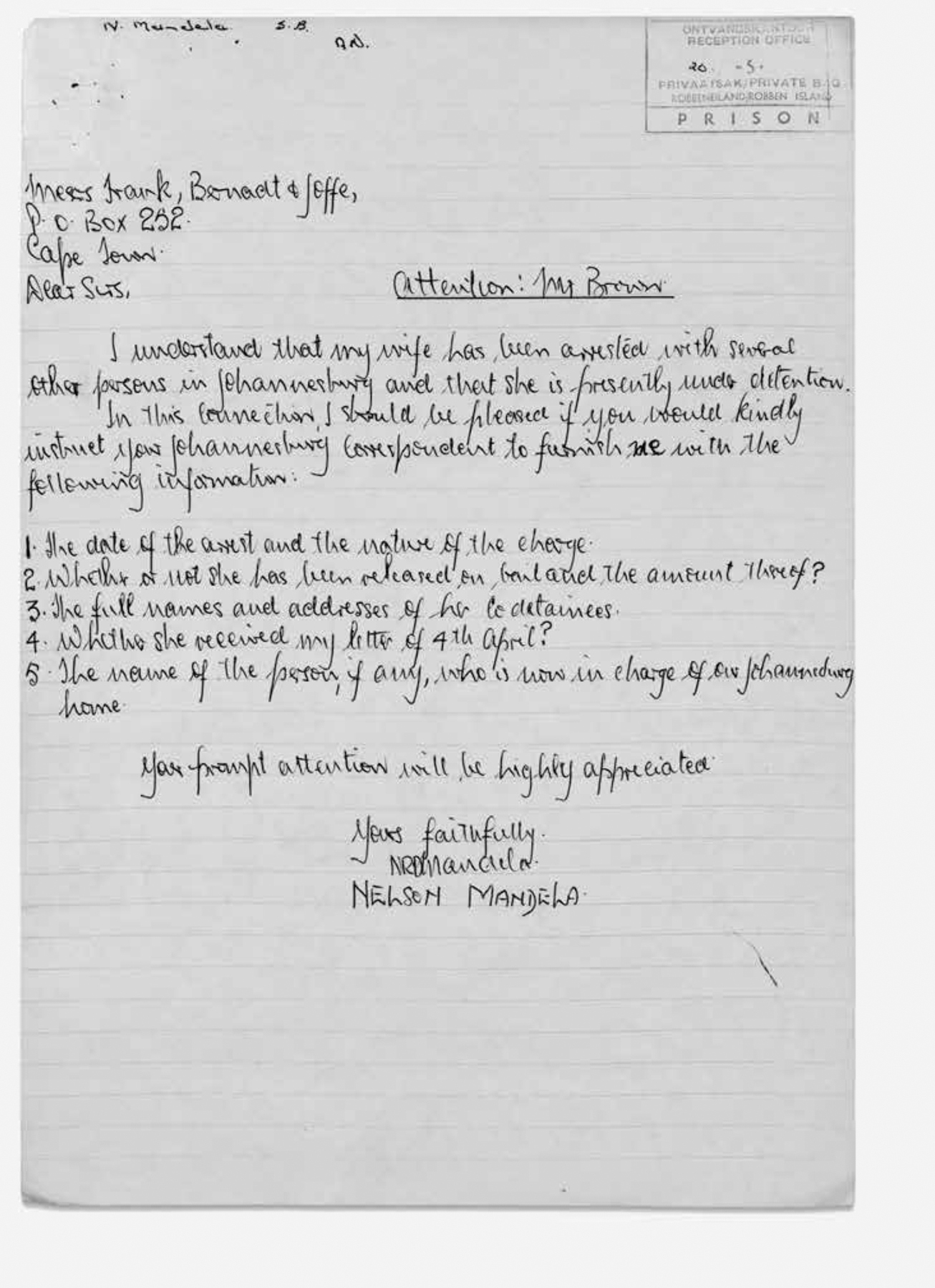

To, Frank, Bernadt & Joffe, his attorneys

Copyi

21st March 1967

Messrs Frank, Bernadt & Joffe

PO Box 252

Cape Town

Attention: Mr Brown

Dear Sirs,

I am charged with being lazy, careless or negligent in my workii and the case has been set down for hearing on the 4th April 1967. In this connection I should be pleased if your Mr Brown would kindly appear for me.

My defence will be that I suffer from high blood pressure for which I have been receiving treatment in this prison since the 14th June 1964 and that, in the circumstances, pick-and-shovel work, which I do at the lime quarry, is strenuous and dangerous to my health.

I propose calling as a witness a Cape Town physician, Dr. Kaplan, who gave me a thorough examination on the 15th April 1966 with the aid of technical instruments. I mentioned this matter to the official who gave me the charge sheet, and pointed out, at the same time, that I did not have the funds to cover the fees of the physician. I asked that the Prison Department should undertake responsibility for payment of these fees. This request was refused and I ask you to consider the possibility of making an urgent application to the Supreme Court for an order directing the Prison Department to pay these charges, if you consider that such an application would have a fair chance of success. The prison doctor, who has throughout treated me with kind consideration, checks my blood pressure regularly and gives me treatment for it as well as for swelling feet, but he will naturally not be in a position to give evidence on the examination by the physician on the 15th April as such evidence would be hearsay.

Finally, having regard to the atmosphere that prevails in this place, details of which will be supplied to you during consultation if necessary, I consider it not compatible with the interests of justice that my trial should be heard by a prison official and I ask that you demand trial by a magistrate.

I will be able to raise the funds to cover your fees.i

Yours faithfully,

[Signed NRMandela] (NELSON MANDELA)

This letter marks the first salvo in what turned out to be a long, drawn-out war with state officials over attempts to have Mandela disbarred as an attorney. In the first attempt the authorities relied on his 1952 conviction under the Suppression of Communism Act,ii a law to outlaw the Communist Party of South Africa from 1950. Its secondary role was to taint all opponents of apartheid as Communists and thereby punish and at least neutralise them. On 2 December 1952 Mandela and nineteen others were convicted for their participation in the 1952 Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws, commonly known as the Defiance Campaign. It was a creation of the ANC and the South African Indian Congress as a popular initiative to highlight six of the laws the National Party created after it won power in 1948 and brought in the policy of apartheid.

Looking back some twenty-five-years later, while in conversation with American writer Richard Stengel, Mandela remembered being defended at no charge by Walter Pollak, then the Chair of the Bar Council. ‘The court dismissed the application of the Law Society on the ground that to be convicted for your political convictions does not make a person who is unfit to be a lawyer.’46

The second attempt turned on his conviction for sabotage, essentially in terms of a certain section of the Internal Security Act. On that occasion, Mandela decided to conduct his own defence and demanded to be let off hard labour to prepare his case. ‘I wanted tables, chairs, proper chairs, proper lighting for me to prepare the case. I also wanted to be taken to Pretoria where the case was going to be heard, so that I could have access to the library.’47

After much correspondence, the case was withdrawn. The prison authorities had refused Mandela’s demand to be let off the back-breaking work in the lime quarry from 7:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. on weekdays, they didn’t want to provide better food to aid his concentration, and they would not transfer him to Pretoria for the duration of the case.

‘Throughout my imprisonment, when I threatened to go to court, they pulled back. They didn’t mind me briefing a lawyer, they didn’t mind me getting a lawyer to argue my case, but when I said I don’t want a lawyer, I want to appear in court myself, they did not want that, and they pulled back,’ he said.

‘Because they were afraid of the publicity?’ Stengel enquired.

‘Yes. They wanted the people to forget about me as much as possible.’48

To Joel Carlson,i his attorney

[Note in another hand] 466/64 Nelson Mandela letter to attorneyii

Mr J Carlson [Stamp dated 1967]

PO Box 8533

Johannesburg

Dear Sir,

On 19th June 1967, about an hour after my interview with you, a member of the security staff handed me a letter, signed by the Liquidator appointed in terms of the Suppression of Communism Act (Act No 44 of 1950),iii drawing my attention to a judgment delivered on 2.12.52 by Justice Rumpff in the Witwatersrand Local Division. In the opinion of the Liquidator the findings and verdict in this case were conclusive of my having contravened Section 11(b) of the above act. Copy of the aforementioned judgment was attached. On the basis of this judgment he proposed to include my name on the list of office-bearers, members or active supporters of the Communist Party of South Africa, and he invites me to make representation within 30 days from the date of the letter (i.e. from 23.5.67).

I am instructing you to handle this matter on my behalf. I would have preferred a personal interview with you. In fact the same day I received the Liquidator’s letter, I wrote to the Commanding Officer and asked him to telephone urgently, and at my expense, to ask you to return to the Island for a consultation on this matter, but permission to communicate with you was granted only yesterday. I cannot give you proper instructions by correspondence and I should be pleased if you would kindly arrange a consultation. I assume that it will not be possible for you to come down and I should, therefore, be pleased if you would kindly instruct your Cape Town correspondent, Mr Brown of Frank, Bernadt & Joffe to see me. I should further be pleased if you would communicate with the Liquidator and advise him that you are now handling the matter.

Yours faithfully,

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA

P.T.O.

The judgment relied upon by the Liquidator is the one where I was convicted with 19 others for the part we played in organising the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws.

[Initialled NRM]

To the liquidator, Department of Justice

[Stamped 23 October 1967 by the Robben Island prison reception office]

The Liquidator

Department of Justice,

Pretoria.

Sir,

Re: Communist Party of South Africa

I have received your letter of the 23rd May 1967 to which you attach copy of a judgement delivered on the 2nd December 1952 by the Honourable Justice Rumpff in the Witwatersrand Local Division of the Supreme Court in which case I was one of twenty accused.

You state that the findings and verdict in that case were in your mind conclusive of my having contravened Section 11 (b) of Act No. 44 of 1950 as charged.i

Finally you advise that I may submit to you further representations in this regard.

At the outset, I wish to reiterate the statement I made in previous correspondence with you that I have never been an officer-bearer, officer, member or active supporter of the Communist Party of South Africa. I further deny that my conviction in the above case entitles you to include my name in the list of persons who were members or active supporters of the Communist Party and I will strenuously contest any efforts on your part to do so. It is my firm belief that the allegation that I was a member or active supporter of the Communist Party is an act of persecution and a propaganda manoeuvre intended to distort my political beliefs and to justify the removal of my name from the roll of attorneys. It is not in any way inspired by any honest belief that I am a Communist. A study of the correspondence in this matter confirms my view.

In your letter of the 1st July 1966, you advised me that the Minister of Justice had in terms of subsection (10) of section 4 of Act No 44 of 1950 directed you to complete a list of persons who were or had at any time before or after the commencement of the said Act been office-bearers, officers, members or active supporters of the Communist party which was by subsection (1) of section 2 of the said Act declared to be an unlawful organisation. In that letter you further advised me that evidence had been placed before you that I had been a member and active supporter of the said Communist Party. You then afforded me opportunity, in terms of section 4, to show why my name should not be included in the abovementioned list.

In my letter of the 15th July 1966, I emphatically denied that I was a member of the Communist Party. I pointed out that since you had given me no particulars in regard to this allegation, I could do no more at that stage than merely to make a bare denial. I accordingly asked you to furnish me with full particulars of such evidence as had been placed before you. Your reply of the 27th July 1966 stated expressly that sworn evidence had been placed before you to show that I had been a member [of] the Communist Party since 1960 and that I had taken part in its activities, inter alia, by attending conferences of the said Party. On the . . . [sic] August I wrote and asked you to furnish me with detailed particulars. After a silence of almost four months, I received your letter of the 15th December 1966 in which you informed me that it had been decided not to include my name in the list of office-bearers, officers, members or active supporters of the Communist Party at that stage. No reference whatsoever was made to my letter of the . . . [sic] August 1966 and the particulars I had asked for.

Five months thereafter you wrote me your letter of the 23rd May 1967 and confronted me with a completely new allegation. Now it was proposed listing me because of my conviction in December 1952 for contravening section 11(b) of the above Act. The original allegation that I was a member of the Communist Party since 1960 was abandoned and I was deprived of the opportunity of clearing my name by publicly demonstrating its falsity. Now it was maintained by inference, that I had been such a member since 1952. If it is seriously contended that the 1952 judgement made me a member or active supporter of the Communist Party, why then was it necessary first to proceed against me on the ground that I had been a member since 1960?

It is my contention that the first allegation was abandoned simply because it was from the beginning untrue and because the particulars I asked for could not be supplied. I contend further that the fact that it has taken fifteen years before proceedings were started to list me suggests that throughout this period, the above conviction was not considered to have put me in the category of persons who were members or active supporters of the Communist Party. I feel obliged to point out that the proposal to include my name in the said list is an act of victimisation and has nothing whatsoever to do with the fulfilment of duties imposed by section 4 of the above Act.

As more fully appears from the copy of the judgement attached to your letter of the 23rd May 1967, I and nineteen others were sentenced for the part we played in organising the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws. The Campaign was organised and directed by a National Action Council which was composed of representatives of the African National Congress and the South African Indian Congress, and was based on the principles of non-violence which were adopted by Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru in India. It was a protest against certain selected apartheid legislation which we considered harsh and unjust. The actual demonstrations were peaceful and disciplined and it was because of this consideration that the Learned Judge decided to suspend sentence [sic]. The Campaign had nothing whatsoever to do with Communism. Its object was to secure a redress of the just and legitimate grievances of the African, Indian and Coloured people of this country.

To the best of my knowledge and belief, of the twenty accused in the above case, ten had already been listed under the above Act when they were convicted on the 2nd December 1952, all of them having been members of the Communist Party before it was dissolved in 1950. Of the remaining ten, with the exception of myself, I am not aware of any proceedings that have been taken to list any one of them because of the above conviction. I have been singled out and treated differently from my co-accused in that case, some of whom held, at the time, more senior positions in the political organisations than I did. The only inference I can draw from this differential treatment is that in my case the above conviction is considered to have made me a member or active supporter of the Communist Party, whereas the same conviction carries no such implications as far as the rest of the accused were concerned.

Even in my case for fifteen years after the conviction, it was apparently not deemed necessary to put my name on the list. Only now that I am a prisoner serving a life sentence was it considered expedient to do so. I am forced to the conclusion that in making the original allegation advantage was being taken of my disabilities as an incarcerated person and it was apparently thought that I would consequently be unable to contest the allegation. It is my considered opinion that resort is now being made to the 1952 conviction for the purpose of saving face.

In any event the Communist party was dissolved in 1950 shortly before Act no 44 of 1950 was promulgated and was re-formed only in 1953. This information was given to me by Messrs Govan Mbeki,i Raymond Mhlabaii and Elias Motsoalediiii all of whom are prisoners serving life sentences in Robben Island. Mr Mhlaba informs me that up to June 1950 when the Communist Party was dissolved at a Conference held in Cape Town, he was secretary of the Port Elizabeth District of that body, and that he attended the dissolution conference. Mr Motsoaledi, who was at that time Group’s Secretary in Johannesburg, confirmed Mr Mhlaba’s statement. Mr Mbeki who, prior to his arrest in July 1963, was a member of the Port Elizabeth District Committee, informs me that a new Communist Party was formed in 1953 and bore the name South African Communist Party. There was thus no Communist Party between June 1950 and 1953. I could, therefore, not be a member or active supporter of an organisation that did not exist. I accordingly submit that the above conviction does not entitle you to include my name in the list of persons who were members or active supporters of the Communist Party.

The case of R V Adams 1959 (1) S.A. 646 (Special Court), which is popularly referred to as the Treason Trial,iv and in which I was one of the accused, is relevant. The Crown, as it then was, alleged a conspiracy to overthrow the existing state by violence and to replace it with a Communist state. The indictment, as far as I can remember, covered the period of 1st December 1952 to December 1956, and included a count under Act no 44 of 1950. Amongst the bodies that were involved in this case were the African National Congress and the South African Indian Congress, the same organisations that organised the Defiance Campaigni in 1952. I was one of the witnesses that were called for the defence, and who were cross-examined by counsel for the Crown. The verdict was given on the 29th March 1961 when all the accused were acquitted. The reasons for judgement were handed in about a month thereafter. I never saw any report, official or otherwise, of the reasons for the judgement. But I read press reports according to which it appeared that the same Justice Rumpff who convicted me on the 2nd December 1952, and on whose judgement you now rely, made observations which seemed to indicate that he did not consider me to be a Communist. If this be correct, then I contend that such a finding would be conclusive of the fact that I was not, during the period covered by the indictment, a member or active supporter of the Communist Party.

As far as the question of my political beliefs is concerned, I have always regarded myself, first and foremost, as a nationalist, and I have throughout my political career been influenced by the ideology of African nationalism. My one ambition in life is, and has always been, to play my role in the struggle of my people against oppression and exploitation by whites. I fight for the right of the African people to rule themselves in their own country.

Although I am a nationalist, I am by no means a racialist. I fully accept that principle stated in the report of the Joint Planning Council of the African National Congress and the South African Indian Congress which is quoted on page 5 of the judgement attached to your letter of the 23rd May 1967 that all people irrespective of the national group they may belong to, are entitled to live a full and free life on the basis of the fullest equality.

I have read Marxist literature and I am impressed by the idea of a classless society. I am firmly convinced that only socialism can do away with the poverty, disease and illiteracy that are prevalent amongst my people, and that maximum industrial development is the result of central planning and the nationalisation of the key industries of the country. But I am not a Marxist. As far as South Africa is concerned, I believe that the most immediate task facing the oppressed people today is not the introduction of a workers’ government and the building of Communist society. The principal task before us is the overthrow of white supremacy in all its ramifications, and the establishment of a democratic government in which all South Africans, irrespective of their station in life, of their colour or political beliefs will live side by side in perfect harmony.

The one organisation which appeared to me best suited to undertake the task of uniting the African people, and that would eventually win back our freedom, was the African National Congress. I joined it in 1944 and in 1952 I became its Transvaal president and Deputy National President. In 1953 I was served with a notice in terms of the above Act calling upon me to resign from the African National Congress and never again to take part in its activities. It was formed in 1912 to strive for the liberation of the African people. Throughout its history it was inspired by the idea of African nationalism. In 1956 it adopted the Freedom Charteri a policy document which embodies the principles upon which the African National Congress will build a new South Africa. At the Treason Trial the Crown alleged that the Charter was a blue-print for a Communist state and called expert evidence to substantiate the allegation. On the other hand, the defence contended that the Charter was not a Communist document, but that its terms embodied the demands of a movement of national liberation. Amongst the evidence led by the defence to refute the allegation made by the prosecution was an article which I had written in the monthly magazine Liberation of June 1956 in which I posed precisely this same question, namely, whether the Charter was a blue-print for a Communist state.ii In that article, I had endeavoured to show that, apart from the clauses dealing with the nationalisation of mines, banks and other monopolies, the Charter was based on the principle of free enterprise, and that when its terms were implemented, capitalism amongst Africans would flourish as never before. In the press reports referred to above, Mr Justice Rumpff was reported to have expressly referred to this article and relied partly on it in holding that the Crown had not proved the allegation that the Charter was a Communist document. The African National Congress is a nationalist, and not a Marxist organisation, and, unlike the Communist Party whose membership is open to all national groups, it is an organisation exclusively for Africans.iii

Although it is not a Marxist organisation, the African National Congress had often co-operated with the Communist Party on matters of common concern. Such cooperation became possible because the Communist Party supported the liberation struggle of the African people. Instances of such cooperation between national movements and Marxist parties are to be found all over the world. For example, in the struggle for national independence in India, the All-India National Congress Cooperated with the Communist Party of India.

Communists have always been free to join the African National Congress and many of them are members, and some of them even serve on its national, provincial and local committees. Inside the African National Congress, and in my political work generally, I have worked closely with Communists, especially Messrs Moses Kotane,i J.B. Marksii and Dan Tloome.iii It is easy to understand why Communists are admitted as members of the African National Congress when one takes into account the fact that this organisation is not a political party but a political organisation in which various shades of opinion are permitted. It is a parliament of the African people. Just as there are Communist Parliamentarians in France, Italy and other western countries, so do we find Communists in the membership of the African National Congress. But the cooperation referred to between the Communists mentioned above and me has been limited to such matters as I considered to be within the framework of the policy of the African National Congress or as furthered the general struggle against racial oppression. But in no way have Communists, either as an organisation or as individuals, exercised any control over my political beliefs or activities nor did I, at any time, support their objects or programme.

Before I was banned in 1953, I had also taken part in the activities of the South African Peace Council,iv of which I was one of the vice-Presidents. The Reverend D.C Thompson was at the time, its national chairman and its object was the preservation of world peace. It ran specific campaigns centering around the question; as for example the campaign to induce the Five Big Powers to conclude a Pact of Peace. It was not a Communist movement but Communists like Messrs A. Fischer,v A.M. Kathrada, and Miss Hilda Watts,vi served on its committees! In 1953 the Minister of Justice ordered me to resign from the Council.

In March 1961 I was the main speaker at an All-in African Conference which was held at Pietermaritzburg. The Conference had been called to protest against the decision of the Government to establish a Republic without consulting Africans. The Conference was attended by Africans from various walks of life – sportsmen, churchmen and politicians. A resolution was adopted demanding that the Government call a national Convention of all South Africans, black and white, to draw up a new democratic constitution for the country. The resolution called for mass demonstrations on the 29th, 30th and 31st May 1961 if the Government failed to summon the Convention. I was the Honorary Secretary of the Conference and took the lead in organising the general strike on the eve of the declaration of the Republic. A year later I was convicted and sentenced to three years imprisonment for organising this strike, and I have been in jail ever since. There was nothing in the Conference that was Communistic nor could it be argued that the above resolution advocated an object of Communism.

I played a leading role in the formation of Umkhonto weSizwe in November 1961 which planned and directed the acts of sabotage in this country. The formation of Umkhonto was the direct result of the policy of the Government to rule the country by force, a policy which made all forms of constitutional struggle impossible. The Communist Party was represented on the National High Command, the governing body of Umkhonto. But its representatives formed a minority and did not in any way direct its policy.

Early in January 1962 I left the country to attend the conference of the Pan-African Freedom Movement for Central, East and Southern Africa which was to be held in Addis Ababa in February that year. This was a conference of African nationalists called for the purpose of examining problems and of formulating plans for the liberation of the oppressed people in the Pafmecsai area. After the conference I toured Africa and visited England. I did not visit any of the Communist countries. In 1962 I was convicted and sentenced to two years imprisonment for leaving the country without a passport.

A study of my political background demonstrates that I have never been a member or active supporter of the Communist Party of South Africa or of its successor, the South African Communist Party. On the contrary, that background shows that I am a nationalist. One ambition has dominated my thinking, my political beliefs and my political actions. This is the idea of exploding the myth of white supremacy and of winning back our country. The only body which has enabled our people to forge ahead in our freedom struggle in the past, and which will lead us to our final goal in the future is, and has always been, the African National Congress with its dynamic creed of African nationalism. All my efforts to help advance the struggle of my people have been made through the African National Congress. If on occasions I served on other bodies it was because I considered that those bodies and their work helped to speed the liberation of the African people.

Finally, I deny that my conviction of the 2nd December 1952 entitles you to include my name in the list of persons who were members or active supporters of the Communist Party.

Yours faithfully

[Signed NRMandela]

N.R. Mandela

To the registrar of the Supreme Court

[Typed]

Private Bag,

ROBBEN ISLAND.

CAPE PROVINCE.

6th December 1967.

The Registrar of the Supreme Court,

PRETORIA

Dear Sir,

Re: SECRETARY FOR JUSTICE vs NELSON ROLIHLAHLA MANDELA: APPLICATION FOR REMOVAL FROM THE ROLL OF ATTORNEYS. M 1529/1967

I have to advise that I am opposing the above application and it is my intention to attend the hearing in order to submit my argument in person. Formal notice of opposition will be filed in due course.

As indicated in paragraph 2 of [the] applicant’s affidavit, I am at present serving a sentence of life imprisonment at Robben Island. The material that I require for [the] purpose of preparing the answering Affidavit and argument is located in the Transvaal Province, and it will be impossible for me to prepare the case from Robben Island.

It will be equally impossible for me to attend the hearing unless the prison authorities make the necessary arrangements for me to do so. I have accordingly written to the Commissioner of Prisons today requesting him to transfer me immediately to Pretoria for purposes of preparing the said Affidavit. I have further requested the Commissioner to make arrangements to enable me to attend the hearing.

In this connection I enclose copies of letters written to [the] applicant’s Attorney and to the Commissioner respectivelyi so that the court may be aware of my difficulties in this matter, I particularly wish to draw attention to the letter addressed to [the] applicant’s Attorney in which I ask for an extension of the time within which I should file the Affidavit.

Should [the] Applicant’s Attorney refuse my request I shall have no alternative but to apply to court for such an extension.ii

Yours faithfully,

[Signed Nelson R. Mandela]

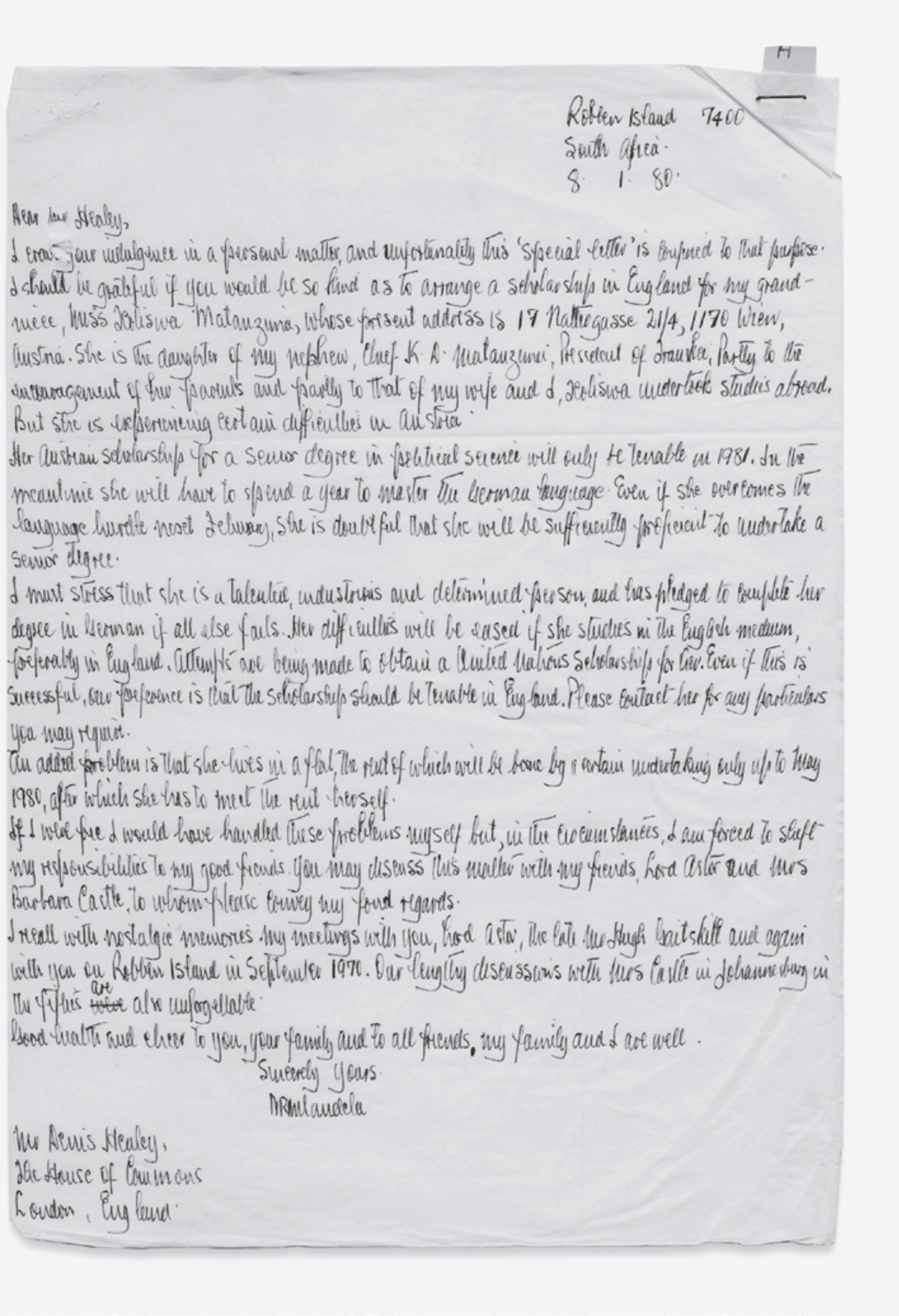

It is clear from correspondence in Mandela’s prison files held by the National Archives and Records Service of South Africa, that he wrote on several occasions to Adelaide Tambo, the wife of his former law partner and the president of the ANC, Oliver Tambo, who was living in exile with his family in London, and running the organisation from abroad. It is unlikely that Adelaide Tambo received the letters before the latter part of his prison sentence. In 1968 Mandela wrote to her care of his wife and used her African name, Matlala, and the surname Mandela. A note in Afrikaans at the end of one of the letters shows that the prison authorities had worked out the identity of the real recipient because someone has written ‘A Tambo’ on the letter. Just this information would have been enough for them to hold it back. It is highly probable that all the underlined text in this letter is the work of the prison censors, drawing attention to individuals that are known to them or whom they want to identify.

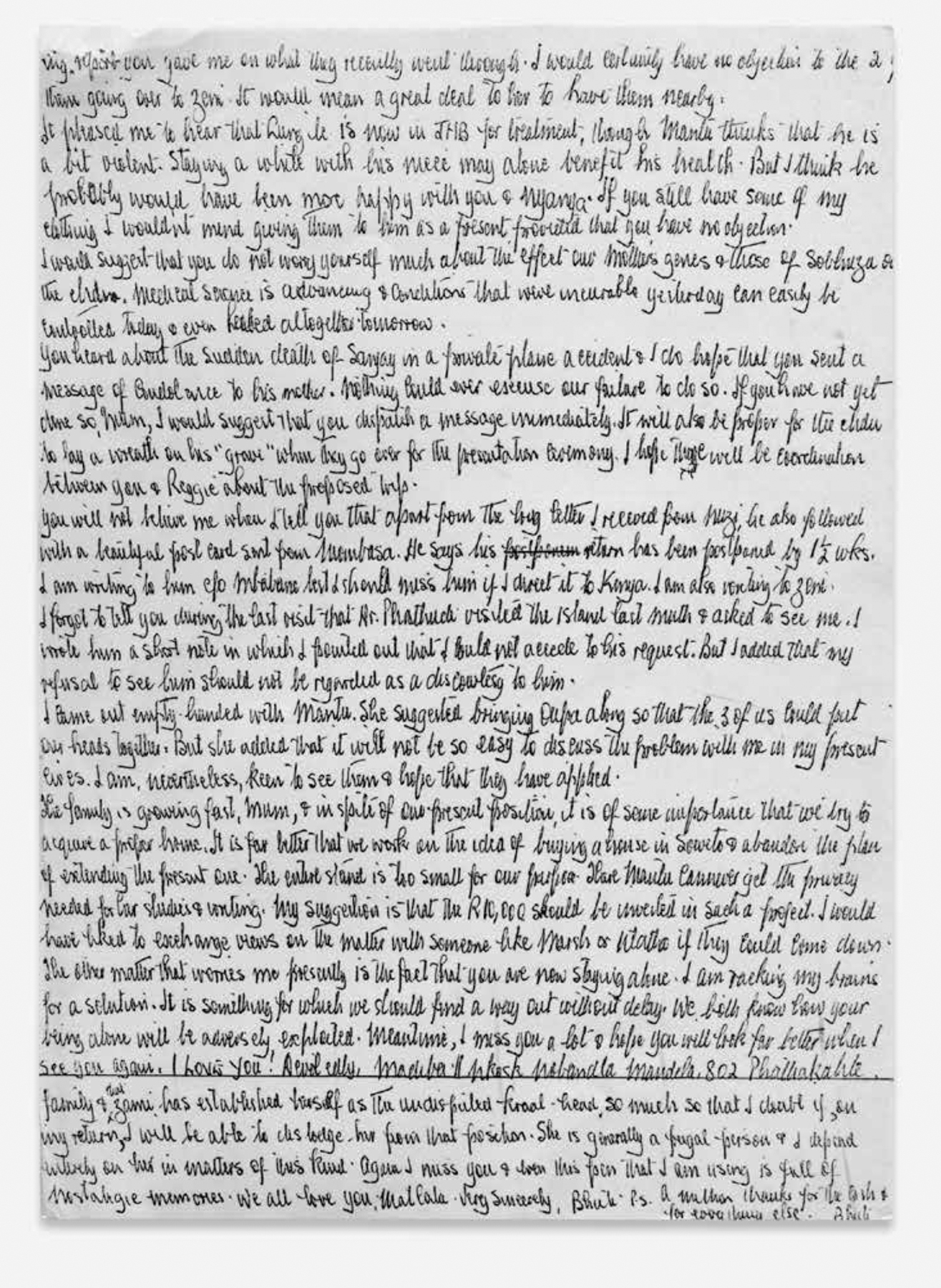

To Adelaide Tambo,i friend, anti-apartheid activist, and the wife of Oliver Tambo, ANC president and Mandela’s former law partnerii

5.3.68

[Note in another hand says ‘My sister’.]

Kgaitsedi yaka,iii

I send you my warmest love. You, Reginald,iv Thembi, and Dalindlelav the baby have been in my thoughts during the past five years, and it gives me great pleasure to be able to tell you this.

I hope you have all been keeping well. Zamivi gives me scraps of information about you in her letters and whenever she comes down, but the last occasion I heard from you directly was when I received Reggie’svii inciting telegram during my first case. I was tremendously inspired. It arrived almost simultaneously with that from the late Chief, and both messages gave a new dimension to the issues.

News of the widespread efforts made by our householdviii during the first half of ’64 played a similar role. Such efforts fortified our spirits and relieved the grimness of that period.

But I must return to you Matlala.ix Just exactly where do I start? Certainly not from the day in the early fifties when Reggie and I drove to the Helping Handx where you presented him with a smart jersey that you had especially knitted for the occasion. That would take us far back. Suffice to say that I thought you played your cards very well. Nor do I wish to remind you [of] the pertinent observations you used to make during the numerous consultations we attended together with the late Rita, Effiexi and others on matters that vitally affected the interests of your profession,xii the savoury meals I enjoyed when I visited you in the East shortly after your wedding as well as in June ’62 over there.xiii The correspondence we had in ’61 was stimulating and was widely discussed among us at the time. These and numerous other incidents have flashed across my mind on many occasions and I love to recall them.

I was sorry to learn that you had abandoned your studies.i In July ’62 I had mentioned the matter to Xamelaii and others, and the news of which they approved fully, had much excited them. In fact we were calculating only the other day that you had either completed or [were] at least doing the final year. Anyway I am sure you and Reggie must have weighed the matter very carefully and, there must have been a good reason for terminating the studies.

Thembi, Dali and the babyiii must have grown and I would love to hear about them. Please give them my love. I hope Thembi still remembers the Saturday morning when you and herself visited Chancellor House.iv In the general office and with all the clients around I complimented her on her new dress, whereupon she promptly [displayed] the dress, boasting that “i ne stiffening” to the amusement of everybody there.

I also think of Malume and the heavyweight from the western areasv and hope that they still find time to dye their hair. Incidentally, during our sojourn with Reggie, I remarked that he was beginning to turn grey and drew from him the grave comment: “Please don’t tell me that, don’t tell me that”. I am sure my good friend Gcwanini,vi always polite and peaceful for the [first] five days of the week and who always allowed himself relaxation from these virtues and a bit of rioting on weekends still will remember the night we spent at home together with Peter. Then there is the nocturnal Ngwali, who never got tired of waking us up at midnight to burden us with numerous problems, and the ubiquitous Bakwe.vii I believe problems of weight have slowed down the activities of both. Madiba of Orlando East, the two Gambus, Alfred, Mzwayi, Tom, Dinou, Maindy,viii and Gabula, I remember them all. I hope you still see Tough Guy and Hazel. Has he produced anything new after “The Road to . . .?” Any new literature from Todd and Esme,i or musical composition? Do you hear of Cousin, Mlahleni, and Mpumi?ii I would like to be remembered to all of them.

Our family has always attached a great deal of importance to education and progress, and the widespread illiteracy facing us has always been a matter of grave concern. Efforts to overcome this problem have always been frustrated by lack of funds and of adequate facilities for academic and vocational training. Now these problems are being gradually tackled and solved and increasing numbers of school-going youths are finding their way into boarding schools and technical colleges. It flatters one’s pride to know that those who have completed their courses and who have been given posts and assignments are doing so exceptionally well. Heartiest congratulations and fondest regards to all.

The pronoun “I” has been prominent in this correspondence. I would have preferred “we”. But I am constrained to use terminology acceptable to the practice of this establishment, however much it may be incompatible with my own individual [taste]. I am sure you will pardon me for the egotism.

Once again, I wish you to know that you, Reggie, the kids and all my friends are constantly in my thoughts. I know you must be worried about my incarceration. But let me assure you that I am well, fit and on top of the world, and nothing would please me more than to hear from you.

In the meantime my warmest to you and fondest regards to all.

Sincerely,

Nel

[Written in another hand in Afrikaans] (Contents from inside the envelope).

[Envelope]

Miss Matlala Mandela,iii

8155, Orlando West,

Johannesburg.

To the commanding officer, Robben Island

29th April 1968

The Commanding Officer,

Robben Island

Attention: Capt. Naude

As more fully appears from the accompanying letter to the Cultural Attaché, British Embassy, Pretoria, I have decided to withdraw my name from the list of candidates this year. I might add that in terms of the Regulations of the University of London I am expected to write Part II within two years after completing Part I which I did only in 1967. I had, however, planned to attempt it within one year of completing Part I. In view of the late arrival of the study books, however, I have elected to postpone the examination until June 1969.

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA 466/64

To the cultural attaché, British Embassy

[In Mandela’s hand] Copy

29th April 1968

The Cultural Attaché,

The British Embassy,

Pretoria.

Attention: Mrs S Goodspeed

Dear Sir,

I will not be able to sit for the University of London LL.B Examination Part II of the Final year. On the 25th January 1968 I placed an order with the London book firm of Messrs Sweet & Maxwell, Spon, Limited for certain law books which I needed for purposes of preparations for the above Examinations. These books were only delivered to me on the 23rd April 1968 and I now consider it unwise to tackle the examination.

I propose presenting myself in June 1969 and I should be pleased if you would kindly withdraw my name from this year’s examination list.

Yours faithfully,

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA

To the commanding officer, Robben Island

16th September 1968

The Commanding Officer

Robben Island

Attention: Major Kellerman

I should be pleased if you would grant me leave to write to Brigadier Aucampi in connection with the under-mentioned matter.

I intend applying to the Registrar of the University of South Africa for permission to postpone the examinations in Afrikaans Course I from the 15th October next to February 1969 on the grounds of ill-health. In terms of the University Regulations such application must be accompanied by a medical certificate specifying the nature of the illness. The Prison Doctor is willing to issue the certificateii but the hospital orderly, H/W Embiekiii, drew his attention to the fact that such a certificate can only be issued with the approval of Capt Naude. A few days thereafter, H/W Embiek informed me that Capt Naude had told him that it was not necessary for me to produce a medical certificate to postpone the forthcoming examination. On the 30th August 1968, and in pursuance of the information given me by the aforesaid head warder, I wrote and requested Capt Naude to authorise the issue of the certificate. On the 9th September Capt Naude informed me that the issue of a medical certificate was a matter entirely in the hands of the doctor and had nothing to do with him – a statement which flatly contradicted that of head warder Embiek. On the same day I consulted the doctor and acquainted him with Capt Naude’s attitude and he promised to go into the matter. Subsequently, the head warder told me he would discuss the matter with Capt Naude. I have heard nothing since.

On the 4th September I had discussed the matter with Brigadier Aucamp who adopted a reasonable and helpful attitude, pointing out in the course of the conversation that he had dealt with such applications in Pretoria, and promised to take up the matter with the Captain. I must assume that, due to pressure of business, he forgot to discuss it, and I should accordingly be pleased if you would grant me leave to place the whole matter before him again.

[Signed NRMandela]

NELSON MANDELA: 466/64

Attention: Major Kellerman

The Commanding Officer,

Robben Island

[Notes in Afrikaans from prison officials]

Major,

For your information [Signed] 16/9/68

Lt. Good. He can write to Brig. Aucamp. It must be sent unofficially.

[Signed] 17/9/68

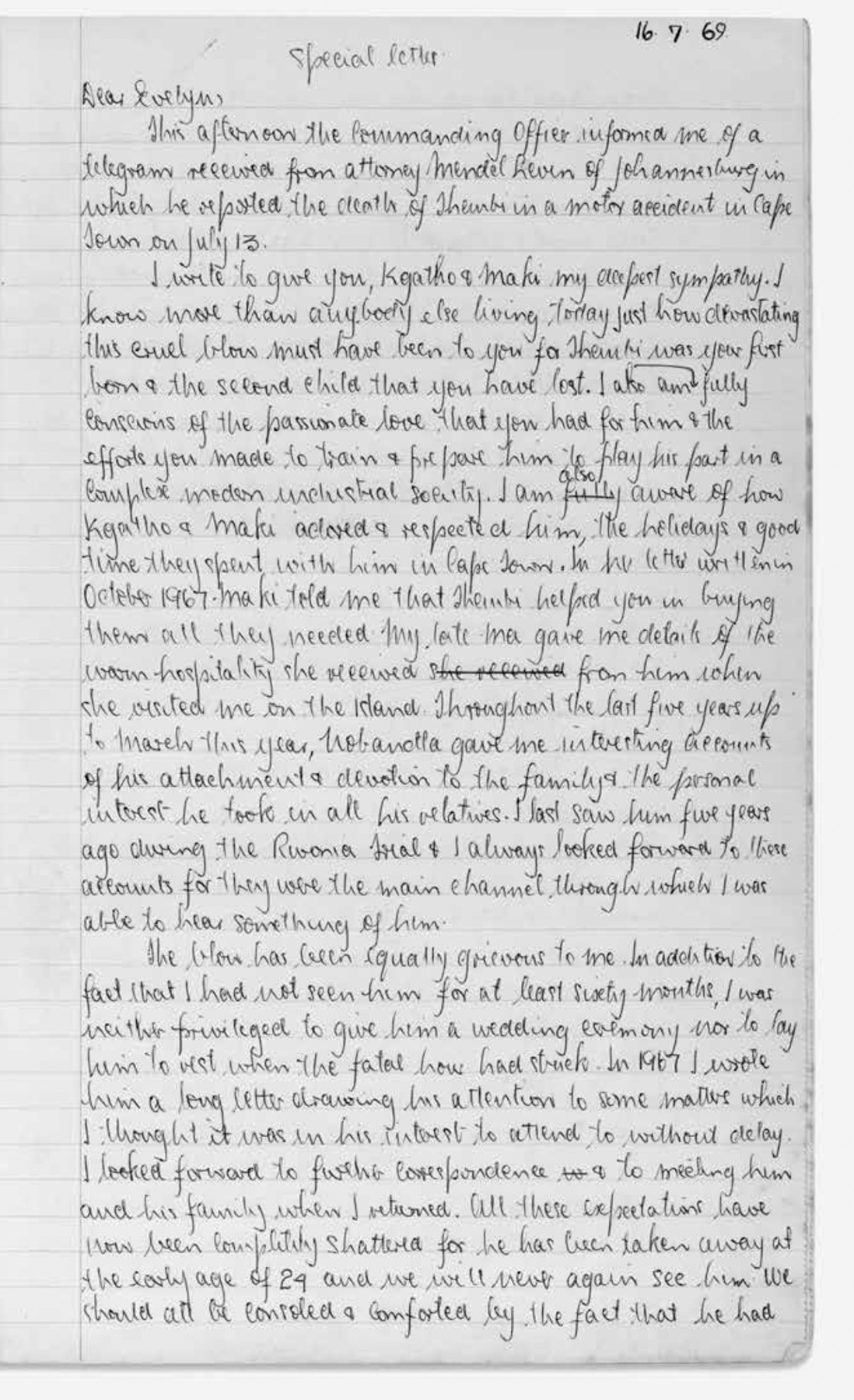

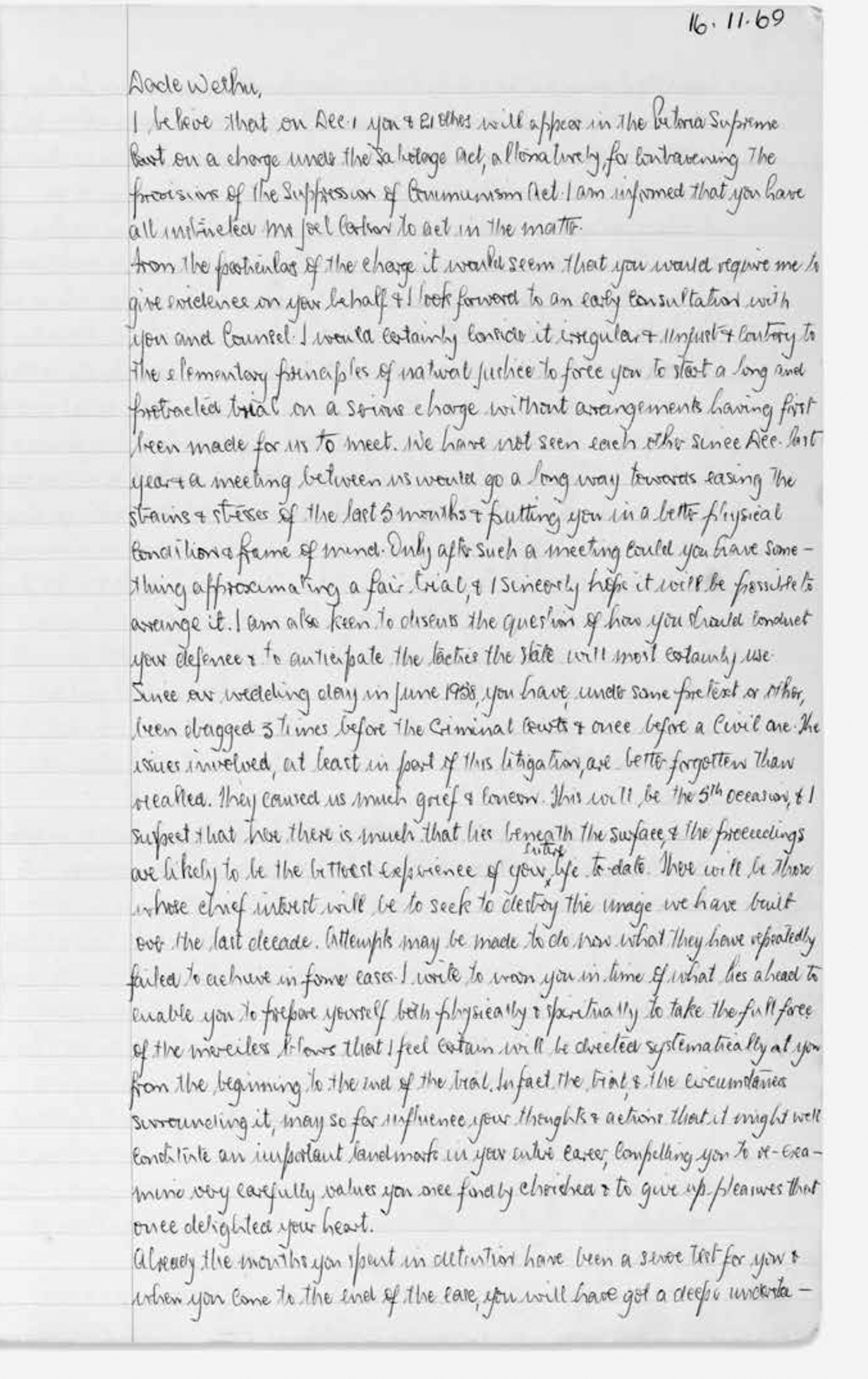

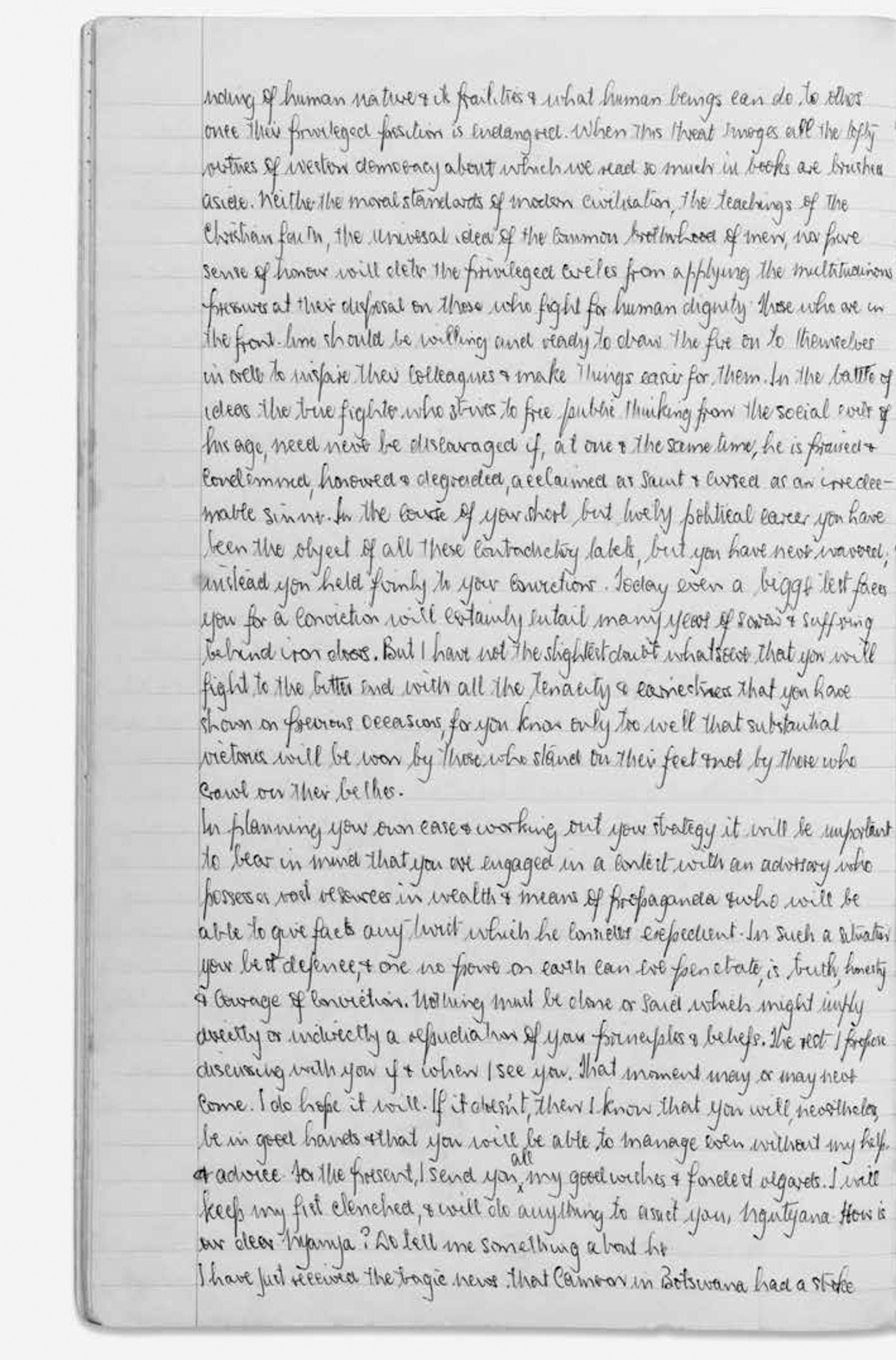

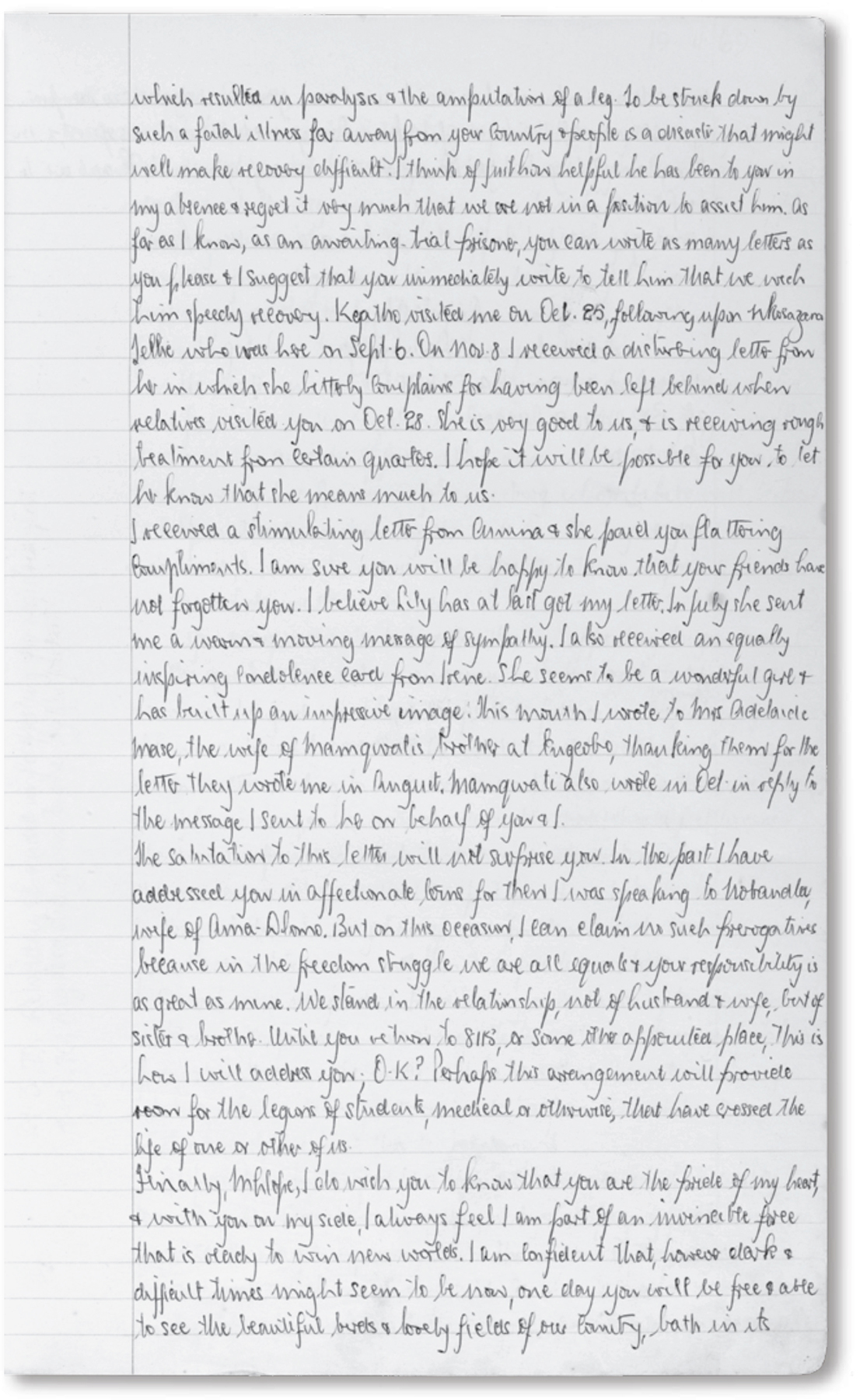

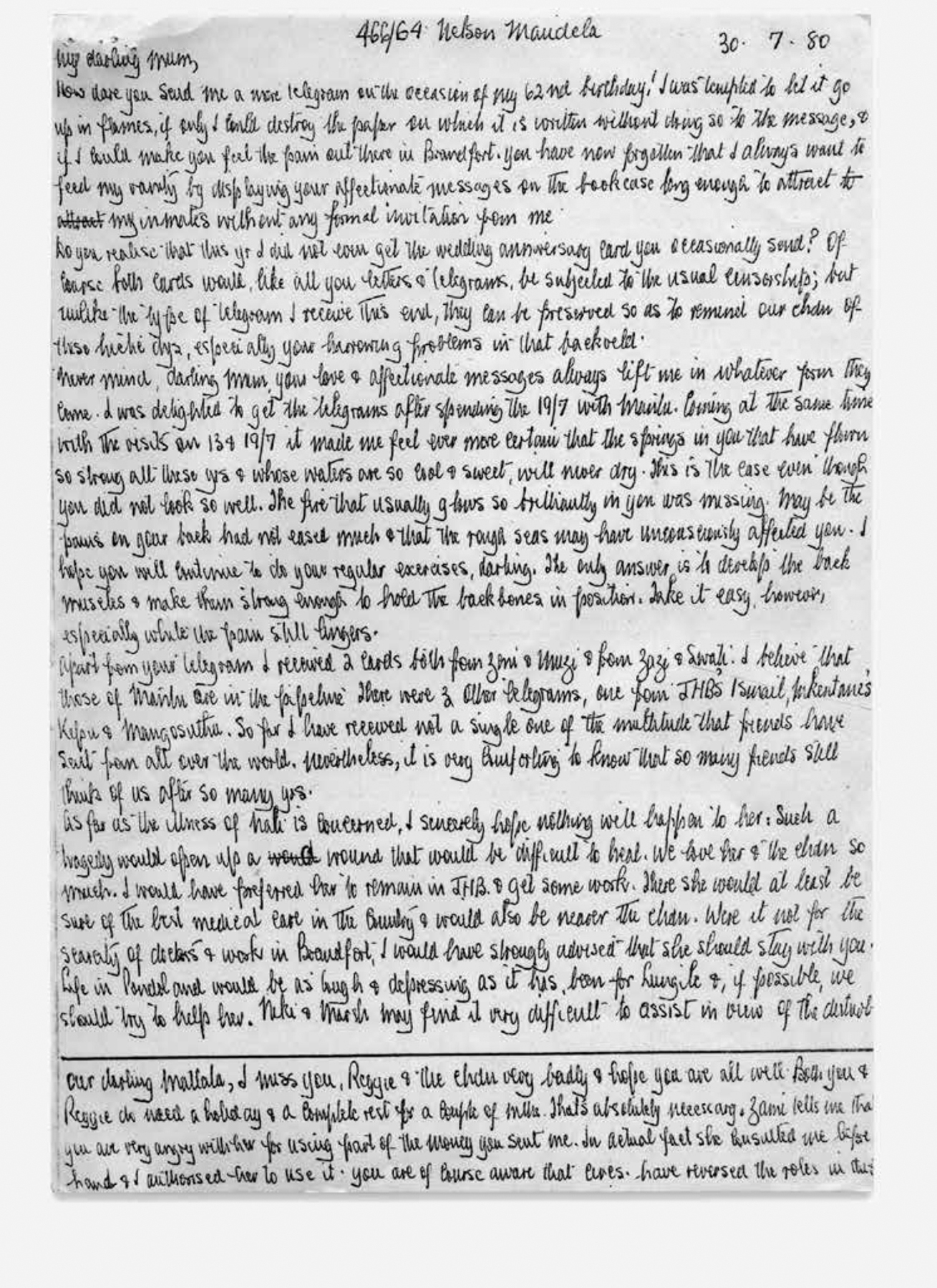

For Nelson Mandela, 1968 marked the beginning of the most harrowing of his years in prison. On 26 September his mother, Nosekeni, died and he was forbidden from attending her funeral. Despite a measured and rational written request to the authorities promising to return to prison after the funeral, he was denied the possibility. He was restricted to writing to those who had attended the funerals offering his deep relief and gratitude.

To K. D. Matanzima,i his nephew, a Thembu chief, and chief minister for the Transkei

[in another hand]: 466/64 Nelson Mandela

[Stamp dated Reception Office Robben Island 14.10.1968]

WHEN ACKNOWLEDGING RECEIPT HEREOF, PLEASE WRITE THE FOLLOWING WORDS AT THE TOP OF YOUR LETTER: “REPLY TO SPECIAL LETTER”.

Nyana Othandekayo,ii

My brother-in-law, Timonthy Mbuzo, visited me two days ago and reported that you attended my mother’s funeral. Your presence at the graveside, in spite of your many preoccupations, means a lot to me, and I should like you to know that I deeply appreciate it.

I last saw my mother on September 9 last year. After the interview I was able to look at her as she walked away towards the boat that would take her to the mainland, and somehow the idea crossed my mind that I would never again set my eyes on her. Her visits had always excited me and the news of her death hit me hard. I at once felt lonely and empty. But my friends here, whose sympathy and affection have always been a source of strength to me, helped to relieve my grief and to raise my spirits. The report on the funeral reinforced my courage. It was a pleasure for me to be informed that my relatives and friends had turned up in large numbers to honour the occasion with their presence and was happy to be able to count you amongst those who paid their last respects to her. Nangomso!iii

In this connection I consider it proper to let you know that I have been kept fully informed of your continued interest in my affairs and those of the family over the last six years. During one of her visits my mother told me that twice you travelled all the way to Qunu to advise her of my conviction. Your visits to [my] Johannesburg home and other acts of hospitality towards the family have all been repeatedly reported by Nobandla.iv This interest stems not only from our close relationship, but also from the long and deep friendship that we have cultivated since our student days kuwe la kwa Rarabe.v

I have written to your brother and Head of the Xumbu Royal House, Jonguhlanga,i to thank him for undertaking the strenuous task of organising and planning the funeral and for the heavy disbursments that he personally made on this occasion in spite of his declining health and [?] commitments. His painstaking concern and care for my mother’s welfare during the past six years and his touching devotion generally have created a profound impression on me and I owe him an immense debt. I only hope his health will improve.

I am also writing to Mr Guzana.ii

This is a special letter allowed me only for the purpose of thanking you for attending the funeral and it is not possible to discuss other matters. I need only request you to give my love to Amakhosikazi Nozuko, Nobandla, No-Gate,iii and to Mthetho,iv Camagwiniv and Wanda; and my fondest regards to Chief Mzimvubu,vi Thembekile, Dalubuhle’s heir, Manzezulu, Gwebindlala and Siyabalala; and to Bros Wonga, Thembekile, Headman Mfebe and Mr Sihle.

I would have much liked to write to my father-in-law and to Mavii and thank them directly for their own share on this occasion, but it will not be possible to do this, and I must accordingly ask you to do so on my behalf.

Yours very sincerely,

Dalibunga.

Chief K.D. Matanzima

Chief Minister for the Transkei

Umtataviii

To Knowledge Guzana,i attorney and leader of the Transkei homeland’s Democratic Partyii

[Stamp dated 14.10.1968]

WHEN ACKNOWLEDGING RECEIPT HEREOF PLEASE WRITE THE FOLLOWING WORDS AT THE TOP OF YOUR LETTER: “REPLY TO SPECIAL LETTER.”

Dear Dambisa,iii

Two days ago my brother-in-law, Timothy Mbuzo,iv informed me that you attended my mother’s funeral and I should like to thank you for this considerate gesture.

Only a keen sense of public duty would enable a man in your position, and on whom there must be heavy and pressing demands for his services, to find time to devote himself to the public good, and I should like you to know that I am greatly indebted to you.

It was never easy for one anywhere to lose a beloved mother. Behind bars such misfortune can be a shattering disaster. This could easily have been the case with me when I was confronted with these tragic news on September 26, which ironically enough was my wife’s birthday. Fortunately for me, however, my friends here, who are endowed with virtues far in excess of anything I can hope to command, are remarkable for their ability to think and feel for others. I have always leaned heavily on their comradeship and solidarity. Their offers of goodwill and encouragement enabled me to face this tragic loss with resignation.

Sibaliv Mkhuze told me that my relatives and friends responded admirably and rallied to the graveside. This was a magnificent demonstration of solidarity which gave me a shot in the arm, and it is a source of tremendous inspiration for me to count you amongst those who gave me this encouragement.

I have also written to your friend and head of the Tembuvi Royal House,vii Jonguhlanga, to thank him for undertaking the strenuous task of planning the funeral, and this in spite of his declining health and heavy commitments. His touching devotion to his relatives, friends and people generally has created a profound impression far and wide. I only hope that his health might improve.

This is a special letter allowed me only for the purpose of thanking you for attending the funeral and it is not possible to refer to wider issues. It is sufficient for me to say that I am happy to note that the interest you showed in public affairs as a student at S.A.N.Ci 30 years ago has not flagged. I hope that in this note I have succeeded in placing on record not only my deep gratitude to you for honouring the occasion with your presence but also in indicating to you the regard I have for you and family.

Bulisa elusasheni na kuii [name is difficult to read]. Na ngomso!iii

Yours very sincerely,

Nelson

K Guzana, Esq.,

Ncambedlana,

P.O. Umtata.iv Transkei

To Mangosuthu Buthelezi,v family friend and Zulu prince

[In another hand] 466/64 Nelson Mandela

[Stamp dated and signed] Censor Office4–11–1968

My dear Chief,

I should be pleased if you would kindly convey to the Royal Family my deepest sympathy on the death of King Cyprian Bhekuzulu.vi His passing away took me completely by surprise for I did not have even the slightest hint of the King’s fatal illness. Although a few years back I had heard that his health was somewhat indifferent, a friend had later informed me that he had much improved, a fact which seemed to be confirmed by photographs that I subsequently saw in various publications and which on the face of it appeared to indicate that he was in good health. The unexpected news consequently shocked me immensely, and I have since been thinking of the Royal Family in their bereavement.

You and the late King were closely related and bound to each other by a long and fruitful friendship, and his death must have been a severe blow to you. I met him twice only; in my Johannesburg home and in my office, and on both occasions he was accompanied by you. It afforded me great pleasure to note how deeply he valued your friendship and how highly he appreciated your advice. In him we caught glimpses of the astuteness and courage that was the source of so much of the glittering achievements of his famous ancestors. In serving him as you did, you were carrying on the tradition established by my chiefs, Ngqengelele and Mnyamana, your ancestors, whose magnificent role in the task of national service is widely acknowledged.

The vast crowds that must have attended the funeral, the words of comfort delivered at the graveside and the messages of sympathy from organisations and individuals all over the country would by now have fully demonstrated that the Royal Family is not alone in mourning his unfortunate loss to the country.

The death of a human being, whatever may be his station in life, is always a sad and painful affair; that of a noted public figure brings not only grief and mourning to his family and friends, but very often entails implications of a wider nature. It may mean tampering with established attitudes and the introduction of new ones, with all the uncertainty that normally accompanies the change of personalities at the head of affairs. In due course Amazulu will no doubt be summoned to the Royal capital to deliberate over the whole situation and to make the necessary decisions. I am confident that the statesmen and elders whose vast wealth of wisdom, ability and experience have guided the fortunes of this celebrated House in the past, will, on this occasion, offer solutions which will be inspired by the conviction that the interests and welfare of all our countrymen is the first and paramount consideration. In this regard, your immense knowledge and able advice will be as crucial now as it has been in the past.

Incidentally, in December 1965 I wrote a special letter to Nkosikazi Nokhukhanyai and requested her, amongst other things, to mention me to your late cousin and to you. I indicated then that on my release I would visit Zululand to pay my respects to my traditional leader. I hope the message was received. This resolution remains unchanged, and although it will no longer be my privilege to pay homage to the late King personally, it will be an honour for me to visit Nongomai and thereafter Mahlabatini.ii

Finally, I should like you to know that I think of you and Umndlunkuluiii with warm and pleasant memories, and sincerely wish you great happiness and good health. My fond regards to Umntwana,iv your mother, and to your mother-in-law.

Yours very sincerely,

[Signed NR Mandela]

NELSON Rv MANDELA

Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi

P.O. Box 1, Mahlabatini

Zululand

To Zenani and Zindzi Mandela,vi his middle and youngest daughters

4.2.69

My Darlings,